Abstract

Objective

Treatment options for adults with chronic cough (CC) are limited. This study reports on the health status and experiences of patients with recent healthcare evaluation for CC.

Methods

This prospective, UK, cross-sectional study surveyed adults with a CC evaluation within the previous 12 months. All were never smokers (or ex-smokers for ≥12 months). Subjects completed five validated patient-reported outcome measures: cough visual analogue scale (VAS), EuroQoL 5 dimension, 5 level (EQ-5D-5L), EQ-5D VAS, Leicester Cough Questionnaire (LCQ), and Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) questionnaire.

Results

A total of 101 participants were recruited: 71% were female, mean age was 54.9 ± 15.2 years. Median (IQR) CC duration was 36 (11, 120) months. Mean self-reported CC severity (Cough-VAS) was 51.3 ± 22.9 over the previous 2 weeks and 62.9 ± 23.7 on the worst day of coughing. EQ-5D values were lower for CC patients than population norms. Subanalyses revealed that EQ-5D and LCQ scores were significantly impacted by CC duration and the number of healthcare providers (HCPs) visited. WPAI analysis showed a 27.6% work time impairment because of participants’ CC. The number of HCP attendances ranged from 1 to 10 (3.3 ± 2.8) before diagnosis was confirmed. Treatment was being prescribed to 87% of participants and comprised mainly steroids (nasal [19%] and inhaled [25%]), beta agonists (24%), and proton pump inhibitors (21%); 44% of patients were dissatisfied with treatment efficacy.

Conclusion

Real-world data from a nationally representative UK population show significant unmet needs associated with CC, including multiple healthcare visits and limited treatment effectiveness, resulting in inadequate cough control and impaired health status.

Introduction

Chronic cough (CC) is associated with a significant impact on quality of life, affecting patients physically, socially and psychologicallyCitation1–4. Evaluation and management of the condition can be complex and protracted, with a subgroup subsequently diagnosed as having refractory chronic cough (RCC), i.e. cough that persists despite investigations and guideline-based treatment of underlying conditions commonly associated with cough, or unexplained chronic cough (UCC), i.e. clinical assessment fails to identify a cause after evaluation and treatment in line with evidence-based guidelines.

The global prevalence of CC is estimated to be around 10% but is higher in Europe, America and Australia (10–20%) than in Asia and Africa (<5%)Citation5. Populations with RCC or UCC constitute a subset of the overall CC population and experience greater cough burden and report greater impact on quality of lifeCitation6. Prevalence rates for RCC and UCC are harder to determine and most estimates originate from specialist cough clinics. A retrospective analysis of electronic notes from a UK tertiary cough clinic reported that of 276 CC referrals, 59.1% had no identifiable underlying diagnosis or did not respond to treatment trials of identified conditionsCitation7. Data from a CC clinic in the Netherlands, which evaluated nearly 2400 patients, found that 37.5% of the CC patients had RCC and 9.5% UCCCitation8.

Appropriate treatment has been shown to improve health-related quality of life in patients with CCCitation9. However, as the underlying diagnoses remain unknown for many patients, targeted intervention is not always effective or feasible. The resultant impairment of patient quality of life can be associated with both medical and socio-economic consequences. Accurate and responsive outcome measures are necessary to obtain a comprehensive understanding of this impact on patients. Subjective patient-reported outcomes are particularly important to measure aspects of cough that have an impact on the individual, such as cough severity or disruption to working or daily life. Without valid or repeatable cough-specific patient-reported outcome measures, the confidence of research examining treatments for CC will remain uncertain, and the impact on patients unclearCitation10.

The aim of this real-world study was to characterise and detail the experiences, perceptions and challenges of patients with CC who have undergone healthcare evaluation. The impact of CC on quality of life and activities of daily living was assessed using a range of validated patient-reported outcome measures.

Materials and methods

Study population

This prospective, cross-sectional survey of adults aged ≥18 years diagnosed with CC was conducted between February 2020 and February 2022 from a geographically representative spread of different centres/hospitals across the UK. Individuals were recruited with the help of a local recruitment partner via their healthcare professional (HCP) outreach or through a patient recruitment panel (and any subsequent patient referrals). The latter method was adopted during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID19) pandemic when face-to-face healthcare visits were restricted. A summary of the recruitment procedure is provided in Supplementary Figures 1 and 2. Briefly, individuals recruited via their HCP outreach were required to have been experiencing cough on most days of the week for a period of ≥8 weeks despite treatment of the cough or an underlying condition that may be related to their cough. A patient recruitment panel comprises a group of individuals who have voluntarily agreed to participate in healthcare research studies, for example via online registrations or healthcare provider referral. For those recruited via a patient panel a major consideration was the lack of a physician-confirmed diagnosis. Eligibility criteria for patients recruited via a recruitment panel were therefore adapted with input from an external expert in CC. As part of this adaptation, it was determined that exclusion criteria 5 and 6 (Supplementary Figure 1), related to documented evidence of an abnormality through chest X-ray or spirometry, could not be accurately determined by patient self-assessment alone, as these were based on healthcare provider opinion. Consequently, these were replaced with a proxy inclusion criterion 4 (Supplementary Figure 2), which required patients to have been experiencing cough on most days of the week for ≥12 months, to have had ≥1 HCP consultation for their cough in the past 12 months, and to have continued cough despite prescription of a treatment for their cough or a treatment for a condition that may be related to their cough for a period of ≥4 weeks. Recruitment panel patients were first screened online to confirm eligibility, before being validated by the local recruitment partner. This validation process involved sending photographs of their medication(s) or accompanying hospital letters via a secure link. This information was viewed and immediately deleted upon confirmation that the respondent met the requisite screening criteria. Patients meeting the screening criteria were then contacted via the same local recruitment partner to brief them on the study and send them the pen-and-paper questionnaire. When recruited through an HCP outreach, recruitment was targeted through primary care physicians/general practitioners (GPs) as well as through secondary care respiratory specialists and/or tertiary cough clinics.

Eligible patients were required to have either never smoked (cigarettes, marijuana or other tobacco products including e-cigarettes or other vaping devices), or to be an ex-smoker for at least 12 months, and with less than 20 pack years. In addition, patients were required to have had at least one consultation with a physician (either in-person or virtually) about their cough in the last 12 months. Patients with a medical history of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, bronchiectasis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and/or lung cancer, and those with a positive test result for COVID-19 either before or shortly after the onset of their cough, or within the past 3 months, were excluded from completing the survey.

Questionnaire surveys

All participating patients were provided with the relevant pen-and-paper survey materials and instructed to complete the questionnaire independently. The survey took approximately 30 min to complete, after which patients returned the questionnaire to the local recruitment partner either in a sealed envelope or via a scanned e-mail attachment. HCPs were not involved in the completion of the surveys nor were the patient responses made available to them. The exclusion of HCPs in this data collection process helped to ensure that they had no influence over the data input by patients.

All participating patients were assigned a survey number so that the data remained pseudo-anonymised. Each recruiting HCP was also assigned a unique ID code to further preserve the anonymisation process.

The structured questionnaire collected information on demographic and cough characteristics, diagnostic pathway, cough referral pathway, HCP-patient relationships, and cough treatment patterns. A complete list of the variables captured in the survey is shown in .

Table 1. Variables collected.

Cough characteristics were assessed using the cough visual analogue scale (cough VAS), which scores patient-reported cough severity in the last 2 weeks from 0 to 100 (0 = no cough, 100 = worst cough ever), and by questioning patients about their satisfaction with currently prescribed cough treatment.

Current health status was assessed by the EuroQoL 5 dimension, 5 level (EQ-5D-5L) and EQ-5D-VAS [EQ-5D]. The EQ-5D-5L collects patient responses on mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. Patient responses are converted into a continuous summary score that ranges from just less than 0 to 1, where a higher score indicates a better quality of life. The EQ-5D VAS records the patient’s self-rated health on a vertical VAS, where the endpoints are labelled “100 – The best health you can imagine” and “0 – The worst health you can imagine”.

Impact of cough on quality of life was assessed with the Leicester Cough Questionnaire (LCQ)Citation11. The LCQ is a 19-item questionnaire which measures the effect of cough in three domains: psychological, physical and social. It creates four scores: a psychological domain score, physical domain score, social domain score and total score. The total score range is 3–21 and domain scores range from 1 to 7; a higher score indicates a better quality of life.

Impact of cough on daily living and work productivity was assessed with the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Scale (WPAI)Citation12. Over a 7-day recall period, six questions assess the percentage of work time missed because of CC (absenteeism), the percentage of time impaired while at work (presenteeism), total work productivity loss (an overall work impairment estimate that is a combination of absenteeism and presenteeism), and the percentage of impairment in daily activities. With the exception of the last subdomain, which assesses regular day-to-day activities, the WPAI is relevant only for those patients in some form of employment.

Study objectives

The primary objective was to assess the impact of CC on patient-reported outcomes using the EQ-5D-5L, EQ-5D VAS, LCQ, and WPAI. Secondary objectives were to: understand patient experiences with CC; evaluate the impact of CC on patients in terms of symptoms, emotional and socio-economic burden; understand the impact of CC on activities of daily living; and establish patient perceptions and expectations in relation to their disease management within the UK National Health Service (i.e. tests undertaken, referral patterns etc.)

Statistical analysis

Fully de-identified patient reported data from the survey were manually entered and transferred to a single electronic database. Descriptive analyses were then conducted by Adelphi Real World (ARW) in IBM® SPSS® Data Collection Survey Reporter v7.5 software, with any statistical analyses conducted in Stata statistical software version 16.0 or later (StataCorp, 2015. Stata statistical software: Release 16, College Station, TX, StataCorp LP). As this was an exploratory survey and the analyses were primarily descriptive in nature, no formal hypothesis was tested. Numeric variables were summarised by the mean, standard deviation, median, quartiles (1st and 3rd), minimum, maximum and number of non-missing values. Categorical variables were summarised by the total number of non-missing subjects and the number and proportion of subjects in each category. T-test (for comparison of two groups) and ANOVA (for comparison of more than two groups) parametric tests were used to compare outcomes in the subanalyses of individuals with a cough duration ≥12 months vs <12 months, and between those who had seen 1 HCP vs ≥3 HCPs. The null hypothesis assumed the means were equal across groups. Statistical significance was set at a level of p < .05).

Ethics statement

As part of the development of the study protocol, the need for ethics committee review was considered by the core design team, with reference to the Governance Arrangements for Research Ethics Committees: 2018 edition, published by the NHS Health Research Authority, and the accompanying Health Research Authority decision tool (https://hra-decisiontools.org.uk/ethics/). The focus of the project was to describe current practice and care. There was no randomisation to specific treatment approaches or observations; there was no change to the care provided; there was no collection of data by the patient’s healthcare team (new or otherwise); and there was no intent to generate or test a hypothesis or provide new generalizable knowledge. As such the project was considered not to constitute research and so no ethical review committee review or approval was required.

Results

Demographic characteristics

A total of 101 participants diagnosed with CC were recruited: 53 (52.5%) via HCP outreach and 48 (47.5%) via a patient recruitment panel. Respondent demographic characteristics are provided in . The nationwide distribution was as follows: 65% resided in England, 26% in Wales, and 8% in Scotland. The mean age (±SD) was 54.9 (±15.2) years and the majority of the sample were assigned female sex at birth (71%). The majority of respondents (60%) had never smoked and 67% rated their general health, at the time of survey completion, as either fair (35%) or good (32%). A higher education (undergraduate or post-graduate university degree) had been achieved by 37%, around half were currently in employment, either working full time (41%) or part time (11%); just over a quarter (27%) were retired. The proportion unable to work for various health reasons was 12%.

Table 2. Demographic characteristics.

Cough severity

The median (IQR) duration of time that respondents had been experiencing a daily or almost daily cough was 36.0 (11.0, 120.0) months and the mean duration (±SD) was 94.6 (±130.2) months. Mean self-reported cough severity as captured by the Cough-VAS was 51.3 (±22.9) over the previous 2 weeks, and 62.9 (±23.7) on the worst day of coughing over the previous 2 weeks. As a benchmark, a score of <40 on the VAS scale is generally regarded as mild, ≥40–<70 as moderate, ≥70–<90 as severe, and ≥90 as very severeCitation13. Using these bandings, self-reported cough severity was mild in 32 (33.0%) respondents, moderate in 41 (42.3%), severe in 20 (20.6%) and very severe in 2 (2.1%) of respondents (95 evaluable responses). A total of 45% of respondents stated that cough was more severe at a certain time of the year, and among those, 60% reported that it was most severe in the winter months, with a largely equal split across the other three seasons.

Impact of chronic cough on patient reported outcomes

The overall EQ-5D score was 0.7 (). General population norms sourced for the EQ-5D index have reported a benchmark score of 0.9 in the UK overall, and 0.8 for people aged between 55-64 years, the average age of patients in this studyCitation14. Subgroup analyses showed that EQ-5D scores varied with CC duration, with an overall EQ-5D score of 0.8 for patients with a duration <12 months (n = 21) and 0.7 for those with a duration ≥12 months (n = 67). It was also affected by the number of HCP types visited with mean scores of 0.8 (± 0.3) for participants having visited ≤ 2 HCP types for their CC, and 0.6 (± 0.3) for those having visited ≥ 3 HCP types (p = .115).

Table 3. Impact of chronic cough on patient-reported outcomes.

EQ-5D dimension analysis revealed that pain and discomfort was the dimension most affected with 26% of respondents reporting at least moderate levels of pain and discomfort. Analysis of the other dimensions found that 21% of respondents had at least moderate mobility problems, 20% had at least moderate problems performing usual activities (e.g. work, study, housework, family, or leisure), 19% were at least moderately anxious or depressed, and 7% had at least moderate problems with self-care.

The mean EQ-5D VAS score was 68.3. General population norms sourced for the EQ-5D VAS report a benchmark score of 82.8 in the UK overall, and 81.7 for people aged between 55 and 64 yearsCitation15.

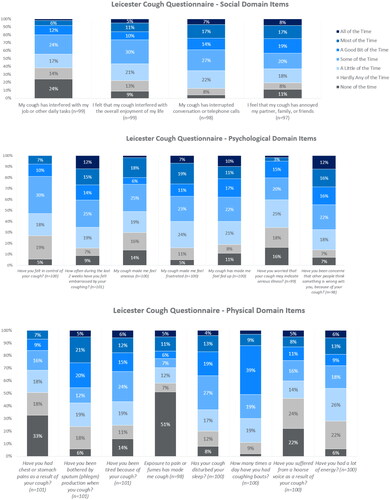

The mean (±SD) total LCQ score was 12.5 (±3.7), with mean scores of 4.4 (±1.3), 4.1 (±1.4), and 4.0 (±1.3) for the physical, social and psychological domains, respectively. Individual LCQ items with the highest reported burden included psychological factors (embarrassment; frustration; feeling fed-up; concerns about what other people think) and social factors (annoying to partner, family, and friends; interrupted conversations; interferes with overall enjoyment of life) (). Items in the physical domain were typically reported as less burdensome compared with the psychological and social domains, although frequent coughing bouts, disturbed sleep, and sputum production were reported as being disruptive at least some of the time by the majority of respondents. Subanalyses again revealed that scores were significantly impacted by the duration of the cough and the number of HCPs visited (Supplementary Table 1).

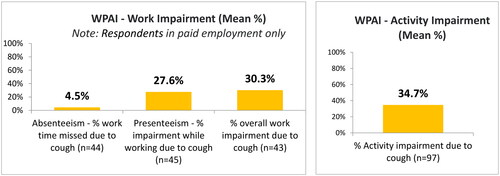

The impact of CC on work productivity and activity was assessed with the WPAI. In the 7 d prior to the survey, the percentage of work time missed because of the participants’ CC was 4.5% (±14.5), and the percentage of impairment experienced because of participants’ CC while at work was 27.6% (±23.6) (). Total work productivity loss due to CC was 30.3% (±24.5). The WPAI also reported an overall activity impairment (daily activity impaired as a result of CC) of 34.7% (±27.8).

Management and treatment experiences of patients with chronic cough

Current and previously prescribed treatments

Antibiotic treatment had been prescribed to half of the patients at some point previously for their CC, making it the most commonly prescribed medication by HCPs. Other common treatments previously received included proton pump inhibitors (34%), nasal or inhaled steroids (32% and 29%) and beta agonists (29%). A high proportion of respondents (71%) reported that they had previously purchased non-prescription (over-the-counter) medication from a pharmacy in an attempt to help to manage their CC. These included treatments such as cough drops/syrups, anti-histamines, and nasal decongestants. In addition, 39% had tried home remedies such as herbal supplements, neti-pots, saline sprays, and Chinese medicine.

Eighty percent of participants reported they were currently being prescribed treatment for CC; 12% were not being prescribed any treatment to help manage their CC at the time of survey completion. Current prescribed treatment was centred around steroids (nasal [19%] and inhaled [26%]), beta agonists (24%), and proton pump inhibitors (21%). Short-term treatments such as antibiotics and oral steroids were much less likely to be prescribed at this stage (both used by 5% of patients).

Of those who were able to provide a response (n = 54), the mean (±SD) duration of time that patients had received their currently prescribed treatment for was 177.3 (±398.6) weeks (3.4 years).

Satisfaction with currently prescribed cough treatment

Fifty-six percent of respondents reported that they were satisfied with their currently prescribed treatment to help manage their CC, and within this subgroup, 39% still believed that better control of their condition was possible, and only 17% believed they were achieving the best possible control. Notably, 44% of respondents were dissatisfied with their current prescribed treatment for CC. Among the respondents dissatisfied with their current prescribed treatment, 45% stated that they had not yet discussed this with their main HCP. A third of patients in the survey (33%) agreed with the statement “I would recommend my treatment to another cough patient,” and over two-thirds (69%) did not believe their treatment was effective at treating their cough symptoms. A similar proportion (70%) wished there was an alternative to their CC medication.

Patient-reported adherence to current prescribed cough treatment

Among respondents currently taking prescribed medication for their cough, 70% self-reported that they rarely (30%) or never (40%) stopped taking their doses without informing their main HCP. A small proportion of responding patients (11%) had completely or regularly reduced or stopped taking doses of their current prescribed cough medications without informing their main HCP.

Among the 30% of patients reporting they did not take their medication as prescribed at least sometimes, the most common reason for lack of adherence was respondents’ not feeling medication was working (45%), followed by not liking the side-effects (32%), feeling they didn’t need to take it as frequently as it was prescribed (32%), and simply forgetting to take it (27%). Patients were also asked to provide the top three most important benefits they would consider in a new treatment for their cough. The most common responses selected were to prevent the worsening of their cough (51%), improve their sleep quality (49%), improve their cough symptoms more quickly (49%), and increase the number of days free from coughing (47%). Reducing other symptoms such as general tiredness and fatigue (33%), as well as stress urinary incontinence (18%), were also fairly common.

Socio-economic burden

A quarter (25%) of patients had considered or made a change to their job situation as a result of their CC. The most common was to actively or seriously consider reducing their hours at work (13–14%), followed by voluntary job termination or consideration of termination (9-10%). Change from full time to part time employment was taken up by 9% of respondents, and early retirement by 8%. A small proportion of patients (4%) had been let go or made to resign from their job due to their cough. Some patients believed that their career prospects were also affected by CC with around a quarter (24%) reporting a strong feeling that it had limited them to certain careers (scoring 5–7 out of 7 where 1 = not at all and 7 = a great deal).

In an average month, respondents reported spending a mean of 1.1 ± 1.2 h travelling to and from appointments related to their CC. While most participants (88%) felt that this was not too long, 15% reported struggling to attend every appointment, regardless of whether or not the journey was deemed too long.

Economic impact of chronic cough

Contribution towards the cost of prescribed CC medication was reported by 28% of participants currently taking such medication. The mean contribution (in £) in the month preceding the survey was £15.2 ± 11.4 with a maximum of £50.0. One in ten patients reported that cost had been a barrier to them taking a prescribed medication for cough in the past.

The majority of patients (71%) had also purchased non-prescription/over-the-counter medications at some time to help treat their cough. Among those who did and reported a figure in the past month, the median spend was £10.0, with a maximum spend of £100.0 on non-prescription treatments.

Perceptions, experiences and expectations in relation to treatment referral pathway

Half the participants (50%) had sought HCP consultation for cough themselves, while 31% were encouraged to do so by family or friends. Where a timeframe was given (n = 71), the median time to first consultation with a doctor or nurse following cough onset was 8 weeks, ranging from 2 to 192 weeks.

Just under half (49%) the respondents reported that they had not yet been informed or diagnosed with a condition as the reason for their cough. Those that had (n = 39) saw a median of 2.0 (range: 1–10) HCPs before they had been informed of this.

Around half (52%) of the respondents reported that they had experienced a long delay in receiving an explanation for their cough following their initial HCP visit. Common reasons for this delay were described as: GP advising them to monitor their symptoms to see if they improved (52%), having to wait to be referred to a specialist (52%) or for additional tests to be conducted (46%).

At the time of survey completion, 22% of participants reported that they were currently waiting for an appointment with a chest or lung specialist (secondary care), while 6% were waiting for a referral to a specialist cough clinic (tertiary care).

Almost all participants (97%) had at some time seen a GP in relation to their CC; 40% had seen a lung specialist, 33% a nurse, and 32% an Ear, Nose and Throat specialist. When asked who was the main person responsible for their cough management, most were managed by their GP (55%) or lung specialist (25%).

As part of their CC evaluation, 69% of participants reported they had undergone chest imaging (CT scan/X-ray), 65% had undergone breathing tests (lung function/spirometry), 30% allergy testing, 21% gastrointestinal examination (endoscopy, barium swallow, pH testing), 18% bronchoscopy, and 9% sinus imaging; 14% had undergone none of the above. Subjects in the latter subgroup were typically younger with a shorter median duration of cough, but mean cough severity was consistent with the overall study population.

Two thirds of patients (67%) were at least somewhat satisfied with their main HCP for CC: 65% were at least somewhat satisfied with communication about CC and its treatment, 64% with understanding and support of treatment goals, 60% with HCP knowledge and understanding of CC, 57% with management and treatment of their CC, and 55% believed their HCP considered their needs when designing treatment goals. Further questioning revealed 62% reported their main cough HCP always had time during consultations to discuss symptoms and other problems, 60% reported there was time for the HCP to explain potential side effects before prescribing a new treatment and 58% that their HCP understood the impact CC was having on their life. However, only just over half (53%) were confident that they were currently receiving appropriate care for their cough, and only 44% that they were kept informed of new treatment options. A lack of treatment success in the past had stopped 17% of participants from seeking further medical attention.

Discussion

In this study of UK participants who had undergone healthcare evaluation for CC, we report clinical and demographic characteristics similar to patients with RCC and UCC recruited to clinical trialsCitation16,Citation17, with evidence of high healthcare utilisation, poor cough control and impaired health status

To gain a better understanding of the cough characteristics, burden and extent of health status impairment in patients with CC, we administered a range of validated patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures. Previous studies have shown that CC is associated with significantly impaired health-related quality of life even when adjusted for clinical confounding factors, such as age, depression, asthma, and COPDCitation18. All the PRO measures used in this study (EQ-5D utility index, EQ-5D-VAS, LCQ, and WPAI) reported scores lower than UK general population benchmarks. For EQ-5D and LCQ, sub-analyses revealed that a cough duration of ≥12 months (vs <12 months) and referral to ≥3 HCP types (vs 1–2 HCPS) were associated with a significantly greater burden on patient quality of life.

CC is associated with impairment across physical, social, and psychological domains, which is generally captured using the LCQ. While EQ-5D dimension analysis revealed that participants were most affected by pain and discomfort with a quarter reporting at least moderate levels, approximately one in five also reported at least moderate mobility problems, moderate difficulties in performing usual activities, and moderate levels of anxiety and depression. Previous research has shown that patients with RCC report a significantly greater burden as measured by the LCQ total score compared with non-RCC patientsCitation6.

The WPAI scores in the present study indicate that most of the employed participants still attended work, but their CC had severely impacted work productivity and activity. Levels of presenteeism (27.6%) and impairment of total work productivity (30.3%) were similar to those reported in recent Asian population-based cross-sectional studies in patients with CCCitation6,Citation19. Participants with CC reported a significantly higher impairment of work productivity compared with matched non-cough respondentsCitation6,Citation19. Overall activity impairment (daily activity impaired as a result of CC) was also high (34.7%) indicating that CC has a significant impact on patients’ work as well as daily life, in agreement with previous studiesCitation6,Citation19–21. Further questioning revealed that a quarter of patients had considered making or made a change to their job situation as a result of their CC such as a reduction in the number of hours, and early retirement. Some patients reported that their condition had limited their choice of careers.

Most patients were managed primarily by their GP or a lung specialist. In line with the latest European Respiratory Society guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of CCCitation22, evaluation was based on a combination approach of selected diagnostic testing and empirical trials of treatment. The most common tests performed were for potential comorbid conditions associated with cough (e.g. chest imaging, lung function, spirometry, allergy testing, gastrointestinal examination). Participants who had received a diagnosis had seen an average of 3.3 HCPs, with long delays reported before confirmation of a cause for their cough. In addition, almost half had not yet received a definitive diagnosis.

Currently there are limited treatment options for patients with CC. Almost 90% of participants reported currently receiving prescribed treatment for CC, most commonly inhaled or nasal steroids, beta agonists and proton pump inhibitors. The mean duration of treatment was 3.4 years. Although a high rate of medication adherence was reported, 44% were dissatisfied with their current treatment, and a lack of treatment success had previously stopped 17% from seeking further medical attention. Perhaps to compensate for the lack of success with prescribed treatments, the majority of patients had at some time purchased over-the-counter medications to relieve their cough symptoms.

Consistent with previous studies, participants in this observational study were predominantly middle-aged, female, never smokersCitation3,Citation4,Citation23,Citation24. Although gender-specific analyses were not performed, previous research has shown a greater impact of CC in women compared with menCitation18,Citation25. It has been suggested that poorer cough-related quality of life may be a result of heightened cough sensitivity in older women and account for the older female predominance commonly found in specialist cough clinicsCitation18,Citation25. The patient clinical and cough characteristics (severity, impact on quality of life) in this study were similar to those described in previous surveysCitation3,Citation4. Characteristics were also similar to those of patients in recent trials of gefapixant, a novel treatment for CCCitation17,Citation23,Citation26, raising the possibility that treatments shown to be effective in clinical trials may also be extended to sufferers of CC in the general population. There remains an unmet need for pharmacological therapies with acceptable therapeutic ratios to manage patients with chronic refractory or unexplained coughs. Evaluation of true drug effect is complicated, however, by the high placebo response seen in cough trialsCitation27. The mechanism of the placebo response is likely to be multifactorial. Participants’ previous experiences and memories and their expectations of receiving effective therapy may all contributeCitation28. It may also be partially attributable to unknown or untreated comorbiditiesCitation27. Non-pharmacological interventions such as cough suppression therapy, education, breathing techniques, mindfulness, suggestion therapy, and continuous positive airway pressure have been shown to minimise the impact of excessive or intense coughing in some studies, but the quality of the evidence has to date proven insufficient for clinical recommendationsCitation29. Further research on the pathophysiological mechanisms involved in RCC and UCC should continue to better define which patients may benefit from pharmacological or non-pharmacological therapy, or a combination of the two, the optimal duration or number of sessions required, and the long-term benefits.

This survey confirms that CC is associated with a significant, and often long-standing patient burden, with high rates of medical consultation and prescribing. Participants were mostly appreciative of their HCPs and understanding of delays in diagnosis, but a high proportion were not satisfied with their current treatments indicating that CC is sub-optimally managed. The fact that the main HCP was their GP, highlights the importance of primary care education on the etiology and diagnosis of CC.

Strengths and limitations

This study collected data from primary care, secondary care respiratory specialists and/or tertiary cough clinics. Efforts were also made to recruit a geographical spread of different hospitals and regions to help minimise bias resulting from a single mode of recruitment (i.e. via specific types of physicians) and to provide data that are applicable nationwide. Additionally, this approach allowed for a more representative sample of CC patients, range of disease durations and types of care. A range of validated PRO measures were used which enabled patients to communicate their experiences, assess whether their experience aligned with their expectations of treatment, and highlight any unmet needs or care areas in need of improvement.

This survey has several limitations. First, the observational nature of this cross-sectional study limits causal inference between CC and quality of life impairment. Second, while we consider the demographic and clinical characteristics of this cohort to be consistent with RCC and UCC, evidence of chest imaging was absent in 31% of the survey population. The use of an internet panel to recruit some participants was necessary to recruit sufficient individuals during the COVID19 pandemic. At this time there may have been greater stigma associated with cough, although respondents were not recruited during periods of high transmission and infection rates. The use of an internet panel may have led to selection bias and a sample unrepresentative of the general population, although the clinical phenotype was consistent with previous studies of CC. All data were self-reported, which may have introduced an amount of patient recall bias, particularly for details on prior investigations and past prescriptions for which patients may not have been able to accurately recall the names of medication classes prescribed.

Conclusions

CC is associated with social, psychological, and physical burden that impacts patients’ daily activities. Challenges faced by patients with CC include numerous consultations, lengthy time to diagnosis, lack of targeted medication, and poor cough control despite trials of treatment.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

The research for this manuscript was funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme (UK) Limited, London, UK.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

MS and GH are employees of Adelphi Real World, which received payment from Merck Sharp & Dohme (UK) Limited, London, UK as part of this research. HL is an employee of Merck Sharp & Dohme (UK) Limited, London, UK. LPM reports receiving consultancy fees from Applied Clinical Intelligence, Bayer, Bellus Health, Bionorica, Chiesi, Merck & Co., Inc., Nocion Therapeutics, and Shionogi; receiving an investigator-initiated grant from Merck & Co., Inc. and Bellus Health; participating on advisory board for AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bellus Health, Chiesi, Merck & Co., Inc., Nocion Therapeutics, Shionogi, and Trevi; and serving as Co-Chair of ERS NEuroCOUGH Clinical Research Consortium.

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

McGarvey_supplementary.docx

Download MS Word (254.8 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Rachael Meadows at Adelphi Real World for her support in conducting the statistical analyses. The services of Gillian Kenny Associates (GKA), Cheltenham, UK, the local recruitment partner, are also acknowledged.

References

- Kuzniar TJ, Morgenthaler TI, Afessa B, et al. Chronic cough from the patient’s perspective. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82(1):56–60. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)60967-1.

- Young EC, Smith JA. Quality of life in patients with chronic cough. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2010;4(1):49–55. doi: 10.1177/1753465809358249.

- Morice AH, Jakes AD, Faruqi S, et al. A worldwide survey of chronic cough: a manifestation of enhanced somatosensory response. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(5):1149–1155. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00217813.

- Chamberlain SAF, Garrod R, Douiri A, et al. The impact of chronic cough: a cross-sectional european survey. Lung. 2015;193(3):401–408. doi: 10.1007/s00408-015-9701-2.

- Song WJ, Chang YS, Faruqi S, et al. The global epidemiology of chronic cough in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2015;45(5):1479–1481. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00218714.

- Kubo T, Tobe K, Okuyama K, et al. Disease burden and quality of life of patients with chronic cough in Japan: a population-based cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2021;8(1):e000764. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2020-000764.

- Al-Sheklly B, Satia I, Badri H, et al. P5 prevalence of refractory chronic cough in a tertiary cough clinic. Thorax. 2018;73:A98.

- Van den Berg JWK, Baxter CA, Edens M, et al. Definition, characteristics and quality of life of patients with chronic cough from the isala chronic cough clinic in The Netherlands. Eur Respir J. 2021;58(Suppl 65):PA1953. doi: 10.1183/13993003.congress-2021.PA1953.

- Takeda N, Takemura M, Kanemitsu Y, et al. Effect of anti-reflux treatment on gastroesophageal reflux-associated chronic cough: implications of neurogenic and neutrophilic inflammation. J Asthma. 2020;57(11):1202–1210. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2019.1641204.

- Boulet LP, Coeytaux RR, McCrory DC, et al. Tools for assessing outcomes in studies of chronic cough: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2015;147(3):804–814. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-2506.

- Birring SS, Prudon B, Carr AJ, et al. Development of a symptom specific health status measure for patients with chronic cough: leicester cough questionnaire (LCQ). Thorax. 2003;58(4):339–343. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.4.339.

- Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4(5):353–365. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199304050-00006.

- Cho PSP, Rhatigan K, Fletcher HV, et al. Defining health states with visual analogue scale and leicester cough questionnaire in chronic cough. Eur Resp J. 2021;58:PA3144. doi: 10.1183/13993003.

- Kind P, Hardman G, Macran S. UK population norms for EQ-5D. https://www.york.ac.uk/che/pdf/DP172.pdf.

- Janssen B, Szende A. Population norms for the EQ-5D. In: szende A, Janssen B, Cabases J, eds. Self-Reported population health: an international perspective based on EQ-5D. Dordrecht (NL): Springer; 2013. p. 19–30.

- Smith JA, Kitt MM, Morice AH, et al. Gefapixant, a P2X3 receptor antagonist, for the treatment of refractory or unexplained chronic cough: a randomised, double-blind, controlled, parallel-group, phase 2b trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(8):775–785. (doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30471-0.

- McGarvey LP, Birring SS, Morice AH, et al. Efficacy and safety of gefapixant, a P2X3 receptor antagonist, in refractory chronic cough and unexplained chronic cough (COUGH-1 and COUGH-2): results from two double-blind, randomised, parallel-group, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2022;399(10328):909–923. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02348-5.

- Won HK, Lee JH, An J, et al. Impact of chronic cough on health-related quality of life in the korean adult general population: the Korean national health and nutrition examination survey 2010-2016. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2020;12(6):964–979. doi: 10.4168/aair.2020.12.6.964.

- Yu CJ, Song WJ, Kang SH. The disease burden and quality of life of chronic cough patients in South Korea and Taiwan. World Allergy Organ J. 2022 ;Sep 515(9):100681. doi: 10.1016/j.waojou.2022.100681.

- Ternesten-Hasséus E, Larsson S, Millqvist E. Symptoms induced by environmental irritants and health-related quality of life in patients with chronic cough – A cross-sectional study. Cough. 2011;7(1):6. doi: 10.1186/1745-9974-7-6.

- Everett CF, Kastelik JA, Thompson RH, et al. Chronic persistent cough in the community: a questionnaire survey. Cough;2007;3:5. doi: 10.1186/1745-9974-3-5.

- Morice AH, Millqvist E, Bieksiene K, et al. ERS guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of chronic cough in adults and children. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(1):1901136. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01136-2019.

- Morice AH, Birring SS, Smith JA, et al. Characterization of patients with refractory or unexplained chronic cough participating in a phase 2 clinical trial of the P2X3-Receptor antagonist gefapixant. Lung. 2021;199(2):121–129. doi: 10.1007/s00408-021-00437-7.

- Zeiger RS, Schatz M, Hong B, et al. Patient-Reported burden of chronic cough in a managed care organization. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(4):1624–1637.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.11.018.

- Cho PSP, Shearer J, Simpson A, et al. Healthcare utilization and costs in chronic cough. Curr Med Res Opin. 2022;38(7):1251–1257. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2022.2065142.

- Dicpinigaitis PV, Birring SS, Blaiss M, et al. Demographic, clinical, and patient-reported outcome data from 2 global, phase 3 trials of chronic cough. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2023;130(1):60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2022.05.003.

- Irwin RS, Madison JM. Gefapixant for refractory or unexplained chronic cough? JAMA. 2023;330(14):1335–1336. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.18508.

- Birring SS, Morice AH, Dicpinigaitis PV, et al. Reply to weinberger. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023;207(12):1650–1651. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202304-0709LE.

- Ilicic AM, Oliveira A, Habash R, et al. Non-pharmacological management of non-productive chronic cough in adults: a systematic review. Front Rehabil Sci. 2022;3:905257.