Abstract

Objective: Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is a prevalent health problem. Oral agents, with the exception of metformin, are often discontinued with the initiation of insulin. The objective was to understand the proportion of patients discontinuing dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP-4is) and the reasons for the decision to discontinue.

Methods: A retrospective study using a health claims database investigated discontinuation of DPP-4i in adult patients on a dual therapy of metformin and DPP-4i who initiated insulin (n = 3391). An online survey administered to 406 physicians in the US examined reasons for discontinuation. Physicians surveyed included endocrinologists (34.5%), general practitioners (32.5%), internal medicine specialists (30.5%), and diabetologists (2.5%), treating a monthly average of 154 patients.

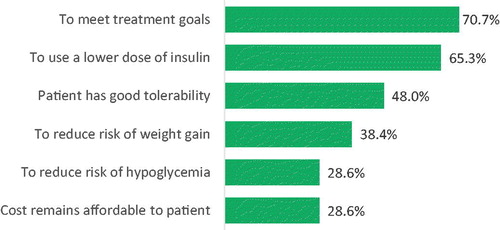

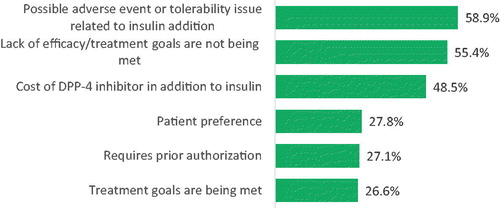

Results: Among patients treated with metformin and DPP-4is who were newly prescribed insulin, 33.3 and 57.3% discontinued DPP-4i therapy within 3 and 12 months, respectively. Patients who discontinued DPP-4i therapy had higher out-of-pocket costs and a greater proportion of renal and liver disease. Top 3 responses for discontinuation included adverse events/tolerability issues (58.9%), lack of efficacy/treatment goals not being met (55.4%) and additional cost of DPP-4i with insulin (48.5%). Top 3 responses for continuing DPP-4i included meeting treatment goals (70.7%), using a lower dose of insulin (65.3%) and good tolerability (48.0%). Physician characteristics, such as physician specialty, age, gender and location impacted to some extent the reasons for treatment decisions.

Conclusions: A large proportion of patients discontinue DPP-4is in the real world when initiating insulin. The impact of physician characteristics in treatment decisions highlights the need for enhanced physician training and support as new clinical data emerges and therapy options are available.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a common health problem with an increasing prevalence. As of 2017, it is estimated that about 425 million people (age group: 20–79 years) had diabetes worldwide. The estimated global prevalence of 8.8% is expected to rise to 9.9% by 2045Citation1. In the US alone, 9.4% (30.3 million) of the population had diabetes in 2015 and 84.1 million people had prediabetes, which often leads to type 2 diabetes (T2D)Citation2. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D) is reported to be the most common type of diabetes, accounting for around 90% of the casesCitation2. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) recommend metformin, an oral antidiabetes drug (OAD), as the first-line treatment for T2DCitation3. If HbA1c levels fail to achieve the target while treated with metformin, addition of other treatments, such as sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP-4is), sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT-2is), glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1ras) or basal insulin, should be considered sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT-2is)Citation4. When levels of HbA1c fail to decrease to the desired target, the current guidelines recommend addition of basal insulin to the regimen. In the case of DDP-4i, continuation of this therapy after insulin initiation has been shown to have advantages. Recent randomized clinical trials demonstrated that among patients initiating insulin therapy, continuing DPP-4i, sitagliptin, resulted in a clinically meaningful greater reduction in HbA1c without an increase in hypoglycemia compared to sitagliptin discontinuationCitation5,Citation6. Nevertheless, discontinuation of oral drugs such as DPP-4i upon insulin initiation is common and characteristics associated with this discontinuation are not well understood.

The objectives of this study were, therefore, to better understand the proportion of patients who discontinued DPP4-is following the initiation of insulin in the US and to assess the physicians’ reasons for discontinuation of DPP-4is when initiating insulin among patients with T2D in the US.

Methods

Study design and data source

Retrospective cohort study using the US claims database

A retrospective cohort study was conducted using the Clinformatics Data Mart (CDM). The CDM (formerly called InVision Data Mart or “LabRx”) is a database comprised of administrative health claims for members of a large national managed care company affiliated with Optum. These administrative claims are submitted for payment by providers and pharmacies and are verified, adjudicated, adjusted, and de-identified prior to inclusion in CDM. Data are included for only those covered lives with both medical and prescription drug coverage, to enable users to evaluate the claims related to the complete health care experience. Additionally, the CDM includes results for outpatient lab tests processed by large national lab vendors under contract with the managed care organization and is comprised of commercial health plan data and Medicare Advantage members. The population is geographically diverse, spanning all 50 statesCitation7. Adult patients (>18 years) diagnosed with T2D, on a dual therapy of metformin and DPP-4i and who initiated insulin (index date) from January 2006 to September 2015 with no previous history of insulin claims in the previous 6 months from the index date [pre-index period] and maintaining insulin for the 1-year were included. Data on discontinuation of DPP-4i were collected. Discontinuation was defined using the pharmacy fill date and days supply of DPP-4i and an accompanying grace period of 90 days. The date of discontinuation for the DPP-4i was defined as the date of the end of days of drug supply indicated by the date of prior prescription + gap of 90 days. A switch from one drug to another within the class was not be considered discontinuation. The follow-up period for these T2D patients’ claims was 12 months + 90 days.

The following patient variables were retrieved from CDM: age, gender (male, female), geographic area of residence (Northeast, Midwest, West, South), physician specialty (IM, Endocrinology & Metabolism, Cardiovascular Dis/Cardiology, Family Practice, Other, Missing), Charlson Comorbidities Index (CCI) score, Diabetes Complications Severity Index (DCSI), pre-index healthcare utilization (number of physician visits, number of emergency room visits, number of hospitalizations, total days of hospitalization, nursing home resident), and out of pocket cost in US dollars per person (USD PP) was calculated for cost of insulin, cost of oral anti-hyperglycemic agents (metformin and DPP-4i) and total drug cost. Out of pocket costs were calculated for the index date, defined as the date of the first basal insulin prescription (initiation) in the database. This was taken from the pharmacy claims table in Optum, which includes deductible and copayment only.

Cross-sectional web-based physician survey

A separate cross-sectional, internet-based survey was conducted from November 2018 to January 2019 to examine physician reasons for discontinuation of DPP-4i in the US and included primary care physicians (PCPs), internal medicine physicians and specialists (endocrinologists and diabetologists) with 3–45 years of practice, who were invited via an opt‐in online web panel. The M3 Global Research panel is an actively managed double opt‐in online panel, for which physicians firstly opt‐in via an initial recruitment form and are then sent an automated email to confirm that they want to join the panel. Upon agreement to join the panel, M3 Global Research has a stringent verification process in order to confirm a respondent’s practicing status. In the US, 100% of panelists are verified using the American Medical Association database. Once identified, physicians were contacted via email or telephone and screened against the inclusion/exclusion criteria, and then provided an email and link to an online internet‐based survey. A sample of 16,677 physicians was invited to the study. From those, 23% (n = 3438) assessed the survey and 406, who met all inclusion criteria, completed it. Most of the physicians that did not complete either quit during the screening (n = 1274), or were terminated (n = 1313) mostly because they did not see the minimum number of diabetes patients in a month (n = 514).

All participants gave written informed consent before study procedures started. The study was reviewed and granted exemption status by the Pearl Institutional Review Board (Indianapolis, IN; 18-KABT-179). The survey included 406 physicians from a pre-existing physician panel, among which (i) 34.5% were endocrinologists; 32.5% were general practitioners (GPs); 30.5% were internal medicine (IMs) and 2.5% were diabetologists; (ii) at least 60% of their professional time is spent on direct patient care; (iii) at least 50% of their professional time spent in a private, community, or academic practice, (iv) at least 40 T2D patients (or 60 for endocrinologists) are personally managed per month; (v) at least 1 patient naïve to insulin was treated with DPP-4i in the 3 months prior to long-acting insulin initiation and DPP-4i was continued for at least 3 months after insulin initiation; and (vi) at least 1 patient naïve to insulin was treated with DPP-4i in the 3 months prior to long-acting insulin initiation and DPP-4i was discontinued within 3 months of insulin initiation. Variables included in the physician survey were age, gender (male, female), geographic area of residence (Northeast, Midwest, West, South), specialty (GP, IM, Endocrinology, Diabetology), practice type (HMO, integrated delivery system, neither), type of hospital (academic, community), treated population (major metropolitan area, urban/suburban area, small city, rural or small town), years of practice, proportion of time spent in academic/community settings. The survey also included reasons for the continuation and discontinuation of DPP-4i ().

Table 1. Reasons for continuation and discontinuation within 3 months of the DPP-4i + insulin after initiating insulin included in the web-survey.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted on all study variables. Mean, median, minimum, maximum, and standard deviations were recorded for continuous or discrete variables whereas frequencies and percentages were considered for categorical variables. Additionally, bivariate analysis was used to investigate the relationship between physician characteristics and reasons for the continuation and discontinuation of DPP-4i. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and independent samples t-tests were performed for continuous/discrete variables to assess the difference between groups. For categorical variables, chi-square and binomial proportion tests were used to assess differences between the groups.

Results

Timing of the discontinuation of DPP-4i following insulin initiation

A total of 3391 patients were identified in the claims database as meeting the inclusion criteria. Of patients treated with metformin and DPP-4i and newly prescribed insulin, 33.3% (n = 1128) and 57.3% (n = 1942) discontinued DPP-4i therapy at 3 and 12 months, respectively (). Analyses conducted during two separate time periods (2006–2010 and 2011–2015) investigated the hypothesis that discontinuation rates differed across time and showed similar DPP-4i discontinuation rates upon insulin initiation, For example, discontinuation rates within 1 month from insulin initiation was 21.1% and 19.3% for each time period, respectively.

Table 2. Discontinuation of DPP-4i in T2D patients on dual therapy of metformin + DPP-4i at index date (insulin initiation) for each cohort (claims).

Characterization of patients with T2D who continue or discontinue DPP-4i following insulin initiation

The average age of patients who discontinued DPP-4i was significantly lower than those who were continued DPP-4i following insulin initiation (58.0 ± 12.888 vs. 59.2 ± 11.3, p = .02). A higher proportion of discontinued patients were Medicare members (34.0% vs. 30.5%, p = .03). Patients who discontinued DPP-4i were more likely to have concomitant conditions like chronic renal disease (8.7% vs. 5.5%, p < .01) and liver disease (8.9% vs. 6.8%, p = .03) than those who were continued on therapy; whereas patients who continued DPP-4is were more likely to suffer from hypertension (82.2% vs. 77.3% p < .01) than those who discontinued DPP-4is. Higher pre-index healthcare resource utilization, with more frequent physician visits (p = .02), a higher number of hospitalizations (p < .01), and a longer length of stay (p < .01) were observed for patients who discontinued DPP-4i. Out-of-pocket costs at index date were also significantly higher for those patients who were discontinued the DPP-4i therapy compared to those who continued use (p < .01) (). The study did not analyze the early vs. later discontinuers as the groups were very small and key information such as HbA1c and body mass index (BMI) was missing. This study also did not look at the number of distinct medications that a patient was on at index.

Table 3. Baseline characteristics of DPP-4i users at the time of insulin initiation.

Physician characteristics included in the survey

Physicians treated an average of 154 ± 101 patients per month. The majority of physicians were male (74.6%) and more than half were under 55-years-old (68.7%). Most physicians were practicing in a community setting (93.1%), in major metropolitan or urban areas (82.3%) ().

Table 4. Detailed physician characteristics.

Reasons for continuation

All physicians were asked to indicate the most important reasons that would lead them to continue PP-4i therapy after initiating treatment with insulin. The top three reasons noted by physicians for the continuation of DPP-4i were meeting treatment goals (70.7%), using a lower dose of insulin (65.3%), and good tolerability (48.0%). Other reasons frequently mentioned included reduced risk of weight gain (38.4%), reduced risk of hypoglycemia (28.6%), and affordable cost (28.6%) ().

Reasons for discontinuation

The top three reasons reported by physicians for discontinuation of DPP-4i within the first 3 months after insulin initiation included possible adverse events or tolerability issues related to adding insulin (58.9%), lack of efficacy/treatment goals not being met (55.4%) and cost of DPP-4i in addition to insulin (48.5%). Other frequently mentioned reasons included patient preference (27.8%), prior authorization requirements (27.1%), and treatment goals being met (26.6%) ().

Physician characteristics across the top reasons for continuation

The survey showed that there was general agreement among physicians for most reasons to continue DPP-4i beyond the first 3 months following insulin initiation, with the most cited reason being meeting treatment goals. However, differences were observed for characteristics such as age, gender, and location of the treated population. For example, older physicians (55.9%) were more likely than younger physicians (44.4%) to list patients having good tolerability as a top reason for continuation (p = .03). Female compared to male physicians were more likely to cite meeting treatment goals as a reason for continuation (78.6 vs. 68.0%, respectively, p = .04). The location of the treated patient population was a predictor for physicians with noting tolerability as a top reason for continuation. Specifically, good tolerability was listed by 65.6% of physicians in rural or small towns compared to 32.5% from small cities, 51.3% from urban/suburban areas, and 43.7% from major metropolitan areas (p = .03). ().

Table 5. Physician characteristics across the top reasons for continuation (n = 406).

Physician characteristics across the top reasons for discontinuation

Differences in physician characteristics for reasons for discontinuation of DPP-4i within the 3 months following insulin initiation were observed by physician type, age, gender, years in practice, and proportion of time practicing in an academic compared to a community setting. Physician reasoning differed between GPs, IMs, and endocrinologists for almost all reasons. For example, unmet treatment goals were reported by 34.9% of GPs, 29.0% of IMs, and 17.9% of endocrinologist (46.4%) enumerated possible adverse event or tolerability issues as a reason for discontinuation (p < .1). On the other hand, a higher proportion of endocrinologists (63.6%) reported lack of efficacy or unmet treatment goals as reasons for discontinuation, as compared to GPs (50.8%) and IMs (50.5%) (p = .04). GPs were more likely to report the pre-authorization requirements (34.9%, p = .02) and treatment goals being met (34.9%, p < .01) as reasons for discontinuation.

Older physicians (33.9%) were more likely than younger physicians (23.3%) to list the treatment goals being met as a reason for discontinuation (p = .03). A higher proportion of female physicians reported lack of efficacy/treatment goals not being met as a reason for discontinuation (69.9 vs. 55.1%; p = .01). The mean years of practice for physicians reporting cost of DPP-4i and treatment goals being met as one of the top reasons for discontinuation was higher than the average number of years of practice of the whole sample of physicians (p = .01). Physicians in community settings (28.3%) were more likely to report prior authorization requirements as a reason for discontinuation (p = .04) than the physicians in academic settings (10.7%). No differences were observed across practice type, treated populations or geographic regions ().

Table 6. Physician characteristics across the top reasons for discontinuation (n = 406).

Discussion

This study evaluated real-world treatment patterns with DPP-4is in the US, including the large proportion of patients who discontinued DPP-4i when initiating insulin and reasons for discontinuation and continuation of DPP4-is when initiating insulin. This study showed that 66.7% of patients treated with metformin and DPP-4i continued treatment 90 days after insulin initiation after applying the discontinuation rule of end of drug supply + 90-day gap. Xu et al.Citation8 using Truven Health Analytics’ Marketscan Commercial Claims and Encounters database for 2010–2015 reported that 70.7% of DPP-4i combination therapy users and 77.7% of DPP-4i monotherapy users continued treatment 90 days after the initiation of insulin therapy. The authors defined continuation of therapy as drug refill prescription 90 days after insulin initiationCitation8 which assumes a 90-day drug supply. This could have led to the overestimation in continuation of DPP4-is combination therapy by Xu et al.Citation8 or the underestimation in our study due to the more conservative definition of discontinuation.

To our knowledge, there is no other study available investigating why physicians decide to discontinue DPP-4is upon insulin initiation despite the potential clinical advantages associated with the continuation of therapy. A substantial proportion of physicians citing possible tolerability or AEs related to the addition of insulin underscored the importance of achieving good clinical outcomes. Notably, potential fear of AEs is an important limiting factor, as shown by the physicians’ response. This fear could be most likely related to the addition of insulin. As monotherapy, DPP-4is do not cause hypoglycemia because of the glucose-dependent mechanism of action. In a study of patients with T2D and inadequate control on insulin (with or without metformin) in which a DPP-4i was added and insulin therapy was intensified, a lower event rate (1.7 vs. 3.6 events/participant-year) and incidence of symptomatic hypoglycemia (25.2 vs. 36.8%; p = .001) was observed for DPP-4i compared with placeboCitation9,Citation10. In another randomized control trial, continuation of a DPP-4i when initiating basal insulin was shown to be associated with better glycemic control (mean HbA1c and least squares (LS) mean change from baseline in HbA1c were 6.85% and −1.88% in the treatment group and 7.31 and −1.42 in the placebo group), a lower daily insulin dose (53 vs. 61 units), and no difference in the incidence of hypoglycemia after 30 weeksCitation5. In a study of patients with T2D and in which a DPP-4i was added therapy was intensified for DPP-4i compared with placebo. In another randomized control trial, continuation of a DPP-4i when initiating basal insulin was shown to be associated with better glycemic control (mean HbA1c and least squares (LS) mean change from baseline in HbA1c were 6.85 and −1.88% in the treatment group and 7.31 and −1.42% in the placebo group), a lower daily insulin dose (53 vs. 61 units), and no difference in the incidence of hypoglycemia after 30 weeksCitation5. The cost of DPP-4i in addition to insulin was also reported as a potential reason for discontinuation which would be less of an issue outside the US where, for example in the UK, patients do not contribute to the costs of their anti-diabetes medication.

The most important reason for the continuation of DPP-4i reported by physicians was “to meet treatment goals”, followed by “to use a lower dose of insulin”. DPP-4is are known to significantly improve beta-cell function both when administered as a monotherapy or as part of a more complex regimen, and several studies also suggest that DPP-4i improves sensitivity to insulinCitation11–15. Basal insulin administration aims at reducing fasting and pre-meal glycemic values in T2D patients. However, the progressive diminution of insulin secretory capacity often leads to poor post-prandial and overall glycemic control. Due to the stabilization of endogenous GLP-1 and GIP by DPP-4is, post-prandial glycemic control might be improved. This is particularly important as risk of recurrent biochemical hypoglycemia increases as basal insulin is progressively titrated to achieve desired HbA1c targetsCitation16–19. Thus, continuation of DPP-4i after initiating insulin has considerable advantages. In addition, incretin-based DPP-4i therapy in combination with insulin has weight-sparing effect and low propensity to elicit hypoglycemiaCitation20,Citation21.

Few differences were observed for most of the reasons for continuation. Female physicians compared to male physicians, were more likely to report meeting treatment goals as the top reason for continuation. Physicians aged 55 years and older were more likely to list patients having good tolerability as a top reason for continuation than those who were <55 years old. This trend could be attributed to the uncertainties about the AEs, toxicity, tolerance, and lack of risk-benefit data on the treatment, especially among the younger physicians. Physicians in rural or small towns were more likely to report “good tolerability” as a top reason for continuation. A study in Germany reported that physicians living and practicing in rural and small towns had closer and longer-term relationships with their patients than those in urban areas. Also, patients in rural areas seemed to have greater trust in the expertise and competency of their doctorsCitation22. One could therefore hypothesize that the reason behind physicians in rural or small towns being more likely to report “good tolerability” as a top reason for continuation can be due to the fact that a more personal relationship with their patients would lead physicians to have a greater concern regarding the well-being and quality of life of their patients and, therefore, treatment tolerability issues.

Several physicians and practice characteristics were associated with the reasons to discontinue DPP4-is within 3 months following insulin initiation. It was observed that endocrinologists were more likely to list a possible adverse event or tolerability issues as a reason for discontinuation when compared to GPs and IMs. A higher proportion of female physicians reported lack of efficacy/treatment goals not being met as a reason for discontinuation. Few studies have examined gender differences in the practice of medicine; however, existing literature suggests that women physicians may conduct longer visits and ask more questions than male physiciansCitation23. It was also found that physicians with more years of practice were most likely to list cost of DPP-4is and treatment goals being met as reasons for discontinuation. This could be due to physicians’ anchoring based on the state of diabetes care guidelines and evidence during their training period. Physicians in community settings were twice more likely than those in academic settings to report prior authorization requirements as a reason for discontinuation, which could be specific to the current sample of physicians. In addition, older physicians were more likely than younger physicians to list the treatment goals being met as a reason for discontinuation. The reason could be the familiarity and awareness about the individualized HbA1C goals in patients with T2D among older physicians. In a recent study, physicians widely used the concept of individualizing glycemic goalsCitation24.

The major limitations of the database study include the lack of information on HbA1c and other clinical variables such as BMI, as well as data on regime change and/or use of alternative agents. In this study, although half of the patients discontinued DPP-4is within the first year after starting insulin, data available from medical/pharmacy claims did not identify factors strongly predictive of discontinuation. This led to the need to conduct a primary data collection study that specifically asked physicians why they would discontinue DPP-4is in their patients initiating insulin to better understand the reasons for this treatment change. The possible limitations of the physician survey study include reporting errors and missing information on these variables of interest as study variables are based on self-report by the physicians and are not corroborated by verifying patient charts or visits to the clinic. However, systematic bias on the part of the physician is not expected. A sampling bias could result from the inclusion criteria that physicians must be able to provide the two types of charts (i.e. continuers and discontinuers of DPP-4i). This could potentially result in the over/under-representation of physicians, if any, who always discontinue or always continue treatment with DPP-4i. As is inherent with any research relying on convenience sampling methods, it is possible that certain subgroups of physicians, such as small vs. large clinics, maybe over/under-represented and that results may not generalize to the entire physician population. Academic physicians might be under-represented, which could have led to the possible reason for the pre-authorization being listed as a top reason for discontinuation. In both the database study and the survey study, we did not identify the patient reasons for discontinuation of DPP-4is after insulin initiation. In addition, the number of other medications that a patient might be on was not explored in this study.

Conclusions

In conclusion, a large proportion of patients discontinue DPP-4is in the real world in the US. The physician survey highlights the major reasons for this treatment decision. Physician characteristics, such as physician specialty, age, gender, and location, were found to impact to some extent the reasons for the treatment decisions highlighting the need for enhanced physician training and support as new clinical data emerges and therapy options are available.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Funding for this research was provided by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA, which approved the study concept and reviewed and approved the submitted manuscript.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

GF, LY, IG, and SR are all employees of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA. KI was an employee of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA at the time of the analysis. JEM and DHJ are employees of Kantar, Health Division. GB was an employee of Kantar, Health Division at the time the research study was conducted, Kantar was provided funding from Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp for conducting the study, study design, data collection, analyses and manuscript preparation. A peer reviewer on this manuscript has disclosed consulting and receiving research funding from several companies manufacturing glucose lowering agents. The peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Author contributions

GF, LY, KI, IG, JEM, DHJ, and SR contributed to the study design, protocol, data analysis and writing of the manuscript. GB contributed to the study design and study conduct. All authors contributed to revising the paper critically for intellectual content. All authors approved the final version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Previous presentations

A portion of the results in this manuscript were presented as a research poster at the 79th Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Amit Koushik, MS of Indegene Pvt Ltd for assistance with the literature review and editing assistance of the manuscript. Funding for this assistance was provided by Kantar, Health Division.

References

- International Diabetes Federation [Internet]. IDF Diabetes Atlas. 9th ed. Brussels, Belgium; 2019. Available from: http://www.diabetesatlas.org.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Internet]. National diabetes statistics report: estimates of diabetes and its burden in the United States; 2017 [cited 2019 May]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics/statistics-report.html.

- Patrick AR, Fischer MA, Choudhry NK, et al. Trends in insulin initiation and treatment intensification among patients with type 2 diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(2):320–327.

- Davies MJ, D’Alessio DA, Fradkin J, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2018. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Dia Care. 2018;41(12):2669–2701.

- Roussel R, Duran‐García S, Zhang Y, et al. Double‐blind, randomized clinical trial comparing the efficacy and safety of continuing or discontinuing the dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inhibitor sitagliptin when initiating insulin glargine therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes: the CompoSIT‐I Study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;21:781–790.

- Linjawi S, Sothiratnam R, Sari R, et al. The study of once- and twice-daily biphasic insulin aspart 30 (BIAsp 30) with sitagliptin, and twice-daily BIAsp 30 without sitagliptin, in patients with type 2 diabetes uncontrolled on sitagliptin and metformin—The Sit2Mix trial. Primary Care Diabetes. 2015;9(5):370–376.

- Optum, Inc. Optum® Clinformatics® for Market Intelligence, version 7.2 [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Jul 7]. Eden Prairie, MN: Optum, Inc. Available from: https://www.optum.com/solutions/life-sciences/explore-data/advanced-analytics/market-intelligence.html.

- Xu Y, Pilla SJ, Alexander GC, et al. Use of non-insulin diabetes medicines after insulin initiation: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2019;14(2):e0211820.

- Mathieu C, Shankar RR, Lorber D, et al. A randomized clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of co-administration of sitagliptin with intensively titrated insulin glargine. Diabetes Ther. 2015;6(2):127–142.

- Engel S, Wu F, Xu L, et al. Reduced incidence of hypoglycaemia with sitagliptin used with intensively titrated insulin may be due to factors other than the difference in insulin dose [Internet]. Stockholm (Sweden): EASD; 2015 [cited 2019 July 7]. Available from: https://www.easd.org/virtualmeeting/home.html#!resources/reduced-incidence-of-hypoglycaemia-with-sitagliptin-used-with-intensively-titrated-insulin-may-be-due-to-factors-other-than-the-difference-in-insulin-dose–2.

- Xiang AH, Peters RK, Kjos SL, et al. Effect of pioglitazone on pancreatic-cell function and diabetes risk in Hispanic women with prior gestational diabetes. Diabetes. 2006;55(2):517–522.

- Ahren B. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors: clinical data and clinical implications. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(6):1344–1350.

- Ahren B, Pacini G, Foley JE, et al. Improved meal-related -cell function and insulin sensitivity by the dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibitor vildagliptin in metformin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes over 1 year. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(8):1936–1940.

- Lyu X, Zhu X, Zhao B, et al. Effects of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors on beta-cell function and insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):44865.

- Jensterle M, Goricar K, Janez A. Add on DPP-4 inhibitor alogliptin alone or in combination with pioglitazone improved β-cell function and insulin sensitivity in metformin treated PCOS. Endocr Res. 2017;42(4):261–268.

- Pontiroli AE, Miele L, Morabito A. Metabolic control and risk of hypoglycaemia during the first year of intensive insulin treatment in type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes, Obes Metabol. 2012;14(5):433–446.

- Little S, Shaw J, Home P. Hypoglycemia rates with basal insulin analogs. Diabetes Technol Therap. 2011;13:S-53–S-64.

- Rosenstock J, Fonseca V, Schinzel S, et al. Reduced risk of hypoglycemia with once-daily glargine versus twice-daily NPH and number needed to harm with NPH to demonstrate the risk of one additional hypoglycemic event in type 2 diabetes: evidence from a long-term controlled trial. J Diabetes Complications. 2014;28(5):742–749.

- Owens DR, Traylor L, Mullins P, et al. Patient-level meta-analysis of efficacy and hypoglycaemia in people with type 2 diabetes initiating insulin glargine 100U/mL or neutral protamine Hagedorn insulin analysed according to concomitant oral antidiabetes therapy. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;124:57–65.

- Foley JE, Jordan J. Weight neutrality with the DPP-4 inhibitor, vildagliptin: mechanistic basis and clinical experience. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2010;6:541–548.

- Dejager S, Schweizer A. Minimizing the risk of hypoglycemia with vildagliptin: clinical experience, mechanistic basis, and importance in type 2 diabetes management. Diabetes Ther. 2011;2(2):51–66.

- Pohontsch NJ, Hansen H, Schäfer I, et al. General practitioners’ perception of being a doctor in urban vs. rural regions in Germany - A focus group study. Family Pract. 2018;35(2):209–215.

- Hall JA, Irish JT, Roter DL, et al. Gender in medical encounters: an analysis of physician and patient communication in a primary care setting. Health Psychol. 1994;13(5):384–392.

- Genere N, Sargis RM, Masi CM, et al. Physician perspectives on de-intensifying diabetes medications. Medicine. 2016;95(46):e5388.