Abstract

James Hector produced the first geological map of New Zealand in 1865, based on local surveys by Ferdinand Hochstetter (Auckland and Nelson), J. Coutts Crawford (Wellington), Julius Haast (Canterbury) and his own mapping in Otago. Three updated versions of the map were produced in 1869, 1873 and 1884. Under Hector's direction, the New Zealand Geological Survey delineated the main geological features of New Zealand, but it was to be many years before the Alpine Fault was recognised and the problems of dating and correlating the older rocks were resolved.

Introduction

Geology emerged as a distinct science in the early 19th century. The publication of William Smith's geological map of England in 1815 demonstrated an effective way of presenting geological information for practical use (Winchester Citation2001) and led to the setting up of geological survey organisations in Britain, some European countries and some states of the USA. When the first geological map covering the whole of New Zealand was produced in 1865 by James Hector, this country was one of the few in the world to have a complete national geological map. This paper outlines the events leading up to the preparation of the 1865 map—exactly 50 years after the publication of William Smith's map—and subsequent revisions in 1869, 1873 and 1884.Footnote1

Some aspects of the production of these maps have already been covered by Willett (in Grindley et al. Citation1959), Burton (Citation1965), Collins (Citation1965) and McLernon (Citation1975), but considerable new information has come to light with the recent publication of letters between Hector and his colleagues (Burns & Nathan Citation2012, Citation2013; Nolden et al. Citation2012).

Early geological investigations 1858–64

Only scattered geological observations were made before geologist Ferdinand Hochstetter arrived in Auckland in December 1858 as part of the Austrian Novara expedition (Johnston & Nolden Citation2011). At that time, New Zealand was split into a number of semi-autonomous provinces () with a small central government. In company with his compatriot, Julius Haast, Hochstetter explored the southern part of Auckland Province and parts of Nelson Province, subsequently producing the first coloured geological maps of local areas (Hochstetter & Petermann Citation1864a,Citationb). After Hochstetter left New Zealand in late 1859, Haast explored the remoter parts of Nelson Province, and was subsequently appointed provincial geologist for Canterbury. Other provinces wanted to explore potential mineral resources, so James Hector, a young Scottish doctor and geologist, was appointed provincial geologist for Otago in 1861. J. Coutts Crawford, a local settler with scientific interests, took up a similar position in Wellington Province.

After returning to Europe in 1860, Hochstetter started to write an account of the geology of New Zealand. He was keen to include a geological map of the whole country to demonstrate his wide-ranging knowledge, but he did not have enough information. In particular, little was known about the geology of Otago or parts of the North Island. Hochstetter asked Haast to approach Hector a few weeks after his arrival in early 1862 asking for information about the geology of Otago. Not surprisingly, Hector responded that he could not give any information until he had explored the province (Nolden et al. Citation2012, letters 2 & 4). When the request was repeated a year later, Hector replied that he was still not confident about his knowledge of Otago geology (Nolden et al. Citation2012, letters 21 & 22).

1865 geological map

Otago industrial exhibition

Following the discovery of gold in Otago in 1861, the economy of the province boomed. In 1864, a group of prominent citizens started planning for an industrial exhibition, to be held in Dunedin in early 1865, that would show off the prosperity and investment potential of the province. By the middle of the year there were concerns that other provinces had not committed themselves to the exhibition, so Hector was asked by the Otago Provincial Council to travel around New Zealand rallying support and soliciting contributions. It was an opportunity for him to familiarise himself with the geology of the whole country and also meet the other scientists and local dignitaries. Hector arranged for a number of individuals and organisations to prepare displays for the exhibition, and also for several members of the; small scientific community to write essays about aspects of natural science, especially botany, geology and ethnology.

Hector planned to have illustrated essays on the geology of different provinces written by Crawford (Wellington), Haast (Canterbury) and himself (Otago). He realised that this material as well as maps produced by Hochstetter gave almost complete reconnaissance coverage of New Zealand geology, so he proposed to compile a single national geological map that could be referred to in each of the essays. For a young rising scientist he must have been well aware that it would enhance his status, both locally and overseas, to produce the first geological map of New Zealand.

An unexpected bonus for Hector was the decision of the central government to set up its own national Geological Survey. So while Hector was in Auckland—then the capital—he was asked for advice by the government, and a few days later offered a job when his contract with Otago Province was completed.

Geological issues

New Zealand has a huge variety of geology, with rocks ranging in age from early Paleozoic to Holocene, and considerable variation in different parts of the country. Hochstetter, Hector, Haast and their contemporaries arrived in New Zealand with concepts based on European experience (Nicholson Citation2003), especially beliefs that:

Coal-bearing rocks are Carboniferous (330–350 million years ago) in age;

Well-defined breaks occur between Cretaceous and Tertiary rocks as well as between Permian and Triassic rocks;

Hard, grey, deformed sedimentary rocks are old, probably Silurian in age; and

Widespread metamorphic rocks are generally older than sedimentary rocks.

In planning a geological map, one of the first challenges for Hector was to relate rock units in different parts of the country, and to work out their ages from fossil evidence. He was fortunate that Hochstetter's work in Auckland and Nelson provinces covered many of the main geological units in New Zealand, and that the fossils he collected had been described and dated by Austrian paleontologists (Beu et al. Citation2012). In particular, marine Triassic and Jurassic fossils had been described from Waikato and Nelson, and Hector subsequently found similar fossils in southeast Otago, helping to date some of the older rocks. Hochstetter had rapidly published the results of his New Zealand work (Hochstetter Citation1863; Hochstetter & Petermann Citation1864 a,Citationb) so that it was available to Hector.

The age of the coal-bearing beds was resolved at an early stage. Hochstetter had already established that the distinctive brown coals of the Waikato region are early Tertiary in age, and Haast and Hector had already dated coal measures they had seen in Canterbury and Otago as late Cretaceous or Tertiary, so it appeared that New Zealand lacked Carboniferous coal measures.

The most long-lasting issue was the age of the older sedimentary rocks, including the greywacke-type rocks that form the mountainous backbone of both North and South Islands. Fossils are rare, but those that were collected ranged from Permian to Jurassic, with isolated early Paleozoic fossils in northwest Nelson. It was a complex issue that was not fully solved until the late 20th century (Nicholson Citation2003). Most of the differences in late 19th century maps relate to different interpretations of the age of the oldest rocks.

Compiling the map

Crawford and Haast readily agreed to Hector's idea to prepare a national geological map, and provided material that he could use. While Crawford simply handed over his material, Haast wanted to be fully involved in the compilation, and the exchange of letters between Haast and Hector in November and December 1864 is documented by Nolden et al. (Citation2012). Haast was concerned about the problem of joining the maps over the boundary between Canterbury and Otago (Haast to Hector, 20 November 1864) as he and Hector appeared to have identified different rocks in the same area. With the benefit of hindsight, we know that the provincial boundary along the Waitaki River coincides with a major change in the older rocks from predominantly schist in Otago to predominantly greywacke in Canterbury, but this was an issue that was difficult to resolve in 1864 with the knowledge at hand. Haast was also cautious when he had little information, and left blank patches on the map. Hector wrote asking him to fill in unknown patches in Canterbury, guessing if necessary, as he didn't want gaps on the map. Haast was also concerned about how many people should be given credit on the map, especially for work in Canterbury, and raised this several times with Hector.

Hector hoped that he would be able to complete work on the map in late 1864 so that it would be ready to be displayed when the exhibition opened in January 1865. Unfortunately, he had underestimated the amount of work required to get the exhibition under way, especially as he ended up with much of the administrative responsibility. His first priority was to the exhibition as a whole, and secondly to get the Otago exhibits ready, including a giant geological map of Otago Province (Nathan Citation2011a), so the New Zealand map was left in limbo for several months. He returned to it in March or April 1865, when he used the services of draughtsman Thomas Forrester to prepare a master copy using pen, ink and watercolours. Forrester, who had been employed in an administrative role by the exhibition organisers, was a skilled architectural draughtsman, later to achieve distinction as the architect who designed many of the stone buildings in Oamaru (McCarthy Citation2002).

Hector started work for the New Zealand Geological Survey on 1 April 1865, although he remained in Dunedin for several months. In a letter to Joseph Hooker, dated 17 May 1865, he wrote: ‘By next mail I shall be sending home a complete Geological Map of New Zealand to Keith Johnston for Publication. I have filled up the corners with figures of our principal fossils like those on Forbes’ Geol Map of the Brit. Isles in the big Physical atlas. It is to be the first work issued from my new Department as per heading to the paper I write on.' Like many predictions that Hector made, this was over-optimistic. Three months later, the Evening Post of 21 September 1865 reported that the map had just been completed, and was to be sent to England for publication.

Unfortunately, Hector's plans for publication were thwarted by political changes. Edward Stafford was appointed Premier in October 1865, with a policy of reducing government expenditure. He declined to authorise publication of the map as a cost-saving measure (Mantell to Hector, 24 November 1865). By the following year, both Hector and Haast wanted to make changes to the map as a result of new fieldwork, and the map remained unpublished.

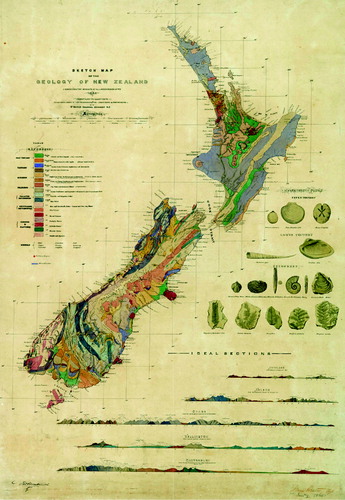

Notes on the 1865 map

The only copy of the 1865 geological map is now held at Archives New Zealand in Wellington. A reduced version is reproduced as . The map is labelled ‘Sketch Map of the Geology of New Zealand’, compiled to illustrate the geological essays of J.C. Crawford, J. Haast and J. Hector. Hector is listed as ‘Colonial Geologist NZ’. Although the date on the map, in Hector's handwriting, is given as January 1865, this is apparently an error as the map was not completed until later that year—or perhaps it represents the time that the map was started.

The map is a careful reduction of existing geological maps by Hochstetter, Crawford, Haast and Hector. Some areas are shown in great detail, but there is little information in other areas, especially Taranaki, Northland, and parts of the east coast of the North Island. Nevertheless, the main features of New Zealand geology are clear, especially the greywacke mountains of both islands, the schist belt of Otago, volcanic rocks around Auckland, the central North Island, Taranaki, Banks Peninsula and Otago Peninsula, and the widespread mudstone in parts of the North Island.

The geological legend was the subject of considerable discussion between Haast and Hector, and the resulting classification was a compromise as the age of many units was uncertain. There are two Tertiary units (Pliocene and Great Brown Coal Formation), two Mesozoic units (Upper and Lower) and two Paleozoic units (Upper and Lower) as well as units for metamorphic and igneous rocks. Although Mesozoic and Paleozoic fossils had been found at different localities, the extent of rocks of these ages was quite uncertain, especially as the change in rock types across the Alpine Fault had not been recognised. The main mountain ranges are shown as Lower Paleozoic, with a belt of Upper Paleozoic rocks to the east in the South Island.

The relationship of different rock types was illustrated by five east-west geological cross sections across the country, from Auckland to Otago, which are useful to clarify the structural relations visualised by Hector, especially the tightly folded deformation of the older rocks. Illustrations of a selection of Tertiary and Mesozoic fossils prepared by Hochstetter's colleagues in Vienna were used to fill a gap in the map, and it seems likely that Hector wanted to emphasise the similarity with fossils already recognised in Europe.

1869 geological map

Hector spent the 1866–67 summer carrying out a reconnaissance survey of Northland (Burns & Nathan Citation2013) and the following year he visited northwest Nelson and the west coast where both he and Haast had explored previously unknown areas. There was considerable new information to add to the geological map.

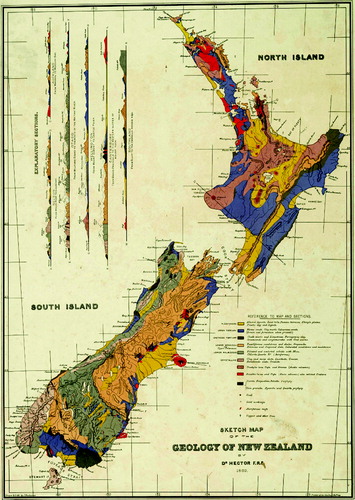

In 1867, the Government Printing Office set up a Lithographic Branch, and was then able to print coloured geological maps (Glue Citation1966).The 1869 map (), drawn and lithographed by Hector's draughtsman, John Buchanan, was printed by the Government Printer on a newly obtained lithographic press. Although the title is still ‘Sketch map of the geology of New Zealand’ it is a completely new map. Whereas the 1865 map was largely a reduction of existing provincial maps, the 1869 version generalises the existing geological information over the whole country. There is a simple legend for sedimentary rocks:

Pleistocene

Upper Tertiary (including brown coal seams)

Cretaceo-Tertiary (includes bituminous coal seams)

Lower Mesozoic & Upper Paleozoic

Lower Paleozoic (includes metamorphic rocks)

All the greywacke-type rocks in the mountains of North and South Islands are shown as part of a single Lower Mesozoic and Upper Paleozoic unit.

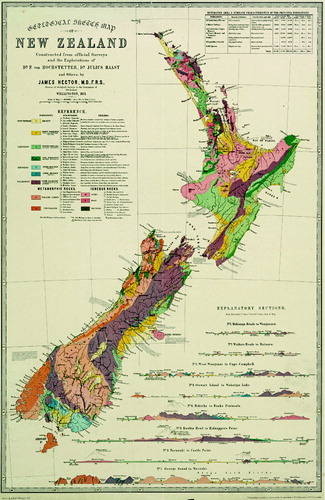

1873 geological map

It is surprising that a completely new geological map was published in 1873 () only four years after the 1869 map. This map (and a companion topographic map) was specifically prepared for the International Vienna Exhibition in 1873, where New Zealand had a large display that was curated by Hector, with assistance from Haast (Anon. Citation1873; Hector Citation1877, p. v). Hochstetter was a member of the organising committee, and gave considerable help setting up the New Zealand exhibits. It appears that the production of the maps was an initiative from the newly created Public Works Department, aimed at illustrating New Zealand's progress in developing roads, railways and mineral resources (Brednich Citation2012 and personal communication).

The map was compiled by Hector, and specifically mentions contributions by Hochstetter and Haast. It was draughted by Augustus Koch, a leading Wellington artist and cartographer who had accompanied Hochstetter as artist on his North Island expedition in 1859 (Johnston & Nolden Citation2011). The map was sent to London where it was printed under the supervision of Mr E.G. Ravenstein FRGS, an experienced cartographer.

The legend of the 1873 map is similar to the 1869 version, but slightly more elaborate, with separate Upper Mesozoic, Lower Mesozoic and Upper Paleozoic units, the latter including all the greywacke rocks of mountains. It had originally been intended to subdivide these rocks, but as Hector and Haast could not agree they were left as undifferentiated Upper Paleozoic (Hector Citation1886, p. xxv).

The overall understanding of the stratigraphy of New Zealand was gradually increasing, and almost all the major stratigraphic units had been named and dated by 1873. Hector provided a list beside the map legend. For example, the Upper Paleozoic unit contained four series in different parts of the country: Te Anau, Maitai, Rimutaka and Mount Arthur. He also provided a table showing the estimated area, surface characteristics and uses of the main stratigraphic units. It was a clear demonstration that understanding of New Zealand geology was reaching a sophisticated level.

1884 geological map

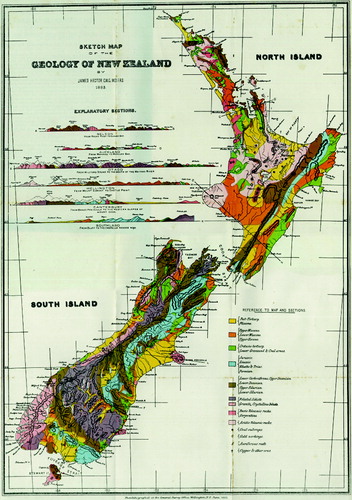

In 1871, Hector proposed that the Government Printing Office should investigate photolithography as a method of transferring data from complex plans to lithographic printing stone, and by 1873 new equipment had been installed, with considerable saving in time and money (Glue Citation1966).

The 1884 geological map was issued with the Reports on Geological Exploration for 1883–84 (dated 1884). A note on the map says that it was ‘Photolithographed at the General Survey Office, Wellington, N.Z. June 1883’, but for consistency it is referred to as the 1884 map. The same map, dated 1885, was reprinted for the Colonial and Indian Exhibition in London in 1886.

The overall appearance of the 1884 map () is close to the 1869 map because both maps use the same topographic base, with a dominating and rather idiosyncratic pattern of mountain ridges. The cartographer is not named, but was probably John Buchanan who drew the 1869 map, as the style of both maps is very similar. The sedimentary succession is generalised into only five major age units, with separate units for igneous and metamorphic rocks. Hector made many minor changes since earlier maps to incorporate the results of additional mapping. The most striking difference is in the colour pattern, which bears a close resemblance to modern geological maps, with yellow for Plio-Pleistocene, orange for Tertiary, green for Cretaceo-Tertiary and blue for Triassic-Jurassic.

In the accompanying text, Hector (Citation1884, pp. ix–xv) explained that he had incorporated the conclusions of the first and second International Geological Congresses, communicated to him by Dr A.R.C. Selwyn (director of the Geological Survey of Canada), both for the classification of different units and the colours used for rocks of different ages. It is interesting that Hector did not fully adopt the colour scheme as he claimed. For example, the colour suggested for Post-Tertiary is chrome green, whereas Hector continued to use yellow. Indian red is suggested for Triassic, but on the map it is grouped with Jurassic and coloured blue.

Throughout the 1870s there had been arguments between Haast, Hector and Hutton about the age and subdivision of the greywacke-type rocks of the mountains, based on their interpretation of sparse fossil collections. Hector (Citation1886, pp. xviii–xxi) gave a lengthy summary of the issue as he saw it. Haast (Citation1879) had proposed including all the rocks in his Mount Torlesse series, but Hector felt that he could distinguish an older, early Paleozoic group (coloured brown) from a younger Permian to Jurassic group (coloured blue) in the Southern Alps. Most of the evidence for dating has subsequently been modified or discredited which means that the 1884 map is regarded as less useful than earlier versions.

Discussion

An evolving map of New Zealand

The four geological maps have virtually the same title, ‘Sketch Map of the Geology of New Zealand’, slightly modified in the 1873 version to, ‘Geological Sketch Map of New Zealand’. As the unchanging nature of the title implies, the four maps are different editions of the same map that was progressively revised over a 20-year period.

The 1865 map is essentially a reduction of existing provincial maps, with little attempt at synthesis. The amount of detail shown on the map is a tribute to the skill of draughtsman John Forrester, but it actually obscures the overall map pattern. By the time that Hector had prepared the 1869 map (for which he was listed as the sole author), he had gained in experience and was able to generalise the main features of New Zealand geology. With hindsight, it was fortunate that this was the first map to be published and widely distributed rather than the 1865 version with its patchy detail. The 1873 map is a redrawn version of the 1869 map, and is arguably the most satisfying of all four maps, both from an aesthetic and scientific viewpoint.

Hector must have hoped that his 1884 map would have been the most advanced of all four. Unfortunately his attempt to subdivide the greywacke basement rocks was later discredited. But the colours he used for different units are recognisable to modern geologists, and are now widely used on New Zealand geological maps.

Although Hector's maps all bear a general similarity to a current geological map of New Zealand, a major difference is the absence of the Alpine Fault, a major strike-slip fault that cuts obliquely across the South Island and displaces key units by up to 480 km. To modern eyes, aided by aerial photography and satellite imagery, it seems extraordinary that such a major feature could have been overlooked, but 19th and early 20th century geologists did not think in terms of major faults as boundaries between rock units. It was more than 50 years before the Alpine Fault was discovered—in 1941 by Harold Wellman and Dick Willett—and there were many years of debate before large-scale transcurrent offset was generally accepted (Nathan Citation2011b).

Hector's legacy

One of Hector's main objectives while he was in charge of the Geological Survey was to produce geological maps of the whole country. These relatively small-scale maps were of little use for geologists and prospectors looking for minerals, and this was one of the factors that led to politicians becoming disillusioned with Hector's leadership of the Geological Survey. In 1892, the responsibility for geological work was handed to Alexander McKay, working directly for the Mines Department (Burton Citation1965). When the Geological Survey was reorganised in 1903, Hector's successors concentrated on detailed mapping of local areas, with emphasis on areas of mineral potential. A number of small-scale maps of the whole country were produced in the early 20th century (see summary by Willett, in Grindley et al. Citation1959, pp. 5–6), but all of these were simply modifications of Hector's maps.

A completely new national geological map was not produced until 1947 (New Zealand Geological Survey Citation1947). It was mainly a compilation of existing information, and demonstrated that many parts of the country had not been geologically examined since the days of Hector's Geological Survey. Ultimately this led to a new series of 1:250,000 geological maps (known as the ‘Four Mile’ series), produced between 1958 and 1967. With the development of mineral and energy resources, the demand for geological information grew rapidly in the second half of the 20th century, and another revision of the 1:250,000 geological map of New Zealand, known as the QMAP programme, was undertaken between 1996 and 2012 (Rattenbury & Isaac Citation2012).

One of the problems that bedevilled Hector and his contemporaries was the subdivision of the older greywacke-type rocks that underlie much of New Zealand, and this continued to be debated until the late 1990s (Nicholson Citation2003). It has only recently been resolved by the realisation that New Zealand consists of a series of juxtaposed tectonic slices or terranes that overlap in age, and come from different source areas. Recent mapping combined with laboratory work has shown that terrane boundaries can be identified. With hindsight we now know the answers to many of the problems that the first generation of New Zealand geologists were unable to solve. But they were not easy problems and it has taken their successors more than a century to resolve them.

Supplementary files

Supplementary file 1: Figure 1. Location map of New Zealand, showing provincial boundaries in 1865.

Supplementary file 2: Figure 2. High resolution image of James Hector's first geological map of New Zealand, prepared in 1865 but never published. Archives New Zealand, R17916934.

Supplementary file 3: Figure 3. High resolution image of 1869 geological map compiled by James Hector—the first published geological map of New Zealand. Archives New Zealand, R17916896.

Supplementary file 4: Figure 4. High resolution image of geological map of New Zealand produced for the 1863 Vienna Exhibition. Archives New Zealand, R17916894.

Supplementary file 5: Figure 5. High resolution image of 1884 geological map of New Zealand, published in the Reports of Geological Exploration for 1883–1884.

Figure 1. Location map of New Zealand, showing provincial boundaries in 1865.

Download JPEG Image (592 KB)Figure 2. High resolution image of James Hector's first geological map of New Zealand, prepared in 1865 but never published. Archives New Zealand, R17916934.

Download JPEG Image (4.6 MB)Figure 3. High resolution image of 1869 geological map compiled by James Hector–the first published geological map of New Zealand. Archives New Zealand, R17916896.

Download JPEG Image (5 MB)Figure 4. High resolution image of geological map of New Zealand produced for the 1863 Vienna Exhibition. Archives New Zealand, R17916894.

Download JPEG Image (5.6 MB)Figure 5. High resolution image of 1884 geological map of New Zealand, published in the Reports of Geological Exploration for 1883–1884.

Download JPEG Image (7.3 MB)Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Carolyn Hume for draughting the location map; to Kristin Garbett for finding obscure references; to Archives New Zealand for permission to reproduce Figs 2–4; to Rolf Bednich for information on Augustus Koch; to Sydney Shep for advice on 19th century printing methods; and to Steve Edbooke, Sascha Nolden, Mark Rattenbury and David Skinner for their helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was completed while I was an emeritus scientist in the Regional Mapping Department at GNS Science, and I am grateful for the use of research facilities.

Notes

1. The four maps are shown in –, but because little detail can be seen on the printed maps, high-resolution scans of the maps are available as supplementary files (SF Figures 1–5).

References

- Anon. 1873. The Vienna Exhibition, papers relating to. Appendix to the Journal of the House of Representatives H5: 1–23.

- Beu AG, Nolden S, Darragh TA 2012. Revision of New Zealand Cenozoic mollusca described by Zittel (1865) based on Hochstetter's collections from the Novara expedition. Association of Australasian Paleontologists Memoir 43. 69 p.

- Brednich, RW 2012. Augustus Koch (1834–1901) and Hochstetter's North Island expedition. In: Braund J ed. Ferdinand Hochstetter and the contribution of German-speaking scientists to New Zealand in the nineteenth century. Frankfurt, Peter Lang. Pp. 271–284.

- Burns R, Nathan S 2012. My Dear Hooker. Transcriptions of letters from James Hector to Joseph Dalton Hooker between 1860 and 1898. Miscellaneous Publication 133B. Wellington, Geoscience Society of New Zealand. 207 p.

- Burns R, Nathan S 2013. James Hector in Northland, 1865–1866. Miscellaneous Publication 133G. Wellington, Geoscience Society of New Zealand. 57 p.

- Burton P 1965. The New Zealand Geological Survey, 1865–1965. DSIR Information Series 52: 147 p.

- Collins BW 1965. Some geological maps of New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Geology & Geophysics 8: 901–913. 10.1080/00288306.1965.10428150

- Glue WA 1966. History of the government printing office. Wellington, Government Printer. 194 p.

- Grindley GW, Harrington HJ, Wood BL 1959. The Geological map of New Zealand 12,000,000. Wellington, New Zealand, Geological Survey Bulletin 66. 111 p.

- Haast von J 1879. Geology of the provinces of Canterbury and Westland; a report comprising the results of official explorations. Christchurch, Lyttelton Times. 486 p.

- Hector J 1877. Reports of geological explorations during 1873–4. Wellington, James Hughes, Government Printer.

- Hector J 1884. Reports of geological explorations during 1883–84. Wellington, George Didsbury, Government Printer.

- Hector J 1886. Reports of geological explorations during 1885. Wellington, George Didsbury, Government Printer.

- Hochstetter F von 1863. Neu-Seeland. Stuttgart, Cotta. 555 p. + folding maps. [English edition subsequently published in 1867]

- Hochstetter F von, Petermann A 1864a. Geological and topographical atlas of New Zealand: six maps of the provinces of Auckland and Nelson. Auckland, Delattre. 20 p. + 6 plates.

- Hochstetter F von, Petermann A 1864b. The geology of New Zealand: in explanation of the geographical and topographical atlas of New Zealand. Auckland, Delattre. 113 p.

- Johnston M, Nolden S 2011. Travels of Hochstetter and Haast in New Zealand, 1858–60. Nelson, Nikau Press. 336 p.

- McCarthy C 2002. Forrester and Lemon of Oamaru, architects. Oamaru, North Otago Branch, New Zealand Historic Places Trust. 128 p.

- McLernon CR 1975. Early geological maps of New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Geology & Geophysics 18: 745–751. 10.1080/00288306.1975.10421572

- Nathan S 2011a. James Hector and the Geological Map of Otago. Web feature, University of Otago library. http://www.otago.ac.nz/library/treasures/hector/index.html (accessed 29 January 2014).

- Nathan S 2011b. Harold Wellman and the Alpine Fault of New Zealand. Episodes 34: 51–56.

- New Zealand Geological Survey 1947. Geological map of New Zealand 1:1,013,760 [2 sheets]. Wellington, New Zealand Geological Survey.

- Nicholson, HH 2003. The New Zealand greywackes: a study of geological concepts in New Zealand. PhD thesis. Auckland, University of Auckland. 440 p.

- Nolden S, Burns R, Nathan S 2012. The correspondence of Julius Haast and James Hector, 1862–1887. Miscellaneous Publication 133D. Wellington, Geoscience Society of New Zealand. 315 p.

- Rattenbury MS, Isaac MJ 2012. The QMAP 1:250 000 geological map of New Zealand project. New Zealand Journal of Geology & Geophysics 55: 393–405. 10.1080/00288306.2012.725417

- Winchester S 2001. The map that changed the world: William Smith and the birth of modern geology. London, Harper Collins. 329 p.