Abstract

Objective

Inadequate communication about endometriosis symptom burden between women and healthcare providers is a barrier for optimal treatment. This study describes the development of the EndoWheel, a patient-reported assessment tool that visualizes the multi-dimensional burden of endometriosis to facilitate patient–provider communication.

Methods

Assessment questions for the tool were developed using an iterative Delphi consensus process. A consensus phase included additional practitioners and specialists to broaden perspectives and select revised statements. Semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted with 13 women with endometriosis to assess the scoring and content of the measures.

Results

Symptoms included in the tool were pelvic pain, vaginal bleeding, bowel/bladder symptoms, energy levels, fertility, impact on activities, emotional and sexual well-being, and self-perceived global health. Additional life impact areas included relationships, social and occupational activity, and self-perception. The 13 interviewees completed the tool in approximately 5–6 min (range 4.0–7.5 min). Most participants (92%) perceived that the tool would enable better patient–provider communication, including addressing symptoms and areas of impact not normally discussed during office visits.

Conclusion

Similar to visual circular tools used in burden assessment of other chronic diseases, the tool may facilitate improved patient dialogue with providers around endometriosis treatment goals and options.

Introduction

Endometriosis is a gynecologic disorder that affects 6–10% of women of reproductive age and has a substantial and multifaceted burdenCitation1–4. The condition is often characterized by chronic pelvic pain and/or infertility and can negatively impact quality of life, intimate relationships, education and work, and emotional well-beingCitation5–12. As seen in other chronic pain conditions, women experiencing chronic pain due to endometriosis may be at risk for depression, anxiety, and chronic fatigueCitation12,Citation13. Women with endometriosis are impacted financially, with healthcare costs ranging from more than $1000–$12,000 per patient per yearCitation14,Citation15. These women report missed work/school due to poorly controlled symptoms, resulting in short- and long-term disability claims, and, based on preliminary studies assessing the occupational impact of endometriosis, the severity of symptoms correlates with productivity lossesCitation16–19. Endometriosis can affect sexual quality of life; negative impacts on desire, satisfaction, and frequency of intercourse are associated with the severity of endometriosis-related dyspareuniaCitation20,Citation21. Concerns about infertility also negatively influence psychosocial well-being in women with endometriosis, with reports that 50% of couples experience conception problemsCitation22.

Women report inadequate communication with healthcare providers regarding the multi-dimensional impact of endometriosis on quality of life and treatment decisions, including difficulty describing pain (85%) and not feeling believed (89%)Citation23. The gap in patient–physician dialogue, dismissal of pain as a normal aspect of menstruation, and misattribution of pain to a purely psychological cause are commonly reported by women with endometriosisCitation22,Citation23.

Visual assessment tools have been developed and used to simplify assessment of disease burden in other chronic health conditions. The PSOdisk and IBD Disk have been developed to facilitate evaluation of psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease, respectively, and provide patients with a graphic representation of the multi-dimensional impact these conditions have on their livesCitation24,Citation25.

Although there are existing patient-reported outcome tools that assess the multi-dimensional burden of endometriosis, they are intended for endometriosis-focused research and are neither quick to complete nor easy to score. This unmet need for a short, clinically useful assessment motivated the development of the EndoWheel (AbbVie Inc., North Chicago, IL, USA), a patient-reported tool that provides immediate visual representation of the broad impact of endometriosis disease burden, expanding beyond just pain or infertility. In this article, we describe the use of an iterative Delphi consensus process utilized to develop the tool.

Methods

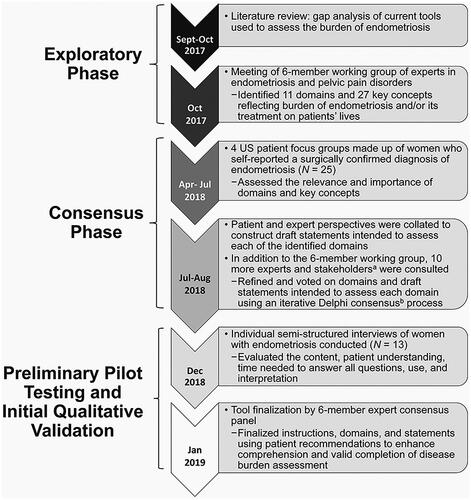

Development of the EndoWheel tool was conducted in several stages: an exploratory phase, consensus phase, and preliminary assessment and finalization phase (). Qualitative design and evaluation of the tool started with an informal literature search on PubMed. Between September and October 2017, a gap analysis of current tools used to assess the disease burden in patients with endometriosis was conducted by the Lighthouse Medical Communications Group (New York, NY, USA). These tools included “EPHect Endometriosis Patient Questionnaire Standard,” “Endometriosis Health Profile,” “NIH PROMIS questionnaires,” “Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36,” “Forquet tool,” “EuroQOL,” and “patient-administered digital applications.” A six-member expert consensus panel of women’s health specialists, which included gynecologists and scientists with expertise in pelvic pain, endometriosis, and reproductive medicine, reviewed the domains and key concepts that described disease impact used in the other assessment tools. These key concepts and domains were then narrowed down, ranked, and voted on using a modified, iterative Delphi process.

Figure 1. Flow chart of the exploratory phase, consensus process, and patient focus group analysis. Timeline of the methods for development of the EndoWheel tool. aIndividuals consulted included a pain specialist, a fertility specialist, general practitioners, community physicians, patient advocates, and patients. bThe Delphi process was used, with voting on a 9-point scale. Consensus was defined as both ≥80% of respondents indicating high agreement scores in the range of 7–9 and ≤20% indicating low agreement scores in the range of 1–3.

Voting on preliminary domains and items by the expert panel working group was conducted in three rounds using a ranking scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 9 (strongly agree), with consensus defined as ≥80% of respondents indicating high agreement scores in the range of 7–9. The expert panel was joined by 10 additional participants for the consensus phase. These participants included general practitioners, community physicians, an additional pain specialist, an additional fertility specialist, patient advocates, and patients, who widened the group’s perspective, and, using an iterative Delphi consensus process, further refined domains and drafted individual burden items for the tool after each round of voting.

To assess the patient perspective on the relevance and importance of the selected domains and determine what burden the domains have on women’s lives, semi-structured qualitative interviews were performed with four patient focus groups of women with endometriosis. A total of 25 women participated in the focus groups, six in the first group and seven in the second group in Dallas, Texas, and six each in both groups in Boston, Massachusetts. Eligibility criteria for participation in the focus group included women aged 18–49 years who self-reported a surgical diagnosis of endometriosis via laparoscopy, laparotomy, or other procedure; were premenopausal or perimenopausal; and could read and understand English.

Patients were not eligible to participate in the focus group if they were currently pregnant; had a history of hysterectomy or oophorectomy; or had cessation of periods for a year due to reasons other than pregnancy, breastfeeding, contraceptive use, or medical treatments for endometriosis. The objective of the focus groups was to obtain feedback on the relevance, importance, and potential burden of the items identified by the clinical expert panel for inclusion on the tool.

After the consensus phase and incorporation of the focus groups’ feedback, the updated tool was assessed in an additional round of individual semi-structured interviews of 13 women with endometriosis to evaluate the content of the tool, define its use, determine patient understanding, and establish the time needed to answer all questions. Interviewees were recruited at two sites, one in Dallas, Texas, and one in Raleigh, North Carolina, for an hour-long interview in December 2018. Women eligible to participate in the interviews were chosen from the same source, and according to the same criteria listed above, as those who participated in the focus groups. Guided interviews began with an introduction to the tool. Participants were then asked to complete the assessment tool without assistance from interviewers. Interviewers recorded participants’ initial reactions, any questions that caused confusion, and length of time taken to complete the tool. No formal hypothesis was tested in this qualitative study and descriptive statistical analysis was performed.

Following a review and exemption by the RTI Health Solutions (Research Triangle, NC, USA) international institutional review board, medical recruiters from Fieldwork (Dallas, TX, USA and Boston, MA, USA) recruited and screened potential focus group participants. Specifically, recruiters identified possible participants using the Fieldwork database of individuals who had previously reported a surgically confirmed diagnosis of endometriosis or those who had expressed interest in participating in qualitative research.

Results

Results from the gap analysis revealed the unmet need for a patient-reported, visual assessment tool that covered the full breadth of impact of endometriosis symptoms on women’s lives that could be completed within the limited time afforded during average office visits. After the multiple aforementioned stages of tool development, the working group reached final consensus to include 10 symptom domains that are reported by women with endometriosis: pelvic pain, vaginal bleeding, bowel and bladder symptoms, energy and fatigue, sexual well-being, fertility, social and recreational activities, work/school/other daily tasks, self-image and perception, and emotional well-being. It is important to note, the tool is not intended to be diagnostic for endometriosis, since many of the symptoms can be caused by other conditions that co-occur in women with endometriosis.

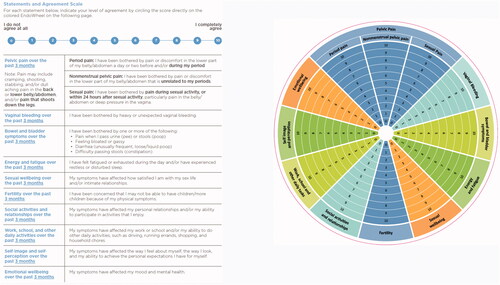

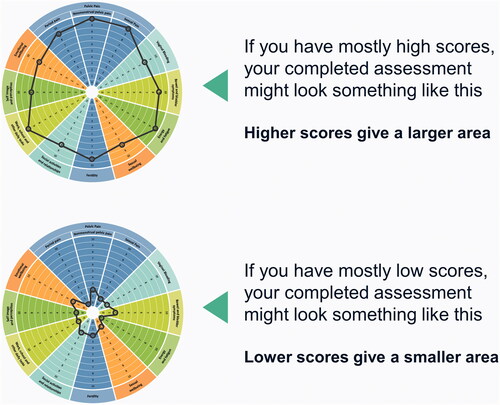

Characteristics of the twenty-five women who participated in one of the four semi-structured focus groups are presented in . Using feedback from these focus groups, the wording and appearance of the 12 statements representing the 10 domains of impact of endometriosis symptoms were refined by the experts based and the final tool is displayed in . The directions instruct women to document their level of agreement on a numeric rating scale from zero (do not agree at all) to 10 (completely agree) with statements pertaining to their symptoms in the past 3 months regarding pelvic pain (period pain, non-menstrual pelvic pain, sexual pain), vaginal bleeding (bothersome, heavy, or unexpected), bowel/bladder symptoms (painful urination or defecation, bloat/gas, diarrhea/constipation), energy and fatigue (daytime exhaustion, restless or disturbed sleep), sexual well-being (satisfaction with sex life or intimate relationships), fertility (concern about ability to have children), relationships, effect on activities (work, school, daily tasks), self-perception (self-image, appearance, ability to achieve personal expectations), and emotional well-being (mood, mental health). Answers are marked within a wedge of the tool. Longer distance from the center of the wheel indicates a greater burden of that endometriosis-associated domain. Adjacent answers can be connected with lines, creating a polygon shape, where a larger surface area indicates an overall greater burden of disease ().

Figure 2. Questionnaire and image of the assessment EndoWheel tool. The tool and the 12 impacts of endometriosis are assessed. Patients are instructed to circle numeric rating scale scores based on their responses to each statement.

Figure 3. Examples of possible completed EndoWheel assessments. The size of the area formed from connecting the scores in each domain allows for visualization of the disease burden.

Table 1. Baseline demographics and characteristics of consensus-phase focus group participants.

Preliminary pilot testing of the proposed tool and its functionality was conducted with 13 individual interviewees (mean age [range] 36.5 years [26–47 years]) in a diverse patient population (). The average self-reported age at surgical diagnosis of endometriosis was 27.7 years (range 16–40 years), with the women experiencing endometriosis-related symptoms anywhere from less than 1 year to 20 years prior to diagnosis. Three participants (23.1%) reported that their only symptom at the time of diagnosis was presentation for fertility testing or treatment. At the time of the interview, three women reported current use of oral contraceptives, two had an intrauterine device, two reported use of other hormone therapy, and one reported use of Lupron Depot (AbbVie Inc., North Chicago, IL, USA) for treatment of endometriosis symptoms; eight women reported no current hormonal treatment. Women treated with hormones reported receiving their current endometriosis treatment regimens for a range of 2–7 years. At screening, all patients reported current symptoms of endometriosis including backache, headache, joint pain, and other pain before and during periods.

Table 2. Baseline demographics and characteristics of preliminary pilot testing and initial qualitative analysis of individual interviewees.

Most patients (92%) reported pelvic/abdominal or lower back pain before or during periods that limited activities or required medication. Patients also reported pain with sexual intercourse (62%), pain with bowel movements before and/or during periods (54%), and pain with urination before and/or during periods (23%).

The mean time for participants to complete their assessment with the tool was 5–6 min (range 4.0–7.5 min). Twelve of 13 participants (92%) perceived that using the tool was acceptable and would enable them to better communicate with their healthcare providers, including addressing symptoms and areas of impact that they did not normally consider raising or have the opportunity to discuss during office visits.

Discussion

Following a Delphi process that incorporated expert-provider insight, patient input, and patient usability refinement, the EndoWheel tool was developed to assess the presence and severity of 10 pertinent health domains of endometriosis. This novel tool has been developed in response to the unmet need for a comprehensive, patient-administered assessment of the multi-dimensional burden of endometriosis. The tool provides patients and providers with an intuitive, graphic, real-time representation of the burden of symptoms and the impact of disease on social and emotional health and ability to function. The assessment wheel captures the impact of endometriosis across health domains patients have identified as being most impactful: pelvic pain, vaginal bleeding, bowel/bladder symptoms, energy levels, and impact on activities, emotional and sexual well-being, and fertility. Vaginal bleeding was included as a health domain because it is commonly reported by women with endometriosisCitation26 but may be due to other etiologies. Further, vaginal bleeding is a common side-effect of all hormonal medications used to treat endometriosis. We felt it was important to assess this symptom, as it is reported to be bothersome by women with endometriosis.

The tool was acceptable to focus groups of women with endometriosis, and the average completion time was 5–6 min. Nearly all participants perceived that using the tool would enable them to communicate better with their healthcare providers, including addressing symptoms and areas of impact that patients did not normally consider sharing or have the opportunity to discuss during office visits.

Women are often reluctant to discuss their full burden of endometriosis-related symptoms because of normalization or stigmatization of pelvic pain, limited time available during appointments to discuss all patient issues, and the multifactorial burden of symptomsCitation16.

Medical, surgical, and complementary treatments for endometriosis have been shown to impact health-related quality of life in womenCitation10; for example, improvements in sexual function and reduction of sexual distress have been reported in patients with endometriosis who received 6 to 24 months of dienogest treatmentCitation27. The tool has the advantage of keeping providers and patients focused on achieving broader wellness goals rather than focusing solely on improvement in menstrual pain or fertility status. Despite its broad coverage, the tool can be completed within the wait time of a normal office visit.

Although the tool can be used in routine clinical care to assess endometriosis-associated symptoms, there is also a potential role for its use in longitudinal studies, clinical trials, quality-improvement programs, or multi-site ambulatory-based pragmatic research projects. Development of various delivery platforms of the tool is ongoing, and electronic application versions are being finalized.

The tool has several limitations in that it is not yet validated in large clinical samples and has not been correlated with previously validated instruments that assess similar domains. Furthermore, the tool was designed to assess the burden of disease in English-speaking adult women from Western countries with self-reported surgical diagnosis of endometriosis and has not been evaluated in other demographic groups at risk for endometriosis. Additionally, studies are also needed to compare changes in disease burden over time and define what constitutes a meaningful change or response to an endometriosis treatment or intervention. The tool is not intended to diagnose endometriosis, and symptoms measured by the tool may not be solely attributed to endometriosis but may reflect comorbidities.

The tool offers advantages over other available assessments because of the intuitive, visual nature of the tool, the short time to complete it, and the focus on multi-faceted impact of symptoms. Although the number of women with endometriosis who contributed to the focus groups and interviews was small, they provide real-world views of symptoms that have the most impact on patients with endometriosis.

It is hypothesized that, when the tool is used longitudinally, the area of the shape created by connecting patients’ scores on the wheel will vary according to the severity of symptoms and current life goals (e.g. fertility goals) and evolve over the disease course and in response to treatment because the spectrum and impact of endometriosis symptoms are not static over time. This longitudinal approach has the potential to provide valuable insight into a patient’s disease journey, including symptom management and overall well-being, while facilitating improved patient-provider communication.

The tool has the potential to impact patient care by facilitating communication between patients and healthcare providers through a convenient presentation of a woman’s multi-dimensional burden of endometriosis. The advantage of self-administration of the tool lies in the generation of explicit agenda items to express and prioritize their concerns and maximize limited time during office visits. The tool may also increase awareness and diminish stigma among women with endometriosis by expanding awareness of the disease’s multi-dimensional impact and by facilitating increased patient–provider communication of symptom burden that may not normally be discussed during routine office visits. Future validation studies are needed with a large, diverse study population of women with endometriosis and also among diverse practitioners to provide more insight into the application of this tool in the general population of women with endometriosis. Specifically, further quantitative validation studies are required to evaluate the psychometric properties of the tool, and larger clinical studies are necessary to assess its ability to facilitate patient–physician discussions about symptoms and effects on quality of life and the impact that this tool-facilitated interaction has on treatment selection and patient-centered outcomes.

Conclusions

The EndoWheel assessment tool, which is similar to visual circular tools used to assess the burden of other chronic diseases, may facilitate improved patient dialogue with providers around endometriosis treatment goals and options.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was supported by AbbVie Inc.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

SA-S has received research support from the National Institutes of Health; honorarium for consultancy for AbbVie, Bayer, Eximis, and Myovant; and author royalties from UpToDate. MRL has received funding from Marriott Family Foundations, royalties from UpToDate, and honorarium for consultancy from AbbVie and NextGen Jane. SAM has received research support from the National Institutes of Health and the Marriott Family Foundations, and honorarium for consultancy from AbbVie, Roche, and Celmatix. AM has received honorarium for consultancy from AbbVie, Allergan, Bayer, and Hologic. KV has received research funding from Bayer AG; speaker’s fees from Bayer AG, Gedeon Richter, Grunenthal GmbH, and Eli Lilly; and honorarium for consultancy from AbbVie, Bayer AG, and Grunenthal GmbH. SE, SC, and AMS are employees of AbbVie and may hold stock and/or stock options. FT has received research support from the National Institutes of Health, speaker’s fees from AbbVie and Medscape, royalties from UpToDate, and honorarium for consultancy from AbbVie and UroShape. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

Conception and design: SA-S, MRL, SAM, AM, KV, SE, SC, AMS, and FT; data acquisition: SA-S, MRL, SAM, KV, SE, SC, and FT; data interpretation: SA-S, MRL, SAM, KV, SE, SC, AM, AMS, and FT; overall responsibility for the accuracy of the data: SA-S; review and critique of the manuscript: all authors; approval of the final manuscript draft submitted for publication: all authors. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work, ensuring the accuracy and integrity of the publication.

Acknowledgements

AbbVie participated in the development, review, and approval of the manuscript; however, the authors maintained full control of the manuscript and determined the final content. The authors would like to thank AbbVie for support of this manuscript. Medical writing support, funded by AbbVie, was provided by Meghan L. Thompson, PharmD, PhD, Kelly M. Cameron, PhD, CMPP, and Kersten Reich, MPH, CMPP, of JB Ashtin, who developed the first draft based on an author-approved outline and assisted in implementing author revisions. JB Ashtin adheres to Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines and International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) recommendations.

Data availability statement

AbbVie is committed to responsible data sharing regarding the studies we sponsor. This includes access to anonymized, individual, and trial-level data (analysis data sets), as well as other information (e.g. protocols and Clinical Study Reports), if the trials are not part of an ongoing or planned regulatory submission. This includes requests for clinical trial data for unlicensed products and indications.

This data set can be requested by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent scientific research and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal and Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) and execution of a Data Sharing Agreement (DSA). Data requests can be submitted at any time and the data will be accessible for 12 months, with possible extensions considered. For more information on the process, or to submit a request, visit the following link: https://www.AbbVie.com/our-science/clinical-trials/clinical-trials-data-and-information-sharing/data-and-information-sharing-with-qualified-researchers.html.

References

- Giudice LC. Clinical practice. Endometriosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(25):2389–2398.

- Shafrir AL, Farland LV, Shah DK, et al. Risk for and consequences of endometriosis: a critical epidemiologic review. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;51:1–15.

- Zondervan KT, Becker CM, Koga K, et al. Endometriosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4(1):9.

- Ghiasi M, Kulkarni MT, Missmer SA. Is endometriosis more common and more severe than it was 30 years ago? J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27(2):452–461.

- Moradi M, Parker M, Sneddon A, et al. Impact of endometriosis on women's lives: a qualitative study. BMC Womens Health. 2014;14:123.

- Fourquet J, Baez L, Figueroa M, et al. Quantification of the impact of endometriosis symptoms on health-related quality of life and work productivity. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(1):107–112.

- Soliman AM, Coyne KS, Zaiser E, et al. The burden of endometriosis symptoms on health-related quality of life in women in the United States: a cross-sectional study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;38(4):238–248.

- Gallagher JS, DiVasta AD, Vitonis AF, et al. The impact of endometriosis on quality of life in adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2018;63(6):766–772.

- DiVasta AD, Vitonis AF, Laufer MR, et al. Spectrum of symptoms in women diagnosed with endometriosis during adolescence vs adulthood. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218(3):324 e321–324 e311.

- Jia SZ, Leng JH, Shi JH, et al. Health-related quality of life in women with endometriosis: a systematic review. J Ovarian Res. 2012;5(1):29.

- Marinho MCP, Magalhaes TF, Fernandes LFC, et al. Quality of life in women with endometriosis: an integrative review. J Womens Health. 2018;27(3):399–408.

- La Rosa VL, De Franciscis P, Barra F, et al. Quality of life in women with endometriosis: a narrative overview. Minerva Med. 2020;111(1):68–78.

- Stratton P, Berkley KJ. Chronic pelvic pain and endometriosis: translational evidence of the relationship and implications. Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17(3):327–346.

- Soliman AM, Yang H, Du EX, et al. The direct and indirect costs associated with endometriosis: a systematic literature review. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(4):712–722.

- Simoens S, Hummelshoj L, Dunselman G, et al. Endometriosis cost assessment (the EndoCost study): a cost-of-illness study protocol. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2011;71(3):170–176.

- Andysz A, Jacukowicz A, Merecz-Kot D, et al. Endometriosis - The challenge for occupational life of diagnosed women: A review of quantitative studies. Med Pr. 2018;69(6):663–671.

- Soliman AM, Coyne KS, Gries KS, et al. The effect of endometriosis symptoms on absenteeism and presenteeism in the workplace and at home. JMCP. 2017;23(7):745–754.

- Soliman AM, Surrey E, Bonafede M, et al. Real-world evaluation of direct and indirect economic burden among endometriosis patients in the United States. Adv Ther. 2018;35(3):408–423.

- Nnoaham KE, Hummelshoj L, Webster P, et al. Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and work productivity: a multicenter study across ten countries. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(2):366–373 e368.

- Barbara G, Facchin F, Meschia M, et al. When love hurts. A systematic review on the effects of surgical and pharmacological treatments for endometriosis on female sexual functioning. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017;96(6):668–687.

- Shum LK, Bedaiwy MA, Allaire C, et al. Deep dyspareunia and sexual quality of life in women with endometriosis. Sex Med. 2018;6(3):224–233.

- Culley L, Law C, Hudson N, et al. The social and psychological impact of endometriosis on women's lives: a critical narrative review. Hum Reprod Update. 2013;19(6):625–639.

- Bullo S. “I feel like I'm being stabbed by a thousand tiny men”: The challenges of communicating endometriosis pain. Health. 2020;24(5):476–492.

- Sampogna F, Linder D, Romano GV, et al. Results of the validation study of the Psodisk instrument, and determination of the cut-off scores for varying degrees of impairment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(4):725–731.

- Ghosh S, Louis E, Beaugerie L, et al. Development of the IBD Disk: a visual self-administered tool for assessing disability in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(3):333–340.

- Singh S, Soliman AM, Rahal Y, et al. Prevalence, symptomatic burden, and diagnosis of endometriosis in Canada: cross-sectional survey of 30 000 women. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2020;42(7):829–838.

- Caruso S, Iraci M, Cianci S, et al. Effects of long-term treatment with Dienogest on the quality of life and sexual function of women affected by endometriosis-associated pelvic pain. JPR. 2019;12:2371–2378.