ABSTRACT

New genetic tools can potentially mitigate the decline of biodiversity. Democratisation of science mandates public opinion be considered while new technologies are in development. We conducted eleven focus groups in New Zealand to explore three questions about novel technologies (gene drive and two others for comparison of pest control tools): (1) what are the risks/benefits? (2) how do they compare to current methods? and (3) who should be represented on a panel that evaluates the tools and what factors should they consider? Findings from the content analysis of the risks/benefits revealed three main considerations that were of social concern – Environmental, Practical, and Ethical. Most participants were self-aware of their insufficient knowledge to compare the different technologies. Unanimously, respondents wanted the available information provided throughout the tool development process and saw multi-sector panel oversight as essential. Scientists and policy makers should match the public’s willingness to engage collaboratively.

Introduction

Invasive species are a significant threat to biodiversity worldwide, especially to island nations such as New Zealand (Murphy et al. Citation2019). Emerging technologies, such as gene drive and pest-specific toxins have the potential to mitigate the decline (Campbell et al. Citation2015). However, novel technologies are often met with public apprehension (Ho et al. Citation2008; Akin et al. Citation2017) and perceived as high-risk (Gent et al. Citation2011; Kannemeyer Citation2017). Thus, if novel technologies for pest management are to move beyond the laboratory, the largest hurdle may be public opinion (van Eeden et al. Citation2017). Consideration of public opinion towards novel pest control technologies while they are in development is part of a responsible science paradigm (Ancillotti et al. Citation2016). Understanding public views and concerns early in the development process may prevent emotionally-reactive and polarised public conversations, as seen in the areas of stem cell research (Nisbet Citation2005), climate change action (Gifford Citation2011), and current pest management measures (Green and Rohan Citation2012). Drawing from across eleven focus groups, our study explored New Zealanders’ perceptions of gene drive and the decision-making process about its potential use for conservation (Bryman Citation2004).

New Zealand presented a useful case-study given the country’s strong environmental ethos, often viewed as part of the national identity (Seabrook-davison and Brunton Citation2014; Russell et al. Citation2015). Predator Free 2050 (Tompkins Citation2018), a government and community initiative to rid New Zealand of introduced predative pest species (stoats, possums, and rats), encapsulates the country’s strong conservation focus. This ethos sits in contrast to another strong national belief that is still held by many New Zealanders today – an anti-GMO sentiment and distrust of politically-supported scientific initiatives (El-Kafafi Citation2017). Finally, New Zealand has a long history of small animal pest management with an aerially delivered baiting of 1080 (sodium fluroacetate toxin). Though this method has been employed for decades, the New Zealand public has become increasingly emotionally reactive towards this tool use (Kannemeyer Citation2017). Indeed, public discourse on this topic appears to often manifest as highly emotive confrontation and polarisation, leaving little room for open, two-way discussion to explore future steps forward or for compromise (Bidwell Citation2012; van Eeden et al. 2017).

Building upon the limited quantitative studies to date that explore public attitudes towards genetic tools for conservation (Kohl et al. Citation2019; MacDonald et al. Citation2020) and the wider use for pest control for agricultural benefits (Jones et al. Citation2019), our study used content analysis to gain insight into New Zealanders’ perceptions of novel technologies for conservation. Eleven focus groups were conducted to explore three questions with regard to gene drive and two other forms of novel technologies for comparative purposes: the trojan female technique (Dowling et al. Citation2015) and a pest-specific toxin (Campbell et al. Citation2015). In brief, gene drive is a process where inheritance of a gene is biased in such a way that, compared to normal Mendelian reproduction, it has a greater than 50% chance of being passed onto offspring (see Supplementary Information for more details). In the context of pest control, gene drive could be used to spread a gene that increases the likelihood of male offspring. Done successfully, gene drive could therefore drastically reduce, if not eradicate, a given population (Royal Society Citation2017). The trojan female technique (TFT) would theoretically utilise the natural mutations, which occur on maternally inherited mitochondrial DNA as they impact male fertility. Through multiple releases of females carrying this mutation into the wild, the TFT could therefore result in population suppression (Wolff et al. Citation2017). The third technology explored was a species-specific toxin (Eason et al. Citation2017). Most current toxins cause observable effects in a range of species upon exposure, but a species-specific toxin would only impact the targeted species.

In our study, we began with an assessment of the perceived risks and benefits to the three novel tools as perceived risk and benefits have been found to be a key driver of public opinion towards 1080 pest management tools (Green and Rohan Citation2012) and novel technologies in general (Sjöberg Citation2004). We then explored how participants compared these new techniques to current tools to gauge how their overall viewpoints of pest control were formed. Finally, because citizen panels have been effective in engaging publics with emerging scientific issues in Europe (Forsberg et al. Citation2015; Dubois et al. Citation2019), we asked participants to evaluate the make-up of such potential panels and their potential scope of discussion.

Method

Participants

Participants for eleven focus groups (total n = 70) were recruited blindly through an external agency’s (Colmar Brunton©) research panel and offered financial incentive for their participation. Participants were recruited from two major cities (Auckland and Wellington) and one rural area (Hawke’s Bay) with representativeness across key demographics (see Table S1). Focus groups were conducted April-May 2018 and lasted no more than 90 min each. Participants gave consent for the sessions to be audio-recorded and transcribed by a third-party. All research was approved via the internal ethics board of Colmar Brunton and adhered to the Research Association NZ Code of Practice (a recognised derivative of the ICC/ESOMAR International Code on Market and Social Research).

Course of discussion

Focus groups were conducted by professional facilitators. Two focus groups were randomly attended by a co-author (JB) to determine adherence to the interview schedule. All participants were debriefed after the focus group sessions.

The focus groups began with general discussion around novel technologies as well as novel pest eradication methods in New Zealand to introduce the topic and warm up the group for the directed discussion. After introducing the terms ‘gene drive’, ‘Trojan female technique’ and ‘pest specific toxin’ to gauge initial reactions, participants were presented with definition cards for each method (see Supplementary Information).

The focus groups then explored three key questions:

Q1: What are the risks and benefits of using gene drive/ trojan female technique/pest specific toxins for conservation in NZ?

Q2: In what ways would the new technologies be better, worse, and/or the same as compared with what is currently being used?

Q3: Imagine an appointed panel whose role would be to make decisions about how to control pests that pose a threat to our native plants, animals, and natural environment. Which individuals or groups should be represented on this panel? What are the key factors that the panel should consider when thinking about introducing a new pest control tool?

Data coding

Constant comparative content analysis (a thematic analysis based on grounded theory) was used. Transcripts were coded using NVivo software. Following the protocol of Strauss and Corbin’s (Citation1990) three-step coding procedure of Open, Axial, and Selective Coding, the data was first coded at the statement level, where the statements could have multiple codes. Initial theme and sub-themes were identified and described to capture the data in a succinct manner. The themes and sub-themes were then refined, and any infrequent themes were either merged with existing themes or separated out. Any disagreements regarding themes were resolved via discussion between the coders. Next, responses were either coded as belonging or not belonging in a theme and sub-theme. Once coded, a random subset (25%) of the transcripts were given to an author (EM) to establish intercoder reliability, which was at an acceptable level (90.63%).

Results and discussion

Question 1: risks and benefits

Analysis of the overarching themes across participants’ perceptions of both risks and benefits produced six themes and sixteen sub-themes covering roughly 94% of the data ().

Table 1. Overall perception themes and sub-themes for the Risks and Benefits question. Percentages represent the proportion of statements per theme (bold) and sub-theme.

Environmental considerations

Environment Considerations pertained to the numerous statements which concerned the overall effect the technology could have on the environment, often with specific mention of soil, waterways, or the ‘naturalness’ of the tool. Within the Environmental Considerations theme, there were two sub-themes, Specificity Considerations and Balance of Nature. Specificity codes were the most widespread and concerned the potential by-kill or impact on other species the tool could have and was present in both benefit and risk evaluations. Balance of Nature considerations detailed the order of the ecosystem and how its equilibrium could be disrupted with the use of the technologies.

You get rid of one pest what is going to fill that gap? Is it going to be wild cat predators or is it going to be mice or weasels or stoats or ferrets? (FG 10)

Despite previous research in which balance of nature considerations dominated the risk factors overall (Frewer et al. Citation1997; Macnaghten et al. Citation2015) in our study this was the smallest sub-theme within the broader Environmental Considerations theme with very few of such considerations being expressed.

Practical considerations

Practical Considerations encapsulated statements about the production and maintenance of the tools. Within the Practical Considerations theme, there were four sub-themes in descending order: Control, Costs, Timeframes, and Delivery Method.

While previous research in New Zealand found strong opposition to aerial distribution of 1080 but not hand-laid bait (Green and Rohan Citation2012), we found very little mention of delivery methods. Aerial application of 1080 is often viewed negatively because of the perceived indiscriminate nature of the toxin (Kannemeyer Citation2017), so it could be that participants were less concerned with delivery as the novel tool would be species-specific. This interpretation is supported by statements in the Control sub-theme which dealt mainly with whether the tool could be ‘taken back’ or contained should applications go wrong. Overall, the more control participants felt there was over the novel tools, the more they felt it would be beneficial to New Zealand (and vice versa).

It’s controllable. The long-term effects are that you’re just affecting a particular pest animal or species. Environmentally there’s no negatives seen. (FG 3)

Ethical considerations

Ethical Consideration pertained to statements which weighed moral or ethical concerns regarding the novel tool. Previous research (Green and Rohan Citation2012) placed such statements under Environmental themes, but we saw our data as more related to the moral dilemma, i.e. if humans had the ‘right to wipe out a whole species’, rather than the ecological consequence or outcome of eradicating a species. Within the Ethical theme, there were three sub-themes: Humane, Eradication Concerns, and Pest Definition.

Of the sub-themes, the Humane one was the largest and dealt mainly with statements related to the treatment and death of the affected species. Participants were concerned with how the novel toxins would kill animals (i.e. how painful a death) and the quality of life of the genetically altered species. Humane considerations were greater when discussing the benefit than the risks, especially for TFT and gene drive.

The death of the animal that we are targeting is of natural reasons so they don’t die by unnatural causes, and because we don’t have fertile males then the population is going to decrease, it’s a nice way to get rid of species. (FG 8)

Eradication versus suppression considerations was an underlying and recurrent sub-theme throughout the discourse. A divide emerged among participants, with some believing eradication was the only way as suppression would require ongoing and extensive pest management. However, other participants were concerned with the ethical ramifications of a species being eradicated from New Zealand.

That’s to draw on that ethical question again about whether someone makes a decision on that is a pest so we are going to eradicate it, but that is the whole God complex. (FG 2)

Societal considerations

Societal Considerations referred to statements about the impact on society. While societal considerations typically contain issues around human health and safety (Macnaghten et al. Citation2015), there were no such statements in our data. The two sub-themes which made up Societal Considerations were Public Opinion and the less frequent Livelihood Concerns. Public Opinion, like Ethical Considerations, related to the overall value of the public’s perception rather than outcome of the novel tool.

And then you’ve got the non-toxic approach which is a good thing for the social contract or the social buy-in from people, there’s no toxins that are out there. (FG 7)

Fear of genetic consequences

Fear of Genetic Consequences captures infrequent statements regarding possible mutations. These comments came out in more tangential conversations. Regardless of how beneficial participants perceived the technology to be, they were concerned with how the editing would affect the species. The concerns were less to do with genetic editing as a tool but rather any unintended (and unforeseeable) outcomes or side effects to the species (e.g. ‘super rats’).

There is so much potential for things to go wrong here, so I know the point is to eradicate but what I am saying is Super Rats. (FG 2)

Transparency

Transparency also appeared more in peripheral conversations and was often linked to a need for more details about the tool before committing one way or the other. Interestingly, the more a participant expressed they did not know enough about the novel tool (or the more uncertain), the more inclined they were to say the tool was risky.

So, I think that makes me an enemy straight away, there is no information about what the new toxin is, how it has been developed, how is it going to work and on the pests that might make it friendlier … . (FG 4)

Novel technologies

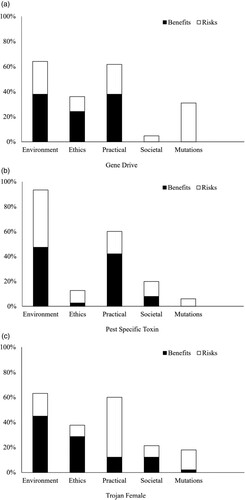

To further investigate risk and benefit evaluations of the different technologies, we split the overall evaluations by novel technology. Overall, there were more risk perceptions than benefits for gene drive, but similar risks and benefits for TFT and pest specific toxin (). It should be noted that this is not a reflection of whether participants support or oppose each tool but rather the aspects weighing on their mind when evaluating it.

Figure 1. Risks and benefits across the themes for A, gene drive, B, pest specific toxin, and C, Trojan female technique.

On the whole, the key considerations linked to risk perception varied across the three novel tools. In contrast, the themes and sub-themes linked to benefit perceptions were more similar ().

Question 2: comparison to current methods

Analysing how participants compared the novel tools to current pest management methods used in New Zealand proved to be difficult for two reasons. First, less than 20% of statements mentioned 1080 specifically. Despite facilitators initially introducing three current pest control methods (trapping, poison-bait laid by hand, and poison-bait spread by aircraft), participants discussed 1080 almost exclusivity compared to other current methods. Thus, there was insufficient data for any meaningful analysis. Second, most participants expressed a lack of knowledge (both at an individual level, as well as more broadly from the scientific perspective) which they viewed as limiting their capacity to make meaningful comparisons.

R1 I think the new methods sound more hopeful in regards to controlling the pest [on a] much larger scale.

R2 to me the pest specific toxin is just an upgraded 1080 it’s actually a better option to me whereas the others appear to be genetic driven which is I don’t know enough about it.

R1 That’s probably it we don’t know enough about it and with those other things we are familiar with them we have heard them for a long time so eventually that would probably be the same with these things after a while. (FG 11)

Instead of making specific comparisons, we found most participants described their feelings more generally. When they did refer to 1080, it was often to positively evaluate the novel technology, especially species-specific toxins, which they felt would be a better alternative to current methods.

Question 3: panel makeup

Our final question was in two parts; the first part was who participants felt should be on the panel. Participants felt the main representatives should be: Government Agencies (26%), Citizen Representatives (16%), Scientists and Academics (15%), Iwi (indigenous groups) (11%), Environmentalists (11%), Farmers (8%), Animal Activists (7%), Recreationists (4%), and Marketers (3%). Of the two leading themes, two sub-themes also emerged. Within Government Agencies a large proportion of responses were for the Department of Conservation. Within Citizen Representative, a large proportion of responses were for Future Generations (i.e. young people or succeeding generations). A large proportion of participants felt that the environment should be a paramount consideration and be made by the people who know and use the land. Within Scientists and Academics, they felt that the panel needed people who understand the science, the repercussions, and how it would affect the land, but importantly, they wanted them to be independent from corporate influence.

Well maybe scientists that don’t work for the company producing the thing, so independent. (FG 8)

Participants also felt strongly about iwi participation, both for their use of the land but also to have representatives on the panel to protect cultural values when making decisions about the novel tools.

iwi … because of the fact that it’s earth, it’s partly to do with the air, spiritual heritage. (FG 11)

Panel considerations

In addition to who should be on the panel, we asked participants what the panel should consider when making decisions about the technology. This question is slightly different than asking about risks and benefits, in that it focused on what participants felt the panel should prioritise when deciding about implementing novel technology in conservation.

We first analysed the overarching themes for what participants thought the panel should consider, resulting in six broad themes and nine sub-themes, covering roughly 97% of the data (). The most common response was Societal Considerations followed closely by Practical and Environmental Considerations. The other three themes were: Define the Problem, Pros and Cons, and Ethical Considerations. While similar to the themes we found in discussions around risks and benefits, there were important and significant differences. Notably, not only was Societal Considerations the most important consideration, but within this theme, a novel subtheme emerged: Community Awareness – the need to involve and communicate/be transparent with the public (). Statements in this sub-theme ranged from political suggestions – such as putting possible decisions up for a public vote – to education initiatives, like discussing these methods in schools.

R5: Let NZers vote on it with really good transparent public education first.

R7: Explain what you’re going to do and how it’s going to work so those will understand it.

R1: I’m on transparency and openness. Having to make the public decide but they need to know how it’s going to affect them. (FG 3)

Table 2. Overall themes and sub-themes for panel considerations. Percentages represent the proportion of statements per theme (bold) and sub-theme.

Conclusion

Our study aimed to understand participants’ views about gene drive and two other emerging tools to control pests for conservation gains. Using focus groups, we built upon the emerging studies to date and provide insights into New Zealanders’ attitudes toward these tools. Despite having little knowledge of the tools, participants identified a range of benefits and risks to the new tools in a way similar to experts in the field (NASEM Citation2016). More risks were noted overall, which is typical of public opinion of new technologies such as gene drive (Brossard et al. Citation2019) and should be seen as a starting point for public discourse and part of the democratisation of science (Selge et al. Citation2011). Participants indicated that government and scientific representation would be essential for any future panel considering the development and application of these tools, suggesting that currently in New Zealand, these entities are considered trustworthy and competent to a public discussion about gene drive.

Importantly, our participants showed self-awareness of their lack of knowledge, as well as a recognition that there is currently insufficient scientific knowledge available to make any meaningful decision on these novel technologies. The former invites reflection on what kinds of information and processes might lead participants to feel more involved in the decision-making process and ultimately increase perceptions of democratisation of science in New Zealand. Participatory technology assessment (PTA), such as citizen juries and consensus conferences where more time is spent on providing participants with information as well as broader perspectives, offer a way forward (Kurath and Gisler Citation2009). On the other hand, the latter acknowledgement that there is, as yet, insufficient scientific knowledge reflects the Collingridge dilemma: while research and innovation can be influenced by societal engagement in the early stages of development, there is little evidential information to facilitate meaningful discourse of risks and benefits. Once the technologies or innovations are advanced enough to allow meaningful consideration of their social, environmental, and economic implications, they are already so deeply embedded in society that it is often no longer possible to meaningfully change direction or use (Collingridge Citation1980; Guston Citation2018). Consequently, research and innovation should include ongoing public engagement to allow for shared decision-making in the face of uncertainty as evidential information arises (Genus and Stirling Citation2018; Ribeiro et al. Citation2018; de Saille et al. Citation2020). Taking this approach may alleviate highly emotionally reactive and polarised discourse about the tools, as has been seen with other emerging technologies and current pest control methods in New Zealand. By taking an early, pro-active engagement tactic with the public, researchers can address the risks and concerns perceived by the public and have a dialogue about the tools by inviting the ‘contribution of alternative views from public’ (Roberson Citation2020). In doing so, New Zealand could avoid the unhelpful and sensationalist public discourse that has been witnessed with other genetic technologies (Caulfield and Condit Citation2012) and instead foster reflectivity and critique of scientific initiatives, inviting a more thoughtful vision of how to advance science and technology in New Zealand (Fujimura Citation2003). It is important to emphasise that this method of engagement does not ensure the public will accept or support these tools- that is not the purpose of the democratisation of science. Instead it ensures the public voice is heard and integrated into the decision-making process (Blok Citation2014).

In closing, the desire for greater public engagement and public participation in the decision making process was made explicit in the closing discussions of all focus groups who unanimously agreed what was needed: working in partnership with our community and the country to have better control (FG 11). This places the impetus on scientists and policy makers to match the public’s willingness to engage positively and collaboratively by providing them the with the means to do so.

Supplementary information

Download MS Word (29.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Akin H, Rose KM, Scheufele DA, Simis-Wilkinson M, Brossard D, Xenos MA, Corley EA. 2017. Mapping the landscape of public attitudes on synthetic biology. BioScience. 67(3):290–300. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biw171.

- Ancillotti M, Rerimassie V, Seitz SB, Steurer W. 2016. An update of public perceptions of synthetic biology: still undecided? NanoEthics. 10(3):309–325. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11569-016-0256-3.

- Bidwell SR. 2012. Talking about 1080: risk, trust and protecting our place. Dunedin: University of Otago.

- Blok V. 2014. Look who’s talking: responsible innovation, the paradox of dialogue and the voice of the other in communication and negotiation processes. Journal of Responsible Innovation. 1(2):171–190. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23299460.2014.924239.

- Brossard D, Belluck P, Gould F, Wirz CD. 2019. Promises and perils of gene drives: navigating the communication of complex, post-normal science. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 116(16):7692–7697. doi:https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1805874115.

- Bryman A. 2004. Social research methods: second edition. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Campbell KJ, Beek J, Eason CT, Glen AS, Godwin J, Gould F, Holmes ND, Howald GR, Madden FM, Ponder JB, et al. 2015. The next generation of rodent eradications: innovative technologies and tools to improve species specificity and increase their feasibility on islands. Biological Conservation. 185:47–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2014.10.016.

- Caulfield T, Condit C. 2012. Science and the sources of hype. Public Health Genomics. 15(3–4):209–217. doi:https://doi.org/10.1159/000336533.

- Collingridge D. 1980. The social control of technology. New York: Open University Press.

- de Saille S, Medvecky F, Van Oudheusden M, Albertson K, Amanatidou E, Barabi T, Pansera M. 2020. Responsibility beyond growth: a case for responsible stagnation. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

- Dowling DK, Tompkins DM, Gemmell NJ. 2015. The Trojan female technique for pest control: a candidate mitochondrial mutation confers low male fertility across diverse nuclear backgrounds in Drosophila melanogaster. Evolutionary Applications. 8(9):871–880.

- Dubois A, Holzer S, Xexakis G, Cousse J, Trutnevyte E. 2019. Informed citizen panels on the swiss electricity mix 2035: longer-term evolution of citizen preferences and affect in two cities. Energies. 12(4231):1–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/en12224231.

- Eason CT, Shapiro L, Ogilvie S, King C, Clout M. 2017. Trends in the development of mammalian pest control technology in New Zealand’. New Zealand Journal of Zoology. 44(4):267–304. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03014223.2017.1337645.

- El-Kafafi S. 2017. Genetic engineering perception in New Zealand: Is it the way of the future? In: A Ahmed, editor. World sustainable development outlook 2017: knowledge management and sustainable development in the 21st century, 200. New York: Routledge; p. 400.

- Forsberg EM, Quaglio G, O’Kane H, Karapiperis T, Van Woensel L, Amaldi S. 2015. Assessment of science and technologies: advising for and with responsibility. Technology in Society. 42:21–27.

- Frewer L, Howard C, Shepherd R. 1997. Public concerns in the United Kingdom about general and specefic applications of genetic engineering: risk, benefit, and ethics. Science, Technology, & Human Values. 22(1):98–124.

- Fujimura JH. 2003. Future imaginaries: genome scientists as sociocultural entrepreneurs. In: A. H. Goodman, D. Heath, S. M. Lindee, editor. Genetic nature/cultureanthropology and science beyond the two-culture divide. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; p. 176–199.

- Gent DH, De Wolf E, Pethybridge SJ. 2011. Perceptions of risk, risk aversion, and barriers to adoption of decision support systems and integrated pest management: an introduction. Phytopathology. 101(6):640–643. doi:https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-04-10-0124.

- Genus A, Stirling A. 2018. Collingridge and the dilemma of control: towards responsible and accountable innovation. Research Policy. 47(1):61–69.

- Gifford R. 2011. The dragons of inaction: psychological barriers that limit climate change mitigation and adaptation. American Psychologist. 66(4):290–302. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023566.

- Green W, Rohan M. 2012. Opposition to aerial 1080 poisoning for control of invasive mammals in New Zealand: risk perceptions and agency responses. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 42(3):185–213. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03036758.2011.556130.

- Guston DH. 2018. … Damned if you don’t. Journal of Responsible Innovation. 5(3):347–352.

- Ho SS, Brossard D, Scheufele DA. 2008. Effects of value predispositions, mass media use, and knowledge on public attitudes toward embryonic stem cell research. International Journal of Public Opinion Research. 20(2):171–192. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edn017.

- Jones MS, Delborne JA, Elsensohn J, Mitchell PD, Brown ZS. 2019. Does the U.S. public support using gene drives in agriculture? And what do they want to know? Science Advances. 5(9). doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aau8462

- Kannemeyer RL. 2017. A systematic literature review of attitudes to pest control methods in New Zealand. Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research. 1–49.

- Kohl P, Brossard D, Scheufele DA, Xenos MA. 2019. Public views about gene editing wildlife for conservation. Conservation Biology. 33(6):1286–1295. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13310.

- Kurath M, Gisler P. 2009. Informing, involving or engaging? Science communication, in the ages of atom-, bio- and nanotechnology. Public Understanding of Science. 18(5):559–573. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662509104723.

- MacDonald EA, Balanovic J, Edwards ED, Abrahamse W, Frame B, Greenaway A, Kannemeyer R, Kirk N, Medvecky F, Milfont TL, et al. 2020. Public opinion towards gene drive as a pest control approach for biodiversity conservation and the association of underlying worldviews public opinion towards gene drive as a pest control approach for biodiversity conservation and the association of under. Environmental Communication. 1–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2019.1702568.

- Macnaghten P, Davies SR, Kearnes M. 2015. Understanding public responses to emerging technolgies: a narrative approach. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning. 21(5):504–518.

- Murphy EC, Russell JC, Broome KG, Ryan GJ, Dowding JE. 2019. Conserving New Zealand’s native fauna: a review of tools being developed for the Predator Free 2050 programme. Journal of Ornithology. 160(3):883–892. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-019-01643-0.

- NASEM. 2016. Gene drives on the horizon: advancing science, navigating uncertainty, and aligning research with public values. Washington (DC): The National Academic Press.

- Nisbet MC. 2005. The competition for worldviews: values, information, and public support for stem cell research. International Journal of Public Opinion Research. 17(1):90–112. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edh058.

- Ribeiro B, Bengtsson L, Benneworth P, Bührer S, Castro-Martínez E, Hansen M, Jarmai K, Lindner R, Olmos-Peñuela J, Ott C, Shapira P. 2018. Introducing the dilemma of societal alignment for inclusive and responsible research and innovation. Journal of Responsible Innovation. 5(3):316–331.

- Roberson TM. 2020. Can hype be a force for good?: inviting unexpected engagement with science and technology futures. Public Understanding of Science. 29(5):544–552. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662520923109.

- Royal Society of New Zealand. 2017. The use of gene editing to create gene drives for pest control in New Zealand. Wellington: Royal Society of New Zealand.

- Russell JC, Innes JG, Brown PH, Byrom AE. 2015. Predator-free New Zealand: conservation country. BioScience. 65(5):520–525. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biv012.

- Seabrook-davison MNH, Brunton DH. 2014. Public attitude towards conservation in New Zealand and awareness of threatened species. Pacific Conservation Biology. 20(3):286–295.

- Selge S, Fischer A, van der Wal R. 2011. Public and professional views on invasive non-native species – a qualitative social scientific investigation. Biological Conservation. 144(12):3089–3097. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2011.09.014.

- Sjöberg L. 2004. Principles of risk perception applied to gene technology. EMBO Reports. 5(1):S47–S51.

- Strauss A, Corbin J. 1990. Basics of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Tompkins DM. 2018. The research strategy for a ‘Predator Free’ New Zealand. Proceedings of the Vertebrate Pest Conference. 28. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5070/V42811002. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1fg8405s

- van Eeden LM, Dickman CR, Ritchie EG, Newsome TM. 2017. Shifting public values and what they mean for increasing democracy in wildlife management decisions. Biodiversity and Conservation. 26(11):2759–2763.

- Wolff JN, Gemmell NJ, Tompkins DM, Dowling D. 2017. Introduction of a male-harming mitochondrial haplotype via ‘Trojan females’ achieves population suppression in fruit flies. ELIFE, May. 3(6):e23551.