Abstract

Objective

To compare treatment patterns of United States (US) veterans stable on innovator infliximab (IFX) who switched to an IFX biosimilar (switchers) or remained on innovator IFX (continuers).

Methods

US Veterans Healthcare Administration data (01/2012–12/2019) were used to identify adults with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), psoriatic arthritis (PsA), plaque psoriasis (PsO), ankylosing spondylitis (AS), or Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis (i.e. inflammatory bowel disease [IBD]), treated with innovator or biosimilar IFX. Index date was the first IFX biosimilar administration for switchers or a random innovator IFX administration for continuers. Patients were required to have ≥5 innovator IFX administrations during the 12 months pre-index (prevalent population). Patients with ≥12 months of observation prior to the first innovator IFX administration were analyzed as the primary population (incident population), and data were assessed from start of innovator IFX. Inverse probability of treatment weighting was used to balance baseline characteristics between cohorts. Treatment patterns were evaluated post-index; continuers were censored before switching to IFX biosimilar. Discontinuation was defined as switching to another biologic (including innovator IFX) or having ≥120 days between 2 consecutive index treatment records.

Results

In the incident population, mean [median] duration of follow-up was 737 [796] days among switchers (N = 838) and 479 [337] days among continuers (N = 849). Compared to continuers, switchers were 2.88-times more likely to discontinue index therapy (hazard ratio [HR] = 2.88, p < .001) and 4.99-times more likely to switch to another innovator biologic (HR = 4.99, p < .001). Of 653 switchers switching to another innovator biologic, 594 (91.0%) switched back to innovator IFX. Results were similar among the prevalent population and RA and IBD subgroups.

Conclusion

Patients switching from innovator to biosimilar IFX were more likely to discontinue treatment and switch to another innovator biologic (notably back to innovator IFX) than those remaining on innovator IFX; however, reasons for discontinuation and switching are unknown.

Introduction

Chronic inflammatory diseases (CIDs) include conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), psoriatic arthritis (PsA), plaque psoriasis (PsO), ankylosing spondylitis (AS), Crohn's disease (CD), and ulcerative colitis (UC)Citation1. The prevalence of CIDs differs according to each condition, with approximately 1.28–1.36 million patients affected with RA, 910,000 affected with UC, and 785,000 affected with CD in the United States (US)Citation2,Citation3. These conditions can have serious detrimental effects on quality of life and health outcomes, in particular because they are chronic conditions with associated comorbiditiesCitation1,Citation4.

Despite the significant disease burden, treatment with biologic agents has markedly improved the outcome of the management of CIDsCitation4,Citation5. Among biologic agents, infliximab was initially approved for the treatment of CD in the US by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1998 (Remicade (infliximab), referred to herein as “innovator infliximab” or “IFX”) and is currently indicated for a variety of other CIDs, including RA, PsA, PsO, AS, and UCCitation6,Citation7. Biosimilars of IFX are products that are highly similar to innovator IFX, with no clinically meaningful differences in quality, biological activity, safety or efficacyCitation8–10, and are now also available for the treatment of CIDs in the US. The first IFX biosimilar (IFX-dyyb, CT-P13, Inflectra, registered trademark of Hospira UK, a Pfizer company) was approved on April 5, 2016 and became available for use in clinical practice on November 28, 2016Citation11. As of August 2019, four IFX biosimilars have been approved, though IFX-dyyb, IFX-abda (SB2, Renflexis, registered trademark of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp), and IFX-axxq (ABP 710, Avsola, registered trademark of Amgen Inc.) are the only three commercially available in the USCitation12–15.

Switching from innovator biologics to biosimilars remains a topic of scientific interestCitation16. Changing therapies for reasons unrelated to effectiveness and tolerability, such as cost, either between molecules (e.g. innovator tumor necrosis factor inhibitor [TNFi] to innovator TNFi) or, in this case, between two versions of the same TNFi (innovator and biosimilar) is known as non-medical switching (NMS). Characterization of NMS involving an innovator and biosimilar presents an opportunity to better understand emerging treatment patterns involving the innovator biologic and biosimilar. While randomized controlled trials have shown comparable efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity among patients switching between IFX biosimilars and innovator IFXCitation17,Citation18, results from real-world studies have suggested that NMS leads to increased rates of treatment discontinuation and switching to yet another therapy, including back to innovator IFXCitation19–23. However, reasons for discontinuation are often not provided and therefore conclusions regarding efficacy and safety cannot be drawn. One potential reason frequently cited in the literature is the “nocebo” effect, whereby the patient has a negative subjective feeling towards the biosimilar that then adversely influences non-clinical outcomes such as medication persistence, switching, healthcare resource utilization, and costs, highlighting the need for mitigation measures to ensure a smooth transition to the biosimilarCitation22,Citation24–26.

The medication utilization patterns of patients stable on innovator IFX switching to an IFX biosimilar in the US are not well documented. Specifically, rates of treatment switching and discontinuation after an initial switch to an IFX biosimilar have not been thoroughly studied in clinical practice in the US. One recent study using US claims data identified that patients who switch from innovator to biosimilar IFX were more likely to switch to another innovator biologic, often back to the innovator IFX, or discontinue treatment, as compared to patients who do remain on innovator IFXCitation27. To add to the real-world evidence in a different population, the current study evaluated US veterans with CID treated with innovator IFX who received care through the US Veterans Healthcare Administration (VHA). The VHA data source is uniquely situated to evaluate this study question as the Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare system’s national formulary had previously included innovator IFX as well as IFX-dyyb. In September 2018, both therapies were removed and replaced on the formulary with IFX-abda, resulting in IFX-abda being the only IFX product on the formularyCitation28. Both formulary changes allowed veterans to remain on their current IFX if they were previously on treatment. New initiators were directed to use the biosimilar product, though requests could be made if a physician wanted to use a non-formulary IFX drug. Using data from the VHA therefore allowed the current study to assess changes in medication utilization patterns within a health system undergoing adoption of IFX biosimilars. The goal of this study was to assess treatment patterns after switching to any IFX biosimilar, and the methods were designed to compare groups of switchers and continuers; this study did not aim to assess the impact of a specific formulary change. Therefore, the objective of this study was to characterize and compare patterns of discontinuation and switching within the VHA database among patients with CIDs stable on innovator IFX who switched to an IFX biosimilar versus those remaining on innovator IFX. Additionally, subgroups of patients with RA and IBD were evaluated to identify any condition-specific differences in treatment patterns.

Methods

Data source

Data from January 1, 2012 to December 31, 2019 (study period) from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) were used to address the study objectives. The VHA is the single largest integrated healthcare delivery system in the US, providing care at 1250 health care facilities to over 9 million military veterans enrolled in the VA health care program. It provides comprehensive services, including primary, specialty and inpatient care, rehabilitation, long-term and home care, and other services to veterans. The VA CDW contains information on all outpatient visits, hospital stays, treatments, prescriptions, and lab results as well as billing and benefits information. The CDW is updated daily to weekly, so there is little to no lag time. The VA CDW stores data in separate databases, one for each type of clinical information. Each patient in the system has a unique patient identifier to allow for longitudinal follow up as well as to cross reference to the various separate databases. The data were de-identified and complied with HIPAA, and the study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the White River Junction VA Medical Center in White River Junction, Vermont, and was granted an exemption for consent because it was deemed impractical to require consent for this minimal risk exposure.

Study design

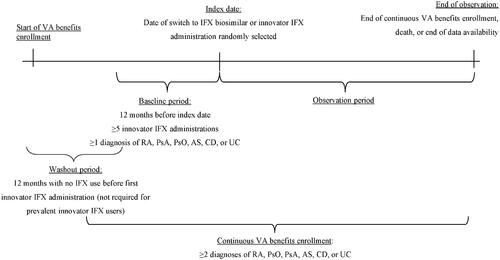

A retrospective cohort study design was used to compare patients stable on innovator IFX switching to an IFX biosimilar (i.e. switchers) and those remaining on innovator IFX (i.e. continuers) (). Stability on innovator IFX was defined as having ≥5 visits for innovator IFX administrations in the 12 months before the index date, referred to as the baseline period.

Figure 1. Study design. Abbreviations. AS: ankylosing spondylitis; CD: Crohn's disease; IFX: infliximab; PsA: psoriatic arthritis; PsO: plaque psoriasis; RA: rheumatoid arthritis; UC: ulcerative colitis; VA: Veteran's Affairs.

For switchers, the index date was defined as the date of the first visit for an IFX biosimilar administration on or after January 1, 2012. For continuers, a random index date was selected among all visits for innovator IFX administrations starting from the 6th administration to the last one (i.e. following stabilization). A patient qualifying for the continuer arm could, if switched to a biosimilar after the index date, also qualify for the switch arm. Based on this design, a single patient could contribute to both cohorts; i.e. once as a continuer (using the time before the switch to an IFX biosimilar) and once as a switcher (starting from the moment the patient switched to an IFX biosimilar), following the methodology described by Lund et al.Citation29 By allowing patients who eventually switched to an IFX biosimilar to contribute to the continuers cohort, an unbiased cohort of continuers that is representative of the real-world use of innovator IFX was obtained.

The observation period spanned from the index date up to the earliest of disenrollment, end of data availability, or death. For patients included in both cohorts, the observation period for time spent in the continuers cohort started at the randomized index date and was censored at the day before the switch to an IFX biosimilar; the observation period for time spent in the switchers cohort then started from the day of the switch to an IFX biosimilar (index date for switchers).

Patient selection

To be included in the study, patients were required to have ≥2 visits with a diagnosis for either RA (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9 CM] code 714.0 or 714.2; International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10 CM] codes M05.1-M05.9, or M06), PsA (ICD-9 CM code 696.0; ICD-10 CM code L40.5x or M07.3x), PsO (ICD-9 CM code 696.1; ICD-10 CM codes L40.0-L40.4, L40.8, or L40.9), AS (ICD-9 CM code 720.0; ICD-10 CM code M45.x), CD (ICD-9 CM code 555.x; ICD-10 CM code K50.x), or UC (ICD-9 CM code 556.x; ICD-10 CM code K51.x), including ≥1 visit in the 12-month baseline period, and ≥1 visit for an administration of innovator IFX or IFX biosimilar on or after January 1, 2012. Patients were also required to have ≥5 visits for innovator IFX administrations during the 12-month baseline period, have ≥12 months of continuous clinical activity before the index date, and be ≥18 years of age at the index date.

Excluded were patients with a previous transplant procedure during the baseline period, diagnosis of pregnancy (ICD-9 CM code V22.x; ICD-10 CM codes Z33.x or Z34.x) during the baseline period, diagnosis of heart failure (ICD-9-CM code 428.x; ICD-10-CM code I50.x) during the baseline period, ≥1 administration for innovator IFX and an IFX biosimilar on the index date (for switchers only), or ≥1 record for a biologic agent other than innovator IFX between the first innovator IFX administration during the baseline period and the index date.

Patients selected based on these criteria were termed the “prevalent” population. This population maximized the sample size and all available data at the time by including both long-term users and shorter-term users who initiated innovator IFX during the study period. However, since long-term users entered the database already on treatment with innovator IFX, the date of initiation and exact duration of treatment could not be determined and appropriately adjusted for. An “incident” population was therefore identified by selecting the subset of prevalent patients with ≥12 months of continuous clinical activity without any innovator IFX administrations prior to the first innovator IFX administration (i.e. patients newly stabilized on innovator IFX). While the known date of initiation of these patients allowed the analysis to appropriately adjust for the duration of treatment on innovator IFX prior to the index date, this additional criterion resulted in a smaller sample size and the inclusion of more recent initiators of innovator IFX only. Given the ability to identify the date of initiation of innovator IFX and to adjust for the duration of treatment on innovator IFX, the primary population of interest for this study was the incident population. For a full description of sample selection, see .

Figure 2. Patient selection. Abbreviations. AS: ankylosing spondylitis; CD: Crohn's disease; ICD-9-CM/ICD-10-CM: International Classification of Disease, Ninth/Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification; IFX: infliximab; PsA: psoriatic arthritis; PsO: plaque psoriasis; RA: rheumatoid arthritis; UC: ulcerative colitis; VA: Veteran's Affairs. Notes: 1. Diagnosis was identified using the following ICD-9 CM and ICD-10 CM codes: RA (ICD-9 CM code 714.0, 714.2; ICD-10 CM code: M05.1-M05.9, M06.x), PsA (ICD-9 CM code 696.0; ICD-10 CM code: L40.5x, M07.3x), PsO (ICD-9 CM code 696.1; ICD-10 CM code: L40.0-L40.4, L40.8, L40.9), AS (ICD-9 CM code 720.0; ICD-10 CM code: M45.x), CD (ICD-9 CM code 555.x; IDC-10 CM code K50.x), or UC (ICD-9 CM code 556.x; IDC-10 CM code K51.x). 2. Innovator IFX (NDC 57894-030-01 and HCPCS J1745), IFX biosimilar: infliximab-abda (Renflexis, NDC 0006-4305-02 and HCPCS Q5102, Q5104) and infliximab-dyyb (Inflectra, NDC 0069-0809-01 and HCPCS Q5102, Q5103). 3. For patients stable on innovator IFX switching to an IFX biosimilar (i.e. switchers), the index date was defined as the date of IFX biosimilar initiation. For patients remaining on innovator IFX (i.e. continuers), a random index date was selected among all innovator IFX administrations from the 6th administration to the last one (after the 5th administration that defines a patient as stable). 4. Pregnancy was identified using ICD-9 CM code V22.x and ICD-10 CM codes Z33.x and Z34.x. 5. Diagnosis of heart failure was identified using ICD-9-CM code 428.x and ICD-10-CM code I50.x. 6. Continuous clinical activity was defined as ≥2 outpatient, excluding emergency department visits, or inpatient encounters during the 12-month period.

Study outcomes

Discontinuation patterns were measured during the observation period; more specifically, the proportion of patients discontinuing the index therapy and time to discontinuation were described. Discontinuation was defined as either switching to a different innovator biologic agent or having a gap of ≥120 days between 2 consecutive administrations of the index therapy, whichever occurred first. Time to discontinuation was defined as the time in days between the index date and the end of continuous treatment, which was either the date of first switch to another innovator biologic agent or 120 days following the date of the last infusion before a gap ≥120 days in treatment, whichever occurred first.

Switching patterns were measured during the observation period and included the proportion of patients switching to another innovator biologic agent (including innovator IFX), along with the time to switch. Of note, switches between IFX biosimilars could not be detected consistently over the study period, so innovator biologics were the only alternative for switching. In addition, since patients who switched to an IFX biosimilar in the continuers cohort were censored the day before they switched (they started contributing to the switcher cohort on that day), switches to an IFX biosimilar were not counted. This was done in accordance with Lund et al. to avoid conflating the cohortsCitation29. Thus, in the switcher cohort, switches from IFX biosimilar to any biologic, including innovator IFX (but not to another biosimilar IFX), were counted as a switch event. In the continuer cohort, switches from innovator IFX to any other innovator biologic were counted as a switch event. Switches from innovator IFX to biosimilar IFX did not contribute to switch events, as this occurred the day after censoring occurred. Time to switch was defined as the time in days between the index date and the date of the first record for another innovator biologic agent (including innovator IFX).

Statistical analysis

Due to the non-experimental nature of this study, patients in the switcher and continuer groups may have had different observed baseline characteristics. As such, inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) was used to minimize confounding. Propensity scores were estimated using multivariable logistic regression, adjusting for variables with >10% standardized difference between cohorts at baseline. Based on this criteria, the following baseline covariates for the prevalent population were included: index year (2016–2017 vs. 2018–2019), VHA service area (i.e. US region), length of treatment with innovator IFX, and all-cause and CID-related number of IFX visits per month. Propensity score models for the incident population also included the following baseline covariates: diagnosis of diarrhea, Quan-Charlson Comorbidity Index (Quan-CCI) score (a measure of comorbidity burden used to predict a patient’s ten-year mortality risk based on a range of conditions)Citation30, use of adalimumab, use of certolizumab, and number of other CID-related outpatient visits (i.e. outpatient visits not related to IFX administration, ER visits, or telephone calls) per month.

Baseline characteristics and outcomes were described using means, standard deviations (SDs), and medians for continuous variables and frequencies and proportions for categorical variables. Differences in baseline characteristics were assessed using standardized differences, where a standardized difference <10% indicated balance between cohorts. Kaplan-Meier (KM) survival curves were used to compare time to discontinuation of index therapy and time to switch to another innovator biologic agent (including innovator IFX) between switchers and continuers. Log-rank tests and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to compare KM curves at 3- and 6-month intervals, up to 18 months. Hazard ratios (HRs), along with 95% CIs and p-values, were generated using a Cox proportional hazards model.

Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses were conducted among those with ≥1 visit with a diagnosis for RA (RA subgroup) or ≥1 visit with a diagnosis for IBD (i.e. UC and CD; IBD subgroup) during the baseline period. IPTW were re-estimated for all subgroups. All analyses were performed with SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics

Incident population

After IPTW, the weighted incident population included 838 switchers and 849 continuers. Among switchers and continuers, 17.7% and 16.3% had RA, respectively (standardized difference = 3.5%) and 72.5% and 73.1% had IBD, respectively (standardized difference = 1.3%). Mean age was 54.7 (SD = 17.2) years for switchers and 54.9 (SD = 13.4) years for continuers (standardized difference = 0.9%) (). Among switchers and continuers, 10.7% and 11.4% were female, respectively (standardized difference = 2.3%). Mean Quan-CCI score was 0.93 (SD = 1.45) among switchers and 0.93 (SD = 1.16) among continuers (standardized difference = 0.4%). Prior to the index date, patients were treated with innovator IFX for an average of 736 (SD = 494) days for switchers and 729 (SD = 429) days for continuers (standardized difference = 1.4%). Other baseline characteristics were also well-balanced between cohorts (standardized differences <10%), except for three characteristics which narrowly missed the definition of balanced: all-cause number of ER visits per month (standardized difference = 10.3%), CID-related total monthly healthcare costs (standardized difference = 11.6%), all-cause and CID-related pharmacy costs (standardized difference = 11.2% and 12.2%, respectively).

Table 1. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics.

Prevalent population

After IPTW, the weighted prevalent population included 1531 switchers and 1539 continuers (). Baseline characteristics were generally similar to the incident population. Prior to the index date, patients were treated with innovator IFX for an average of ≥1182 (SD = 783) days for switchers and ≥1180 (SD = 654) days for continuers (standardized difference = 0.3%); however, the exact duration of treatment could have been longer, but could not be determined for the prevalent population given that some patients entered the database already on innovator IFX treatment. Other baseline characteristics were also well-balanced between cohorts (standardized differences <10%).

Discontinuation patterns

Incident population

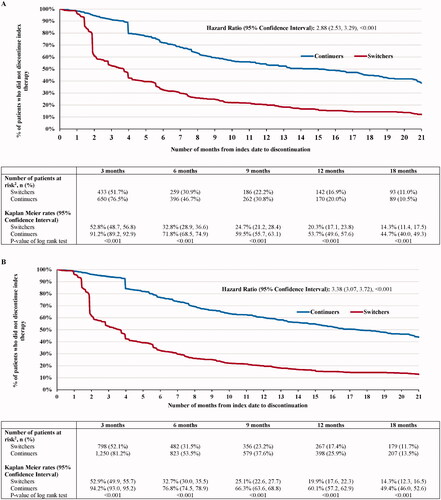

The mean post-index observation period length was 737 (SD = 320) for switchers and 479 (SD = 363) for continuers. The shorter duration of follow-up among continuers was due to the censoring rule that was employed among patients in the continuer group who switched to IFX biosimilar. In the continuers group, 363 (42.8%) patients were censored prior to initiation of an IFX biosimilar, and thus also contributed to the switchers cohort. As of the last follow-up available in the data, 700 (83.5%) switchers and 318 (37.4%) continuers discontinued their index therapy because of a switch or a gap in treatment ≥120 days (HR [95% CI] = 2.88 [2.53, 3.29]; p < .001) (). Among patients who discontinued their index therapy, the mean time to discontinuation was 130 (SD = 144) days for switchers and 208 (SD = 161) days for continuers.

Prevalent population

The prevalent population had similar results to the incident population. Over a mean post-index observation period length of 775 (SD = 293) and 501 (SD = 369) days for switchers and continuers, respectively, 1296 (84.6%) switchers and 543 (35.3%) continuers in the prevalent population discontinued their index therapy because of a switch or a gap in treatment ≥120 days (HR [95% CI] = 3.38 [3.07, 3.72]; p < .001) (). Among patients who discontinued their index therapy, the mean time to discontinuation was 132 (SD = 149) days for switchers and 235 (SD = 173) days for continuers.

Switching patterns

Incident population

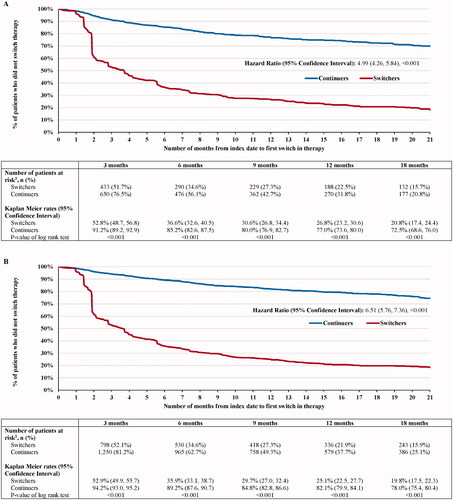

For switchers and continuers, respectively, 653 (77.8%) and 176 (20.7%) switched post-index to another innovator biologic (including innovator IFX) (HR [95% CI] = 4.99 [4.26, 5.84]; p < .001) (). Of note, since switches from one IFX biosimilar to another could not consistently be detected, all alternative treatments for switching were innovator biologics. Among patients who switched to another innovator biologic, the mean time to switch was 129 (SD = 154) days for switchers and 211 (SD = 190) days for continuers. The KM rates representing the proportion of switchers and continuers who did not switch to another innovator biologic were 51.7% and 76.5% at 3 months post-index, 34.6% and 56.1% at 6 months, 22.5% and 31.8% at 12 months, and 15.7% and 20.8% at 18 months, respectively (all log-rank p < .001). As of the last follow-up available in the data, of the 653 switchers who switched to another innovator biologic over the entire duration of the observation period (mean duration = 737 days), 594 (91.0%) switched back to innovator IFX, over a mean time to switch of 117 days (SD = 136), and 59 (9.0%) switched to another innovator biologic. Among the 594 switchers who switched back to innovator IFX, 507 (85.4%) discontinued innovator IFX, of which 476 (80.1%) switched at least one more time prior to the end of all available data, with 427 (71.9%) switching back to an IFX biosimilar and 49 (8.3%) switching to another biologic.

Prevalent population

Similar results were found in the prevalent population. For switchers and continuers in the prevalent population, respectively, 1215 (79.3%) switchers and 272 (17.7%) continuers switched to another innovator biologic (including innovator IFX) (HR [95% CI] = 6.51 [5.76, 7.36]; p < .001) (). Among patients who switched to another innovator biologic, the mean time to switch was 128 (SD = 149) days for switchers and 254 (SD = 218) days for continuers. The KM rates representing the proportion of switchers and continuers who did not switch to another innovator biologic were 52.1% and 81.2% at 3 months post-index, 34.6% and 62.7% at 6 months, 21.9% and 37.7% at 12 months, and 15.9% and 25.1% at 18 months, respectively (all log-rank p < .001). As of the last follow-up available in the data, of the 1215 switchers who switched to another innovator biologic over the entire duration of the observation period (mean duration = 775 days), 1133 (93.3%) switched back to innovator IFX, over a mean time to switch of 120 days (SD = 135), and 82 (6.7%) switched to another innovator biologic. Among the 1133 switchers who switched back to innovator IFX, 976 (86.1%) discontinued innovator IFX, of which 921 (81.3%) switched at least one more time prior to the end of all available data, with 837 (73.9%) switching back to an IFX biosimilar and 84 (7.4%) switching to another biologic.

Subgroup analyses

Replicating analyses within subgroups of patients with RA and IBD yielded similar results as in the main analysis.

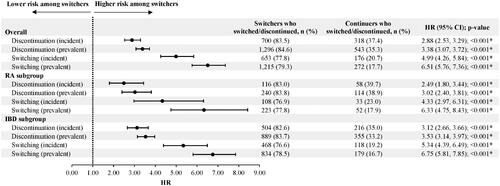

Discontinuation patterns

Among patients with RA in the incident population, after IPTW, there were 139 switchers and 145 continuers. Over a mean post-index observation period length of 769 (SD = 284) and 486 (SD = 379) days for switchers and continuers, respectively, 116 (83.0%) switchers and 58 (39.7%) continuers discontinued their index therapy (HR [95% CI] = 2.49 [1.80, 3.44]; p < .001) (). Similarly, in the prevalent population, after IPTW, there were 286 switchers and 291 continuers. In this population, 240 (83.8%) switchers and 114 (38.9%) continuers discontinued their index therapy during the observation period (HR [95% CI] = 3.02 [2.40, 3.81]; p < .001).

Figure 5. Switching and discontinuation rates for incident (switchers, N = 838; continuers, N = 849) and prevalent (switchers, N = 1531; continuers, N = 1539) patients in the overall population, incident (switchers, N = 139; continuers, N = 145) and prevalent (switchers, N = 286; continuers, N = 291) patients in the RA subgroup, as well as incident (switchers, N = 610; continuers, N = 617) and prevalent (switchers, N = 1062; continuers, N = 1069) patients in the IBD subgroup. Abbreviations. CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; RA, rheumatoid arthritis. Note: *p < .05.

Among patients with IBD in the incident population, after IPTW, there were 610 switchers and 617 continuers. Over a mean post-index observation period length of 713 (SD = 336) and 464 (SD = 362) days for switchers and continuers, respectively, 504 (82.6%) switchers and 216 (35.0%) continuers discontinued their index therapy during the observation period (HR [95% CI] = 3.12 [2.66, 3.66]; p < .001) (). Similarly, among patients with IBD in the prevalent population, after IPTW, there were 1062 switchers and 1069 continuers. In this population, 889 (83.7%) switchers and 355 (33.2%) continuers discontinued their index therapy during the observation period (HR [95% CI] = 3.53 [3.14, 3.97]; p < .001).

Switching patterns

Among patients with RA in the incident population, 108 (76.9%) switchers and 33 (23.0%) continuers switched to another innovator biologic (including innovator IFX) (HR [95% CI] = 4.33 [2.97, 6.31]; p < .001) () as of the last follow-up available in the data. Of the 108 switchers who switched to another innovator biologic, 102 (94.4%) switched back to innovator IFX. In the prevalent population, over a mean post-index observation period length of 800 (SD = 296) and 531 (SD = 384) days for switchers and continuers, respectively, 223 (77.8%) switchers and 52 (17.9%) continuers switched to another innovator biologic (including innovator IFX) (HR [95% CI] = 6.33 [4.75, 8.43]; p < .001). Of the 223 switchers who switched to another innovator biologic, 214 (96.0%) switched back to innovator IFX.

Among patients with IBD in the incident population, 468 (76.6%) switchers and 118 (19.2%) continuers switched to another innovator biologic (including innovator IFX) (HR [95% CI] = 5.34 [4.39, 6.49]; p < .001) (). Of the 468 switchers who switched to another innovator biologic, 426 (91.0%) switched back to innovator IFX. In the prevalent population, over a mean post-index observation period length of 757 (SD = 300) and 487 (SD = 367) days for switchers and continuers, respectively, 834 (78.5%) switchers and 179 (16.7%) continuers switched to another innovator biologic (including innovator IFX) (HR [95% CI] = 6.75 [5.81, 7.85]; p < .001) as of the last follow-up available in the data. Of the 834 switchers who switched to another innovator biologic, 776 (93.0%) switched back to innovator IFX.

Discussion

In this US retrospective cohort study with a mean observation period of over one year, incident patients with CIDs switching from innovator to biosimilar IFX were 2.88-times more likely to discontinue their index therapy compared to those remaining on innovator IFX. A similar finding was observed in the prevalent group, with patients switching from innovator to biosimilar IFX being 3.38-times more likely to discontinue their index therapy. Additionally, both incident and prevalent patients with CIDs switching from innovator to biosimilar IFX were 4-to-6-times more likely to switch to another innovator biologic (including innovator IFX) compared to those remaining on innovator IFX. Among those who were on an IFX biosimilar at index and then switched to another innovator biologic, more than 90% returned to innovator IFX, on average within 4 months. Of those who returned to innovator IFX, more than 70% had another subsequent switch to a biosimilar IFX. Similar switching and discontinuation patterns were observed among the subgroups of patients with RA and IBD.

These three findings, namely that switchers have higher rates of discontinuation and subsequent change in therapy compared to continuers, and that the majority of these subsequent changes in therapy are a return to originator, are all consistent with other published results. In the limited number of real-world studies that compared patients switching from innovator IFX to IFX biosimilar and patients remaining on innovator IFX, the latter patients were more likely to continue with their respective treatmentCitation21,Citation23,Citation26,Citation31–33. For instance, in a French study of patients with RA, AS, or PsA conducted by Scherlinger et al., the drug retention rate was significantly lower in patients who switched to IFX biosimilar (72%) compared to a historic cohort of patients who were treated with innovator IFX (88%; p < .001) Citation23. Regarding the observed increase in subsequent change of therapy, one recent matched-cohort study of a US integrated healthcare system found that a higher proportion of patients with IBD who switched from innovator IFX to IFX biosimilar switched therapy again to another biologic compared to patients who remained on innovator IFX (15.7% versus 11.6%, p < .01)Citation34, corroborating the current findings. Similar findings were reported in a US claims study in both prevalent and incident populations, where a change in therapy was 3.57- and 2.55-times more likely in switchers than continuers, respectively, (p < .001)Citation27. Lastly, several independent studies have also shown that among patients who discontinue an IFX biosimilar, 79% to 92% return to innovator IFXCitation19,Citation22,Citation23,Citation31,Citation35, which is in line with the findings of the current study, where 91.0% to 94.4% switch back to innovator IFX after initially switching to an IFX biosimilar. Interestingly, a number of real-world studies have also evaluated switching between other innovator biologics and their biosimilars, specifically etanercept and adalimumabCitation19–24,Citation31,Citation32,Citation36,Citation37, with results that are consistent with the current analyses, although switching rates varied and reasons for switching back to innovator biologics were often unclear. This highlights the need for further understanding of the policies and measures implemented, to see how they affected switching rates.

While the present study found that patients switching from innovator to biosimilar IFX were more likely to discontinue and to switch again to another innovator biologic, the reasons why are not captured in the VHA database and, thus, remain unclear. One potential reason for switching that has been the focus of several studies is the “nocebo” effectCitation22,Citation24–26. The nocebo effect, which is the negative equivalent of the better-known placebo effect, occurs when a patient has a negative subjective feeling towards a treatment thereby influencing the outcomes negatively. The source of the nocebo effect in the context of biosimilars may be related to a lack of confidence in or understanding of the product, prompting patients to react to perceived minor adverse events or to discontinue treatmentCitation24,Citation25. This effect seems to be intensified when the switch is mandatoryCitation26. To this effect, in the survey-based study of US patients with CIDs by Teeple et al., 85% of patients were concerned that biosimilars would not treat their disease as well as the innovator biologicCitation38. Additionally, several observational studies have reported patients discontinuing biosimilars despite no change in disease activity and/or a lack of objective adverse events, suggesting subjective reasons for treatment discontinuationCitation19,Citation22,Citation23,Citation39,Citation40. These reasons may include differences in product formulation and delivery device, administrative reasons, such as cost, and treatment settingCitation41.

While these reasons may contribute to the increased rates of discontinuation and switching, they likely do not explain them completely. It is possible that switches away from biosimilars may be a reflection of innovator and biosimilar product availability, which has evolved over the past few years, especially within the VA system. The VA healthcare system’s national formulary had previously included innovator IFX and in May 2017, added IFX-dyyb. However, both therapies were removed and replaced on the formulary with IFX-abda on September 2018Citation28. It is important to note that patients who were being treated with innovator IFX or IFX-dyyb were not automatically converted to IFX-abda without approval by the treating provider, although all new starts to IFX were to be prescribed IFX-abda. However, as noted previously, non-formulary requests are permitted in the VA, and non-formulary medications are regulated by the Pharmacy and Therapeutics committee at each VA medical center and not at a national level.

While it seems likely that differences in IFX availability help to explain the medication utilization patterns we observed in this study, we cannot say for certain to what degree these impacted the results, as there is a lack of visibility into the decision-making process at each VA facility regarding use of non-formulary products. A cross-sectional analysis of IFX infusions at two different medical centers found greater uptake of biosimilar IFX at a VA medical center compared to a nearby academic centerCitation42. Another recent study examining biosimilar IFX uptake among patients with UC and CD treated within the VHA system found that adoption of IFX-abda was faster than IFX-dyybCitation28. Indeed, though the current study was unable to differentiate between IFX-abda and IFX-dyyb specifically, the rapid uptake of biosimilar IFX was exhibited in the current study, with 43-47% of patients in the continuers cohort eventually switching to IFX biosimilar (and thus were censored). Some studies have found high use of other non-formulary medications across VA facilitiesCitation43–45. As exhibited in the current study, 90% patients who switched to an IFX biosimilar eventually switched back to innovator IFX, and most of those eventually returned to a biosimilar, although whether it was the same biosimilar cannot be known. Johnson et al., which evaluated uptake of formulary preferred IFX vs non-formulary IFX, found that non-formulary use of IFX innovator was more prevalent among IFX-experienced patients than IFX-naïve patients and that the uptake to formulary preferred IFX was slower in 2017, when IFX-dyyb was first preferred over IFX innovator, than in 2018/19, when IFX-abda was preferred over IFX-dyyb, suggesting that adherence to the VA formulary has improved over time. In any case, in our study the majority of patients remained on IFX, either innovator or biosimilar, and did not switch to another innovator biologic at the end of their follow up, suggesting these were NMS-type changes not due to clinical outcomes.

While the current study found higher rates of discontinuation and switching among patients who switched from IFX innovator to biosimilar compared to patients maintained on innovator IFX, the finding of generally high rates of discontinuation and switching in both cohorts warrant discussion. As noted above, it seems reasonable to attribute these high rates of discontinuing treatment and (multiple) switching in this study – at least in part – to the two formulary changes which were implemented during the observation period of the study. This is noteworthy because the literature has found that, for patients who are switched from one product to another multiple times, the risk for negative health outcomes increases, including adverse events and the loss of efficacyCitation46. In three studies that evaluated outcomes after the switch back to innovator IFX, 71%–100% of patients who reinitiated innovator IFX after discontinuing IFX biosimilar due to disease relapse, lack of treatment efficacy, or adverse events subsequently achieved partial or full clinical improvement after the switch backCitation20,Citation23,Citation47. The proportion of patients not regaining a clinical response suggests that switching itself may be an issue, as opposed to its direction. Interestingly, Pernes et al. evaluated the reasons for discontinuation in a small group of patients at the VA and concluded switching appeared relatively safe among stable patients with IBD. However, they did not report several important details of the study, among them how long patients had been on IFX at the time of the switch, and selected only stable patients for switching, so this outcome is difficult to evaluate comprehensivelyCitation48. Ultimately, the potential short- and long-term health outcomes of multiple switching events remain largely unknownCitation46 and merit further study.

In addition to health outcomes, the impact of switching on healthcare systems and costs must be considered, including both drug and non-drug costs. Past experience with biosimilar introduction in European countries has demonstrated that strategies and implementation of specific policies and practices for biosimilar use may streamline the switching process for healthcare systems and patientsCitation49. Additionally, well-planned implementation of biosimilars can result in increased biologic usage with a concomitant reduction in drug costsCitation50, and there is further potential to use these cost savings to increase patient access to therapyCitation51. However, successful uptake of biosimilars is contingent on a balance of optimal pricing reductions and usage-enhancing policies, as well as costs of implementing the switch, education programs and other mitigation measures to address concerns among both physicians and patientsCitation52, including communication with patients about NMS and reasonable expectations after switchingCitation26. As such, the lower drug costs of IFX biosimilars may be offset by additional costs related to implementation of new treatments and dose adjustments when switchingCitation53. For instance, many sites implement mitigation measures to facilitate the transition between innovators and biosimilars or between biosimilars, in particular to avoid the nocebo effect, but often do not consider the costs of these measuresCitation34,Citation54. Indeed, higher healthcare resource utilization and costs have been reported in studies of real-world switches from innovator biologics to biosimilarsCitation32,Citation55,Citation56. Moreover, a systematic literature review conducted in 2018 found increased healthcare resource use among patients with biosimilar NMSCitation55. As the drug costs of innovator biologics continue to decrease and approach the costs of biosimilarsCitation57,Citation58,Citation59, overall cost savings associated with switching may also decrease in light of the upfront non-drug costs required for implementation of the switch program (e.g. staff training, administrative costs), mitigation measures to prepare patients and prescribers for NMS, and post-switching expenditures related to monitoring and dose adjustmentsCitation55. Though additional real-world studies are necessary to fully quantify the short- and long-term economic impact of NMS in the US, the switching and discontinuation trends observed in the literature support the findings of the current study and suggest the need for careful consideration prior to switching patients from innovator to biosimilar IFX.

A notable strength of this study is the evaluation of both prevalent (i.e. patients stable on innovator IFX for an extended period of time, with mean duration of pre-index innovator IFX treatment of at least 1180–1182 days) and incident patients (i.e. patients newly stabilized on innovator IFX, with mean duration of pre-index innovator IFX treatment of 729–736 days). While results were similar between the two patient populations, the effect of switching to an IFX biosimilar was slightly smaller in the incident population. This may be due to the smaller sample size of the incident population (N = 838 switchers, N = 849 continuers) compared to the prevalent population (N = 1531 switchers, N = 1539 continuers). However, additional research is needed to further evaluate the differences between patients newly stabilized on innovator IFX and those who have maintained long-term stability.

In addition to evaluating switching patterns among patients with CIDs, the present study also assessed subgroups of patients with RA or IBD. The subgroup analyses yielded similar findings as the main analysis, suggesting that the switching and discontinuation patterns observed are consistent regardless of CID indication. These RA- and IBD-specific results contribute important insight to the literature regarding two of the most common CIDsCitation60, which had thus far been frequently evaluated in combination with other IFX indications in studies of switching and discontinuation patternsCitation19–22,Citation32.

Limitations

This study is subject to limitations that are inherent to observational and retrospective analyses. First, the use of this database means caveats such as data omission or coding errors apply. Additionally, the treatment patterns were analyzed based on dispensings of medications, which does not necessarily guarantee the actual consumption of the medication by patients. Furthermore, as with all studies of this nature, results may be confounded due to unobserved factors not accounted for in the propensity score models, leading to residual confounding.

Another limitation of this study is the difference in length of follow-up between the continuers (mean 479 days) and switchers (mean 737 days), which was likely an effect of the censoring rule employed in the continuers cohort. Selection bias due to loss to follow-up (i.e. informative censoring) can threaten the validity of the study resultsCitation61. However, since the mean time to switch occurred relatively quickly and occurred early on during follow-up (129 days in switchers, 211 days for continuers), this bias may be minimal.

Reasons for treatment discontinuation and switching were not available. In a similar vein, as mentioned previously, the decision-making process at each VA facility regarding use of non-formulary IFX products was not evaluated. Understanding reasons for treatment choice and any subsequent treatment discontinuation or switching will be important for future research.

Furthermore, since the VA formulary was updated in May 2017 to include IFX-dyyb and was later updated in 2018 to remove and replace innovator IFX and IFX-dyyb with IFX-abda, these changes in practice patterns may have impacted outcomes assessed in the current study. The formulary allowed veterans with prior IFX experience to continue using the non-formulary product, but IFX-naïve patients were directed to use the formulary product. Although alternatives are still available via non-formulary requests, there is the additional layer of difficulty in adding these products, resulting in the likelihood of IFX-abda being prescribed. Relatedly, because the study time period included years prior to specificity of IFX biosimilar administrative codes, the database could not always distinguish between different IFX biosimilars. As a result, this study did not assess switching between IFX biosimilars (i.e. IFX-abda and IFX-dyyb), and thus it is difficult to assess the impact of formulary changes on the patterns observed. However, this study aimed to evaluate treatment patterns after switching to an IFX biosimilar and was not designed to assess the impact of formulary changes.

Finally, as the patients included in this study were military veterans, the results related to treatment patterns may not be generalizable to the general population. For instance, male patients will be overrepresented. In the same vein, because this study was conducted within the VA system, VA-specific treatment patterns were captured, which may not extend to the general US practice setting. Lastly, any care received outside of the VA health care program was not captured.

Conclusion

This retrospective study found that both incident and prevalent patients switching from innovator to biosimilar IFX were more likely to discontinue treatment and switch to another innovator biologic, notably back to innovator IFX, than those remaining on innovator IFX. Because the reasons for switching and discontinuation are unknown, additional research is needed to understand the higher rates of switching and discontinuation among patients who switched to an IFX biosimilar and its potential impact on clinical outcomes.

Additionally, understanding the barriers, processes, and variations in the development and implementation of a formulary may provide further insights into the frequent switching between IFX innovators and biosimilars that were found in this study. Real-world research will be crucial in a world where there are multiple biosimilars for each innovator biologic, and formulary changes leading to multiple switching between versions of a molecule are likely to occur with unknown consequences on clinical and economic outcomes.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Financial support for this research was provided by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. The study sponsor was involved in several aspects of the research, including the study design, the interpretation of data, the writing of the manuscript, and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

IL and RM are employees of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC and stockholders of Johnson & Johnson. PL, MD, BE, AL, and CN are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has provided paid consulting services to Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, which funded the development and conduct of this study and manuscript. YYX’s institution received research funding for participating in this study. RHB and MW were employees of Analysis Group, Inc. at the time the study was conducted. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

Data collection and analyses were carried out by RHB, PL, MD, BE, AL, CN, and MW. All authors participated in the conception and design of the study, the interpretation of data, manuscript preparation, and manuscript review and editing, and all approve the final manuscript for publication.

Acknowledgements

Administrative and analytical support were provided by the Clinical Epidemiology Program at White River Junction VA Medical Center, Vermont. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Veterans Health Administration or the United States Government.

References

- Vangeli E, Bakhshi S, Baker A, et al. A systematic review of factors associated with non-adherence to treatment for immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Adv Ther. 2015;32(11):983–1028.

- Hunter TM, Boytsov NN, Zhang X, et al. Prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in the United States adult population in healthcare claims databases, 2004-2014. Rheumatol Int. 2017;37(9):1551–1557.

- Shivashankar R, Tremaine WJ, Harmsen WS, et al. Incidence and prevalence of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis in Olmsted County, Minnesota from 1970 through 2010. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(6):857–863.

- Kuek A, Hazleman BL, Ostor AJ. Immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMIDs) and biologic therapy: a medical revolution. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83(978):251–260.

- Hanauer SB. The expanding role of biologic therapy for IBD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7(2):63–64.

- Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies. REMICADE (infliximab) Highlights of Prescribing Information. 2018. p. 1–21.

- Melsheimer R, Geldhof A, Apaolaza I, et al. Remicade® (infliximab): 20 years of contributions to science and medicine. Biologics. 2019;13:139–178.

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Biosimilar and Interchangeable Products 2017. [cited 2019 December 17]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/biosimilars/biosimilar-and-interchangeable-products.

- Olech E. Biosimilars: rationale and current regulatory landscape. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;45(5 Suppl):S1–S10.

- Jacobs I, Petersel D, Isakov L, et al. Biosimilars for the treatment of chronic inflammatory diseases: a systematic review of published evidence. BioDrugs. 2016;30(6):525–570.

- CELLTRION, Inc. INFLECTRA® (infliximab-dyyb) Highlights of Prescribing Information. 2019. p. 1–43.

- CELLTRION I. INFLECTRA® (infliximab-dyyb) Highlights of Prescribing Information 2019.

- Inc A. AVSOLA (infliximab-axxq) Highlights of Prescribing Information 2019.

- Co SB. RENFLEXIS (infliximab-abda) Highlights of Prescribing Information. 2019.

- Pharmaceuticals PI. IXIFI (infliximab-qbtx) Highlights of Prescribing Information. 2020.

- Teeple A, Ellis LA, Huff L, et al. Physician attitudes about non-medical switching to biosimilars: results from an online physician survey in the United States. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35(4):611–617.

- Jorgensen KK, Olsen IC, Goll GL, et al. Switching from originator infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 compared with maintained treatment with originator infliximab (nor-SWITCH): a 52-week, randomised, double-blind, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10086):2304–2316.

- Smolen JS, Choe JY, Prodanovic N, et al. Safety, immunogenicity and efficacy after switching from reference infliximab to biosimilar SB2 compared with continuing reference infliximab and SB2 in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results of a randomised, double-blind, phase III transition study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(2):234–240.

- Avouac J, Molto A, Abitbol V, et al. Systematic switch from innovator infliximab to biosimilar infliximab in inflammatory chronic diseases in daily clinical practice: the experience of cochin university hospital, paris, France. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2018;47(5):741–748.

- Gentileschi S, Barreca C, Bellisai F, et al. Switch from infliximab to infliximab biosimilar: efficacy and safety in a cohort of patients with different rheumatic diseases response to: Nikiphorou E, kautiainen H, hannonen P, et al. Clinical effectiveness of CT-P13 (infliximab biosimilar) used as a switch from remicade (infliximab) in patients with established rheumatic disease. Report of clinical experience based on prospective observational data. Expert opin biol ther. 2015;15:1677-1683. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2016;16(10):1311–1312.

- Glintborg B, Sorensen IJ, Loft AG, et al. A nationwide non-medical switch from originator infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 in 802 patients with inflammatory arthritis: 1-year clinical outcomes from the DANBIO registry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(8):1426–1431.

- Tweehuysen L, van den Bemt BJF, van Ingen IL, et al. Subjective complaints as the main reason for biosimilar discontinuation after open-label transition from reference infliximab to biosimilar infliximab. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(1):60–68.

- Scherlinger M, Germain V, Labadie C, et al. Switching from originator infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 in real-life: the weight of patient acceptance. Joint Bone Spine. 2018;85(5):561–567.

- Reuber K, Kostev K. Prevalence of switching from two anti-TNF biosimilars back to biologic reference products in Germany. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019;57(6):323–328.

- Rezk MF, Pieper B. Treatment outcomes with biosimilars: be aware of the nocebo effect. Rheumatol Ther. 2017;4(2):209–218.

- Fleischmann R, Jairath V, Mysler E, et al. Nonmedical switching from originators to biosimilars: does the nocebo effect explain treatment failures and adverse events in rheumatology and gastroenterology? Rheumatol Ther. 2020;7(1):35–64.

- Fitzgerald T, Melsheimer R, Lafeuille MH, et al. Switching and discontinuation patterns among patients stable on originator infliximab who switched to an infliximab biosimilar or remained on originator infliximab. Biologics. 2021;15:1–15.

- Johnson JAJ, Curtis JR, Pinnell DK, et al. P1570: Infliximab Biosimilar use for Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A National Veterans Affairs Experience. ACG 2020. Annual Scientific Meeting; Virtual2020.

- Lund JL, Horvath-Puho E, Komjathine Szepligeti S, et al. Conditioning on future exposure to define study cohorts can induce bias: the case of low-dose acetylsalicylic acid and risk of major bleeding. Clin Epidemiol. 2017;9:611–626.

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383.

- Yazici Y, Xie L, Ogbomo A, et al. Analysis of real-world treatment patterns in a matched rheumatology population that continued innovator infliximab therapy or switched to biosimilar infliximab. Biologics. 2018;12:127–134.

- Phillips K, Juday T, Zhang Q, et al. SAT0172 economic outcomes, treatment patterns, and adverse events and reactions for patients prescribed infliximab or ct-p13 in the Turkish population. Annals Rheumatic Dis. 2017;76(Suppl 2):835.1–835.

- Bakalos G, Zintzaras E. Drug discontinuation in studies including a switch from an originator to a biosimilar monoclonal antibody: a systematic literature review. Clin Ther. 2019;41(1):155–173 e13.

- Ho SL, Niu F, Pola S, et al. Effectiveness of switching from reference product infliximab to Infliximab-Dyyb in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in an integrated healthcare system in the United States: a retrospective, propensity score-matched, non-inferiority cohort study. BioDrugs. 2020;34(3):395–404.

- Fleischmann RM, Blanco R, Hall S, et al. Switching between Janus kinase inhibitor Upadacitinib and adalimumab following insufficient response: efficacy and safety in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80(4):432–439.

- Madenidou A, Jeffries A, Varughese S, et al. Switching patients with inflammatory arthritis from etanercept (Enbrel®) to the biosimilar drug, SB4 (Benepali®): a single-centre retrospective observational study in the UK and a review of the literature. MJR. 2019;30(Suppl 1):69–75.

- Alten R, Neregard P, Jones H, et al. SAT0161 preliminary real world data on switching patterns between etanercept, its recently marketed biosimilar counterpart and its competitor adalimumab, using Swedish prescription registry. Annals Rheumatic Dis. 2017;76(Suppl 2):831.

- Teeple A, Ginsburg S, Howard L, et al. Patient attitudes about non-medical switching to biosimilars: results from an online patient survey in the United States. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35(4):603–609.

- Boone NW, Liu L, Romberg-Camps MJ, et al. The nocebo effect challenges the non-medical infliximab switch in practice. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;74(5):655–661.

- Mahmmod S, Schultheiss JPD, van Bodegraven AA, et al. Outcome of reverse switching from CT-P13 to originator infliximab in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;27(12):1954–1962.

- Afzali A, Furtner D, Melsheimer R, et al. The automatic substitution of biosimilars: definitions of interchangeability are not interchangeable. Adv Ther. 2021;38(5):2077–2093.

- Baker JF, Leonard CE, Lo Re V, 3rd, et al. Biosimilar uptake in academic and veterans health administration settings: Influence of institutional incentives. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72(7):1067–1071.

- Burk M, Furmaga E, Dong D, et al. Multicenter drug use evaluation of tamsulosin and availability of guidance criteria for nonformulary use in the veterans affairs health system. J Manag Care Pharm. 2004;10(5):423–432.

- Gellad WCB, Lowe JC, Donohue JM. Variation in prescription use and spending for lipid-lowering and diabetes medications in the VA healthcare system. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(10):741–750.

- Radomski TR, Good CB, Thorpe CT, et al. Variation in formulary management practices within the department of veterans affairs health care system. JMCP. 2016;22(2):114–120.

- Feagan BG, Marabani M, Wu JJ, et al. The challenges of switching therapies in an evolving multiple biosimilars landscape: a narrative review of current evidence. Adv Ther. 2020;37(11):4491–4518.

- Mahmmod S, Schultheiss J, Tan A, et al. Reasons for and effectiveness of switching back to originator infliximab after a prior switch to CT-P13 biosimilar. J Crohn's Colitis. 2020;14(Supplement_1):S316–S317.

- Pernes TPM, Khan N, Crescenz MJ, P1597 (S0792). The Safety of Switching From Originator Infliximab or Biosimilar CT-P. 13 to SB2 Among a Nationwide Cohort of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients. ACG 2020 Annual Scientific Meeting; Virtual; 2020.

- Moorkens E, Godman B, Huys I, et al. The expiry of Humira® market exclusivity and the entry of adalimumab biosimilars in Europe: an overview of pricing and national policy measures. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:591134.

- Jensen TB, Kim SC, Jimenez-Solem E, et al. Shift from adalimumab originator to biosimilars in Denmark. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(6):902–903.

- Dutta B, Huys I, Vulto AG, et al. Identifying key benefits in European off-patent biologics and biosimilar markets: it is not only about price!. BioDrugs. 2020;34(2):159–170.

- Kim Y, Kwon HY, Godman B, et al. Uptake of biosimilar infliximab in the UK, France, Japan, and Korea: budget savings or market expansion across countries? Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:970.

- Brown CN, McCann E. Cost of switching from an originator biologic (Remicade) to a biosimilar. Value in Health. 2016;19(7):A581.

- Bhat S, Qazi T. Switching from infliximab to biosimilar in inflammatory bowel disease: a review of existing literature and best practices. Crohn's Colitis 360. 2021;3(1):1–6.

- Liu Y, Yang M, Garg V, et al. Economic impact of non-medical switching from originator biologics to biosimilars: a systematic literature review. Adv Ther. 2019;36(8):1851–1877.

- Gibofsky A, Skup M, Yang M, et al. Short-term costs associated with non-medical switching in autoimmune conditions. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2019;37(1):97–105.

- San-Juan-Rodriguez A, Gellad WF, Good CB, et al. Trends in list prices, net prices, and discounts for originator biologics facing biosimilar competition. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(12):e1917379.

- Hernandez I, Good CB, Shrank WH, et al. Trends in Medicaid Prices, Market Share, and Spending on Long-Acting Insulins, 2006–2018. JAMA. 2019;321(16):1627–1629.

- Yazdany J, Dudley RA, Lin GA, et al. Out-of-Pocket Costs for Infliximab and its biosimilar for rheumatoid arthritis under Medicare part D. JAMA. 2018;320(9):931–933.

- El-Gabalawy H, Guenther LC, Bernstein CN. Epidemiology of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: incidence, prevalence, natural history, and comorbidities. J Rheumatol Suppl. 2010;85:2–10.

- Howe CJ, Cole SR, Lau B, et al. Selection bias due to loss to follow up in Cohort studies. Epidemiology. 2016;27(1):91–97.