Abstract

Objective

During COVID-19, access to trustworthy news and information is vital to help people understand the crisis. The consumption of COVID-19-related information is likely an important factor associated with the increased anxiety and psychological distress that has been observed. We aimed to understand how people living with a kidney condition access information about COVID-19 and how this impacts their anxiety, stress and depression.

Methods

Participants living with chronic kidney disease (CKD) were recruited from 12 sites across England, UK. Respondents were asked to review how often they accessed and trusted 11 sources of potential COVID-19 information. The Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale–21 Items was used to measure depression, anxiety and stress. The 14-item Short Health Anxiety Inventory measured health anxiety.

Results

A total of 236 participants were included (age 62.8 [11.3] years, male [56%], transplant recipients [51%], non-dialysis [49%]). The most frequently accessed source of health information was television/radio news, followed by official government press releases and medical institution press releases. The most trusted source was via consultation with healthcare staff. Higher anxiety, stress and depression were associated with less access and trust in official government press releases. Education status had a large influence on information trust and access.

Conclusions

Traditional forms of media remain a popular source of health information in those living with kidney conditions. Interactions with healthcare professionals were the most trusted source of health information. Our results provide evidence for problematical associations of COVID-19 related information exposure with psychological strain and could serve as an orientation for recommendations.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a contagious disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). In March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the virus a global pandemic and, as of July 2021, it has been attributed to over 4 million deaths making it one of the deadliest pandemics in history. It is now well established that COVID-19 disproportionally affects those living with a kidney condition increasing risk of severe infection-related complications and poor prognosis including higher possibility of hospitalization, intensive care admission and deathCitation1–4.

During the pandemic, the role of health information has become especially important, and access to trustworthy news and information has been vital in helping people understand the COVID-19 crisis, and what they can do to protect themselves, those they care about and their wider communities. Today, people access information from many other sources beyond traditional news media – governments, health organizations, healthcare staff and other experts, friends, and family – and they rely on various platforms for information about COVID-19, such as social media and celebrities. Nonetheless, this vast volume of information around COVID-19 – and the ambiguity, uncertainty, and often low-quality, confusing or false nature of some of this information – is captured by the WHO’s use of the term “infodemic”Citation5. A key factor likely to influence what information people both access and act upon is their trust in the sources themselvesCitation6. Understanding trusted and frequently accessed sources of information is important to enable effective communication and formulating key messagesCitation7.

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a state of uncertainty and unprecedented sense of threat. Numerous studies have demonstrated that COVID-19 has resulted in increased levels of depression, anxiety and distressCitation3,Citation8,Citation9 for many, including those with CKD and on dialysisCitation10 – a group already at risk of a disproportionately high burden of mental health disordersCitation11. The consumption of COVID-19-related media coverage is likely an important factor associated with some of the anxiety and psychological distress observedCitation12–14. Increased frequency, duration and diversity of COVID-19 information exposure has been associated with symptoms of depression and anxietyCitation12,Citation15,Citation16.

In this present study, we used survey data to understand how people living with a kidney condition access information about COVID-19, how they rate the trustworthiness of the different sources they rely on, and how this impacts their anxiety, stress and depression around their health. The aims were as follows: (1) to explore the most frequently accessed sources for COVID-19 information; (2) to explore the most trusted sources for COVID-19 information; (3) to investigate the association between health information sources with anxiety and depression; (4) to explore factors predicting information health information access and trust.

Methods

This analysis uses data collected as part of a larger multicentre study (DIMENSION-KD) which was adapted in 2020 in response to the developing COVID-19 pandemic. The cross-sectional data used here pertains to data collected between May and June 2021, during which time England was under partial lockdown restrictions after an extensive full lockdown in response to the second wave earlier in the year. All participants provided informed online consent and the study was approved by the Leicester Research Ethics Committee.

Participants

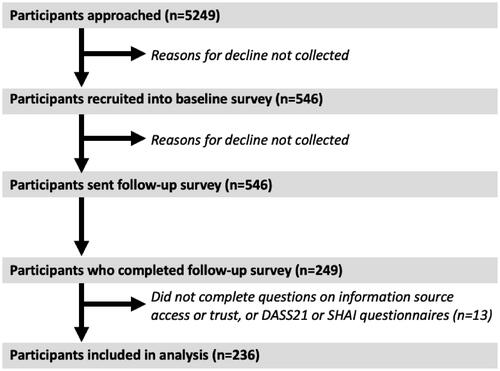

Participants were recruited from 12 sites across England, UK. The inclusion criteria were as follows: aged 18 years or older, not receiving current renal replacement therapy (e.g. dialysis), being able to provide informed consent. Participants were approached if they had completed an initial survey performed by our group on COVID-19 between August and November 2020. Potential participants were sent a link to a follow-up online survey consisting of various questions around the COVID-19 pandemic, changes to their health and lifestyle, and validated questionnaires around their anxiety, stress and depression (detailed below). A modified CONSORT diagram is shown in .

Health information sources

Respondents were asked to review the following 11 sources of potential COVID-19 information: television/radio news; other television/radio programmes, for example, documentaries; newspapers; conversations with family and friends; conversations with colleagues; consultation with healthcare staff; websites or online news pages; social media (e.g. Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, WhatsApp); official government press releases; medical institution press releases; and celebrities and social media influencers. Participants were asked how much they trusted the following sources of information about COVID-19 (on a Likert scale between “1 – Very little trust” and “7 – A great deal of trust”) and how often they accessed the following sources of information about COVID-19 (on a Likert scale between “1 – Never” and “7 – Several times a day”). To facilitate analysis, each source was given a mean score out of 7, with higher scores denoting more frequent access or greater trust. Participants were also asked what type of information about COVID-19 they needed the most, responding “yes” or “no” to a series of statements. These questions were adapted from the WHO “behavioural insights on COVID-19” survey.

Anxiety, stress and depression

Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale–21 items

The Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale–21 items (DASS-21) is a set of three self-report scales designed to measure the emotional states of depression, anxiety and stressCitation17. Each of the three DASS-21 scales contains 7 items, divided into subscales with similar content. The depression scale assesses dysphoria, hopelessness, devaluation of life, self-deprecation, lack of interest/involvement, anhedonia and inertia. The anxiety scale assesses autonomic arousal, skeletal muscle effects, situational anxiety and subjective experience of anxious affect. The stress scale is sensitive to levels of chronic non-specific arousal. It assesses difficulty relaxing, nervous arousal, and being easily upset/agitated, irritable/over-reactive and impatient. Scores for depression, anxiety and stress were calculated by summing the scores for the relevant items. The DASS-21 has been used in research related to COVID-19 and has shown good internal consistency across a range of populationsCitation18.

Short Health Anxiety Inventory

The 14-item Short Health Anxiety Inventory (SHAI) measures health anxiety in medical and non-medical contextsCitation19. Each item of the SHAI consists of a group of four statements in which an individual selects the statement that best reflects their feelings over the past 6 months (1 week in some studies). Item scores are weighted 0–3 and were summed to obtain a total score out of 42; a higher score indicates greater health anxietyCitation20.

Statistical analysis

The association of health information sources with anxiety and depression was assessed using fully adjusted general linear models (i.e. does access/trust in sources explain the variance in anxiety and depression measured using the DASS-21 and SHAI). Models were adjusted for type of kidney disease, age, sex, ethnicity and the number of comorbidities. Data is presented as beta coefficient and significance value. Factors (sex, ethnicity, age, education level, type of kidney disease, number of comorbidities) associated with difference access and trust in sources was explored using fully adjusted ordinal regression models. Data is presented as estimate coefficient and significance value. Significance was recognized as p < .050. Data were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 26).

Results

Participant characteristics

In total, 236 participants were included in the analysis. Participant characteristics are shown in . In summary, the mean age was 62.8 (standard deviation 11.3) years, with the majority male (56%) and of White ethnic background (97%). Over half of respondents were self-reported transplant recipients (51%), with the other 49% made up of those with non-dialysis CKD; 4% of respondents had received a positive COVID-19 test.

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

Most frequently accessed sources for COVID-19 information

Overall, 6% (n = 13) participants reported they had never sought information about COVID-19, whilst 3% (n = 8) sought information several times a day. shows the frequency in the access of different sources for COVID-19 information. The most frequently accessed source of health information was television/radio news (a mean score of 4.3 with only 4% indicating they never accessed information via this source); 13% of respondents reported accessing COVID-19 information several times a day from television/radio news. Other frequently accessed sources of information were official government press releases (4.0), medical institution press releases (3.8), consultation with healthcare staff (3.4), and conversations with family and friends (3.4). The least frequently accessed source of health information were celebrities and social media influencers (mean score 1.3 with 83% selecting “Never”) and social media (1.7 and 67% selecting “Never”).

Table 2. How often do you access the following sources of information about COVID-19?

Most trusted sources for COVID-19 information

shows the trust in these different COVID-19 information sources. The most trusted source of information about COVID-19 was consultation with healthcare staff (mean score 6.1). Other trusted sources were medical institution press releases (5.9) and official government press releases (5.3). The least trusted sources were celebrities and social media influencers (mean score 1.7 and 65% saying they had very little trust) and social media (1.8, 59% having very little trust).

Table 3. How much do you trust the following sources of information about COVID-19?

There were positive correlations between access and trust in all information sources (rs = .383 to .608, all significant p < .001), that is, a greater trust in a source was associated with more frequent access. The only exception was consultation with healthcare staff where trust was not associated with access (r = .126, p = .060).

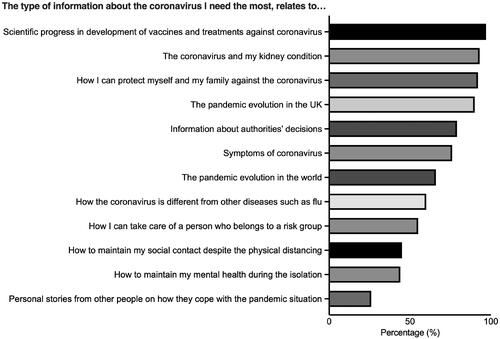

Most sought information about COVID-19

shows respondents’ most sought information about COVID-19. The most sought information regarded the scientific progress in development of vaccines and treatments against coronavirus (97%), how coronavirus affected those with a kidney condition (93%), and how respondents could protect themselves and their families against the coronavirus (92%). The least sought information concerned people’s personal stories (26%) and mental health (44%).

Association between information source, and anxiety and depression

Less frequent access of information from newspapers (β = −.162, p = .027) was associated with higher anxiety on the DASS-21. More frequent access of information from consultation with healthcare staff was associated with higher depression (β = .190, p = .019), anxiety (β = .207, p = .008) and stress (β = .184, p = .031) on the DASS-21, and a higher anxiety score on the SHAI (β = .308, p < .001). Data shown in .

Table 4. Association between information source access, and anxiety and depression.

Less frequent access of information from official government press releases was associated with higher anxiety on the DASS-21 (β = −.229, p = .013) and higher anxiety on the SHAI (β = −.266, p = .005). Less trust in information from official government press releases was associated with higher depression (β = −.210, p = .031), anxiety (β = −.242, p = .010) and stress (β = −.299, p = .003) on the DASS-21, and higher anxiety on the SHAI (β = −.261, p = .006). Data shown in .

Table 5. Association between information source trust, and anxiety and depression.

Factors predicting health information access and trust

Age

Increased age was associated with a lower likelihood in accessing information from social media (−0.043, p = .002), and from celebrities and social media influencers (−0.048, p = .007). Trust was greater in information from television/radio news (0.034, p = .005) and from consultation with healthcare staff (0.039, p = .002) as age increased.

Ethnicity

Trust in information from celebrities and social media influencers (1.854, p = .030) was greater in those from an Asian ethnicity.

Education

Those without further education after high school were less likely to access information from television/radio news (−1.025, p = .003), other television/radio programmes (−0.892, p = .011), newspapers (−0.899, p = .014), and websites or online news pages (−1.027, p = .004). Those without any formal education were more likely to get information from conversations with friends and family (2.028, p = .006) and healthcare staff (1.578, p = .034), as well as from medical institution press releases (1.521, p = .040). Those with college education were more likely to access information from social media (1.312, p < .001) and celebrities and social media influencers (1.682, p = .002), and less likely to get information from newspapers (−0.742, p = .019).

Trust in information from television/radio news (−0.811, p = .029), newspapers (−1.245, p = .000), and websites or online newspapers (−0.904, p = .010) was lower in those without further education after high school. In those without a college education, trust was greater in information gained in conversations with family and friends (0.773, p = .011), social media (0.829, p = .015), official government press releases (0.693, p = .023), and celebrities and social media influencers (0.944, p = .037).

Comorbidities

Respondents with one other comorbidity were more likely to access information from conversations with family and friends (1.992, p = .045).

Kidney disease status

Kidney transplant recipients were less likely to trust information from celebrities and social media influencers (−2.315, p = .037).

Discussion

Summary of key findings

Our findings show that news from the television and radio is the most frequently accessed source of information about COVID-19. Other frequently accessed sources include government and medical institution press releases. Information source access was associated with trust, and the most trusted source of COVID-19 information was from consultation with healthcare staff. Social media was the least accessed and trusted source of COVID-19 information. Most patients sought information regarding COVID-19 treatments as well as how COVID-19 affects their kidney condition. Higher anxiety, stress and depression were associated with less access and trust in official government press releases. Education status had a large influence on information trust and access with lower education level associated with greater access and trust in social media and away from traditional media platforms.

Interpretation of findings

Although not necessarily the most trusted source of COVID-19 information, traditional news media (e.g. television and radio) was the most frequently accessed source of information in those living with a kidney condition. In the general population, a previous study has shown that news organizations have remained the single most widely used source of information about COVID-19 throughout the pandemicCitation21. Somewhat reassuringly, other frequently accessed sources include government and medical institution press releases. Trust in government, scientists and health professionals is seen as essential in preventing the spread of COVID-19Citation22 and implementing a successful vaccine programme in the UKCitation23.

Whilst news organizations have played an important role in helping people navigate the COVID-19 infodemic by providing brief yet formal information, it must be noted that there are limits with information inequality as news media can struggle to reach and effectively serve many groups, such as younger people, those with lower levels of education, and often many disadvantaged or marginalized communities. Distrust in traditional news media can also lead to selective exposure to newsCitation24 and increases the use of alternative sources, such as digital media. We found that those without further education after high school were less likely to access information from sources such as television/radio news and newspapers, and often relied on social media for information.

We found that trust in “websites or online news pages” was poor, with almost a third of respondents never accessing information from these sources. This is in contrast to other studies where the internet has been shown to be a primary health information channel for the general public during COVID-19Citation25. However, these contrasting findings could be due to differences in location, stage of pandemic and phrasing of questioning. Furthermore, it has been well established that the internet can be a significant source of COVID-19 misinformation and poor quality reportingCitation26. The promotion of reliable information sources on the internet, particularly those which are kidney specific, may help in engagement amongst those living with kidney disease. Our findings showed that social media was the least accessed and trusted source of information on COVID-19. As discussed, misinformation on COVID-19 is widespreadCitation26, but especially on social mediaCitation27,Citation28. Social media may have a more direct, personal impact on assessments of risk and a study by Nielson et al.Citation21 found that greater use of digital platforms – including social media – was associated with higher belief in vaccine misinformation. It is well understood that younger people are more likely to rely on various digital platforms, especially social media, for news and informationCitation29, and in support of this we found increased age was associated with a lower likelihood in accessing information from social media. Systematic monitoring of the circulation of misinformation on social media is necessary to counter potential misinformationCitation30.

Unsurprisingly, more frequent access of an information source was positively associated with greater trust in it. The most trusted source of COVID-19 information was from consultation with healthcare staff; although interestingly, trust in this information was not associated with more frequent access. This is likely as access to healthcare staff, for example, through clinic appointments, has been severely reduced during the pandemic. Nonetheless, patients, especially those older and more comorbid, may receive greater exposure to COVID-19 information from healthcare staff during regular visits for their existing conditions. This may explain why we found that more frequent access of information from consultation with healthcare staff was associated with higher depression, anxiety and stress.

Those living with a kidney condition are at greater risk of mental health disordersCitation11, including depression and anxiety. Numerous studies have demonstrated that COVID-19 has resulted in increased levels of depression, anxiety and distressCitation3,Citation8,Citation9, including in those with CKD and on dialysisCitation10. Psychological distress may impede a person’s ability to cope with the many life changes COVID-19 has requiredCitation14. We found that access and trust in information sources could explain some of the variance in depression and anxiety scores observed. Notably, higher anxiety, stress and depression were associated with less access and trust in official government press releases. This result is unsurprising given that in the UK the widely broadcasted official government press conferences, conducted by the Prime Minister and senior public health figures, have been used as the principal means of all important COVID-19 updates and restriction announcements.

We found that less frequent access of information from newspapers was associated with higher anxiety. Similar findings have been reported by De Coninck et al.Citation15 where greater exposure to traditional media (television, radio, newspapers) was associated with lower conspiracy and misinformation beliefs. In a study by Bendau et al.Citation12, greater frequency, duration and diversity of media exposure were positively associated with more symptoms of depression, and unspecific and COVID-19 specific anxiety. Moderate symptoms of (un)specific anxiety and depression occurred at a critical threshold of seven times per day and 2.5 h of media exposure. The usage of social media was associated with more pronounced psychological strain. Of course, it must be noted that these relationships may be bi-directional, that is, those with pre-existing anxiety and depression may avoid media and news coverage of COVID-19.

We found that education status had a large influence across a diverse range of information source trust and access. Our data showed that lower education level was generally associated with more frequent access and greater trust in social media and away from traditional media platforms (e.g. newspapers). A report by Neilsen et al.Citation21 found similar findings whereby news organizations were consistently more widely used by those with higher levels of education, and social media was more widely used by those with low levels of education. Given the reported problems with the information from social media, these results are concerning, and it appears that inequalities in news use around the pandemic seem aligned with pre-existing inequalities around factors such as socioeconomic status and educationCitation31.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess how kidney patients have accessed a diverse range of COVID-19 information sources, and how this has potentially impacted upon mental health. Our study is strengthened by the use of established validated questionnaires to assess anxiety, stress and depression. We also used questions, regarding information sources, adapted from the WHO “behavioural insights on COVID-19” survey. Nonetheless, our findings should be viewed in line with its limitations. Whilst our sample was divided evenly into transplant recipients and those with non-dialysis CKD, the sample contained a relatively homogeneous group of patients (e.g. older, White ethnicity). We did not include patients receiving renal replacement therapy – a group at greater risk of both COVID-19 and mental health problems. There was a relatively low response rate to our survey (approximately 10%) potentially introducing a selection bias into the sample. This study was created to obtain information that could be used to inform rapid evidence synthesis on the COVID-19 pandemic and potentially be used to aid the development of patient and healthcare professional resources. As such, no formal sample size was performed. Due to the pandemic, the study was conducted entirely online. Online samples inevitably under-represent people who are not online (typically older, less affluent, and with limited formal education)Citation32 and our sample may over-represent those who obtain their health information using online or digital means. The nature of the questions may also introduce elements of social desirability bias into our findings. The cross-sectional nature of our study makes it difficult to make casual interferences and is limited in the ever-changing COVID-19 landscape. Further, we were unable to collect data pertaining to personality or psychosocial support which may influence how people may access or perceive information sources.

Conclusion

Our findings show that traditional forms of media remain a popular source of health information in those living with kidney conditions. Despite an absence of regular access, interactions with healthcare professionals are the most trusted source of health information. In an ever-growing digital environment, we found that social media was deemed untrustworthy for COVID-19 information and infrequently accessed. Those using this to disseminate health-related information should be cautious in its use. Those who did not frequently access information from government press releases had higher depression, stress and anxiety, suggesting that kidney patients should be advised to access this information regularly. Whether these findings are specific to people with kidney diseases is unclear; however, overall our results provide some evidence for problematical associations of COVID-19 related information exposure with psychological distress and could serve as an emphasis for recommendations.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This work was supported by the Stoneygate Trust, NIHR Leicester Biomedical Research Centre, and NIHR Applied Research Collaboration (ARC) East Midlands.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

CMRO peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

Conception or design, or analysis and interpretation of data, or both: T.J.W., J.P. Drafting the article or revising it: all authors. Providing intellectual content of critical importance to the work described: T.J.W., C.J.L., A.C.S. Final approval of the version to be published: all authors.

Acknowledgements

This report is independent research supported by the National Institute for Health Research Leicester Biomedical Research Centre and the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration East Midlands (ARC-EM). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the Stoneygate Trust, NHS, National Institute for Health Research Leicester BRC, ARC-EM or the Department of Health. We are grateful to all the participants who took part in the studies and other researchers who assisted with data collection. Studies in which data are presented were funded by National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration East Midlands and the Stoneygate Trust, and supported by the NIHR Leicester Biomedical Research Centre.

Data availability statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- Rombolà G, Brunini F. COVID-19 and dialysis: why we should be worried. J Nephrol. 2020;33(3):401–403.

- Flythe JE, Assimon MM, Tugman MJ, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of individuals with pre-existing kidney disease and COVID-19 admitted to intensive care units in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2021;77(2):190–203.

- Chan ASW, Ho JMC, Li JSF, et al. Impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on psychological well-being of older chronic kidney disease patients. Front Med. 2021;8:666973.

- Council E-E, Group EW. Chronic kidney disease is a key risk factor for severe COVID-19: a call to action by the ERA-EDTA. Nephrol Dialysis Transpl. 2020;36(1):87–94.

- Naeem SB, Bhatti R. The covid-19 ‘infodemic’: a new front for information professionals. Health Info Libr J. 2020;37(3):233–239.

- Tsfati Y, Cohen J. Perceptions of Media and Media Effects. The International Encyclopedia of Media Studies. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444361506.wbiems995

- Glik DC. Risk communication for public health emergencies. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:33–54.

- Jia R, Ayling K, Chalder T, et al. Mental health in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic: cross-sectional analyses from a community cohort study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(9):e040620.

- Salari N, Hosseinian-Far A, Jalali R, et al. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Global Health. 2020;16(1):57.

- Lee J, Steel J, Roumelioti M-E, et al. Psychosocial impact of COVID-19 pandemic on patients with end-stage kidney disease on hemodialysis. Kidney360. 2020;1(12):1390–1397.

- Simões ESAC, Miranda AS, Rocha NP, et al. Neuropsychiatric disorders in chronic kidney disease. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10(932):932.

- Bendau A, Petzold MB, Pyrkosch L, et al. Associations between COVID-19 related media consumption and symptoms of anxiety, depression and COVID-19 related fear in the general population in Germany. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2021;271(2):283–291.

- Shabahang R, Aruguete MS, McCutcheon LE. Online health information utilization and online news exposure as predictor of COVID-19 anxiety. N Am J Psychol. 2020;22(3):469–482.

- Stainback K, Hearne BN, Trieu MM. COVID-19 and the 24/7 news cycle: does COVID-19 news exposure affect mental health? Socius. 2020;6:237802312096933.

- De Coninck D, Frissen T, Matthijs K, et al. Beliefs in conspiracy theories and misinformation about COVID-19: comparative perspectives on the role of anxiety, depression and exposure to and trust in information sources. Front Psychol. 2021;12:646394.

- Ko NY, Lu WH, Chen YL, et al. COVID-19-related information sources and psychological well-being: an online survey study in Taiwan. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:153–154.

- Osman A, Wong JL, Bagge CL, et al. The depression anxiety stress scales-21 (DASS-21): further examination of dimensions, scale reliability, and correlates. J Clin Psychol. 2012;68(12):1322–1338.

- Wang C, Chudzicka-Czupała A, Tee ML, et al. A chain mediation model on COVID-19 symptoms and mental health outcomes in Americans, Asians and Europeans. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):6412–6481.

- Alberts NM, Hadjistavropoulos HD, Jones SL, et al. The Short Health Anxiety Inventory: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Anxiety Disord. 2013;27(1):68–78.

- Salkovskis PM, Rimes KA, Warwick HM, et al. The health anxiety inventory: development and validation of scales for the measurement of health anxiety and hypochondriasis. Psychol Med. 2002;32(5):843–853.

- Nielsen RK, Fletcher R, Newman N, et al. Navigating the ‘infodemic’: how people in six countries access and rate news and information about coronavirus. Oxford, UK: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism; 2020.

- Han Q, Zheng B, Cristea M, et al. Trust in government regarding COVID-19 and its associations with preventive health behaviour and prosocial behaviour during the pandemic: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Psychol Med. 2021;26:1–11.

- Udow-Phillips M, Lantz PM. Trust in public health is essential amid the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(7):431–433.

- Strömbäck J, Tsfati Y, Boomgaarden H, et al. News media trust and its impact on media use: toward a framework for future research. Ann Int Communic Assoc. 2020;44(2):139–156.

- Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Env Res Public Health. 2020;17(5):1729.

- Cuan-Baltazar JY, Muñoz-Perez MJ, Robledo-Vega C, et al. Misinformation of COVID-19 on the internet: infodemiology study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(2):e18444.

- Swire-Thompson B, Ecker UKH, Lewandowsky S, et al. They might be a liar but they’re my liar: source evaluation and the prevalence of misinformation. Political Psychology. 2020;41(1):21–34.

- Chou WS, Oh A, Klein WMP. Addressing health-related misinformation on social media. JAMA. 2018;320(23):2417–2418.

- Chou WY, Hunt YM, Beckjord EB, et al. Social media use in the United States: implications for health communication. J Med Internet Res. 2009;11(4):e48.

- Lockyer B, Islam S, Rahman A, et al. Understanding COVID-19 misinformation and vaccine hesitancy in context: findings from a qualitative study involving citizens in Bradford, UK. Health Expect. 2021;24(4):1158–1167.

- Fletcher R, Kalogeropoulos A, Simon FM, et al. Information inequality in the UK coronavirus communications crisis [Internet]. Oxford (UK): Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism; 2020 [cited 2021 Jul]. Available from: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/information-inequality-uk-coronavirus-communications-crisis

- Donkin L, Glozier N. Motivators and motivations to persist with online psychological interventions: a qualitative study of treatment completers. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(3):e91.