Abstract

Objectives

The term “mixed pain” has been established when a mixture of different pain components (e.g. nociceptive, neuropathic, and nociplastic) are present. It has gained more and more acceptance amongst pain experts worldwide, but many questions around the concept of mixed pain are still unsolved. The sensation of pain is very personal. Cultural, social, personal experiences, idiomatic, and taxonomic differences should be taken into account during pain assessment. Therefore, a Latin American consensus committee was formed to further elaborate the essentials of mixed pain, focusing on the specific characteristics of the Latin American population.

Methods

The current approach was based on a systematic literature search and review carried out in Medline. Eight topics about the definition, diagnosis, and treatment of mixed pain were discussed and voted for by a Latin American consensus committee and recommendations were expressed.

Results

At the end of the meeting a total of 14 voting sheets were collected. The full consensus was obtained for 21 of 25 recommendations (15 strong agreement and 6 unanimous agreement) formulated for the above described 8 topics (7 of the 8 topics had for all questions at least a strong agreement − 1 topic had no agreement for all 4 questions).

Conclusion

In a subject as complex as mixed pain, a consensus has been reached among Latin American specialists on points related to the definition and essence of this pain, its diagnosis and treatment. Recommendations for diagnosis and treatment of mixed pain in Latin America were raised.

Introduction

The concept of pain is of such importance that already in the 1990s Dr. James Campbell proposed the American Pain Society to include it in the canons of medicine as a “fifth vital sign”Citation1. Even before that, Dr. Mitchell Max pointed out that for two decades no progress in the assessment and management of pain had been madeCitation2. Thirty years later, research on the definitions, pathophysiology, diagnosis, classification, and treatment of pain are still ongoing and international organizations like the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO), the World Health Organization (WHO), among others, have not reached a consensus on the topic. The reason is simple: each patient perceives pain differently, it is a subjective symptom, so the use of tools to address and quantify it is very complex due to its high variabilityCitation3.

Whenever a mixture of different pain components (e.g. nociceptive, neuropathic, and nociplastic) are present, the term “mixed pain” was establishedCitation4. In recent years this concept has been recognized and was accepted by different authors from around the worldCitation5–13.

In March 2019 a committee of international pain specialists came together in order to clarify the concept of “mixed pain”. This meeting was led by Dr. Rainer Freynhagen, a specialist in anesthesiology, intensive care, pain management, palliative care, and sports medicine. Based on the review of the scientific literature from 1990 to 2018, a definition emerged: “Mixed pain is a complex overlap of the different known pain types (nociceptive, neuropathic, nociplastic) in any combination, acting simultaneously and/or concurrently to cause pain in the same body area. Either mechanism may be more clinically predominant at any point of time. Mixed pain can be acute or chronic”Citation14. This concept has still not been accepted by the IASP either.

Due to many unanswered questions around the concept of mixed pain, a Latin American consensus committee was formed. The objective of the consensus was to further get Latin American specialists to respond and agree on some essential points regarding mixed pain from the perspective of linguistic, cultural, and social peculiarities of the Latin American population in terms of definition, taxonomy, diagnosis, and treatment. It is the continuation of the informal discussions held at the meeting led by Dr. Freynhagen in Cancun in 2019, which brought to light the differences on these points between the Latin American participants and those from other countries in the world. The outcomes of this Latin American consensus process and the final 2 d face-to-face meeting are presented herein.

Materials and Methods

Selection of consensus committee members

During the forementioned international meeting initiated by Dr. Rainer Freynhagen in March 2019, four participants with a Spanish-speaking background decided to carry out a similar meeting, taking linguistic and cultural features of Latin America into account. Sixteen well-established pain experts, natives from different Latin American countries, and various specializations (algology, anesthesia, physiotherapy, internal medicine, family medicine, diabetology, orthopedic surgery, pharmacology, and neurosciences) were nominated to form a multidisciplinary consensus group. The majority of the nominees are orthopedic specialists since many painful conditions suffered in the pathology of the musculoskeletal system are of a mixed natureCitation10. All nominees are dealing with mixed pain on a regular basis, both, during their work as clinicians and in research and they were chosen randomly based on professional contacts.

Selection of the topics to being addressed

The four initiators of the consensus committee (CCO, CPH, FFV, MFF) defined the main topics to being addressed based on their experience and broad knowledge in the field of mixed pain. This resulted in eight topics including the definition, diagnosis, and treatment of mixed pain. Sub-topics were drafted as guidance and to guarantee that the most noteworthy and so-far unresolved issues will be included. All topics could be adapted, and sub-topics could be changed, added, or deleted, as needed when deemed necessary by the consensus committee at any stage of the process. The initial topics and sub-topics that were chosen for elaboration and discussion are presented in .

Table 1. Initially planned topics for the consensus meeting.

Each of the eight topics was assigned to two of the nominated experts, based on his/her individual profile and area of expertise. The purpose was to obtain a reliable consensus of opinion from a multidisciplinary group of experts.

Systematic literature search and review

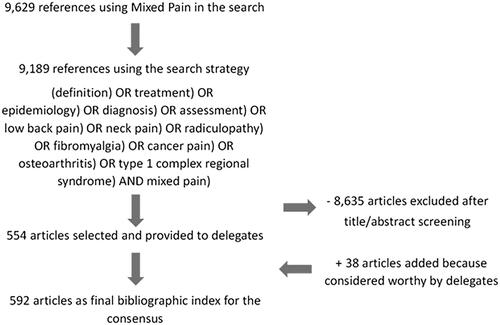

A systematic literature search was carried out by scanning Medline for the Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) “Mixed Pain” via PubMed yielding 9629 articles. The search strategy encompassed articles from any prior date up to August 2019, including pre-prints. There were no limitations in terms of the type and quality of studies, language, or provenance. Articles in other languages were translatable by at least one of the consensus committee members. Subsequently, the search strategy was limited as follows: (((((((((((((definition) OR treatment) OR epidemiology) OR diagnosis) OR assessment) OR low back pain) OR neck pain) OR radiculopathy) OR fibromyalgia) OR cancer pain) OR osteoarthritis) OR type 1 complex regional syndrome) AND mixed pain), yielding 9189 references. Since a random comparison between both searches showed, that all-important references were also included in the second one, those were used as the baseline bibliography.

The title and abstract of each of the 9189 identified references were screened for their relevance to the current approach by two independent reviewers (APT and EA). The articles directly related to Mixed Pain that were considered relevant were selected and reviewed.

The interobserver agreement was κ = 0.87. Discrepancies were settled by the consensus coordinator. A total of 554 articles were selected that way and the respective full texts were provided to the 16 nominated members of the consensus committee. They were instructed to skim those articles and each consensus member selected the ones that could help to elaborate the topic assigned to him/her. The levels of scientific evidence and grades of recommendation were to be assessed for each chosen article according to the SIGN scale when possibleCitation15. The quality of the methodology and risk of bias were not assessed.

Secondary literature of interest, that was referenced in the original bibliography could be added if considered worthy by the consensus members. Furthermore, each consensus member could throughout the consensus process add additional references he/she was aware of because of his/her expertise. This step was merely based on personal considerations. Most of the supplementary provided bibliography did not specifically refer to mixed pain, despite providing useful complementary data; that is why it was not found in the original search. This way 38 articles were appended (). Those articles were also evaluated by the two independent reviewers (APT and EA) mentioned above, to judge the quality, in accordance with the purpose of the consensus.

Consensus workflow and methods to achieve consensus

The process to achieve consensus ran from April 2019 to February 2020 and consisted of the following major three phases: (1) consensus committee members worked remotely on their assigned topics and exchanged ideas via an online platform; (2) participants worked face-to-face to address final issues, determined final recommendations for each topic and voted for them; and (3) drafting and publication of this article. Each of those phases is further detailed in the following paragraphs.

Elaboration of each topic via an online platform

The two assigned consensus members were to work individually and/or collaboratively on their topic, using the provided (supplemented) bibliography. The opinion of both delegates was obtained in all the points analyzed. The first elaboration of each section was presented to the totality of the consensus committee via an online platform on December 31, 2019. This initial proceeding followed a modified Delphi method similar to the one applied during the International Consensus on Periprosthetic Joint Infection, held in Philadelphia in 2013Citation16, and the methodology followed during the Italian Consensus Conference on Pain in Neurorehabilitation published in 2016Citation17.

Each participant was encouraged to express his/her opinion on each topic, avoiding the inactivity and/or silence of members. All comments and suggestions that came up during that online meeting were carefully evaluated, taken into account during the following proceedings and implemented into the document.

One major criticism of this process is that three members of the steering committee later actively participated in the discussions and voting, but this was also the case in the consensus that served as a model. There was thus a certain endogeneity in the process counteracted in some way by giving equal opportunity to all delegates to voice their views with equal weight, and efforts were made to mitigate the potential effect of differential status of participants. Comments were depersonalized and voting was anonymous.

2-day face-to-face meeting including final voting

The final plenary was a 2-day face-to-face meeting of the consensus committee members taking place on February 7 and 8, 2020 in Mexico City, Mexico. It had the characteristics of a consensus conference, with no time limit, trying to avoid redundant topics and dominant influences of any kind. The meeting and discussions were therefore coordinated and moderated by a neutral person (MFF), who was not taking part in the voting. On Day 1 a presentation on each of the eight topics was given by the (two) assigned expert(s). It summarized general findings from the assessment of the provided and adapted literature, discussions that had been taken place on the online platform proceeding this meeting as a modified Delphi process, and thoughts of the experts including suggestions on how to resolve any discrepancies that had come up.

Discussions on each topic were encouraged and carried out without any time limits. At the end of Day 1 the whole group of delegates voted if each of the discussed topics is generally relevant and could give their considerations and proposals for each question on anonymous voting sheets. Day 2 started with further discussions based on the considerations and proposals to each topic from all delegates which were summarized by the coordinator and host (MFF). Thereafter, recommendations for each topic were agreed on/elaborated together. This included the creation of new/different sub-topics for some of the topics.

All discussions held and documents generated were in Spanish.

At the end of the meeting, each delegate voted if he/she agreed with those recommendations. The assessment of the general relevance of each topic (voted for on Day 1), and each committee member’s agreement to the final recommendations presented below (see Materials and Methods) was made using a scale from 1 to 5 consisting of the following individual grades: 1 = total disagreement, 2 = partial disagreement, 3 = neutral, 4 = partial agreement, 5 = total agreement. Evaluation of the votes followed again the approach carried out by Cats-Baril and colleaguesCitation16: an agreement of less than 60% of the votes was considered as no consensus, a supermajority between 60% and 74% was considered a weak consensus, a supermajority equal or greater than 75% as a strong consensus, and 100% as unanimousCitation16. This means that in our approach a consensus was reached when at least 60% of the voting delegates voted for 4 or 5. In addition to the above criteria, a binomial statistical test was provided to assess if the probability agreeing (voted 4–5) differs (p < .05) from neutral to disagreement (voted 1–3) for questions of interest.

Drafting and publication of the article

A draft version in Spanish of this article was submitted to all members of the consensus. They could provide comments on the manuscript and then it was translated into English for publication.

Results and discussion

Each of the eight topics had been assigned to and worked on by two experts, but two of the consensus meeting members could not take part in the face-to-face meeting and final voting due to personal reasons. The 8 topics that had been pre-selected for further elaboration during the 2 d face-to-face consensus meeting were all deemed being relevant by the 14 committee members. At the end of the meeting, a total of 14 voting sheets were collected. The full consensus was obtained for 21 of 25 recommendations (15 strong agreement and 6 unanimous agreement) formulated for the above described 8 topics (7 of the 8 topics had for all questions at least a strong agreement − 1 topic had no agreement for all 4 questions). Further details for each topic and recommendation, as well as the major outcomes of discussions of the meeting are given in the following chapters.

What is mixed pain?

As already stated, the currently only available attempt to define mixed pain was made by Freynhagen and colleagues following an international consensus meeting in 2018 and reads as follows: “Mixed pain is a complex overlap of the different known pain types (nociceptive, neuropathic, nociplastic) in any combination, acting simultaneously and/or concurrently to cause pain in the same body area. Either mechanism may be more clinically predominant at any point of time. Mixed pain can be acute or chronic”Citation14.

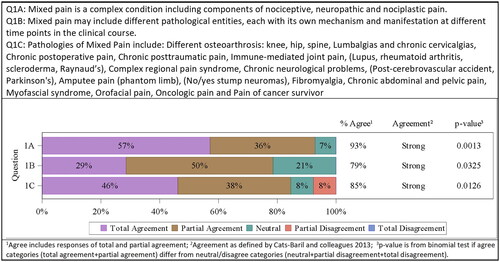

The majority of the members of the Latin American consensus meeting acknowledged the accuracy of this definition by Freynhagen et al. but asserted that its translation into the Spanish language harbors certain dangers. Misunderstandings and confusions due to different regional, cultural, and social aspects can occur. It was therefore agreed to suggest a shorter and simpler definition to being used in Spanish-speaking countries: “Dolor mixto es una condición compleja en la que se suman componentes de dolor nociceptivo, neuropático y nociplástico”, which translates “Mixed pain is a complex condition including components of nociceptive, neuropathic and nociplastic pain”. The alternative definition was accepted by the majority of the consensus committee (8/14 totally agreed, 5/14 partially agreed, 1/14 neutral, 0/14 disagreed). Strong agreement was confirmed by the committee 13/14 (93%; p = .0013). All additional details, which were part of Freynhagen’s definition, are covered in the following paragraphs.

So far, the term “mixed pain” has not been included in the current IASP definitions and its pathophysiology is still undefined. The differences between mixed and combined pain were discussed. It was emphasized that the latter is the coexistence of two pain generators in the same area, while mixed pain describes the existence of simultaneous pains related to the same triggering etiologyCitation14. The consensus committee agreed that mixed pain may include different pathological entities, each with its own mechanism and manifestation at different time points in the clinical course (4/14 totally agreed, 7/14 partially agreed, 3/14 neutral, 0/14 disagreed). Strong agreement was confirmed by the committee 11/14 (79%; p = .0325).

The nociplastic component is not necessarily present in all mixed pain scenarios. Due to the possibility of altered nociception in chronic pain, the nociplastic component may be more prevalent in those cases, but not in acute cases. It is not clear whether it is possible to have a combination of nociceptive and nociplastic pain. Central sensitization, disinhibition, and facilitation characterize the transformation from nociceptive to nociplastic pain. Central sensitization and changes in brain activation and connectivity are the main underlying mechanism of nociplastic pain, with manifestations of central sensitization generally present in nociplastic painCitation5. Some delegates judged that the term “dysfunctional” is better than “nociplastic” but after discussing this point it was agreed to continue using nociplastic as it is currently preferred over dysfunctional.

A list of pathologies that can promote mixed pain was proposed by the plenary, including conditions producing chronic pain with a neuropathic component, collected from the work of Ibor et al.Citation10, the International Classification of Diseases-11 (ICD-11) chronic pain classification, and the IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: chronic neuropathic pain, and presented in (6/13 totally agreed, 5/13 partially agreed, 1/13 neutral, 1/13 partially disagreed). Strong agreement was confirmed by the committee 11/13 (85%; p = .0126) (). Probably the future requires to integrate in it more painful entities as their mechanisms of pain are known more deeply and with greater precision.

Table 2. Pathologies where mixed pain can be expressed.

Diagnosis of mixed pain

The literature was assessed to gather information about the diagnosis of mixed pain. Generally, pain anamnesis should be thorough and include questions about the patient’s medical history, as well as his/her psychosocial background. Moreover, the patient should be allowed to fully describe his/her pain experience and the physician should listen carefully. Questioning about pain should include assessment of its location, intensity, character, time profile (acute or chronic), triggering, mitigating, and exacerbating factors, accompanying symptoms, their impact on mobility, activities of daily living, relationship to their social environment, and interference with sleep and mood. If possible and deemed necessary, a multidisciplinary team should be involved and the whole process should be individualized on the patient’s needs. It is of utmost importance to take regional, social, and individual factors into account during the anamnesis.

The nine questions proposed by Freynhagen et al.Citation12, could be a good starting point to develop a useful tool to address/diagnose clinical conditions of mixed pain. The anatomical distribution of pain is a key question as it provides the clinician with a framework for identifying the predominant pain mechanisms operating within the patient. The distribution of pain following a defined neuroanatomical pattern or not is essential to diagnose it as pure neuropathic pain or associated with a nociceptive and/or nociplastic component. And the same can be said regarding its extension through a clear dermatomal pattern or its generalization. Carefully conducted, a patient-centered interview must be a collaborative effort between physician and patient based on the patient’s individual cognitive and communication style asking the right questions to identify the predominant pain mechanisms operating within the individual patient.

Questionnaires are a powerful tool during pain diagnostic, but no literature analyzing the application of a self-administered questionnaire (approved screening tool) for mixed pain was identified. Although there are multiple validated and reliable tools, none provides a complete assessment for all situations in which pain occurs, including idiomatic and cultural interpretations of painCitation18–20. One should keep in mind that any questionnaire is only an attempt to help diagnosing and can never replace a thorough physical examination. Several of those questionnaires were briefly presented, like the Short Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ), Chronic Pain Grade Score (CPGS), Short Form 36 Body Pain Score (SF-36 BPS), and painDETECT questionnaire, the “Douleur Neuropathique 4” (DN4) questionnaire, the Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs (LANSS), and the Central Sensitization Inventory (CSI), all having their adapted version for the use in Spanish-speaking countriesCitation21–28. All those questionnaires have their strengths and weaknesses. They were discussed by the consensus members. It is necessary to select the most appropriate one for each specific purpose, continue to work on its development and subsequent validation.

The questionnaire by McGill (SF-MPQ) is a classic, generic, widely known, and used questionnaire, which allows the patient to describe pain via many terms and through them introducing descriptors. It allows the physician to easily categorize pain, showing a high internal validity and similar ordinal consistency, inter-category, inter-parameter, and qualitative-to-quantitative parameter correlations when used to evaluate Spanish-speaking patients from different Latin American countriesCitation22. None of the other questionnaires mentioned have been analyzed and validated in this manner.

Based on all these initially emphasized proceedings during anamnesis which were discussed and agreed on by the committee, the following recommendations for the diagnosis of mixed pain were phrased and voted for:

Whenever a patient presents with neuropathic pain, rule out the possibility of mixed pain (11/14 totally agreed, 3/14 partially agreed). Unanimous agreement was confirmed by the committee 14/14 (100%; p = .0002).

Routine use of the questionnaire by McGill as an approximation for mixed pain (5/14 totally agreed, 6/14 partially agreed, 3/14 neutral). Strong agreement was confirmed by the committee 11/14 (79%; p = .0325).

The use of validated questionnaires (DN4, LANSS, CSI) that evaluate specific situations is recommended. (3/12 totally agreed, 8/12 partially agreed, 1/12 neutral). Strong agreement was confirmed by the committee 11/12 (92%; p = .0039).

Since the previous three points are rather ambiguous, there is a major need to create and validate a tailor-made physical examination approach for mixed pain (also see Chapter 3 below), that could be complemented by a newly developed mixed screening tool in the form of a validated questionnaire. This is even more important because most published studies have a very low level of evidence (4) with an equally low level of recommendation.

To overcome this, the consensus committee decided to reunite in the future to develop a new questionnaire explicitly for mixed pain. A prospective multicenter study should be conducted in Latin America to describe mixed pain conditions through the McGill pain questionnaire and to evaluate its use as a diagnostic tool in mixed pain (6/12 totally agreed, 3/12 partially agreed, 1/12 neutral, 2/12 partially disagreed). Strong agreement was confirmed by the committee 9/12 (75%; p = .0833) ().

Value of physical examination for the diagnosis of mixed pain

A thorough physical examination is very important during the diagnosing process of a patient. In mixed pain, it should be aiming to find different pain signaling pathways and pain components. Nociceptive, neuropathic, and nociplastic pain components may occur simultaneously or at different times during the same time course, one component or another being dominant at each moment and changing its magnitude and dominance over timeCitation14. It may be difficult to identify the different components. A thorough physical exam is therefore of utmost importanceCitation14.

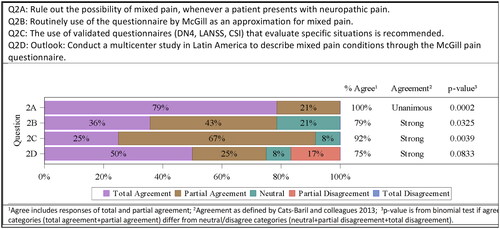

The human face is considered the main signaling system for displaying emotions and is hence often used in clinical pain assessments. It is a powerful means of diagnosis, particularly in the vulnerable population (e.g. infants, ventilated critically ill patients, patients with cognitive impairment), where it is not possible to get information directly from the patientCitation29. The Facial Action Coding System (FACS) can identify facial responses to pain via videos and was already used in both laboratory and clinical studiesCitation30. Assessment of facial expressions for the evaluation of pain in the vulnerable population was suggested to the consensus committee (4/14 totally agreed, 4/14 partially agreed, 3/14 neutral, 1/14 partially disagreed, 2/14 totally disagreed; grade of recommendation B, level of evidence 1+). The committee did not agree on this question 8/14 (57%; p = .5930). There was also no agreement to include the study of facial expressions into clinical practice (2/14 totally agreed, 6/14 partially agreed, 1/14 neutral, 2/14 partially disagreed, 3/14 totally disagreed). The committee did not agree on this question 8/14 (57%; p = .5930).

In the physical examination, the appreciation of pain of high intensity with more than one component at the same time suggests the suspicion of a mixed pain, with a pejorative prognosis (1/13 totally agreed, 4/13 partially agreed, 5/13 neutral, 1/13 partially disagreed, 2/13 totally disagreed; grade of recommendation A, level of evidence 2+). The committee did not agree on this question 5/13 (38%; p = .4054).

Quantitative sensory tests (QST) quantify the responses obtained to specific stimuli and allow the detection and quantification of nociceptive neuroplasticity. QSTs have been developed as a method of evaluation and analysis of somatosensory disturbances, complementary to conventional neurological examinationCitation31,Citation32. There is only low evidence for the use of QST in the assessment of pain in the literature; there seems to be no clinical benefit. Therefore, the use of QST to assess mixed pain is not recommended (5/14 totally agreed, 1/14 partially agreed, 3/14 neutral, 1/14 partially disagreed, 4/14 totally disagreed; grade of recommendation B, level of evidence 1+). The committee did not agree on this question 6/13 (43%; p = .4930).

Somatosensory evoked potentials (SSEP) help to assess whether proprioceptive sensory afferent pathways are disturbed and to determine their probable locationCitation33. Laser-evoked potentials have been used as an easy and reliable neurophysiological method to examine the function of subcortical nociceptive pathwaysCitation34. Functional disorders are characterized by the integrity of the nociceptive pathway and thereby show unattenuated laser SSEP. Thus, laser-evoked potentials help to differentiate between organic and functional pain syndromesCitation35. It is not advisable to use them in mixed pain, due to their functional character, unless we try to rule out any differential or previous organic alteration. The available evidence on evoked potentials assessing pain pathways is insufficient to make any recommendation (grade of recommendation D, level of evidence 4). The committee did therefore decide to not vote on this question ().

Value of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) in the diagnosis of mixed pain

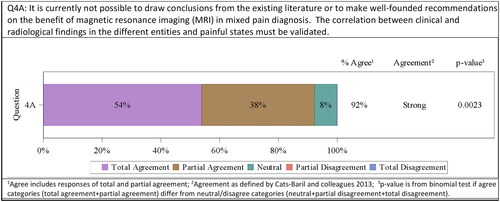

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a powerful tool for the diagnosis of different pain types. It can help to identify myopathic changes and thereby identify neuropathic pain, find the location of lesions, and thereby select the correct treatment, and exclude certain syndromic diagnosisCitation36. There are several advanced methods including or being based upon MRI: voxel-based morphometry (investigating focal differences in brain anatomyCitation37, diffusion tensor imaging (DTI, assessing the integrity of the white matterCitation38) magnetic resonance spectroscopy (evaluating metabolites and specific actions of neurotransmittersCitation39), and functional MRI (fMRI, indirectly measuring neuronal activityCitation40). Therefore, MRI can help to differentiate and identify mixed pain, besides being a non-invasive method. Nevertheless, it is currently not possible to draw conclusions from the existing literature or to make well-founded recommendations on the benefit of fMRI in mixed pain diagnosis. The correlation between clinical and fMRI findings in the different entities and painful states must be validated. In addition, despite all the advantages, it represents a significant burden for low-income countries like most countries in Latin America. All that does not allow recommending the indication of fMRI in Latin America for now, although it might represent a powerful tool in the future. This was agreed on by all the consensus meeting members (7/13 totally agreed, 5/13 partially agreed, 1/13 neutral). Strong agreement was confirmed by the committee 12/13 (92%; p = .0023) ().

Nonopioid analgesics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and opioids in the treatment of mixed pain

As described before, the definition and diagnosis of mixed pain are still not agreed on and described in its entirety. Its pathophysiology is also still undefined. That is why there are also no treatment guidelines existing, yet.

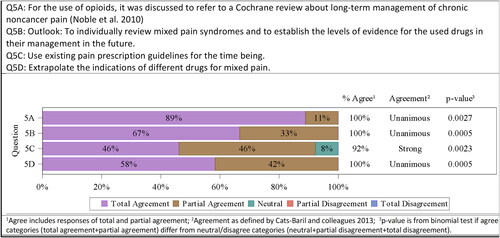

Indications and adverse events of paracetamol, steroids, caffeine (the most frequently used adjuvant of analgesics in Latin America), topical medications, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), selective Cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors, and minor and major opioids were presented. There is published data presenting the use of adjuvant analgesics, NSAIDs, and opioids in individual pain syndromes (e.g. joint, neuropathic, oncologic pain, etc.), which are understood to being supposedly of mixed nature. For those studies, the respective levels of evidence do exist. But there is no data on the use of medications particularly in mixed pain, why it was not possible to establish levels of evidence. The consensus committee, therefore, decided that it will individually review literature describing scenarios of mixed pain syndromes and to establish the levels of evidence for the used drugs in their management in the future (8/12 totally agreed, 4/12 partially agreed). Unanimous agreement was confirmed by the committee 12/12 (100%; p = .0005).

The analgesics ladder defined by the World Health Organization (WHO)Citation41 suggests to escalate the use of drugs in the treatment of pain as follows:

non-opioids with/without adjuvant analgesics in mild pain

opioids for mild and moderated pain + nonopioid with/without adjuvant analgesics in mild to moderate pain

opioids for moderate to severe pain + nonopioids with/without adjuvant analgesics in moderate to severe painCitation41.

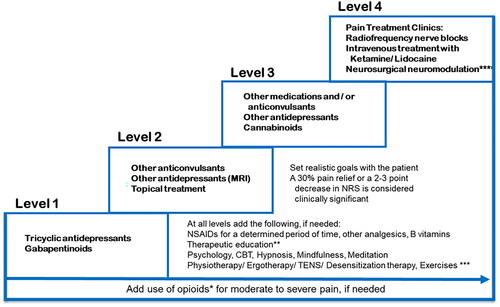

A 5-step adaptionCitation42 of the WHO analgesic ladder was used to propose lines of treatment observing the following points: (1) Follow the steps of the analgesic ladder according to pain intensity and always add adjuvants; (2) Use a fixed schedule; (3) Pay attention to detail; (4) Individually adjust to patient needs; (5) Administer orally or via the least invasive route. Weighing of adverse events versus the treatment’s benefit were emphasized. It was agreed to use the existing pain prescription guidelines (6/13 totally agreed, 6/13 partially agreed, 1/13 neutral) for the time being. Strong agreement was confirmed by the committee 12/13 (92%; p = .0023).

And since again no specific studies and information on mixed pain could be identified, it was agreed by the consensus members, to extrapolate the indications of different drugs for mixed pain (7/12 totally agreed, 5/12 partially agreed). Unanimous agreement was confirmed by the committee 12/12 (100%; p = .0005).

For the use of opioids, it was discussed to refer to an existing Cochrane review by Noble et al. about long-term management of chronic noncancer pain (Noble et al.Citation43; 8/9 totally agreed, 1/9 partially agreed, the rest of the committee members did not vote). Unanimous agreement was confirmed by the committee 9/9 (100%; p = .0027) ().

Neuromodulators in the treatment of mixed pain

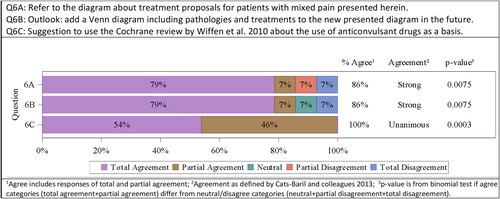

Whenever the aforementioned treatment ladder by the WHO culminating in the use of opioids fails to help the patient, stronger medications are suggested. Neuromodulators like antidepressants and anticonvulsants are the most widely used psychotropic drugs in the treatment of pain and are usually used as co-analgesics. They potentiate the effects of NSAIDs and opioids. As for the other chapters, no specific guidance or literature focusing on mixed pain could be identified. Therefore, an extrapolation of existing data for neuropathic pain or in indications that involve mixed pain like osteoarthrosis and fibromyalgia was carried out. A treatment guidance for mixed pain based on the assessment of the bibliography and international guidelines for neuropathic painCitation42, was adopted. The diagram stipulates an escalation scenario of 4 levels (see ). The majority of consensus members agreed on the recommendation of this treatment guidance (11/14 totally agreed, 1/14 partially agreed, 1/14 partially disagreed, 1/14 totally disagreed). Strong agreement was confirmed by the committee 12/14 (86%; p = .0075).

It was decided, to add a Venn diagram including pathologies and treatments to in the future and thereby generate an overall and easy-to-understand treatment guide of mixed pain for all practitioners (11/14 totally agreed, 1/14 partially agreed, 1/14 neutral, 1/14 totally disagreed). Strong agreement was confirmed by the committee 12/14 (86%; p = .0075).

The systematic Cochrane review carried out by Wiffen et al.Citation44 was assessed to get an overview on the efficacy of different neuropathic pain treatments on basis of numbers needed to treat (NNT). NNT values are calculated for the proportion of subjects who had at least 50% pain relief over 4–6 h when compared with placebo. The lower the NNT value, the better the efficacy. The gold standard Carbamazepine showed the best efficacy (NNT = 1.7), while Gabapentin and Pregabalin had relatively high numbers (NNT 6–8 and 3.8–11.1, respectively) despite being widely usedCitation44. It was suggested to use the Cochrane review by Wiffen et al.Citation44 about the use of anticonvulsant drugs for acute and chronic pain as a basis (7/13 totally agreed, 6/13 partially agreed). Unanimous agreement was confirmed by the committee 13/13 (100%; p = .0003) ().

The role of B vitamins in the treatment of mixed pain

The use of vitamins B1, B6, and B12 in the treatment of mixed pain has been discussed for quite a while, due to their involvement in the physiopathology of several pain mechanisms. Antinociceptive activity, regulation of inflammatory mediators in various inflammatory pain models, and a role in neuron regeneration have been described, to name a fewCitation45–53. The role of vitamin B1, B6, and B12 in pain relief either given alone or as an adjuvant to other drugs for analgesia was therefore also reviewed for this consensus meeting. Studies presenting the use of B vitamins in mixed pain scenarios (i.e. pathologies that are typically of mixed pain nature) were included since again no studies explicitly dealing with mixed pain could be identified. Those, which were used as a basis for phrasing the final recommendations for this chapter are described hereafter.

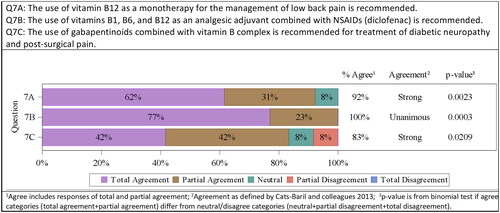

Two controlled, randomized, clinical studies investigating the use of intramuscular vitamin B12 administration in patients with chronic low back pain and a low risk of biasCitation54 were identifiedCitation55,Citation56. Both used a visual analogue scale (VAS) pain score for the evaluation of pain. Those patients treated intramuscularly with vitamin B12 showed a significant improvement of VAS pain scores when compared to placebo. Based on those two studies the consensus committee agreed, that the use of vitamin B12 as a monotherapy for the management of low back pain is recommended (level of evidence 1+ for this indication with a grade B recommendation; 8/13 totally agreed, 4/13 partially agreed, 1/13 neutral). Strong agreement was confirmed by the committee 12/13 (92%; p = .0023).

The benefits of using vitamins B1, B6, and B12 combined with NSAIDs, mainly diclofenac, in pain management has already been discussed for several years. In the current approach, a meta-analysis was pointed out, which included 4 studies (1169 patients) in acute low back painCitation54. All 4 studies compared the use of the combination therapy (B vitamins + diclofenac) with the use of diclofenac only. More patients in the combination therapy groups discontinued study therapy earlier than expected due to complete pain reliefCitation57–60. Two other studies confirmed that finding in other indications (lower limb closed fractures and severe osteoarthritisCitation61,Citation62. Taken together, the analgesia obtained through the combination of vitamins B1, B6, and B12 with diclofenac showed a high level of scientific evidence (1++, high-quality meta-analysis, systematic reviews of clinical trials or high-quality clinical trials with very low risk of biasCitation54,Citation61,Citation62, which supports its use as an analgesic adjuvant when combined with NSAIDs (diclofenac) (10/13 totally agreed, 3/13 partially agreed). Unanimous agreement was confirmed by the committee 13/13 (100%; p = .0003).

No reliable sources supporting the recommendation of combined use of B vitamins with opioids were found, but two controlled, clinical studies describing the positive effects of the use of gabapentinoids combined with vitamin B complex were identified. One study compared the combination of gabapentin + vitamins B1 and B12 with pregabalin in patients with diabetic neuropathy. The level of evidence was determined as 2++ since no direct comparison with gabapentin as monotherapy was performed. The use of the combination therapy was not inferior to the use of pregabalinCitation63. The second study compared the use of gabapentin in combination with B vitamins (B1, B2, B3, B6) in women after undergoing a caesarean section with the use of gabapentin only. Women on combination therapy consumed less analgesics and experienced a lower pain intensity (assessed as VAS scores) compared to monotherapy (level of evidence 1+)Citation64 Based on those two studies the consensus committee voted as follows on the recommendation of the use of B vitamins in combination with gabapentinoids in diabetic neuropathy and post-surgical pain: 5/12 totally agreed, 5/12 partially agreed, 1/12 neutral, 1/12 partially disagreed (grade of recommendation C). Strong agreement was confirmed by the committee 10/12 (83%; p = .0209) ().

Cognitive behavioral therapy in the treatment of mixed pain

The consensus committee elaborated the value of virtual reality (VR), meditation, desensitization, and reprogramming as non-pharmacological approaches in the treatment of pain. As for the other chapters, no specific guidance or literature focusing on mixed pain could be identified. Therefore, studies in pain, in general, were used as an approximation.

VR in the treatment of pain works via distraction from pain using active cognitive processing to divert attention through the creation of sensorial illusions, improvement of analgesia by reducing visual stimuli associated with the painful procedure, and alteration of the way the brain processes pain and produces analgesiaCitation65–68. Immersive virtual reality (immersive VR) is the presentation of an artificial environment that replaces users’ real-world surroundings convincingly enough, that they are able to suspend disbelief and fully engage with the created environment. Non-immersive VR is a type of VR technology that provides users with a computer-generated environment without a feeling of being immersed in the virtual world. The main characteristic of a non-immersive VR system is that users can keep control over physical surrounding while being aware of what is going on around them, including sounds, visuals, and hapticsCitation69. The levels of recommendations for the different therapy approaches were defined with the following outcomes: There is strong evidence (1a) that the use of immersive VR reduces acute pain, but only limited evidence (2a) on its efficacy in chronic pain. No evidence (level of evidence 4) that non-immersive VR reduces acute or chronic pain was found. There was limited evidence (level of evidence 2a) suggesting that immersive and non-immersive VR can reduce the intensity of acute pain.

Meditation is a state in which consciousness is raised to new heights and is essentially a state of being, or rather several related states of being and consciousnessCitation70. Short periods of meditation practice (less than a week) can already significantly increase personal pain tolerability by 13%Citation70. There is solid evidence that meditation significantly reduces pain. It has been documented in a randomized controlled trial that meditation produced a greater decrease in pain in patients with chronic low back pain, compared to cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). Different studies have been established, with good results in favor of meditation in different indications (fibromyalgia, headache, chronic pelvic pain, irritable bowel syndrome, chronic low back pain)Citation70–72. There are systematic reviews and meta-analyses that conclude that meditation significantly improves pain, depression, and quality of life. Randomized experimental studies reported that spiritual meditation has an additional unique effect, reducing pain (Level of recommendation 1-BCitation73–75.

Systematic desensitization, reprogramming, and mindfulness were also shortly presented and discussed, but no recommendations were stipulated to them since there was not enough evidence.

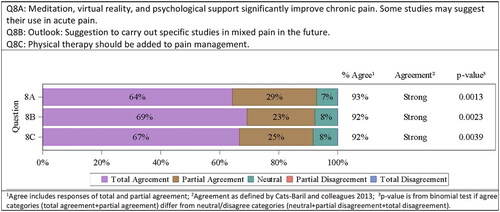

After a vivid discussion, the consensus agreed that VR, meditation, and psychological support were the means with the strongest evidence. Therefore, recommendations were only expressed and voted for those topics, as follows: Systematic reviews and meta-analyses deliver sufficient evidence that meditation, VR, and psychological support significantly improve chronic pain. There are studies that may suggest their use in acute pain. All consensus committee members either totally or partially agreed on this recommendation (9/14 totally agreed, 4/14 partially agreed, 1/14 neutral). Strong agreement was confirmed by the committee 13/14 (93%; p = .0013). Existing data was again for acute or chronic pain in general. It was therefore suggested to carry out studies in mixed pain specifically (9/13 totally agreed, 3/13 partially agreed, 1/13 neutral). Strong agreement was confirmed by the committee 12/13 (92%; p = .0023). Moreover, it was discussed whether physical therapy should be added to pain management. None of the consensus committee members disagreed with that suggestion (8/12 totally agreed, 3/12 partially agreed, 1/12 neutral). Strong agreement was confirmed by the committee 11/12 (92%; p = .0039) ().

Figure 10. Results of statistical evaluation of the topic “Cognitive behavioral therapy in the treatment of mixed pain”.

A summary of the recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of mixed pain in Latin America can be found in .

Table 3. Overview of recommendations and key messages agreed on by the consensus committee.

Conclusions

There is an increasing interest within the medical community on the topic of mixed pain. Every person is different and will respond differently to situations, interventions, surgeries, and medications. This is even more the case in mixed pain scenarios, where different pain pathways are involved. Hence, it is of utmost importance to adjust treatments and diagnosing for each individual. A combination of different above-described treatments depending on the patient’s need should be customized. All social, economic, cultural, regional, and personal circumstances have to be taken into account. Carrying out meetings and stipulating recommendations in a geographical, historical, and cultural environment, as done in this current approach for Latin America, is therefore essential.

Despite referring to the specific situation in Latin America, the discussion of all the conflictive points dealt with in this study, the agreements reached, and the recommendations made after all this are applicable and can contribute to the global conceptual development of mixed pain. The concise definition, the relevance of anamnesis in the diagnosis of mixed pain, the recommendation to use self-administered questionnaires, the recommendation to routinely use the McGill questionnaire, the non-recommendation of QST in the evaluation of mixed pain, the criticism to the current use of fMRI in the assessment of mixed pain, the need of specific guidelines to manage the mixed pain, in the interim the extrapolation of the use of the different therapeutic procedures taking into account the existing data regarding the respective components of mixed pain, and the complement to the drugs represented by other different measures, provide some improvement in the general knowledge of mixed pain.

There is an urgent need for validated diagnostic tools and mixed pain tailor-made physical examination approaches. Moreover, drugs and treatment regimens focusing on a mixed nature of pain need to be developed. To do so, clarification and investigation on the physiopathology and mechanisms of mixed pain are needed. Overall, there is a lot of work to be done in the future! This includes planning and set-up of future studies and assessments explicitly in patients with mixed pain and prospective consensus meetings should be held to tackle open questions and topics.

Transparency

Author contributions

CCO, CPH, FFV, and MFF were involved in the conception and design of the study and defined the main topics to being addressed for the consensus. All the authors participated in the analysis, interpretation, and discussion of the data; the drafting of the paper or revising it critically for intellectual content; the final approval of the version to be published; and that all authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the following persons: Dr. Rainer Freynhagen (Department of Anesthesiology, Critical Care Medicine, Pain Therapy and Palliative Care, Benedictus Hospital Tutzing, Tutzing, Germany) for motivating this study; Dr. A. Pérez-Torres (APT) and Dr. E. Aguado (EA) for performing the literature review; Dr. Kerstin Eckart (Munich, Germany) for providing medical writing and editing support for this manuscript.

Declaration of funding

Medical writing and editing services were sponsored by P&G Health Germany GmbH.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

Drs. A. Lara-Solares, A. Manzano-García, C. P. Helito, C. Calderon-Ospina, D. Ruiz-Rodriguez, M. Fernandez-Fairen, F. Fernandez-Villacorta, J. Chen, L. Lopez-Almejo, M. Duarte-Vega, and M. Puello-Vales are consultants and speakers to Procter & Gamble. Drs. A. Servin-Caamaño, E. Hernandez, F. Gomez-Garcia, G. Vargas-Schaffer, and G. Salas-Morales do not have any conflicts of interest to declare. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

References

- American Pain Society Quality of Care Committee. Quality improvement guidelines for the treatment of acute pain and cancer pain. American Pain Society Quality of Care Committee. JAMA. 1995;274(23):1874–1880.

- Max MB. Improving outcomes of analgesic treatment: is education enough? Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(11):885–889.

- Raja SN, Carr DB, Cohen M, et al. The revised international association for the study of pain definition of pain: concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain. 2020;161(9):1976–1982.

- Junker U. Chronic pain: the “mixed pain concept” as a new rational. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2004;101(20):1393.

- Trouvin AP, Perrot S. New concepts of pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2019;33(3):101415.

- Stanos S, Brodsky M, Argoff C, et al. Rethinking chronic pain in a primary care setting. Postgrad Med. 2016;128(5):502–515.

- Rief W, Kaasa S, Jensen R, et al. New proposals for the international classification of diseases-11 revision of pain diagnoses. J Pain. 2012;13(4):305–316.

- Picelli A, Buzzi MG, Cisari C, et al. Headache, low back pain, other nociceptive and mixed pain conditions in neurorehabilitation. Evidence and recommendations from the Italian Consensus Conference on Pain in Neurorehabilitation. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2016;52(6):867–880.

- Phillips K, Clauw DJ. Central pain mechanisms in chronic pain states–maybe it is all in their head. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2011;25(2):141–154.

- Ibor PJ, Sánchez-Magro I, Villoria J, et al. Mixed pain can be discerned in the primary care and orthopedics settings in Spain: a large cross-sectional study. Clin J Pain. 2017;33(12):1100–1108.

- Bonezzi C, Fornasari D, Cricelli C, et al. Not all pain is created equal: basic definitions and diagnostic work-up. Pain Ther. 2020;9(Suppl 1):1–15.

- Freynhagen R, Rey R, Argoff C. When to consider “mixed pain”? The right questions can make a difference! Curr Med Res Opin. 2020;36(12):2037–2046.

- Cohen SP, Vase L, Hooten WM. Chronic pain: an update on burden, best practices, and new advances. Lancet. 2021;397(10289):2082–2097.

- Freynhagen R, Parada HA, Calderon-Ospina CA, et al. Current understanding of the mixed pain concept: a brief narrative review. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35(6):1011–1018.

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. SIGN 50: a guideline developer’s handbook. 2019. Edinburgh: SIGN. Available from: http://www.sign.ac.uk

- Cats-Baril W, Gehrke T, Huff K, et al. International consensus on periprosthetic joint infection: description of the consensus process. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(12):4065–4075.

- Tamburin S, Paolucci S, Magrinelli F, et al. The italian consensus conference on pain in neurorehabilitation: rationale and methodology. J Pain Res. 2016;9:311–318.

- Bennett MI, Attal N, Backonja MM, et al. Using screening tools to identify neuropathic pain. Pain. 2007;127(3):199–203.

- Hasvik E, Haugen AJ, Gjerstad J, et al. Assessing neuropathic pain in patients with low back-related leg pain: comparing the painDETECT questionnaire with the 2016 NeuPSIG grading system. Eur J Pain. 2018;22(6):1160–1169.

- Vicente Herrero MT, Delgado Bueno S, Bandrés Moyá F, et al. Valoración del dolor. Revisión comparativa de escalas y cuestionarios. Rev Esp Soc Dolor. 2018;25:228–236.

- Masedo AI, Esteve R. Some empirical evidence regarding the validity of the Spanish version of the McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ-SV). Pain. 2000;85(3):451–456.

- Lázaro C, Caseras X, Whizar-Lugo VM, et al. Psychometric properties of a Spanish version of the McGill Pain Questionnaire in several Spanish-speaking countries. Clin J Pain. 2001;17(4):365–374.

- Ubillos-Landa S, García-Otero R, Puente-Martínez A. Validation of an instrument for measuring chronic pain in nursing homes. An Sist Sanit Navar. 2019;42(1):19–30.

- Alonso J, Prieto L, Anto JM. The Spanish version of the SF-36 Health Survey (the SF-36 health questionnaire): an instrument for measuring clinical results. Med Clin. 1995;104(20):771–776.

- De Andrés J, Pérez-Cajaraville J, Lopez-Alarcón MD, et al. Cultural adaptation and validation of the painDETECT scale into Spanish. Clin J Pain. 2012;28(3):243–253.

- Perez C, Galvez R, Huelbes S, et al. Validity and reliability of the Spanish version of the DN4 (douleur neuropathique 4 questions) questionnaire for differential diagnosis of pain syndromes associated to a neuropathic or somatic component. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:66.

- Pérez C, Gálvez R, Insausti J, et al. Linguistic adaptation and Spanish validation of the LANSS (Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs) scale for the diagnosis of neuropathic pain. Med Clin. 2006;127(13):485–491.

- Cuesta-Vargas AI, Roldan-Jimenez C, Neblett R, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation and validity of the Spanish central sensitization inventory. Springerplus. 2016;5(1):1837.

- Lautenbacher S, Kunz M. Assessing pain in patients with dementia. Anaesthesist. 2019;68(12):814–820.

- Kunz M, Meixner D, Lautenbacher S. Facial muscle movements encoding pain-a systematic review. Pain. 2019;160(3):535–549.

- Haanpää M, Attal N, Backonja M, et al. NeuPSIG guidelines on neuropathic pain assessment. Pain. 2011;152(1):14–27.

- Uddin Z, MacDermid JC. Quantitative sensory testing in chronic musculoskeletal pain. Pain Med. 2016;17(9):1694–1703.

- Tsai TM, Tsai CL, Lin TS, et al. Value of dermatomal somatosensory evoked potentials in detecting acute nerve root injury: an experimental study with special emphasis on stimulus intensity. Spine. 2005;30(18):E540–E546.

- Valeriani M, Pazzaglia C, Cruccu G, et al. Clinical usefulness of laser evoked potentials. Neurophysiol Clin. 2012;42(5):345–353.

- Truini A, Galeotti F, Romaniello A, et al. Laser-evoked potentials: normative values. Clin Neurophysiol. 2005;116(4):821–826.

- Du R, Auguste KI, Chin CT, et al. Magnetic resonance neurography for the evaluation of peripheral nerve, brachial plexus, and nerve root disorders. J Neurosurg. 2010;112(2):362–371.

- Martin L, Borckardt JJ, Reeves ST, et al. A pilot functional MRI study of the effects of prefrontal rTMS on pain perception. Pain Med. 2013;14(7):999–1009.

- Seminowicz DA, Shpaner M, Keaser ML, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy increases prefrontal cortex gray matter in patients with chronic pain. J Pain. 2013;14(12):1573–1584.

- Robbins NM, Shah V, Benedetti N, et al. Magnetic resonance neurography in the diagnosis of neuropathies of the lumbosacral plexus: a pictorial review. Clin Imaging. 2016;40(6):1118–1130.

- Da Silva JT, Seminowicz DA. Neuroimaging of pain in animal models: a review of recent literature. Pain Rep. 2019;4(4):e732.

- Ventafridda V, Saita L, Ripamonti C, et al. WHO guidelines for the use of analgesics in cancer pain. Int J Tissue React. 1985;7(1):93–96.

- Vargas-Schaffer G. Is the WHO analgesic ladder still valid? Twenty-four years of experience. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56(6):514–517. e202-e205.

- Noble M, Treadwell JR, Tregear SJ, et al. Long-term opioid management for chronic noncancer pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;2010(1):CD006605.

- Wiffen PJ, Collins S, McQuay HJ, et al. WITHDRAWN. Anticonvulsant drugs for acute and chronic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;1:CD001133.

- Wang ZB, Gan Q, Rupert RL, et al. Thiamine, pyridoxine, cyanocobalamin and their combination inhibit thermal, but not mechanical hyperalgesia in rats with primary sensory neuron injury. Pain. 2005;114(1):266–277.

- Zhang M, Han W, Zheng J, et al. Inhibition of hyperpolarization-activated cation current in medium-sized DRG neurons contributed to the antiallodynic effect of methylcobalamin in the rat of a chronic compression of the DRG. Neural Plast. 2015;2015:1–13.

- Song XS, Huang ZJ, Song XJ. Thiamine suppresses thermal hyperalgesia, inhibits hyperexcitability, and lessens alterations of sodium currents in injured, dorsal root ganglion neurons in rats. Anesthesiology. 2009;110(2):387–400.

- Dakshinamurti K, Sharma SK, Bonke D. Influence of B vitamins on binding properties of serotonin receptors in the CNS of rats. Klin Wochenschr. 1990;68(2):142–145.

- Xu J, Wang W, Zhong XX, et al. EXPRESS: methylcobalamin ameliorates neuropathic pain induced by vincristine in rats: effect on loss of peripheral nerve fibers and imbalance of cytokines in the spinal dorsal horn. Mol Pain. 2016;12:174480691665708.

- Vesely DL. B complex vitamins activate rat guanylate cyclase and increase cyclic GMP levels. Eur J Clin Invest. 1985;15(5):258–262.

- Yu CZ, Liu YP, Liu S, et al. Systematic administration of B vitamins attenuates neuropathic hyperalgesia and reduces spinal neuron injury following temporary spinal cord ischaemia in rats. Eur J Pain. 2014;18(1):76–85.

- Geller M, Oliveira L, Nigri R, et al. B vitamins for neuropathy and neuropathic pain. Vitam Miner. 2017;06(02):1–7.

- Gazoni FM, Malezan WR, Santos FC. B complex vitamins for analgesic therapy. Rev Dor. São Paulo. 2016;17(1):52–56.

- Calderon-Ospina CA, Nava-Mesa MO, Arbeláez Ariza CE. Effect of combined diclofenac and B vitamins (thiamine, pyridoxine, and cyanocobalamin) for low back pain management: systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Med. 2020;21(4):766–781.

- Chiu CK, Low TH, Tey YS, et al. The efficacy and safety of intramuscular injections of methylcobalamin in patients with chronic nonspecific low back pain: a randomised controlled trial. Singapore Med J. 2011;52(12):868–873.

- Mauro GL, Martorana U, Cataldo P, et al. Vitamin B12 in low back pain: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2000;4(3):53–58.

- Bruggemann G, Koehler CO, Koch EM. Results of a double-blind study of diclofenac + vitamin B1, B6, B12 versus diclofenac in patients with acute pain of the lumbar vertebrae. A multicenter study. Klin Wochenschr. 1990;68(2):116–120.

- Kuhlwein A, Meyer HJ, Koehler CO. Reduced diclofenac administration by B vitamins: results of a randomized double-blind study with reduced daily doses of diclofenac (75 mg diclofenac versus 75 mg diclofenac plus B vitamins) in acute lumbar vertebral syndromes. Klin Wochenschr. 1990;68(2):107–115.

- Mibielli MA, Geller M, Cohen JC, et al. Diclofenac plus B vitamins versus diclofenac monotherapy in lumbago: the DOLOR study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25(11):2589–2599.

- Vetter G, Brüggemann G, Lettko M, et al. Shortening diclofenac therapy by B vitamins. Results of a randomized double-blind study, diclofenac 50 mg versus diclofenac 50 mg plus B vitamins, in painful spinal diseases with degenerative changes. Z Rheumatol. 1988;47(5):351–362.

- Magana-Villa MC, Rocha-González HI, Fernández del Valle-Laisequilla C, et al. B-vitamin mixture improves the analgesic effect of diclofenac in patients with osteoarthritis: a double blind study. Drug Res. 2013;63(6):289–292.

- Ponce-Monter HA, Ortiz MI, Garza-Hernández AF, et al. Effect of diclofenac with B vitamins on the treatment of acute pain originated by lower-limb fracture and surgery. Pain Res Treat. 2012;2012:104782.

- Mimenza Alvarado A, Aguilar Navarro S. Clinical trial assessing the efficacy of gabapentin plus B complex (B1/B12) versus pregabalin for treating painful diabetic neuropathy. J Diabetes Res. 2016;2016:4078695.

- Khezri MB, Nasseh N, Soltanian G. The comparative preemptive analgesic efficacy of addition of vitamin B complex to gabapentin versus gabapentin alone in women undergoing cesarean section under spinal anesthesia: a prospective randomized double-blind study. Medicine. 2017;96(15):e6545.

- Lin HT, Li YI, Hu WP, et al. A scoping review of the efficacy of virtual reality and exergaming on patients of musculoskeletal system disorder. JCM. 2019;8(6):791.

- Gold JI, Belmont KA, Thomas DA. The neurobiology of virtual reality pain attenuation. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2007;10(4):536–544.

- Venuturupalli RS, Chu T, Vicari M, et al. Virtual reality-based biofeedback and guided meditation in rheumatology: a pilot study. ACR Open Rheuma. 2019;1(10):667–675.

- Gazerani P. Virtual reality for pain control—virtual or real? US Neurology. 2016;12(02):82–83.

- Le May S, Tsimicalis A, Noel M, et al. Immersive virtual reality vs. non-immersive distraction for pain management of children during bone pins and sutures removal: a randomized clinical trial protocol. J Adv Nurs. 2021;77(1):439–447.

- Zeidan F, Baumgartner JN, Coghill RC. The neural mechanisms of mindfulness-based pain relief: a functional magnetic resonance imaging-based review and primer. Pain Rep. 2019;4(4):e759.

- Kingston J, Chadwick P, Meron D, et al. A pilot randomized control trial investigating the effect of mindfulness practice on pain tolerance, psychological well-being, and physiological activity. J Psychosom Res. 2007;62(3):297–300.

- Turner JA, Anderson ML, Balderson BH, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic low back pain: similar effects on mindfulness, catastrophizing, self-efficacy, and acceptance in a randomized controlled trial. Pain. 2016;157(11):2434–2444.

- Sollgruber A, Bornemann-Cimenti H, Szilagyi IS, et al. Spirituality in pain medicine: a randomized experiment of pain perception, heart rate and religious spiritual well-being by using a single session meditation methodology. PLOS One. 2018;13(9):e0203336.

- Hilton L, Hempel S, Ewing BA, et al. Mindfulness meditation for chronic pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51(2):199–213.

- Bawa FLM, Mercer SW, Atherton RJ, et al. Does mindfulness improve outcomes in patients with chronic pain? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2015;65(635):e387–e400.