Background

The COVID-19 pandemic started in China and was easily detected in less than a month in high-income countries (HICs) like the USA, Italy, Germany, and the UK. While the official reports say that lower income countries were infected later, there is no consensus about whether this was the actual case due to the lower diagnostic and surveillance capacity in low-and-middle-income countries (LMICs). But as the pandemic progressed, HICs started protecting their populations by funding corporations working on vaccines in exchange for early access to vaccinate their citizensCitation1.

At the same time, other global efforts were trying to keep equity as the market will be swallowed by HICs. Therefore, the Independent Allocation of Vaccines Group (IAVG), which was established as a collaboration between the World Health Organization (WHO) and Gavi, set the goal of vaccinating 70% of the global population by mid-2022, partly with the help of the COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX). This target was set to minimize the burden of the disease and the socio-economic effects of COVID-19Citation2,Citation3.

However, by the 22 June 2022, only 50 countries had met the target vaccination rate, the majority of which are HICs. Meanwhile, low-income countries still lack behind in vaccination coverage, having vaccinated only 10% of their populationCitation4. While HICs were offering booster doses in late 2021, 45 countries had vaccinated less than 10% of their population, and 105 had administered only the primary vaccination series to approximately 40% of their population. Moreover, many countries struggled to cover the vaccination needs of their elderly populationCitation2,Citation5.

Factors affecting vaccine uptake in LMICs

Although it is evident that the number of COVID-19 cases is declining worldwide, new outbreaks are still being recorded around the world in various placesCitation6. Therefore, the race to vaccinate the whole world population is not near an end. Even with the COVAX contribution, which has so far shipped over a billion COVID-19 vaccines to 145 participants to cover at least 40% of a country’s population vaccine needsCitation7–9, LMICs are still struggling to combat the lack of vaccine supply. To date, only 17.1% of the African population received two doses of the vaccineCitation9. The low vaccination rate caused by vaccine inequality (manifested by high uptake in more educated and richer people) in Africa may further facilitate the development of more variants, mimicking the appearance of the Omicron variantCitation10,Citation11.

Among the factors that prevented COVAX from donating the planned 8 billion vaccine doses to low-income countries are the delay of HICs to provide financial support and claiming a large amount of the manufactured vaccinesCitation5. Furthermore, a substantial part of the vaccines donated by HICs as a form of support to COVAX had a brief half-life, meaning that by the time of administration many doses had reached the expiry dateCitation3. What’s more, COVAX supply to Africa only includes AstraZeneca, Sinopharm, BioNTech, Johnson & Johnson (J&J), and Moderna and has covered 59% of total doses received. And it was also decided that AstraZeneca, a cheap vaccine, is to be the main vaccine provided by COVAXCitation2,Citation3. Along with COVAX, Africa received its COVID-19 vaccination from Africa Vaccine Acquisition Task Team, BILATERAL, some specific HICs, and other unknown sourcesCitation12.

More than a hundred nations have approved the use of AstraZeneca as part of their pandemic preparedness plans. However, various LMICs are currently rejecting or even destroying the AstraZeneca jabs sent to them. Unlike other COVID-19 vaccines that can be stored safely for up to 12 months, the shelf life of AstraZeneca is of only 6 months. This could constitute a problem when millions of jabs are delivered just before the expiry dateCitation13. This is, for example, the problem Nigeria faced last November when the government had to use near-expiry vaccines and dump around one million other jabs. Other West African countries were facing the same problem a few months after NigeriaCitation14. Coupled with low vaccination rates, high vaccine hesitancy, and logistic challenges in African countries, vaccines with short shelf life are not appealing anymoreCitation15. And because a decrease in the demand for the vaccine (manifested by the decreased uptake) typically leads to a positive movement along the supply curve, a surplus in the number of vaccines available will occur. With time, many vaccines will expire; governments will be reluctant to purchase or request new doses, and international supporters of LMICs might think twice before sending more doses that may eventually expire. Subsequently, market equilibrium will be reached with the final decrease in supply.

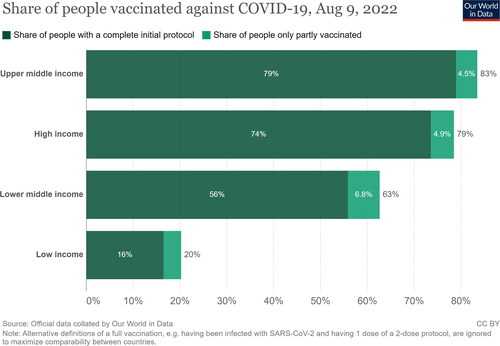

Although the WHO is encouraging rich countries to donate more vaccines with longer expiry datesCitation16, HICs continue to ship the vaccines that have a near-to-expiry date despite the possession of triple, quadruple, or quintuple the number of vaccines required by one country. And while developed countries were starting to administer booster doses, approximately three billion people worldwide were left unvaccinated, which only highlights vaccine inequity and nationalism. The WHO has long suggested delaying booster doses until the full vaccination (one dose of J&J or two doses of any other vaccine) was achieved in all countries. However, the emergence of the Omicron variant prompted developed countries’ rush to administer booster doses leaving WHO requests unansweredCitation17. By 9 August 2022, around 79% to 83% of people in high and upper-middle-income countries had achieved full vaccination coverage (defined as two doses of any vaccine or one dose of J&J), respectively; meanwhile, only 20% of low-income countries’ populations had received any vaccine ()Citation18. In addition, many HICs reported some severe and life-threatening adverse events following immunization (e.g. cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, splanchnic vein thrombosis, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, Guillain-Barré syndrome, and chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathyCitation19,Citation20) after the administration of AstraZeneca. This had made many African countries halt the distribution of the vaccine, further contributing to vaccine hesitancyCitation21. Recently, countries have rejected around 35 million AstraZeneca doses, preferring vaccines produced by J&J, Moderna, and Pfizer, insteadCitation15. Sadly, some countries, like GermanyCitation22 and other European statesCitation23, also started to refuse the one-dose J&J vaccine without a booster dose of an mRNA vaccine.

Figure 1. Share of people vaccinated against COVID-19 in countries categorized with their income status by 5 June 2022. The figure was adopted from Our World in Data at https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations, with a Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY).

Proposed solutions

Accordingly, we propose the following actions:

We believe that rich countries should consider providing poorer countries with the needed vaccines, focusing on Moderna and Pfizer when feasible.

In the case of the provision of AstraZeneca, newly manufactured vaccines should be sent to prevent their expiry before the time of administration. To properly achieve this, countries should consider estimating the actual number of needed vaccines for future booster doses and disregard storing doses that will unlikely be administered to their populations.

Additionally, all HICs should accept, recognize, and approve the administration of vaccines produced by LMICs like Sinopharm, Sinovac, and Sputnik.

Finally, AstraZeneca should consider testing the safety and efficacy of their vaccine beyond the declared “at least six months” shelf lifeCitation24. The Food and Drug Administration of Thailand (Thai FDA)Citation25 and the Indonesian governmentCitation26 approved the increase of AstraZeneca’s shelf life to nine months rather than only six based on the fact that extending shelf life will mostly not affect the safety of the vaccine, but it may lead to reduced potency, stability, and effectiveness (some protection is better than no protection)Citation25. And just like the FDA has reviewed the potential for extending the shelf life of J&J and Pfizer vaccinesCitation27,Citation28, further reviewing of the safety and effectiveness of the AstraZeneca vaccine after the six-month time point should be nudged.

Conclusion

Although the governments of HICs are to be partially blamed for some of the inequity in the COVID-19 vaccine distribution crisis in LMICs, governments of LMICs also have a duty toward the rapid distribution of the received vaccines as using near-to-expiry date vaccines can be lifesaving in many instances. But continued inequity and discrimination against LMICs will not help in lessening the frequency of viral mutationCitation29 as “no one is safe from COVID-19 until everyone is safe.”Citation30

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This paper was not funded.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

A reviewer on this manuscript has disclosed that they receive grant funding from Sanofi Pasteur and Merck Sharp and Dohme on unrelated investigator initiated grants. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

Author contributions

VPT and AMM were principally responsible for formulating the study idea and design. All authors conducted the literature search and wrote and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript under the supervision of NTH.

Acknowledgements

Authors thank the executive editor of the journal, Current Medical Research & Opinion, for the support and the helpful comments. Authors also thank the peer reviewers who were very encouraging and helped make this letter more informative, easier to follow, and more engaging.

References

- The New York Times. A timeline of the coronavirus pandemic. 2021 [cited 2022 Aug 04]. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/article/coronavirus-timeline.html

- Patel MK. Booster doses and prioritizing lives saved. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(26):2476–2477.

- World Health Organization. Achieving 70% COVID-19 immunization coverage by mid-2022. 2021 Aug 04. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/23-12-2021-achieving-70-covid-19-immunization-coverage-by-mid-2022#cms

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 vaccine demand – global event enhancing vaccine confidence and uptake among high-risk and vulnerable groups. 2022 Aug 04. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/events/detail/2022/06/22/default-calendar/covid-19-vaccine-demand–-global-event-enhancing-vaccine-confidence-and-uptake-among-high-risk-and-vulnerable-groups

- Mobarak AM, Miguel E, Abaluck J, et al. End COVID-19 in low- and Middle-income countries. Science. 2022;375(6585):1105–1110.

- Reuters. What you need to know about the coronavirus right now. 2022 [updated 2022 Apr 20; 2022 Apr 23]. Available from: https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/what-you-need-know-about-coronavirus-right-now-2022-04-20/

- World Health Organization. The Oxford/AstraZeneca (ChAdOx1-S [recombinant] vaccine) COVID-19 vaccine: what you need to know. 2022 [updated 2022 Mar 16; 2022 Apr 23]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/the-oxford-astrazeneca-covid-19-vaccine-what-you-need-to-know

- UNICEF. COVID-19 vaccine market dashboard. 2022 Apr 23. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/supply/covid-19-vaccine-market-dashboard

- Africa CDC. COVID-19 vaccination. 2022 Jun 06. Available from: https://africacdc.org/covid-19-vaccination/

- Corey L. The omicron story: The winter of our discontent [Internet]. Johns Hopkins University of Medicine. 2022. Available from: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/vaccines/blog/the-omicron-story-the-winter-of-our-discontent-3

- The Lancet Infectious Diseases. Time for Africa to future-proof, starting with COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22(2):151.

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa. Africa COVID-19 vaccination dashboard. 2022 May 27. Available from: https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiOTI0ZDlhZWEtMjUxMC00ZDhhLWFjOTYtYjZlMGYzOWI4NGIwIiwidCI6ImY2MTBjMGI3LWJkMjQtNGIzOS04MTBiLTNkYzI4MGFmYjU5MCIsImMiOjh9

- Peter Mwai in BBC. Covid-19 vaccines: why some African states can’t use their vaccines. 2021 [updated 2022 Apr 22]. Available from: https://www.bbc.com/news/56940657

- Reuters. Exclusive: Short AstraZeneca shelf life complicates COVID vaccine rollout to world’s poorest. 2022 Aug 04. Available from: https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/exclusive-short-astrazeneca-shelf-life-complicates-covid-vaccine-rollout-worlds-2022-02-16/

- Francesco Guarascio in Reuters. Poorer nations shun AstraZeneca COVID vaccine - document 2022 Apr 22. Available from https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/poorer-nations-shun-astrazeneca-covid-vaccine-document-2022-04-14/

- Euronews. Poor countries refuse 100 million COVID-19 vaccine doses set to expire. 2022 Apr 22. Available from: https://www.euronews.com/2022/01/13/poor-countries-refuse-100-million-covid-19-vaccine-doses-set-to-expire

- Adepoju P. As COVID-19 vaccines arrive in Africa, omicron is reducing supply and increasing demand. Nat Med. 2021. DOI:10.1038/d41591-021-00073-x

- Our World in Data. Coronavirus (COVID-19) vaccinations. 2022 Aug 10. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations

- European Medicines Agency. AstraZeneca’s COVID-19 vaccine: EMA finds possible link to very rare cases of unusual blood clots with low blood platelets. 2021 Aug 04. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/astrazenecas-covid-19-vaccine-ema-finds-possible-link-very-rare-cases-unusual-blood-clots-low-blood

- Oo WM, Giri P, de Souza A. AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine and Guillain-Barre syndrome in Tasmania: a causal link? J Neuroimmunol. 2021;360:577719. 15

- Pelz Deutsche Welle D. African countries temporarily suspend AstraZeneca vaccine. 2021 [cited 2022 Apr 22]. Available from: https://www.dw.com/en/african-countries-temporarily-suspend-astrazeneca-vaccine/a-56904649

- German Embassy Cairo. Important alert concerning COVID-19 vaccine certificates. 2022 Apr 23. Available from: https://www.facebook.com/german.embassy.cairo/posts/229010272755035

- Schengenvisa. Vaccine certificate validity for each Schengen/EU member state. 2022 Aug 04. Available from: https://www.schengenvisainfo.com/news/vaccine-certificate-validity-for-each-schengen-eu-member-state/

- AstraZeneca. AZD1222 vaccine met primary efficacy endpoint in preventing COVID-19. 2020 [cited 2022 Apr 26]. Available from: https://www.astrazeneca.com/media-centre/press-releases/2020/azd1222hlr.html

- World Health Organization Africa. Expiry date and shelf life of the AstraZeneca Covishield vaccine produced by the Serum Institute of India. 2021 Apr 26. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/news/expiry-date-and-shelf-life-astrazeneca-covishield-vaccine-produced-serum-institute-india

- Stanley Widianto via Reuters. EXCLUSIVE Indonesia extends AstraZeneca vaccine shelf life as 6 mln doses near expiry. 2022 Jun 06. Available from: https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/exclusive-indonesia-extends-astrazeneca-vaccine-shelf-life-6-mln-doses-near-2022-03-01/

- American Hospital Association. FDA extends shelf life for certain Pfizer vaccine vials, monoclonal antibodies. 2022 Apr 26. Available from: https://www.aha.org/news/headline/2022-04-18-fda-extends-shelf-life-certain-pfizer-vaccine-vials-monoclonal-antibodies

- American Hospital Association. FDA extends shelf life for refrigerated J&J COVID-19 vaccine. 2022 Apr 26. Available from: https://www.aha.org/news/headline/2022-03-14-fda-extends-shelf-life-refrigerated-jj-covid-19-vaccine

- Hunter DJ, Abdool Karim SS, Baden LR, et al. Addressing vaccine inequity - Covid-19 vaccines as a global public good. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(12):1176–1179.

- World Health Organization. No one is safe from COVID-19 until everyone is safe. 2021 Apr 23. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/photo-story/photo-story-detail/No-one-is-safe-from-COVID19-until-everyone-is-safe