Abstract

Objectives

High treatment satisfaction in both patients and physicians is an important factor in improving quality of life in psoriasis patients. This study aimed to evaluate treatment satisfaction alignment between psoriasis patients and physicians and to identify factors associated with satisfaction misalignment, especially “physician-predominant” misalignment.

Methods

This is a nationwide multicenter cross-sectional study. Subjects were paired moderate to severe psoriasis outpatients and their physicians. Treatment satisfaction was evaluated on a scale from 0 to 10. Subjects were defined as “misaligned” when the difference in treatment satisfaction was over ±1 between the patient–physician pair.

Results

A total of 425 pairs were collected from 54 facilities in Japan. The mean patient age and disease duration were 56.5 years and 18.7 years, respectively. The mean physician age was 50.6 years and 69.6% of physicians specialized in psoriasis. Treatment satisfaction misalignment was found in 49.9% of the patient–physician pairs. Among misaligned pairs, 43.6% were “physician-predominant” pairs. In the multivariate logistic regression analyses, “treatment is effective” was the most important reason for treatment satisfaction (odds ratio [OR]: 35.5; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 5.43, 231.78). Symptoms in the genital area (OR: 10.2; 95% CI: 2.55, 40.93) and lack of understanding of treatment options by patients (OR: 7.5; 95% CI: 2.19, 25.94) were key factors leading to “physician-predominant” status.

Conclusions

The results suggest that genital psoriasis plays an important role in treatment satisfaction from the patient perspective, and illustrate the importance of communication between patients and physicians which potentially resolves these factors and improves misalignment.

Introduction

The prevalence of psoriasis in Japan is approximately 0.3%Citation1, which is lower than that in Europe (2–4%) and the United StatesCitation2–4. The number of psoriasis patients in Japan was estimated to be 500,000–600,000 people in 2010Citation1. Based on the proportion of the affected area relative to the total body surface area (BSA), the severity of psoriasis is rated on a three-grade scale (mild, moderate or severe). Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) scores, and static Physician Global Assessment (sPGA) are the most frequently employed clinical tools to evaluate the severity of this disease.

Psoriasis symptoms often influence not only physical function but also mental and social functions of patients, resulting in a decrease in quality of life (QOL). Correlations between severity rating by PASI and a psoriasis-specific QOL scale (Psoriasis Disability Index, Skindex-16) and Short Form 36 (SF-36, a comprehensive health-associated QOL scale) have been found in JapanCitation5–7. Lanna et al. reported itching as a possible mediating factorCitation8. Thus, an improvement of PASI results in an improvement of QOL.

Treatment satisfaction may be another important factor for QOL. Torii and NakagawaCitation9 conducted a survey on treatment satisfaction with psoriasis patients and their treating physicians. They reported that biologic users had the highest patients’ treatment satisfaction in all treatments (topical, oral). However, 27.8% of overall patients reported that they were not satisfied with their treatment, while their physicians reported high satisfaction. The misalignment of treatment satisfaction between patients and physicians arises more often in groups with a high Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), and high DLQI scores are associated with lower QOL.

Improvement of PASI and taking into account mental and social functions leads to high treatment satisfaction of patients and high QOL. On the other hand, several studies reported misalignments in the perception of symptoms, severity and treatment satisfaction between psoriasis patients and physiciansCitation9–12; however, it is not clear which factors contributed to treatment satisfaction misalignment between patients and their treating physicians. Thus, treatment satisfaction misalignment rather than alignment, especially “physician-predominant” satisfaction misalignment among misaligned pairs was focused on in this study. The improvement of factors associated with the misalignment may lead to better treatment strategies in the clinical setting.

In our previous study, a multicenter cross-sectional study was conducted to assess treatment goal misalignment between psoriasis patients and their physicians, and identify factors that contributed to treatment goal misalignmentCitation13. This study was a secondary analysis of this data.

The aim of this study was to evaluate treatment satisfaction misalignment between paired psoriasis patients and their treating physicians, and to identify factors associated with satisfaction misalignment.

Methods

Study design

This study was a nationwide multicenter cross-sectional observational study. Subjects were physician-reported moderate to severe psoriasis outpatients with a history of systemic treatments, including biologicals, and their treating physicians. Details of the study design were previously reportedCitation13. This study was performed in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices (GPPs), the Ethical Guidelines Concerning Medical Studies in Human Subjects and the ethical principles based on the relevant statutes/standards in the country concerned. It was reviewed and approved in advance by the Ethics Committee of Jichi Medical University, the Central IRB of Medical Corporation Ganka-Koseikai (Central IRB) and the Ethics Committees organized as needed at each participating hospital.

Each patient and their treating physician completed the survey (paper-based questionnaire) independently. To avoid selection bias by physicians, patients were selected randomly and enrolled consecutively. There was no restriction with background treatment for psoriasis. The survey consisted of 52 questions for patients and 31 questions for physicians. The questions were categorized into: (1) background variables of patients and physicians (sex, age, treatment in past 2–3 weeks, lifestyle), (2) disease severity, (3) treatment goals, and (4) treatment satisfaction and QOL (). Disease severity was evaluated by patient global assessment (patients’ GA) or physician global assessment (physicians’ GA) (scale from 0–5; a higher score means greater severity). Affected sites and BSA were also evaluated in the patients. Treatment satisfaction was evaluated using a scale from 0 to 10 in the questionnaire and primary endpoint in this analysis. The Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM) was also used as another scale to evaluate treatment satisfaction. QOL was assessed by DLQI.

Treatment satisfaction was evaluated using a scale from 0 to 10 (0 representing the lowest satisfaction, 10 representing the highest satisfaction, both patients and physicians answered the same questions). Subjects were defined as “treatment satisfaction aligned” when the difference in treatment satisfaction was within ±1 between the patient–physician pair, and “treatment satisfaction misaligned” when the difference was over 1. In treatment satisfaction misaligned pairs, when physicians’ satisfaction was rated at least 2 points higher than that of patients, they were grouped as “physician predominant,” and inverse cases were grouped as “patient predominant.” The survey was conducted between October 2015 and May 2016.

Statistical analysis

Logistic regression analysis by dichotomy of “physician predominant” (denoted as 1) and “patient predominant” (denoted as 0) in the patient–physician pairs was applied. Analyses were conducted by a three-step process. Step 1: distributions of 131 variables from the questionnaire were statistically compared between the “physician-predominant” and the “patient-predominant” groups. This was an exploratory analysis. Variables with a p value less than .25 were selected. Step 2: variables selected in Step 1 were checked for co-linearity and clinical validity was discussed. Step 3: variables selected in Step 2 were put into a logistic regression model and the stepwise method (the significance level of model entry and stay were p < .05) was used to find optimal variables.

For categorical variables, the chi-squared test was applied to test for differences. For continuous variables, normality was evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk test. If normality was rejected, the Wilcoxon rank sum test was employed and, if not rejected, the t-test was applied to test for differences. All statistical analyses were performed on SAS ver. 9.4. (SAS Institute, Cary, NC); p < .05 was regarded as significant.

Results

Study population

A total of 449 patient–physician pairs from 54 facilities were registered and answers were collected from 425 pairs (response rate, 94.7%). Demographic and background characteristics for patients (n = 425) and physicians (n = 70) are shown in . The patients were 56.5 years old on average and were mostly men (74.6%). The mean disease duration was 18.7 years, and the most frequent affected site/location of psoriasis was the leg (78.1%). The mean age of physicians was 50.6 years and the majority were men (64.3%). Of all physicians, 86.8% had 10 years or longer experience in treating psoriasis patients. The mean score of severity for physicians’ GA was 2.51 while patients’ GA was 2.55.

Table 1. Characteristics of subjects.

Treatment satisfaction

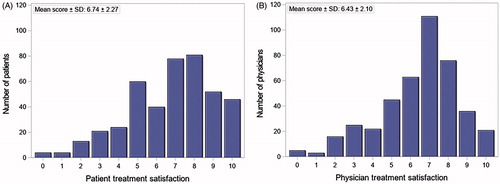

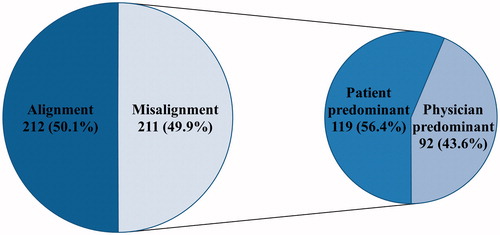

Two pairs were excluded for having no answer about treatment satisfaction, and a total of 423 pairs were included in the analyses. The mean scores for TSQM (0–100 scale) for effectiveness, side effects, convenience and global satisfaction were 59.71, 92.88, 59.84 and 59.69, respectively. The mean scores for treatment satisfaction (0–10 scale) were 6.74 for patients and 6.43 for physicians (). The distribution of treatment satisfaction was bimodal (peaks were 5 and 7–8) in patients, while 7 was the most frequent score in physicians. Patient–physician treatment satisfaction misalignment was found in 49.9% of the pairs. Among them (n = 211), about 43.6% of pairs were grouped as “physician predominant”, meaning that physicians had higher satisfaction of 2 or more than the patients () .

Figure 1. Distribution of patients’ (A, N = 423) and physicians’ (B, N = 423) treatment satisfaction. (A) Patients. (B) Physicians. Abbreviation. SD, Standard deviation.

Figure 2. Treatment satisfaction misalignment. Alignment, The difference of treatment satisfaction was within ±1 between the patient–physician pair; Misalignment, The absolute difference of treatment satisfaction was over 1 between the patient–physician pair; Patient predominant, Patients’ treatment satisfaction was at least 2 points higher than physicians’; Physician predominant, Physicians’ treatment satisfaction was at least 2 points higher than patients’.

Comparison between “physician-predominant” and “patient-predominant” groups

Comparison of the “physician-predominant” and “patient-predominant” groups () showed that the “physician-predominant” group had more patients who had symptoms in their genital areas (p = .002, answers from “2 Severity evaluation – Affected site” []), and fewer patients who received phototherapy (p = .043, answers from “1 Patient background – Treatment in the past 2–3 weeks”). The proportion of topical drugs only was 14.1% in the “physician-predominant” group and 17.7% in the “patient-predominant” group; there was no significant difference (p = .491). For other background treatment in the past 2–3 weeks, the proportions receiving topical drugs, oral drugs and biologics in the “physician-predominant” group were 81.5%, 52.2% and 20.7%, respectively. On the other hand, the proportions receiving these treatments in the “patient-predominant” group were 92.4%, 50.4% and 17.7%, respectively. Physicians were mostly male (p = .032, answers from “1 Physician background – Sex”) and the severity ratings by physicians’ GA were lower in the “physician predominant” group (p = .002, answers from “2 Severity evaluation – Severity rating (Physician GA)”).

Table 2. Patient characteristics in “physician-predominant” and “patient-predominant” groups (statistically significant variables).

Evaluation of factors affecting “physician-predominant” treatment satisfaction misalignment

Among 131 variables, 58 variables were selected in Step 1. Of these 58 variables, 6 variables were excluded taking into account multicollinearity and clinical validity in Step 2. The remaining 52 variables were applied in a logistic regression model, and 8 variables were selected by the stepwise method. The results demonstrated that “treatment is effective” was the most important reason for treatment satisfaction (odds ratio [OR]: 35.5; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 5.43, 231.78) and it was the strongest factor in the physicians. Symptoms in the genital area (OR: 10.2; 95% CI: 2.55, 40.93) and lack of understanding of treatment options by patients (OR: 7.5; 95% CI: 2.19, 25.94) were key factors leading to “physician-predominant” treatment satisfaction misalignment. On the other hand, receiving phototherapy, no change of treatment goal setting from start of treatment, high TSQM effectiveness score, sex of physician (female) and high physicians’ GA score were suggested as factors associated with “patient-predominant” satisfaction ().

Table 3. Factors associated with “physician-predominant” treatment satisfaction.

Patients receiving phototherapy visited their physicians more frequently (3.15 ± 2.18 times/month vs. 1.40 ± 1.03 times/month, p < .0001). The proportion of “patient-predominant” satisfaction was higher in female physicians and their patient pairs than in male physicians’ pairs (42/62 [67.7%] vs. 77/149 [51.7%], p = .032). Patients who use biologics had higher treatment satisfaction for effectiveness than non-users (TSQM effectiveness score 69.58 ± 21.06 vs. 53.01 ± 17.09, p < .0001).

Discussion

This study revealed that 49.9% of psoriasis patient–physician pairs had a misalignment in their treatment satisfaction. Among misaligned pairs, 44% were “physician-predominant” treatment satisfaction misalignment pairs; therefore, patients had lower satisfaction than physicians. In the physicians “treatment is effective” was the most important reason for treatment satisfaction. Symptoms in the genital area and lack of understanding on treatment options by patients were shown to be factors strongly leading to “physician predominant” treatment satisfaction misalignment.

According to the study in Japan by Torii and Nakagawa, 27.8% of psoriasis patient–physician pairs had a discrepancy in their satisfaction with their treatmentCitation9. In a cross-sectional study in nine countries, discrepancies on satisfaction with overall disease control were found in 61% pairs of psoriasis patients and physiciansCitation12 and 66% pairs of patients and physicians in RussiaCitation11. However, the proportion of misalignment may vary due to the difference in evaluation methods, definition of misalignment and healthcare environment where the study was conducted.

In this study, having symptoms in the genital area was one of the factors leading to “physician predominant” satisfaction misalignment. Similar results were obtained by Torii and Nakagawa who found that patients with symptoms in the “hips or genital areas”, “hands or fingers” and “legs or feet” had lower treatment satisfactionCitation9. Callis Duffin et al. conducted a survey to achieve international consensus among psoriasis stakeholders on the core domains that should be measured in psoriasis clinical trials. Genital psoriasis was selected as one of the core domains in the patient group; however, it was not selected by health care professionalsCitation14. These results suggest that genital psoriasis plays an important role in treatment satisfaction, because physicians are possibly not aware of the symptom in the genital area. In this study, patients’ GA was much higher than physicians’ GA in patients who had symptoms in the genital area. The average difference (patients’ GA − physicians’ GA) was 0.384 (p = .023) in patients who had symptoms in the genital area compared with −0.020 (p = .782) in those who did not have these symptoms.

Receiving phototherapy was revealed to be a factor leading to “patient-predominant” satisfaction misalignment. As patients receiving phototherapy need to visit a physician regularly, it may result in high treatment satisfaction due to more frequent visits, which leads to greater interaction and better communication with the physician. However, it is difficult for working patients to visit a physician frequently. Thus, working status may be a confounding factor for treatment satisfaction.

An analysis using a random sample of Medicare beneficiaries revealed that patients treated by female physicians had a significantly higher treatment outcomeCitation15. In this study, the proportion of “patient predominant” satisfaction misalignment was higher in female physicians and their patients.

In the previous study, misalignment in treatment goal setting between psoriasis patients and their physicians was evaluated. The treatment expectation of “complete clearance” by patients and lack of understanding of treatment options were two significant contributing factors to treatment goal misalignmentCitation13. In this study, it was found that a lack of understanding of treatment options by patients, that is an important element in achieving shared decision makingCitation16, was a key factor for misalignment in treatment satisfaction. In 2010, biologics were approved in Japan for treating psoriasis and treatment options have increased with advances in technology (topical, oral, biologics, phototherapy). Biologic users had a high TSQM effectiveness score in this study; however, each treatment has both benefits and risks. In general, since psoriasis treatment must take into account many components, such as treatment efficacy, side effects, cost of treatment and QOL, correct understanding and selecting optimal treatment must be important factors for both treatment goal setting and satisfaction. Physicians should monitor patients’ needs even after psoriasis symptoms improve.

This study has several limitations. First, although patients were selected by adopting the consecutive enrollment method, selection bias could not be completely eliminated. Second, as this study was a cross-sectional study, the causal relationships between “physician-predominant” treatment satisfaction misalignment and the factors associated with it could not be clarified; however, the results of this study were generally consistent with previous reports.

Conclusion

This study found misalignments in treatment satisfaction between psoriasis patients and their physicians in a clinical setting in Japan. Symptoms in the genital area and lack of understanding of treatment options by patients were important factors that led to “physician-predominant” satisfaction misalignment. On the other hand, receiving phototherapy, which makes patients visit their physician frequently, was a factor leading to “patient-predominant” satisfaction misalignment. Communication between patients and physicians potentially resolves these factors. This study may provide some evidence towards optimal treatment selection in which both patients and physician are satisfied with their treatment.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This work was supported by Eli Lilly Japan.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

Y.O. has disclosed that she has been a consultant, scientific advisor and/or investigator for Eli Lilly KK, Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co. Ltd, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Maruho Co. Ltd, Celgene KK, Janssen Pharmaceutical KK, AbbVie GK, Eisai Co. Ltd, Torii Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Leo Pharma A/S, MSD KK, Boehringer Ingelheim Japan Inc., Novartis AG, Taiho Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd and Bristol-Myers Squibb Company. H.T.-I., T.H. and T.A. have disclosed that they are employees of Eli Lilly Japan KK. S.I. has disclosed that she is an employee of Crecon Medical Assessment Inc. Crecon Medical Assessment Inc. was paid to conduct analyses for this manuscript. M.O. has disclosed that he has been paid as a consultant to AbbVie GK, Boehringer-Ingelheim Japan Inc., Celgene KK, Eisai Co. Ltd, Janssen Pharmaceutical KK, Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co. Ltd, LEO Pharma A/S, Eli Lilly and Company, Maruho Co. Ltd, Novartis AG, Pfizer Inc., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Torii Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd and Taiho Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed. CMRO peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the patients and physicians from the clinics and hospitals (), who generously shared their time for this study.

References

- Kubota K, Kamijima Y, Sato T, et al. Epidemiology of psoriasis and palmoplantar pustulosis: a nationwide study using the Japanese national claims database. BMJ Open. 2015;5(1):e006450–e006450.

- Gelfand JM, Weinstein R, Porter SB, et al. Prevalence and treatment of psoriasis in the United Kingdom: a population-based study. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141(12):1537–1541.

- Kurd SK, Gelfand JM. The prevalence of previously diagnosed and undiagnosed psoriasis in US adults: results from NHANES 2003–2004. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(2):218–224.

- Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, et al. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133(2):377–385.

- Hirabe M, Hasegawa T, Fujishiro Y, et al. Factors associated with quality of life among patients with psoriasis. Comparison between psoriasis-specific QOL measures and generic QOL measures. Jpn J Public Health. 2008;55(2):65–74.

- Okubo Y, Natsume S, Usui K, et al. Low-dose, short-term ciclosporin (Neoral) therapy is effective in improving patients’ quality of life as assessed by Skindex-16 and GHQ-28 in mild to severe psoriasis patients. J Dermatol. 2011;38(5):465–472.

- Okubo Y, Arai K, Fujiwara S, et al. Assessment of the quality of life of patients with psoriasis using Skindex-16 and GHQ-28. Jpn J Dermatol. 2007;117(14):2495–2505.

- Lanna C, Galluzzi C, Zangrilli A, et al. Psoriasis in difficult to treat areas: treatment role in improving health-related quality of life and perception of the disease stigma. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020. DOI:10.1080/09546634.2020.1770175

- Torii H, Nakagawa H. Questionnaire survey of perceived satisfaction with treatment of patients with psoriasis. Jpn J Dermatol. 2013;123(10):1935–1944.

- Furst DE, Tran M, Sullivan E, et al. Misalignment between physicians and patient satisfaction with psoriatic arthritis disease control. Clin Rheumatol. 2017;36(9):2045–2054.

- Kubanov AA, Bakulev AL, Fitileva TV, et al. Disease burden and treatment patterns of psoriasis in Russia: a real-world patient and dermatologist survey. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2018;8(4):581–592.

- Griffiths CEM, Augustin M, Naldi L, et al. Patient–dermatologist agreement in psoriasis severity, symptoms and satisfaction: results from a real-world multinational survey. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(9):1523–1529.

- Okubo Y, Tsuruta D, Tang AC, et al. Analysis of treatment goal alignment between Japanese psoriasis patients and their paired treating physicians. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(4):606–614.

- Callis Duffin K, Merola JF, Christensen R, et al. Identifying a core domain set to assess psoriasis in clinical trials. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(10):1137–1144.

- Tsugawa Y, Jena AB, Figueroa JF, et al. Comparison of hospital mortality and readmission rates for Medicare patients treated by male vs female physicians. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):206–213.

- Hoffmann TC, Montori VM, Del Mar C. The connection between evidence-based medicine and shared decision making. JAMA. 2014;312(13):1295–1296.

Appendix 1. Major items included in the questionnaires of patients and physicians.

Appendix 2. List of participating institutions.