Abstract

Objective

Limited real-world evidence exists to better understand the patient experience of living with symptoms and impacts of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). This study aimed to (1) describe patient-reported perspectives of NASH symptoms and impacts on patients’ daily lives and (2) develop a patient-centered conceptual NASH model.

Methods

A cross-sectional study using semi-structured qualitative interviews was conducted among adults (≥18 years) in the United States living with NASH. Eligible participants were diagnosed with NASH, had mild to advanced fibrosis (F1-F3), and no other causes of liver disease. The interview guide was informed by a targeted literature review (TLR) to identify clinical signs, symptoms, impacts, and unmet treatment needs of NASH. Participants described their experiences and perspectives around NASH and the symptoms, symptom severity/bother, and impact of NASH on their daily activities. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim for coding and thematic analysis.

Results

Twenty participants (age: 42.4 years; female: 50.0%) were interviewed. Participants discussed their experience with NASH symptoms (most frequent: fatigue [75.0%]; weakness/lethargy [70.0%]) and impacts (most frequent: physical and psychological/emotional [70.0% each]; dietary [68.4%]). Participants considered most symptoms to be moderately severe or severe and moderately or highly bothersome. Findings from the TLR and qualitative interviews were incorporated into a conceptual model that describes patient-reported symptoms and impacts of NASH, clinical signs, risk factors, and unmet treatment needs.

Conclusion

Our study provides insights into patients’ perspectives of NASH symptoms and their impact on their daily lives. These findings may guide patient-physician conversations, supporting patient-centered treatment decisions and disease management.

KEY POINTS FOR DECISION MAKERS

Study findings help to address the gap in current literature about patients’ perspectives on NASH and its symptoms as well as its impact on daily life.

The study proposes a holistic conceptual model that describes patients’ perspectives of living with NASH, including symptoms and their impact, the clinical signs and risk factors of NASH, and the unmet treatment needs of the disease.

Healthcare providers can use study findings to inform patient-focused decisions around treatment strategies for NASH.

1. Introduction

Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is a chronic and progressive form of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)Citation1. NASH is characterized by steatosis (fatty liver) and inflammation with hepatocyte injury (ballooning), with or without fibrosis, and develops in the absence of significant alcohol consumptionCitation1–5. The most common risk factors associated with NASH are obesity, insulin resistance, and features of metabolic syndromeCitation4,Citation6,Citation7. In advanced stages, adults living with NASH have an increased risk of developing liver cirrhosis, liver failure, and hepatocellular carcinomaCitation6.

NASH is strongly associated with several metabolic comorbidities such as obesity and diabetesCitation8, with a high prevalence of obesity (81.8%), diabetes (43.6%), hyperlipidemia (72.1%), hypertension (68.0%), and metabolic syndrome (70.7%) among people with NASHCitation4. Furthermore, the prevalence of NASH is increasing in parallel to the rising prevalence of obesity and type 2 diabetes (T2D), with over 37% of people living with T2D also living with NASHCitation1,Citation4–6,Citation9,Citation10. An estimated 22.5% of people with T2D in the United States (US) have high-risk NASH (i.e. at risk of progression to cirrhosis)Citation11. Obtaining an accurate estimation of the prevalence of NASH is complicated because the diagnosis requires a liver biopsy, which is not performed routinely for all patients with NAFLD, leading to the underdiagnosis of NASHCitation5,Citation12. Furthermore, studies evaluating NASH prevalence are often limited to tertiary hospital populationsCitation7,Citation13. To date, no US Food and Drug Administration-approved pharmacological therapies are available for the treatment of NASH, and patients are advised to make lifestyle modifications through diet and exercise to promote weight lossCitation6,Citation14. Therefore, unmet clinical needs remain in the treatment of NASHCitation5,Citation15.

The current understanding of the patient experience and perspectives regarding NASH symptoms (i.e. physical manifestations of illness) is limited, likely because most patients with NASH do not develop symptoms in the early stages of the disease or they develop ambiguous/generic symptoms like fatigue and abdominal painCitation5. Furthermore, the generic symptoms and clinical signs of the disease overlap with those of other metabolic comorbidities such as T2D, and hence NASH is often considered to be a clinically “silent” diseaseCitation15.

Real-world evidence suggests that people living with NASH perceive a lack of knowledge and clarity about their condition and have limited social supportCitation16. NASH symptoms can have considerable physical and psychological impacts on a patient’s health-related quality of life, affecting their diet, sleep, and work, as well as family life and social activitiesCitation16–23. While previous studies have explored different aspects of patients’ experiences with NASH, such as the symptom burden and impact of living with NASHCitation16,Citation19–23, gaps remain in understanding patients’ perspectives on the overall humanistic burden of NASH and its impact on their daily activities.

The current study aimed to (1) describe patient-reported experiences and perspectives around NASH symptoms and disease impact on patients’ daily lives, and (2) develop a patient-centered conceptual model by conducting a targeted literature review (TLR) and qualitative concept elicitation interviews among adults living with NASH.

2. Methods

2.1. Concept elicitation interviews

2.1.1. Study design and participants

This non-interventional, cross-sectional study gathered insights from participants living with NASH through semi-structured qualitative concept elicitation interviews. Purposive sampling was used to identify and recruit participants from three clinical sites across the US (West, South, and Northeast geographic regions). After potential participants were identified through clinical charts and databases, they were contacted by clinical site staff to undergo screening and determine their eligibility to participate. Adults (aged ≥18 years) with a clinically confirmed or suspected NASH diagnosis were eligible for study participation. Individuals were excluded if they had liver disease from causes other than NASH. presents the complete list of study inclusion and exclusion criteria. Participants received compensation for their participation in the study.

Table 1. Study inclusion and exclusion criteria.

All recruitment procedures complied with US patient confidentiality requirements, including the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 regulations. The study protocol, informed consent form, and individual clinical sites were each approved by a centralized institutional review board (Ethical and Independent Review Services – E&I 20169-01) before this research was conducted. This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.1.2. Procedures and data collection

Participants were invited to complete a one-on-one concept elicitation interview between December 2020 and August 2021. Participants could choose to be interviewed via telephone or a web-based video conference call. Before the scheduled interview, participants received a study packet by mail that contained an informed consent form and a brief sociodemographic questionnaire. Participants provided their written informed consent before starting the interview.

The interviews were conducted by trained research staff experienced in qualitative interviewing, including the authors of this article (RW: PhD; NT: MPH). Interviewers used a semi-structured interview guide to collect qualitative (open-ended questions) and quantitative (rating and ranking questions) data. The development of the interview guide was informed by findings from a TLR conducted to identify key concepts, including clinical signs, symptoms, impact, and unmet treatment needs among adults living with NASH. The interview guide was designed to capture insights into participants’ experiences and perspectives around living with NASH. Participants were asked to describe their condition, their current NASH symptom experience, and the impact of NASH symptoms on their daily life (including physical, functional, emotional/psychological, social/relationship, dietary, and economic impacts). For each NASH symptom, participants described their experiences, the severity of the symptom, and the level of symptom bother. Participants were asked to rate their symptom severity on a scale of 1 to 10 (1 = not severe; 10 = extremely severe) and symptom bother (1 = not bothered; 10 = extremely bothered). In addition, participants ranked their top three most bothersome symptoms. Next, participants were asked to describe how NASH-related symptoms had impacted their daily lives and to rank their top three most bothersome impacts. When time permitted, participants were queried about their NASH symptoms and associated impacts that they may not have spontaneously described during the interview. At the end of the interview, participants completed the sociodemographic questionnaire. All interviews were audio-recorded with participant’s permission.

2.1.3. Sample size

A saturation analysis was conducted to determine the sample size required for the study. Saturation was the point at which participants did not provide any new or previously unidentified concepts during the interviewsCitation24. A saturation grid was used to establish and document concept saturation on the basis of spontaneously mentioned symptoms/impactsCitation24. The saturation grid was used to compare and identify new information, as well as to detect when no new information emerged. Concept saturation was evaluated in an ongoing manner, and interviews were stopped once concept saturation was achieved. To assess concept saturation, participant responses were coded and analyzed to compare the number of new concepts that arose in each subsequent participant interview.

2.1.4. Data analyses

Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim by a professional third-party transcription service, with all personally identifiable information removed from the transcripts. ATLAS.ti (Version 8) was used to code and analyze the transcripts according to an initial coding dictionary. The coding dictionary was developed a priori based on the interview guide. Two experienced coders independently coded one transcript and compared and reconciled the application of codes. Following reconciliation, the coding dictionary was updated as needed to capture emerging themes or streamline the coding process before coding the remaining transcripts. An output consisting of participant quotes organized by thematic code and the number of times each code was applied was produced. A final quality check was performed once coding was completed to ensure accuracy.

Qualitative results were synthesized and summarized descriptively using illustrative quotes, along with participant descriptors: gender (female, male, or non-binary), age, and fibrosis stage (F1, F2, or F3). NASH symptoms were classified as key (i.e. those identified from the TLR) or frequently endorsed (i.e. symptoms reported by five or more participants). Quantitative analysis was conducted on participants’ sociodemographic data and ranking/rating responses. Continuous variables (e.g. age and ranking/rating responses) were described using means, standard deviations (SDs), and ranges. Categorical variables (e.g. gender, ethnicity, and clinical characteristics) were presented using frequencies and percentages.

2.2. NASH conceptual model development

A conceptual model for NASH was developed in a multi-step process. First, a preliminary model was developed based on the findings of the TLR. The preliminary model included more frequently mentioned symptoms and impacts in the literature (i.e. five or more times). Following the analysis of the concept elicitation interviews, the conceptual model was updated to incorporate concepts from both the TLR and the interviews. Finally, concepts identified from analyses of social media conversations using an artificial intelligence-based listening tool were also incorporated into the final conceptual modelCitation25.

3. Results

3.1. Concept elicitation interviews

3.1.1. Participant characteristics

A total of 20 participants were recruited and completed a telephone or virtual (web-based) interview. summarizes the participants’ sociodemographic and clinical characteristics: mean (SD) age: 42.4 (15.6) years; female: 50.0%; White: 75.0%; non-Hispanic/Latino: 55.0%; mean (SD) body mass index (BMI): 36.4 (6.5) kg/m2. Participants were primarily in fibrosis stage F2 (45.0%) or F3 (40.0%) and 55.0% of participants had a NASH diagnosis confirmed by FibroScan. Overall, 55.0% of the participants had T2D and/or hypertension each, while 50.0% had dyslipidemia ().

Table 2. Participants’ sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

3.1.2. NASH symptoms

3.1.2.1. Overall experience of living with NASH and its symptoms

When asked to describe their condition, participants most frequently used the terms “fatty liver disease” and “NASH” (Supplementary Figure 1). When asked about their experience of living with NASH, participants reported disease burden associated with the symptoms including fatigue, pain, sweatiness, nausea/vomiting, headache, and swelling.

presents the symptoms endorsed by participants with illustrative quotes. The key NASH symptoms (both spontaneous and probed) were: being fatigued/tired (n = 15/20; 75.0%), experiencing weakness/lethargy/decreased energy level (n = 14/20; 70.0%), and feeling bloated/swollen (n = 13/20; 65.0%; ). The most frequently endorsed signs and symptoms (i.e. reported by five or more participants) were: being overweight (n = 14/19; 73.7%), abdominal discomfort (n = 13/19; 68.4%), and general discomfort (n = 10/18; 55.6%; ).

Table 3. Summary of key and frequently endorsed NASH symptoms with example quotes from study participants.

Regarding fatigue and lethargy, participants described feeling tired or exhausted without doing anything, even feeling demotivated for activities that they previously enjoyed and having difficulty managing tasks or responsibilities at home or work (). Participants also reported feeling pain and discomfort due to bloating or swelling. Some of the responses were:

Just without energy. I don’t necessarily have to be functioning, like doing something to feel tired. I can just basically feel tired without doing anything.

For me it just feels like when I wake up for the day, I’ve got a lot less energy to do things in my day before I have to just sit around and do nothing.

All the bloated or swollen feeling, it feels like somebody’s put… air hose to my stomach and just let it fill my stomach up. It really is an uncomfortable feeling.

I’ve gained a lot of weight from having NASH because I’m not able to go out and exercise. And it’s hard for me to eat so I’ve gained a lot of weight because my body is kind of in starvation mode.

Abdominal discomfort, I usually feel that when I come in to see the doctor and she examines my abdomen or she palpates it… then I would feel discomfort.

3.1.2.2. Severity of NASH symptoms

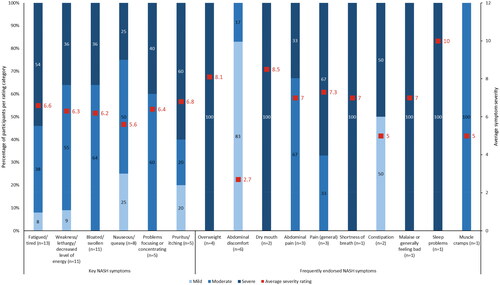

When asked to rank their symptom severity on a scale of 1 to 10 (1 = not severe; 10 = extremely severe), participants rated most symptoms as moderately severe (4 to 6) or severe (7 to 10; ). Participants noted that severe fatigue or tiredness made them feel like they had not slept or they could not function without laying down first (Supplementary Table 1). Those who experienced severe weakness, lethargy, or decreased energy found it “debilitating”. In general, participants described severe bloating or feeling swollen as uncomfortable and irritating but did not find it debilitating or intense. Similarly, nausea or queasiness was generally manageable. Problems with focusing or concentrating were most severe when they interfered with participants’ focus at work and in social settings. Pruritus or itching was mildly severe or severe to the point of bleeding, while abdominal discomfort and general pain were considered to be moderately severe. Being overweight was perceived as mild or severe, and it impacted participants’ ability to do activities that they could do previously (e.g. running; Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1. Average severity ratings for key and frequently endorsed NASH symptoms. n number of participants, NASH non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Note: Key symptoms refer to those identified from the targeted literature review; frequently endorsed symptoms refer to those reported by five or more participants. Participants were asked to rank symptom severity on a scale of 1 to 10 (1 = not severe; 10 = extremely severe).

3.1.2.3. NASH symptom bother

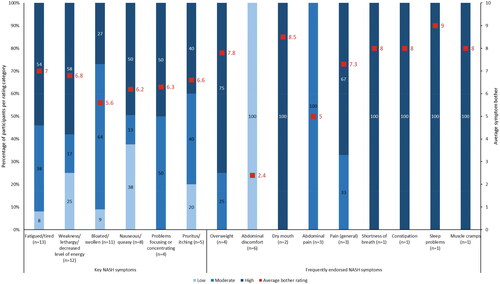

When asked to rate their symptom bother on a scale of 1 to 10 (1 = not bothered; 10 = extremely bothered), participants rated most symptoms between moderately bothersome (4 to 6) and highly bothersome (7 to 10; ). Participants reported being bothered by fatigue and lethargy when the symptoms interfered with their daily activities (Supplementary Table 1). Perceptions of being bloated or swollen varied, with participants reporting either being bothered by it or getting accustomed to it when it did not impact their daily life. Nausea or queasiness was considered to be severely bothersome, while pruritus/itching was considered to be moderately bothersome. Participants were bothered by being overweight, elaborating that they disliked looking at pictures of themselves (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 2. Average bother ratings for key and frequently endorsed NASH symptoms. n number of participants, NASH non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Note: Key symptoms refer to those identified from the targeted literature review; frequently endorsed symptoms refer to those reported by five or more participants. Bother rating categories were low (1-3), moderate (4-6), or high (7-10).

After the interviewers confirmed they had a complete picture of NASH symptoms, they asked the participants to choose their three most bothersome symptoms. Feeling fatigued or tired (n = 11/15; 73.3%), nauseous or queasy (n = 5/8; 62.5%), and abdominal discomfort and feeling bloated/swollen (n = 5/13; 38.5% each) were considered to be the most bothersome NASH symptoms ().

Table 4. Topmost bothersome NASH symptoms and impacts.

3.1.3. Impact of NASH on participants’ daily lives

When asked to describe how NASH had impacted their daily lives, participants most frequently endorsed physical and psychological/emotional (n = 14/20; 70.0% each), dietary (n = 13/19; 68.4%), and daily activity (n = 13/20; 65.0%; ) impacts. Participants discussed the physical impact of NASH in terms of their vitality and not having the energy to do household chores or an inability to exercise. For example:

Table 5. Summary of the impact of NASH with example quotes from study participants.

I would say most of the day I feel tired. I don’t have the energy to do anything, so I can’t really do house chores after work.

I cannot do exercise…And walk and exercise, this exercise bicycle, and I couldn’t do that.

Among those who described the psychological/emotional impact of NASH, participants were concerned that NASH would progress into cirrhosis, or they experienced depression or anxiety due to NASH (). Responses from some participants are as follows:

It worries me…Am I going to advance into full blown cirrhosis? Am I going to have like metabolic or hepatic encephalopathy?

I think maybe probably anxiety…I think that’s probably because of my anxiety because of other things.

I’m trying to eat less. Talking about quantity, less. And avoiding fried food, eating more vegetables.

Just this past year doing anything more active has gotten me tired…doing the vacuum cleaning, running around loading the dishwashers and whatever.

Yes, I don’t have the energy to go out and be social. And then there’s times where I’m so tired and just don’t feel like moving to where I don’t want to see people.

…it does definitely have an economic impact, especially in stuff like insurance and co-pays, because you’re paying…another co-pay, another pharmacy bill, another procedure bill for something else yet again.

Table 6. Participant descriptions of a good and bad day with NASH.

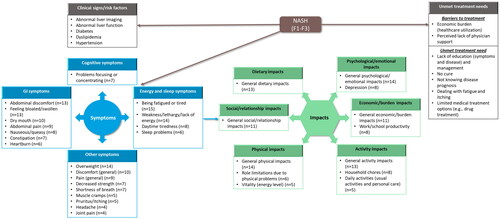

3.2. NASH conceptual model development

Findings from the TLR were used to develop a preliminary conceptual model, which was subsequently updated to include concepts identified during the qualitative interviews to develop a final conceptual model of key concepts and the impact of NASH (). This model includes the concepts identified in the TLR: clinical signs/risk factors (abnormal liver imaging and function, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension); frequently reported symptoms (e.g. fatigue, pain, sleep problems, and discomfort); impacts (e.g. depression, anxiety, work impairment, and social life); and unmet treatment needs (economic burden, lack of education and disease management, absence of a cure, dealing with NASH symptoms such as fatigue and itching, and limited treatment options). In addition, the model incorporates concepts identified using social media analyses (perceived lack of physician support, or lack of knowledge about disease prognosis or treatments)Citation25. Furthermore, the top symptoms (energy/sleep-related symptoms, cognitive, gastrointestinal, and other symptoms) and impacts (physical, emotional, dietary, social, activity, and economic) described by participants during the qualitative interviews are represented in the conceptual model.

Figure 3. Conceptual model of NASH: participants’ perceptions of NASH clinical signs, symptoms, impact, and unmet treatment needs. F fibrosis stage, GI gastrointestinal, n number of participants, NASH non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Note: Concepts listed within grey boxes were identified from the targeted literature review; concepts listed within blue (symptoms) and green (impacts) boxes were identified from both the targeted literature review and qualitative interviews.

4. Discussion

Findings from a TLR and qualitative interviews with 20 participants living with NASH were used to develop a conceptual model of NASH including patients’ perceptions of clinical signs, symptoms, impact, and unmet treatment needs. Through concept elicitation interviews, insights around participants’ perspectives on symptoms and the impact of NASH on their daily lives were elucidated. Participants in this study reported experiencing a variety of NASH symptoms and considered most symptoms to be moderately severe. The results of this study build upon findings from other qualitative studies that assessed patients’ perspectives on NASH/NAFLD symptomsCitation16,Citation19–23. Fatigue and weakness or lethargy were the most frequently reported NASH symptomsCitation16,Citation19,Citation20,Citation22,Citation23, with fatigue affecting patients the most in their daily livesCitation16. A recent qualitative study by Swain et al. reported that NASH patients considered fatigue, abdominal pain, worry, and food restrictions as some of the most important symptoms/impacts of NASHCitation23. Consistent with previous studies, participants in the current study also reported impact of NASH on physical functioning, psychological or emotional aspects, diet, daily activities, relationship or social participation, and economic burdenCitation17,Citation18,Citation20,Citation21. Importantly, the psychological or emotional impacts of NASH were considered to be the most bothersome among participants in the current study.

Due to the lack of approved pharmacological options, physicians recommend lifestyle interventions like weight reduction through diet modification and physical activity as first-line therapy for NASH management based on current treatment guidelinesCitation6,Citation14. Physicians have reported the challenges of conveying the importance of lifestyle modifications to patients with NASH due to inadequate patient education materialsCitation26. On the other hand, patients with NASH may consider this line of treatment to be insufficient or may perceive it as a lack of interest by their healthcare provider in their disease and its managementCitation19,Citation22. Available evidence suggests that even a 5% to 10% reduction in body weight could induce improvements in NASH histologyCitation27. Despite this, many patients are unable to make the required lifestyle modifications. For example, few patients achieve 10% weight reduction in clinical trialsCitation27, possibly due to the lack of adequate support for these patients. Nearly half of the patients with NASH are not referred to diet, nutrition, or exercise specialists who can provide personalized advice to help them make the recommended lifestyle modificationsCitation28. In the present study, several participants were concerned about being overweight and were bothered by the recommended dietary limitations. In addition, participants discussed the challenges of weight reduction, including low motivation, dietary restrictions, and an inability to exercise due to the impact of NASH on their energy levels. Taken together, these findings suggest that understanding patients’ motivational needs, improving patient education, and providing emotional and lifestyle-related support to patients with NASH might help them achieve their weight reduction goals and consequently help in disease managementCitation19,Citation27.

Previous studies have proposed conceptual models on the symptoms, impacts, and barriers and aids to making lifestyle behavioral changes for patients with NASHCitation19,Citation20,Citation23. For example, one conceptual model presented patients’ perceptions of NASH symptoms and their impact as identified during concept elicitation interviewsCitation20. The model characterized the following: (1) key symptoms (pain, fatigue, itching, cognition, sleep impact); (2) risk factors (diabetes and high BMI); (3) psychological risk factors (attitude, motivation, and eating habits); and (4) physical, social, psychological, and economic impacts of NASHCitation20. Another model focused on the aspects that aid (social support, symptoms, and concerns about adverse outcomes) or prevent (impact on quality of life, competing priorities, and time constraints) patients with NAFLD from making lifestyle behavioral changesCitation19. The conceptual model proposed by Swain et al. listed the patient-reported signs and symptoms of NASH (such as fatigue, pain, bloating, and pruritus), immediate impacts resulting from NASH symptoms (decreased physical activity, worry, and frustration), and the general impacts of the condition (such as drowsiness, anxiety, and decreased social functioning)Citation23. The current study proposes a holistic conceptual model that provides comprehensive descriptions of patients’ perspectives of the physical and psychological impact of NASH on their daily lives. This model integrates key concepts such as NASH symptoms (gastrointestinal, energy/sleep-related, and cognitive symptoms) and impacts on patients’ daily activities (physical, emotional, dietary, social, activity, and economic impacts). Furthermore, the model highlights the clinical signs and risk factors of NASH (abnormal liver imaging and function, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension), and unmet treatment needs and treatment barriers (lack of education and absence of a cure). Therefore, this conceptual model provides additional information to what others have previously describedCitation19,Citation20,Citation23. This model may help guide patient-physician conversations around the disease burden and its impact on patients with NASH, enabling a more targeted and personalized approach to NASH disease management.

Strengths and limitations

The key strength of this study is that it utilized concept elicitation interviews to understand the experiences and perspectives of patients living with NASH. The number of participants interviewed reflects the typical sample size for qualitative researchCitation24,Citation29. The study findings address the gap in the literature around understanding patients’ perspectives of the disease symptoms and the resulting impact on their daily lives. We captured the real-world experiences of people living with NASH and other comorbidities, based on how they felt and functioned in their everyday life, as well as the totality of their lived experience with NASH and other comorbidities.

However, the study has its limitations. A majority of participants were White (75.0%). Only patients with mild (F1) to advanced (F3) fibrosis who had not progressed to liver cirrhosis were eligible for the study. Liver cirrhosis is likely to have a deeper physical, emotional, social, functioning and economic impact due to its severe symptomsCitation30; therefore, the perspectives of participants in this study may differ from the experiences of NASH patients with liver cirrhosis. We further acknowledge there may have been several interactions and some overlap in participant experiences based on their different diagnoses, and participants may not have the clinical expertise to attribute their symptoms and impact specifically to NASH as compared to other conditions. That is the reality of the complexity of NASH, which we sought to characterize in the participants’ own words in this study. Finally, the study only included English-speaking US residents. For these reasons, the findings of the present study may not be generalizable to all patients with NASH.

5. Conclusions

This qualitative study identified key symptoms and gaps in the literature around recognizing patients’ experience of living with NASH and its impact on their daily lives. These findings can serve as a foundation for larger studies evaluating the disease burden of NASH. Understanding patients’ perspectives on NASH symptoms and their disease impact could help better characterize and diagnose patients living with NASH. In turn, this would assist healthcare providers in better treatment-related decision-making for their patients living with NASH.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company (Indianapolis, IN, USA).

Declaration of financial/other relationships

SS, CC, and J-LP are employees and stockholders of Eli Lilly and Company. NT is an employee of Evidera. RW is an employee of PRECISIONheor and was an Evidera employee when this research was conducted. Evidera received funding from Lilly to conduct the research that generated the evidence used to develop this manuscript. SMB is currently an employee of IQVIA, and was an employee of Evidera at the time of this research.

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Author contributions

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have read and given their approval for this version to be published. All authors contributed to the conception/design, data analyses and interpretation, manuscript writing, and provided final approval of the manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (46.9 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank Adam Bailey, Fanyang Zeng, Effah Acheampong, Chris Roldan, Hope Paul, and Amira Bakir (Evidera, Bethesda, MD, USA) for assisting with the initial study design, coding/analysis, or report writing. Richa Kapoor, an employee of Eli Lilly Services India Pvt. Ltd., provided medical writing support which was funded by Eli Lilly and Company (Indianapolis, IN, USA).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, SS, upon reasonable request.

References

- Kopec KL, Burns D. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a review of the spectrum of disease, diagnosis, and therapy. Nutr Clin Pract. 2011;26(5):565–576. doi:10.1177/0884533611419668.

- Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, et al. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guidance from the American association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology. 2018;67(1):328–357. doi:10.1002/hep.29367.

- Jean-François D, Roger S, Maria-Magdalena B, et al. The global epidemiology of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and associated risk factors–a targeted literature review. Endocrine Metabolic Sci. 2021;3:100089. doi:10.1016/j.endmts.2021.100089.

- Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, et al. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64(1):73–84. doi:10.1002/hep.28431.

- Sheka AC, Adeyi O, Thompson J, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a review. JAMA. 2020;323(12):1175–1183. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.2298.

- LaBrecque DR, Abbas Z, Anania F, et al. World gastroenterology organisation global guidelines: nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48(6):467–473. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000000116.

- Vernon G, Baranova A, Younossi ZM. Systematic review: the epidemiology and natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34(3):274–285. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04724.x.

- Hamid O, Eltelbany A, Mohammed A, et al. The epidemiology of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) in the United States between 2010-2020: a population-based study. Ann Hepatol. 2022;27(5):100727. doi:10.1016/j.aohep.2022.100727.

- Younossi Z, Anstee QM, Marietti M, et al. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15(1):11–20. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2017.109.

- Younossi ZM, Golabi P, de Avila L, et al. The global epidemiology of NAFLD and NASH in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hepatol. 2019;71(4):793–801. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2019.06.021.

- Vilar-Gomez E, Vuppalanchi R, Mladenovic A, et al. Prevalence of high-risk nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) in the United States: results from NHANES 2017-2018. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21(1):115–124.e7. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2021.12.029.

- Rinella ME, Lominadze Z, Loomba R, et al. Practice patterns in NAFLD and NASH: real life differs from published guidelines. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2016;9(1):4–12. doi:10.1177/1756283X15611581.

- Sherif ZA, Saeed A, Ghavimi S, et al. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and perspectives on US minority populations. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61(5):1214–1225. doi:10.1007/s10620-016-4143-0.

- Cusi K, Isaacs S, Barb D, et al. American association of clinical endocrinology clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in primary care and endocrinology clinical settings: co-sponsored by the American association for the study of liver diseases (AASLD). Endocr Pract. 2022;28(5):528–562. doi:10.1016/j.eprac.2022.03.010.

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) & NASH 2021 [cited 2022 December 5]. Available from: https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/liver-disease/nafld-nash.

- Cook NS, Nagar SH, Jain A, et al. Understanding patient preferences and unmet needs in non-alcoholic ateatohepatitis (NASH): insights from a qualitative online bulletin board study. Adv Ther. 2019;36(2):478–491. doi:10.1007/s12325-018-0856-0.

- Kennedy-Martin T, Bae JP, Paczkowski R, et al. Health-related quality of life burden of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a robust pragmatic literature review. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2017;2(1):28. doi:10.1186/s41687-018-0052-7.

- Geier A, Rinella ME, Balp MM, et al. Real-world burden of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19(5):1020–1029.e7. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2020.06.064.

- Tincopa MA, Wong J, Fetters M, et al. Patient disease knowledge, attitudes and behaviours related to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a qualitative study. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2021;8(1):e000634. doi:10.1136/bmjgast-2021-000634.

- Doward LC, Balp MM, Twiss J, et al. Development of a patient-reported outcome measure for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH-CHECK): results of a qualitative study. Patient. 2021;14(5):533–543. doi:10.1007/s40271-020-00485-w.

- Balp MM, Krieger N, Przybysz R, et al. The burden of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) among patients from Europe: a real-world patient-reported outcomes study. JHEP Rep. 2019;1(3):154–161. doi:10.1016/j.jhepr.2019.05.009.

- Cook NGA, Schmid A, Hirschfield G, et al. The patient perspectives on future therapeutic options in NASH and patient needs. Front Med (Lausanne). 2019;6:61. doi:10.3389/fmed.2019.00061.

- Swain MG, Pettersson B, Meyers O, et al. A qualitative patient interview study to understand the experience of patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatol Commun. 2023;7(3):e0036–e0036. doi:10.1097/HC9.0000000000000036.

- Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, et al. Content validity–establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO good research practices task force report: part 1–eliciting concepts for a new PRO instrument. Value Health. 2011;14(8):967–977. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2011.06.014.

- Shinde S, Kulkarni R, Saraykar T, et al. Abstract 1647 - Using social media intelligence to gain patient insights on nash symptoms, impact on quality of life, perceptions on disease and unmet needs. Presented at AASLD: the Liver Meeting. November 4–8, 2020.

- Lazure P, Tomlinson JW, Kowdley KV, et al. Clinical practice gaps and challenges in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis care: an international physician needs assessment. Liver Int. 2022;42(8):1772–1782. doi:10.1111/liv.15324.

- Vilar-Gomez E, Martinez-Perez Y, Calzadilla-Bertot L, et al. Weight loss through lifestyle modification significantly reduces features of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(2):367–378.e5. Augquiz e145. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.005.

- Anstee QM, Hallsworth K, Lynch N, et al. Real-world management of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis differs from clinical practice guideline recommendations and across regions. JHEP Rep. 2022;4(1):100411. doi:10.1016/j.jhepr.2021.100411.

- Hennink M, Kaiser BN. Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: a systematic review of empirical tests. Soc Sci Med. 2022;292:114523. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114523.

- Loria A, Escheik C, Gerber NL, et al. Quality of life in cirrhosis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2013;15(1):301. doi:10.1007/s11894-012-0301-5.

- Bedossa P, Poynard T. An algorithm for the grading of activity in chronic hepatitis C. The METAVIR cooperative study group. Hepatology. 1996;24(2):289–293. doi:10.1002/hep.510240201.