Abstract

Objectives

EA 575 (Prospan) is a herbal medicine containing a dried extract of ivy leaves (drug extract ratio 5–7.5:1; extraction solvent, 30% ethanol). Although widely used for the treatment of cough, there remains a lack of clarity on the effects of EA 575 in children. This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of EA 575 in pediatric patients with cough, via a literature review and expert survey.

Methods

A MEDLINE/PubMed database search was performed to identify articles evaluating the efficacy and tolerability of EA 575 in pediatric patients with cough. An online survey of international pediatric cough experts was conducted to gather expert opinion regarding the use of EA 575 for pediatric cough.

Results

Ten controlled clinical trials and nine observational studies were identified. Controlled trials reported improvements in lung function and subjective cough symptoms with EA 575, while observational studies indicated overall favorable efficacy. EA 575 was generally well tolerated, with a low incidence of adverse events in children of all ages, including those aged <1 year. Survey responses from ten experts aligned with findings from the reviewed studies. Most experts agreed that EA 575 may improve quality of life, and highlighted its potential benefits on sleep.

Conclusions

EA 575 has minimal side effects in pediatric patients with cough, as demonstrated by large, real-world studies. EA 575 may provide clinical benefits in pediatric patients; however, more robust clinical trials are needed to confirm its efficacy.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

EA 575 (Prospan) is a medicine containing a dried extract of ivy leaves that is used to treat coughs. The aim of this review was to evaluate the available published information on the health benefits and side effects of EA 575 in children with coughs. We also conducted a survey of doctors who treat children with coughs. We found information from ten research trials that compared EA 575 with another cough medicine or a “dummy medicine”. Although these studies included only a small number of children, the results suggested that children’s breathing and cough symptoms may improve with EA 575 treatment. We also found nine studies that included children being treated in normal clinical situations and not in a research setting. Most of the children included in these studies and their doctors thought that EA 575 treatment was beneficial. A low number of side effects was reported in children of all ages, including in infants aged <1 year. Survey responses from ten doctors generally agreed with the findings from the research studies. Most of the doctors thought that EA 575 may improve quality of life. Improved sleep was commonly mentioned by doctors. Overall, our findings indicate that EA 575 has minimal side effects in children; we call for more research on the benefits of EA 575 on cough symptoms in children.

Introduction

Dried leaf extracts of common ivy (Hedera helix L.) are well established in the treatment of certain respiratory diseases – particularly when cough is a symptomCitation1. EA 575 (Prospan) is a herbal medicinal product containing a dried extract of ivy leaves (drug extract ratio [DER] 5–7.5:1; extraction solvent, 30% ethanol)Citation2,Citation3, which is manufactured in a range of dosage forms including syrup, drops, and effervescent tablets. Ivy leaf dry extracts with different DERs are also available, but are not considered therapeutically equivalentCitation4.

Ivy leaf dry extracts contain triterpene saponins, flavonoids, phenolic acids and polyacetylenesCitation5. In vitro studies indicate that the saponin, α-hederin, is one of the main active compounds in ivy leaf extractsCitation6–8. α-hederin is thought to inhibit the internalization of β2-adrenergic receptors on alveolar type II cells and human airway smooth muscle cells, resulting in increased β-adrenergic responsiveness in the respiratory tractCitation6,Citation7. Ivy leaf dry extract EA 575 is also the first phytomedicine for which biased β2-adrenergic receptor activation has been demonstratedCitation9. G protein-biased signaling results in elevated cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels, leading to surfactant secretion (which may reduce the viscosity of mucus and aid mucociliary clearance) and bronchodilation (which reduces airway resistance), thought to manifest clinically as secretolytic and bronchospasmolytic effectsCitation6,Citation8–14. Furthermore, in vitro studies indicate that EA 575 may have anti-inflammatory propertiesCitation9,Citation15,Citation16. Taken together, the actions of EA 575 on multiple cough triggers – mucus, bronchoconstriction, and inflammation – may account for the overall cough-relieving effect observed in clinical practice.

Accumulated data from clinical trials of EA 575 in mixed populations of adults and children support its efficacy on cough symptoms and its favorable tolerability profileCitation3,Citation17. However, no comprehensive overview of the clinical benefits and possible side effects of EA 575 in the pediatric population, specifically, is available. The aim of this review was to evaluate published EA 575 studies in order to summarize the efficacy and tolerability of EA 575 in pediatric patients with acute or chronic cough. Additional insights regarding the potential clinical benefits of EA 575 in pediatric patients treated in real-world clinical practice were sought from international experts using an online survey.

Methods

Literature review search strategy

A literature review was conducted to identify published studies evaluating the efficacy and tolerability of EA 575 in pediatric patients with cough due to various causes. Any comparator, outcome measure, and study design was eligible. The review comprised a search of the MEDLINE/PubMed database, supported by additional articles known to the authors. The following search terms were used: (“EA 575” or “Prospan” or “ivy leaf” or “ivy leaves”) AND (pediatric or children). No limits on article language were applied. Early (before 1992) non-controlled studies were excluded as the European Medicines Agency (EMA) considers their methodology to be inadequate to show the efficacy of currently marketed productsCitation1. The search was performed on 19 May 2020.

Questionnaire

Expert opinion on EA 575 was collected as part of a 30-minute online questionnaire that was designed by the authors (and reviewed by the sponsor) to answer the following research question: “According to international experts, what are the therapeutic principles for, and unmet needs in, the treatment of cough in pediatric patients?” Full details of the questionnaire and the target audience (healthcare professionals with expertise in the area of pediatric cough) have been publishedCitation18. Briefly, the questionnaire comprised an introductory section to assess eligibility and obtain informed consent; sections on general therapeutic principles and unmet needs (previously reportedCitation18); and a section on the use of EA 575 for pediatric cough (reported here). A mix of open and closed questions were used. The questionnaire is provided as Supplementary file 1.

The questionnaire was designed and distributed in accordance with the Market Research Society (MRS) Code of Conduct; formal ethics approval is not required for market research. Participating experts gave digital written informed consent prior to starting the questionnaire. Questionnaire responses were anonymous, and no information was requested that would allow individuals to be identified.

Data were analyzed using Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA). For quantitative questions, means and numbers/percentages were calculated, as appropriate. No statistical comparisons were conducted due to the descriptive nature of the study and the small sample size.

Results

Literature review

A total of 19 articles, published between 1996 and 2020, and reporting the results of controlled clinical trials (n = 10) or observational studies (n = 9) with EA 575 were identified in the literature review. The trials/studies were conducted across six different countries/regions (Czech Republic, Germany, Slovenia, Switzerland, Ukraine, and Latin America).

Efficacy of EA 575 in controlled clinical trials

The designs of the controlled clinical trials (a mixture of randomized double-blind and open-label) and their results are summarized in . The trials assessed the efficacy of EA 575 in children with acute or chronic respiratory diseases including acute bronchitis, chronic obstructive respiratory disease, and bronchial asthmaCitation1,Citation19–26,Citation28. Most trials enrolled 20–70 children, although Cwientzek et al. enrolled 201 childrenCitation26. Typically, EA 575 was administered as a syrup, and the most common treatment duration was 7–10 days (full range, 3–30 days). The effects of EA 575 on cough were assessed through subjective measures including patient/parent- or clinician-rated global assessments of efficacy, and changes in specific symptoms, such as cough frequency, shortness of breath, expectoration, and respiratory pain. Most trials also used spirometry to assess the effects of EA 575 on lung function, often accompanied by body plethysmography.

Table 1. Summary of controlled clinical trials of EA 575 in pediatric patients.

Two publications described double-blind, placebo-controlled trials in children with bronchial asthmaCitation21,Citation28. Mansfeld et al.Citation21 found no differences in the occurrence or intensity of patient/parent-reported shortness of breath, or in the description of cough, between EA 575 and placebo. However, a clinically relevant and statistically significant reduction in the primary outcome – change in airway resistance (RAW) from baseline to Day 3 – was reported in children who received EA 575 (p < 0.01 versus baseline; p < 0.05 versus placebo)Citation21. In contrast, Zeil et al.Citation28 reported a lack of statistically significant improvement with EA 575 versus placebo in forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and maximal expiratory flow at 75–25% of the vital capacity (MEF75–25) before bronchodilation from baseline to Day 28–30 (primary outcomes). Significant improvements from baseline to Day 28–30 with EA 575 were reported for some secondary endpoints (e.g. absolute change in MEF75–25 before bronchodilation) but not for RAW measured before or after bronchodilationCitation28.

Three publications described active-controlled trials in children with acute respiratory diseasesCitation24,Citation25 and chronic respiratory diseasesCitation22,Citation24. In children with acute respiratory diseases, reduction in productive cough and subjective improvement of cough symptoms (assessed by clinicians and/or documented by patients) were similar following treatment with EA 575 syrup and with the mucolytic drugs ambroxol and acetylcysteineCitation24,Citation25. Statistically significantly greater improvements in respiratory parameters were observed with EA 575 versus acetylcysteine in children with acute bronchitisCitation25. In children with chronic obstructive bronchitis, respiratory parameters improved with EA 575 and acetylcysteine, with changes in FEV1 and peak expiratory flow (PEF) favoring EA 575Citation22. In another study, respiratory velocity parameters normalized in most children with obstructive respiratory diseases who received EA 575 for 7 days, but worsened with ambroxolCitation24. With EA 575 treatment, respiratory parameters normalized within 6–7 days for children with acute bronchitis, and within 9–11 days for children with bronchopneumonia or exacerbation of bronchial asthmaCitation24.

In three trials comparing the efficacy of different ivy leaf extracts, EA 575 decreased the severity of bronchitis (assessed by the Clinical Global Impression scale, the Bronchitis Severity Score, or a Visual Analogue Scale) to a similar extent to other ivy leaf extracts, including Valverde (DER 3–6:1) and Hedelix (DER 2.2–2.9:1)Citation1,Citation23,Citation26.

Finally, two trials compared the efficacy of different EA 575 dosage formsCitation19,Citation20. In children with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), EA 575 syrup and drops were considered efficacious and therapeutically equivalent based on assessments of lung functionCitation19. Treatment with EA 575 suppositories or drops also resulted in similar, clinically relevant improvements in FEV1, FVC and RAW in children with bronchial asthma, but no clinically relevant changes or differences were observed in the incidence or intensity of cough and shortness of breathCitation20.

Efficacy of EA 575 in observational studies

The designs of the observational studies are summarized in . Eight of the studies were prospective (typically described as post-marketing surveillance studies)Citation29–31,Citation33–37, and one was a retrospective review of patient filesCitation32. The studies generally considered children with acute and chronic bronchitis, or inflammatory or obstructive respiratory diseases (). The studies were of moderate size (30–200 children), with the exception of two larger prospective studies (>1,000 children) and the retrospective study (>52,000 children – safety outcomes only). Five of the studies also included adults and did not present outcomes separately for different age groupsCitation30,Citation31,Citation33,Citation35,Citation37. The efficacy of EA 575 was evaluated in seven studies by documenting changes in specific patient symptoms (such as cough, expectoration, and shortness of breath) and using patient- and/or clinician-rated global assessments of efficacy.

Table 2. Summary of observational studies of EA 575 in pediatric patients.

Across the observational studies, a high proportion of patients (91%) and clinicians (≥86%) rated the global efficacy of EA 575 as good or very goodCitation30,Citation31,Citation36. Regarding specific aspects of cough, patients treated with EA 575 showed improvements on cough frequency, shortness of breath, expectoration, and respiratory painCitation29–31,Citation33,Citation34,Citation36,Citation37. Furthermore, one of the large studies in >1,000 school children with acute bronchitis documented a 58.1% reduction from baseline in patient- or parent-reported sleep problems after 7 days of EA 575 treatmentCitation36. Overall, the number of episodes of wakefulness decreased from approximately 7 times per night to 2 times per nightCitation36.

Safety and tolerability of EA 575 in pediatric patients

Safety and tolerability data for EA 575 were primarily obtained from the observational studies. Overall, studies documented a low incidence of adverse events (AEs) among pediatric patients who received EA 575Citation29–37. In the large, retrospective review of >52,000 pediatric patient files (15% aged <1 year, equating to >7,000 infants), the incidence of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) was 0.2%Citation32.

The most common AEs affected the gastrointestinal tract (e.g. diarrhea, enteritis, and nausea) but still occurred at a low incidence (<2% of patients)Citation31–33,Citation35,Citation36. When analyzed according to age, the incidence of gastrointestinal ADRs was highest among children <1 year of age (0.35% of >7,000 infants) and decreased with increasing ageCitation32. Dermatological AEs (e.g. allergic exanthema/urticaria) were documented in a minority (typically, ≤0.6%) of patientsCitation30,Citation32–34.

Across all studies (clinical trials and observational), a high proportion of patients (≥95%) and clinicians (≥96%) rated the tolerability of EA 575 as good or very goodCitation20,Citation21,Citation25,Citation29,Citation30,Citation33–37. In one active-controlled trial, all clinicians rated the tolerability of EA 575 as good or very good, whereas 76% of clinicians rated the tolerability of acetylcysteine as good or very goodCitation25. In another active-controlled trial, the mean clinician- and patient-rated global assessment of tolerability was good (scores of 4.2 and 4.0, respectively, out of 5), and comparable between EA 575 and ivy leaf DER 2.2–2.9:1Citation26. Similarly, a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial did not reveal any relevant differences in patient- or clinician-rated tolerability between EA 575 and placeboCitation21.

Expert survey

In total, 322 email invitations to the expert survey were sent out. Thirty healthcare professionals gave consent to participate in the survey, of whom 18 met eligibility criteria, and 14 answered at least one question in the EA 575 section.

Participant characteristics

The 14 participants represented 9 countries: Croatia (n = 3), Germany (n = 2), the United Kingdom (n = 2), the United States (n = 2), Italy (n = 1), Malaysia (n = 1), Qatar (n = 1), Slovenia (n = 1), and the United Arab Emirates (n = 1). All participants had treated pediatric cough for >10 years and had managed >30 pediatric patients with cough in the past 6 months. Regarding the expertise of the healthcare professionals, 13 (93%) spent >50% of their professional time in clinical practice, 12 (86%) had participated in a specialist pediatric cough congress or session within a pediatric respiratory conference, 7 (50%) had been an author on an article relating to pediatric cough published in a peer-reviewed journal, and 8 (57%) had worked on national or international pediatric cough guidelines.

Four of the 14 participants (29%) had not prescribed or recommended EA 575 for pediatric patients and, therefore, were ineligible to continue with the survey. Reasons given for not prescribing or recommending EA 575 were not knowing about the product (n = 3) and a perceived lack of evidence of its efficacy (n = 1).

EA 575 for pediatric cough

In the past 6 months, all ten participants had recommended EA 575 to pediatric patients with acute cough. A small number of participants had also recommended EA 575 for chronic cough (n = 2) or chronic respiratory conditions such as asthma or chronic obstructive bronchitis (n = 2). EA 575 was recommended to children aged <1 year (n = 2), 1–2 years (n = 7), 3–6 years (n = 7), 7–12 years (n = 8), and >12 years (n = 6).

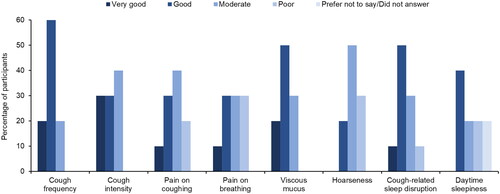

On a 5-point scale from “very good” to “very poor”, participants rated the overall effectiveness of EA 575 for pediatric cough as moderate (n = 1), good (n = 7), or very good (n = 2). Regarding specific symptoms, EA 575 was considered most effective (≥6 participants rated it good or very good) at reducing cough frequency, viscous mucus, cough intensity, and cough-related sleep disruption ().

Figure 1. Clinician-rated effectiveness of EA 575 on reducing symptoms in pediatric patients with cough (n = 10).

Effectiveness was rated on a 5-point scale: very good, good, moderate, poor, or very poor. No clinicians rated the effectiveness of EA 575 as very poor at reducing symptoms.

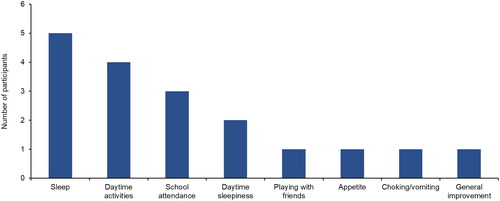

Most participants (n = 8) were of the opinion that EA 575 improved overall quality of life in pediatric patients with cough. Five participants mentioned sleep as an aspect of quality of life that improved with EA 575 (). Specific changes in sleep that were reported included longer duration and fewer awakenings.

Figure 2. Clinician-reported aspects of quality of life that improve with EA 575 (n = 8).

This was an open question.

On a 5-point scale, the overall tolerability of EA 575 in pediatric patients was rated as moderate (n = 1), good (n = 2), or very good (n = 7).

Discussion

Whereas previous reviews have addressed the efficacy and tolerability of EA 575 in adults and children combined, and often grouped with inequivalent ivy leaf extractsCitation3,Citation38,Citation39, the present review specifically and comprehensively evaluated the efficacy and tolerability of ivy leaf dry extract EA 575 in the treatment of pediatric patients with acute or chronic cough, via a literature review and an international expert survey. Nineteen published studies were identified – a mixture of controlled clinical trials and observational studies in pediatric patients with respiratory tract infection, bronchitis, bronchial asthma, and inflammatory or obstructive respiratory diseases. Considering this body of evidence, the findings suggest that EA 575 may provide a variety of clinical benefits in pediatric patients with cough, with minimal side effects. The safety data were mostly derived from real-world studies including a retrospective analysis of >52,000 pediatric patient records, of which >7,000 records were for children aged <1 yearCitation32. Given the large sample sizes across the real-world studies, the low incidence of AEs convincingly demonstrates the favorable safety and tolerability profile of EA 575 in pediatric patients. However, while the safety data were derived from large samples, the efficacy data must be interpreted with caution due to lack of replication, low quality of reporting, and small sample sizes.

Considering cough-related symptoms, the observational studies highlighted a broad range of subjective improvements with EA 575 treatment, including cough frequency, the production of viscous mucus, respiratory pain, and disrupted sleepCitation29–31,Citation33,Citation34,Citation36,Citation37, although results from controlled trials were mixedCitation1,Citation20,Citation21,Citation23–25. One of the observational studies documented a more than three-fold reduction in the number of episodes of wakefulness in a large population of children with acute bronchitisCitation36. In the survey, several clinicians highlighted sleep as a key aspect of quality of life that improved with EA 575 – particularly sleep duration and continuity. Cough is known to have a considerable detrimental impact on sleep for children and their parentsCitation40,Citation41 and, therefore, improved sleep could be a welcome, indirect benefit of EA 575.

Controlled trials of EA 575 were generally positive with regard to changes in objective spirometry and body plethysmography parameters indicative of improved lung function. Active-controlled trials consistently reported improved FEV1 in children with acute or chronic respiratory conditions treated with EA 575, with changes favoring EA 575 over acetylcysteineCitation22,Citation24,Citation25. Trials also demonstrated the equivalent efficacy of different formulations of EA 575 (i.e. syrup, drops, and suppositories) based on objective assessment of lung function in asthma and COPDCitation19,Citation20, and minimal differences were observed between EA 575 and other ivy leaf extracts based on subjective severity rating scales in bronchitisCitation1,Citation23,Citation26. Findings from the placebo-controlled trials were less consistent, with one trial documenting a greater reduction in RAW and increase in FEV1 with EA 575 versus placeboCitation21, and the other reporting no notable changes in these parametersCitation28. Although randomized controlled trials are widely considered to provide the strongest evidence for therapeutic effectCitation42, the placebo-controlled trials of EA 575 were small (≤30 patients), which could potentially account for the contrasting observations.

There is increasing recognition of the value provided by studies conducted in real-world clinical practiceCitation43. Such studies can demonstrate the utility of medical interventions in a broader population than clinical trials, which may be more representative of the patients encountered by cliniciansCitation43. In this review, real-world observational studies of EA 575 were generally larger than the clinical trials – most enrolled >100 children and three studies enrolled >1,000 children – providing greater confidence in the results. As expected with real-world data, the studies focused on safety and tolerability, and efficacy was generally assessed using simplistic subjective measures, such as patient- or clinician-rated global assessment of efficacy. Across the studies, these assessments hinted at clinical benefits with EA 575, which were corroborated by responses to the survey. While these findings suggest a favorable opinion of EA 575 efficacy, real-world evidence of efficacy can, generally, only complement evidence from clinical trialsCitation44.

Overall, studies indicated that EA 575 is generally well tolerated by children with acute or chronic cough, and responses to the survey supported this conclusion. Of the side effects reported with EA 575, gastrointestinal symptoms were most common but still occurred at a low incidence (<2% of patients)Citation31–33,Citation35,Citation36. One large study suggested that side effects with EA 575 may be more frequent in younger children (<1 year of age); however, the incidence was still low (0.35% for gastrointestinal ADRs, versus 0.17% in 0–12-year-olds)Citation32. In general, young children represent a vulnerable patient group, and some regulatory authorities, such as the US Food and Drug Administration, discourage the use of over-the-counter cough medicines in children <2 years of age due to safety concernsCitation45. While the recommended age range for EA 575 treatment varies worldwide depending on local regulatory authorities, it is reassuring that this review did not identify any significant safety concerns in the youngest age groups. Indeed, EA 575 has accumulated more than five decades of post-marketing experience across numerous countries, with some regulators authorizing its use in more vulnerable age groups (i.e. children aged <1 year). Together with the findings from observational studies, there is substantial support for the safety and tolerability of EA 575 in pediatric patients of all ages.

Several aspects of this review may limit the ability to make strong conclusions as to the efficacy of EA 575 in pediatric patients with cough. As discussed above, although the controlled clinical trials provided the highest quality evidence in the literature review, they tended to enroll small numbers of patients, and many did not include a placebo group. This is, perhaps, unsurprising considering the challenges associated with conducting controlled clinical trials in pediatric cough, such as the difficulty in recruiting children, the usually self-limiting nature of acute coughCitation46, and the considerable placebo-effect encountered in trials of cough therapiesCitation47. Furthermore, the age of the clinical trials must be mentioned, as half of the controlled trials were >20 years old. Since the 1990s, the field has advanced, with considerable changes in the diagnosis and treatment of pediatric cough. For example, a diagnosis of COPD in childhood – used in one of the controlled trialsCitation19 – is inconsistent with current understanding of the causes and development of COPDCitation48. Although events in early life may increase the risk of developing COPD in adulthoodCitation49, in current clinical practice, children are not diagnosed with COPD or other chronic obstructive respiratory diseases. Preferred diagnoses may include recurrent wheezy bronchitis, protracted bacterial bronchitis, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, and bronchiolitis obliterans.

The review was also limited by the quality of reporting. Many publications omitted key details of study design, and descriptions of the type, duration, and severity of AEs were not always available. Furthermore, clinical trials often differed in terms of the dose and duration of treatment with EA 575, and the endpoints evaluated. None of the trials included objective assessments of cough improvement; validated methods for measuring cough frequency are required for future research in this fieldCitation18, especially for young children who have limited ability to describe their symptoms. While spirometry provided a quantitative assessment of lung function in a number of studies, performing spirometry in young children (aged <5 years) can be challengingCitation50 and, therefore, some trials excluded these children from testing. Consequently, findings relating to the effects of EA 575 on pediatric lung function must be interpreted with caution. Variation in study design has previously been cited as a barrier to evaluating the overall effectiveness of over-the-counter cough medicinesCitation51. Encouragingly, responses to the survey tended to agree with the findings from the literature. However, while expert opinion is valuable, it may not be representative of day-to-day clinical practice and, as purely subjective assessment of treatment effectiveness, it is not a substitute for clinical evidence. Also, interpretation of the survey responses was limited by the low response rate, which may be due to the strict entry criteria used to identify experts in the field of pediatric coughCitation18. Furthermore, the survey coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic, which is a likely contributor to the low response rate, considering that the target audience consisted of respiratory experts.

Conclusions

Overall, the findings of this review suggest that EA 575 has minimal side effects in pediatric patients with cough, as demonstrated by large real-world studies that convincingly show a favorable safety profile in children, including infants aged <1 year. EA 575 may provide clinical benefits in pediatric patients with acute or chronic cough. However, caution is needed when interpreting the efficacy results due to small sample sizes, subjective outcome measures, and a lack of placebo control groups. To provide more robust evidence for the efficacy of EA 575 in pediatric patients with cough, larger controlled clinical trials would be welcomed, though the challenges associated with such research must be acknowledged. Further evaluation of the impact of EA 575 on aspects of quality of life, such as sleep, would also be valuable for clinicians and patients.

Transparency

Author contributions

GS and CV contributed to the design of the study and the interpretation of data. LU and CPW contributed to the design of the study, acquired the data, and contributed to the interpretation of data. All authors participated in the drafting or the critical review of the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Prospan pediatric review Supplementary file 1 2-Feb-23.docx

Download MS Word (49.5 KB)Supplementary file 2.xlsx

Download MS Excel (27.1 KB)Acknowledgements

Editorial support was provided by Cambridge – a Prime Global Agency, funded by Engelhard Arzneimittel GmbH & Co. KG. The authors thank Dr. Jasmine Fokkens and Dr. Christoph Strehl for the conceptualization of the review paper, and the participants for their time completing the questionnaire.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

GS has received honoraria from Dr. Willmar Schwabe GmbH & Co. KG for scientific services. LU and CPW are employees of Cambridge – a Prime Global Agency, which received funding from Engelhard Arzneimittel GmbH & Co. KG for this work. CV has received study, lecture or consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Engelhard Arzneimittel GmbH & Co. KG, Novartis Pharma, and Sanofi Aventis. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Data availability statement

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article and its supplementary files (see Supplementary file 2).

Additional information

Funding

References

- European Medicines Agency (EMA) Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC). Assessment report on Hedera helix L. folium. 2017; EMA/HMPC/325715/2017.

- Prospan® cough syrup. Package leaflet. Germany: Engelhard Arzneimittel GmbH & Co. KG; October 2018.

- Lang C, Röttger-Lüer P, Staiger C. A valuable option for the treatment of respiratory diseases: review on the clinical evidence of the ivy leaves dry extract EA 575®. Planta Med. 2015;81(12–13):968–974. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1545879.

- Reckhenrich AK, Klüting A, Veit M. Ivy leaf extracts for the treatment of respiratory tract diseases accompanied by cough: a systematic review of clinical trials. HerbalGram. 2018;117:58–71.

- Wichtl M (ed). Hederae folium. In: Herbal drugs and phytopharmaceuticals, 3rd ed. Stuttgart: medPharm GmbH Scientific Publishers; 2004. p. 274–277.

- Greunke C, Hage-Hülsmann A, Sorkalla T, et al. A systematic study on the influence of the main ingredients of an ivy leaves dry extract on the β2-adrenergic responsiveness of human airway smooth muscle cells. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2015;31:92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2014.09.002.

- Sieben A, Prenner L, Sorkalla T, et al. α-hederin, but not hederacoside C and hederagenin from Hedera helix, affects the binding behavior, dynamics, and regulation of β2-adrenergic receptors. Biochemistry. 2009;48(15):3477–3482. doi: 10.1021/bi802036b.

- Wolf A, Gosens R, Meurs H, et al. Pre-treatment with α-hederin increases β-adrenoceptor mediated relaxation of airway smooth muscle. Phytomedicine. 2011;18(2–3):214–218. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2010.05.010.

- Meurer F, Schulte-Michels J, Häberlein H, et al. Ivy leaves dry extract EA 575® mediates biased β2-adrenergic receptor signaling. Phytomedicine. 2021;90:153645. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2021.153645.

- Proskocil BJ, Fryer AD. B2-agonist and anticholinergic drugs in the treatment of lung disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2(4):305–310. doi: 10.1513/pats.200504-038SR.

- Anzueto A, Jubran A, Ohar JA, et al. Effects of aerosolized surfactant in patients with stable chronic bronchitis: a prospective randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1997;278(17):1426–1431. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03550170056032.

- Button B, Goodell HP, Atieh E, et al. Roles of mucus adhesion and cohesion in cough clearance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115(49):12501–12506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1811787115.

- Hohlfeld J, Fabel H, Hamm H. The role of pulmonary surfactant in obstructive airways disease. Eur Respir J. 1997;10(2):482–491. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10020482.

- Rubin BK, Ramirez O, King M. Mucus rheology and transport in neonatal respiratory distress syndrome and the effect of surfactant therapy. Chest. 1992;101(4):1080–1085. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.4.1080.

- Schulte-Michels J, Runkel F, Gokorsch S, et al. Ivy leaves dry extract EA 575® decreases LPS-induced IL-6 release from murine macrophages. Pharmazie. 2016;71(3):158–161. doi: 10.1691/ph.2016.5835.

- Schulte-Michels J, Keksel C, Häberlein H, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of ivy leaves dry extract: influence on transcriptional activity of NFκB. Inflammopharmacology. 2019;27(2):339–347. doi: 10.1007/s10787-018-0494-9.

- Völp A, Schmitz J, Bulitta M, et al. Ivy leaves extract EA 575 in the treatment of cough during acute respiratory tract infections: meta-analysis of double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):20041. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-24393-1.

- Vogelberg C, Cuevas Schacht F, Watling CP, et al. Therapeutic principles and unmet needs in the treatment of cough in pediatric patients: review and expert survey. BMC Pediatr. 2023;23(1):34. doi: 10.1186/s12887-022-03814-0.

- Gulyas A, Repges R, Dethlefsen U. Consequent therapy of chronic obstructive respiratory tract illnesses in children. Atemw Lungenkrkh. 1997;5:291–294. [Translated title]

- Mansfeld HJ, Höhre H, Repges R, et al. Sekretolyse und bronchospasmolyse. TW Pädiatrie. 1997;10(3):155–157.

- Mansfeld HJ, Höhre H, Repges R, et al. Therapie des Asthma bronchiale mit Efeublätter-Trockenextrakt. Munch Med Wochenschr. 1998;140(3):26–30.

- Gulyas A. Efeublätter-Extrakt zeigt bei Kindern mit chronisch obstruktiven Atemwegserkrankungen vergleichbare Effekte wie Acetylcystein. 1999; [cited 2023 Feb 1]. Available from: https://phytokompass.de/efeublaetter-extrakt-zeigt-bei-kindern-mit-chronisch-obstruktiven-atemwegserkrankungen-vergleichbare-effekte-wie-acetylcystein/.

- Unkauf M, Friederich M. Bronchitis bei kindern: klinische studie mit Efeublätter-Trockenextrakt. Der Bayerische Internist. 2000;4:1–4.

- Maidannik V, Duka E, Kachalova O, et al. Efficacy of prospan application in children’s diseases of respiratory tract. Pediatr Tocol Gyn. 2003;4:1–7.

- Bolbot Y, Prokhorov E, Mokia S, et al. Comparing the efficacy and safety of high-concentrate (5–7.5:1) ivy leaves extract and acetylcysteine for treatment of children with acute bronchitis. Drugs of Ukraine. 2004;11:1–4. [Translated title]

- Cwientzek U, Ottillinger B, Arenberger P. Acute bronchitis therapy with ivy leaves extracts in a two-arm study. A double-blind, randomised study vs. an other ivy leaves extract. Phytomedicine. 2011;18(13):1105–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2011.06.014.

- EU. Clinical Trials Register (2007-003272-19); [cited 2023 Feb 1]. Available from: https://www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/ctr-search/search?query=2007-003272-19.

- Zeil S, Schwanebeck U, Vogelberg C. Tolerance and effect of an add-on treatment with a cough medicine containing ivy leaves dry extract on lung function in children with bronchial asthma. Phytomedicine. 2014;21(10):1216–1220. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2014.05.006.

- Lässig W, Generlich H, Heydolph F, et al. Wirksamkeit und Verträglichkeit efeuhaltiger Hustenmittel. TW Pädiatrie. 1996;9:489–491.

- Hecker M. Wirksamkeit und Verträglichkeit von Efeuextrakt bei Patienten mit atemwegserkrankungen. Natura Med. 1999;14(2):28–33.

- Hecker M, Runkel F, Völp A. Behandlung chronischer Bronchitis mit einem Spezialextrakt aus Efeublättern – multizentrische Anwendungsbeobachtung mit 1350 patienten. Forsch Komplementärmed Klass Naturheilkd. 2002;9:77–84. doi: 10.1159/000057269.

- Kraft K. Verträglichkeit von Efeublättertrockenextrakt im Kindesalter. Z Phytother. 2004;25:179–181.

- Fazio S, Pouso J, Dolinsky D, et al. Tolerance, safety and efficacy of Hedera helix extract in inflammatory bronchial diseases under clinical practice conditions: a prospective, open, multicentre postmarketing study in 9657 patients. Phytomedicine. 2009;16(1):17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2006.05.003.

- Beden AB, Perko J, Terčelj R, et al. Potek zdravljenja akutne okužbe dihal pri slovenskih otrocih s sirupom, ki vsebuje izvleček listov bršljana. Zdrav Vestn. 2011;80:276–284.

- Stauss-Grabo M, Atiye S, Warnke A, et al. Observational study on the tolerability and safety of film-coated tablets containing ivy extract (Prospan® cough tablets) in the treatment of colds accompanied by coughing. Phytomedicine. 2011;18(6):433–436. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2010.11.009.

- Lang C, Staiger C, Wegener T. Efeu in der pädiatrischen Praxis: Anwendung von EA 575® in der Therapie der akuten Bronchitis bei Schulkindern. Z Phytother. 2015;36(05):192–196. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-105237.

- Kruttschnitt E, Wegener T, Zahner C, et al. Assessment of the efficacy and safety of ivy leaf (Hedera helix) cough syrup compared with acetylcysteine in adults and children with acute bronchitis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2020;2020:1910656. doi: 10.1155/2020/1910656.

- Barnes LAJ, Leach M, Anheyer D, et al. The effects of Hedera helix on viral respiratory infections in humans: a rapid review. Adv Integr Med. 2020;7(4):222–226. doi: 10.1016/j.aimed.2020.07.012.

- Sierocinski E, Holzinger F, Chenot JF. Ivy leaf (Hedera helix) for acute upper respiratory tract infections: an updated systematic review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2021;77(8):1113–1122. doi: 10.1007/s00228-021-03090-4.

- Shields MD, Bush A, Everard ML, et al; British Thoracic Society Cough Guideline Group. BTS guidelines: recommendations for the assessment and management of cough in children. Thorax. 2008;63(Suppl 3):iii1–iii15. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.077370.

- De Blasio F, Dicpinigaitis PV, Rubin BK, et al. An observational study on cough in children: epidemiology, impact on quality of sleep and treatment outcome. Cough. 2012;8(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1745-9974-8-1.

- Burns PB, Rohrich RJ, Chung KC. The levels of evidence and their role in evidence-based medicine. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128(1):305–310. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318219c171.

- Blonde L, Khunti K, Harris SB, et al. Interpretation and impact of real-world clinical data for the practicing clinician. Adv Ther. 2018;35(11):1763–1774. doi: 10.1007/s12325-018-0805-y.

- Roche N, Anzueto A, Bosnic Anticevich S, et al. Respiratory effectiveness group collaborators. The importance of real-life research in respiratory medicine: manifesto of the respiratory effectiveness group. Eur Respir J. 2019;54(3):1901511. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01511-2019.

- US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Should you give kids medicine for coughs and colds? FDA. October 2021; [cited 2023 Feb 1]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/should-you-give-kids-medicine-coughs-and-colds.

- Dicpinigaitis PV. Cough: an unmet clinical need. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;163(1):116–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01198.x.

- Eccles R. The powerful placebo effect in cough: relevance to treatment and clinical trials. Lung. 2020;198(1):13–21. doi: 10.1007/s00408-019-00305-5.

- The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 2023 report; [cited 2023 Feb 2]. Available from: https://goldcopd.org/2023-gold-report-2/#.

- Deolmi M, Decarolis NM, Motta M, et al. Early origins of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: prenatal and early life risk factors. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(3):2294. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20032294.

- Seed L, Wilson D, Coates AL. Children should not be treated like little adults in the PFT lab. Respir Care. 2012;57(1):61–74. doi: 10.4187/respcare.01430.

- Smith SM, Schroeder K, Fahey T. Over-the-counter (OTC) medications for acute cough in children and adults in community settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(11):CD001831. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001831.pub5.