Abstract

Objective

The World Health Organization issued a call to action for primary care to lead efforts in managing noncommunicable diseases, including osteoporosis. Although common, osteoporosis remains underdiagnosed and undertreated. Primary care practitioners (PCPs) are critical in identifying individuals at risk for osteoporosis and osteoporotic fractures; however, recent advances in assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of osteoporosis have not been incorporated into clinical practice in primary care due to numerous reasons including time constraints and insufficient knowledge. To close this gap in clinical practice, we believe PCPs need a practical strategy to facilitate osteoporosis assessment and management that is easy to implement.

Methods

In this article, we consolidate information from various global guidelines and highlight areas of agreement to create a streamlined osteoporosis management strategy for a global audience of PCPs.

Results

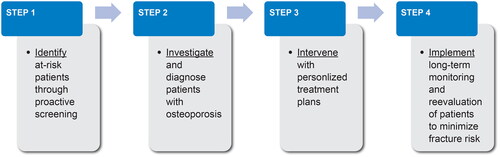

We present a systematic approach to facilitate osteoporosis assessment and management that includes four steps: (1) identifying patients at risk through proactive screening strategies, (2) investigating and diagnosing patients, (3) intervening with personalized treatment plans, and (4) implementing patient-centered strategies for long-term management and monitoring of patients.

Conclusion

Primary care has a central role in ensuring the incorporation of key elements of holistic care as outlined by the World Health Organization in managing noncommunicable diseases including osteoporosis; namely, a people-centered approach, incorporation of specialist services, and multidisciplinary care. This approach is designed to strengthen the health system’s response to the growing osteoporosis epidemic.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

Osteoporosis is a chronic condition associated with aging in which bones become “porous” and weak, and are more likely to break (i.e., fracture) even with minimal trauma such as tripping or falling from a standing height. A broken bone is a serious condition that not only affects daily activities, but can also lead to reduced quality of life, need for caregiver support, work loss, hospital and rehabilitation costs, nursing home costs, and increased mortality. Although osteoporosis is common, it is often undiagnosed or untreated, leaving many people at risk for experiencing broken bones. A broken bone increases the risk of more broken bones. Given the growing size of the aging global population, osteoporosis and the risk of broken bones represent an urgent problem and growing burden. We need ways to make it easier for primary care practitioners (PCPs), such as family physicians, internists, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and nurses, to include osteoporosis care as part of routine clinical visits. In this article, we discuss the critical role of PCPs in early detection, diagnosis, and treatment of osteoporosis as they are often the first point of contact for at-risk patients. We present a simple, four-step approach to help PCPs and patients navigate the journey from osteoporosis diagnosis to a treatment plan. The four steps are to: (1) identify at-risk patients by screening for weak bones or osteoporosis, (2) perform necessary tests to diagnose patients, (3) develop a personalized treatment plan, and (4) determine long-term strategies for managing and monitoring bone health.

Video Abstract

Thoracic endovascular aortic repair of a large, multilobulated, calcified thoracic aneurysm. Read the transcript

World Health Organization's call to action for primary care

The World Health Organization (WHO) issued a call to action for primary care to lead efforts in screening, assessing, and managing noncommunicable diseases, which are major causes of death and disability worldwideCitation1. Osteoporosis is one such disease, characterized by low bone mass, structural deterioration of bone tissue, and disruption of bone microarchitecture. Osteoporosis can lead to increased risk of osteoporotic fractures resulting from low or minimal trauma experienced upon falling from a standing height or lesser impactCitation2,Citation3. Osteoporotic fractures include fractures of the hip, spine [clinical], wrist, humerus, tibia, pelvis, and vertebral fractures with limited clinical expression and can be life-altering eventsCitation3. Given the growing size of the aging population globally, osteoporosis represents an increasing societal and economic burden worthy of dedicated focus by primary care practitioners (PCPs).

As the primary contact with patients, PCPs are uniquely positioned to identify and manage individuals at risk for osteoporosis and osteoporotic fracture. Despite this critical role, more recent advances in assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of osteoporosis are not regularly incorporated into primary care clinical practice due to multiple factors, including time constraints, insufficient knowledge, doubts about effectiveness of treatments, fear of adverse events, and misinformation. In the past, several organizations and bone-health expert groups had developed clinical guidelines for osteoporosis management; however, the guidance was not always consistent or aligned across organizations, or across countries and regions. Notably newer and/or updated guidelines from a number of organizations including the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology (AACE/ACE)Citation4, the Bone Health and Osteoporosis Foundation (BHOF; formerly the National Osteoporosis Foundation)Citation5, the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) together with the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO)Citation6, the Endocrine SocietyCitation7, and the North American Menopause Society (NAMS)Citation8 are now more aligned than previous guidelines on a number of points including criteria for patient classification by fracture risk category and recommendations on treatment plans per the risk categories. Additionally, the IOF and BHOF developed the Radically Simple ToolCitation9,Citation10, which is a simple visual to aid PCPs initiate dialogue with their patients about osteoporosis and fracture risk during medical consultations. With the aligned guidelines and the Radically Simple ToolCitation9,Citation10 now available to PCPs, this critical group of healthcare providers are well positioned to successfully take action to manage osteoporosis and lower the risk of patients suffering debilitating fractures. To this effect, we have developed a practical approach to osteoporosis assessment and management that is easy to implement in clinical practice and can guide clinical decision-making. We consolidated information from various global guidelines and highlighted areas of agreement to create a streamlined osteoporosis management strategy for a global audience of PCPs, which we have also summarized in a related video abstract (see Video Abstract). This approach incorporates the key elements outlined by the WHO; namely, a people-centered approach, incorporation of primary care and specialist services, and multidisciplinary care, and is designed to strengthen the health system’s response to the growing osteoporosis epidemic.

Osteoporosis burden

In 2000, an estimated nine million new osteoporotic fractures occurred worldwideCitation11. A more recent study that evaluated fractures at all sites and for all ages reported an estimated 178 million fractures across 204 countries and territories in 2019, with most of the fractures occurring in the elderlyCitation12.

Globally, one in three women and one in five men aged 50 years and above will suffer an osteoporotic fracture during their remaining lifetimeCitation2,Citation11,Citation13; the corresponding rates in the United States (US) are one in two women and one in four menCitation14. Osteoporotic fractures can lead to reduced quality of life, need for caregiver support, work loss, hospital and rehabilitation costs, nursing home costs, and increased mortalityCitation2,Citation4–6,Citation15–19. An analysis of Medicare data commissioned by the BHOF and conducted by the independent actuarial firm MillimanCitation15 showed that patients who suffer an osteoporotic fracture are likely to experience several other negative and costly health consequences, including hospitalizations (40% within 1 week after the fracture), subsequent bone fractures (14% within the first year following the prevalent fracture), and institutionalization in nursing care facilities (3%)Citation15. In the US, the number of hospitalizations for osteoporotic fractures (43%) exceeded those for heart attack (25%), stroke (26%), and breast cancer (6%) from 2000 to 2011Citation20 (Supplemental Figure 1 in Supplemental Material). In Europe, osteoporosis-related disability is comparable to or greater than disability due to high blood pressure–related heart disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and asthmaCitation2,Citation11. One-year mortality following hip fracture has been reported to range from 20% to 35%Citation15,Citation21.

In the US, the total annual expenditure for all osteoporosis-related fractures, including direct and indirect costs, was estimated at US$57 billion in 2018 and is projected to increase to over $95 billion in 2040Citation22. In Europe, the total annual expense for new osteoporotic fractures for five of the largest European Union (EU) countries plus Sweden (EU6) was estimated at €37.5 billion in 2017 and is projected to increase to €47.4 billion by 2030Citation23. The recent SCOPE 2021 report of osteoporosis data from 27 countries in the EU plus Switzerland and the United Kingdom (EU + 2) estimated the economic burden of fractures in 2019 to be €55.3 billionCitation24. The United Nations projects a dramatic increase in the global old-age dependency ratio (i.e. ratio of the population aged 65 years and above to the population aged 15–64 years), thus increasing the proportion of the population at risk for osteoporotic fracturesCitation25. In the EU + 2 countries, the population aged 50 years and above is projected to increase by 11.4% between 2019 and 2034 and the number of fractures in general is expected to rise by 25%Citation24,Citation26. Hip fractures, considered the most life altering and devastating of fractures, are projected to increase by 240% in women and 310% in men by 2050, globally, compared with 1990 ratesCitation27,Citation28. These regional and global projected figures are likely to increase osteoporosis-related healthcare costs.

Despite the high associated morbidity and mortality, osteoporosis remains underdiagnosed and undertreatedCitation22. Of the estimated 200 million women with an osteoporosis diagnosis globallyCitation2, fewer than 20% receive an osteoporosis diagnosisCitation2,Citation29; of the patients who receive an osteoporosis diagnosis, fewer than 35% receive treatment even after a fractureCitation30–33; and of the patients who receive treatment, fewer than 50% persist with treatment beyond 6 monthsCitation31,Citation34,Citation35 (Supplemental Figure 2 in Supplemental Material). The SCOPE 2021 report for the EU + 2 countriesCitation24 estimated that 25.5 million women and 6.5 million men had osteoporosis in 2019, with 4.3 million fractures sustained in the same year. A follow-up article on osteoporosis management in the same countries reported an average increase in the treatment gap from 55% in 2010 to 71% in 2019; 10.6 million women eligible for treatment went untreated in 2010 and this number rose to 14.0 million women in 2019Citation26.

Osteoporosis risk factors include prior fracture, age (65 years and above), low bone mineral density (BMD), parent hip fracture history, low body mass index (BMI), calcium/vitamin D deficiency, low protein intake, use of medications that may increase bone loss (e.g. glucocorticoids), inadequate physical activity, tobacco smoking, and excessive alcohol intakeCitation2,Citation4,Citation5,Citation36–39. If osteoporosis is unrecognized and left untreated, the traditional osteoporosis patient journey can often include multiple fractures across decadesCitation40. Importantly, occurrence of a recent fracture is most predictive of a second or subsequent fractureCitation15,Citation41–44. One study reported a five-fold higher risk of fracture in the first year following a prevalent fractureCitation44. Another study reported a 10% risk of recurrent fracture at year 1, 18% by year 2, and 31% by year 5Citation41. The Milliman analysisCitation15 reported that about 14% of Medicare beneficiaries who had a new osteoporotic fracture suffered one or more subsequent fractures within 12 months of the initial fracture. These findings suggest that early treatment with agents that rapidly reduce fracture risk could prevent secondary fractures in high-risk individualsCitation6,Citation43, especially in individuals aged 65 years and above who had experienced a recent hip or vertebral fractureCitation45,Citation46. In patients who have not experienced a prevalent fracture, the focus should be on proactive primary prevention, which requires screening and treating patients at risk to prevent occurrence of the first fracture.

Of note, although there is agreement within the healthcare community on the need for osteoporosis screeningCitation4,Citation5,Citation8,Citation47, the specific guidelines for screening such as patient age, frequency, and risk factors remain a point of debate among opinion leaders and health economics specialists. Despite this debate, given the high individual and societal burden that results from underdiagnosed and undertreated osteoporosis and subsequent fractures, there is a clear need for bone health working groups within the PCP communities to provide leadership consistent with WHO’s call for primary care to lead efforts in screening, assessing, and managing noncommunicable diseases.

The crucial role for primary care

Osteoporotic fractures typically present via the emergency department or orthopedic and neurosurgery services. Despite initial acute attention to the fracture, many patients fail to receive continued care beyond the fracture episodeCitation5. Moreover, the clear risk factors for osteoporosis go completely unrecognizedCitation2,Citation22,Citation29. As providers who generally have a long-term, trust-based relationship with patients, PCPs can and should play a critical role in postfracture osteoporosis assessment and management. Osteoporosis does not belong to any one specialty and, given the rising prevalence of osteoporosis and limited number of specialists in the field, primary care involvement is critical.

A growing trend is the establishment of postfracture care (PFC) or multidisciplinary osteoporosis care programs that consist of teams of healthcare providers including PCPs, specialists (orthopedic surgeons, endocrinologists, rheumatologists, geriatricians, and others), and allied healthcare workers (dietitians, nurses, nutritionists, pharmacists, and physical therapists) who work in a coordinated way to assess, diagnose, educate, and treat patients with fractures to avoid subsequent fractures. The most common PFC programs include fracture liaison services (FLSs) that focus on preventing subsequent fracturesCitation48 and geriatric/orthogeriatric services (OGSs) that focus on improving overall outcomes (morbidity, mortality, and/or physical function) for inpatients hospitalized for a fractureCitation49. PFC programs have been reported to improve patient follow-up, testing, and treatment ratesCitation48,Citation50–52; with one study demonstrating increased BMD testing from 21% to 93%, increased vitamin D assessments from 25% to 84%, increased calcium/vitamin D prescriptions from 36% to 93%, and increased osteoporosis medication prescriptions from 20% to 54%Citation51. Results from a study that explored the course of health state utility value over 3 years in patients who had experienced a recent fracture and were enrolled in an FLS suggested that although the overall change in health-related quality of life was not significant over the 3 years, significant improvements were observed at 6 and 12 months compared with baselineCitation53.

The success of PFC programs hinges on adoption of best practices by PCPs with regards to referring and receiving patients in these programs. It is important to maintain appropriate communication with patients and other members of the PFC program, maintain patients’ treatment plans, continue to conduct patients’ bone-health assessments, and continue to evaluate patients’ osteoporosis risk factors.

In areas where PFCs are not yet available, PCPs can take the initiative to establish one using the educational resources and counsel provided by a number of medical societies including the IOF’s Capture the Fracture, the IOF PFC resource center, BHOF FLS resources, BHOF FLS coding guide, American Orthopaedic Association (AOA)’s Own the Bone, American Geriatrics Society (AGS)’s CoCare model, and the Fragility Fracture Network (FFN) Clinical and Policy Toolkits. An opportunity also exists within the broader healthcare community to recommend specific actions and frameworks for different models of PFCs in order to improve patient care following a fracture.

Another avenue for enhancing osteoporosis management is for bone health organizations (e.g. IOF, BHOF, ESCEO) to develop relationships with PCP leading organizations such as the World Organization of National Colleges, Academies and Academic Associations of General Practitioners/Family Physicians (WONCA). One possibility is to establish bone health working groups on osteoporosis management under the WONCA umbrella, similar to currently existing working groups on quality, digital health, and equity. Developing multidisciplinary clinical leadership in bone health at the primary care level could also strengthen relationships with leading organizations on topics such as family medicine, nursing, and allied professions.

Four key steps to manage osteoporosis and prevent disability due to osteoporotic fractures

In , we present a schematic overview of a proposed algorithm to aid in decision-making when managing patients at risk for osteoporotic fractures. This approach includes four steps: (1) identifying patients at risk through proactive screening strategies; (2) investigating and diagnosing patients with osteoporosis based on age, fracture history, BMD and/or fracture risk score; (3) intervening with personalized treatment plans for patients diagnosed with osteoporosis or at high risk for fracture; and (4) implementing patient-centered plans for long-term monitoring and re-evaluation of patients to minimize fracture risk (see Video Abstract). We discuss implementation of this algorithm within a clinical setting and also provide sample dialogues with patients to demonstrate effective communication strategies.

Figure 1. Proposed systematic approach for diagnosing and managing patients with osteoporosis to prevent osteoporotic fractures.

Step 1: identify patients at risk for osteoporotic fractures through proactive screening

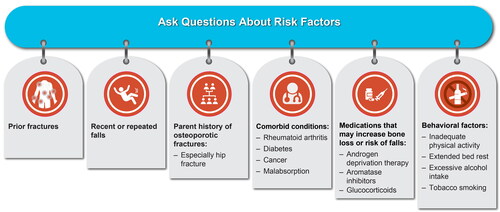

The strongest predictor of a future osteoporotic fracture is a prior osteoporotic fractureCitation4–6. Occurrence of a fracture at one anatomic site is usually an indication of systemically compromised bone quality and increases the risk of future fracture at other sitesCitation54–57; therefore, risk assessment, either in person or via virtual care (medical consultations through video calls, phone calls, emails, and text messaging) should start by eliciting a history of fracture (). According to guidance from the BHOFCitation5, AACE/ACECitation4, IOF/ESCEOCitation6, and a multi-stakeholder coalition assembled by the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research (ASBMR)Citation45, patients with a recent hip or vertebral fracture are at very high risk for fracture and should immediately proceed to a personalized treatment plan.

Figure 2. Questions to ask during routine clinic visits to identify patients with or at risk for osteoporosis and osteoporotic fractures.

Patients who do not report a recent hip or vertebral fracture should be asked follow-up questions designed to identify risk factors for osteoporosis or osteoporotic fractures (including fractures of the hip, spine, wrist, humerus, tibia, and pelvis) (). Patients who are identified as having any of the risk factors for osteoporosis or osteoporotic fractures, show signs and symptoms of a vertebral fracture and/or the risk of falling, or women who are postmenopausal should be further investigated as described in Step 2 below. Engaging with patients using appropriate language is critical. A sample dialogue between a practitioner and a 60-year old postmenopausal woman who has an annual visit is presented in Supplemental Figure 3 in Supplemental Material, Clinical Scenario 1.

Step 2: investigate and diagnose patients with osteoporosis who are at risk for osteoporotic fractures

Step 2 consists of investigating and diagnosing patients suspected to be at risk for fracture either due to age, the presence of signs and symptoms of a vertebral fracture and/or their risk of falling (). The investigation and diagnosis process includes referring patients for BMD measurement performed by dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) to determine the degree of bone loss and, when indicated, to proactively perform vertebral imaging by lateral spine radiographs or vertebral fracture assessment (VFA) to identify any previously undiagnosed fractures. The DXA scan provides a T-score that is derived by comparing a patient’s BMD values (in g/cm2) with BMD values from a uniform Caucasian female normative database; the International Society of Clinical Densitometry recommends the normative database be used for women of all ethnic groups and a Caucasian female reference group be used for men of all ethnic groupsCitation58. The patient’s T-score can be used in fracture risk prediction and diagnosis. Osteoporosis is diagnosed with a BMD T-score ≤−2.5 at any site (lumbar spine, total hip, femoral neck, or distal radius); patients should be given one diagnosis based on the lowest BMD score. Of note, a clinical diagnosis of osteoporosis can also be made in a person with a hip or vertebral fracture, regardless of bone density and in someone with low bone mass (osteopenia; T-score between −1.0 and −2.5) and prior fracture at the humerus, pelvis, or distal radius)Citation4–6 (Supplemental Figure 4 in Supplemental Material).

Figure 3. Patients who warrant BMD testing. aA BMD scan is performed by DXA and provides a T-score (derived by comparing a patient’s BMD values [in g/cm2] with those from a uniform Caucasian female normative database; the International Society of Clinical Densitometry recommends the normative database be used for women of all ethnic groups and a Caucasian female reference group be used for men of all ethnic groups). bLoss of height should ideally be measured with a stadiometer. cDefined as the inability to touch the back of the head to the wall when standing with back and heels against the wall. dTimed up-and-go (TUG) test assesses mobility, balance, walking ability, and fall risk in older adults https://www.cdc.gov/steadi/pdf/TUG_Test-print.pdf [cited 2022 Feb 19]. Briefly, to perform the test, (1) Begin by having the patient sit back in a standard armchair and identify a line 3 m (10 ft) away on the floor and (2) On the word “Go,” record the time it takes for the patient to rise from the chair, walk to the line, and return to the chair, and sit down. An older adult who takes ≥ 12 s to complete the TUG is at risk for falling. BMD, bone mineral density; DXA, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry.

![Figure 3. Patients who warrant BMD testing. aA BMD scan is performed by DXA and provides a T-score (derived by comparing a patient’s BMD values [in g/cm2] with those from a uniform Caucasian female normative database; the International Society of Clinical Densitometry recommends the normative database be used for women of all ethnic groups and a Caucasian female reference group be used for men of all ethnic groups). bLoss of height should ideally be measured with a stadiometer. cDefined as the inability to touch the back of the head to the wall when standing with back and heels against the wall. dTimed up-and-go (TUG) test assesses mobility, balance, walking ability, and fall risk in older adults https://www.cdc.gov/steadi/pdf/TUG_Test-print.pdf [cited 2022 Feb 19]. Briefly, to perform the test, (1) Begin by having the patient sit back in a standard armchair and identify a line 3 m (10 ft) away on the floor and (2) On the word “Go,” record the time it takes for the patient to rise from the chair, walk to the line, and return to the chair, and sit down. An older adult who takes ≥ 12 s to complete the TUG is at risk for falling. BMD, bone mineral density; DXA, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry.](/cms/asset/580d690c-78c9-4dfe-87c0-51085ce23082/icmo_a_2141483_f0003_c.jpg)

Clinical guidelines in some regions recommend BMD testing for postmenopausal women aged 65 years and above and postmenopausal women aged 65 years and below who have risk factorsCitation4–6,Citation59. There is no overall consensus on BMD testing for men, but some guidelines recommend BMD testing for men over 70 years of age as bone loss accelerates at age 70 years and above in menCitation60,Citation61. Guidelines in some regions do not currently recommend BMD testing for all patients; rather, some guidelines recommend BMD measurements using a case-finding strategyCitation62. As best practice, we recommend implementing BMD testing as part of bone health screening per accepted clinical guidelines and as directed by country and local regulations. It may be important to establish a BMD baseline that can be followed over time with or without treatment. This would be analogous to preventive practices such as periodic examinations in adults to screen for diabetes (fasting glucose or hemoglobin A1C)Citation63 and heart disease (cholesterol)Citation64, and mammography for women to screen for breast cancerCitation65.

PCPs should also try to identify patients suspected of having vertebral fractures. This includes routinely asking patients if they have experienced prolonged or unusual back pain, which may signal vertebral fracture (). PCPs should ask patients about signs that might indicate vertebral fractures not previously clinically recognized, such as loss of height by ≥2 cm, the inability to touch the back of the head to the wall when standing with back and heels against the wall (occiput-to-wall distance), or kyphosis (progressive spinal curvature). PCPs should also evaluate for factors that increase the risk of falling such as gait abnormalities, balance problems, and decreased ability to perform the timed “up-and-go” test used to assess balance and gaitCitation4–6 (). Patients with vertebral fractures confirmed by lateral spine radiographs or densitometric VFA or those with bone loss on BMD measurements (T-score ≤ −2.5 or between −1.0 and −2.5 with prior fracture) (Supplemental Figure 4 in Supplemental Material) should proceed to a personalized treatment plan ( and as described in Step 3).

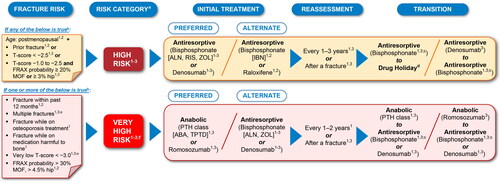

Figure 4. Common elements in fracture risk guidelines and treatment strategies for management of postmenopausal osteoporosis by risk categorization. The recommendations summarized here are a consolidation of recommendations across current clinical guidelines presented in a simplified manner and streamlined for a global audience. Sources: (1) Camacho et al.Citation4; (2) Kanis et al.Citation6 and Kanis et al.Citation43; and (3) Shoback D et al.Citation7 and Eastell et al.Citation68 Routes of administration by drug class: the bisphosphonates ALN, IBN, and RIS are administered as oral tablets; IBN is also available as intravenous injection in several countries; the bisphosphonate ZOL is administered by infusion; denosumab is administered by subcutaneous injection; PTH class of drugs ABA and TPTD are administered by subcutaneous injection; raloxifene is administered as an oral tablet, and romosozumab is administered by subcutaneous injection. Of note, bisphosphonate antiresportive agents (ALN, IBN, RIS, and ZOL) have a different mechanism of action from the other antiresorptive agent denosumab, and it is important that clinicians understand the differential bone effects between these two types of antiresorptive agents. aRegional and local guidelines may override some of these criteria based on differences in FRAX data and cost-effectiveness thresholds. bIf FRAX is not available, major determinants of risk should include age, BMD, fractures, and medication harmful to bone. cOff-treatment period for consideration after treatment with bisphosphonates for 3–5 years due to BMD gains plateauing at ∼3 years. dApplicable if decision is made to discontinue denosumab. eENDO requires both risk factors of multiple fractures and very low T-score < –3.0 to be met for very high risk categorization. fVery high risk category includes the imminent risk subcategory that refers to the relative risk of recurrent fracture that is highest in the first years following an index fracture in patients. ABA, abaloparatide; ALN, alendronate; BMD, bone mineral density; ENDO, Endocrine Society; FRAX, Fracture Risk Assessment Tool; IBN, ibandronate; MOF, major osteoporotic fracture; PTH, parathyroid hormone; RIS, risedronate; TPTD, teriparatide; ZOL, zoledronic acid.

For patients with signs and symptoms that could indicate possible vertebral fracture but no history of fractures and/or a BMD T-score >−2.5, further risk assessment should be performed. Over 80% of postmenopausal women with osteoporotic fractures have a T-score >−2.5Citation66, suggesting that BMD is not the only factor contributing to fracture risk. It has now been established that BMD and other clinical factors taken together improve fracture risk predictionCitation4–6.

Fracture risk prediction can be easily performed using online risk assessment tools such as the Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX), Garvan, American Bone Health (ABH) Fracture Risk Calculator™, and others to help identify patients at increased risk for fracture. These tools appear to perform well and are moderately accurate at predicting fracture risk within a specified time frameCitation43,Citation59. FRAX is the most widely used prediction tool and incorporates risk factors, including age, sex, BMI, fracture history, and othersCitation43 with or without BMD measurement, to predict absolute risk as a 10-year probability of major osteoporotic fracture (fracture of the hip, spine [clinical], wrist, or humerus) and hip fractureCitation2,Citation67 (Supplemental Figure 5 in Supplemental Material). Overall, FRAX and other online tools are meant to guide risk stratification, diagnosis, and treatment decisions; however, clinical judgement is important in determining whether or not to treat patients.

Recent guideline updates, including the 2019 updated IOF/ESCEO guidelineCitation6 also summarized in a 2020 position paperCitation43, the 2020 updated AACE/ACE guidelineCitation4, and the the 2020 Endocrinology Society guidelineCitation7,Citation68, provide criteria for categorizing patients into high risk and very high risk for fracture using FRAX assessment strategies in combination with prior fracture occurrence, age, and T-scores (). Occurrence and recency of a prior fracture are critical in determining patients’ risk for future fracture. In the US, patients are placed into the high risk category for fracture if they are postmenopausal and have experienced a prior fracture, have a T-score ≤−2.5, or have a T-score between −1.0 and −2.5 (osteopenic) together with a FRAX probability of ≥20% for major osteoporotic fracture or ≥3% for hip fractureCitation4,Citation6,Citation7,Citation68. Patients are placed into the very high risk category for fracture if they have experienced a prior fracture within the past 12–24 monthsCitation4,Citation6,Citation7,Citation43,Citation68 due to the high likelihood of a subsequent fracture occurring following a recent fractureCitation15,Citation41–44. Patients are also placed into the very high risk category if they have experienced multiple fractures, had fractures while on osteoporosis medications, have very low T-score (<–3.0), and/or have FRAX probability >30% for major osteoporotic fracture and >4.5% for hip fractureCitation4,Citation6,Citation7,Citation43,Citation68.

Within the very high risk category is the subcategory of patients at imminent risk for fracture, which refers to the relative risk of recurrent fracture that is highest in the first year following an index fracture in patientsCitation7,Citation41,Citation42,Citation44,Citation69.

Other regions and countries may use thresholds for T-score and FRAX probability similar to those used in the US for categorizing patients into high risk and very high risk categories, for example Australia. However, these thresholds may vary in other regions and countries and so it is imperative for PCPs to follow regional and country guidelines.

In cases where fracture risk is determined to be high or very high by the criteria provided in the updated guidelinesCitation4,Citation6,Citation7,Citation43,Citation68 (), patients should be immediately moved to a personalized treatment plan ( and as discussed in Step 3). All other patients, including those at low risk of fracture and/or who have not started treatment with an osteoporosis medication, should be counselled on the use of nonpharmacological measures to preserve bone health (as described in Step 3) and should continue to be monitored through physical examinations, updated history, BMD testing, and FRAX or other risk assessment toolsCitation4–6. For particularly complex cases (e.g. patients with multiple fractures while on treatment or patients with comorbidities and who are on concomitant medications), PCPs may want to refer the patient to a specialist, such as an endocrinologist, rheumatologist, or other clinician with bone-health expertise, or to a PFC program for further patient care.

A sample dialogue with a 60-year-old postmenopausal woman with back pain on a visit to discuss BMD and FRAX results is presented in Supplemental Figure 3 in Supplemental Material, Clinical Scenario 2.

Step 3: intervene

Nonpharmacologic intervention

Nonpharmacologic strategies to preserve bone strength and reduce the risk of fracture, including fall risk assessment and reduction, should be incorporated into routine patient care and assessed at visits for all patients (Supplemental Figure 6 in Supplemental Material). These interventions include counselling patients on maintaining sufficient dietary protein and adequate calcium intake (800–1200 mg/day), preferably from dietary sources with use of calcium supplementation to make up any shortfall, and prescribing vitamin D (800–1000 IU/day or more as indicated) in patients at risk of, or showing evidence of, vitamin D deficiencyCitation6. It also includes recommending regular weight-bearing, muscle‑strengthening, and balance exercises tailored to the needs and abilities of the individual patient, counselling on cessation of smoking and consumption of alcohol in moderation, and guidance on measures to prevent fallsCitation4–6. If warranted, patients can be referred to a dietitian, physiotherapist, or specialist nurse for patient-specific care. It is also important to follow-up with patients on nonpharmacologic intervention, generally 1–2 years after initial osteoporosis screening, to assess for any changes in clinical status or risk factors, and to perform or repeat BMD testing as appropriate. The time frame at which repeat BMD testing is recommended should be individualized based on initial BMD results and clinical risk factors.

Pharmacologic intervention

In patients identified to be at risk for fracture or in those in whom nonpharmacologic intervention is inadequate, personalized treatment plans that incorporate pharmacologic agents should be developed. It is also important to include or continue nonpharmacologic strategies as part of the personalized treatment plan.

Effective therapeutic options for osteoporosis include antiresorptives such as bisphosphonates (alendronateCitation70, ibandronateCitation71, risedronateCitation72, and zoledronic acidCitation73), a RANK ligand inhibitor (denosumab)Citation74, a selective estrogen receptor modulator (raloxifene) Citation75, and menopause hormone therapyCitation6; and anabolic agents such as a parathyroid hormone (PTH) agonist (teriparatideCitation76 and its biosimilars), a PTH receptor agonist (abaloparatide)Citation77, and a sclerostin inhibitor (romosozumab)Citation78 (Supplemental Figure 6 in Supplemental Material). Osteoporosis is a chronic disease, and as such, requires lifetime management, which generally includes pharmacologic treatment and may include a sequence of several medicationsCitation79. The choice of treatment options is a shared decision between the PCP and patient and takes into consideration several factors, including the patient’s baseline level of risk, concomitant medical conditions, and patient preference, and clinical guidelines and local recommendations ()Citation4–7,Citation43,Citation68. If needed, treatment decisions can be made in consultation with a specialist so that patient care on subsequent visits remains aligned among healthcare providers.

For treatment-naïve patients at high risk for fracture, guidelines recommend treatment with an antiresorptive agent as the preferred initial medicationCitation4,Citation6,Citation7,Citation43,Citation68 (). However, for treatment-naïve patients at very high risk for fracture, guidelines recommend an anabolic agent as the preferred initial medicationCitation4,Citation6,Citation7,Citation43,Citation68 (), as treatment with an anabolic followed by antiresorptive therapy is likely to provide greater improvement in bone strength compared with treatment with antiresorptive therapy followed by an anabolic or with antiresorptive therapy aloneCitation80. An ESCEO expert working group concluded that current evidence supports starting patients at very high risk of fracture on an anabolic agent followed by maintenance therapy using an antiresorptive agent and recommend addressing subsequent need for therapy to manage osteoporosis over the lifetime of patientsCitation81

Many patients who are already on antiresorptive therapies may be at very high risk for fracture due to incident fracture, declining BMD, or BMD that remains persistently in the osteoporotic range (T-score ≤–2.5). These patients might also benefit from treatment with anabolic therapy that should be followed with antiresorptive therapy to preserve BMD gains obtained while on an anabolicCitation80. Once patients are placed on the antiresorptive therapy of choice, reassessment is recommended every 1 to 2 yearsCitation4 or after a fractureCitation4,Citation68.

Bisphosphonates and denosumab, although both antiresorptives, have different mechanisms of action and differential bone effects. Treatment with bisphosphonates has been shown to result in BMD gains plateauing at ∼3 yearsCitation70–73; however, the half-life of bisphosphonates in bone is very long (1–10 years) and as such bisphosphonate effect on bone is not readily reversible on drug discontinuation. Thus, a temporary suspension of bisphosphonate therapy (i.e. a drug holiday) after 3–5 years has been recommended in appropriate individuals, as antifracture benefits may continue due to skeletal retention and thus implementing a drug holiday may reduce the risk of potential skeletal adverse eventsCitation4,Citation5. Conversely, the effect of denosumab on BMD gains is reversible, and while continuous BMD gains have been observed with up to 10 years of treatmentCitation82, its discontinuation can result in the loss of bone mass gained while on treatment, with reports of multiple vertebral fractures observed following denosumab discontinuationCitation83–86. As such, discontinuation of denosumab treatment should be followed with an antiresorptive, specifically a bisphosphonate. Treatment with anabolics (teriparatide, abaloparatide, or romosozumab) should also be followed by antiresorptive treatment to maintain BMD gainsCitation5,Citation87,Citation88.

Like most therapeutic treatments, considerations for possible adverse events including risk/benefit should be incorporated in decisions for a treatment plan and discussed with the patient. Safety information for each drug, including side effects, precautions, and boxed warnings, can be found in the prescribing information and have also been extensively reviewed as well as summarized in multiple articlesCitation5,Citation68,Citation89,Citation90.

Some guidelines and expert panels also address treatment goals; i.e., goal-directed therapy, which is a proactive treatment strategy with a clear goal and a commitment to change the therapy if the target is not achieved. The AACE/ACE guideline cites an increase in BMD with no evidence of new fractures or vertebral fracture progression as a response to therapyCitation4; a European expert panel recommends the recovery of prefracture functional level and reduction of subsequent fracture risk as a treatment targetCitation91; and the ASBMR-NOF Working Group on goal-directed treatment for osteoporosis recommends freedom from fracture, a T-score >–2.5, or attaining a lower estimated fracture risk level than at the time of treatment initiationCitation92. Irrespective of the goal selected, it is important to retain the diagnosis of osteoporosis even after the patient achieves improvement, as osteoporosis is a chronic condition like diabetes and hypertension, and requires ongoing treatment and monitoring.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, guidanceCitation93,Citation94 had recommended virtual care, use of alternative methods for administering osteoporosis medications given by subcutaneous injection or intravenous delivery, and temporary transition from injectable to oral medications if necessary until original treatment could be resumed. As a result, various online tools became more widely used for patient care. Incorporation of virtual care and expanded/alternative access measures into routine practice should be considered beyond the COVID-19 pandemic, as this can benefit patients with mobility restrictions or those in rural settings.

A sample dialogue with a 72-year old postmenopausal woman to discuss the results of her annual BMD test is presented in Supplemental Figure 3 in Supplemental Material, Clinical Scenario 3.

Step 4: implement, monitor, and re-evaluate

Monitoring can include ongoing bone-health assessments such as periodic BMD testing and reviewing risk factors as well as interval history of falls and fractures (). Patient adherence is critical in realizing the benefits of osteoporosis therapy, and motivating the patient to continue treatment should be part of ongoing patient-provider discussionsCitation95,Citation96. As many as 30–50% of patients with osteoporosis are nonadherent for a variety of reasonsCitation35,Citation97. Improving adherence to osteoporosis medication requires effective communication with patients about the benefits and risks of treatment, the risks of not treating and consequences of fracture, tailoring treatment options to patient preferences, and close monitoring for early identification of nonadherence. Studies have reported that patients who are persistent with osteoporosis medications have a 30–40% greater decline in fracture rates compared with those who are notCitation98,Citation99. Practices to encourage adherence include simplification of dosing regimens, use of decision aids, changes in route of drug administration, and use of technology to send reminders for refills and/or injection/infusion datesCitation100–102. Additional support can be provided via ongoing patient education, including open discussion about any treatment side-effects, the chronic nature of osteoporosis, patient support programs, patient-centered counselling, and encouraging positive lifestyle changes.

A sample dialogue with a 65-year old postmenopausal woman who was previously diagnosed with osteoporosis (T-score −2.8) and has been on therapy for 1 year is presented in Supplemental Figure 3 in Supplemental Material, Clinical Scenario 4.

Summary

Due to the growing size of the aging population globally, osteoporosis represents an increasing societal and economic burden that warrants the attention of primary care. Osteoporotic fractures are associated with high rates of disability, loss of independence, reduced quality of life for patients and caregivers, and high costs to individuals and healthcare systems. Osteoporosis is currently underdiagnosed and undertreated. As the primary contact with patients, PCPs are uniquely positioned to play a critical role in improving osteoporosis management and closing the treatment gap. We recommend that PCPs adopt a systematic approach of proactively screening patients to identify those at risk for osteoporosis and implement individualized treatment plans and follow-up to reduce the likelihood of debilitating osteoporotic fractures. This requires PCPs to gain knowledge of osteoporosis risk factors and understand the role of BMD testing and application of risk assessment tools to best treat and serve their patients. PCPs may also need to work as part of multidisciplinary teams with other medical specialties, including working groups, to offer outreach, case finding, treatment, referral, and health education. The simple strategy presented in this article can be used to guide PCPs in making decisions regarding the course of action when managing patients at risk for osteoporosis and osteoporotic fracture within the primary care setting.

Transparency

Author contributions

The authors meet the criteria for authorship as recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE). All authors take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, from inception to published article. All authors contributed to the study concept, analysis of data, interpretation of the results, drafting and editing of the manuscript, and approved submission of the manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (5.3 MB)Acknowledgements

Medical writing assistance was provided by Martha Mutomba, PhD (on behalf of Amgen Inc.) and Lisa Humphries, PhD of Amgen Inc.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

Andrea J. Singer has received research/grant support from Radius and UCB Pharma, paid to Georgetown University and MedStar; consulting/advisory board fees from AgNovos, Amgen, Radius, and UCB Pharma; speaker’s bureau fees from Amgen and Radius, and has also served on the National Osteoporosis Foundation Board of Trustees (non-remunerative). Anita Sharma has received honorarium from Amgen. Cynthia Deignan is an employee and stockholder of Amgen. Liesbeth Borgermans has received research/grant support from Amgen. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Data availability statement

Qualified researchers may request data from Amgen clinical studies. Complete details are available at the following: https://wwwext.amgen.com/science/clinical-trials/clinical-data-transparency-practices/clinical-trial-data-sharing-request/.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Jakab M, Farrington J, Borgermans L, et al. Health systems respond to noncommunicable diseases: time for ambition. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe; 2018 [cited 2022 Jul 22]. https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/9789289053402

- International Osteoporosis Foundation. Facts and statistics. Epidemiology of osteoporosis and fragility fractures. [cited 2022 July 22]. https://www.osteoporosis.foundation/facts-statistics/epidemiology-of-osteoporosis-and-fragility-fractures

- NIH Consensus Development Panel on Osteoporosis Prevention, Diagnosis, and Therapy. Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. JAMA. 2001;285(6):785–795.

- Camacho PM, Petak SM, Binkley N, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis—2020 update. Endocr Pract. 2020;26(Suppl 1):1–46.

- LeBoff MS, Greenspan SL, Insogna KL, et al. The clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2022;33(10):2049–2102.

- Kanis JA, Cooper C, Rizzoli R, et al. European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2019;30(1):3–44.

- Shoback D, Rosen CJ, Black DM, et al. Pharmacological management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: an Endocrine Society guideline update. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105(3):dgaa048.

- Management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: the 2021 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2021. 28(9):973–997.

- International Osteoporosis Foundation and Bone Health & Osteoporosis Foundation. Osteoporosis and fracture risk evaluation. A tool for primary care providers (US version). [cited 2022 Jul 22]. http://www.bonehealthandosteoporosis.org/wp-content/uploads/Radically-Simple-Tool_BHOF.pdf

- International Osteoporosis Foundation and Bone Health & Osteoporosis Foundation. Osteoporosis and fracture risk evaluation. A tool for primary care physicians to share with patients (UK version). [cited 2022 Jul 22]. https://www.osteoporosis.foundation/sites/iofbonehealth/files/2022-06/RadicallySimpleTest_IOF_EN_0.pdf

- Johnell O, Kanis JA. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17(12):1726–1733.

- GBD 2019 Fracture Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of bone fractures in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021;2:e580–e592.

- Shepstone L, Lenaghan E, Cooper C, et al. Screening in the community to reduce fractures in older women (SCOOP): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10122):741–747.

- Bone Health and Osteoporosis Foundation. National Bone Health Policy Institute. Facts about bone health. [cited 2022 Jul 22]. https://www.bonehealthpolicyinstitute.org/bone-facts

- Hansen D, Pelizzari P, Pyenson B. Medicare cost of osteoporotic fractures - 2021 updated report: the clinical and cost burden of fractures associated with osteoporosis. March 2021. Commissioned by the National Osteoporosis Foundation. [cited 2022 Jul 22]. https://www.milliman.com/en/insight/-/media/milliman/pdfs/2021-articles/3-30-21-Medicare-Cost-Osteoporotic-Fractures.ashx

- Tajeu GS, Delzell E, Smith W, et al. Death, debility, and destitution following hip fracture. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69(3):346–353.

- Tarride J-E, Hopkins RB, Leslie WD, et al. The burden of illness of osteoporosis in Canada. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23(11):2591–2600.

- Xie Z, Burge R, Yang Y, et al. Posthospital discharge medical care costs and family burden associated with osteoporotic fracture patients in China from 2011 to 2013. J Osteoporos. 2015;2015:258089.

- National Osteoporosis Society. Life with osteoporosis: the untold story. [cited 2022 Jul 22]. https://alterlinehealth.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/NOS-Life-with-Osteoporosis-the-untold-story-Alterline.pdf

- Singer A, Exuzides A, Spangler L, et al. Burden of illness for osteoporotic fractures compared with other serious diseases among postmenopausal women in the United States. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(1):53–62.

- Sernbo I, Johnell O. Consequences of a hip fracture: a prospective study over 1 year. Osteoporos Int. 1993;3(3):148–153.

- Lewiecki EM, Ortendahl JD, Vanderpuye-Orgle J, et al. Healthcare policy changes in osteoporosis can improve outcomes and reduce costs in the United States. JBMR Plus. 2019;3(9):e10192.

- Borgström F, Karlsson L, Ortsäter G, et al. Fragility fractures in Europe: burden, management and opportunities. Arch Osteoporos. 2020;15(1):59.

- Kanis JA, Norton N, Harvey NC, et al. SCOPE 2021: a new scorecard for osteoporosis in Europe. Arch Osteoporos. 2021;16(1):82.

- International Osteoporosis Foundation. IOF compendium of osteoporosis. [cited 2022 Jul 22]. http://share.iofbonehealth.org/WOD/Compendium/2019-IOF-Compendium-of-Osteoporosis-PRESS.pdf

- Willers C, Norton N, Harvey NC, et al. Osteoporosis in Europe: a compendium of country-specific reports. Arch Osteoporos. 2022;17(1):23.

- International Osteoporosis Foundation. Capture the fracture. [cited 2022 Jul 22]. https://www.capturethefracture.org/faq

- Gullberg B, Johnell O, Kanis JA. World-wide projections for hip fracture. Osteoporos Int. 1997;7(5):407–413.

- Nguyen TV, Center JR, Eisman JA. Osteoporosis: underrated, underdiagnosed and undertreated. Med J Aust. 2004;180(S5):S18–S22.

- Yusuf AA, Matlon TJ, Grauer A, et al. Utilization of osteoporosis medication after a fragility fracture among elderly medicare beneficiaries. Arch Osteoporos. 2016;11(1):31.

- Boudreau DM, Yu O, Balasubramanian A, et al. A survey of women’s awareness of and reasons for lack of postfracture osteoporotic care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(8):1829–1835.

- Sale JEM, Beaton D, Posen J, et al. Systematic review on interventions to improve osteoporosis investigation and treatment in fragility fracture patients. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22(7):2067–2082.

- Solomon DH, Johnston SS, Boytsov NN, et al. Osteoporosis medication use after hip fracture in U.S. patients between 2002 and 2011. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29(9):1929–1937.

- Rabenda V, Reginster J-Y. Overcoming problems with adherence to osteoporosis medication. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2010;10(6):677–689.

- Kothawala P, Badamgarav E, Ryu S, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of real-world adherence to drug therapy for osteoporosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82(12):1493–1501.

- Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, et al. European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(1):23–57.

- Willson T, Nelson SD, Newbold J, et al. The clinical epidemiology of male osteoporosis: a review of the recent literature. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:65–76.

- Weaver CM, Gordon CM, Janz KF, et al. The National Osteoporosis Foundation’s position statement on peak bone mass development and lifestyle factors: a systematic review and implementation recommendations. Osteoporos Int. 2016;27(4):1281–1386.

- Cauley JA, Cawthon PM, Peters KE, et al. Risk factors for hip fracture in older men: the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study (MrOS). J Bone Miner Res. 2016;31(10):1810–1819.

- Center JR, Bliuc D, Nguyen TV, et al. Risk of subsequent fracture after low-trauma fracture in men and women. JAMA. 2007;297(4):387–394.

- Balasubramanian A, Zhang J, Chen L, et al. Risk of subsequent fracture after prior fracture among older women. Osteoporos Int. 2019;30(1):79–92.

- Johansson H, Siggeirsdóttir K, Harvey NC, et al. Imminent risk of fracture after fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28(3):775–780.

- Kanis JA, Harvey NC, McCloskey E, et al. Algorithm for the management of patients at low, high and very high risk of osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2020;31(1):1–12.

- van Geel TACM, van Helden S, Geusens PP, et al. Clinical subsequent fractures cluster in time after first fractures. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(1):99–102.

- Conley RB, Adib G, Adler RA, et al. Secondary fracture prevention: consensus clinical recommendations from a multistakeholder coalition. J Bone Miner Res. 2020;35(1):36–52.

- Weaver J, Sajjan S, Lewiecki EM, et al. Prevalence and cost of subsequent fractures among U.S. patients with an incident fracture. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(4):461–471.

- Gillespie CW, Morin PE. Trends and disparities in osteoporosis screening among women in the United States, 2008–2014. Am J Med. 2017;130(3):306–316.

- Ganda K, Mitchell PJ, Seibel MJ. Chapter 3 - models of secondary fracture prevention: systematic review and metaanalysis of outcomes. In: Seibel MJ, Mitchell PJ, editors. Secondary fracture prevention: an international perspective. London: Academic Press; 2019. p. 33–62.

- Grigoryan KV, Javedan H, Rudolph JL. Orthogeriatric care models and outcomes in hip fracture patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28(3):e49–e55.

- International Osteoporosis Foundation. Capture the fracture map of best practice. [cited 2022 Jul 22]. http://capturethefracture.org/map-of-best-practice

- Greenspan SL, Singer A, Vujevich K, et al. Implementing a fracture liaison service open model of care utilizing a cloud-based tool. Osteoporos Int. 2018;29(4):953–960.

- Ganda K, Puech M, Chen JS, et al. Models of care for the secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(2):393–406.

- Li N, van Oostwaard M, van den Bergh JP, et al. Health-related quality of life of patients with a recent fracture attending a fracture liaison service: a 3-year follow-up study. Osteoporos Int. 2022;33(3):577–588.

- Black DM, Arden NK, Palermo L, et al. Prevalent vertebral deformities predict hip fractures and new vertebral deformities but not wrist fractures. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14(5):821–828.

- Gehlbach S, Saag KG, Adachi JD, et al. Previous fractures at multiple sites increase the risk for subsequent fractures: the global longitudinal study of osteoporosis in women. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27(3):645–653.

- Colón-Emeric C, Kuchibhatla M, Pieper C, et al. The contribution of hip fracture to risk of subsequent fractures: data from two longitudinal studies. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14(11):879–883.

- Johnell O, Kanis JA, Odén A, et al. Fracture risk following an osteoporotic fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15(3):175–179.

- International Society for Clinical Densitometry. 2019. ISCD official positions: adult. [cited 2022 Jul 22]. https://iscd.org/learn/official-positions/adult-positions/

- Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al. Screening for osteoporosis to prevent fractures: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;319(24):2521–2531.

- Ebeling PR. Clinical practice. Osteoporosis in men. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(14):1474–1482.

- Szulc P, Delmas PD. Biochemical markers of bone turnover in men. Calcif Tissue Int. 2001;69(4):229–234.

- National Osteoporosis Guideline Group. NOGG 2021: Clinical guideline for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. [cited 2022 Jul 22]. https://www.nogg.org.uk/full-guideline

- American Diabetes Association. 6. Glycemic targets: standards of medical care in diabetes–2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(Suppl 1):S66–S76. [cited 2022 Jul 22]. https://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/43/Supplement_1/S66

- Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: executive summary: a report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2019;140(11):e563–e595.

- Qaseem A, Lin JS, Mustafa RA, et al. Screening for breast cancer in average-risk women: a guidance statement from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(8):547–560.

- Siris ES, Chen Y-T, Abbott TA, et al. Bone mineral density thresholds for pharmacological intervention to prevent fractures. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(10):1108–1112.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology (NCCN Guidelines) for non-small cell lung cancer V1.2022. [cited 2022 June 13]. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nscl.pdf

- Eastell R, Rosen CJ, Black DM, et al. Pharmacological management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(5):1595–1622.

- Roux C, Briot K. Imminent fracture risk. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28(6):1765–1769.

- Fosamax (alendronate sodium) prescribing information, Merck & Co. 1995. [cited 22 Jul 2022]. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/020560s068,021575s024lbl.pdf

- Boniva (ibandronate sodium) prescribing information, Genentech 2003. [cited 22 Jul 2022]. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/021455s009lbl.pdf

- Actonel (risedronate sodium) prescribing information, Allergan 1998. [cited 22 Jul 2022]. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2009/020835s035lbl.pdf

- Reclast (zoledronic acid) prescribing information, Novartis 2001. [cited 22 Jul 2022]. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/021817s027lbl.pdf

- Prolia (denosumab) prescribing information, Amgen Inc. 2010. [cited 22 Jul 2022]. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/125320s0000lbl.pdf

- Evista (raloxifene hydrochloride) prescribing information, Eli Lilly & Company 1997. [cited 22 Jul 2022]. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2007/022042lbl.pdf

- Forteo (teriparatide) prescribing information, Eli Lilly & Company 1987. [cited 22 Jul 2022]. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/021318s053lbl.pdf

- Tymlos (abaloparatide) prescribing information, Radius Health 2017. [cited 22 Jul 2022]. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/208743lbl.pdf

- Evenity (romosozumab-aqqg) prescribing information, Amgen Inc. 2019. [cited 22 Jul 2022]. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/761062s000lbl.pdf

- Cosman F, Nieves JW, Dempster DW. Treatment sequence matters: anabolic and antiresorptive therapy for osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2017;32(2):198–202.

- Cosman F. Anabolic therapy and optimal treatment sequences for patients with osteoporosis at high risk for fracture. Endocr Pract. 2020;26(7):777–786.

- Curtis EM, Reginster JY, Al-Daghri N, et al. Management of patients at very high risk of osteoporotic fractures through sequential treatments. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2022;34(4):695–714.

- Bone HG, Wagman RB, Brandi ML, et al. 10 Years of denosumab treatment in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: results from the phase 3 randomised FREEDOM trial and open-label extension. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5(7):513–523.

- Brown JP, Roux C, Törring O, et al. Discontinuation of denosumab and associated fracture incidence: analysis from the fracture reduction evaluation of denosumab in osteoporosis every 6 months (FREEDOM) trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28(4):746–752.

- Cummings SR, Ferrari S, Eastell R, et al. Vertebral fractures after discontinuation of denosumab: a post hoc analysis of the randomized placebo-controlled FREEDOM trial and its extension. J Bone Miner Res. 2018;33(2):190–198.

- McClung MR, Wagman RB, Miller PD, et al. Observations following discontinuation of long-term denosumab therapy. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28(5):1723–1732.

- Lamy O, Gonzalez-Rodriguez E, Stoll D, et al. Severe rebound-associated vertebral fractures after denosumab discontinuation: 9 clinical cases report. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(2):354–358.

- Cosman F, Crittenden DB, Adachi JD, et al. Romosozumab treatment in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(16):1532–1543.

- Saag KG, Petersen J, Brandi ML, et al. Romosozumab or alendronate for fracture prevention in women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(15):1417–1427.

- Gregson CL, Armstrong DJ, Bowden J, et al. UK clinical guideline for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Arch Osteoporos. 2022;17(1):58.

- McClung MR, Rothman MS, Lewiecki EM, et al. The role of osteoanabolic agents in the management of patients with osteoporosis. Postgrad Med. 2022;134(6):541–551.

- Thomas T, Casado E, Geusens P, et al. Is a treat-to-target strategy in osteoporosis applicable in clinical practice? Consensus among a panel of european experts. Osteoporos Int. 2020;31(12):2303–2311.

- Cummings SR, Cosman F, Lewiecki EM, et al. Goal-directed treatment for osteoporosis: a progress report from the ASBMR-NOF working group on goal-directed treatment for osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2017;32(1):3–10.

- Joint guidance on osteoporosis management in the era of COVID-19 from the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research (ASBMR), American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE), Endocrine Society, European Calcified Tissue Society (ECTS) and National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF) [published 2020 May 7; cited 2022 Jul 22]. https://www.endocrine.org/-/media/endocrine/files/membership/joint-statement-on-covid19-and-osteoporosis-final.pdf

- Joint guidance on COVID-19 vaccination and osteoporosis management from the ASBMR, AACE, ECTS, IOF, and NOF [published 2021 Mar 9; cited 2022 Jul 22]. https://www.asbmr.org/about/statement-detail/joint-guidance-on-covid-19-vaccine-osteoporosis

- Barrionuevo P, Kapoor E, Asi N, et al. Efficacy of pharmacological therapies for the prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women: a network meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(5):1623–1630.

- Chesnut CH, IIISkag A, Christiansen C, et al. Effects of oral ibandronate administered daily or intermittently on fracture risk in postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19(8):1241–1249.

- Hall SF, Edmonds SW, Lou Y, et al. Patient-reported reasons for nonadherence to recommended osteoporosis pharmacotherapy. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2017;57(4):503–509.

- Liu J, Guo H, Rai P, et al. Medication persistence and risk of fracture among female medicare beneficiaries diagnosed with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2018;29(11):2409–2417.

- Sunyecz JA, Mucha L, Baser O, et al. Impact of compliance and persistence with bisphosphonate therapy on health care costs and utilization. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19(10):1421–1429.

- Gleeson T, Iversen MD, Avorn J, et al. Interventions to improve adherence and persistence with osteoporosis medications: a systematic literature review. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20(12):2127–2134.

- Hiligsmann M, Salas M, Hughes DA, et al. Interventions to improve osteoporosis medication adherence and persistence: a systematic review and literature appraisal by the ISPOR medication adherence & persistence special interest group. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(12):2907–2918.

- Lee S, Glendenning P, Inderjeeth CA. Efficacy, side effects and route of administration are more important than frequency of dosing of anti-osteoporosis treatments in determining patient adherence: a critical review of published articles from 1970 to 2009. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22(3):741–753.