Abstract

17α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17-OHPC; MAKENA and generic equivalents) is the only FDA-approved medicine available to reduce the risk of preterm birth (PTB) in pregnant women with a singleton pregnancy who have a history of singleton spontaneous PTB. The FDA held an Advisory Committee meeting in October 2019 to review conflicting data between one positive U.S.-based study and one international study that failed to confirm the benefit. At this meeting, the key vote as to whether the FDA should pursue withdrawal of Makena resulted in a split; 9 members voted that the FDA pursue withdrawal and 7 members voted to leave Makena on the market and require that additional effectiveness data be generated. Removal of FDA-approved formulations of 17-OHPC—both brand name Makena and the generic equivalents—would foreseeably result in clinicians administering compounded 17-OHPC to prevent PTB in their patients. Unlike FDA-approved products, compounded drugs are not approved by the FDA and, thus, have not undergone any FDA scrutiny with regard to safety, effectiveness, or quality (as designated by good manufacturing practices; GMP) before they are marketed. Compounded drugs may be associated with significant safety risks, as poor compounding practices have resulted in serious problems with drug quality (lack of sterility or stability) and potency. Given the markedly higher rates of PTB in the U.S. compared with other industrialized nations, it is imperative that FDA-approved, GMP-produced 17-OHPC (FDA-approved brand and generic formulations) is available while additional research on its optimal use is conducted, without providers and patients resorting to pharmacist-compounded formulations for their high-risk pregnant patients.

Introduction

Because few medications are specifically FDA-approved to be used in pregnancy, healthcare providers in this therapeutic area must often prescribe medications “off-label,” i.e. outside of an FDA approval that has determined a medication to be both safe and effective for a particular indication. This means providers are prescribing medications that are FDA-approved for an indication in non-pregnant patients, but without FDA-sanctioned safety and efficacy data to support use specifically during pregnancy. While potentially concerning for patients and clinicians, this is not altogether surprising, since women were not routinely allowed in clinical trials until the 1990sCitation1. Pregnancy poses a particular challenge for researchers and regulatory authorities, as there are two patients (mother and fetus) for whom safety and efficacy must be considered.

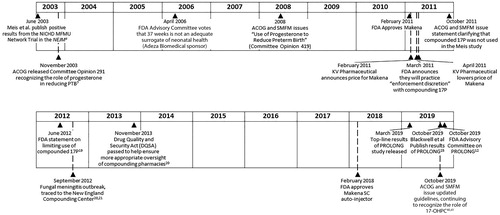

In the U.S., about 10% of pregnancies are preterm, defined as delivery less than 37 weeks of gestationCitation2. The majority of these preterm births are nulliparous. However, among women who are multiparous, it has long been recognized that a significant specific risk factor for a preterm birth (PTB) is having had a prior spontaneous preterm delivery, which increases the risk of a subsequent PTB by at least 2-foldCitation3. In 2003, the Maternal Fetal Medicine Unit (MFMU) Network published their landmark study, supported by the National Institutes of Health and Human Development (NICHD) by Meis et al.Citation4 This study, conducted at 19 academic centers in the U.S. between 1999 and 2002, demonstrated that weekly intramuscular injections of 17α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17-OHPC) reduced the risk of a recurrent preterm birth (PTB) in women with a history of spontaneous singleton preterm birth by one-third compared with placebo (). Meis reported that the number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent one preterm birth less than 37 weeks of gestation was 5.4. While the study was not powered to detect improvement in overall neonatal outcomes, the Meis et al. publication reported reductions in intraventricular hemorrhage Grade 3 and 4, necrotizing enterocolitis and supplemental oxygen (p < .05) in the 17-OHPC group compared with placeboCitation4.

The results of the Meis trial have been criticized because the rate of PTB <37 weeks was 54.9% in the placebo group, which was higher than projected based on previous researchCitation5. However, this rate of preterm birth would not be unexpected given the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the study participants; approximately 59% of women in the study were black, the mean gestational age of the qualifying PTB was approximately 31 weeks, and approximately 30% of women had >1 prior PTBCitation4. Maternal race (black vs non-black), gestational age of the index preterm birth, and number of previous PTB are risk factors that each confers a 1.5- to 2-fold increase in the risk of recurrent preterm birth beyond the 1.5- to 2-fold risk associated with a prior PTBCitation6.

While the overall demographic and clinical characteristics of patients in the Meis trial were balanced between treatment groups, there were significantly more prior PTBs at baseline in the placebo group compared to the 17-OHPC group (mean, 1.6 vs 1.4; p = .007). Because of this imbalance between the 17-OHPC and placebo groups, the data were analyzed with adjustment for the number of previous preterm deliveriesCitation4. The adjusted relative risk (RR) of delivery at <37 weeks of gestation in the 17-OHPC group compared with the placebo group was 0.70 (95% CI, 0.57–0.85, p < .001). In addition, 17-OHPC reduced PTB in subgroups of patients with >1 prior preterm birth (RR = 0.68; 95% CI, 0.52–0.90) and patients with only 1 prior preterm birth (RR = 0.72; 95% CI, 0.53–0.97).

As this was the first rigorously conducted, multicenter U.S. study to demonstrate that an intervention could positively impact one of the groups most at-risk for a preterm birth (i.e. women with a history of spontaneous PTB), adoption of the use of 17-OHPC was rapid, despite the initial absence of a commercially available FDA-approved product. The same year Meis and colleagues published their findings, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) released a Committee Opinion recognizing the role of progesterone in reducing PTBCitation7. ACOG also noted that a small single-center study in Brazil of vaginal progesterone in “high-risk” women (the majority of whom had a prior PTB) reported a reduction in subsequent PTBCitation8.

When ACOG published their opinion, they noted that the Meis trialCitation3 study drug was specially formulated and not commercially availableCitation7. As an alternative, providers turned to pharmacist-compounded formulations of 17-OHPC to administer to their patients who had previously delivered preterm. In a 2005 survey of 572 Maternal Fetal Medicine (MFM) specialistsCitation9, 67% of respondents had used progesterone to prevent PTB, with 87% noting a preference for weekly intramuscular (IM) administration while 13% preferred daily vaginal progesterone. In a 2007 survey of 345 obstetriciansCitation10, 74% recommended or offered progesterone for PTB; similar to the MFM survey, the majority (83%) of obstetricians preferred weekly IM administration while 9% preferred vaginal progesterone.

While these publicationsCitation9,Citation10, as well as the initial ACOG GuidelineCitation7, referred to “progesterone,” it is important to clarify nomenclature. Intramuscular progesterone is not FDA approved for prevention of PTB, nor has it been studied for this purpose. In contrast, 17-alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17-OHPC) is a progestin, i.e. structurally related to progesterone. The MFMU selected 17-OHPC as the agent to study in their landmark study based upon a 1990 meta-analysis by KeirseCitation11, in which he restricted inclusion of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to those of 17-OHPC, as this was the most well-studied progestational agent for history of prior PTB. This meta-analysis demonstrated a 42% reduction in the rate of recurrent PTB with 17-OHPCCitation11.

FDA review and approval of Makena (17-OHPC)

The regulatory process at FDA is one of the most stringent in the world, and healthcare providers and patients benefit from this rigor. FDA approval of a medication involves an independent and thorough review that determines if a product is both safe and effective for a specific indication, and a comprehensive evaluation by FDA to ensure that product is manufactured in accordance with GMP and meets FDA’s quality standards. The pathway to FDA approval is often lengthy, and the approval of 17-OHPC to prevent PTB was first considered at a 2006 Advisory Committee with Adeza Biomedical as the sponsor ()Citation12. A majority of the advisory committee (16 members) voted that reduction of PTB <37 weeks gestation, which was the primary endpoint in the MFMU Meis trial, was not an adequate surrogate to predict neonatal morbidity and mortality, while 5 committee members voted that <37 weeks was an adequate surrogate. When asked whether 35 weeks was an adequate surrogate, 13 members voted yes and 8 voted noCitation12.

In a subsequent review in 2011, the FDA reassessed the gestational age issues, noting multiple clinical studies had documented adverse consequences of “late preterm birth” (births between 34 and 36 6/7 weeks gestation), as these infants are less physiologically and metabolically mature than infants born at full term (39–40 weeks) and therefore are at a higher risk of morbidity and mortalityCitation12. Based on this, the FDA then determined PTB <37 weeks was an acceptable surrogate endpoint that reasonably could predict clinical benefit.

During this 2011 review, the FDA medical reviewer also noted the following:

“Finally, of significant concern, is the fact that several national surveys have indicated that a large number of obstetricians currently treat pregnant women with compounded 17-HPC, which is not available as an FDA-regulated, Good Manufacturing Process (GMP)-produced product.”Citation13

The FDA has historically had comprehensive regulatory purview over only those drugs that they review/approve, i.e. brand name and generic medications, leaving oversight of pharmacy compounding largely to individual State Boards of Pharmacy. Under the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act), pharmacist-compounding has been limited to those unique situations of “medical need,” where an individual patient is unable to use an approved dosage form, such as a a pediatric or geriatric patient needing a tablet compounded into a solution, or a medication compounded to remove a particular component due to allergyCitation14. In this situation, a so-called “triad relationship” exists between the individual patient, the prescribing clinician and the pharmacist, in stark contrast to drugs used in the general populationCitation14.

In 2011, 17-OHPC was granted FDA-approval to reduce recurrent PTB under the trade name Makena (hydroxyprogesterone caproate injection), which is currently manufactured by AMAG Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (). When the product was initially launched by KV Pharmaceutical, there was considerable controversy over pricing impacting patient access to this medication. In response, the FDA released a statement in March 2011Citation15, where they noted:

“In order to support access to this important drug, at this time and under this unique situation, FDA does not intend to take enforcement action against pharmacies that compound hydroxyprogesterone caproate based on a valid prescription for an individually identified patient unless the compounded products are unsafe, of substandard quality, or are not being compounded in accordance with appropriate standards for compounding sterile products. As always, FDA may at any time revisit a decision to exercise enforcement discretion.”Citation15

KV Pharmaceutical subsequently lowered the price, expanded patients access programs and provided to FDA the results of testing compounded 17-OHPC. Eight of the 30 compounded 17-OHPC samples (27%) failed to meet potency requirements; sixteen of the samples (53%) exceeded the impurity limit set for the FDA-approved drug productCitation16.

Some providers were initially under the misimpression that the 17-OHPC medication used in the original Meis trial was compounded. It was not. To clarify the issue, Dr. Meis published a letter in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology in 2012Citation17 noting that the supplies used in the original trial were made in GMP-compliant pharmaceutical facilities, which formed the basis of the GMPs used to produce the FDA-approved formulation of 17-OHPC (Makena), and that “it would be misleading” to state that the 17-OHPC came from compounding pharmacies. ACOG and SMFM also issued a statement clarifying the drug used in the Meis trial did not come from compounding pharmaciesCitation18.

In June 2012, FDA returned to their long-standing position, in which they stated “If there is an FDA-approved drug that is medically appropriate for a patient, the FDA-approved product should be prescribed and used.”Citation19 FDA further stated:

“Compounded drugs do not undergo the same premarket review and thus lack an FDA finding of safety and efficacy and lack an FDA finding of manufacturing quality. Therefore, when an FDA-approved drug is commercially available, the FDA recommends that practitioners prescribe the FDA-approved drug rather than a compounded drug unless the prescribing practitioner has determined that a compounded product is necessary for the particular patient and would provide a significant difference for the patient as compared to the FDA-approved commercially available drug product.”Citation19

This return by FDA to their historical position limiting the use of compounded 17-OHPC preceded the tragic fungal meningitis outbreak in the Fall of 2012 caused by contaminated compounded medications that were mass produced and shipped nationally from the New England Compounding Center (NECC). In the NECC incident, 76 fatalities were documented, primarily related to preservative-free steroids for intrathecal administration, and hundreds more patients were gravely sickenedCitation20,Citation21. Included among the numerous medications that NECC produced and had to recall was compounded 17-OHPC. While there were not documented cases of meningitis or other patient harm with 17-OHPC, this incident served as a stark reminder of the importance of GMPs to ensure quality of medications.

FDA and the Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC) acted appropriately to monitor and respond to this outbreak, including recommending that any patients who received any compounded medications from the NECC be notified and monitored for symptoms, including those who received compounded 17-OHPC. Also in response, in 2013, Congress passed the Drug Quality and Security Act (DQSA), which provided expanded regulatory authority to FDA for additional oversight of compoundingCitation20.

As a result of improved access to the approved drug, as well as updated FDA, ACOG and SMFM statements, and appropriate concern about the potential risks from compounded medication, providers relied upon Makena as the standard treatment to prevent recurrent PTB. In 2018, FDA also approved the Makena Auto-Injector for subcutaneous useCitation22, which is a single-use pre-filled drug-device combination that is ready to use, obviating the need for manual manipulation of a needle and syringe. This approval was based upon the demonstration of comparable systemic drug exposure to Makena IMCitation23. Additionally, the FDA-approved 5 generic equivalents of the original IM formulation, all of which cross-referenced the safety and efficacy demonstrated with Makena. Notably, the companies that manufacture the 5 FDA-approved generics have satisfactorily demonstrated the ability to consistently produce a quality product under GMP conditions.

While there are limited clinical data comparing compounded and FDA-approved 17-OHPC formulations, Stone et al. published a retrospective cohort evaluation of data obtained from the electronic medical records of patients prescribed weekly 17-OHPC injections at an obstetric clinic between 2009 and 2015Citation24. Out of 175 patients, 56% received Makena and 44% received the compounded formulation, from two separate compounding pharmacies. Of note, one compounding pharmacy used cottonseed oil and the second pharmacy used sesame seed oil as the 17-OHPC vehicle, rather than the castor oil which is the vehicle in the FDA-approved formulations. When medications are FDA-approved, this is based on the finished dosage product, inclusive of inactive ingredients, such as diluents. While compounding pharmacists are not restricted from reformulating medications, changing an inactive ingredient in an FDA-approved medication is not permissible without first demonstrating that the safety and efficacy are unchanged. Using an alternative diluent has the potential to impact solubility, the pharmacokinetics of 17-OHPC and/or the safety profile. Stone et al. reported that adverse drug reactions (ADRs) occurred in 16 patients, all of whom received the compounded formulation (p < .001). The most common ADRs were injection-site reaction and acute coughing following 17-OHPC administration. Of patients with an ADR, 63% discontinued therapy for prevention of preterm birth or changed to an alternative therapy. The authors concluded that providers “may consider preferential use of the commercial formulation, since 21% of women receiving compounded product experienced an ADR.”Citation24

Current situation – potential return to pharmacist-compounding of 17-OHPC

A requirement of FDA approval was that the sponsor complete a new confirmatory trial for Makena for efficacy and safety. This trial, PROLONG (Progestin’s Role in Optimizing Neonatal Gestation), was initiated prior to Makena’s approval, but subsequent enrolment of patients in the U.S. into this placebo-controlled trial was hampered because the FDA-approved medication had become the standard of care. PROLONG ultimately enrolled 1,708 subjects, mostly in Europe/Ukraine/RussiaCitation25. Top-line results were released in March 2019, with the full publication in October 2019Citation25,Citation26. 17-OHPC did not demonstrate a statistically significant reduction in PTB compared with placebo (PTB <35 weeks 11.0% in 17-OHPC; 11.5% in the placebo group). As noted, the majority (77%) of women were enrolled outside of the U.S., in countries with substantially lower rates of PTB than in the U.S. As Blackwell et al. described, the unexpectedly lower rates of PTB contributed to PROLONG being underpowered, despite the large sample size. PROLONG did reaffirm the maternal and fetal safety of 17-OHPC in pregnancyCitation25. Of particular importance to clinicians is the rate of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), as some non-controlled studies have reported an association between 17-OHPC and GDMCitation27. However, in PROLONG, GDM rates were low and comparable between groups (17-OHPC: 3.1%; placebo: 3.6%)Citation25. Given the conflicting data between one positive U.S.-based study and one international study that failed to confirm the benefit, the FDA held an Advisory Committee meeting in October 2019 to evaluate in a public and transparent manner the totality of evidence. At this meeting, the key vote as to whether FDA should pursue withdrawal of Makena resulted in a split, with 9 members voting their recommendation that FDA pursue withdrawal and 7 members voting to leave Makena on the market and require additional effectiveness data be generated. Of the 16 members of the committee, 6 were obstetricians and/or MFMs; 5 of the 6 obstetricians/MFMs voted to keep Makena on the market and require additional data. Among those members voting for FDA to pursue withdrawal, many expressed their belief that because 17-OHPC was currently routinely used, the only way to enroll participants in a placebo-controlled study was if there was no FDA-approved option available (the reader is referred to pages 300–306 of the transcript of the 29 October 2019 FDA Advisory Committee meeting)Citation28. Removal of Makena from the market would also result in the generic equivalents being withdrawn. While FDA is not bound by the Advisory Committee’s recommendation, the vote and their discussion are being considered by the FDA.

There was considerable acknowledgement that if FDA-approved forms of 17-OHPC became unavailable after 17 years of clinical utilization in the U.S., providers would return to using pharmacist-compounded 17-OHPC formulationsCitation28. A key part of this discussion included the lack of other evidenced-based alternatives for women with a history of spontaneous PTB; as the FDA has acknowledged, vaginal progesterone has also been studied for this risk factor and not been shown to be effectiveCitation12,Citation29–31.

Given the potential for providers to no longer have access to FDA-approved forms of 17-OHPC, it is important to understand the differences between unapproved compounded formulations and FDA-approved medications, as well as the actions the FDA has taken since the DQSA was enacted. Additionally, understanding relevant medical society positions on prescribing compounded medications is an important consideration for providers.

Compounding post drug quality and security act (DQSA)

The FDA released a compounding progress report three years after DQSA was enactedCitation20, in which they noted that they had devoted significant resources to implementing and enforcing the DQSA in the wake of the 2012 fungal meningitis outbreak and other serious injuries and deaths due to compounding. In this report, FDA described the following, while recognizing that more work needs to be done:

“FDA continues to investigate many reports of serious adverse events associated with contaminated or otherwise poor-quality compounded drugs, including sterile and non-sterile drugs that were thousands of times stronger than labeled. FDA also has identified insanitary conditions at the majority of sterile drug compounders that it has inspected since enactment of the DQSA. Insanitary conditions can cause drugs to become contaminated and lead to serious patient injury and death. Examples of recent inspectional observations include dog beds and dog hairs in close proximity to a sterile compounding room, dead insects in ceilings, renovations made without any evidence of controls to protect sterile drugs from contamination, and use of coffee filters to filter particulates.”Citation20

FDA has provided extensive education to healthcare providers and consumers to address the differences between FDA-approved medications versus compounded drugs. Specifically, FDA-approved medications are required to undergo premarket approval to demonstrate safety and efficacy, be labeled with adequate directions for use so patients can safely use them for their intended purposes, and be manufactured according to current good manufacturing practice (CGMP) requirements, which are intended to assure the identity, potency, quality, and purity of drugs by requiring adequate control of manufacturing operationsCitation32. In addition, drug manufacturers are required to collect and share with the FDA any reports of adverse events associated with their medication.

In contrast, FDA does not verify the safety, effectiveness, or quality of compounded drugs before they are made availableCitation20. As recognized by FDA, poor compounding practices can result in serious drug quality problems, such as contamination or medications that do not possess the potency, quality, and purity they are supposed to have. FDA has consistently cautioned that compounded drugs present a higher risk than approved drugs and should be used only when the patient has a medical need that cannot be met by FDA-approved drugsCitation33.

The FDA has worked diligently with key stakeholders to balance public safety while retaining patient access to compounding for the occasions it is needed for the benefit of individual patients. In addition to holding working intergovernmental meetings with state regulators, FDA has published a number of guidance documents regarding their position. Further, as of 2017, the FDA has issued more than 130 warning letters advising compounders of significant violations of federal law, has Issued more than 30 letters referring inspectional findings to state regulatory agencies, and has overseen more than 100 recalls involving compounded drugsCitation20. Despite these efforts, the FDA stated that they have “found during follow-up inspections that many compounders continue to fail to comply with applicable requirements of the law.”Citation20

Specifically, for compounded 17-OHPC, as of August 2019 there have been 26 recalls since 2013 (). This is particularly concerning since only a fraction of the existing compounding pharmacies are inspected. The FDA has acknowledged that they do not “interact with the vast majority of the thousands of compounders” and are often only aware of potential problems after a complaint of an adverse event or visible contamination is receivedCitation20.

Table 1. Recalls of compounded 17-OHPC.

Moreover, there is a lack of adequate reporting requirements for adverse events related to compounded productsCitation34. Thus, the true extent of risk caused by the use of compounded versions of 17-OHPC cannot be known.

FDA-approved medications may also be subject to quality problems resulting in recalls. However, the magnitude by which this occurs for compounders compared with manufacturers of approved drugs is vastly different. One FDA report from 2001 noted that 34% of samples of compounded medication failed quality testing, mostly for sub-standard potency ranging from 59% to 89% of the target doseCitation35. In the same report, the FDA noted that the failure rate for 3,000 FDA-approved and regulated commercial products was <2%. No recalls of Makena or the cross-referenced FDA-approved generics have occurred to date.

Active pharmaceutical ingredient (API)

Following the 2012 meningitis outbreak, and DQSA passage, many compounding pharmacies invested substantially in improving quality systems to minimize potential harm to patients. One area that remains challenging for even the most stringent pharmacist is the sourcing of raw material, specifically the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API). For API used in the manufacture of FDA-approved medications, a drug master file (DMF) is a crucial part of the new drug application (NDA) or abbreviated new drug application (ANDA) review prior to approvalCitation36. This ensures that the API is appropriately sourced and free from contaminants; any changes to DMFs must go through re-review by FDA. No such safeguard is in place for compounding pharmacies, and a large gray-market exists in which repackagers often relabel APIs, whereby it seems the bulk substance is produced in the U.S., when the actual point of origin may be difficult if not impossible to traceCitation16.

Labeling

The Prescribing Information for any FDA-approved medication contains the data that FDA has determined is relevant for both healthcare providers and patients when considering a medication’s risks and benefits. As Makena is the Reference Listed Drug (RLD) upon which the ANDA approvals were based, the Prescribing Information for the generic 17-OHPC products reflects the current Makena Prescribing Information. Prescribing Information for Makena currently describes the safety and efficacy from the original NICHD MFMU Meis trialCitation22. The sponsor has submitted a proposed Makena labeling update to FDA to include safety and efficacy from PROLONG. If the FDA-approved versions of 17-OHPC are permitted to remain available for patients, this comprehensive safety and efficacy information from both the Meis and PROLONG trials are critical for providers and patients to consider. Importantly, no such labeling requirement to include the safety and efficacy information exists for compounded formulations.

Medical societies: compounding

The most widely prescribed compounded medications in women’s health care are those used to manage menopausal symptoms. Such compounding proliferated following the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) trial, which resulted in class labeling for all estrogen-containing medications describing the potential for increased cardiovascular and breast cancer risksCitation37. While ACOG does not have a guidance related to compounded 17-OHPC, their Committee Opinion on Compounded Bioidentical Menopausal Hormone Therapy is relevant to consider:

“Compounded preparations are not regulated by the FDA….Because of a lack of FDA oversight, most compounded preparations have not undergone any rigorous clinical testing for either safety or efficacy, the purity, potency, and quality of compounded preparations are a concern.”Citation38

Similarly, the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) has taken an active stance regarding compoundingCitation39, presumably because of the prevalence of compounding in their specialty. A 2017 NAMS Position Statement included the following:

“Compounded bioidentical HT [hormone therapy] presents safety concerns such as minimal government regulation and monitoring, overdosing or underdosing, presence of impurities or lack of sterility, lack of scientific efficacy and safety data, and lack of a label outlining risks.”Citation39

These compounded hormonal therapies for menopause are administered vaginally, topically or orally. 17-OHPC is administered parenterally, which confers additional risk with compounding.

Medical societies: 17-OHPC

Both ACOG and the Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine (SMFM) issued statements following the publication of the PROLONG trialCitation40,Citation41. ACOG notes, in part:

“ACOG is not changing our clinical recommendations at this time and continues to recommend offering hydroxyprogesterone caproate as outlined in Practice Bulletin #130, Prediction and Prevention of Preterm Birth.”Citation40

SMFM notes, in part:

“Based on the evidence of effectiveness in the Meis study, which is the trial with the largest number of U.S. patients, and given the lack of demonstrated safety concerns, SMFM believes that it is reasonable for providers to use 17-OHPC in women with a profile more representative of the very high-risk population reported in the Meis trial. For all women at risk of recurrent sPTB, the risk/benefit discussion should incorporate a shared decision-making approach, taking into account the lack of short-term safety concerns but uncertainty regarding benefit.”Citation41

If the FDA does withdraw FDA-approved forms of 17-OHPC, providers and patients will be left without access to commercially available, GMP-produced formulations, and would likely return to prescribing compounded 17-OHPC, potentially placing their patients and themselves at risk. Physicians do not have the training or experience to suitably evaluate a compounding pharmacy’s ability to maintain aseptic technique and consistency of drug concentrations, or to investigate how the pharmacy ensures the potency and purity of their active pharmaceutical ingredients and finished products.

Conclusion

The PROLONG results were unexpected for many obstetrical providers in light of prior positive studiesCitation4,Citation11. Moreover, clinicians who have relied upon 17-OHPC since 2003 have perceived a benefit based upon their own clinical experience. This real-world experience should not be discounted, particularly as there are not evidenced-based alternative medications. Additional research is needed regarding the effectiveness of 17-OHPC in the U.S. population, given the markedly higher rates of PTB in the U.S. compared with other industrialized nations. The “unintended consequence” of removal of FDA approved formulations – both brand name Makena and the generic equivalents – would be the return to administering compounded 17-OHPC, an inherently riskier therapeutic choice than the FDA-approved versions, as FDA has consistently cautioned with all compounded drugs. Given the intended use in a high-risk pregnant population, this is not an acceptable solution. It is important to recognize that FDA-approved medications are often prescribed off-label during pregnancy (e.g. steroids for fetal lung maturation and antibiotics for women with preterm premature rupture of membranes). While the specific use in pregnancy is not FDA-approved, these medications are FDA-approved for other uses. Thus, obstetricians and patients have the assurance that these “off-label” medications are GMP-produced. This is in marked contrast to compounded medications, which are not FDA approved.

It is imperative that additional research with FDA-approved, GMP-produced 17-OHPC formulations be conducted, while not depriving at-risk women of access to treatment and/or placing patients at potential harm and providers at potential liability. AMAG Pharmaceuticals, the sponsor of Makena, intends to work with FDA to find an appropriate, timely and feasible means to generate additional U.S.-based effectiveness data of 17-OHPC. Given that 17-OHPC has been widely used in the past 9 years, one possible means is utilizing real-world evidence based upon a retrospective study, which may further refine predictors of benefit. While the sponsor believes that a placebo-controlled RCT would have similar enrolment challenges with potential bias to a lower-risk population, a prospective observational study would facilitate a robust collection of data, without requiring high-risk pregnant women to receive a placebo.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

DLG and MDR did not receive funding for their work on this paper. JLG is an employee of AMAG Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the manufacturer of 17α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate (Makena).

Declaration of financial/other relationships

DLG has served on AMAG Pharmaceuticals, Inc. speakers’ bureau and participated in prior advisory boards, for which he received consulting fees. MDR has participated in prior AMAG Pharmaceuticals, Inc. advisory boards, for which he received consulting fees. JLG is an employee of AMAG Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the manufacturer of 17α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate (Makena). Peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from CMRO for their review work but have no other relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

All authors were involved in identifying the need for a paper on this topic and conceived of the paper’s content; JLG wrote the first draft, and DLG and MDR made critical revisions to the intellectual content of the paper; all authors approved the final version to be submitted to the journal, and; all authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Nancy Griffith, PhD, an employee of AMAG Pharmaceuticals, Inc., for manuscript preparation and review.

References

- Thom EA, Rice MM, Saade GR, et al. What we have learned about the design of randomized trials in pregnancy. Semin Perinatol. 2016;40(5):328–334.

- March of Dimes. 2019. March of Dimes Report Card; [cited 2020 May 21]. Available from: https://www.marchofdimes.org/mission/reportcard.aspx.

- Mercer BM, Goldenberg RL, Moawad AH, et al. The preterm prediction study: effect of gestational age and cause of preterm birth on subsequent obstetric outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181(5):1216–1221.

- Meis PJ, Klebanoff M, Thom E, et al. Prevention of recurrent preterm delivery by 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(24):2379–2385.

- Iams JD, Newman RB, Thom EA, et al. Frequency of uterine contractions and the risk of spontaneous preterm delivery. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(4):250–255.

- Iams JD. Was the preterm birth rate in the placebo group too high in the Meis MFMU Network trial of 17-OHPC? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(5):409–410.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion. Use of progesterone to reduce preterm birth. Number 291, November 2003. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2004;84:93–94.

- Da Fonseca EB, Bittar RE, Carvalho MH, et al. Prophylactic administration of progesterone by vaginal suppository to reduce the incidence of spontaneous preterm birth in women at increased risk: a randomized placebo-controlled double-blind study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(2):419–424.

- Ness A, Dias T, Damus K, et al. Impact of the recent randomized trials on the use of progesterone to prevent preterm birth: a 2005 follow-up survey. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(4):1174–1179.

- Henderson ZT, Power ML, Berghella V, et al. Attitudes and practices regarding use of progesterone to prevent preterm births. Am J Perinatol. 2009;26(7):529–536.

- Keirse MJ. Progestogen administration in pregnancy may prevent preterm delivery. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1990;97(2):149–154.

- Division of Bone, Reproductive, and Urologic Products. Office of New Drugs, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Food and Drug Administration. Bone, Reproductive, and Urologic Drugs Advisory Committee (BRUDAC) Meeting October 29, 2019. FDA Briefing Document NDA 021945. Hydroxyprogesterone Caproate Injection (trade name Makena). October 2019; [cited 2020 Mar 27]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/132003/download.

- Division of Bone, Reproductive, and Urologic Products. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Medical Review: Application number 21945Orig1s000. February 2011; [cited 2020 Mar 29]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2011/021945Orig1s000MedR.pdf.

- Sellers S, Utian WH. Pharmacy compounding primer for physicians. Prescriber beware. Drugs. 2012;72(16):2043– 2050.

- United States Food and Drug Administration. FDA statement on Makena. March 30, 2011; [cited 2020 Mar 29]. Available from: https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20170113192840/. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm249025.htm.

- Chollet JL, Jozwiakowski MJ. Quality investigation of hydroxyprogesterone caproate active pharmaceutical ingredient and injection. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2012;38(5):540–549.

- Meis PJ. The source of 17P used in NICHD trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(5):e11.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Information update on 17a-hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17P) from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. October 13, 2011.

- United States Food and Drug Administration. Questions and answers on updated FDA statement on compounded versions of hydroxyprogesterone caproate (the active ingredient in Makena). June 2012; [cited 2020 Mar 29]. Available from: https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20170113105722/http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm310215.htm.

- United States Food and Drug Administration. FDA’s human drug compounding progress report: Three years after enactment of the Drug Quality and Security Act. January 2017; [cited 2020 Mar 27]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/human-drug-compounding/fdas-human-drug-compounding-progress-report-three-years-after-enactment-drug-quality-and-security.

- Raymond N. US prosecutors seek 35 years in prison for meningitis outbreak exec. June 23, 2017; [cited 2020 Mar 27]. Available from: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-massachusetts-meningitis-idUSKBN19E1GR.

- MAKENA® (hydroxyprogesterone caproate injection) for intramuscular use [package insert]. Waltham (MA): Amag Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2018.

- Krop J, Kramer WG. Comparative bioavailability of hydroxyprogesterone caproate administered via intramuscular injection or subcutaneous autoinjector in healthy postmenopausal women: a randomized, parallel group, open-label study. Clin Ther. 2017;39(12):2345–2354.

- Stone RH, Bobowski C, Milikhiker N, et al. Prevention of preterm labor with 17α-hydroxyprogesterone (17OHP) caproate: a comparison of adverse drug reaction rates between compounded and commercial formulations. Am J Perinatol. 2017;34(14):1436–1441.

- Blackwell SC, Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Biggio JR, Jr, et al. 17-OHPC to prevent recurrent preterm birth in singleton gestations (PROLONG Study): a multicenter, international, randomized double-blind trial. Am J Perinatol. 2020;37(02):127–136.

- Amag Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Amag Pharmaceuticals announces topline results from the PROLONG trial evaluating MAKENA® (hydroxyprogesterone caproate injection). March 8, 2019; [cited 2020 May 20]. Available from: https://www.amagpharma.com/news/amag-pharmaceuticals-announces-topline-results-from-the-prolong-trial-evaluating-makena-hydroxyprogesterone-caproate-injection/.

- Eke AC, Sheffield J, Graham EM. 17a-hydroxyprogesterone caproate and the risk of glucose intolerance in pregnancy. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133(3):468–475.

- Division of Bone, Reproductive, and Urologic Products. Office of New Drugs, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Food and Drug Administration. Bone, Reproductive, and Urologic Drugs Advisory Committee (BRUDAC). Transcript for the October 29, 2019 Meeting of the Bone, Reproductive and Urologic Drugs Advisory Committee (BRUDAC). October 2019; [cited 2020 May 21]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/136108/download.

- O'Brien JM, Adair CD, Lewis DF, et al. Progesterone vaginal gel for the reduction of recurrent preterm birth: primary results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;30(5):687–696.

- Norman JE, Marlow N, Messow C-M, et al. Vaginal progesterone prophylaxis for preterm birth (the OPPTIMUM study): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10033):2106–2116.

- Crowther CA, Ashwood P, McPhee AJ, et al. Vaginal progesterone pessaries for pregnant women with a previous preterm birth to prevent neonatal respiratory distress syndrome (the PROGRESS study): a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2017;14(9):e1002390.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Food and Drug Administration. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Centers for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER). Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM). Office of Regulatory Affairs (ORA). Guidance for industry. Quality systems approach to pharmaceutical current good manufacturing practice regulations. September 2006; [cited 2020 Mar 27]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/quality-systems-approach-pharmaceutical-current-good-manufacturing-practice-regulations.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Food and Drug Administration. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Office of Compliance/OUDLC. Guidance for industry. Compounding drug products that are essentially copies of approved drugs under section 503B of the Federal, Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. January 2018; [cited 2020 Apr 14]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/compounded-drug-products-are-essentially-copies-approved-drug-products-under-section-503b-federal.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts. U.S. Illnesses and deaths associated with compounded or repackaged medications, 2001-19. March 2020; [cited 2020 Apr 14]. Available from: https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/data-visualizations/2020/us-illnesses-and-deaths-associated-with-compounded-or-repackaged-medications-2001-19.

- United States Food and Drug Administration. Limited FDA Survey of Compounded Drug Products. 2001; [cited 2020 Mar 29]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/human-drug-compounding/report-limited-fda-survey-compounded-drug-products.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Food and Drug Administration. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Centers for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER). Guidance for industry. Drug master files (draft guidance). October 2019; [cited 2020 Mar 29]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/drug-master-files-guidance-industry.

- Simon JA. The Woman’s Health Initiative and one of many unintended consequences. Menopause. 2016;23(10):1057–1059.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee on Gynecologic Practice and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine Practice Committee. Compounded bioidentical menopausal hormone therapy. Committee opinion number 532. August 2012; [cited 2020 Mar 29]. Available from: https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2012/08/compounded-bioidentical-menopausal-hormone-therapy.

- North American Menopause Society. The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2017;24(7):728–753.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG statement on 17P hydroxyprogestrone caproate. October 2019; [cited 2020 Mar 29]. Available from: https://www.acog.org/news/news-releases/2019/10/acog-statement-on-17p-hydroxyprogesterone-caproate.

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Publications Committee. SMFM Statement: Use of 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate for prevention of recurrent preterm birth. October 2019; [cited 2020 Mar 29]. Available from: https://els-jbs-prod-cdn.literatumonline.com/pb/assets/raw/Health%20Advance/journals/ymob/SMFM_Statement_PROLONG-1572023839767.pdf.