Abstract

Objective

To determine the longitudinal societal costs and burden of community-dwelling patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and their caregivers in Japan.

Methods

GERAS-J was an 18-month, prospective, longitudinal, observational study. Using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), patients routinely visiting memory clinics were stratified into groups based on AD severity at baseline (mild, moderate, and moderately severe/severe [MS/S]). Healthcare resource utilization and caregiver burden were assessed using the Resource Utilization in Dementia and Zarit “Caregiver” Burden Interview questionnaires, respectively. Total monthly societal costs were estimated using Japan-specific unit costs of services and products (patient direct healthcare use, patient social care use, and informal caregiving time).

Results

Overall, 553 patients (156 mild; 209 moderate; 188 MS/S) were enrolled. MMSE scores declined (1.73, 1.38, and 0.95 points for the mild, moderate, and MS/S AD groups, respectively) and caregiver burden and resource utilization increased over 18 months in each of the AD severity groups. Cumulative total societal costs per patient over 18 months were 3.1, 3.8, and 5.3 million Japanese yen (29,006, 35,662, and 49,725 USD) for mild, moderate, and MS/S AD, respectively. Both patient social care costs and caregiver informal care costs increased with baseline disease severity, with >50% of total costs due to caregiver informal care in each disease severity subgroup.

Conclusions

Total treatment costs increased with AD severity over 18 months due to increases in both patient social care costs and caregiver informal care costs. Our data suggest current social care services in Japan are insufficient to alleviate the negative impact of AD on caregiver burden.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a chronic neurodegenerative disorder that results in progressive dementia, including loss of cognitive abilities and impairment of functional and behavioral abilities. Currently, over 50 million people worldwide are living with dementia, including an estimated 5–8% of the global population aged 60 years and overCitation1. Patients with dementia need increasing levels of care as the disease progresses. As such, dementia places a considerable burden on both patients and caregivers, and worsening dementia and behavioral disturbances in patients have been associated with increased caregiver burdenCitation2–5. The current annual cost of dementia globally is estimated at US $1 trillion, with the majority of costs borne by familiesCitation6.

In Japan, the prevalence of dementia in 2013 was 15.8% among adults aged 65 years and over, with AD representing over two-thirds of casesCitation7. With a rapidly aging population, the rate of AD is increasing in Japan, resulting in a growing burden on societyCitation8–10. In 2014, the estimated costs per patient were 5.95 million Japanese yen (JPY), and the estimated total societal cost for dementia was 14.5 trillion JPY, including 6.16 trillion JPY attributed to the costs of informal careCitation11. Total societal costs for dementia are projected to rise to 24.3 trillion JPY by 2060Citation11; however, longitudinal data are scarce.

To obtain a more accurate estimate of the societal burden of the disease over its course, comprehensive longitudinal data are necessary, with particular consideration of country-specific resource use and associated costs. Such long-term data on patient and caregiver burden in AD are limited in Japan. The GERAS-J study assessed the costs and burden of AD on community-dwelling patients and their caregivers in Japan over 18 months. Clinical and health outcomes, costs, and resource utilization were examined by baseline disease severity to gain insights into the impact of AD on 18-month outcomes.

Methods

Study design

GERAS-J was a prospective, multicenter, observational cohort study of the routine care of patients with AD in Japan with an 18-month follow-up periodCitation12. Community-dwelling patients and their primary caregivers providing unpaid informal care were enrolled from November 2016 to December 2017. Detailed study design and methods have previously been publishedCitation12. The 30 sites in the GERAS-J study included a variety of memory clinic settings (5 clinics, 12 hospitals, and 13 university hospitals) in different regions of Japan, where patients are routinely seen for diagnosis and follow-up for dementia due to AD.

Patients

Eligible patients were males and females aged ≥55 years old, who had received a diagnosis of probable AD according to the National Institute on Aging and Alzheimer’s AssociationCitation13 and with a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)Citation14 score of 26 or less. The patients were being treated at outpatient memory clinics that routinely treat patients with ADCitation12. At study entry, patients were classified into groups of mild, moderate, and moderately severe/severe [MS/S] according to AD severity at baseline using MMSECitation14 score. These criteria are consistent with the GERAS-I and United Kingdom National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines: mild, MMSE 21–26 points; moderate, MMSE 15–20 points; and moderately severe/severe, MMSE ≤14 pointsCitation15,Citation16. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices, and the Japanese Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects. The protocol was reviewed by a central ethical review board, with site-specific ethics approval as required. Patients (or their representatives) and primary caregivers provided written, informed consent for the collection and release of personal health information.

Outcome measurements

Demographic and clinical details of patients and caregivers were collected by study personnel at baseline. Outcome data were collected during routine visits at baseline and then every six months. Health outcome and resource utilization measures included the Resource Utilization in Dementia (RUD)Citation17 and Zarit “Caregiver” Burden Interview (ZBI)Citation18 questionnaires. The RUD was administered via researcher-led interviews to assess formal and informal healthcare resource utilization of patients (including accommodation) and the indirect costs to their caregivers (caregiving time, including time spent assisting patients with basic and instrumental activities of daily living [ADLs] and providing supervision). The ZBI was self-administered by caregivers to assess caregiver burdenCitation18. Clinical outcome data were gathered by researchers via interviews using the Japanese versions of validated instruments of the MMSE to assess cognitive function in patientsCitation14 and the AD Cooperative Study (ADCS) ADL InventoryCitation19 and the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI)-12Citation20 to assess patient functional ability and behavior, respectively, as reported by the caregiver.

Cost estimation

Cost estimation methods have been previously publishedCitation12. Briefly, patient and caregiver mean costs, stratified by disease severity, were estimated at each time point over 18 months based on available RUD resource use information and additional data collected on treatments, including pharmacotherapy and neuropsychological assessments, with resource-use costs taken from Japan-specific references. Three components were examined: (1) patient healthcare costs (patient medical costs, including medications, hospital admissions, emergency room visits, outpatient visits); (2) patient social care costs (other patient costs, including community care services, structural adaptations of patient living accommodation, consumables); and (3) caregiver informal care costs (costs of caregiver time and missing work). The exchange rate used to convert JPY to USD was 0.0093572, as this was the rate as of 6 April 2018Citation21.

Statistical analyses

To test for differences in outcomes between AD severity subgroups, for continuous variables, analysis of variance (followed by pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction, as indicated) or the Brown-Mood median test (exact p-value from the Monte Carlo estimate) was used; for categorical variables, Fisher’s exact test or the Monte Carlo estimate was used. A mixed model repeated measures (MMRM), with an unstructured covariance matrix, was used to assess changes from baseline to 18 months in selected outcomes (MMSE, NPI-12, ZBI). For the MMRM, all covariates were as recorded at baseline. If a continuous covariate was missing at baseline, the population median was imputed. If a categorical covariate was missing at baseline, the population mode was imputed. For the costing analysis, missing data at 18 months were not imputed for the main analyses, but sensitivity analyses of total societal costs were performed which applied multiple imputation, using the regression method to impute missing values with a monotone missing pattern. As previously detailedCitation12, the distribution of cost data was assessed for each disease severity subgroup separately. Mean costs are reported with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), which were calculated using a bootstrapping approach (lower CI from 2.5-centile; upper CI from 97.5-centile). The bootstrap resampling of the original data was performed 10,000 times, with median and mean calculated for each of the 10,000 samples. Tests of significance were based at the 5% level. Analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patient disposition

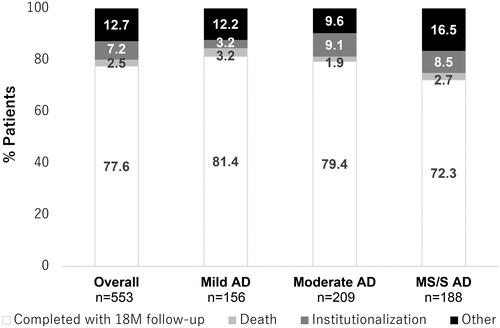

Of the total enrolled patients (N = 553), 28.2%, 37.8%, and 34.0% had mild, moderate, and MS/S AD at baseline, respectively (). Overall, 77.6% of patients completed 18 months of follow-up, with 2.5% dying, 7.2% becoming institutionalized, and a further 12.7% discontinuing for other reasons (), the majority of whom were lost to follow-up (7.6%). A lower proportion of patients with MS/S AD completed 18 months of follow-up (72.3%) compared with patients with mild (81.4%) or moderate AD (79.4%). The proportions of patients dying prior to 18 months were low and similar across groups (1.9–3.2%), but institutionalizations were higher in patients with moderate and MS/S AD compared with patients with mild AD (). In addition, “other” discontinuations (e.g. lost to follow-up) were higher in patients with MS/S AD.

Figure 1. Patient disposition at 18 months according to baseline AD severity group. “Other” refers to other reasons for discontinuation, which included lost to follow-up, patient decision, physician decision, patient entered clinical trial, and protocol-required discontinuation. Abbreviations. 18M, 18 months; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; MS/S, moderately severe/severe; n, number in group.

Baseline characteristics

Baseline demographic data for GERAS-J have been published in detailCitation12. Briefly, the majority of patients were females (72.7%) living in their own home (98.7%), with a median age of 80.3 years (). The majority of caregivers were female (70.7%) and a child of the patient (49%), with a median age of 62.1 years. Baseline characteristics of both patients and caregivers were similar across the disease severity categories except for the percentage of patients living alone (23.1%, 16.3%, and 2.7% for mild, moderate, and MS/S AD subgroups, respectively; p < .001) and, correspondingly, the percentage of caregivers living with their patients (67.9%, 73.2%, and 94.1% for mild, moderate, and MS/S AD subgroups, respectively; p < .001; ).

Table 1. Patient and caregiver demographic characteristics at baseline.

Severity level transitions

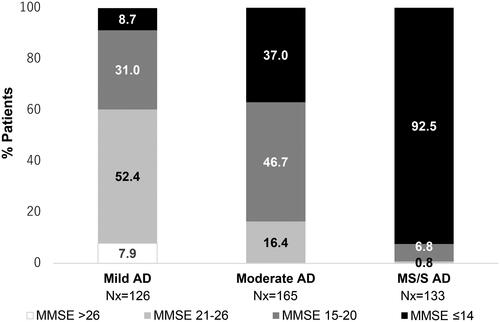

A total of 424 patients reported MMSE at 18 months, with 30.4% of patients showing a decline in MMSE scores from baseline. For patients with mild AD at baseline, 52.4% showed no change in disease severity whereas 31.0% transitioned to moderate AD, 8.7% to MS/S AD, and 7.9% improved to no impairment at 18 months (). For those with moderate AD at baseline, approximately half (47.9%) showed a decline and 9.1% showed improvement in AD severity. Of patients with MS/S AD at baseline, 92.5% showed no change in AD severity over 18 months and 7.5% had improvement ().

Figure 2. AD status (MMSE score) at 18 months stratified according to baseline AD severity group. Percentages are based on the number of patients who completed a MMSE assessment at the 18-month visit, had died, or were institutionalized before or at the 18-month visit. Indicated MMSE categories correspond to MMSE scores of 21–26 = mild AD; 15–20 = moderate AD; ≤14 = MS/S AD. Abbreviations. AD, Alzheimer’s disease; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; MS/S, moderately severe/severe.

Clinical and health outcomes

Over 18 months, at the subgroup level, MMSE declined in all AD severity subgroups, with the largest reduction in score from baseline observed in the mild AD subgroup (1.73 points) compared with the moderate AD (1.38 points) and MS/S AD subgroups (0.95; ). MMSE score reductions were statistically significant within each AD severity subgroup (), but between-group differences in mean change from baseline were not (least squares [LS] mean change from baseline to 18 months [95% CI]: mild versus moderate AD, −0.35 [−1.02, 0.32], p = .30; mild versus MS/S AD, −0.77 [−1.94, 0.39], p = .19; moderate versus MS/S AD, −0.42 [1.25, 0.40], p = .32). Functional deterioration, as assessed by decline in ADCS-ADL total score, was also observed within each AD severity group over 18 months () with worsening observed in both basic and instrumental components (Supplementary Figure 1). Mean changes from baseline to 18 months were significantly different between AD severity subgroups for basic ADCS-ADL scores (p < .001) but not for total and instrumental scores (p = .162 and p = .138, respectively; Supplementary Figure 1). Over 18 months, NPI-12 scores did not change significantly from baseline within any of the AD severity groups ().

Table 2. Change from baseline in functional, behavioral, and caregiver burden scores.

In each of the three AD severity subgroups, the mean total ZBI score statistically significantly increased over 18 months. No significant differences were observed between subgroups in the mean change from baseline ZBI score ().

Resource use

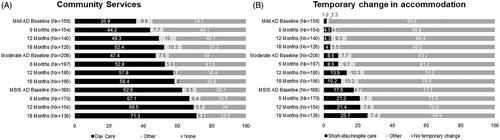

The majority of patients received some form of community service over 18 months, with a higher proportion of patients in the MS/S AD subgroup utilizing community services (). The proportion of patients utilizing community services increased with disease severity at baseline and across 18 months in all three subgroups, with daycare received by the highest proportion of patients ().

Figure 3. Change in social care services received outside of home. (A) The plot shows the proportion of patients who utilized daycare services or other community services (“other”) relative to the proportion of patients who used no community services in the 18-month study period. (B) The plot shows the proportion of patients who temporarily changed to short-stay/respite care or other short-term care outside of the home (“other”) compared with the proportion of patients who remained at home. Abbreviations. AD, Alzheimer’s disease; MS/S, moderately severe/severe; Nx, number of patients with data available.

Table 3. Change in social service use by patients.

The proportion of patients who changed accommodation temporarily outside of their home increased with baseline disease severity although the majority of patients in each group remained at home over 18 months (). Utilization of temporary care accommodation increased over 18 months to 9.5%, 20.5%, and 33.1% of patients in the mild, moderate, and MS/S AD subgroups, respectively. The majority of temporary care accommodation was short-stay/respite care in all subgroups.

The percentage of patients receiving certification of needing support under the Long-term Care Insurance (LTCI), a Japan-specific support system promoting home-based care, was 53.8%, 67.9%, and 88.3% of patients in the mild, moderate, and MS/S AD subgroups, respectively, at baseline, increasing to 66.9%, 77.1%, and 91.2%, respectively, over 18 months. Additionally, 28.6%, 30.3%, and 44.4% of patients in the mild, moderate, and MS/S AD groups, respectively, moved to a higher level of LTCI over 18 months.

Mean total caregiver time was higher at baseline with increase of AD severity (Supplementary Figure 2). However, over 18 months, no significant change was observed in the mean monthly caregiver time within each AD severity subgroup, including the time per month spent on basic ADL, instrumental ADL, and supervision activities (Supplementary Figure 2).

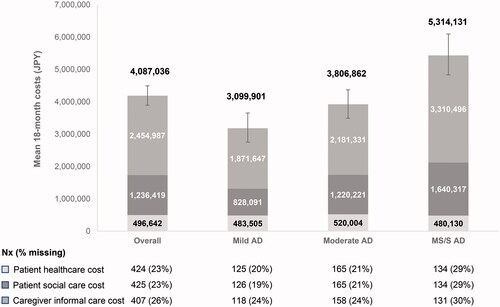

Total societal costs

The cumulative total costs per patient over 18 months increased with AD severity (3.1, 3.8, and 5.3 million JPY [29,006, 35,662, and 49,725 USD] for mild, moderate, and MS/S AD, respectively), with the 95% CIs in the MS/S group non-overlapping with those of the mild and moderate groups (; Supplementary Table 1). Of the three components comprising total societal costs, 18-month patient social care costs (0.8, 1.2, and 1.6 million JPY [7749, 11,418, 15,349 USD] for mild, moderate, and MS/S AD, respectively) and caregiver informal care costs (1.9, 2.2, and 3.3 million JPY [17,513, 20,411, 30,977 USD] for mild, moderate, and MS/S AD, respectively) increased with baseline disease severity, but patient healthcare costs did not (approximately 0.5 million JPY [∼4500–5000 USD] per subgroup). In each disease severity subgroup, over 50% of costs were caregiver informal care costs (; Supplementary Table 1). Sensitivity analyses of total societal costs in which missing data at 18 months were imputed showed similar trends (Supplementary Figure 3).

Figure 4. Mean total societal costs from baseline to 18 months by AD severity. Estimated mean total societal costs of AD per patient in JPY are shown at 18 months, stratified according to baseline AD severity. The number of participants with data available for each subgroup analysis is indicated below the graph (Nx, with percent missing data indicated). Total societal costs (value above each column) are presented for participants with data available (base case); error bars indicate 95% CIs of the mean of total societal costs. The bootstrap method was used to calculate 95% CIs for the mean. An opportunity cost approach was used for working and non-working caregivers; supervision time was excluded from caregiver time. Abbreviations. AD, Alzheimer’s disease; CI, confidence interval; JPY, Japanese yen; MS/S, moderately severe/severe; Nx, number of patients with data available.

Discussion

We report the 18-month analysis of the GERAS-J study, the first prospective observational study evaluating disease burden and associated societal costs of community-dwelling patients with AD and their caregivers in Japan. Over 18 months, cognitive and functional deterioration was observed in each AD severity subgroup, with caregiver burden and resource utilization increasing in parallel. Estimated cumulative total societal costs increased with baseline AD severity, with societal costs at 18 months in the MS/S AD subgroup 1.7 times those in the mild AD subgroup. These findings are in general agreement with those from other country-specific cohorts of the GERAS studyCitation12,Citation22–24 and the broader literatureCitation3,Citation5,Citation11,Citation25–27, supporting an association between worsening disease severity and increasing socioeconomic burden of AD, with informal caregivers particularly affected.

Societal costs of AD and disease severity

Overall, the mean cumulative total societal cost per patient over 18 months was 4.1 million JPY (38,243 USD), with increases associated with disease severity driven by patient social care costs and caregiver informal care costs but not by patient healthcare costs. Caregiver informal costs were the largest cost component, accounting for more than half of the total societal costs, consistent with previously published studies using national statistical data that also identified informal care costs as major components of the total societal costs of AD in JapanCitation11,Citation26. Baseline disease severity appeared to be a key determinant of total societal costs at 18 months, rather than health-related events over the course of the study. However, a previous analysis of patients with mild AD in the GERAS studyCitation16 indicated that clinical progression, in terms of both cognitive and functional decline, was associated with increases in total societal costs over 18 monthsCitation28. It is therefore important to note that MMSE total scores deteriorated over 18 months in GERAS-J, regardless of disease severity at baseline (1.73, 1.38, and 0.95 points in the mild, moderate, and MS/S AD subgroups, respectively), with ≥40% of patients with baseline mild and moderate disease transitioning to a more severe disease category. Given the deterioration in MMSE scores over 18 months in patients with mild to moderate AD, the potential impact of worsening disease should be considered when interpreting our cost analyses based on baseline disease severity categories.

Caregiver burden and AD severity

Substantial physical, psychological, social, and financial burdens are reported by caregivers of patients with dementiaCitation2–5,Citation22–25,Citation27,Citation29–32. Given that caregiver informal costs accounted for over half of total societal costs, understanding the contributing factors is important when determining interventions to relieve caregiver burden and reduce costs. Differences in caregiver burden in dementia have been suggested to be due to multiple patient and caregiver attributesCitation33,Citation34 as well as cultural and country-specific factors that underlie differences in caregiving rolesCitation35, with primary caregivers reporting a higher burden in terms of quality of life, economic burden, and loss of productivity compared with non-primary caregiversCitation36. In GERAS-J, disease severity influenced caregiver burden at baselineCitation12 and at 18 months, which is in line with a prior association reported between greater disease burden and reduced quality of life for both patients and their caregivers in JapanCitation5. Functional decline may also adversely affect caregiver burden in the current study since ADL scores decreased over 18 months in both basic and instrumental components. However, as NPI scores at 18 months did not change from baseline, the observed increase in caregiver burden was not due to the worsening of patients’ behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia.

Despite the increase in caregiver burden, no significant change was observed in mean monthly total caregiver time or time spent on either instrumental or basic ADLs. This may be attributable to patients progressing to the next LTCI level and the associated availability of wide-ranging social care services received outside of the home. Indeed, the majority of patients in GERAS-J received some form of community service, most frequently daycare, with higher usage over 18 months in the group of patients with more severe disease at baseline. A prior analysis of the European GERAS studies similarly found a discordant relationship between caregiver time and burden, with adult-child caregivers reporting a greater burden than spousal caregivers, despite spending less time caringCitation34. The importance of supportive care services in reducing caregiver burden over time is highlighted by a recent study in Australia which reported that caregiver burden increased to a greater degree over a 3-year period for caregivers of patients at home without services compared with caregivers of patients who receive support services or residential careCitation25. In Japan, the LTCI system may contribute to keeping child-aged caregivers working and to reducing the impact of AD on caregiver time. Nonetheless, the increase in ZBI scores in each severity group in the current study indicates that the overall caregiver burden still increased over 18 months, suggesting that current social care services in Japan are insufficient to mitigate completely the negative impact of AD progression on caregiver burden. As the LTCI does not cover psychosocial support for caregivers, it may be important to establish a carer strategy to address the emotional distress and social isolation of caregivers, elements which should be distinguished from measures of caregiving time under the social care system.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study include its prospective, longitudinal design, its Japan-specific cost analyses, and the inclusion of Japanese patients across the spectrum of AD severity in the real-world setting. There are also important limitations to this study. In the Japanese healthcare system, every patient is able to see a specialist at a clinic/hospital without primary care physician intervention or referral. The GERAS-J population was routinely seen for diagnosis and follow-up for dementia due to AD in a memory clinic setting. This may not be entirely representative of the general AD population in Japan, especially for those followed by primary care physicians. The GERAS-J patient population was community-dwelling, and consulted at memory clinics, with dedicated informal caregivers, indicating that these patients may have more severe behavioral or functional problems with dedicated informal caregivers which could result in higher costs than the general AD population. In addition, discontinuations due to institutionalizations and reasons other than death were higher in the higher disease severity subgroups, which may be a potential source of bias in the results. Finally, more than 90% of AD patients were clinically diagnosed by the combination of brain imaging (magnetic resonance imaging, computerized tomography, single photon emission computed tomography, and neuropsychological testing), but this was not confirmed by assessment of beta amyloid pathology. As we observed a small percentage of patients (7.5–9.1%) who moved to a lower stage of severity category over 18 months, it is possible that the study population did not all have amyloid-beta positive AD. Of relevance, Suspected Non-Alzheimer’s Disease Pathophysiology is seen in 17–35% of patients with mild cognitive impairment, and 7–39% of patients with clinically probable AD do not exhibit beta amyloid pathologyCitation37. Recently suppressed AD progression has been reported by appropriate pharmacological managementCitation38 as well as non-pharmacological management by social care use such as daycareCitation39 in Japan. Memory clinic settings and a high proportion of daycare use would cause suppressed AD progression in this study population.

Conclusions

The burden of AD is increasing in an aging society and more detailed, long-term studies of new treatment options are needed to provide cost effective solutions for the management of AD. The current study used a prospective, observational, longitudinal design and a real-world setting to obtain insights into the association between AD severity and disease burden, resource utilization, and societal costs in Japan. The current findings increase our understanding of the socioeconomic impact of AD and are anticipated to inform policy and enable more accurate health economic modeling of AD care globally.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This work was supported by Eli Lilly Japan K.K., Kobe, Japan.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

MN received consulting fees from Eli Lilly and Company outside the submitted work. AI received research grants from Pfizer, CSL Behring, Gilead Science, and Fuji Film, consulting fees from AbbVie, Eli Lilly and Company, Milliman, Novartis Pharma, Novo Nordisk Pharma, and Sony, and lecture fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Creativ Ceutical, CRECON Research and Consulting, and Terumo Corporation. KU, AJMB, TT, and TM are full-time employees and minor shareholders of Eli Lilly and Company. KM has no disclosures to report. MY received lecture fees and grant support from Eli Lilly and Company. MM received speaker’s honoraria from Daiichi Sankyo, Dainippon-Sumitomo Pharma, Eisai, Eli Lilly and Company, Fuji Film RI Pharma, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Mochida Pharmaceutical, MSD, Nippon Chemipher, Novartis Pharma, Ono Yakuhin, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Takeda Yakuhin, Tsumura, and Yoshitomi Yakuhin, and research support from Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Pfizer, Shionogi, Takeda, Tanabe Mitsubishi and Tsumura. HA received lecture fees from Eisai, Takeda, Daiichi-Sankyo, Novartis, and Ono, and received research support from Eisai, MSD, Daiichi-Sankyo, Novartis, Astellas, Dainippon-Sumitomo, Takeda, and Eli Lilly and Company.

Author contributions

MN, AI, KU, AJMB, TT, KM, MY, MM, and HA contributed to the conception and design of the study. AJMB contributed to analysis of the study data. All authors contributed to interpretation of the data, drafting or critical revision of the manuscript, approved the final version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (169.9 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank the study patients and their caregivers, the site investigators, and clinical staff. Medical writing support was provided by Kaye L. Stenvers, PhD and Andrew Sakko, PhD, CMPP, and editorial support was provided by Antonia Baldo, of Syneos Health and funded by Eli Lilly Japan K.K. in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (www.ismpp.org/gpp3).

References

- World Health Organization [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland; 2020. [cited 2020 May 15]. Dementia Fact Sheet. 2019. Available from: www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia.

- Ferrara M, Langiano E, Di Brango T, et al. Prevalence of stress, anxiety and depression in with Alzheimer caregivers. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6(1):93.

- Kamiya M, Sakurai T, Ogama N, et al. Factors associated with increased caregivers' burden in several cognitive stages of Alzheimer's disease. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2014;14(Suppl 2):45–55.

- Kang HS, Myung W, Na DL, et al. Factors associated with caregiver burden in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Psychiatry Investig. 2014;11(2):152–159.

- Montgomery W, Goren A, Kahle-Wrobleski K, et al. Alzheimer's disease severity and its association with patient and caregiver quality of life in Japan: results of a community-based survey. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):141.

- Alzheimer's Disease International [Internet]. London, UK; 2020. [cited 2020 May 15]. World Alzheimer Report 2019. Attitudes to dementia. 2019. Available from: www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2019.pdf.

- Asada T. Prevalence of dementia in Japan: Past, present and future. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2012;52(11):962–964.

- Dodge HH, Buracchio TJ, Fisher GG, et al. Trends in the prevalence of dementia in Japan. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;2012:956354.

- Montgomery W, Ueda K, Jorgensen M, et al. Epidemiology, associated burden, and current clinical practice for the diagnosis and management of Alzheimer's disease in Japan. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2018;10:13–28.

- Sekita A, Ninomiya T, Tanizaki Y, et al. Trends in prevalence of Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia in a Japanese community: the Hisayama Study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;122(4):319–325.

- Sado M, Ninomiya A, Shikimoto R, et al. The estimated cost of dementia in Japan, the most aged society in the world. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):e0206508.

- Nakanishi M, Igarashi A, Ueda K, et al. Costs and resource use associated with community-dwelling patients with Alzheimer's disease in Japan: baseline results from the prospective observational GERAS-J study. JAD. 2020;74(1):127–138.

- McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263–269.

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198.

- National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence. NICE technology appraisal guideline 217. Donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine and memantine for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. 2018. [cited 2019 Jun 21]. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/TA217.

- Wimo A, Reed CC, Dodel R, et al. The GERAS study: a prospective observational study of costs and resource use in community dwellers with Alzheimer’s disease in three European countries–study design and baseline findings. JAD. 2013;36(2):385–399.

- Wimo A, Jonsson B, Karlsson G, et al. Health economics of dementia. Chichester (NY): John Wiley & Sons (US); 1998.

- Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist. 1980;20(6):649–655.

- Galasko D, Bennett D, Sano M, et al. An inventory to assess activities of daily living for clinical trials in Alzheimer's disease. The Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1997;11 Suppl (2):S33–S39.

- Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, et al. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44(12):2308–2314.

- Bloomberg.com [Internet]. 2021. [cited 2018 Apr 6]. Available from: https://www.bloomberg.com/quote/USDJPY:CUR.

- Hager K, Henneges C, Schneider E, et al. Alzheimer dementia: course and burden on caregivers: data over 18 months from German participants of the GERAS study. Nervenarzt. 2018;89(4):431–442.

- Lenox-Smith A, Reed C, Lebrec J, et al. Resource utilisation, costs and clinical outcomes in non-institutionalised patients with Alzheimer's disease: 18-month UK results from the GERAS observational study. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16(1):195.

- Rapp T, Andrieu S, Chartier F, et al. Resource use and cost of Alzheimer's disease in France: 18-month results from the GERAS observational study. Value Health. 2018;21(3):295–303.

- Connors MH, Seeher K, Teixeira-Pinto A, et al. Dementia and caregiver burden: a three-year longitudinal study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;35(2):250–258.

- Hanaoka S, Matsumoto K, Kitazawa T, et al. Comprehensive cost of illness of dementia in Japan: a time trend analysis based on Japanese official statistics. Int J Qual Health Care. 2019;31(3):231–237.

- Reed C, Belger M, Scott Andrews J, et al. Factors associated with long-term impact on informal caregivers during Alzheimer's disease dementia progression: 36-month results from GERAS. Int Psychogeriatr. 2020;32(2):267–277.

- Jones RW, Lebrec J, Kahle-Wrobleski K, et al. Disease progression in mild dementia due to Alzheimer disease in an 18-month observational study (GERAS): the impact on costs and caregiver outcomes. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra. 2017;7(1):87–100.

- Garzon-Maldonado FJ, Gutierrez-Bedmar M, Garcia-Casares N, et al. Health-related quality of life in caregivers of patients with Alzheimer's disease. Neurologia. 2017;32(8):508–515.

- Kawaharada R, Sugimoto T, Matsuda N, et al. Impact of loss of independence in basic activities of daily living on caregiver burden in patients with Alzheimer's disease: a retrospective cohort study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2019;19(12):1243–1247.

- Kawaharada R, Sugimoto T, Tsuboi Y, et al. Delving into the caregiver burden associated basic activity of daily living disability among caregivers of patients with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2020;20(3):263–265.

- Razani J, Kakos B, Orieta-Barbalace C, et al. Predicting caregiver burden from daily functional abilities of patients with mild dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(9):1415–1420.

- Kawano Y, Terada S, Takenoshita S, et al. Patient affect and caregiver burden in dementia. Psychogeriatrics. 2020;20(2):189–195.

- Reed C, Belger M, Dell'agnello G, et al. Caregiver burden in Alzheimer's disease: differential associations in adult-child and spousal caregivers in the GERAS observational study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra. 2014;4(1):51–64.

- Kajiwara K, Kako J, Noto H, et al. Response to “Factors associated with long-term impact on informal caregivers during Alzheimer's disease dementia progression: 36-month results from GERAS". Int Psychogeriatr. 2020;32(2):279–280.

- Igarashi A, Fukuda A, Teng L, et al. Family caregiving in dementia and its impact on quality of life and economic burden in Japan-web based survey. J Mark Access Health Policy. 2020;8(1):1720068.

- Yamada M. Suspected Non-Alzheimer's Disease Pathophysiology (SNAP) and its pathological backgrounds in the diagnosis of preclinical and clinical Alzheimer's disease. Brain Nerve. 2018;70(1):59–71.

- Honjo Y, Ide K, Hajime T. Medical interventions suppressed progression of advanced Alzheimer's disease more than mild Alzheimer's disease. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2020;20(4):324–328.

- Honjo Y, Ide K, Takechi H. Use of day services improved cognitive function in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Psychogeriatrics. 2020;20(5):620–624.