Abstract

Objective: To evaluate the effect of individual lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and LUTS-specific bother on daily/leisure activities, work productivity and treatment behaviors and satisfaction in a Brazilian population reporting symptoms of the overactive bladder (OAB) syndrome.

Methods: Secondary analysis of Brazil LUTS study data, including individuals ≥40 years old with a possible diagnosis of OAB, based on a score of ≥8 on the OAB-V8 questionnaire. Participants used a 5-point Likert scale to rate occurrence of LUTS during the previous month. Regression models were constructed to analyze association of symptom frequency and bother, controlled for demographics, comorbid conditions, habits and body mass index, to outcomes related to people’s lives and treatment patterns.

Results: This analysis included 5184 individuals (53% female), 24.4% of whom received a possible diagnosis of OAB. There was a greater likelihood of OAB symptoms in men reporting depression/anxiety (2.0 times), diabetes (1.8 times), or constipation (1.9 times) and women reporting depression/anxiety (2.6 times), constipation (1.7 times), and being overweight (1.4 times) or obese (1.8 times). Symptoms of all categories, including voiding, storage, and post-micturition, were associated with a negative impact on individuals’ lives, quality of life and treatment-related outcomes. Treatment seeking for OAB was low among men and women overall (35.1 and 43.6%, respectively), with highest rates among individuals in the 60–69 age group.

Conclusions: LUTS of all categories impacted all domains studied. These results highlight the importance of comprehensive LUTS assessment in OAB patients, including voiding, storage and post-micturition symptoms.

Introduction

Overactive bladder (OAB) has a negative impact on the daily activities of affected individuals. It has the potential to impair multiple domains of quality of life (QoL)Citation1,Citation2, including restriction of social and work lifeCitation3,Citation4, while also resulting in higher healthcare resource use and costsCitation5. Despite the impact of OAB on QoL, treatment-seeking behavior is considered low.

OAB affects an estimated 12–17% of adults and has a similar reported prevalence in men and womenCitation4,Citation6 however, depending on how OAB is defined, higher prevalence rates have been reported. In the Epidemiology of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (EpiLUTS) cross-sectional internet-based survey of adults aged ≥40 years, the overall prevalence of OAB among respondents in the United States ranged from 11 to 23% depending on the frequency of symptoms and the extent of bother. The EpiLUTS used current International Continence Society (ICS) definitions, in which OAB was defined as the presence of urinary urgency or urgency urinary incontinence (UUI)Citation7.

Studies of patients with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) have focused mainly on individuals of European ancestry living in high-income countries. Between-country differences in work culture may influence how OAB impacts men and women in the workplace, highlighting the need for further research in countries not investigated in previous population-based studies. Some published data suggest that Hispanic people have a higher risk of moderate or severe LUTS compared with CaucasiansCitation8. The few published studies of Latin American populations have provided epidemiological data, while overlooking the impact of OAB on work, QoL, and treatment-seeking behaviorCitation9–14. The Colombian Overactive Bladder and Lower urinary Tract symptoms (COBaLT) study of 1060 individuals aged 18–89 years found that OAB was reported by 31.8% of participants and had a severe effect on their QoL. OAB symptoms were assessed by the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire Overactive Bladder (ICIQ‐OAB) and followed the ICS definitionCitation12. Another study conducted in Porto Alegre, Brazil reported that OAB, according to the ICS definition, affected 18.9% of 848 individuals aged 15–55 years, with a statistically significantly greater incidence in females (23.2%) than males (14%)Citation14. This study also reported statistically significant impairment associated with OAB in terms of daily activities, including social, work and sexual function. More recently, data from the first, large population-based study to evaluate LUTS in Brazil (Brazil LUTS)Citation15 revealed an overall prevalence of LUTS of 75%, including 69% in men and 82% in women. The study included 5184 participants aged ≥40 years from five main cities. In total 24.4% of patients, including 24.5% of men and 24.4% of women, had a possible diagnosis of OAB, based on the OAB-V8 questionnaire, which requires a score of 8 or more points to qualifyCitation16. Collectively, these data suggest there is a substantial burden of OAB in Latin America, with some evidence to indicate its important impact on QoL and low rates of treatment-seeking behavior, especially among older peopleCitation15. Moreover, a paper on the impact of LUTS on treatment-related behaviors and QoL showed that treatment seeking and treatment rates for LUTS are lowCitation17.

The primary objective of the present study was to evaluate, in a Brazilian population reporting symptoms of OAB, the effect of individual LUTS and LUTS-specific bother on daily/leisure activities, work productivity and treatment behaviors (treatment seeking, receiving treatment, treatment dissatisfaction and treatment discontinuation).

Methods

Study design and patients

This was a secondary analysis of data from the cross-sectional epidemiological Brazil LUTS study, with full details of the study design and patient population previously publishedCitation15 and presented briefly here. Initially, 10,000 telephone numbers were selected by systematic randomization for municipalities of São Paulo, Porto Alegre, Recife, Belém and Goiânia, the randomized selection being stratified by zip code to ensure equal representation by location. Once households were identified, individuals resident in the household and aged ≥40 years were contacted by the interviewer, who explained the purpose of the research and requested verbal informed consent from these individuals. Questions asked during the telephone survey regarding the impact of LUTS on QoL (IPSS question 8), treatment seeking, treatment, treatment satisfaction, and treatment discontinuation are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

The study included a total of 5184 individuals aged ≥40 years with residential landlines and living in Brazil’s geographical regions South East (São Paulo; n = 1004), South (Porto Alegre; n = 1002), North East (Recife; n = 1013), North (Belém; n = 1004) or Central West (Goiânia; n = 1161), who answered the full interview. Participants completed a computer-assisted telephone survey between September 1 and December 31, 2015. Exclusions included pregnant women and individuals (men and women) who reported having either a current or previous (within one month) urinary tract infection (UTI).

The study received approval from a local ethics committee (Ethics Committee of Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo) and was compliant with good clinical practice and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data collection

The questionnaire applied in this study was developed based on the definitions of individual LUTS by the International Continence Society standardization of terminology of LUTS (ICS-2002)Citation18, and included the questionnaires, the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS)Citation19 and the Overactive Bladder–Validated 8-question Screener (OAB-V8), both validated in Portuguese. LUTS evaluated included slow stream, splitting, intermittency, hesitancy, straining, terminal dribble, perceived frequency, urgency, urgency with fear of leaking, UUI, stress urinary incontinence (SUI), leak for no reason, nocturnal enuresis, leak during sexual activity, incomplete emptying and post-micturition dribbleCitation2. Mixed urinary incontinence was defined as the co-presence of UUI and SUI. The latter was assessed by the specific question: “During the past 4 weeks, did you leak urine in connection with laughing, sneezing, or coughing, physical activities, such as exercising or lifting a heavy object?” This present analysis considers data only from those participants who had a possible diagnosis of OAB, based on a score of ≥8 on the OAB-V8 questionnaire, and includes patients with and without UUICitation15,Citation16. The OAB-V8 score was used for dichotomizing individuals, based on a score of ≥8 to qualify as a possible diagnosis of OAB. OAB-V8 score was not used for means or any type of summary statistics. Participants used a Likert scale (Score 1–5) to rate: occurrence of their LUTS during the previous month (none [0], less than 1 in 5 times [1], less than half the time [2], about half the time [3], more than half the time [4], or almost always [5]); and also the bother associated with their LUTS (not at all [0], a little bit [1], somewhat [2], quite a bit [3], a great deal [4], or a very great deal [5]). These scales were applied to all LUTS included in the questionnaire. Telephone interviews were conducted by a local market research company.

Endpoints

The primary study objective was to investigate the impact of individual LUTS on specific outcomes in the population reporting OAB symptoms. Specifically, this was to investigate the impact of LUTS on work productivity, leisure and daily activities, and to investigate the impact of LUTS on treatment-seeking behaviors and treatment satisfaction in the population reporting symptoms of OAB. The primary objective for this analysis was pre-specified in the statistical analysis plan, before the survey was undertaken.

Statistical methods

Sample size was calculated based on the population age, distribution and expected LUTS prevalence rates (men: 17–30% and women: 17.8–22.5%)Citation15. Given a coefficient of variation of 0.15, a sample size of 1000 interviews per city was required to obtain the sample size needed for estimating prevalence of LUTS. The sample size calculation estimated an effective minimum sample of 5000 respondents. In order to achieve this number, it was necessary to perform a higher number of calls and interviews, assuming a rate of non-eligibility, refusals and non-completion of the interview. To reduce potential selection bias, when estimating the prevalence of LUTS, data underwent post-stratification adjustment matching respondents’ distribution by age, sex, and education to that observed for each city’s population in the 2010 census. Missing at random was assumed in this study. This study was performed via complex samples. Therefore, the sample weight differs between individuals according to region (strata and size of cluster).

Associations between categorical variables were measured using Pearson’s chi-squared test and descriptive statistics were used to obtain a general understanding of the data collected and the characteristics of the sample studied. Logistic regression (non-linear) models were constructed to analyze the association of symptom frequency and symptom bother, controlled for demographics, comorbid condition, habits and body mass index, to outcomes related to people’s lives and treatment patterns. Parameters included in the models were age, education level, working status, marital status, nutritional state, smoking, physical activity level, depression/anxiety, diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, intestinal constipation, dyslipidemia and LUTS. The reported p-values are descriptive, not hypothesis-testing. The multistage area probability designs of this study include clustering, stratification, and the assignment of unequal probabilities of selection to sample units. The complexity of these sample designs causes a departure from the assumption that independent sample points have equal probabilities of selection. Specialized statistical software was used to accurately compute estimates of population statistics and their standard errors; otherwise, the standard errors produced, as for a simple random sample, would generally underestimate the true population value, negating the validity of resulting confidence intervals or statistical significance tests. All statistical analyses took the sample plan into account and were performed using SPSS version 20 for Windows (Complex Samples Module).

Results

OAB: impact on personal domains and treatment patterns

A total of 17,600 telephone call were made, and 11,483 individuals met the eligibility criteria (≥40 years of age, who were resident in the home, not pregnant and with no UTIs within the past month). Out of those, 2959 individuals refused (26%), and 3340 (29%) did not complete the interview for other reasons (rescheduled interviews, interrupted calls, calls not answered). Consequently, 5184 individuals (45%) completed the interviewCitation15 (Supplementary Figure 1). Out of them, 24.4% (n = 1266), including 596 men and 670 women, met the criteria for a possible diagnosis of OAB based on the OAB-V8 questionnaire. In this subgroup, 6.5% (n = 39) of men and 36.5% (n = 246) women (22.4% [n = 284] overall) had mixed urinary incontinence involving urinary leakage with SUI in addition to urge. There was no evidence of an association between gender and OAB, with a similar proportion of participants with OAB among age groups for both sexes; however, OAB wet was statistically significantly more common in women (61%; n = 409) than men (38.4%; n = 228), p<.001.

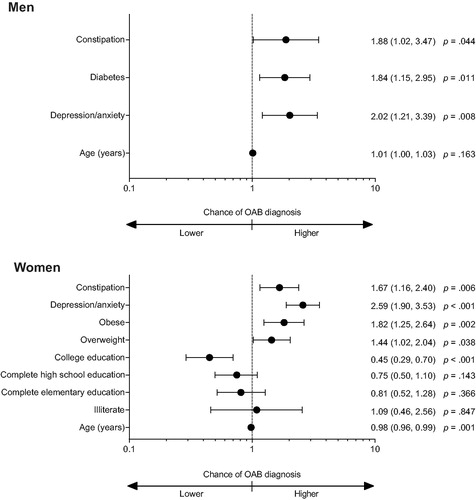

Demographic factors and comorbidities associated with the possible diagnosis of OAB in men and women are shown in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3, respectively. Considering all participants, the possible diagnosis of OAB in men was twice as likely among those who reported comorbid depression/anxiety (p=.008), 1.9 times as likely in those with constipation (p=.044) and 1.8 times as likely in those with diabetes mellitus (p=.011) (). Similarly, the possible diagnosis of OAB in women was 2.6 (p<.001) and 1.7 (p=.006) times as likely among those with comorbid depression/anxiety or constipation, respectively (). Women who were obese or overweight also had a higher risk of presenting symptoms of OAB (1.8; p=.002 and 1.4 times; p=.038 respectively). Conversely, women with a college education had a 0.4 times likelihood of a possible diagnosis of OAB (p<.001), whereas there was little difference in likelihood of that among women who had completed high school or elementary school compared to women who had incomplete elementary school.

Figure 1. Association of demographic factors and comorbidities with overactive bladder in men and women. Abbreviation. OAB, overactive bladder. Statistically non-significant data are not shown.

Treatment seeking for symptoms of OAB was low among men and women overall (35.1 and 43.6%, respectively), with the highest rate among individuals in the 60–69 age group ( and ). Likewise, rates of treatment for symptoms of OAB had a similar pattern as treatment seeking for men and women, with slightly more women overall (37.3%) seeking treatment than men (29.1%). Treatment satisfaction was achieved in 66.1% of men and 65.9% of women and was more common in older patients, including 65–75% of men ≥60 years and 80% of women ≥70 years. Median OAB-V8 scores were similar among age groups in men and women, except for women aged 60–69 years. The statistically significant results of the logistic regression models on the impact of individual LUTS and socio-demographic characteristics on personal domains in men and women with OAB symptoms are presented in detail below and in forest plots, including odds ratios and 95% CIs (). Complete logistic regression tables can be found in Supplementary Table 4.

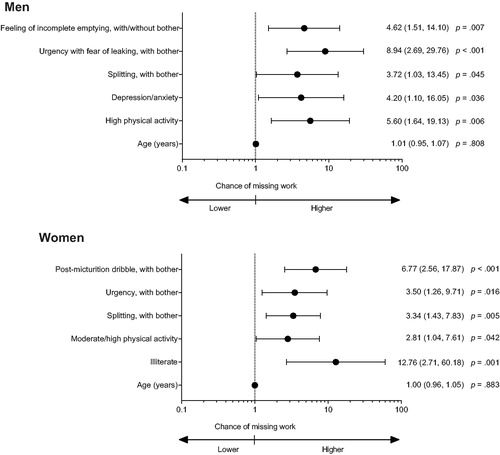

Figure 2. Chance of missing work in men and women with a possible diagnosis of overactive bladder: forest plot of multiple regression models; adjusted odds ratios (95% CI). Statistically non-significant data are not shown.

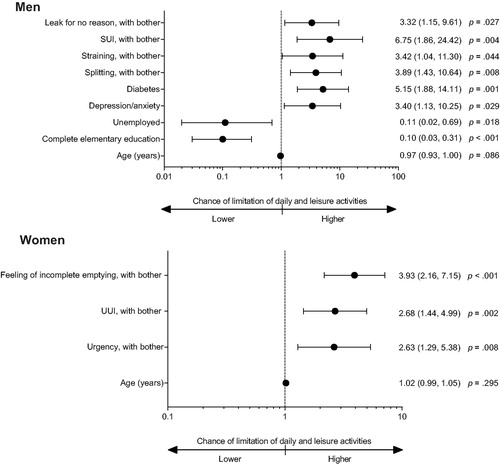

Figure 3. Chance of limitation of daily and leisure activities in men and women with a possible diagnosis of overactive bladder: Forest plot of multiple regression models; adjusted odds ratios (95% CI). Abbreviations. CI, confidence interval; SUI, stress urinary incontinence; UUI, urgency urinary incontinence. Statistically non-significant data are not shown.

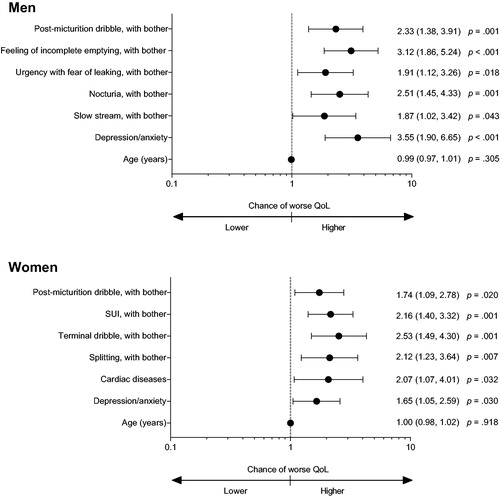

Figure 4. Chance of worse QoL due to LUTS in men and women with a possible diagnosis of overactive bladder: Forest plot of multiple regression models; adjusted odds ratios (95% CI). Abbreviations. CI, confidence interval; LUTS, lower urinary tract symptoms; QoL, quality of life; SUI, stress urinary incontinence. Statistically non-significant data are not shown.

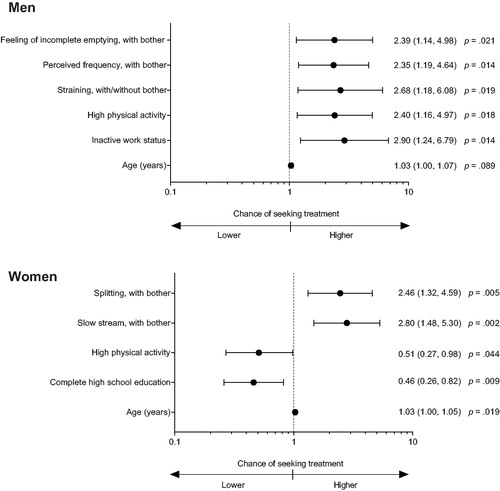

Figure 5. Chance of seeking treatment in men and women with a possible diagnosis of overactive bladder: Forest plot of multiple regression models; adjusted odds ratios (95% CI). Abbreviations. CI, confidence interval. Statistically non-significant data are not shown.

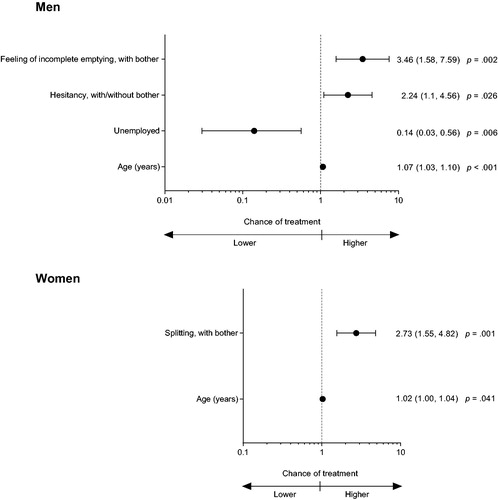

Figure 6. Chance of treatment in men and women with a possible diagnosis of overactive bladder: Forest plot of multiple regression models; adjusted odds ratios (95% CI). Abbreviations. CI, confidence interval. Statistically non-significant data are not shown.

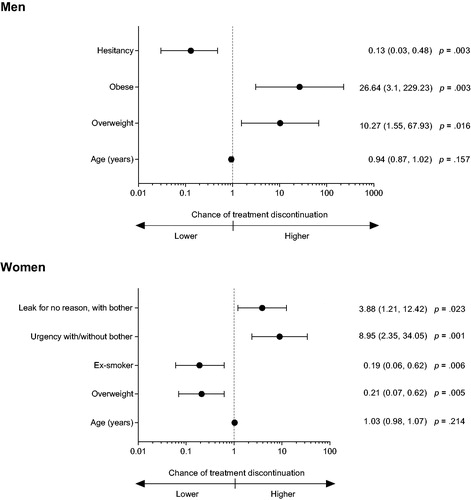

Figure 7. Chance of treatment discontinuation in men and women with a possible diagnosis of overactive bladder: Forest plot of multiple regression models; adjusted odds ratios (95% CI). Abbreviations. CI, confidence interval. Statistically non-significant data are not shown.

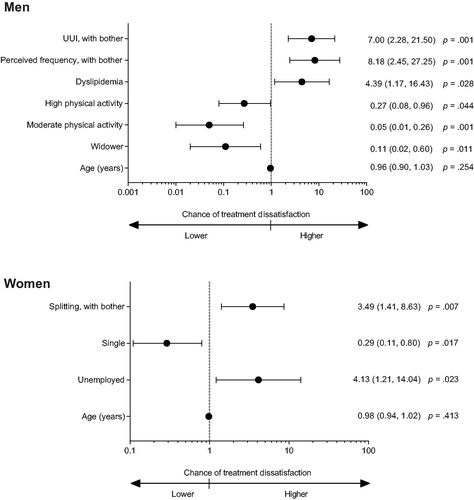

Figure 8. Chance of treatment dissatisfaction in men and women with a possible diagnosis of overactive bladder: Forest plot of multiple regression models; adjusted odds ratios (95% CI). Abbreviations. CI, confidence interval; UUI, urgency urinary incontinence. Statistically non-significant data are not shown.

Table 1. Impact of OAB on work, daily and leisure activities; treatment seeking, treatment, treatment satisfaction and treatment discontinuation by age in men with a possible diagnosis of OAB.

Table 2. Impact of OAB on work, daily and leisure activities; treatment seeking, treatment, treatment satisfaction and treatment discontinuation by age in women with a possible diagnosis of OAB.

Work absence

In men with a possible diagnosis of OAB, a higher chance of missing work due to LUTS was seen in those reporting high physical activity (5.6 times; p = .006), depression/anxiety (4.2 times; p=.036), urgency with fear of leaking (8.9 times; p < .001), feeling of incomplete emptying (4.6 times; p = .007) or bother associated with splitting (3.7 times; p = .045). In women with a possible diagnosis of OAB, the likelihood of missing work due to LUTS was markedly increased in those with illiteracy (12.8 times vs. women with incomplete elementary education; p = .001), moderate/high physical activity (2.8 times vs. sedentary women; p = .042), post-micturition dribble (6.8 times; p < .001), urgency (3.5 times; p = .016) or bother associated with splitting (3.3 times; p = .005) ().

Limitation of daily and leisure activities

In men with a possible diagnosis of OAB, limitation of daily and leisure activities due to LUTS was increased by 5.1 times in those with diabetes (p = .001), 3.4 times in those reporting depression/anxiety (p = .029), and 6.7 times in those with SUI (p = .004), 3.9 times in those with bother associated with splitting (p = .008), 3.4 times in those with straining (p = .044), and 3.3 times in those with leak for no reason (p = .027). Conversely, a lower chance of limitation of daily and leisure activities was seen in men with complete elementary education (0.10 times; p < .001) or who were unemployed (0.11 times; p = .018). In women with a possible diagnosis of OAB, the chance of limitation of daily and leisure activities due to LUTS was increased by 3.9 times in those with a feeling of incomplete emptying (p < .001), 2.7 times in those with UUI (p = .002) and 2.6 times in those reporting bother associated with urgency (p = .008) ().

Effect on QoL due to LUTS

Quality of life in men and women with a possible diagnosis of OAB was also negatively impacted by urinary symptoms. In men with a possible diagnosis of OAB, the likelihood of worse QoL due to LUTS was increased among those with depression/anxiety (3.5 times; p < .001). LUTS associated with a higher chance of worse QoL included feeling of incomplete emptying (3.1 times; p < .001), nocturia (2.5 times; p = .001), post-micturition dribble (2.3 times; p = .001), urgency with fear of leaking (1.9 times; p = .018) and bother associated with slow stream (1.9 times; p = .043). In women with a possible diagnosis of OAB, the likelihood of worse QoL due to LUTS was increased, albeit to a lesser extent, among those with depression/anxiety (1.6 times; p = .030), cardiac diseases (2.1 times; p = .032), bother associated with terminal dribble (2.5 times; p = .001), SUI (2.2 times; p = .001) splitting (2.1 times; p = .007), and post-micturition dribble (1.7 times; p = .020) ().

Treatment seeking

In men, the likelihood of seeking treatment was increased among those reporting inactive work status (2.9 times; p = .014), high physical activity (2.4 times; p = .018), straining with or without bother (2.7 times; p = .019), and those with bother associated with feeling of incomplete emptying (2.4 times; p = .021) or perceived frequency (2.3 times; p = .014). In women, the likelihood of seeking treatment was slightly increased for each additional year of life (1.0 times; p = .019), and for those with bother associated with slow stream (2.8 times; p = .002) and splitting (2.5 times; p = .005). Conversely, the chance of seeking treatment was decreased among those women who completed their high school education (0.46 times; p = .009) and for those who reported high physical activity (0.51 times; p = .044) ().

Factors affecting treatment

The likelihood of men with a possible diagnosis of OAB receiving treatment was decreased in the unemployed (0.14 times; p = .006) compared with men who were employed and was statistically significantly increased for each additional year of life (1.1 times; p < .001). Men reporting bother associated with the feeling of incomplete emptying or hesitancy with or without bother had a 3.5 times (p = .002), and 2.2 times (p = .026) increased likelihood of receiving treatment, respectively. In women with a possible diagnosis of OAB, the likelihood of receiving treatment also increased with each additional year of life (1.0 times; p = .041) and with bother associated with splitting (2.7 times; p = .001) ().

Treatment discontinuation

The likelihood of treatment discontinuation in men with a possible diagnosis of OAB was markedly increased in those who were overweight (10.3 times; p = .016) or obese (26.6 times; p = .003), and was decreased by 87% lower in those reporting hesitancy (p = .003). In women with a possible diagnosis of OAB, the likelihood of treatment discontinuation was increased among those with urgency with or without bother (8.9 times; p = .001) and bother associated with leak for no reason (3.9 times; p = .023). The chance of treatment discontinuation decreased was 0.19 times among women who were ex-smokers (p = .006) and 0.21 times in those who were overweight (p = .005) compared to women without these conditions ().

Treatment dissatisfaction

The likelihood of treatment dissatisfaction in men was increased among those with dyslipidemia (4.4 times; p = .028), and with perceived frequency with bother (8.2 times; p = .001), and UUI with bother (7.0 times; p = .001). The likelihood of treatment dissatisfaction was 0.05 and 0.27 times among men reporting moderate (p = .001) or high physical activity (p = .044), respectively, and 0.11 times in those widowed (p = .011) compared to men without these conditions. In women with a possible diagnosis of OAB, the likelihood of treatment dissatisfaction was increased among those who were unemployed (4.1 times; p = .023) or who reported bother associated with splitting (3.5 times; p = .007), and 0.29 times among those who were single (p = .017) () compared to women without these conditions.

Discussion

In this secondary analysis of data from the Brazil LUTS studyCitation15, in which a random sample of adults aged ≥40 years with symptoms of OAB identified using the OAB-V8 questionnaire were evaluated for the impact of LUTS on work, QoL and treatment-related outcomes, we not only observed a high prevalence of OAB (24.4%), but also a statistically significant association between OAB and self-reported comorbid depression/anxiety and constipation in both men and women. This analysis also shows that for both men and women, the likelihood of missing work, experiencing limitations in daily living/leisure, worse QoL and treatment-seeking behavior was markedly increased with the presence of specific LUTS associated with a possible diagnosis of OAB. Moreover, in both men and women, the likelihood of worse QoL due to LUTS was increased with comorbid depression/anxiety whereas the chance of missing work due to LUTS was also increased among those reporting high physical activity. Missing work and missing leisure/impacting daily activities was more prevalent in women (men: 2 and 15%; women: 6 and 26%, respectively). Collectively, these findings emphasize the need for proper assessment of comorbidities and burden of LUTS among patients with OAB.

The association between OAB and comorbid depression/anxiety and constipation was previously observed in the EPICCitation1, EpiLUTSCitation2 and Asian OABCitation20 studies, which found that asthma, diabetes, high blood pressure, bladder cancer, prostate cancer and neurological conditions (such as multiple sclerosis or Parkinson’s disease) were associated with OAB, suggesting that OAB is typically associated with a high comorbidity burden. Although the findings in this current analysis suggest that both men and women engage in help-seeking behavior particularly when LUTS are bothersome, and that the impact on QoL was high in individuals reporting OAB symptoms, the rates of treatment seeking were low for both sexes at 35.1% of men and 43.6% of women, with decreased likelihood in these unemployed and increased likelihood with every year of life. A similar rate of treatment seeking was reported in the EPIC study, with 38% of patients seeking treatmentCitation21. Likewise, in the MexiLUTS study, surprisingly few (14.6%) men sought treatment, despite the frequency and bother due to LUTS, and the relatively high education level in this cohort (75% had at least high school education)Citation22. There are numerous reasons for such variation in reported rates of treatment seeking in patients with OAB, including study design, cultural stigma and belief that LUTS are a natural occurrence with aging and are not treatable or curableCitation23. However, it is interesting that a report from Sweden based on two population-based surveys of women undertaken 16 years apart (1991 and 2017) suggests that the low rates of treatment seeking behavior observed in a developed country have not improved over time, despite statistically significantly more women (29 vs. 13%; p < .001) reporting that urinary symptoms limited their social lifeCitation24. This finding suggests that there is an ongoing need to improve the awareness of those with OAB, as well as healthcare professionals involved in providing treatment.

Although the prevalence of a possible diagnosis of OAB, based on an OAB-V8 score ≥8, was similar for men and women in our study, we observed a >20% higher prevalence of OAB wet among women than men. Similar results have been reported in the United States, with the NOBLE study revealing a similar age-specific prevalence of OAB in men and women, with differences emerging in terms of type of OAB by sex and, notably, a higher prevalence of OAB with urge incontinence in women compared with menCitation4.

In both men and women, symptoms of all three LUTS categories of voiding, storage, and post-micturition, and not only those storage symptoms of OAB, were associated with all domains of the analyses, including limitations on daily and leisure activities, work absenteeism, worse QoL and treatment-related outcomes. These findings emphasize the importance of effective symptom management in patients with OAB in order to prevent the substantial negative impact of the disorder. Currently, in males with LUTS, management tends to focus on voiding symptoms, whereas patients with such symptoms typically find storage symptoms more bothersomeCitation24. Thus, for management to be effective, consideration needs to be given to all categories of symptoms, including impact, mechanism and treatment options with focus on a personalized management approachCitation25.

The main strengths of this analysis include its large sample size and geographically diverse population, which permits generalization of the data to different regions in Brazil. The numbers of male and female participants were balanced, which further adds external validity to the study sample. This analysis also has limitations, including the nature of the data capture and the major limitation relating to self-reporting of OAB in the absence of a confirmed clinical diagnosis of OAB, self-reporting of comorbidities and treatments, and that no details about treatment or drug‐related adverse events were explored. To evaluate the impact of missing data on prevalence, tracking some cases would be required to understand characteristics of this group of individuals. However, due to the nature of our study, this is not possible. Reliance on the OAB-V8 instrument used to define the study sample means that it is not possible to exclude LUTS secondary to other conditions unrelated to OAB, such as 24-hour polyuria, nocturnal polyuria or other conditions that could cause dysfunction of the lower urinary tract.

Conclusions

This secondary analysis of data from the population-based Brazil LUTS study underlines the importance of comprehensive assessment of symptoms, and especially the related bother, in order to ensure appropriate and personalized management of men and women with suspected OAB/LUTS. Assessment should include symptoms relating to storage, voiding and post-micturition, since all were associated in the present study with detrimental impacts on work, daily living, QoL and other domains. Despite the high rate of bother and the impact on QoL in those reporting OAB symptoms, treatment seeking was low. Therefore, there is a need for increased awareness among patients of OAB/LUTS in order to improve treatment-seeking behavior and therefore the adequate management of this distressing disorder.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Astellas Pharma Brazil.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

CMG is a consultant/speaker for Astellas Pharma Brazil, Boston Scientific, and Zodiac Brazil; has received study grants from Ipsen; and is a proctor for Medtronic. MA is a consultant/researcher for Astellas Pharma Brazil and Ipsen; a consultant for GSK Brazil and Coloplast; and is a proctor for Medtronic. MK is a consultant for Astellas Pharma Brazil. RS is an employee of Astellas Pharma Brazil. A peer reviewer on this manuscripts discloses that, in the OAB field, they are a consultant to Apogepha, Astellas, and Velicept, as well as a shareholder of Velicept. The other peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

Conception and design: CMG, MAA and RS. Data analysis and interpretation: CMG, MAA, MK and RS.

Manuscript drafting: CMG, MAA, MK and RS. Critical revision for intellectual content: CMG, MAA, MK and RS. Final approval of manuscript: CMG, MAA, MK and RS.

Supplemental OAB Models

Download MS Word (547.2 KB)Supplemental Table 3

Download MS Word (20.4 KB)Supplemental Table 2

Download MS Word (18.6 KB)Supplemental Table 1

Download MS Word (14.1 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (96.3 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (260.8 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants of the study for their time. Editorial support, including writing assistance, was provided by Sue Cooper of Envision Scientific Solutions, funded by Astellas Pharma.

Data availability

Access to anonymized individual participant level data will not be provided for this trial as it meets one or more of the exceptions described on www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com under “Sponsor Specific Details for Astellas”.

References

- Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Irwin DE, et al. The impact of overactive bladder, incontinence and other lower urinary tract symptoms on quality of life, work productivity, sexuality and emotional well-being in men and women: results from the EPIC study. BJU Int. 2008;101(11):1388–1395.

- Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Thompson C, et al. The impact of OAB on sexual health in men and women: results from EpiLUTS. J Sex Med. 2011;8(6):1603–1615.

- Abrams P, Kelleher CJ, Kerr LA, et al. Overactive bladder significantly affects quality of life. Am J Manag Care. 2000;6(11 Suppl):S580–S590.

- Stewart WF, Van Rooyen JB, Cundiff GW, et al. Prevalence and burden of overactive bladder in the United States. World J Urol. 2003;20(6):327–336.

- Errando-Smet C, Müller-Arteaga C, Hernández M, et al. Healthcare resource utilization and cost among males with lower urinary tract symptoms with a predominant storage component in Spain: The epidemiological, cross-sectional MERCURY study. Neurourol Urodyn. 2018;37(1):307–315.

- Irwin DE, Milsom I, Hunskaar S, et al. Population-based survey of urinary incontinence, overactive bladder, and other lower urinary tract symptoms in five countries: results of the EPIC study. Eur Urol. 2006;50(6):1306–1314.

- Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Vats V, et al. National community prevalence of overactive bladder in the United States stratified by sex and age. Urology. 2011;77(5):1081–1087.

- Van Den Eeden SK, Shan J, Jacobsen SJ, Urologic Diseases in America Project, et al. Evaluating racial/ethnic disparities in lower urinary tract symptoms in men. J Urol. 2012;187(1):185–189.

- Abreu GE, Dourado ER, Alves DN, et al. Functional constipation and overactive bladder in women: a population-based study. Arq Gastroenterol. 2018;55(Suppl 1):35–40.

- Faria CA, Moraes JR, Monnerat BR, et al. Effect of the type of urinary incontinence on the quality of life of patients in the public healthcare system in Southeastern Brazil. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2015;37(8):374–380.

- Moreira ED, Jr, Neves RC, Neto AF, et al. A population-based survey of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and symptom-specific bother: results from the Brazilian LUTS epidemiology study (BLUES). World J Urol. 2013;31(6):1451–1458.

- Plata M, Bravo-Balado A, Robledo D, et al. Prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms and overactive bladder in men and women over 18 years old: the Colombian overactive bladder and lower urinary tract symptoms (COBaLT) study. Neurourol Urodyn. 2019;38(1):200–207.

- Rios AA, Cardoso JR, Rodrigues MA, et al. The help-seeking by women with urinary incontinence in Brazil. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22(7):879–884.

- Teloken C, Caraver F, Weber FA, et al. Overactive bladder: prevalence and implications in Brazil. Eur Urol. 2006;49(6):1087–1092.

- Soler R, Gomes CM, Averbeck MA, et al. The prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in Brazil: results from the epidemiology of LUTS (Brazil LUTS) study. Neurourol Urodyn. 2018;37(4):1356–1364.

- Coyne KS, Zyczynski T, Margolis MK, et al. Validation of an overactive bladder awareness tool for use in primary care settings. Adv Therapy. 2005;22(4):381–394.

- Soler R, Averbeck MA, Koyama MAH, et al. Impact of LUTS on treatment-related behaviors and quality of life: a population-based study in Brazil. Neurourol Urodyn. 2019;38(6):1579–1587.

- Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002;21(2):167–178.

- Barry MJ, Fowler FJ, Jr., O’Leary MP, The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association, et al. The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 1992;148(5 Part 1):1549–1557.

- Chuang YC, Liu SP, Lee KS, et al. Prevalence of overactive bladder in China, Taiwan and South Korea: Results from a cross-sectional, population-based study. Low Urin Tract Symptoms. 2019;11(1):48–55.

- Irwin DE, Milsom I, Kopp Z, et al. Symptom bother and health care-seeking behavior among individuals with overactive bladder. Eur Urol. 2008;53(5):1029–1037.

- Gonzalez-Sanchez B, Cendejas-Gomez J, Alejandro Rivera-Ramirez J, et al. The correlation between lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and erectile dysfunction (ED): results from a survey in males from Mexico City (MexiLUTS). World J Urol. 2016;34(7):979–983.

- Chapple C, Castro-Diaz D, Chuang YC, et al. Prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms in China, Taiwan, and South Korea: results from a cross-sectional, population-based study. Adv Ther. 2017;34(8):1953–1965.

- Wennberg AL, Molander U, Fall M, et al. Lower urinary tract symptoms: lack of change in prevalence and help-seeking behaviour in two population-based surveys of women in 1991 and 2007. BJU Int. 2009;104(7):954–959.

- Chapple CR, Drake MJ, Van Kerrebroeck P, et al. Total urgency and frequency score as a measure of urgency and frequency in overactive bladder and storage lower urinary tract symptoms. BJU Int. 2014;113(5):696–703.