Abstract

Background

Paracetamol is the commonest analgesic worldwide in primary care. Despite evidence-based recommendations for management of acute and chronic pain with paracetamol, practices seem to vary considerably in its modalities of use, with or without restrictions, between renowned scientific societies and over time.

Objective

Qualitative assessment of similarities, differences, and changes over time in guidelines for paracetamol use in acute and chronic pain.

Methods

We focused on two common pain conditions for which paracetamol is widely used: acute migraine and chronic knee osteoarthritis (OA). In 19 guidelines (10 for acute migraine, 9 for chronic knee OA) from 10 scientific societies (AAN/AHS, ACR/AF, CHS, EFNS, EHF/LTB, ESCEO, EULAR, SFEMC, SRF, OARSI) published between 1997 and 2021, methods, results and conclusions were compared, between guidelines and over time.

Results

In acute migraine, there was a shift from no recommendation for paracetamol or recommendation only for mild attacks to recommendation for mild to moderate attacks in updated guidelines, without restriction for use for four of the five scientific societies. In knee OA, although updated guidelines generally used the GRADE system, recommendations remained heterogeneous between scientific societies: recommendation without or with restrictions, or not recommended. Consensus is lacking regarding long-course safety and efficacy in acute pain and pain at mobilization.

Conclusions

Most migraine guidelines now recommend paracetamol for mild to moderate pain. Knee OA guidelines vary on the use of paracetamol: a more holistic approach is needed for this condition, considering patient profile, disease stage, and pain management during physical activity to clarify its appropriate use.

Introduction

First introduced in 1893Citation1, paracetamol (acetaminophen, APAP, or N-acetyl para-aminophenol) is one of the most common drugs taken to relieve pain. It is available over the counter (OTC) for routine pain self-management in numerous countriesCitation2. In Europe, the highest paracetamol-consuming countries are France, Denmark, UK, and Spain, with >50 daily doses per 1000 inhabitantsCitation3.

Several evidence-based good practice guidelines regarding the place of paracetamol in the treatment of acute or chronic pain have appeared over the past 15 years. Concerns about the quality, reliability, and independence of earlier guidelinesCitation4 led to standardizing guidelines quality by developing the Appraisal of Guidelines, Research and Evaluation (AGREE) instrument in 2003, updated in 2009 (AGREE II describing the strategy used to search for and select evidence)Citation5–6, and the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE, standardizing the question of interest and the assessment of the quality of evidence)Citation7.

The objective of this study was to analyze the similarities, differences, and evolution over time in paracetamol guidelines in acute and chronic pain, focusing on acute migraine as an example of recurrent acute pain, and knee OA as an example of chronic pain. Migraine is the most disabling primary headache disorder and a common leading cause of years lived with disability worldwide, ranking first among young womenCitation8–9. Knee OA concerned 654 million individuals (40 years and older) worldwide in 2020, and around 87 million individuals (20 years and older) had incident knee OACitation10. With an ageing population and increasing prevalence of obesity, the burden of OA will continue to increase, putting more pressure on health care systemsCitation11.

Our approach was original as it was based on a concomitant analysis of guidelines (comparison between guidelines and over time), which aims at a better understanding of recommendations and may contribute to improve therapeutic choice.

Material and methods

Five experts (pain specialists and clinical pharmacologists) conducted a qualitative analysis of guidelines for paracetamol. Inclusion criteria comprised: (1) official guidelines proposed by reference organizations in two chosen fields: acute migraine or knee OA; (2) well-established guidelines from France, Europe, USA/Canada, or international guidelines; and (3) latest updated published guidelines (N) and their preceding version (N − 1). A total of 19 guidelines were identified and included: 10 concerned acute migraine (five between 1997 and 2014 (N − 1); five between 2009 and 2021 (N)), and nine concerned chronic knee OA (four between 2003 and 2016 (N − 1); five between 2018 and 2020 (N)).

For acute migraine, guidelines were published by the American Headache Society (AHSCitation12) formerly American Academy of Neurology (AANCitation13); French headache society also known as Société Française d’Etudes des Migraines et Céphalées (SFEMCCitation14–15); Canadian Headache Society (CHSCitation16–17); European Federation of Neurological Societies (EFNSCitation18–19); and European Headache Federation/Lifting The Burden (EHF/LTBCitation20–21) ( and Supplementary Table 1a).

Table 1. Acute migraine: selected guidelines.

For knee OA, guidelines were published by the American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation (ACRCitation22, ACR/AFCitation23); European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases (ESCEOCitation24–25); European League Against Rheumatism (EULARCitation26–27); Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSICitation28–29); and Société Française de Rhumatologie (SFRCitation30) ( and Supplementary Table 2a).

Table 2. Knee OA: selected guidelines.

For each guideline, the following parameters were assessed: criteria used to define acute migraine or knee OA; number and quality of studies selected; inclusion of meta-analyses; quality of reporting (GRADE, AGREE, other); strength of recommendation; the place of paracetamol in the therapeutic algorithm; and recommendations regarding dosages and precautions of use.

Results

Acute migraine

Comparison of recent guidelines (2009–2021)

In recent guidelines, the level of recommendation was based on the severity of acute migraine (mild, moderate, severe) for the CHS, EFNS, and SFEMC; or on the level of disability induced by migraine attacks for the AHS (non-incapacitating attacks defined by <20% vomiting attacks and no need for bed rest). The number and quality of selected studies are indicated in Supplementary Table 1b. The AHS, EFNS, and SFEMC recommendations were based only on clinical studies, whereas the CHS recommendation included one Cochrane meta-analysis. One RCT was considered by four of the five guidelines. Regarding methods of reporting, the CHS applied GRADE, and the SFEMC applied AGREE (Supplementary Table 1c), while other scientific societies did not mention the use of these methods.

Current recommendations for paracetamol and their strength (or level of evidence) were consistent between guidelines (Supplementary Table 1d and panel B). Thus paracetamol (1000 mg, oral) was strongly recommended by the AHS (“level A”) for non-incapacitating attacks; and by the CHS (“strong recommendation, high quality evidence”), the EFNS (“level of recommendation: A”), and the SFEMC (“high” recommendation, “high” level of evidence) for mild to moderate attacks. In contrast, the EHF/LTB guidelines recommended paracetamol (1000 mg, oral) only when NSAIDs were contraindicated (without further specification). Thus, paracetamol is currently recommended in acute migraine, without conditions by four of the five scientific societies.

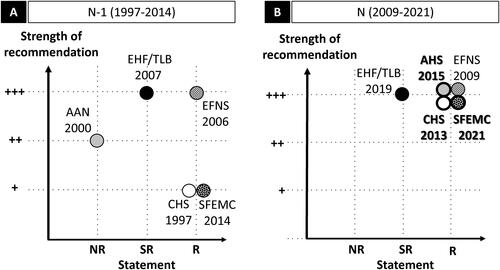

Figure 1. Acute migraine: graphic representation of paracetamol recommendations according to the statement and the strength of the recommendation. Abbreviations. AAN, American Academy of Neurology; AHS, American Headache Society; CHS, Canadian Headache Society; EFNS, European Federation of Neurological Societies; EHF, European Headache Federation; LTB, Lifting The Burden; N, current recommendation; N − 1, previous recommendation; NR, non-recommended; R, recommended; SFEMC, Société Française d’Etudes des Migraines et Céphalées; SR, specific recommendation. Panel A and panel B graphically present the position of the N − 1 and N recommendations respectively, with statement in the x-axis, and the strength of the recommendations in the y-axis. For the x-axis, recommendations are classified in three levels: NR, SR, and R. SR means that the paracetamol may be used under certain specific conditions. The specific conditions are as follows: for the EHF/LTB (both 2007 and 2009), paracetamol is recommended if NSAIDs are contraindicated. For the y-axis, the three levels range from weak (+) to strong (+++). The EHF/LTB did not mention a strength for their recommendation (and level of evidence), in this case the recommendation is considered +++ by default. The AHS 2015 did not mention a strength for their recommendation but had a level of evidence (level A for “non-incapacitating attacks: paracetamol 1000 mg”), in this case the recommendation was considered +++ by default. For more details, see Supplementary Table 1d.

Evolution of guidelines over time

The comparison between earlier (1997–2014; panel A) and current (2009–2021; panel B) guidelines showed a shift in the level of recommendations for paracetamol from three of five scientific societies. The CHS recommended paracetamol only for mild attacks in 1997 (level III), and now also recommends it for moderate attacks. This change was based on a Cochrane systematic review (2010) which concluded that paracetamol 1,000 mg alone may be a useful first-line treatment for individuals with migraine that does not cause severe disability. The AAN/AHS did not recommend paracetamol in 2000 (grade B), but now (since 2015) recommends it for non-incapacitating attacks based on a high quality RCT (double-blind, placebo-controlled efficacy and safety trial) published in 2000. In 2014, French recommendations from the SFEMC recommended paracetamol only as a non-specific treatment with low level of evidence (grade C); based on two newer RCTs, the revised SFEMC recommendations issued in 2021 reassessed the status of paracetamol and stated that the drug was “effective in reducing migraine pain, but only in attacks of mild-to-moderate intensity with few bothersome symptoms” (Supplementary Table 1b).

Chronic knee OA

Comparison of recent guidelines (2018–2020)

In recent guidelines, the ESCEO stratified knee OA stepwise according to severity. The OARSI defined subgroups according to comorbidities. Regarding selection criteria, the OARSI considered only RCTs, while the ESCEO included non-RCTs; and the ACR/AF, ESCEO and SFR considered systematic reviews (SRs) and/or meta-analyses (Supplementary Table 2 b). GRADE was applied by the OARSI, ACR/AF, and ESCEO (Supplementary Table 2c).

Current recommendations for paracetamol and their strength (or level of evidence) varied between guidelines (Supplementary Table 2d and panel B), as did the type of studies considered (Supplementary Table 2b). The EULAR recommended paracetamol in first line without restrictions, with topical agents. For the SFR, oral paracetamol should not be prescribed systematically and/or continuously (category 1 A, level A). The ESCEO recommended it as step 1 (before oral NSAIDs) with restrictions (short-term and rescue medicine) in addition to first-line treatment with SYSADOA (weak recommendation). The ACR/AF recommended paracetamol (conditional strength) as an alternative to NSAIDs with restrictions (short term and episodic use), while the OARSI “conditionally not recommend” it (level 4 A and 4B). Thus, paracetamol is currently recommended in knee OA without any restriction for use by one scientific society, recommended with restrictions for use by three, and not recommended by one.

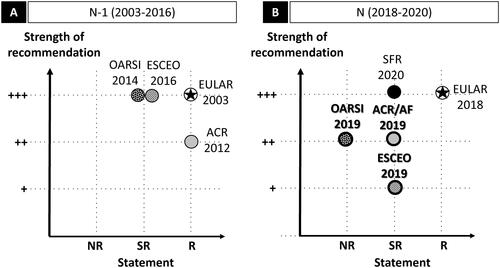

Figure 2. Knee OA: graphic representation of paracetamol recommendations according to the statement and the strength of the recommendation. Abbreviations. ACR/AF, American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation; ESCEO, European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases; EULAR, European League Against Rheumatism; N, current recommendation; N − 1, previous recommendation; NR, non-recommended; OARSI, Osteoarthritis Research Society International; R, recommended; SFR, Société Française de Rhumatologie; SR, specific recommendation. Panel A and panel B graphically present the position of the N − 1 and N recommendations, respectively, with the statement in the x-axis, and the strength of the recommendation in the y-axis. For the x-axis, recommendations are classified in three levels: NR, SR, and R. SR means that the paracetamol may be used under certain specific conditions. The specific conditions are as follows: for the OARSI 2014, paracetamol is appropriate for OA patients without comorbidity, at conservative dose and treatment duration consistent with approved prescribing limits; for the ESCEO (both 2016 and 2019), paracetamol is recommended as short-term rescue analgesia in step 1; for the ACR/AF 2019, paracetamol is recommended for short-term and episodic use for intolerance or contraindication to NSAIDs; for the SFR 2020, paracetamol is not recommended for systematic and/or continuous prescription. Star (★) indicates that paracetamol is prescribed as first-line treatment. For the y-axis, the three levels range from weak (+) to strong (+++). For the ESCEO 2016 (N − 1) which did not mention a strength (and level of evidence), the recommendation is considered +++ by default. No previous guideline (N − 1) for knee OA exists for the SFR; for the EULAR, no re-evaluation has been performed since 2003 (N − 1). The ESCEO developed a stepwise algorithm and stratified knee OA according to pharmacological treatment and severity (Step 1: background treatment; Step 2: advanced pharmacological treatment, Step 3: last pharmacological attempts, Step 4: end-stage disease management and surgery). The OARSI defined patient subgroups (“no comorbidities”, “gastrointestinal comorbidities”, “cardiovascular comorbidities”, “frailty”, and “widespread and pain/or depression”). For more details, see Supplementary Table 2d.

Evolution of guidelines over time

Comparison between earlier (2003–2016; panel A) and current (2018–2020; panel B) guidelines was possible for three scientific societies. The ACR/AF did not change their strength of recommendation and now specifies: “For those with limited pharmacologic options due to intolerance of or contraindications to the use of NSAIDs, acetaminophen may be appropriate”. The ESCEO slightly modified its recommendation: it initially advocated paracetamol as short-term rescue medication without specifying the strength of recommendation, but now states that this is a weak recommendation. In its previous recommendation, the OARSI recommended paracetamol as “appropriate” treatment (maximum level) for individuals without relevant comorbidities, whereas now paracetamol is no longer recommended, regardless of clinical phenotype, for chronic knee OA pain. In its previous guideline, the OARSI did not mention applying GRADE, and evaluation of paracetamol efficacy was based on one conference Abstract (poster presentation), whereas the current guideline applies GRADE and mentions several RCTs in its references (Supplementary Table 2b and Supplementary Table 2c).

Discussion

We conducted a qualitative expert review of similarities, differences, and changes over time between guidelines, from 10 renowned national and international scientific societies regarding the use of paracetamol, the most widely used analgesic worldwide, in acute migraine and chronic knee OA.

In acute migraine, we observed a trend toward non-specific recommendation of paracetamol by most scientific societies for mild to moderate attacks, while previous guidelines did not recommend it or recommended it for restricted indications. Thus, while in 1997 the CHS recommended paracetamol for mild migraine attacks with a low level of evidenceCitation16, it is now recommended for both mild and moderate attacksCitation17. Similarly, in 2000 the AAN did not recommend paracetamol for acute migraineCitation13, while they now recommend it for non-incapacitating attacksCitation12. A similar trend was observed for the updated French guidelinesCitation14–15. The main reason may be the fact that the severity of acute migraine and its functional impact are now increasingly acknowledged and considered in recent guidelines. Previous French guidelines only considered patients with severe attacks in whom paracetamol is not effective, whereas recommendations should have a broader scope. In 2021, paracetamol was repositioned for mild to moderate attacks which represent almost 80% of attacks. Another reason is the increasing consideration of the potential gastrointestinal risks of NSAIDsCitation31, also particularly of contraindications for patients with cardiovascular and renal impairmentCitation32–35. For these reasons paracetamol is recommended in first line for mild to moderate migraine attacks. Other guidelines than those considered here also recommend the use of paracetamol in the treatment of acute migraine: e.g. the UK guidelines recommend paracetamol as monotherapy depending on the patient’s preference, comorbidities, and risk of adverse eventsCitation36.

In chronic painful knee OA, four of five updated guidelines (EULAR, ACR/AF, ESCEO and SFR) recommend paracetamol, but three (ACR/AF, ESCEO and SFR) only for non-chronic use (“short-term use”, “episodic use”, “not systematically and/or continuously”). The fifth guideline (OARSI) specifies that paracetamol should be “conditionally not recommended”. Interestingly almost all guidelines used similar methods of assessment, and in particular the GRADE system, which was developed to standardize the quality of the question of interest and the assessment of the quality of evidenceCitation7. These discrepancies may relate to distinct selection criteria (the OARSI guideline considered only RCTs, the ESCEO guideline considered non-RCT studies, and the ACR/AF, ESCEO and SFR considered meta-analyses). Due to the cost of RCTs, very few studies have been carried out on paracetamol for knee OA over the past years; hence guidelines from scientific societies were also based on other types of studies, such as prospective observational studies. However, more general reasons probably account even more for these discrepancies. Thus, the ESCEO guideline considered the stage of OA and the OARSI considered comorbidities in their level of recommendation. Another reason might be the increasing awareness of potential safety issues with paracetamol, guided by universal principles of precaution. Thus, recent publications raised the potential risk of adverse effects when taking paracetamol for a long period of timeCitation37–39. These publications had an impact on the experts’ judgment and may have been the main reason for its recommendation as short-term medication in most updated guidelines. Of note, a recent Cochrane meta-analysis performed to assess the benefits and harms of paracetamol compared with placebo in the treatment of OA of the hip or knee, showed no difference in adverse events overall, and modest therapeutic efficacyCitation40. However, included RCTs in this review did not consider pain relieved by one-off use of paracetamol (e.g. pain at mobilization). Paracetamol is less potent than opioids and NSAIDs, but its main advantage is its high safety and tolerability profile, which makes it particularly suitable for pregnant women and frail patients. Despite the physiological and pharmacokinetic changes associated with aging, paracetamol is also considered safe and effective in elderly patientsCitation41–42, who are particularly affected by OA. Hence despite several studies focusing on the potential risks of hepatic toxicity with long-term use of paracetamol (7% abnormal liver function according to the Cochrane meta-analysis versus 1.8% for the placebo in knee or hip OA), most experts concur that paracetamol should still be considered a first-line analgesic for acute mild to moderate pain in patients with cardiovascular or gastrointestinal disorders, kidney or liver diseases, and asthmaCitation41. These considerations have to be seen in the context of the identified gastric, renal or cardiovascular adverse effects of long-term NSAIDsCitation43–45. These guidelines tended to neglect pragmatic considerations such as real-life data regarding paracetamolCitation46–47 and expert advice. Real-life data collected from patients and their general practitioner should be considered to improve the relevance of the recommendations.

Several recent publications have reviewed guidelines on paracetamol for headache disorders or musculoskeletal painCitation48–50. Vaz et al.Citation48 conducted a systematic search and meta-analysis using AGREE II to evaluate the quality of clinical practice guidelines for the acute treatment of episodic tension-type headache and migraine. Their analysis was based on three UK headache associations (British Association for the Study of Headache, NICE, Scottish lntercollegiate Guidelines Network), CHS (Canada) and EFH (EU). Our analysis was not based on the same scientific societies, since it included the French (SFEMC) and American (AHS/AAN) scientific societies. Freo et al.Citation49 conducted a scoping review of recommendations on paracetamol for pain (headache, OA, axial spondylarthritis, low back pain, musculoskeletal pain and cancer pain), while Shaheed et al.Citation50 performed a systematic review of systematic reviews covering 44 pain conditions including knee and hip OA. Contrary to these studies, our analysis focused on knee OA as an example of chronic condition (because of heterogeneity in the anatomical locations of OA) and on acute migraine as an example of recurrent acute pain condition.

The strength of our review was that we performed a concomitant analysis of (1) the similarities and differences in guidelines provided by several renowned scientific societies, and (2) their evolution over time. This provided us with a global view of the past and current recommendations for paracetamol and its changes over time. However, this work presented limitations, as it was not intended to be a systematic and quantitative review of guidelines.

We here conducted a qualitative assessment of well-established guidelines from France, Europe, USA/Canada, or international guidelines, and well-known to practitioners. We cannot directly conclude whether the results of our analysis may be applied to other pain conditions as regards paracetamol efficacy. However, we think that the safety and tolerability profile of paracetamol, the adherence to the rules of good use, and its use in young patients with acute migraine or elderly or frail patients with chronic conditions, may be generalized to other pain populations.

Conclusions

This qualitative analysis emphasizes evolutions in practice guidelines over time in different scientific societies regarding the place of paracetamol in acute migraine and chronic knee OA. In acute migraine, there was a positive evolution in paracetamol recommendations in the latest guidelines, and most guidelines now recommend it for mild to moderate pain. In chronic knee OA, there were important discrepancies regarding the place of paracetamol, which highlights the need for a more holistic approach for this condition considering patient profile, disease stage, and pain management at mobilization to clarify appropriate use.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Medical writing and article processing charges for this article are supported by UPSA.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

Within the last 36 months, the authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: AE receives or has received consulting fees from APTYS PHARMA, UNITHER and UPSA. JD receives or has received consulting fees from UPSA. MLM receives or has received grants or contracts from ELI LILLY, LUNDBECK, NOVARTIS, TEVA; and consulting fees from ABBVIE, ELI LILLY, GRÜNENTHAL, LUNDBECK, NOVARTIS, SUN, UPSA, ZAMBON. NA receives or has received consulting fees from GRÜNENTHAL, MERZ PHARMA, NOVARTIS, PFIZER, SANOFI, UPSA; and payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from GRÜNENTHAL. SP receives or has received grants or contracts from GRÜNENTHAL, PFIZER, SANOFI; consulting fees from ABBVIE, GRÜNENTHAL, MENARINI, PFIZER, SANOFI, SOBI, UPSA, ZAMBON; and payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from GRÜNENTHAL, MENARINI, PFIZER, SANOFI. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

All authors were involved in the conception and design of the study, the analysis and interpretation of the data; the critical review of the intellectual content of the article, and the final approval of the version to be published; all authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Supplementary_Table_2d.pdf

Download PDF (94.3 KB)Supplementary_Table_2c.pdf

Download PDF (103.2 KB)Supplementary_Table_2b.pdf

Download PDF (140.8 KB)Supplementary_Table_2a.pdf

Download PDF (104 KB)Supplementary_Table_1d.pdf

Download PDF (96.4 KB)Supplementary_Table_1c.pdf

Download PDF (106.4 KB)Supplementary_Table_1b.pdf

Download PDF (103.4 KB)Supplementary_Table_1a.pdf

Download PDF (100.7 KB)Acknowledgements

All authors want to thank Rassa Pegahi (UPSA) for coordinating the project; Iain McGill and Jennifer Bonini (Abelia Science) for the medical writing.

References

- Przybyła GW, Szychowski KA, Gmiński J. Paracetamol - an old drug with new mechanisms of action. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2021;48(1):3–19.

- Gaul C, Eschalier A. Dose can help to achieve effective pain relief for acute mild to moderate pain with over-the-counter paracetamol. TOPAINJ. 2018;11(1):12–20.

- Hider-Mlynarz K, Cavalié P, Maison P. Trends in analgesic consumption in France over the last 10 years and comparison of patterns across Europe. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;84(6):1324–1334.

- Grilli R, Magrini N, Penna A, et al. Practice guidelines developed by specialty societies: the need for a critical appraisal. Lancet. 2000;355(9198):103–106.

- Brouwers MC, Kerkvliet K, Spithoff K. The AGREE reporting checklist: a tool to improve reporting of clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016;352:i1152.

- EQUATOR: Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research. The AGREE Reporting Checklist: a tool to improve reporting of clinical practice guideline [Internet]. [Updated 2022 Nov 25; cited 2022 March 11]. Available from: https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/the-agree-reporting-checklist-a-tool-to-improve-reporting-of-clinical-practice-guidelines/.

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924–926.

- Robbins MS. Diagnosis and management of headache: a review. JAMA. 2021;325(18):1874–1885.

- Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Jensen R, et al. Migraine remains second among the world’s causes of disability, and first among young women: findings from GBD2019. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):137.

- Cui A, Li H, Wang D, et al. Regional prevalence, incidence and risk factors of knee osteoarthritis in population-based studies. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;29–30:100587.

- Arden NK, Perry TA, Bannuru RR, et al. Non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis: comparison of ESCEO and OARSI 2019 guidelines. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2021;17(1):59–66.

- Marmura MJ, Silberstein SD, Schwedt TJ. The acute treatment of migraine in adults: the american headache society evidence assessment of migraine pharmacotherapies. Headache. 2015;55(1):3–20.

- Silberstein SD. Practice parameter: evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2000;55(6):754–762.

- Lanteri-Minet M, Valade D, Geraud G, et al. Revised French guidelines for the diagnosis and management of migraine in adults and children. J Headache Pain. 2014;15(1):2.

- Ducros A, de Gaalon S, Roos C, et al. Revised guidelines of the French headache society for the diagnosis and management of migraine in adults. Part 2: pharmacological treatment. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2021;177(7):734–752.

- Pryse-Phillips WE, Dodick DW, Edmeads JG, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of migraine in clinical practice. Canadian Headache Society. CMAJ. 1997;156(9):1273–1287.

- Worthington I, Pringsheim T, Gawel MJ, et al. Canadian Headache Society Guideline: acute drug therapy for migraine headache. Can J Neurol Sci. 2013;40(5 Suppl 3):S1–S80.

- Evers S, Afra J, Goadsby PJ, et al. EFNS guideline on the drug treatment of migraine - report of an EFNS task force. Eur J Neurol. 2006;13(6):560–572.

- Evers S, Afra J, Frese A, et al. EFNS guideline on the drug treatment of migraine-revised report of an EFNS task force. Eur J Neurol. 2009;16(9):968–981.

- Steiner TJ, Martelletti P. Aids for management of common headache disorders in primary care. J Headache Pain. 2007;8(Suppl 1):S2.

- Steiner TJ, Jensen R, Katsarava Z, et al. Aids to management of headache disorders in primary care (2nd edition): on behalf of the European Headache Federation and Lifting The Burden: the Global Campaign against Headache. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1):57.

- Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64(4):465–474.

- Kolasinski SL, Neogi T, Hochberg MC, et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation guideline for the management of osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020;72(2):149–162.

- Bruyère O, Cooper C, Pelletier JP, et al. A consensus statement on the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO) algorithm for the management of knee osteoarthritis-From evidence-based medicine to the real-life setting. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;45(4 Suppl):S3–S11.

- Bruyère O, Honvo G, Veronese N, et al. An updated algorithm recommendation for the management of knee osteoarthritis from the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases (ESCEO). Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019;49(3):337–350.

- Jordan KM, Arden NK, Doherty M, et al. EULAR recommendations 2003: an evidence based approach to the management of knee osteoarthritis: report of a Task Force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(12):1145–1155.

- Geenen R, Overman CL, Christensen R, et al. EULAR recommendations for the health professional’s approach to pain management in inflammatory arthritis and osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(6):797–807.

- McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22(3):363–388.

- Bannuru RR, Osani MC, Vaysbrot EE, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019;27(11):1578–1589.

- Sellam J, Courties A, Eymard F, et al. Recommendations of the French Society of Rheumatology on pharmacological treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2020;87(6):548–555.

- Saad J, Mathew D. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs toxicity. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. [Updated 2021 Jul 21; cited 2022 March 11]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526006/

- Trelle S, Reichenbach S, Wandel S, et al. Cardiovascular safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011;342:c7086.

- Bally M, Dendukuri N, Rich B, et al. Risk of acute myocardial infarction with NSAIDs in real world use: bayesian Meta-analysis of individual patient data. BMJ. 2017;357:j1909.

- Lucas GNC, Leitão ACC, Alencar RL, et al. Pathophysiological aspects of nephropathy caused by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Bras Nefrol. 2019;41(1):124–130.

- Baker M, Perazella MA. NSAIDs in CKD: are they safe? Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;76(4):546–557.

- NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Management of migraine (with or without aura) [Internet]. [Updated 2021 May 12; cited 2022 March 11]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553317/bin/nicecg150guid_pathway1.pdf.

- De Vries F, Setakis E, van Staa TP. Concomitant use of ibuprofen and paracetamol and the risk of major clinical safety outcomes. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;70(3):429–438.

- Roberts E, Delgado Nunes V, Buckner S, et al. Paracetamol: not as safe as we thought? A systematic literature review of observational studies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(3):552–559.

- McCrae JC, Morrison EE, MacIntyre IM, et al. Long-term adverse effects of paracetamol - a review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;84(10):2218–2230.

- Leopoldino AO, Machado GC, Ferreira PH, et al. Paracetamol versus placebo for knee and hip osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;2(2):CD013273.

- Alchin J, Dhar A, Siddiqui K, et al. Why paracetamol (acetaminophen) is a suitable first choice for treating mild to moderate acute pain in adults with liver, kidney or cardiovascular disease, gastrointestinal disorders, asthma, or who are older. Curr Med Res Opin. 2022;38(5):811--825.

- Wilson SH, Wilson PR, Bridges KH, et al. Nonopioid analgesics for the perioperative geriatric patient: a narrative review. Anesth Analg. 2022. DOI:10.1213/ANE.0000000000005944

- Vonkeman HE, van de Laar MA. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: adverse effects and their prevention. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010;39(4):294–312.

- Varga Z, Sabzwari SRA, Vargova V. Cardiovascular risk of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: an under-recognized public health issue. Cureus. 2017;9(4):e1144.

- Swathi VS, Saroha S, Prakash J, et al. Retrospective pharmacovigilance analysis of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs-induced chronic kidney disease. Indian J Pharmacol. 2021;53(3):192–197.

- Battaggia A, Lora Aprile P, Cricelli I, et al. Paracetamol: a probably still safe drug. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(9):e57.

- Forestier RJ, Erol Forestier FB. Did the subjects and the controls have the same disease? Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(7):e43.

- Vaz JM, Alves BM, Duarte DB, et al. Quality appraisal of existing guidelines for the management of headache disorders by the AGREE II’s method. Cephalalgia. 2022;42(3):239–249.

- Freo U, Ruocco C, Valerio A, et al. Paracetamol: a review of guideline recommendations. JCM. 2021;10(15):3420.

- Abdel Shaheed C, Ferreira GE, Dmitritchenko A, et al. The efficacy and safety of paracetamol for pain relief: an overview of systematic reviews. Med J Aust. 2021;214(7):324–331.