Abstract

Objectives

To describe the effectiveness of secukinumab in the treatment of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and associated physician satisfaction with secukinumab treatment, in routine clinical practice across five European countries.

Methods

A retrospective analysis of PsA patients receiving secukinumab for ≥4 months in France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UK from March to December 2018. Data based on physician-completed questionnaires at initiation of treatment and at the data collection consultation were collected and used to assess effectiveness.

Results

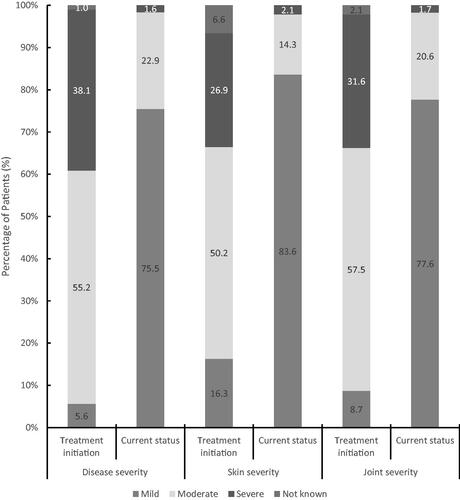

572 PsA patients with a mean age of 47.9 years, 57.0% were male, with 5.6% of patients with mild, 55.2% with moderate and 38.1% severe PsA prior to treatment initiation were included. 33.0% of patients received a dosage of 150 mg and 67.0% a dosage of 300 mg secukinumab. Around 84% of patients received secukinumab for 6 months or longer. Symptoms seen at current assessment in over 20% of patients were tender or swollen joints or psoriatic skin lesions. Between initiation of treatment and the current consultation, improvements in skin, joint and overall severity were reported. Physician satisfaction with secukinumab’s ability to control disease was very high during the study period, greater than 90%, and was seen irrespective of disease severity at initiation, prior biologic use, treatment duration, time since diagnosis or onset of symptoms, treatment history, and BMI.

Conclusion

Physicians were satisfied with the ability of secukinumab to control disease and it was effective in the treatment of PsA patients in routine clinical settings.

Introduction

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic, systemic inflammatory disease that affects peripheral joints, entheseal sites and the axial skeleton. It is associated with psoriasis of the skin and nails and frequently results in reduced physical functioning, and health-related quality of life (HRQoL)Citation1–3. Though once considered a relatively benign diseaseCitation3, it is now clear that PsA represents a complex and heterogeneous phenotype with health consequences beyond joint symptomsCitation4. Treatment of this disease and its various manifestations often needs interdisciplinary teams and a combination of non-pharmacological and pharmacological therapies.

The introduction of biologic disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (bDMARDs), significantly improved outcomes among patients with PsACitation5–7. Both the European League against Rheumatism (EULAR)Citation8,Citation9 and the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA)Citation10 recommend the use of bDMARDs when response to conventional systemic DMARDs (csDMARDs) is inadequate. Inhibitors of tumor necrosis factor (TNFi) were the first class of bDMARDs for PsA, though some patients do not respond, may lack a sustainable response, or present with adverse events that lead to treatment discontinuationCitation11,Citation12. Newer classes of drugs employ different mechanisms of action and include monoclonal antibodies inhibiting the interleukin-17A (IL-17A) receptor or the interleukin 12/23 axisCitation13–15, a selective T cell co-stimulation modulatorCitation16, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitorCitation17, oral Janus kinase inhibitorsCitation18. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and TNFα are known to be involved in the pathogenesis of rheumatic disease and novel therapeutic approaches are being developed in this contextCitation19.

Secukinumab is a high-affinity, human immunoglobulin G1 monoclonal antibody that selectively binds to and neutralizes IL-17A. IL-17A is a cytokine known to exist in the circulation, jointsCitation20, and skin plaques of patients with PsA. The involvement of IL-17 in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases is well recognizedCitation21 and its levels have been shown to correlate with measures of disease activity and joint structural damageCitation22. Secukinumab has demonstrated clinical benefits in the development programs for PsACitation14 and other immune-mediated inflammatory diseases such as psoriasis and ankylosing spondylitisCitation23,Citation24. The phase 3 FUTURE 1 trial showed 78.1% (secukinumab 150 mg) and 74.8% (secukinumab 75 mg) of patients had no radiographic progression (≤0.5 increase in van der Heijde modified total Sharp score, mTSS) through week 156 of follow upCitation25, while a further study showed that remission and drug retention rates in routine care are favorable. After 6 months 35% of the patients achieved DAS28-CRP remission while the retention rate was 86%Citation26.

With demonstrated efficacy in clinical trials, it remains important to understand secukinumab’s ability to control disease in routine clinical settings, and currently there is a paucity of real-world data relating to secukinumab effectiveness. The aim of this study, involving different medical specialties in five European countries, was to therefore assess the effectiveness of secukinumab in controlling PsA and physician satisfaction with treatment in a routine clinical practice population.

Methods

Study design and data

A retrospective analysis of a large cross-sectional survey was performed using data collected as part of the Adelphi Disease Specific Program conducted in France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UK from 01 March 2018 to 30 December 2018. The Disease Specific Programme (DSP) is an established methodology widely used across multiple disease areasCitation27 comprising large, multinational, non-interventional surveys conducted in real-world clinical practice that describe current disease management, disease-burden impact, and associated treatment effects.

A geographically representative sample of physicians were recruited to participate in the DSP, and were identified by fieldwork agents from publicly available lists and screened for eligibility. Rheumatologists and dermatologists from the 5 European countries who were currently treating patients with PsA were eligible for inclusion and gave consent to participate. Enrolled physicians completed patient record forms (PRFs) for up to 6 consecutive consulting adults with a diagnosis of PsA who visited the physician for routine care, to mitigate against selection bias. No tests, treatments, or investigations were performed as part of this survey, and physicians could only report on data they had to hand at the time of the consultation. Completion of the physician-reported questionnaire was undertaken through consultation of existing patient clinical records, as well as the judgement and diagnostic skills of the respondent physician. Data were collected at the time of consultation to mitigate against recall bias. Missing data were not imputed; therefore, the base of patients for analysis could vary from variable to variable and is reported separately for each analysis.

Patients included in this analysis had been taking secukinumab for a minimum of 4 months prior to study entry and had complete data from the initiation of secukinumab up to the data collection consultation. Patients were not excluded based on prior treatment, duration of disease or comorbidities.

Outcomes

Outcomes collected in this study were related to patient demographics and clinical characteristics, treatment effectiveness and physician satisfaction with secukinumab treatment.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Demographic information including age, gender, body mass index (BMI), ethnicity and employment status together with time since diagnosis, was collected from the PRFs. Clinical characteristics included physician-reported severity, clinical symptoms and comorbidities selected by physicians from a predefined list. Clinical and subjective physician’s assessments from the PRF were used to describe the effectiveness of treatment and physician satisfaction with treatment. Treatment history of patients was collected, specifically use of prior advanced therapies (bDMARDs or targeted synthetic DMARDs [tsDMARDs]).

Treatment effectiveness

Clinical improvement was evaluated by comparing physician assessments at the data collection consultation with those at treatment initiation, with patients grouped according to treatment duration (≥4–<6 months, ≥6–<12months, ≥12 months). As this was a point in time study, longitudinal data were not collected; these treatment duration groups were mutually exclusive. Physicians were asked to report current severity (at time of consultation/recruitment) as well as initial severity (prior to treatment initiation, where data were available from patient medical records). The minimum time of 4 months between treatment initiation to data collection consultation was chosen to reflect the initial loading phase and 12 weeks of maintenance therapy and allowed time for physicians to establish both treatment effect and treatment satisfaction.

Clinical assessments based on retrospective completion of the PRFs or medical records, using validated tools to assess devious aspects of disease severity. These tools included the physician global assessment visual analogue scale (VAS 0–100, 0 for the best possible and 100 for the worst health assessment), pain (numeric rating scale 1–10, 1 representing no pain and 10 worst possible pain), Disease Activity Score-28 (DAS28)Citation28, Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI)Citation29 body surface area (BSA) and swollen (66) and tender joint count (68)Citation30. Physicians used these formal tools, alongside existing medical records, to define a physician-rated for overall disease severity (either mild, moderate, severe) and change in disease status (either improving, stable, unstable, deteriorating slowly, deteriorating rapidly) using their professional judgement, which is entirely consistent with decisions made in routine clinical practice.

Physician satisfaction with secukinumab treatment

For satisfaction with secukinumab treatment, physicians were asked “Which option best describes your satisfaction with the control the current treatment approach is providing for this patient?” Physician reported satisfaction was assessed using a 5-point Likert scale, with responses available comprising “very dissatisfied,” “dissatisfied,” “neither satisfied or dissatisfied,” “satisfied” and “very satisfied.” Physicians who answered “Very dissatisfied” or “Dissatisfied” were classed as dissatisfied and physicians who selected the mid-value “neither satisfied or dissatisfied” were classed as neutral. Satisfaction was collected at the data collection consultation, so time on treatment varies for each patient.

Statistical methods

This was a point-in-time, non-interventional study. The analysis involved descriptive statistics; where appropriate the proportion of patients, mean values with standard deviation (SD) were reported.

Satisfaction analyses were grouped by the following baseline characteristics: treatment duration (≥4–<6 months, ≥6–<12months, ≥12 months), previous treatment with biologic therapy, physician-reported disease severity (mild, moderate, severe), time since diagnosis (<1 year, 1–5 years, >5 years), time since onset of symptoms (<1 year, 1–5 years, >5 years), concomitant use of csDMARDs, BMI (<25, 25–29.9 and 30+) and weight (<90 kg, ≥90 kg). Effectiveness analyses were grouped by treatment duration (≥4–<6 months, ≥6–<12months, ≥12 months).

Ethical considerations

Using a check box, physicians provided informed consent to participate in the survey. All responses were anonymised and all participating physicians and patients were assigned a study number to ensure anonymous data collection.

The research was conducted in accordance with national market research and privacy regulations (EphMRA, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services National Institutes of Health, HIPAA). Ethical approvals were sought and granted through the Freiburg Ethics Commission (FEKI – study number 02018/1077).

This study was designed, conducted and reported in accordance with the Guidelines for Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices (GPP) of the International Society for Pharmaco-epidemiologyCitation31, the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelinesCitation32.

Results

294 rheumatologists and 144 dermatologists provided data for 572 patients with PsA; 38 from France, 105 from Germany, 113 from Italy, 159 from Spain and 157 from the UK.

Demographics and clinical characteristics

The mean (SD) age of patients was 47.9 (11.7) years, 57.0% were male, 94.8% were white/Caucasian, with a mean (SD) BMI of 26.6 (4.4) (). The most common comorbidities were current psoriasis (19.8%), hypertension (17.7%), hyperlipidemia (12.9%), anxiety (12.2%), depression (10.5%), diabetes (10.3%), and obesity (10.0%). Psoriasis was diagnosed before PsA in 416 (72.7%) patients with only 46 (8.0%) patients having a diagnosis of PsA before psoriasis. The remaining patients never had a formal diagnosis of psoriasis (only PsA) or were diagnosed with PsO and PsA at the same time.

Table 1. Demographics, clinical characteristics, and treatment patterns of study population.

Of the 447 patients with information on the time since PsA diagnosis, 6.5% were diagnosed within the last year, 57.5% within a period of between one and 5 years and 34% had been diagnosed for longer than 5 years with the mean time since diagnosis of 5.6 years. (). The time since the onset of symptoms was longer with a mean (SD) of 6.7 (7.4) years. Based on a pre-defined list, physicians reported tender joints, swollen joints, psoriatic skin lesions, enthesitis and dactylitis for 41.3%, 23.4%, 36.9%. 7.2% and 6.5% of patients respectively while no current manifestations were reported for 35% of the patients.

Most patients had experience with other medications, given the mean time since diagnosis of over 5 years. The majority of the patients (78.1%) had received on average (SD) 1.5 (0.7) csDMARDs at any time point before receiving advanced therapy (bDMARDs or tsDMARDs). Within the advanced therapies group, 58.9% were currently on the first line, 24.5% on second line and 16.6% had received more than two lines [mean (SD) 1.7 (1.1)] of advanced therapies; 41.1% had experienced another biologic therapy. Physicians reported that currently prescribed PsA medications included csDMARDs (24.8%), non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs, 15.9%), and COX-2 inhibitors (9.3%).

The largest proportion of patients (52.6%) received secukinumab as monotherapy, 24.8% received a concomitant csDMARD and the remainder (22.6%) received a concomitant non-csDMARD. The majority of patients (66.4%) received secukinumab loading dose 300 mg, 26.3% received 150 mg loading dose while for 4.9% of the patients, the information was recorded as receiving a dose outside of 150 mg or 300 mg.

Real world effectiveness of secukinumab

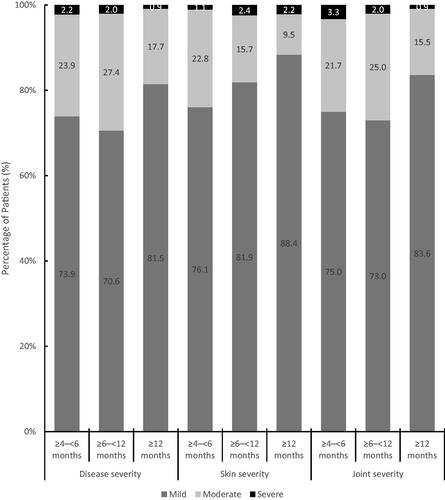

In total, 16.1% of patients in this cohort were treated for ≥4–<6 months, 43.4% were treated for ≥6–<12 months and 40.6% were treated for 12 months or longer. Notable improvements in overall disease severity were observed as the proportion of patients being categorised with mild disease (5.5%) at treatment initiation shifted to 75.5% at the data collection consultation. Similar shifts in severity were observed for the skin and joint involvement (). These benefits were established after 4–6 months of treatment, were higher in patients after 12 months for skin and joint measures and to a lesser extent for the assessment of overall disease severity ().

Figure 1. Physician-reported disease severity at treatment initiation and current status. Physician-reported severity for overall PsA and for skin severity and joint severity were reported at the initiation of treatment and at the current/latest status with at least 4 months of secukinumab treatment. Patients were assessed with either mild, moderate, or severe disease. For a small number of patients, disease status was unknown.

Figure 2. Physician reported severity as a function of duration of secukinumab therapy. The changes in overall severity together with skin severity and joint severity were assessed by physicians according to the duration of secukinumab therapy. Changes in the percentage of patients with mild, moderate, or severe disease were assessed according to treatment duration of 4‒6 months, 6‒12 months, and 12 months or longer.

Improvements in patient and physician global VAS scores, DAS28 score, tender and swollen joint counts, BSA, PASI score as well as higher proportion of patients achieving BSA < 3% and PASI score < 3 were observed (). A similar pattern was also observed in the percentage of patients assessed as stable or improving which increased from 6.5% at the treatment initiation to over 93% at the data collection consultation. Prior biologic experience did not show a notable impact on the effectiveness of secukinumab ().

Table 2. Real-world effectiveness of secukinumab treatment at initiation of treatment, current treatment and stratified according to duration of therapy.

Table 3. Real-world effectiveness of secukinumab treatment according to biologic experience.

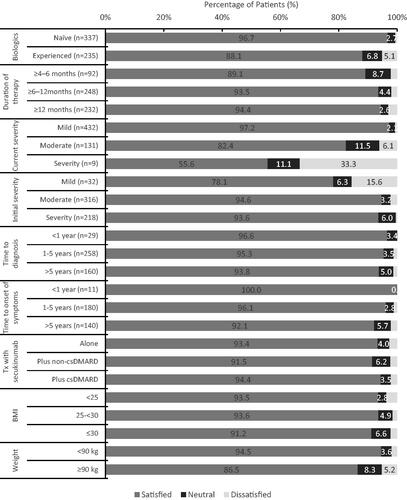

Physician satisfaction with secukinumab treatment was analyzed by overall physician-rated disease severity (mild/moderate/severe) at treatment initiation, current severity, prior biologic use, treatment duration, time since diagnosis and time since onset of symptoms, treatment history, and BMI/weight (). Across variables as such as demographics, disease characteristics at treatment initiation and clinical variables, physician satisfaction in disease control was high, greater than 90% across these variables. For a small group of nine patients with severe current disease, physician satisfaction with treatment was lower at 55%.

Figure 3. Physician reported satisfaction in disease control by key clinical variables. Physician satisfaction was assessed according to key clinical variables according to a scale of “satisfied”, “neither satisfied or dissatisfied” and “dissatisfied” for 572 patients with at least 4 months of secukinumab treatment.

Discussion

Early and sustained benefit of secukinumab treatment in patients with PsA treated in routine clinical settings across five European countries was reported in this cross-sectional study. Physician-reported effectiveness for secukinumab was consistent across multiple outcomes and irrespective of initial overall disease, skin or joint severity. The reported benefits for secukinumab across the overall disease severity, the individual measures of skin severity (BSA, PASI) and joint severity (DAS28, TJC, SJC) were also independent of time since diagnosis and prior exposure to other biologics.

These data are consistent with the randomized controlled FUTURE 1 and 2 phase III studiesCitation14,Citation33 and also the respective extension studies for which data up to 5-years have been reportedCitation34,Citation35. The demographics and clinical characteristics suggest that the current study population showed many similarities to the patients enrolled in the secukinumab phase III studies; for example with similar mean age (47.9 vs. 49.6), physician global VAS (59.4 vs. 58.3), patient global VAS (56.7 vs. 55.2), PASI (17.2 vs. 15.6) and DAS28 (5.2 vs. 4.8)Citation14.

As well as similarities to the RCT findings, recent preliminary observational data has also demonstrated the effectiveness of secukinumab in a real-world setting. The European Spondyloarthritis Research Collaboration (EuroSpA) including 12 European registries and 1543 patients with PsA treated with secukinumab in routine clinical settings reported that overall 6/12-month secukinumab retention rates were 86%/74% and were significantly higher in b/tsDMARD-naïve patients at 12, but not 6 monthsCitation36. While a formal statistical comparison was not undertaken in the current analysis, the results shown in suggest that the effectiveness of secukinumab in terms of disease status, pain and BSA is independent of prior exposure to biologics.

Analysis of treatment patterns from administrative claims data showed that in US settings in 2015 around 45% of patients who continued biologic use for longer than 90 days received one or more concomitant medications, most commonly corticosteroids (22.0%), opioids (17.1%), or NSAIDs (12.9%)Citation37. Concomitant medication use was also shown in the current study with NSAIDs commonly used by 1 in 6 patients (15.9%) although concomitant steroid use (topical or oral) was less frequent in this study population (12.7%).

High levels of physician satisfaction with secukinumab treatment irrespective of clinical parameters, time since diagnosis or onset of symptoms, and previous exposure to biologics were reported in this study. In another real-world evidence study conducted in Latin American PsA patients and physicians, physician levels of satisfaction with biologic treatments in PsA were lower than observed in this studyCitation38. Previous research has suggested that up to a quarter of PsA patients and physicians were misaligned over treatment satisfaction, with more physicians dissatisfied than patients in the misaligned groupCitation39.

This study has a number of limitations, including selection bias, where possibly patients with increased consultations were more likely to be included. Furthermore, patients who did not respond or were intolerant to secukinumab were excluded, as patients were only included if on treatment for more than 4 monthsCitation34. Dermatologists and rheumatologists may not have equivalent expertise in assessing joint and skin involvement in PsA. There was also a lack of source data verification, no formal inclusion criteria were applied other than physician-stated diagnosis. As this was a point-in-time, non-interventional study, all data analyses were descriptive and confounding factors were not taken into consideration.

These limitations should be balanced against methodological strengths, which include recruitment of a large, representative sample of patients with PsA across multiple European countries, from two specialty physician practices, using standardized data collection tools and an established methodologyCitation27.

Conclusions

In routine clinical practice of PsA patients, secukinumab treatment improved overall disease severity as well as joint and skin severity. It also resulted in an improvement of disease severity after 4 months of treatment and these benefits continued in patients who were treated for longer periods. This study also provided insight into physician satisfaction with secukinumab in a real-world clinical setting and showed that physicians reported high levels of satisfaction with the ability of secukinumab to control PsA disease activity, and this level of satisfaction did not depend on clinical disease characteristics.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study and article processing charges were funded by Novartis.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

PGC reports speaker fees or consultancies with AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BMS, Eli Lilly, Galapagos, Gilead, Novartis and Pfizer. UK has received grant and research support and consultancy fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Biocad, Biogen, Chugai, Eli Lilly, Fresenius, Gilead, Grünenthal, GSK, Hexal Janssen, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche and UCB. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the whole work, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Acknowledgements

Editorial support was provided by David Whitford on behalf of Adelphi Real World and was funded by Novartis. PGC is supported in part by the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Leeds Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The non-interventional, observational nature of the data collection does not result in patients being placed at risk from the study. Physicians and patients provided informed consent to participate in the study and did not provide any personally identifiable information. All responses were anonymized to preserve respondent (physician and patient) confidentiality and all participating physicians and patients were assigned a study number to aid anonymous data collection and to allow linkage of data during data collection and analysis.

The research was conducted in accordance with national market research and privacy regulations (EphMRA, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services National Institutes of Health, HIPAA). Ethical approvals were sought and granted through the Freiburg Ethics Commission (FEKI - study number 02018/1077).

This study was designed, implemented and reported in accordance with the Guidelines for Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices (GPP) of the International Society for Pharmacoepidemiology, the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines, and with the ethical principles laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki.

References

- Gladman DD. Early psoriatic arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2012;38(2):373–386.

- Lee S, Mendelsohn A, Sarnes E. The burden of psoriatic arthritis: a literature review from a global health systems perspective. P T. 2010;35(12):680–689.

- Ogdie A, Weiss P. The epidemiology of psoriatic arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2015;41(4):545–568.

- Husni ME. Comorbidities in psoriatic arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2015;41(4):677–698.

- Antoni C, Krueger GG, de Vlam K, et al. Infliximab improves signs and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis: results of the IMPACT 2 trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(8):1150–1157.

- Mease PJ, Gladman DD, Ritchlin CT, Adalimumab Effectiveness in Psoriatic Arthritis Trial Study Group, et al. Adalimumab for the treatment of patients with moderately to severely active psoriatic arthritis: results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(10):3279–3289.

- Mease PJ, Kivitz AJ, Burch FX, et al. Etanercept treatment of psoriatic arthritis: safety, efficacy, and effect on disease progression. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(7):2264–2272.

- Gossec L, Smolen JS, Gaujoux-Viala C, European League Against Rheumatism, et al. European League Against Rheumatism recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(1):4–12.

- Gossec L, Smolen JS, Ramiro S, et al. European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies: 2015 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(3):499–510.

- Coates LC, Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, et al. Group for research and assessment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis 2015 treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(5):1060–1071.

- Merola JF, Lockshin B, Mody EA. Switching biologics in the treatment of psoriatic arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2017;47(1):29–37.

- Ritchlin C, Rahman P, Kavanaugh A, on behalf of the PSUMMIT 2 Study Group, et al. Efficacy and safety of the anti-IL-12/23 p40 monoclonal antibody, ustekinumab, in patients with active psoriatic arthritis despite conventional non-biological and biological anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy: 6-month and 1-year results of the phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised PSUMMIT 2 trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(6):990–999.

- McInnes IB, Kavanaugh A, Gottlieb AB, et al. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: 1 year results of the phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled PSUMMIT 1 trial. Lancet. 2013;382(9894):780–789.

- Mease PJ, McInnes IB, Kirkham B, et al. Secukinumab inhibition of interleukin-17A in patients with psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(14):1329–1339.

- Nash P, Kirkham B, Okada M, et al. Ixekizumab for the treatment of patients with active psoriatic arthritis and an inadequate response to tumour necrosis factor inhibitors: results from the 24-week randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled period of the SPIRIT-P2 phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10086):2317–2327.

- Mease PJ, Gottlieb AB, van der Heijde D, et al. Efficacy and safety of abatacept, a T-cell modulator, in a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III study in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(9):1550–1558.

- Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, Gomez-Reino JJ, et al. Treatment of psoriatic arthritis in a phase 3 randomised, placebo-controlled trial with apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(6):1020–1026.

- Gladman D, Rigby W, Azevedo VF, et al. Tofacitinib for psoriatic arthritis in patients with an inadequate response to TNF inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(16):1525–1536.

- Cantatore FP, Maruotti N, Corrado A, et al. Anti-angiogenic effects of biotechnological therapies in rheumatic diseases. Biologics. 2017;11:123–128.

- Kagami S, Rizzo HL, Lee JJ, et al. Circulating Th17, Th22, and Th1 cells are increased in psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130(5):1373–1383.

- Murdaca G, Colombo BM, Puppo F. The role of Th17 lymphocytes in the autoimmune and chronic inflammatory diseases. Intern Emerg Med. 2011;6(6):487–495.

- Menon B, Gullick NJ, Walter GJ, et al. Interleukin-17 + CD8+ T cells are enriched in the joints of patients with psoriatic arthritis and correlate with disease activity and joint damage progression. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(5):1272–1281.

- Baeten D, Baraliakos X, Braun J, et al. Anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody secukinumab in treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;382(9906):1705–1713.

- Langley RG, Elewski BE, Lebwohl M, et al. Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis–results of two phase 3 trials. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(4):326–338.

- Mease PJ, Kavanaugh A, Reimold A, et al. Secukinumab in the treatment of psoriatic arthritis: efficacy and safety results through 3 years from the year 1 extension of the randomised phase III FUTURE 1 trial. RMD Open. 2018;4(2):e000723.

- Michelsen B, Heegaard Brahe C, Jacobsson LTH, et al. Remission and drug retention rates of secukinumab in 1549 patients with psoriatic arthritis treated in routine care – pooled data from the observational EUROSPA research collaboration network. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:1281–1282.

- Anderson P, Benford M, Harris N, et al. Real-world physician and patient behaviour across countries: disease-specific programmes – a means to understand. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(11):3063–3072.

- van der Heijde DM, van 't Hof MA, van Riel PL, et al. Judging disease activity in clinical practice in rheumatoid arthritis: first step in the development of a disease activity score. Ann Rheum Dis. 1990;49(11):916–920.

- Fredriksson T, Pettersson U. Severe psoriasis-oral therapy with a new retinoid. Dermatologica. 1978;157(4):238–244.

- Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M, et al. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary core set of disease activity measures for rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. The Committee on Outcome Measures in Rheumatoid Arthritis Clinical Trials. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36(6):729–740.

- Public Policy Committee ISoP. Guidelines for good pharmacoepidemiology practice (GPP). Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2016;25(1):2–10.

- Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, STROBE initiative, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):W163–W94.

- McInnes IB, Mease PJ, Kirkham B, et al. Secukinumab, a human anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriatic arthritis (FUTURE 2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9999):1137–1146.

- McInnes IB, Mease PJ, Ritchlin CT, et al. Secukinumab sustains improvement in signs and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis: 2 year results from the phase 3 FUTURE 2 study. Rheumatology. 2017;56(11):1993–2003.

- Mease PJ, Kavanaugh A, Reimold A, FUTURE 1 study group, et al. Secukinumab provides sustained improvements in the signs and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis: final 5-year results from the phase 3 FUTURE 1 study. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2020;2(1):18–25.

- Michelsen B, Georgiadis S, DI Giuseppe D, et al. SAT0430 Secukinumab effectiveness in 1543 patients with psoriatic arthritis treated in routine clinical practice in 13 European countries in the EuroSpA Research Collaboration network. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79(Suppl 1):1169.2–1171.

- Walsh JA, Adejoro O, Chastek B, et al. Treatment patterns among patients with psoriatic arthritis treated with a biologic in the United States: descriptive analyses from an administrative claims database. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2018;24(7):623–631.

- Soriano ER, Zazzetti F, Alves Pereira I, et al. Physician-patient alignment in satisfaction with psoriatic arthritis treatment in Latin America. Clin Rheumatol. 2020;39(6):1859–1869.

- Furst DE, Tran M, Sullivan E, et al. Misalignment between physicians and patient satisfaction with psoriatic arthritis disease control. Clin Rheumatol. 2017;36(9):2045–2054.