Dear Editor,

We appreciate the important comments and suggestions provided by Dr. Pham et al.Citation1 and thank them for their interest in our study regarding the impact of switching to infliximab (IFX) biosimilars on treatment patterns among United States (US) veteransCitation2. Our responses to the points raised are included below.

First, regarding the comment from Dr. Pham et al. about censoring and the resulting shorter follow-up in the continuers cohort, we would like to note that we used switching to any innovator drug (i.e. either innovator IFX or another biologic) as the main outcome of interest for our study since it represented a switch driven by the physician or patient (presumably with the intention of remaining on the biosimilar), whereas switching from innovator IFX to a biosimilar would likely represent a non-medical switch (e.g. systemic switching based on Veteran Health Administration [VHA] policy, as mentioned by Dr. Pham et al.). While we recognize that censoring continuers when they switch to a biosimilar may have resulted in fewer switching events in the continuer cohort, similar approaches were also previously used by Lund et al. and Hellström et al. to avoid conditioning on future exposure to define study cohortsCitation3,Citation4. The approach used also allowed patients to contribute to both the switcher and continuer cohorts, thus allowing us to focus on switches driven by the physician or patient rather than non-medical switches (the latter being used to define our cohorts instead). Additionally, censoring was adjusted for in our study by using survival analyses (i.e. Kaplan-Meier curves and Cox models), thus accounting for differences in follow-up length between the two cohorts.

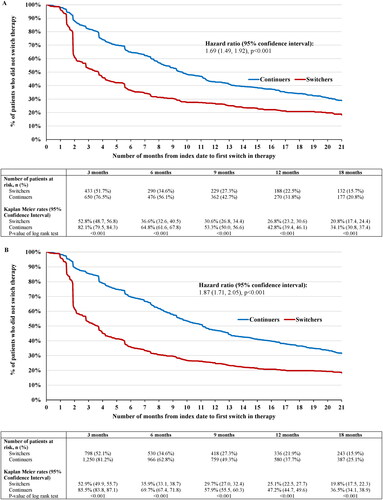

For the benefit of the readers and to assess the robustness of our results, we conducted a sensitivity analysis where the switch to a biosimilar was considered an eligible event instead of a censoring outcome in the continuer cohort. Results show that even when accounting for switches to IFX biosimilar in the continuer cohort (thus adding switching events in the continuer cohort), switchers were still 1.69–1.87-times more likely to switch biologics compared to continuers. In particular, among the incident population (N = 838 switchers, N = 849 continuers), 653 (77.8%) switchers and 539 (63.5%) continuers switched post-index to another innovator biologic (including innovator IFX) or biosimilar (hazard ratio [HR; 95% confidence interval (CI)] = 1.69 [1.49, 1.92]; p < .001; ). Among the prevalent population (N = 1531 switchers, N = 1539 continuers), 1215 (79.3%) switchers and 987 (64.1%) continuers switched post-index to another innovator biologic (including innovator IFX) or biosimilar (HR [95% CI] = 1.87 [1.71, 2.05]; p < .001; ). Therefore, while the magnitude of the difference observed between the two cohorts is smaller than in the original findings of the study (HRs of 4.99–6.51 versus 1.69–1.87), the estimates still show a sizable statistically significant association between being in the switcher cohort and having a switching event post-index. Furthermore, our findings remain consistent with other published real-world studies, in that patients who switch to biosimilars have higher rates of discontinuation and subsequent change in therapy compared to patients who continue with innovator biologics, and that the majority of these subsequent changes in therapy are a return to the innovator biologicCitation5–10.

Figure 1. Adjusted Kaplan Meier curves of (A) time to switch among the incident population and (B) time to switch among the prevalent population.

Second, related to the validation of the results discussed by Dr. Pham et al., we recognize that our study was based on standardized data from the Veterans Affairs (VA) Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) alone and did not include a chart review component, which represents a limitation of the study that may warrant further research. Notwithstanding, the VA CDW is a common and reliable source of data that has been used in numerous real-world studies for a variety of outcomesCitation11–13. Additionally, given that the majority of switches in the current study are to biologics administered intravenously, most switches should be captured directly in the electronic medical records of the CDW data used for this study, which minimizes the potential for misclassification of patients switching/not switching and mitigating the impact that this limitation may have on the results. Lastly, both VA Institutional Review Board and Research & Development Committee vetted the study for conflicts of interest before its approval.

Regarding the comment by Dr. Pham et al. on the efficacy between biosimilars and originator biologics, as stated in our paper, we agree that there are no clinically meaningful differences in efficacy and safety between originator biologics and biosimilars, as shown in the NOR-SWITCH trialCitation14 and in other randomized clinical trialsCitation15,Citation16. However, outcomes have differed in the real-world setting, where multiple studies of IFX and other biologics have reported trends in discontinuation and switch that are similar to our original findingsCitation5–10,Citation17,Citation18. As noted in our paper, the switch itself is likely to be the main driver of the negative outcomes, as opposed to the direction of the switch (i.e. from innovator to biosimilar or vice versa), particularly for patients who were stable for a long period of time on the previous medicationCitation2. One potential reason for the negative outcome that is often cited in the literature and was also cited in our paper is the nocebo effect, where patients have been observed to discontinue biosimilars despite no change in disease activity and/or lack of objective adverse events, suggesting subjective reasons for treatment discontinuation rather than efficacy-related reasonsCitation5,Citation8,Citation9,Citation19,Citation20. Additionally, we discuss in detail the impact of non-medical switching on non-health outcomes, such as healthcare resource utilization (HRU) and costs. There is ample literature describing the higher HRU and costs associated with non-medical switches in generalCitation21,Citation22, and for those switching from innovator biologics to biosimilars specifically in real-world clinical practiceCitation7,Citation23,Citation24. As mentioned in our paper, much of these excess HRU and costs are associated with the measures intended to mitigate the outcomes of non-medical switchingCitation2. For instance, in a systematic literature review of real-world studies conducted by Liu et al., non-medical switching from innovator biologics to biosimilars was found to be associated with increased HRU related to program setup and administration, additional monitoring, dose adjustments, and patient/healthcare professional education to manage expectations like the nocebo effectCitation24. In a separate systematic literature review by Hillhouse et al., all included studies found that non-medical switching was associated with significant or numerical increases in HRUCitation25. Therefore, while innovator biologics and biosimilars do not differ in clinical efficacy or safety, non-medical switching between them in the real-world setting can result in negative economic outcomes that may offset the lower drug costs of biosimilars. As such, this information is important to consider for both healthcare systems and policy makers when planning non-medical switching.

Once again, we thank Dr. Pham et al. for their comments and suggestions, as well as their interest in our study. We appreciate their input and the common interest they share in gaining a better understanding regarding the use of biosimilars and their effectiveness in the treatment of chronic inflammatory diseases.

References

- Pham C, Tomcsanyi KM, Waljee AK, et al. Re: Lin I, Melsheimer R, Bhak RH, Lefebvre P, DerSarkissian M, Emond B, Lax A, Nguyen C, Wu M, Young-Xu Y; Impact of switching to infliximab biosimilars on treatment patterns among US veterans receiving innovator infliximab. Curr Med Res Opin. 2022;16:1–2.

- Lin I, Melsheimer R, Bhak RH, et al. Impact of switching to infliximab biosimilars on treatment patterns among US veterans receiving innovator infliximab. Curr Med Res Opin. 2022;38(4):613–627.

- Lund JL, Horvath-Puho E, Komjathine Szepligeti S, et al. Conditioning on future exposure to define study cohorts can induce bias: the case of low-dose acetylsalicylic acid and risk of major bleeding. Clin Epidemiol. 2017;9:611–626.

- Hellstrom PM, Gemmen E, Ward HA, et al. Switching from originator infliximab to biosimilar versus continuing on originator in inflammatory bowel disease: results from the observational Project North study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2022;14:1–8.

- Avouac J, Molto A, Abitbol V, et al. Systematic switch from innovator infliximab to biosimilar infliximab in inflammatory chronic diseases in daily clinical practice: the experience of Cochin University Hospital, Paris, France. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2018;47(5):741–748.

- Bakalos G, Zintzaras E. Drug discontinuation in studies including a switch from an originator to a biosimilar monoclonal antibody: a systematic literature review. Clin Ther. 2019;41(1):155–173 e13.

- Phillips K, Juday T, Zhang Q, et al. SAT0172 economic outcomes, treatment patterns, and adverse events and reactions for patients prescribed infliximab or ct-p13 in the Turkish population. Annals Rheumatic Diseases. 2017;76(Suppl 2):835.1–835.

- Scherlinger M, Germain V, Labadie C, et al. Switching from originator infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 in real-life: the weight of patient acceptance. Joint Bone Spine. 2018;85(5):561–567.

- Tweehuysen L, van den Bemt BJF, van Ingen IL, et al. Subjective complaints as the main reason for biosimilar discontinuation after open-label transition from reference infliximab to biosimilar infliximab. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(1):60–68.

- Yazici Y, Xie L, Ogbomo A, et al. Analysis of real-world treatment patterns in a matched rheumatology population that continued innovator infliximab therapy or switched to biosimilar infliximab. Biologics. 2018;12:127–134.

- Backus LI, Belperio PS, Loomis TP, et al. Impact of race/ethnicity and gender on HCV screening and prevalence among U.S. veterans in department of veterans affairs care. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(Suppl 4):S555–S61.

- Baum A, Schwartz MD. Admissions to veterans affairs hospitals for emergency conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;324(1):96–99.

- Lisi AJ, Brandt CA. Trends in the use and characteristics of chiropractic services in the department of veterans affairs. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016;39(5):381–386.

- Jorgensen KK, Olsen IC, Goll GL, et al. Switching from originator infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 compared with maintained treatment with originator infliximab (nor-SWITCH): a 52-week, randomised, double-blind, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10086):2304–2316.

- Smolen JS, Choe JY, Prodanovic N, et al. Safety, immunogenicity and efficacy after switching from reference infliximab to biosimilar SB2 compared with continuing reference infliximab and SB2 in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results of a randomised, double-blind, phase III transition study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(2):234–240.

- Yoo DH, Prodanovic N, Jaworski J, et al. Efficacy and safety of CT-P13 (biosimilar infliximab) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: comparison between switching from reference infliximab to CT-P13 and continuing CT-P13 in the PLANETRA extension study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(2):355–363.

- Alten R, Neregard P, Jones H, et al. SAT0161 preliminary real world data on switching patterns between etanercept, its recently marketed biosimilar counterpart and its competitor adalimumab, using Swedish prescription registry. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2017;76(Suppl):2.

- Madenidou A, Jeffries A, Varughese S, et al. Switching patients with inflammatory arthritis from Etanercept (Enbrel®) to the biosimilar drug, SB4 (Benepali®): a single-Centre retrospective observational study in the UK and a review of the literature. Mediterr J Rheumatol. 2019;30(Suppl 1):69–75.

- Boone NW, Liu L, Romberg-Camps MJ, et al. The nocebo effect challenges the non-medical infliximab switch in practice. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;74(5):655–661.

- Mahmmod S, Schultheiss JPD, van Bodegraven AA, et al. Outcome of reverse switching from CT-P13 to originator infliximab in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;27(12):1954–1962.

- Liu Y, Skup M, Lin J, et al. Impact of non-medical switching on healthcare costs: a claims database analysis. Value in Health. 2015;18(3):A252.

- Weeda ER, Nguyen E, Martin S, et al. The impact of non-medical switching among ambulatory patients: an updated systematic literature review. J Mark Access Health Policy. 2019;7(1):1678563.

- Gibofsky A, Skup M, Yang M, et al. Short-term costs associated with non-medical switching in autoimmune conditions. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2019;37(1):97–105.

- Liu Y, Yang M, Garg V, et al. Economic impact of non-medical switching from originator biologics to biosimilars: a systematic literature review. Adv Ther. 2019;36(8):1851–1877.

- Hillhouse E, Mathurin K, Bibeau J, et al. The economic impact of originator-to-Biosimilar non-medical switching in the Real-World setting: a systematic literature review. Adv Ther. 2022;39(1):455–487.