Abstract

Objective: This descriptive study examined the quality of care received by individuals with serious mental illness observed in clinical care using established Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measures for individuals with serious mental illness.

Methods: Administrative claims (Medicaid, Medicare, and commercial) from a national health and well-being company were used to identify adults with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Performance rates for five HEDIS mental health quality measures were computed. Sub-group analyses examined each HEDIS measure by those who were medication adherent vs non-adherent, and by typical vs atypical antipsychotics.

Results: Eighty-nine percent of the Medicaid population received a diabetes screening (vs 79% for national benchmark Medicaid rates), 81% (vs 69%) received monitoring for diabetes, 88% (vs 79%) received monitoring for cardiovascular disease, 63% (vs 60%) were adherent with antipsychotic medication, and 34% (vs 61%) had a follow-up visit with a mental health practitioner within 30 days of a discharge. The rates for individuals with Medicare coverage were similar or marginally higher than those reported for those with Medicaid coverage, while rates for the commercially insured population were lower than the other groups.

Conclusions: Most (>65%) individuals with serious mental illness received the recommended screening and monitoring for diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Barriers to and reasons for lack of follow-up should be investigated to guide future interventions to improve follow-up after hospitalization for individuals with serious mental illness.

Introduction

Approximately 1% of individuals in the US are diagnosed with schizophrenia and an estimated 2.6% are diagnosed with bipolar disorderCitation1,Citation2. Individuals suffering from these conditions experience disabling psychiatric symptoms, and have a high prevalence of comorbid medical conditions such as obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and dyslipidemiaCitation3,Citation4. Monitoring physical comorbidities along with mental health treatment is needed to optimize the long-term outcomes of individuals with serious mental illnesses (SMI) such as bipolar disorder and schizophreniaCitation5–7.

The National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) monitors the quality of care at the health plan level using a set of standardized performance measures called the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS). The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act required the development of a core set of healthcare quality measures for adults using Medicaid. The goal of these measures was to help standardize healthcare quality across states and understand where improvements in care were needed. HEDIS can be used for this purpose and was utilized by 37 state Medicaid programs in 2013Citation8. More than 90% of all US health plans have used HEDISCitation9. Historically, the only measure in HEDIS that was specifically for individuals with SMI was a measure of outpatient follow-up after hospitalization for mental illnessCitation9. In 2013, new SMI measures were added: diabetes screening, diabetes monitoring, and cardiovascular monitoring for individuals with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, as well as a measure of adherence to antipsychotic medications for individuals with schizophreniaCitation9.

Individuals with SMI have a higher risk for metabolic and cardiovascular comorbidities that may be further exacerbated by treatment with some atypical antipsychoticsCitation10–12. Several of the newer atypical antipsychotics, such as olanzapine, clozapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and paliperidone, have been linked to increased risk of obesity, which in turn can increase the risks of developing other conditions, such as diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular diseaseCitation10–13. As metabolic syndrome is present in as many as 40% of individuals with schizophrenia and up to 32% of individuals with bipolar disorderCitation14–16, the HEDIS measures for diabetes screening, diabetes monitoring, and cardiovascular monitoring are particularly relevant. Weight gain and metabolic changes are of greater concern with atypical than typical antipsychoticsCitation17, therefore tracking these measures may be more important for individuals taking atypical antipsychotics.

Clinical monitoring of adherence to antipsychotic treatment is vital for outcomes, as non-adherence has been linked to greater risk of hospitalizationCitation18–20. Medication gaps of only 1–10 days in a 1-year period were associated with a two-fold increase in hospitalization riskCitation20. After hospitalization discharge, continued non-adherence to prescribed medication has been associated with “revolving door” repeat re-admissions of individuals with schizophrenia, and repeated admissions are costlyCitation21. Hospitalizations are a large percentage of direct treatment cost for schizophrenia and bipolar disorderCitation22,Citation23. Lack of adherence to medication could also reflect a more complex type of patient, such as one who lacks insight into their illness, fails to recognize psychotic symptoms, and is likely to have a broad array of poor outcomesCitation24.

The objective of this descriptive study was to examine HEDIS measures relevant to individuals with SMI enrolled in Medicaid, Medicare, or commercial plans under one larger insurer and compare them with the national HEDIS benchmarks. Unobtrusive observational data was used to assess real-world clinical practice. Given the large differences between Medicaid, Medicare, and commercial insurance in both enrollee characteristics and plan benefit design, the intent of this study was to describe HEDIS measures results from the different insurance types, not to directly compare the results between the different plan types. To better understand potential differences with antipsychotic treatment, comparisons of the HEDIS measures between individuals treated with atypical vs typical antipsychotics were examined. Potential differences between individuals who were adherent or non-adherent were also examined.

Methods

Data source

A retrospective insurance claims database study was conducted utilizing data for the calendar year 2013 from the Humana Inc limited dataset available for Comprehensive Health Insights research that was Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) compliant. Humana is a health insurance company with millions of members across the US with Medicare Advantage, stand-alone prescription drug plans, and commercial plans. Prior to initiation, the current study was reviewed and approved by Schulman Associates Institutional Review Board (IRB), a contracted independent IRB that reviews the patient health information (PHI) elements that will be used for research and to ensure protection and confidentiality of all PHI.

Selection and cohort identification

Adult individuals with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, identified through medical and pharmacy claims and based on the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modifications (ICD-9-CM), were selected. Individuals with at least one acute inpatient or at least two visits to an outpatient, intensive outpatient, partial hospitalization, emergency department (ED), or non-acute inpatient setting with a diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD-9-CM 295.x) were identified first, followed by those with bipolar disorder (ICD-9-CM 296.0-296.1 and 296.4-296.8). Individuals with diagnoses of both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder were included in the schizophrenia cohort. All individuals were required to be between the ages of 19–89 years at the index date, as certain state laws (NE, DE, AL) restrict the use of data in research for persons younger than 19 years. All claims were pulled for individuals in both cohorts from January 1 through December 31, 2013 (i.e. the measurement year).

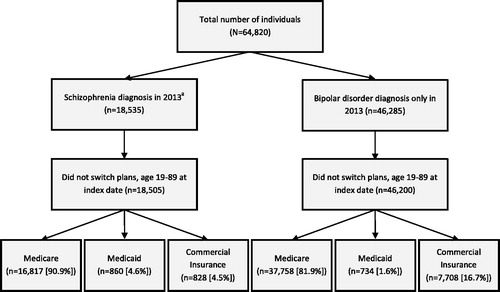

Individuals were assigned to the following groups based on type of insurance: Medicaid, Medicare (including Medicare and Medicaid dual eligible), and commercial insurance. Individuals covered by Medicaid, Medicare, or commercial insurance plans are distinct populations. Medicaid programs are administered by individual states with eligibility primarily based on income or disability status. Medicare is a national program available for those 65 years of age or older, or those who are disabled. Commercial plans generally cover employees, their spouses, or their dependents, and individuals with this plan type appear to be higher functioningCitation25. When an individual is eligible for both Medicaid and Medicare, Medicare is the primary insurance. As these populations appeared distinct, analyses were stratified by insurance type. displays the flow of individuals through the selection criteria.

Measures

HEDIS quality measures

Five mental health quality measures were examined using the definitions provided in the HEDIS technical specifications manualCitation9. The national competition rates of the Medicaid plansCitation9 were used as the benchmark value in this study. Below are brief descriptions of the eligible populations (used as the denominator) and identified populations (used as the numerator) used for each HEDIS measure performance rate calculation. Detailed criteria for each of the quality measures can be found in the .

Diabetes screening: Rate of individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder and dispensed an antipsychotic medication (denominator) who received a diabetes screening (glucose test or HbA1c test, as captured in the available lab claims data) during the measurement year (numerator).

Diabetes monitoring: Rate of individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia and diabetes (denominator) who received an LDL-C and HbA1c test during the measurement year (numerator).

Cardiovascular monitoring: Rate of individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia and cardiovascular diseases (denominator) who received an LDL-C test during the measurement year (numerator).

Medication adherence: Rate of individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia (denominator), who remained on their antipsychotic medication with a proportion of days covered of ≥80% during the measurement year (numerator).

Follow-up after hospitalization: Rate of individuals with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder with a hospital discharge (denominator) who had a follow-up visit with a mental health practitioner either within 7 days or within 30 days of discharge from index hospitalization (numerator), or not at all.

All measures followed the exact definition from the HEDIS technical specifications, with the exception of the diagnoses for the follow-up after hospitalization measures and the age range requirements. The study population was restricted to individuals with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, whereas the technical specification manual specified individuals discharged with a broad array of mental health conditions including schizophrenia, bipolar disorders, depression, psychotic disorders, pervasive developmental disorders, obsessive compulsive disorders, personality disorders, acute stress reactions, adjustment disorders, conduct disorders, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorders (ICD-9-CM: 295–299, 300.3, 300.4, 301, 308, 309, 311–314)Citation9. The age range used in the analysis was 19–89 years, as several states (NE, DE, AL) restricted patient data under the age of 19. NCQA reported data for 18–65 year olds, thus the age range used for this study does not directly overlap with those required for HEDIS.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Demographic and clinical characteristics were examined for the 12-month baseline period by type of insurance plan. The demographic characteristics included age, gender, geographical region, and race/ethnicity (for the Medicare population only). A Deyo-Charlson Comorbidity Index (DCCI) score was calculated for each individualCitation26. The DCCI is a commonly used administrative claims-based measure of overall comorbidity that weights 17 different types of comorbidities by risk of mortalityCitation27. In addition, multiple comorbidities that are relevant to the study population were flagged and tracked including alcohol/substance abuse (ICD-9-CM 291.xx, 292.0x–292.2x, 292.8x–292.9x, 303.xx–304.xx, 305.0x, 305.2x–305.9x, 965.xx, 980.0x, E950.0x–E958.0x, V65.42), anxiety/depression (ICD-9-CM 290.21, 293.84, 296.2x–296.3x, 298.0x, 300.0x, 300.11, 300.2x, 300.4x, 308.0x, 309.0x, 309.1x, 309.21, 311.xx), hyperlipidemia (ICD-9-CM 272.1–272.4), and hypertension (ICD-9-CM 401.xx-405.xx).

Performance on HEDIS quality measures

The performance rate for each of the HEDIS quality measures was calculated by dividing the number of individuals who met all the HEDIS specific criteria for each measure (identified population) by the number of individuals in the eligible population. Performance rates were calculated for each insurance type (Medicaid, Medicare, and commercially insured). The study was conducted on the population that met inclusion into the limited research data set and further restrained to individuals meeting inclusion for each HEDIS measure for this study.

Statistical analysis

This was a descriptive study. For the demographic and clinical characteristics, means and standard deviations were calculated for continuous variables, and counts and percentages were calculated for categorical variables. Rates were calculated for each of the five HEDIS quality measures using the previously described rate calculations. The rates are reported along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), which characterize the expected variation in the estimates due to chance. When the 95% CIs for two estimates do not overlap, the difference has a less than 5% chance of being due to random variation; when both confidence intervals contain both estimates then the differences are not statistically meaningfulCitation28,Citation29. All HEDIS rate calculations were computed separately for each insurance plan type (Medicaid, Medicare, and commercially insured). The HEDIS quality measure rates calculated for the Medicaid population were compared to the 2014 national rates reported by NCQA.

Sub-group analyses

Sub-group analyses were conducted to better understand two potential factors that may contribute to the overall HEDIS rates. HEDIS quality measure performance rates were recomputed for individuals who were considered adherent (proportion of days covered of ≥80% for antipsychotic medication) vs non-adherent and for individuals treated with atypical or typical antipsychotics. All analyses were completed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

The database contained 64,820 individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder in 2013. After all inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied (see ), the final sample consisted of 64,705 individuals who were between 19–89 years of age and who did not switch insurance plans. There were 18,505 individuals with schizophrenia (860 Medicaid, 16,817 Medicare, and 828 commercially insured) and 46,200 individuals with bipolar disorder (734 Medicaid, 37,758 Medicare, and 7,708 commercially insured).

shows the demographic and clinical characteristics for individuals with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder by insurance type. Those covered by Medicare were the oldest, followed by Medicaid, and then commercial insurance. For each insurance type, about half of the individuals with schizophrenia were male, while approximately one-third of the individuals with bipolar disorder were male. Mean DCCI scores were highest for Medicare, followed by the Medicaid, and then commercial insurance. Hypertension was present for half of those with Medicare, but was substantially less prevalent in the Medicaid and commercial insurance. The individuals covered by the different insurance types had large differences in demographic characteristics and rates of comorbidities, and appeared to represent distinct populations.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics for the Medicaid, Medicare and commercially-insured, schizophrenia, or bipolar populations.

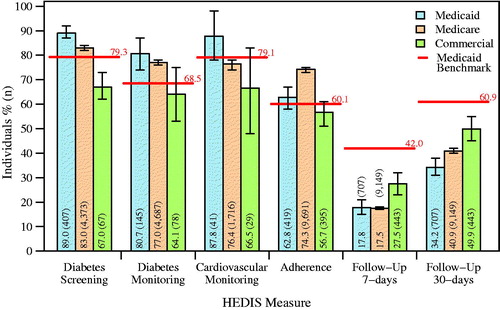

HEDIS mental health performance rates

All HEDIS mental health performance rates for each insurance type, as well as the national Medicaid rates, are displayed in . The rates for the Medicaid population were higher than the national Medicaid rates, with the exception of the follow-up care after hospitalization measures. For the Medicaid population, all of the rates were similar or slightly higher than the rates reported for the Medicare. More individuals with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder covered by Medicaid (89.0%, 95% CI = 87%-92%) received a screening for diabetes than Medicare (83.0%, 95% CI = 82–84%) or commercial insurance (67.0%, 95% CI = 62–73%). Most individuals with schizophrenia and diabetes or cardiovascular disease covered by Medicaid and Medicare received appropriate monitoring. More than half of the Medicaid and commercial insurance population with schizophrenia were considered adherent to treatment. Treatment adherence among individuals with Medicare coverage was higher than that of the other two groups. However, follow-up rates after a mental illness hospital discharge within 7-days for Medicaid (17.8%, 95% CI = 15–21%) and Medicare (17.5%, 95% CI = 17–18%) or within 30-days (Medicaid = 34.2%, 95% CI = 31–38% and Medicare = 40.9%, 95% CI = 40–42%) were much lower than the national Medicaid rates, and lower than the follow-up rates reported in the commercial population (7-days = 27.5%, 95% CI = 23–32% and 30-days = 49.9%, 95% CI = 45–55%). Within the commercially insured population, all HEDIS rates with the exception of the follow-up rates were numerically lower than the Medicaid and Medicare populations reported in the current study.

Figure 2. Performance rates for each HEDIS quality of care measure for the Medicaid, Medicare, and commercially-insured populations. The red bars and percentages represent the 2014 national rates for the Medicaid population as provided by the NCQA. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. The number of individuals used to calculate the percentage for a specific bar is given in parentheses.

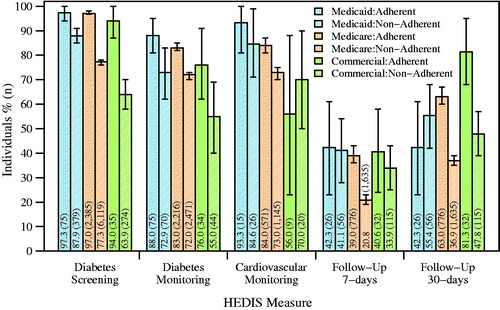

Adherence to antipsychotic medications by HEDIS mental health performance rates

Performance on the HEDIS quality measures was examined separately for individuals with schizophrenia who were adherent or non-adherent to their antipsychotic medication by insurance type (see ). Those who were adherent to their antipsychotic medications had numerically higher rates on all HEDIS quality measures across insurance type, when compared to those who were non-adherent, with two exceptions: cardiovascular disease monitoring in the commercial population (56.0% adherent vs 70.0% non-adherent) and follow-up within 30 days of hospitalization discharge in the Medicaid population (42.3% adherent vs 55.4% non-adherent). In the Medicaid population, adherence was associated with higher HEDIS performance rates for diabetes screening (adherent = 97.3%, 95% CI = 94–100% vs non-adherent = 87.9%, 95% CI = 85–91%) and diabetes monitoring (adherent = 88.0%, 95% CI = 81–95% vs non-adherent = 72.9%, 95% CI = 62–83%). Within the Medicare population, adherence was associated with higher performance rates on all HEDIS measures when compared to the non-adherent Medicare population. Adherence within the commercially insured population was associated with higher HEDIS performance rates for diabetes screening (adherent = 94.0%, 95% CI = 87–100% vs non-adherent = 63.9%, 95% CI = 58–70%) and 30-day follow-up (adherent = 81.3%, 95% CI = 68–95% vs non-adherent = 47.8%, 95% CI = 39–57%).

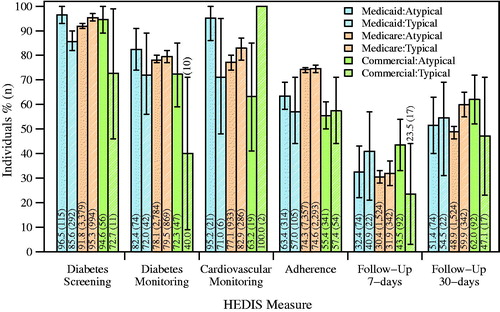

Atypical vs typical antipsychotic by HEDIS mental health performance rates

The performance levels of all HEDIS measures were also examined by type of antipsychotic medication (typical or atypical), and results were mixed across insurance type (see ). The individuals with Medicaid who were prescribed atypical antipsychotic medications showed numerically higher performance rates on all measures than the individuals with typical antipsychotics, except for lower follow-up rates. Diabetes screening was the only measure that the confidence intervals for the individuals with Medicaid coverage treated with an atypical antipsychotic did not overlap with individuals with Medicaid coverage treated with typical antipsychotic (atypical = 96.5%, 95% CI = 93–100% vs typical =85.6%, 95% CI = 82–90%). Individuals with Medicare coverage prescribed atypical antipsychotics were found to have numerically lower rates for all HEDIS measures than those treated with a typical antipsychotic. Confidence intervals of diabetes screenings for the individuals treated with an atypical and individuals treated with typical antipsychotic did not overlap (atypical = 91.8%, 95% CI = 91–93% vs typical =95.3%, 95% CI = 94–97%). Very few commercially insured individuals (n = 54) were prescribed typical antipsychotics, and the number of observations available for the cardiovascular monitoring measure (n = 2) was too small to calculate a confidence interval.

Discussion

This observational study described the performance rates on HEDIS mental health quality of care indicators for individuals with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder covered by different insurance types (Medicaid, Medicare, or commercial). While there was some meaningful variation in the rates for cardiovascular screening, diabetes screening and monitoring, and adherence by plan type, all were within 15% of the national Medicaid benchmarksCitation9. In contrast, outpatient follow-up rates after hospitalization were substantially lower than benchmark rates. Outcomes between typical and atypical antipsychotic treatment appeared similar. HEDIS measures for the adherent individuals were generally better than for the non-adherent individuals.

Populations covered by the three different insurance types in this study were distinct and not directly comparable. Individuals eligible for the national Medicare program were required to be 65 years of age or older or have a qualifying disability, and this was the dominant insurance when individuals had dual coverage. Individuals eligible for the state-run Medicaid plans were required to meet the state-by-state low-income requirements or disability requirements. Commercial plans generally covered individuals who were employed or the employee’s dependents. Commercial plans tended to have substantially higher deductibles and copayments than Medicare or Medicaid, and the out-of-pocket expenses may have influenced the decision to utilize healthcare. Although the details of the plan benefit structures likely differed between plans and were not reported in this data set, these differences may have affected the results. Therefore, it was not clear if differences between plan types were due to the distinct populations, the different benefits structures, or a combination of both.

In this current study, HEDIS diabetes screening and monitoring and cardiovascular disease monitoring were completed for the majority of individuals (64.1–89.0%). Completion of these measures is important for optimal care, as diabetes and cardiovascular disease may be exacerbated by antipsychotic medications, in particular, treatment with atypical antipsychoticsCitation30,Citation31. Although most individuals had these screenings, there was still some room for improvement. Screening for these diseases may improve outcomes, as early diagnosis and treatment of diabetes and cardiovascular disease leads to better long-term healthCitation32,Citation33. Diabetes screening and monitoring and cardiovascular monitoring were lowest in the commercial group. As this analysis was not structured to assess quality of care between the distinct insurance populations, the exact reasons for the observed differences is not known. For example, differences between patient insurance population characteristics, access to transportation, access to providers, patient cost burden, and differences in patients’ ability to understand their disease may all contribute.

Adherence to antipsychotic medications in the current study (56.7–74.3%) was similar to or higher than the Medicaid benchmark (60.1%). Comparison of adherence rates across studies is difficult, due to the high variability in adherence definitions and study methodsCitation34. Other administrative claims-based studies have reported that 43–62.5% of individuals are adherent with antipsychotic medicationsCitation19,Citation35,Citation36. Methods using the more sophisticated Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS) that electronically monitor the opening of pill bottles have also reported poor adherence with antipsychotic medicationCitation37–39. While studies using self-report or clinicians’ estimates are more commonCitation34,Citation40, they tend to over-estimate adherence, and have been found to have poor agreement with objective methods such as MEMSCitation39 or pharmacy claimsCitation36. Patient engagement across healthcare services in the insurance populations may vary, and the precise reasons underlying these adherence differences are not clear.

Interestingly, individuals in this study who were adherent to their medication were also more likely to have high-quality care on almost all the other HEDIS measures. Medication non-adherence has also been linked to poor functional outcomes such as increased risk for hospitalization, violent behavior, and housing instabilityCitation24. Medication adherence is not just a function of the efficacy and tolerability of the antipsychotic, but has been linked to many patient-related characteristics (e.g. lack of insight into illness, symptom severity, and attitude to medications) and service-related factors (e.g. therapeutic alliance, access to treatment, and follow-up planning)Citation24. Interventions such as Assertive Community Treatment appear to improve adherence and may, in turn, reduce hospitalizationsCitation41.

Rates of follow-up at 7 or 30 days for mental health outpatient visits after mental health hospitalization were significantly lower than the national rates (7 days: 17.8–27.5%, benchmark = 42%; 30 days: 34.2–49.9%, benchmark = 60.9%). However, the HEDIS benchmark follow-up rates were calculated based on multiple mental illnessesCitation9, not just schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Marcus et al.Citation42 found slightly higher rates of follow-up care at 30 days than the current study, with ∼64.0% of individuals with schizophrenia and 69.7% of individuals with bipolar disorder having outpatient mental health follow-up care. While this study did not intend to identify risk factors for the lack of follow-up care after hospitalization, prior research has reported higher rates of follow-up care among patients with outpatient mental health visits prior to hospitalization, and among patients with better antipsychotic adherenceCitation42,Citation43. After a hospitalization due to mania, many individuals with bipolar disorder do not adhere to antipsychotic treatment at discharge because of poor insight into their symptoms and the inability to recall their diagnosesCitation44. A disease management plan that included a continuity of care coordinator was effective in reducing the severity of symptoms and hospital readmissionsCitation45. Efforts to improve continuity of care after discharge may improve adherence with antipsychotic treatment, which could result in better management of illness and a reduction in hospitalizations. Strategies to improve follow-up rates at both 7 and 30-days for all individuals in the SMI population are needed.

Limitations

The studied sample included only Humana insurance plans, thus the results may not generalize to the broader US population. The age range used in this study (19–89 years) was not identical to the age range required for HEDIS measures (18–65 years), and may have contributed to differences from the national benchmarks. Similarly, the individuals were all receiving managed Medicaid or Medicare health plans, which may limit the ability to generalize results for these individuals to the broader Medicaid or Medicare populations. Administrative claims data are collected for reimbursement purposes, contain a limited amount of information, and are not as robust as clinical research data. Prescriptions filled outside of an insurance plan would not be captured. Individuals who filled prescriptions may not have taken their medication. Too few individuals with commercial insurance were prescribed typical antipsychotics to present some comparisons between those prescribed atypical and typical antipsychotics. Lastly, the individuals covered by different insurance types appear to represent distinct populations, and comparisons between the three insurance types or with the nationally reported Medicaid rates may represent differences in individual characteristics rather than differences in insurance plan administration. Future research evaluating the reasons for the differences in HEDIS measures across insurance type is needed.

Conclusions

The results suggest that, regardless of insurance type, most individuals receive care that is consistent with the HEDIS benchmarks for diabetes monitoring and screening, cardiovascular disease monitoring, and medication adherence. The HEDIS measures in this study were generally similar to the national Medicaid benchmarks, with the exception of 7 and 30-day follow-up measures. Follow-up with outpatient physicians after a hospitalization remained challenging for individuals with serious mental illness. Research examining the consequences of providing care consistent with the HEDIS measures on outcomes, at both the individual and health plan level, is warranted. Further research investigating why HEDIS benchmarks for patients with serious mental illness are not consistently met could provide guidance to improve patient care.

Transparency

Declaration of financial relationships

DNM and KR are employees of Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Acknowledgments

Technical writing support was provided by MD Stensland, PhD and GF Elphick, PhD of Agile Outcome Research, Inc. under the direction of the authors, and was funded by Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc., Marlborough, MA.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:593-602

- Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, et al. The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system. Epidemiologic catchment area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993;50:85-94

- American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder second edition. APA Pr Guidel [Internet] 2010. Available at: http://umh1946.edu.umh.es/wp-content/uploads/sites/172/2015/04/APA-Suicidal-Behaviors.pdf [Last accessed 20 April 2016]

- De Hert M, Schreurs V, Vancampfort D, et al. Metabolic syndrome in people with schizophrenia: a review. World Psychiatry 2009;8:15-22

- Keck PE, McElroy SL, Strakowski SM, et al. Compliance with maintenance treatment in bipolar disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull 1997;33:87-91

- Olfson M, Marcus SC, Doshi JA. Continuity of care after inpatient discharge of patients with schizophrenia in the Medicaid program: a retrospective longitudinal cohort analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 2010;71:831-8

- Opler LA, Caton CL, Shrout P, et al. Symptom profiles and homelessness in schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis 1994;182:174-8

- Onstad K, Khan A, Mierzejewski R, et al. Benchmarks for Medicaid adult health care quality measures: final report. Math Policy Res Natl Comm Qual Assur 2014;1-16

- NCQA. The State of Health Care Quality [Internet]. 2014. Available at: https://store.ncqa.org/index.php/catalog/product/view/id/1865

- Saha S, Chant D, McGrath J. A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia: is the differential mortality gap worsening over time? Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007;64:1123-31

- Treuer T, Hoffmann VP, Chen AK-P, et al. Factors associated with weight gain during olanzapine treatment in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder: results from a six-month prospective, multinational, observational study. World J Biol Psychiatry 2009;10:729-40

- Anderson TR, Goldberg JF, Harrow M. A review of medication side effects and treatment adherence in bipolar disorder. Prim Psychiatry 2004;11:48-54

- Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet 2013;382:951-62

- Malhotra N, Kulhara P, Chakrabarti S, et al. A prospective, longitudinal study of metabolic syndrome in patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. J Affect Disord 2013;150:653-8

- Papanastasiou E. The prevalence and mechanisms of metabolic syndrome in schizophrenia: a review. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol 2013;3:33-51

- Vancampfort D, Stubbs B, Mitchell AJ, et al. Risk of metabolic syndrome and its components in people with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry 2015;14:339-47

- Leucht S, Komossa K, Rummel-Kluge C, et al. A meta-analysis of head-to-head comparisons of second-generation antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2009;166:152-63

- Gilmer T, Dolder C, Lacro J, et al. Adherence to treatment with antipsychotic medication and health care costs among medicaid beneficieries with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:692-9

- Valenstein M, Blow FC, Copeland LA, et al. Poor antipsychotic adherence among patients with schizophrenia: medication and patient factors. Schizophr Bull 2004;30:255

- Weiden PJ, Mackell JA, McDonnell DD. Obesity as a risk factor for antipsychotic noncompliance. Schizophr Res 2004;66:51-7

- Haywood TW, Kravitz HM, Grossman LS, et al. Predicting the “revolving door” phenomenon among patients with schizophrenic, schizoaffective, and affective disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152:856-61

- Fagiolini A, Forgione R, Maccari M, et al. Prevalence, chronicity, burden and borders of bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 2013;148:161-9

- Higashi K, Medic G, Littlewood KJ, et al. Medication adherence in schizophrenia: factors influencing adherence and consequences of nonadherence, a systematic literature review. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol 2013;3:200-18

- Haddad PM, Brain C, Scott J. Nonadherence with antipsychotic medication in schizophrenia: challenges and management strategies. Patient Relat Outcome Meas 2014;5:43-62

- Archer and Marmor on Medicare versus commercial insurance - PNHP’s Official Blog [Internet]. Available at: http://pnhp.org/blog/2012/02/16/archer-and-marmor-on-medicare-versus-commercial-insurance/ [Last accessed 26 February 2018]

- Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:613-19

- Ladha KS, Zhao K, Quraishi SA, et al. The Deyo-Charlson and Elixhauser-van Walraven Comorbidity Indices as predictors of mortality in critically ill patients. BMJ Open [Internet]. 2015;5. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4563218/ [Last accessed 5 December 2017]

- Ranstam J. Why the P-value culture is bad and confidence intervals a better alternative. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2012;20:805-8

- Greenland S, Senn SJ, Rothman KJ, et al. Statistical tests, P values, confidence intervals, and power: a guide to misinterpretations. Eur J Epidemiol 2016;31:337-50

- Manschreck TC, Boshes RA. The CATIE schizophrenia trial: results, impact, controversy. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2007;15:245-58

- Bressington D, Mui J, Tse ML, et al. Cardiometabolic health, prescribed antipsychotics and health-related quality of life in people with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry [Internet] 2016;16. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5116189/ [Last accessed 30 November 2017]

- Phillips LS, Ratner RE, Buse JB, et al. We can change the natural history of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2014;37:2668-76

- Zhang P-Y. Cardiovascular disease in diabetes. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2014;18:2205-14

- Velligan DI, Lam Y-WF, Glahn DC, et al. Defining and assessing adherence to oral antipsychotics: a review of the literature. Schizophr Bull 2006;32:724-42

- Lang K, Federico V, Muser E, et al. Rates and predictors of antipsychotic non-adherence and hospitalization in Medicaid and commercially-insured patients with schizophrenia. J Med Econ 2013;16:997-1006

- Stephenson JJ, Tunceli O, Tuncelli O, et al. Adherence to oral second-generation antipsychotic medications in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: physicians’ perceptions of adherence vs. pharmacy claims. Int J Clin Pract 2012;66:565-73

- Acosta FJ, Ramallo-Fariña Y, Bosch E, et al. Antipsychotic treatment dosing profile in patients with schizophrenia evaluated with electronic monitoring (MEMS®). Schizophr Res 2013;146:196-200

- Acosta FJ, Hernández JL, Pereira J, et al. Medication adherence in schizophrenia. World J Psychiatry 2012;2:74-82

- Byerly M, Fisher R, Whatley K, et al. A comparison of electronic monitoring vs. clinician rating of antipsychotic adherence in outpatients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 2005;133:129-33

- Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, et al. Assessment of adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness: recommendations from the Expert Consensus Guidelines. J Psychiatr Pract 2010;16:34-45

- Valenstein M, McCarthy JF, Ganoczy D, et al. Assertive community treatment in veterans’ affairs settings: impact on adherence to antipsychotic medication. Psychiatr Serv Wash DC 2013;64:445-451, 451.e1

- Marcus SC, Chuang C-C, Ng-Mak DS, et al. Outpatient follow-up care and risk of hospital readmission in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Serv Wash DC 2017;68:1239-46

- Hirschfeld R. Bipolar depression: the real challenge. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2004;14:S83-8

- Makaryus AN, Friedman EA. Patients’ understanding of their treatment plans and diagnosis at discharge. Mayo Clin Proc 2005;80:991-4

- Bauer MS, McBride L, Williford WO, et al. Collaborative care for bipolar disorder: Part II. Impact on clinical outcome, function, and costs. Psychiatr Serv Wash DC 2006;57:937-45

Appendix 1: HEDIS measure definitions.