Abstract

Objective: To quantify the rate of adverse events reported with naproxen compared with placebo, ibuprofen and acetaminophen at non-prescription doses in multiple-dose, multi-day (7–10 days) duration clinical trials and further contribute towards current knowledge regarding the safety profile of naproxen.

Methods: Safety data were retrospectively collected from eight randomized, controlled trials that included subjects exposed to a fixed dosing regimen of 220–750 mg naproxen per day over 7–10 days. All data on adverse events and their duration, severity and possible relationship to the study drug were taken from the clinical study reports. The data were used in a post-hoc pooled analysis of participants exposed to naproxen 220–750 mg/day (N = 1494) and grouped according to age (<65 and ≥65 years), daily dose, race and gender.

Results: The safety profile of naproxen closely resembled that of placebo, with similar rates of adverse events across treatment groups as the active comparators. There was no dose effect of naproxen, and there were no differences in older versus younger participants. Most events were mild to moderate. The most frequently reported adverse events in all groups were related to the gastrointestinal system (most commonly dyspepsia with naproxen), with no differences between groups.

Conclusions: Our pooled analysis did not find an increased risk of adverse events with short-term use of non-prescription doses of naproxen compared with placebo, or compared to other common analgesics.

Introduction

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are one of the most commonly used drug classes worldwideCitation1, taken by an estimated 30 million people globally every dayCitation2. NSAIDs are generally available by prescription, but many are widely available without a prescription, used in around one-third of the general populationCitation3. Non-prescription NSAIDs are often taken as self-medication without the supervision of a healthcare providerCitation4. Given the availability of NSAIDs as over-the-counter drugs, there is an ongoing need to provide additional evidence regarding the risk of adverse events (AEs) associated with non-prescription NSAIDsCitation5.

Most of the common NSAIDs are nonspecific inhibitors of prostaglandin synthesis. They inhibit both the cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 enzyme that is associated with production of pain and inflammation, as well as the COX-1 enzyme that is that is constitutively expressed in most cells and is involved in processes such as protection of the stomach wall and platelet aggregation. Consequently, untoward gastrointestinal effects occur with NSAID use, especially with frequent use, higher doses and long-term useCitation6–8. Although most non-prescription use is short term and at lower dosesCitation9, the potential for an increased risk for gastrointestinal events has been reportedCitation10,Citation11. Particular care must be taken in older people. An estimated 10–40% of those aged 65 years or older use prescription or non-prescription NSAIDs every dayCitation2. Such patients are more susceptible to NSAID-associated AEs because of the physiological changes that occur with age, such as impaired drug distribution and clearance and decreased renal elimination and cardiac outputCitation12. Many also require several concomitant drugs that may further increase the risk of AEs (e.g. gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, renal, hepatic)Citation5,Citation13–15. Therefore, it is important that healthcare providers have access to all the available evidence regarding the safety of prescription and non-prescription NSAIDs.

Naproxen is regularly used to relieve pain and inflammation in various acute and chronic conditions, both at prescription and lower non-prescription doses. Several meta-analyses have indicated that naproxen has a favorable safety profile compared with placeboCitation16,Citation17, although the risk of NSAID-induced gastrointestinal AEs with naproxen has been classed as intermediateCitation14,Citation18. The purpose of our post-hoc pooled analysis was to quantify the rate of adverse events reported with non-prescription doses of naproxen compared with placebo, ibuprofen and acetaminophen, using data extracted from eight multiple-dose, multi-day (7–10 days) duration, randomized, controlled trials. As some studies have not been previously published, we believe that the safety data are important to further contribute towards current knowledge regarding the safety profile of naproxen.

Methods

Post-hoc safety analysis

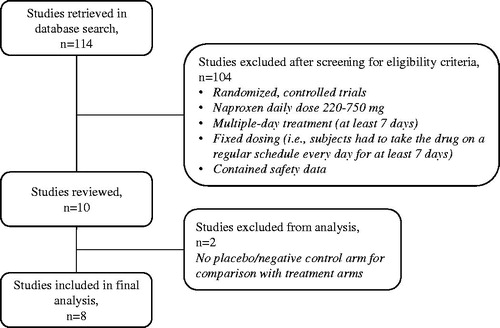

The internal company database was searched for multiple-dose, randomized controlled trials with a fixed dosing regimen for 7 days or longer that involved subjects exposed to naproxen at daily doses up to 750 mg. Eight studies were identified ( and Supplementary Table S1). Safety data from subjects exposed to up to 750 mg/day of naproxen was collected and compared to the active comparators and placebo in these studies. The incidence of adverse events by body system and preferred terms was analyzed between treatments. In one study, twelve subjects were exposed to 1100 mg/day. These subjects were not included in the analysis. However, in a secondary analysis of naproxen by daily dose, safety data for participants exposed to up to 1100 mg/day were included. All safety information was collected using the clinical study reports as the data source. The studies took place between 1992 and 2015 in Canada and the USA. Two were phase 1, open-label controlled trials in healthy volunteers, two were phase III, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled studies in acute ankle sprains, and four were phase IV, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled studies in osteoarthritis of the knee or hip. Written informed consent had been provided by each participant before treatment, and all studies were approved by the local Institutional Review Board. In the original studies, participants were ineligible for analysis if they had used an NSAID prior to the treatment period (ranging from 4 hours to 10 days). Seven trials compared naproxen with placebo, while one compared subjects taking naproxen with concomitant low-dose (81 mg) aspirin as the active group and low-dose (81 mg) aspirin alone as the negative control group. The comparators in the seven placebo-controlled trials were ibuprofen (600–1200 mg/day), acetaminophen (4000 mg/day) or low-dose aspirin (81 mg/day) (see Supplementary Table S1). The treatment duration was short term (7–10 days).

Throughout each study, AEs were recorded and evaluated according to their duration, severity and possible relationship to the study drug. This information was used in our post-hoc pooled analysis of all safety events reported in all participants. We also performed subgroup analyses according to age (<65 and ≥65 years), daily dose of naproxen, race and gender.

Statistical analysis

All AEs reported during the individual studies were mapped to preferred terms using COSTART and MedDRA. All preferred terms were mapped after data entry to system organ classes by MedDRA version 20.1, to ensure unique mapping. Multiple AEs with the same preferred terms were counted only once per patient, using the worst-case approach for severity (mild, moderate, severe) and relationship to study drug (probably not, unknown, probably).

The analysis of AEs was performed on the safety population from each study and included all participants who took at least one dose of treatment and had follow-up data. All analyses were done on an ad-hoc basis. Descriptive data are presented as number (percentage) or mean ± standard deviation, median and range, as appropriate. Pairwise comparisons were performed on the occurrence of adverse events according to system organ class by treatment, and p < .05 considered to indicate statistical significance (Fisher’s exact test). All summaries and statistical analyses were generated using SAS version 9.4 within Windows 10 environment.

Results

Participants

The participants included in the safety populations (N = 1494 overall) were either healthy volunteers (n = 138), had knee or hip osteoarthritis (n = 1234), or had acute ankle sprain (n = 122). Overall, the mean age was 55.8 (16.68) years and the majority were women (64%). The data presented in also show participants according to age <65 years (n = 950) and ≥65 years (n = 544). Subject demographics and characteristics were similar across groups, with the exception of the acetaminophen group which was slightly older on average by about 5–7 years ().

Table 1. Participant demographics and characteristics in the pooled analysis.

Naproxen safety profile

All participants

The pooled analysis showed that the safety profile of naproxen closely resembled that of placebo (). Overall, AEs were reported by 25.0% of naproxen participants, 27.6% of placebo participants, 22.0% of ibuprofen participants and 26.2% of acetaminophen participants. Gastrointestinal system AEs were most often reported (the most common with naproxen being dyspepsia, occurring in 5.0% of participants), with no significant differences between naproxen and the comparators. In fact, there were no significant differences in AEs between naproxen and placebo, ibuprofen or acetaminophen, apart from a significantly lower risk of nervous system disorders with naproxen compared with placebo (5.9% vs. 11.7%, respectively, p = .0012; ), particularly headache (3.2% vs. 7.7%, p = .0013; ). Most AEs were mild to moderate in all groups, severe events were reported by 3.8% in the naproxen group, 14.4% in the placebo group, 19.2% in the ibuprofen group and 11.7% in the acetaminophen group (). Severe AEs that were probably related to naproxen included three gastrointestinal events (abdominal pain, diarrhea, dyspepsia) and one general disorder and administration site condition (peripheral edema).

Table 2. Summary of adverse events in all participants by treatment.

Table 3. Statistically significant differences in adverse events reported with naproxen compared with placebo, ibuprofen and acetaminophen (pairwise comparison, Fisher’s exact test).

Participant subcategories

In the analysis of subjects taking naproxen by daily dose, the rates of reported AEs were similar between naproxen 440 mg/day and 660 mg/day (). Lower rates were reported in subjects taking 220 mg/day and 750 mg/day, although the sample size was smaller.

Table 4. Summary of adverse events in all participants by naproxen dose.

In participants younger and older than 65 years, there was no difference in the risk of gastrointestinal events between the age groups, and a lower reported incidence of severe AEs in each group with naproxen compared with the other treatments (). Some significant differences were noted between naproxen and the comparators in each participant subcategory (). There was a significant difference in nervous system disorders in favor of naproxen in participants <65 years compared with placebo (5% vs. 14%, respectively; p < 0.001) and ibuprofen (5% vs. 11%; p = .0074), in Caucasians compared with placebo (6% vs. 13%; p = .0002), and in females compared with placebo (6% vs. 13%; p = .0021). In all these groups, the incidence of headache was significantly lower with naproxen vs. placebo (<65 years: 2% vs. 10%, respectively, p < .0001; Caucasians: 3% vs. 8%, p = .0007; females: 4% vs. 9%, p = .0083). Although the differences only just reached significance, there was less dizziness reported with naproxen vs. ibuprofen in participants <65 years (1% vs. 4%; p = .0474) and in females (1% vs. 4%; p = .0441), and a lower rate of infection in males with naproxen vs. acetaminophen (1% vs. 6%; p = .0423). No other significant differences were noted between naproxen participants and other treatments in the subgroups, including older participants ≥65 years and healthy volunteers.

Discussion

Pooled analysis of the safety data from a relatively high number of participants included in eight multiple-dose, randomized controlled trials has indicated that the safety profile of naproxen (with dose exposure ranging from 220 to 750 mg/day over 7–10 days) was comparable to placebo. This finding is consistent with previous meta-analyses including single- and multiple-dose trials in various indications, which have also demonstrated that the rate of AEs with naproxen at non-prescription doses is similar to placeboCitation16,Citation19–21. Our analysis, unlike other analyses, focuses on studies with fixed daily dosing regimens of 7 days or longer). Participants most frequently reported one AE, with events usually mild to moderate in nature, and a lower incidence of severe complications when comparing naproxen with placebo and the other analgesics. The most common complaints with naproxen were related to the gastrointestinal system, which was also the case with placebo, ibuprofen and acetaminophen. Other studies have also found a comparable rate of gastrointestinal events with naproxen versus placeboCitation20,Citation22–24, although not all analyses are in agreementCitation25. Some analyses have found a higher rate of gastrointestinal events with naproxen and other non-selective NSAIDs, although this was compared with non-use rather than placeboCitation7,Citation26,Citation27.

In the older people (≥65 years) in our analysis, who are generally already at increased risk of complicationsCitation12,Citation13, there was no difference in the overall rate or any type of adverse event compared with younger participants. These findings are important as they contribute to the scant evidence available regarding the safety of non-prescription naproxen in older patients, many of whom regularly use non-prescription NSAIDsCitation2.

A strength of this analysis is the substantial number of participants included, with pooled data from randomized, controlled trials, although a limitation is the short duration of all studies included. Many patients are chronic users of NSAIDs and only a long-term follow-up over several months can give a true indication of the safety profile in this population. Nevertheless, our pooled analysis indicates that short-term use of non-prescription naproxen did not increase the risk of adverse events compared with placebo.

Conclusions

Short-term use of non-prescription doses of naproxen results in a similar safety profile to placebo, regardless of the age of the population. The safety data provided by this pooled analysis will help to further inform healthcare providers and consumers alike of any potential risks associated with the use of naproxen. It is advisable that patients always follow the label instructions regarding appropriate use of these products.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Bayer Consumer Health.

Author contributions: All authors were involved in the research plan, analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting of the manuscript and revising it critically for intellectual content, and final approval of the version to be published. All authors are accountable for all aspects of the work.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

All authors of this publication have disclosed that they are employees of Bayer Consumer Health. CMRO peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (19.6 KB)Acknowledgements

The draft manuscript was prepared by a medical writer, Deborah Nock (Medical WriteAway, Norwich, UK), with full review and approval from all authors and funded by Bayer Consumer Health.

References

- Holubek W, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug. In: Hoffman R, Howland M, Lewin N, et al. editors. Goldfrank’s Toxicologic Emergencies. 10th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2015.

- Conaghan P. A turbulent decade for NSAIDs: update on current concepts of classification, epidemiology, comparative efficacy, and toxicity. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:1491–1502.

- Koffeman A, Valkhoff V, Celik S, et al. High-risk use of over-the-counter non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a population-based cross-sectional study. Br J Gen Pract. 2014;64:e191–e198.

- Hamilton K, Davis C, Falk J, et al. High risk use of OTC NSAIDs and ASA in family medicine: a retrospective chart review. JRS. 2015;27:191–199.

- Moore N, Pollack C, Butkerait P. Adverse drug reactions and drug–drug interactions with over-the-counter NSAIDs. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2015;11:1061–1075.

- Lanza F, Chan F, Quigley E. Guidelines for prevention of NSAID-related ulcer complications. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:728–738.

- Castellsague J, Riera-Guardia N, Calingaert B, et al. Individual NSAIDs and upper gastrointestinal complications: a systematic review and metaanalysis of observational studies (the SOS Project). Drug Saf. 2012;35:1127–1146.

- Henry D, McGettigan P. Epidemiology overview of gastrointestinal and renal toxicity of NSAIDs. Int J Clin Pract Suppl. 2003;135:43–49.

- Duong M, Salvo F, Pariente A, et al. Usage patterns of “over-the-counter” vs. prescription-strength nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in France. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;77:887–895.

- Goldstein J, Cryer B. Gastrointestinal injury associated with NSAID use: a case study and review of risk factors and preventative strategies. Drug Healthc Patient Saf. 2015;7:31–41.

- Brune K. Persistence of NSAIDs at effect sites and rapid disappearance from side-effect compartments contributes to tolerability. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:2985–2995.

- Durrance S. Older adults and NSAIDs. Geriatr Nurs. 2003;24:6.

- Barkin RL, Beckerman M, Blum SL, et al. Should nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) be prescribed to the older adult? Drugs Aging. 2010;27:775–789.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NSAIDs – prescribing issues [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2018 Nov 6]. Available from: https://cks.nice.org.uk/nsaids-prescribing-issues

- Smith SG. Dangers of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the elderly. Can Fam Physician. 1989;35:653–654.

- Bansal V, Dex T, Proskin H, et al. A look at the safety profile of over-the-counter naproxen sodium: a meta-analysis. J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;41:127–138.

- Derry C, Derry S, Moore R, et al. Single dose oral naproxen and naproxen sodium for acute postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2009:CD004234.

- Henry D, Lim L, Garcia Rodriguez L, et al. Variability in risk of gastrointestinal complications with individual non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: results of a collaborative meta-analysis. BMJ. 1996;312:1563–1566.

- Thorlund K, Toor K, Wu P, et al. Comparative tolerability of treatments for acute migraine: a network meta-analysis. Cephalalgia. 2017;37:965–978.

- DeArmond B, Francisco C, Lin J, et al. Safety profile of over-the-counter naproxen sodium. Clin Ther. 1995;17:587–601.

- Mason L, Edwards J, Moore R, et al. Single dose oral naproxen and naproxen sodium for acute postoperative pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;4:CD004234.

- Schiff M, Minic M. Comparison of the analgesic efficacy and safety of nonprescription doses of naproxen sodium and ibuprofen in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. J Rheumatol. 2004;3:1373–1383.

- Golden H, Moskowitz R, Minic M. Analgesic efficacy and safety of nonprescription doses of naproxen sodium compared with acetaminophen in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Am J Ther. 2004;11:85–94.

- Fricke JR, Halladay SC, Francisco CA. Efficacy and safety of naproxen sodium and ibuprofen for pain relief after oral surgery. Curr Ther Res. 1993;54:619–627.

- Coxib and traditional NSAID Trialists’(CNT) Collaboration, Bahal AN, Emberson J, et al. Vascular and upper gastrointestinal effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: meta-analyses of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2013;382(9894):769–779.

- Peterson K, McDonagh M, Thakurta S, et al. Drug class review: nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): final update 4 report. Portland (OR): Oregon Health & Science University; 2010.

- Massó González E, Patrignani P, Tacconelli S, et al. Variability among nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;62:1592–1601.