Abstract

Objective

In this study, we examined colorectal cancer (CRC) screening adherence in Medicare beneficiaries and associated healthcare resource utilization (HCRU) and Medicare costs.

Methods

Using 20% Medicare random sample data, the study population included Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries aged 66–75 years on 1 January 2009, at average risk for CRC and continuously enrolled in Medicare Part A/B from 2008 to 2018. We excluded those who had undergone colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy during 2007–2008 and assumed everyone was due for screening in 2009; screening patterns were determined for 2009–2018. Based on US Preventive Services Task Force recommendations, individuals were categorized as adherent to screening, inadequately screened or not screened. HCRU and Medicare costs were calculated as mean per patient per year (PPPY).

Results

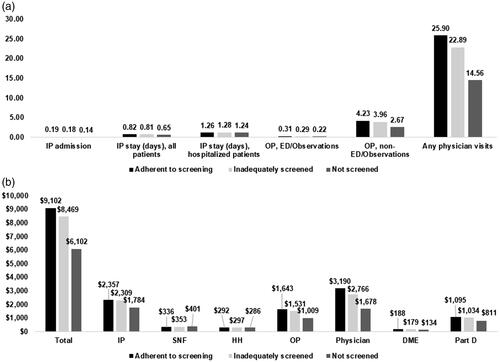

Of 895,846 eligible individuals, 13.2% were adherent to screening, 53.4% were inadequately screened, and 33.4% were not screened. Compared with those not screened, adherent or inadequately screened individuals were more likely to be female, White and have comorbidities. These individuals also used more healthcare services, generating higher Medicare costs. For example, physician visits were 14.6, 22.9 and 25.9 PPPY and total Medicare costs were $6102, $8469 and $9102 PPPY for those not screened, inadequately screened and adherent, respectively.

Conclusions

In Medicare beneficiaries at average risk, adherence to CRC screening was low, although the rate might be underestimated due to lack of early Medicare data. The link between HCRU and screening status suggests that screening initiatives independent of clinical visits may be needed to reach unscreened or inadequately screened individuals.

1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United StatesCitation1. The incidence of CRC increases with age; new cases per 100,000 were 121.4 for ages 65–69 years and increased to 237.9 for ages 80–84 years during 2012–2016Citation2. Adherence to CRC screening guidelines may enable early detection and diagnosis of the disease as well as preventing the incidence of CRC by detection and removal of benign precursor lesions (e.g. adenomas, sessile serrated polyps)Citation3, reducing the mortality rate with effective treatmentCitation4,Citation5. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends CRC screening for all adults aged 50 to 75 yearsCitation6.

Adherence rates for CRC screening vary by age of eligible population, CRC screening modality, definitions of adherence and study design. In a study using Medicare data to examine CRC screening adherence with a backward longitudinal design, the 10 year up-to-date adherence for the 2010 cohort was 25.7, 20.9, and 15.2% for those aged 76–80, 81–85, and 86–90 years, respectivelyCitation7. Another study used data from commercial health plans to estimate CRC screening adherence with a forward longitudinal design and reported that, among people who turned 50 years old from 2000 to 2004, overall adherence was 64.3% in the following 10 yearsCitation8.

Medicare is the federal health insurance program mainly for people 65 years and older. In 2019, Medicare covered about 53 million beneficiaries 65 years and olderCitation9. The large sample with Part B coverage on CRC screening enabled us to examine longitudinal adherence in older Medicare beneficiaries at average risk for CRC. To reflect current clinical practices, we applied a forward longitudinal design to estimate the incident adherence rate and screening utilization pattern from 2009 to 2018 among those due for CRC screening at the beginning of 2009. This study had two objectives: (1) to examine CRC screening adherence patterns in Medicare beneficiaries aged 66–75 years at average risk for CRC and factors associated with adherence; and (2) to estimate healthcare resource utilization (HCRU) and Medicare costs over 10 years, from 2009 to 2018, by screening patterns.

2. Methods

2.1. Data source and study population

We used 2007–2018 20% Medicare random sample data, including enrollment information, demographic characteristics, and medical claims from Parts A, B and D. To have a population representative of US older adults with 10 years’ follow-up, the study population included Medicare beneficiaries aged 66–75 years at average risk for CRC and covered under the Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) plan. We defined Medicare beneficiaries at average risk for CRC based on American Cancer Society guidelinesCitation10, as well as published studies of the Medicare populationCitation7,Citation11–15. In this study, we defined average risk as no personal history of CRC, polyps or inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis or Crohn disease); no confirmed or suspected hereditary CRC syndrome, such as familial adenomatous polyposis or Lynch syndrome (hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer).

2.2. Study design and study sample

This was a retrospective, longitudinal cohort design with 10 years’ follow-up that assumed that selected individuals were due for CRC screening beginning in 2009. Therefore, the study sample included average-risk Medicare FFS beneficiaries if they: (1) were aged 66–75 years on 1 January 2009; (2) were continuously enrolled in Medicare Parts A and B from 2008 to 2018; (3) had no history of CRC, polyps, inflammatory bowel disease or hereditary CRC syndrome in 2008; (4) were not admitted to hospice in 2008 to 2018; and (5) were not screened for CRC using colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy from 2007 to 2008. The baseline year (2008) was used to define comorbidities and high-risk events. Screening patterns, HCRU and Medicare costs were determined in the 10 year follow-up period, 2009–2018. This study was originally approved as research eligible for expedited review. We have IRB review and approval as exempt. We used Medicare claims data in this analysis. All data were anonymized and without any personal identification information. Results were presented for overall or groups (e.g. age, sex, race groups). Therefore, informed consent was not applied.

2.3. Defining CRC screening and high-risk diseases for exclusion

Screenings for CRC were identified by Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes (Supplementary Appendix A). CRC screening modalities included colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy, fecal immunochemical test or guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (FIT/gFOBT), and multitarget stool DNA test (mt-sDNA). For colonoscopy, we did not distinguish between screening and diagnostic. The claim sources to identify CRC screening were Medicare Part A outpatient and Part B claims. High-risk diseases for exclusion were considered if an individual had at least one of these claims for CRC, polyps, inflammatory bowel disease or hereditary CRC syndrome. The CPT, HCPCS, and International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) and ICD-10-CM diagnosis or procedure codes are listed in Supplementary Appendix B.

2.4. CRC screening utilization patterns with regard to adherence

Individuals were categorized as adherent to screening based on the USPSTF recommendations: colonoscopy every 10 years, flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5 years, mt-sDNA testing every 3 years or at least eight fecal FIT/gFOBT tests over the 10 year period. Individuals were categorized as not screened if no tests were observed in the 10 year period and as inadequately screened if testing occurred in the 10 year period but not often enough to qualify as adherence.

We assumed that CRC screening was due in 2009 and checked if there were any tests in each year of the 10 year follow-up period. We considered more than 90 claim-based algorithms aligning with the USPSTF recommendations. Some examples of adherence scenarios are described in the Supplemental Methods (definition of adherent to screening).

2.5. Defining baseline demographic characteristics and comorbid conditions

Patient baseline characteristics included age on 1 January 2009 (66–69 and 70–75 years); sex; race/ethnicity (White, Black, Asian, Hispanic, other race); region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West, missing); and Medicare/Medicaid dual-eligibility status during baseline (yes/no). Patient baseline clinical conditions included a continuous variable for the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)Citation16 and presence of comorbid conditions at baseline (yes/no). Patient baseline comorbid conditions were defined by at least one inpatient, skilled nursing facility (SNF), home health or hospice claim; two outpatient, Part B physician visits; or durable medical equipment (DME) claims in any position at least 30 days apart within a year. The ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes for these comorbid conditions are listed in Supplementary Appendix C; they included arteriosclerotic heart disease, heart failure, cerebrovascular accident/transient ischemic attack, peripheral vascular disease, other cardiac disease, diabetes, anemia, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, chronic kidney disease (excluding dialysis), cancer (excluding nonmelanoma skin cancer), liver disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and gastrointestinal bleeding.

2.6. Defining long-term HCRU and Medicare costs

Long-term HCRU during the 10 year follow-up was identified for all-cause hospitalizations, outpatient visits, emergency department (ED) visits/observational stays and physician visits. Measures of hospitalization included number of all-cause admissions per person per year (PPPY) and total hospital length of stay in days PPPY for the entire study sample and hospitalized patients only. Outpatient visits, ED visits/observational stays and physician visits were measured as total number of visits PPPY.

Medicare costs were defined by Medicare payment. We used standard analytical file (SAF) Parts A and B claims data to calculate total Medicare costs, including Part A inpatient and outpatient costs (including outpatient ED costs), Part A other costs (SNF, home health agency and hospice), and Part B costs for physician visits and DME. Medication cost in Part D claims was also included in the total Medicare costs. Medicare costs were adjusted to 2018 US dollars and calculated as $PPPY for the 10 year follow-up.

2.7. Statistical methods

For patient baseline characteristics, we reported frequency and percentage for categorical variables; the χ2 test was used to compare differences between CRC screening patterns. Adjusted odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of adherent to screening or inadequately screened versus not screened were estimated using multivariate logistic regression controlling for age, sex, race/ethnicity, CCI and comorbidities. Mean, standard deviation (SD), median, interquartile range (IQR) and χ2 p values were reported for long-term HCRU and Medicare costs PPPY.

Analyses were performed in SAS, version 9.4, during 2020–2021.

3. Results

3.1. Cohort selection and CRC screening utilization patterns with regard to adherence

In total, 895,846 eligible individuals were selected for the final sample from more than 2.2 million Medicare FFS beneficiaries. Sample selection with inclusions and exclusions is shown in Supplemental Figure 1. CRC screening patterns in the 10 year period by demographic characteristics and comorbid conditions are presented in . Overall, 13.2% were adherent to screening, 53.4% were inadequately screened and 33.4% were not screened. Persons in younger age-groups (66–69 years vs. 70–75 years) and females had higher rates of adherence to screening and inadequate screening and lower rate of no screening than their counterparts. Among race/ethnicity, White individuals had the highest rate of adherence to screening (13.3%) and inadequate screening (53.9%) and the lowest rates of no screening (32.8%); Hispanic individuals had the lowest rate of adherence to screening (7.8%) and inadequate screening (43.2%), and the highest rate of no screening (48.9%). Persons with dual-eligible Medicare/Medicaid had a low rate of adherence to screening (9.4%) and a higher rate of no screening (44.4%). By baseline comorbid condition, persons with gastrointestinal bleeding had the highest rate of adherence to screening (19.2%) and inadequate screening (67.1%), and the lowest rate of not screened (13.7%), followed by persons with liver disease (17.4% adherent to screening, 61.6% inadequately screen and 21.0% not screened) and persons with cancer (16.3%, 60.2% and 23.5%).

Table 1. Distribution of CRC screening patterns over a 10 year period by demographic characteristics and comorbid conditions.

3.2. Characteristics by and factors associated with CRC screening patterns

In , we present characteristic distributions by CRC screening patterns, ORs of adherence to screening and inadequate screening by demographic characteristics and clinical factors. Compared with those not screened, individuals adherent to screening or inadequately screened were more likely younger, female and White, with a higher mean CCI score and higher prevalence of baseline comorbidities. For example, the OR of adhere to screening versus no screening was 1.37 and OR of inadequately screened versus no screening was 1.49 for individuals aged 66 to 69 years reference to those 70–75 years. Compared with those of White race, individuals who were Black, Asian and Hispanic had the following ORs of adhere to screening versus no screening: 0.82, 0.68 and 0.51, respectively. Individuals with the following comorbid conditions were more likely to adhere to screening versus no screening: hyperlipidemia (OR, 3.30; 95% CI, 3.22–3.38), gastrointestinal bleeding (OR, 3.14; 95% CI, 3.06–3.23), cancer (OR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.88–1.96), liver disease (OR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.62–1.74), and anemia (OR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.49–1.54). Similarly, individuals with the following comorbid conditions were also more likely to be inadequately screened versus not screened: hyperlipidemia (OR, 2.68; 95% CI, 2.64–2.72), gastrointestinal bleeding (OR, 2.74; 95% CI, 2.68–2.80), cancer (OR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.68–1.73), liver disease (OR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.45–1.52) and anemia (OR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.45–1.48).

Table 2. Characteristic distribution by CRC screening pattern and odds ratios of those adherent to screening and inadequately screened.

3.3. Long-term HCRU and Medicare costs by CRC screening patterns with regard to adherence

presents HCRU and Medicare costs by CRC screening pattern with regards to adherence. Among Medicare beneficiaries at average risk for CRC, those adherent to screening or inadequately screened used more healthcare services and therefore had higher Medicare costs. For example, mean numbers of physician visits over 10 years were 25.9, 22.9 and 14.6 PPPY; total mean Medicare costs over 10 years were $9102, $8469 and $6102 PPPY for adherent to screening, inadequately screened and not screened, respectively. For those adherent to screening, the most expensive PPPY spending was physician visits ($3190), followed by hospitalization ($2357), outpatient ($1643) and pharmacy ($1095). The spending pattern was similar for those who were inadequately screened. For those who were not screened, the most expensive PPPY spending was hospitalization ($1784), followed by physician visits ($1678). More statistics of HCRU and costs overall and by CRC screening pattern are presented in .

Figure 1. Healthcare resource utilization and Medicare costs over 10 years by colorectal cancer screening pattern. (a). Healthcare resource utilization measured as number of admissions, number of IP stay in days or number of visits PPPY; all p values were <.0001 by screening patterns. (b) Mean Medicare cost measured as Medicare paid amount in 2018 US $PPPY; all p values were <.0001 by screening patterns. Abbreviations. HCRU, Healthcare resource utilization; PPPY, Per person per year; IP, Inpatient; OP, Outpatient; ED, Emergency department; SNF, Skilled nursing facility; HH, Home health; DME, Durable medical equipment; Part D, Medicare prescription drug.

Table 3. More statistics of healthcare resource utilization and Medicare cost over 10 years by CRC screening pattern.

4. Discussion

In this retrospective cohort study using a prospective longitudinal design of Medicare FFS beneficiaries 66–75 years in 2009 at average risk for CRC, we found that the overall adherence rate to the USPSTF screening recommendations was 13.2%, inadequate screening was 53.4% and no screening was 33.4% during the 10 year follow-up period, 2009–2018. The overall adherence rate in our study was lower than that in other studies. In a previous analysis of a similar population using a 5% Medicare random, noncancer sample conducted by Bian et al., the overall adherence rates to screening in 2010 were 25.7%, 20.9% and 15.2% for ages 76–80, 81–85 and 86–90 years, respectivelyCitation7. The different results of these two studies might be due to differences in design. Bian’s study used a retrospective longitudinal design and reported the 10 year up-to-date adherence rate; our study used a prospective longitudinal design and reported adherence based on incident screening over the 10 year follow-up. In another study using data from commercial health plans to examine CRC screening adherence, Cyhaniuk and Coombes reported adherence of 64.3% over the 10 year follow-up for persons who turned the age of 50 years during 2000 to 2004Citation8. The prospective longitudinal design of Cyhaniuk and Coombes’s study was similar to that of our study. The main reason for the difference in adherence may be due to differences in the study population reflected in the age groups. In addition, our claim-based algorithms of adherence had some differences, as we described in the Methods section, which may be reflected in the rate of inadequate screening: 53.4% in our study versus 11.9% in Cyhaniuk and Coombes’s studyCitation8.

Our study found racial and ethnic differences in CRC screening adherence with lower rates of screening adherence and higher rates of no screening among Black, Asian and Hispanic individuals compared with White individuals. This finding was consistent with those of Bian’s study, in which the overall adherence rates were 22.2%, 15.7% and 16.1% for non-Hispanic White, Black and other race/ethnicity patients, respectivelyCitation7. This racial disparity in CRC screening adherence may be associated with racial differences in use of primary care and access to preventive health servicesCitation17. For example, a study found that Asian patients in a university study sample were less likely to have a primary care provider and routine cancer screeningsCitation18. A study on the association between simulated patient race/ethnicity with scheduling of primary care appointments showed that Black and Hispanic callers might experience a barrier to timely access to primary careCitation19; Asian individuals had lower rates of getting preventive care, although they had higher rates of insurance coverageCitation20.

In the adjusted analysis, we found that the following factors were significantly associated with adherence to screening or inadequate screening versus no screening: younger age, female sex, White race, and baseline comorbid conditions of hyperlipidemia, gastrointestinal bleeding, cancer, liver disease and anemia. Individuals with these baseline conditions might have more frequent clinical or physician visits and therefore might receive more recommended preventive care. Our results on HCRU and Medicare costs by CRC screening pattern showed that individuals classified as adherent to screening or inadequately screened used more healthcare services and therefore had higher Medicare spending. This finding may also reflect the association of CRC screening with clinical or physician visits due to complicated medical conditions.

Our study had some limitations. First, because of lack of Medicare data from the early years, we might have misclassified an individual who was adherent to screening as inadequately screened. We assumed our study patients were due for CRC screening in 2009 by retrospectively examining all available 20% Medicare data from 2007. For example, if a person underwent colonoscopy in 2003 (we could not find this test because of data limitations) and another screening in 2013, this person was classified as inadequately screened because we assumed the test was due in 2009 for the entire study sample. Therefore, the rate of adherence to screening may be underestimated in our study. Second, in the adjusted analysis of association of adherence with different factors, residual confounding may have occurred because it was an observational study using claims data. Therefore, the association should not be classified as a causal relationship. Last, these findings were obtained from Medicare beneficiaries aged 66–75 years and might not be generalizable to the US general population or other populations.

Findings from this study have important policy implications, despite the limitations. We found that not only was the CRC screening adherence rate low in the study population but also one-third of the study population was unscreened in the most recent 10 years, 2009–2018. In Healthy People 2030, the US government targets 74.4% of adults for CRC screening, based on the up-to-date rate of 65.2% in 2018Citation2,Citation21. Out study results provide evidence of gaps between real-world CRC screening and the government’s target. In our study, the rate of adults unscreened over the 10 years for Medicare-only beneficiaries was 32.7%; the rate of those unscreened for Medicare/Medicaid dual-eligible beneficiaries was 44.4%. State-specific law and policy on insurance coverage for Medicaid beneficiaries may have been associated with the high unscreened rate in Medicare/Medicaid dual-eligible beneficiaries. There were several updates to Medicare CRC screening coverage policy in our study period of 2009–2018. On 1 January 2011, Medicare policy eliminated cost-sharing for preventive services such as colonoscopyCitation22. On 9 October 2014, Medicare began reimbursing for the new screening modality of mt-sDNACitation23. Today, under the original Medicare policy, beneficiaries pay nothing for these tests if their health provider or doctor accepts MedicareCitation24. Effective 19 January 2021, Medicare initiated a new Part B coverage on the blood-based biomarker test for the purpose of CRC screening test once every 3 years with certain requirementsCitation25. To increase adherence to screening, it may be important for primary care doctors to understand insurance coverage policy as to provider referral and follow-up and increase patient awareness of all screening modalities.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, in Medicare beneficiaries at average risk, adherence to CRC screening was low, although the rate may have been underestimated due to lack of early Medicare data. The link between HCRU and screened status suggests that screening initiatives independent of clinical visits may be needed to reach those who are unscreened or inadequately screened.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was supported by Exact Sciences, Madison, Wisconsin. The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not reflect those of the funding or data sources. The funding sponsor had no role in study design; data collection, analyses or interpretation; manuscript preparation; or the decision to publish the results.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

L.-A.M.-W. has disclosed that she is an employee and stockholder of Exact Sciences. D.A.F. has disclosed that she is a former faculty member of Duke University, current employee of Eli Lilly, and consultant for Exact Sciences, Freenome and Guardant Health. No potential conflict of interest was reported by S.L. or H.G. CMRO peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

S.L.: conception and design, interpretation of the data, drafting of paper and revising. L.-A.M.-W.: conception and design, interpretation of the data, revising. H.G.: analysis and interpretation of the data. D.A.F.: conception and design, interpretation of the data, revising. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Data availability statement

All data that support the findings of this study are included within the article (and any supplementary information files). Because analytic data files for this manuscript include restricted Medicare data, they are subject to data use agreements with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and, as such, not available for distribution.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (86.7 KB)Appendix_C_-_Codes_for_comorbid_conditions.docx

Download MS Word (15.9 KB)Appendix_B_-_Codes_for_excluding_high-risk_diseases.docx

Download MS Word (14.9 KB)Appendix_A_-_Codes_for_CRC_screenings_and_tests.docx

Download MS Word (13.2 KB)Supplemental_Method.docx

Download MS Word (13.7 KB)Acknowledgements

The study results were presented at the American College of Gastroenterology Annual Meeting; 2021 Oct 22–27; Mandalay Bay Resort, Las Vegas, Nevada.

The authors thank Chronic Disease Research Group (CDRG) colleagues Kimberly Nieman for project management and administration and Anna Gillette for manuscript editing (funding through Exact Sciences).

References

- American Cancer Society. Key statistics for colorectal cancer [Internet] [cited 2021 Jul 6]. Available from: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/colon-rectal-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

- American Cancer Society. Colorectal cancer facts & figures 2020–2022 [Internet] [cited 2021 Jul 6]. Available from: https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/colorectal-cancer-facts-figures.html

- Bone RH, Cross JD, Dwyer AJ, et al. A path to improve colorectal cancer screening outcomes: faculty roundtable evaluation of cost-effectiveness and utility. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(6 Suppl):S123–S143.

- Lin JS, Piper MA, Perdue LA, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive services task force (evidence syntheses, No. 135. AHRQ Publication No. 14-05203-EF-1). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2016.

- Zauber A, Knudsen A, Rutter CM, et al. Evaluating the benefits and harms of colorectal cancer screening strategies: a collaborative modeling approach. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2015.

- US Preventive Services Taskforce. Final recommendation statement. Colorectal cancer: screening [Internet] [cited 2021 Jul 6]. Available from: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/colorectal-cancer-screening#fullrecommendationstart

- Bian J, Bennett C, Cooper G, et al. Assessing colorectal cancer screening adherence of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries age 76–95 years. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(6):e670–e680.

- Cyhaniuk A, Coombes ME. Longitudinal adherence to colorectal cancer screening guidelines. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22(2):105–111.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2019 Medicare sections [Internet] [cited 2021 Jul 8]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-systems/cms-program-statistics/2019-medicare-sections

- American Cancer Society. American Cancer Society guideline for colorectal cancer screening [Internet] [cited 2021 Jul 27]. Available from: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/colon-rectal-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/acs-recommendations.html

- Song LD, Newhouse JP, Garcia-De-Albeniz X, et al. Changes in screening colonoscopy following Medicare reimbursement and cost-sharing changes. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(4):839–850.

- Davis MM, Renfro S, Pham R, et al. Geographic and population-level disparities in CRC testing: a multilevel analysis of Medicaid and commercial claims data. Prev Med. 2017;101:44–52.

- O’Leary MC, Lich KH, Gu Y, et al. CRC screening in newly insured Medicaid members: a review of concurrent federal and state policies. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):298.

- Bonafede MM, Miller JD, Pohlman SK, et al. Breast, cervical, and CRC screening: patterns among women with Medicaid and commercial insurance. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(3):394–402.

- Pyenson B, Pickhardt PJ, Sawhney TG, et al. Medicare cost of CRC screening: CT colonography vs. optical colonoscopy. Abdom Imaging. 2015;40(8):2966–2976.

- Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson Comorbidity Index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(6):676–682.

- American College of Physicians. Racial and ethnic disparities in health care, updated 2010 [Internet] [cited 2021 Aug 18]. Available from: https://www.acponline.org/acp_policy/policies/racial_ethnic_disparities_2010.pdf

- Focella ES, Shaffer VA, Dannecker EA, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in the use of primary care providers and preventive health services at a Midwestern University. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2016;3(2):309–319.

- Wisniewski JM, Walker B. Association of simulated patient race/ethnicity with scheduling of primary care appointments. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(1):e1920010.

- Mead H, Cartwright-Smith L, Jones K., et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in U.S. health care: a chartbook [Internet]. The Commonwealth Fund; 2008 [cited 2021 Aug 18]. Available from: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/documents/___media_files_publications_chartbook_2008_mar_racial_and_ethnic_disparities_in_u_s__health_care__a_chartbook_mead_racialethnicdisparities_chartbook_1111_pdf.pdf

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, US Department of Health and Human Services. Increase the proportion of adults who get screened for colorectal cancer — C-07. Healthy People 2030 [Internet] [cited 2021 Aug 19]. Available from: https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/cancer/increase-proportion-adults-who-get-screened-colorectal-cancer-c-07

- Cassidy A. Preventive services without cost sharing. Health policy brief: preventive services without cost sharing [Internet]. Health Aff; 2010 [cited 2021 Aug 19]. Available from: 10.1377/hpb20101228.861785/full/health-affairs-policy-brief-preventive-services-without-costsharing.pdf

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Decision memo for screening for colorectal cancer – stool dna testing (CAG-00440N) [Internet] [cited 2021 Aug 19]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=277

- Medicare Coverage for Cancer Prevention and Early Detection. [cited 2022 Oct 17]. Available from: https://www.cancer.org/treatment/finding-and-paying-for-treatment/understanding-health-insurance/government-funded-programs/medicare-medicaid/medicare-coverage-for-cancer-prevention-and-early-detection.html

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. National coverage determination (NCD) 210.3 – screening for colorectal cancer (CRC) – blood-based biomarker tests [Internet] [cited 2022 Sep 27]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/mm12280.pdf