ABSTRACT

Finding a conceptually informed and substantive means of understanding the value of higher education (HE) remains a challenging but crucial issue in the context of continued market-orientated policies. This article offers a way forward and posits that formal approaches to measuring the value of HE can only have currency if engaging in longer-term and sustainable notions of value given that many of the benefits of HE are manifest in less tangible, non-immediate and non-monetary outcomes. Capability perspectives are drawn upon better to capture the more developmental and longer-term value potentiality of a university education. We explicitly refer to three key spheres of value pertaining to personal, social and economic milieus that may be derived from HE. This approach moves beyond the utilitarian gain approach to value popularised in recent HE policy, in particular the Teaching Excellence and Student Outcomes Framework. Instead, it brings into play the significance of agency and selfhood as key value dimensions, and a broader conception of working life. The implications for engaging with future measurements of the value of HE are also discussed.

The context of current HE policy

Universities are under mounting pressure to demonstrate and promulgate the value that they create for their main beneficiaries. These most specifically concern students and graduates who share significant costs towards acquiring their qualifications, and employer organisations who ultimately valuate those qualifications. The fundamental question as to what is valuable about higher education and how this should be appraised connects to a number of existential challenges facing contemporary HE. These include the legitimacy and efficacy of its offerings and how successfully it serves the needs of significant stakeholders; the enhancement of current teaching and research so that it is aligned to shifting demands; and how to manage, measure and communicate its value back to the wider public and policy domain.

There appear to be three over-arching and inter-related contextual dynamics surrounding the ways in which HE is appraised and each is associated with a variety of related policy drivers. First is the continued movement towards systemic massification, reflected in growth in participation and the international flow of students between national systems, even if the latter has been disrupted by the current pandemic. Second is the movement towards marketisation and related charges for institutions and their institutional actors – academics, students, senior managers – to be more entrepreneurial and transactional in how they approach institutional life. Third has been the changing economic context surrounding universities, evident in mutable patterns of graduate employment within a more flexible and uncertain labour market for the highly qualified (Institute for Fiscal Studies [IFS], Citation2020). These contextual dynamics provide a significant frame by which policy influencers seek to develop the means by which institutions can improve their outputs and demonstrate their social and economic worth.

The fundamental activities of universities are teaching and research. The desire for excellence in both has considerable traction in the way institutions are organised and on their self- and public image. They also affect how institutions respond to renewed governmental demands for enhanced outputs and engaging the societal and economic value of their core activities. In research terms, the UK’s current Research Excellence Framework provides an overarching evaluative tool intended to measure the quality and impact of institutions’ research outputs within a competitive ordering of institutional profiles. The relatively new(er) Teaching Excellence and Student Outcomes Framework (hereafter TEF) is also a significant lever for ensuring universities are accountable to both taxpayers and fee-paying students and, therefore, responsive to market demands. The framework has at its core the transparent dissemination of institutional performance data on key areas purportedly related to teaching quality, upon which basis prospective students can make informed investment choices.

This is the context and associated policy climate in which present-day UK universities are operating. The core aim of this article is to offer a broader conceptualisation of the benefits of higher education for individuals, showing its value and impact in many domains of graduate life. A related aim is to stimulate further engagement with the wider value of higher education at a time when the HE sector continues to face considerable challenges concerning its capacity to confer benefits and tangible gains for individuals and wider society. The main point of discussion is first degree qualifications, given the current policy orientation, in particular the assumptions built into the TEF framework.

The article is structured as follows. It first provides an outline of dominant approaches to understanding the value of HE, what here is termed a ‘dark side’. This is a largely performative and reified value frame that strongly equates the worthwhileness of university pursuits with its formal measurement on externally referenced criteria. The TEF is shown here to epitomise this approach as it ostensibly utilises forms of measurement that consolidate institutions’ market status. The article then offers a more substantial value framing, drawing on Sen’s (Citation1985, Citation1999) conceptualisation of capability to show the relationship between value, selfhood and substantive freedom. The article positions the concept of value against three core domains where value is likely to be most manifest in graduates’ future lives – the personal, the social and the economic – all of which are connected to some degree. Given the preoccupation with economic growth, productivity and return within current policy, making linkages between value and working life and the all-pervasive employability agenda has wider implications for how graduates may appraise what is valuable within their future employment. Moreover, this carries significant implications for how we may move towards more dynamic measures that go some way towards capturing the less observable value-added that HE generates.

The dark side of value

A pervasive form of valuation has come to inform official thinking and related policy discourse on how the personal and public gains from higher education are assessed and best facilitated within institutions (Downs, Citation2017; Tomlinson, Citation2018). This can be described here as a ‘dark side’ because not only does it subvert alternative and potentially more worthwhile institutional aims but also generates a set of unintended consequences, not always favourable, for institutional relations and identities.

The overarching policy narrative associated with the marketisation project has established an economic value framework based on what some authors have referred to as a ‘financialisation’ of human experience (Downs, Citation2017; Martin, Citation2002). This contends that human pursuits are directed ostensibly towards maximising institutions’, individuals’ and society’s economic growth capacity and success. In his 2020 Reith Lectures, former Governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney (Citation2020), outlines the challenges surrounding the encroachment of market values and reasoning into areas of life traditionally governed by non-pecuniary goals. This brings into force a commercialisation effect that impels institutions to be organised along market logics in order to meet market-related desires, but all the while destabilising the pursuit of other collective goods that cannot be transacted in direct market terms. Accordingly, non-monetary or intrinsic motivations are crowded out by commodity values, with unintended social costs for moral and civic engagement and the normative rules by which human conduct is founded. It also enables the continued misalignment between real-term value – e.g. volunteering during a pandemic, undertaking additional childcare, performing a low-paid but essential job – and the market’s valuation of these undertakings.

Central to current policy formulations is a reified notion of what counts as significant and meaningful endeavour and how this should be pursued through institutional practices. This is largely founded on graduates’ capacity to generate economic value, both for themselves and for the wider economy, and is a dominant reference point by which the value of their experiences is appraised. Financialisation captures the preoccupation with material and measurable end goals within institutional life. Within the current HE environment this includes fiscal responsiveness (and increased rationalisation in an austere pandemic era), market competitiveness and economic impact within both a national and global ordering of institutions. The frequently invoked ethic of ‘value for money’ depicts the imperative for institutions to fulfil immediate and demonstrate economic outcome for a variety of stakeholders.

In a competitive market environment, the objects of value that academics and students engage in and reproduce are configured in such a way as to commodify and instrumentalise core pursuits to showcase their wider economic value. This is true for both academics and students. The evolving ‘prestige economy’ surrounding academic work (Blackmore, Citation2016) operates through valorising achievements that conform to a variety of status markers that have largely performative value. The successful achievement of such visible markers – for example, grant capture, research impact, citation scores – begins to carry as much significance for academic worth and identity as the intrinsic value of research or the scholarship of teaching. For students and graduates leaving HE, pressures to compete favourably and be advantageously positioned within competitive and less accommodating labour markets have resulted in a growing commodification of achievements in order to enhance their positional value (Handley, Citation2018; Rivera, Citation2012). In both cases, a process of self-commodification is in operation whereby new market rules promote the formation and presentation of self-identities as productive and economically attuned.

Emergent in recent times is a largely performative conception of the value that HE generates: the value of any HE activity is inextricably linked to processes of metrification and quantification. One of the most prominent recent policy enactments of this is the Teaching Excellence and Student Outcomes Framework (TEF). The underlying principle of this policy framework was to enhance universities’ public accountability whilst also mobilising their market responsiveness by ensuring that information on their competitive standing via performance on key metrics is fed through to stakeholders. There are now numerous critiques of this policy framework, mainly concerning its problematic measurement principles in relation to often complex qualitative and subjective processes involved in teaching and learning (Barkas et al., Citation2019; Deem & Baird, Citation2020; Shattock, Citation2018). In summary, a number of themes stand out, including the preoccupation with outcomes that have only a partial and secondary relationship to the core activities they are measuring; the active endorsement of the student as a consumer who expects ‘value for money’ at the point of service; the transient and contingent nature of student satisfaction and employability; the segmentation of institutions who are engaged in zero-sum game competitive jostling rather than collaboration towards a greater good; and the serious lack of engagement with how excellent or high-quality teaching is constructed in this process. This policy framework is nonetheless highly pertinent to questions about how to engage with the value of HE and what its genuine benefits might be to students in both the immediate, and perhaps more importantly, longer term. All the dominant measurement approaches by which institutions are appraised – ‘successful’ graduate employment returns, consumer satisfaction and the incentivisation to undertake and successfully complete a university education – are infused with many of the reified value orientations outlined above.

Towards alternative conceptions

This present context therefore risks marginalising alternative sets of value beyond the material. This brings a key challenge in finding ways of engaging with the wider value of higher education beyond normative economic ones. One of the problems facing graduates, educators, institutional managers and policymakers is measuring the value and impacts of HE, a challenge which is compounded by the fact that many of the benefits derived from HE are not necessarily immediate, short-term and tangible. This task is not easy given that value has many dimensions, some of which can be in tension, and is also partly determined by time and context (Dollinger & Lodge, Citation2020). A related challenge is that there is often no straightforward bifurcation between instrumental and intrinsic value as they often work in parallel.

One of the pressures facing higher education, as evident in the TEF, is demonstrating immediate and short-term value pertaining to private gain. These are measured most conspicuously through student satisfaction and employment rates, but as ends in themselves these reveal little about quality of educational or employment-related experience. As Gibbs (Citation2019) discusses, the ‘goods’ that higher education potentially generates, including human flourishing, self-development, knowledge and civic engagement often elude formal measurement and cannot be easily attributed to the institutional practices through which they may be acquired. Furthermore, as a post-experience good (Brown & Carasso, Citation2013) higher education generates outcomes that potentially carry through well beyond the point of formal participation.

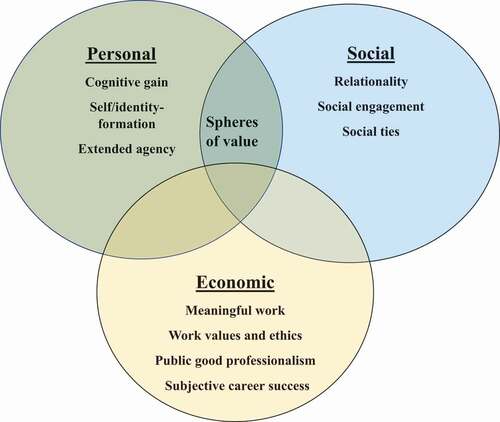

It is important therefore to work from a more nuanced and sustainable understanding of the value that HE generates and what it can offer individuals as agents in the quest for fulfiling an autonomous future existence. In this sense, value not only manifests itself in an individual’s private sphere but also in the social and economic milieus, in which its meaning is given context. Taking Sen’s Capability perspective as a starting point, this article presents a more substantial notion of value that emphasises agency building and a more holistic relationship to social and economic life in ways that enable individuals to pursue meaningful goals in their future lives. As a perspective that emphasises value in action and the pursuit of meaning and well-being as an ultimate goal, this approach is situated across three main domains of graduates’ future lives – the personal, social and economic. We show that each of these milieus, described here as spheres of value, overlaps in ways that produce individual and public-level effects beyond conventional notions of private gain that form the basis of current metrical approaches.

Capability and the value of HE

The most salient feature of Sen’s theorising around capability is the endeavour to shift understanding of well-being and human development beyond utilitarian markers of personal gain that predominate public policy. This approach transcends conventional understandings of utility as constituting an exchange value within a labour market for positional goods that enhances an individual’s self-optimising capacity to generate private returns. Instead, the orientation shifts to how successfully an agent can live the kind of existence they have reason to value. Human capital theory and its alternative sister concept, credentialism, frame the value of post-compulsory education in terms of positional benefit, whereas the capability approach strongly emphasises its agency-building potential. The object of value is centred less on the productive resources that an experience like HE generates and more towards its potential in creating desired states of being that enable individuals to pursue a meaningful future life-course. Whilst the former may be constitutive of the latter in the sense that a strengthened labour market position can notionally lead to an improved existential state, associated modes of measuring such value are confined to what is materially observable. In this case, value markers pertaining to contestable notions such as ‘return’, ‘value for money’ and ‘satisfaction’ refer to an observable property that has little to do with the life situations of those to whom these criteria refer.

Choice is a central component to capability approaches and connects to the wider notion of substantive freedom rather than the narrower conception of freedom implied in economic rationalism (A. Sen, Citation1995). In the restricted sense, a calculated choice centres on a set of available options within the wider labour market as determined by the strength of an individual’s potential to access, and then successfully negotiate, further desired employment outcomes. Choice in a highly marketised context is confined to the freedom to exercise agency around options that have largely economic salience. Choosing a suitable provider to help maximise future returns on investment, and then making sure they are accountable in meeting this goal, is one such expression of this agency. However, capability approaches frame choice as entailing real freedoms individuals have to pursue a range of options and outcomes that extend beyond market freedom. This includes the ability to resist superimposed ideas about what constitutes successful outcomes and cultivate alternative pathways towards self-actualisation.

Opportunity is also important here as it enables individuals to realise choices that are of meaning and value, but requires a supportive context for this to be pursued. Opportunity structures – for example, support networks, available jobs, conducive workplaces – enable people to exercise real freedoms and act meaningfully in the pursuit of life goals they come to value. Individuals often need a context for action, or to be in a position to create such a context, for substantive choices to be exercised to purposive effect. Developing a deeper realisation of what choice involves, how it can be pursued and what resources are available for its unfolding is central to a subject’s agential capacity to live independently and capably.

The allied concept of functioning is important in engaging the extent to which individuals are able to enact in practice the values associated with their life goals and intended pathways. Functioning is also not simply confined to what an individual does and has formally attained, but the capacity to knowingly undertake valuable acts or reach a valued state of being. Functioning refers to sets of outcomes (doings and beings) emerging from capability. These can encompass elementary forms of functioning like the ability to read, to more elaborate freedoms including free speech, choice of vocation and lifestyle. Central here is the agential capacity individuals have to pursue a set of alternatives which are meaningful and enable the capability sets they have acquired to be realised to purposive effect. Such agential capacity may nonetheless be hampered by either an individual’s unknowingness of their agency or of structural barriers that limit the scope for action. Well-being is central to the functioning capacity of individuals. Sen conceives this to be the subjective appraisals individuals make about the conditions of their being and centrally concerns individuals’ assessment of their capability and the substantive freedoms they have to pursue meaningful action. Substantive freedoms in the capability approach are such because they also constitute the reflective ability to (re)assess not just the object of value but its relation to the wider scale of existence.

Capability approaches largely emphasise the relative nature of value and the potentially multitudinous ways in which values may be expressed in relation to a formal undertaking such as education and employment. This means that individuals are not compelled to follow only one course of action which in the context of economic value has a defined object of value (e.g. strong economic resource, high salary, status). More significant is the capacity of the valuing subject to exercise judgment for themselves what they may come to value.

There are three potentials in this approach for engaging with understanding the value of HE (see ). Firstly, it enables us to work through value more in terms of individuals’ agency as connected to substantive freedoms and choices that go beyond private economic gain in the narrow sense. Related to this is the capacity for action which enables individuals to pursue goals and pathways that they have reason to value. Secondly, it can help understand how these outcomes are played out in the wider social and public sphere in which graduates engage, whether in their wider societal activities or within working life.

Thirdly, and related, it offers a conception of working life and the meaningful contribution that highly educated individuals can make in the wider economy. This enables a better understanding of the relationship between the activities of HE and the workplace beyond current functional approaches to employability development. Related is the challenge of developing an enhanced understanding of career ‘success’ and how formally to engage with this given the different assemblages of values that shape how individuals approach, and derive meaning from, working life. We now explore higher education’s wider value against these three domains.

The personal sphere: cognitive gain and extended agency

A salient question when appraising the value of HE at the level of the individual is how its formal and informal dimensions may effect personal and behavioural change in individuals. The first value manifestation centres on individuals’ personal milieu, mainly in terms of substantive development of individual capability and associated scope for empowerment. Two salient potentialities stand out here. The first concerns cognitive gain, often understood to emerge from formal engagement with disciplinary study. The second has a more psychosocial component and relates to the development of identity and sets of personal and socio-cultural dispositions, encompassing to a large degree individuals’ perceived sense of agency and action frame. Whilst the former is largely a formal outcome and linked to formal institutional processes and measures, most explicitly formal examinations and a core curricula, the latter’s construction and manifestation is often associated with more informal and less situated practices which are harder to formally assess.

Current policy frameworks contain an underlying assumption about personal gains derived from HE and their connection to students’ goal directions and agency. This has tended to be ostensibly market orientated and, by association, economic in its framing of the private outcomes: the exchange value of formal qualifications boosts the personal positionality of the graduates that in turn leads to enhanced earning capacity. ‘Higher education is a life-enriching experience which can positively enhance many different aspects of a person’s future – including their future earnings’ (Department for Business, Innovation and Skills [DBIS], Citation2016). Market-orientated policy, such as TEF, equates investment returns with personal gain which mitigates the costs of study. Reifying credentials effectively decouples them from the cognitive labour or transformative intellectual states on which their attainment is likely to be based. In a similar way, ‘skills’ acquired through HE have alleged utility value for individuals but, framed as crude employability dimensions, are often disembodied from experience. Significant theoretical work has substituted the notion of static skills with that of skilled social action concerning an agent’s capacity to use resources and decode rules towards eliciting cooperation among significant others in a given social context (Fligstein, Citation2001). This implies a set of reflexive capabilities on which to form appropriate social and affective behaviours that enable them to work with multiple conceptions of identity.

A wider conception of personal value moves closer to the policy aspiration of higher education’s ‘life-enriching experiences’ than those represented by functional utility and instrumental credentialist approaches. The notion of substantive development also brings sharper focus on the role of knowledge and its relationship with personal gain. The bedrock of disciplinary organisation within HE has been the body of knowledge formed within institutions and reproduced by academics and students. Given its structure, form and research basis, HE is seen to be at the apex of ‘powerful knowledge’ – a concept which has gained increased traction in recent times (Wheelahan, Citation2010; Young & Muller, Citation2013). This denotes specialised and advanced technical knowledge embedded within disciplinary structures and differentiated from everyday understandings of immediate reality. As the concept implies, this has empowering potential through opening up cognitive spaces and reordering extant epistemic frameworks. Beyond this, it has meta-value; enabling students to reflect on, and evaluate, different bodies of knowledge as well as their own relation to dominant scientific and socio-political regimes of truth. Overall the personal value of powerful university-level knowledge is enabling for students to make informed choices in the face of increased uncertainty and abstraction, including in fluid workplace contexts that demand greater levels of abstraction (Wheelahan, Citation2010).

The second main personal source of value from HE is around its role in enhancing self-identity, which some authors have referred to as a process of self-formation (Marginson, Citation2014) and others, such as Barnett (Citation2017), have referred to as ‘dispositions’. Irrespective of the terminology, at stake is the capacity for any meaningful experience associated with HE to provide a set of resources upon which an individual can make purposive decisions about the course of their lives and how they can further cultivate this. These have a close connection to capability as they connect to agency in ways that provide a framework of values and enable an individual to exercise substantive freedoms. They further convey an extended idea of self-identity that encompasses ontological shifts in how students experience themselves in context. The dispositions or ‘qualities’ which Barnett (Citation2017) sees as central to the idea of contemporary university education – willingness to learn, to engage, openness to experience and resilience – entails processes of ontological change which are now potentially as valuable as formal knowledge acquisition. The formation of such dispositions are crucial to how meaningful future actions may be pursued and provide a pathway to a worthwhile identity. Therefore, if one of the potential personal gains is self-formation through disposition building, this kind of value provides a framework for action that empowers students through enhanced agential freedom. This also shapes their future relations to social and economic life, outlined next.

The social sphere: value and relationality

A critical issue at stake is how individual-level benefits that have potentially strong internal value may further impact on an individual’s relationship to and within a social sphere where these benefits may be socially channelled. The concept of relational goods has emerged from behavioural economics in the past several decades and posits that much of the value in public life is often non-monetary and based on the quality of interpersonal relations and related intangibles such as accessing richer social experiences beyond consumer transaction (Uhlaner, Citation1989). Relational goods have a strongly interactional component, giving rise to social exchanges that are constitutive of relational outcomes, most notably connectedness, affiliation and social bonding. Significantly, they are not affixed a clear utilitarian value even within a market exchange relationship, although the by-product of relational goods can produce indirect market benefits such as workforce cooperation, well-being and shared knowledge. Relational goods, if purposive and meaning-making, therefore potentially transport a broad range of benefits for individuals including meaningful forms of inter-social exchange that flow through their engagement in public life.

The potential role of universities in generating relational goods is intimately linked to their institutional form and the wider social relations and outcome they encompass. As an institution, universities have endemic social properties; and the idea that the formal nature of HE learning is both highly relational and socially embedded has been acknowledged in much teaching and learning research (Ramsden, Citation1987). In this sense, its institutional form represents a shared community of knowledge production and exchange within an interacting field of practice, often comprising inter-connected communities (disciplines, societies, learning networks).

Three particular areas of social value derived from relational outcomes are salient to HE graduates: social engagement, social relationships and social ties. Each of these capture an embodied value that is also channelled through the public sphere and entails a collective point of reference. In framing social outcomes that have both market and non-market benefits, researchers) have highlighted systematic evidence of social/societal-level benefits from HE (Brennan et al., Citation2013 ; Hunt & Atfield, Citation2019). Similar overviews on wider benefits have been conducted in the US context (Chan, Citation2016; McMahon, Citation2009), reporting similar benefits. These tend to work from aggregate outcome measures from secondary data, including higher levels of political engagement, civic cooperation, reduced crime, healthier lifestyles, to describe the higher propensity for graduates to participate in areas of public life which might be beneficial to themselves and wider society.

Most of the existing research on graduates’ attributions of the value of HE has revealed an overall sense of expanded horizons, enhanced socio-cultural confidence, social efficacy and interpersonal development (Brennan et al., Citation2010; Pascarella & Terenzini, Citation2005). Such perceived gains appear to be the result of exposure to a broader range of cultural experiences, independent living and richer interactions within diverse institutional environs. This partly explains some of the spill-over effects this has on graduates’ wider engagement in public life mentioned above. A related implication is that some of the gains in individual students’ private milieu, not least an enhanced sense of agency, are worked through in future social contexts they encounter. It is also apparent that social goals and orientations are a motivating factor in relation to higher education study, whereby purely academic and vocational/career outcomes are often perceived to be only one component of HE’s offerings (Tomlinson, Citation2014). This is in contrast to the dominant depiction of students in policy whose motivation as a market leverager is in tension with a more developmental orientation. Therefore, more nuanced depictions of students’ relationship with their institutions in a contemporary environment have revealed goal orientations towards enriched social experiences that extend beyond formal study.

One of the further potentials of the social value of higher education is the interplay between relational goods and social capital formation and the reciprocal benefits these generate for individual graduates and their social environments. Conceived mainly as a resource that is acquired and transferred through embedded social relations, social capital works through reciprocal exchanges that extend individuals’ access to significant bodies of (often tacit) knowledge that open up opportunities structures (Granovetter, Citation1985). Crucially, this resource ultimately socialises the human capital that individuals have acquired in the educational process. Yet this does not necessarily have to be the kind of ‘investment in social relation with expected returns’ that Lin (Citation2001, p. 19) depicts, but also extended social ties that generate non-market associations – for example, political organisations, special interest groups, leisure.

Social capital development is clearly important for graduates who may have restricted access to weak ties outside of higher education as identified by a number of studies (Future Track Survey, Citation2012). Therefore, the value of social experience has significant equity implications if HE continues to have a role in reducing rather than reproducing social mobility gaps between advantaged and less advantaged students.

The economic sphere: value and valuable working lives

The personal economic value of HE is central now to how both public and private benefits of HE have been articulated, as well as how students are meant to define its impacts on their future place in the economy. The current policy framework would appear to endorse an ethic of possessive individualism where the primary measure of economic value is the return on investment in human capital. It follows that values are orientated towards leveraging the future status goods that higher education potentially generates. This constitutes a form of value rationality built around economic capital, enhancing the ‘productive resources’ it produces as measured in personal and collective rates of return.

Sen (Citation1999) acknowledged the meretricious nature of human capital gain as a core motivating factor towards educational activity but also its inherent limitations for understanding well-being in relation to economic activity. Human capital is the means of enhanced labour productivity and is a resource people draw upon for being positioned favourably in the division of labour, but it is one part, rather than a truly constitutive dimension, of the individual as an economic actor. More fundamentally at stake in relation to economic life is the freedom for individuals to have access to the kinds of experiences – through and around employment – that they have reason to value through the formation of value sets about what constitutes meaningful employment. The pandemic era has brought a renewed focus on the worthwhileness of different forms of employment and their relationship to core societal infrastructures (Stanford, Citation2020). The emergence of notions such as ‘key’ and ‘essential’ work signal a potential reappraisal of not only the intrinsic social value of forms of labour which may have traditionally been discarded as low-skilled or undesirable but also their role in society’s functioning.

The economic value associated with higher education relates significantly to how an individual graduate appraises their freedoms and agency around their future economic lives and the extent to which this may be enabled. Within the TEF, a significant means by which institutions are to demonstrate their market value for individuals is how successfully and quickly their graduates have secured employment, consonant with their level of education. The measurement of this – employment status and earnings – are not only markers of economic value but of institutional success towards achieving this end. The relative ability of graduates to return on their investment provides an indication of its material future benefits (IFS, Citation2020), and by association, the success of their participation in further study. An extension of this is to say that the graduate has used their economic agency, strategically and rationally, towards securing a favourable set of economic outcomes. The utility of skills acquired through university has further enabled their functionings as successful economic subjects and on this basis desired future outcomes have been realised.

The above approach to economic agency lacks a meaningful conception of working life or the social processes and relations that constitute economic activity. Largely neglected is an engagement with more nuanced understanding of the resources, other than economic or human capital, by which individuals become realised as so-called employable subjects. Significant here are the resources individuals have to become employable; not only in the sense of tools for autonomous and independent action so central to their capability but also other resources – social, cultural and socio-psychological – that enable them to navigate labour market structures. Notably, much recent research has re-conceptualised employability from skills/competences to capability and forms of capital that genuinely empower graduates (Tomlinson, Citation2017 Clarke, Citation2018). Resources such as their ability to form significant relationships with others (social capital) and informed culturally situated knowledge about workplaces (cultural capital) appear crucial in how their employability is negotiated.

Conceptualising value in relation to future employment brings into focus the ways that value is enacted through and around economic activity and also embodied by individuals during the course of their working life. This concerns the value people attribute to their working life which may be expressed through multifarious values and motivations. In this light, an apt definition of employability might be as follows: the capacity to be able to pursue and fulfil meaningful and desirable options in the labour market in order to fulfil and express their values. This not only concerns the meaning, value and satisfaction individuals derive in working life but also whether they perceive themselves to be making a significant contribution to their workplaces, society and significant others associated with their work. This can also be extended to employers given that the work contexts they regulate have a significant role in determining how well capabilities are converted. This further encompasses their commitment towards developing sustainable, equitable and healthy workplaces (a form of employer-ability) so that individuals are able to fulfil meaningful and equitable working lives.

One of the key findings to emerge from empirical work are the orientations graduates have shown towards expressive or intrinsic values, often more so than extrinsic ones which are taken to be the markers of employment success, namely higher pay and status (Jackson & Tomlinson, Citation2019; Quigley & Tymon, Citation2006). Whilst the latter outcomes are not inconsequential, they do not capture how individuals define themselves or perceive their longer-term sustainability in working life. Important to graduates’ understanding of their wider relationship to employment are the sense of being able to make a meaningful contribution, find creative fulfilment and establish purposive relations with significant others – in short, matters related to functioning autonomously and agentially and achieving desired states of being.

Unravelling notions such as job satisfaction, job quality and well-being from the wider construct of employability enables a broader conception of the interplay between value and values. This also leaves room for wider ethical dimensions, including vocational mission and public good professionalism (East et al., Citation2014) which, as concepts relating to wider capability sets, places the value of working life in a wider public and socio-political context. Economic agency in this sense is channelled through the ways in which an individual contributes towards working life that also potentially enriches the agency of others, wider institutional well-being and additional relational goods.

Discussions: challenges in re-articulating the value of HE

This article has engaged with a more substantial approach to value beyond what is offered in current and highly influential HE policy understandings and related measurement approaches. Taken together, the non-material benefits of HE – even within the economic sphere – contain value dimensions that often exist outside of current enactments, measurement imperatives and, increasingly, marketing strategies of what universities can offer.

Clearly of importance for key actors associated with universities is not so much what and how a higher education transforms individuals, but determining what is worthwhile and valuable for their wider life trajectories. An institution such as higher education explicitly and implicitly transits values that have scope to reproduce or subvert those supplied by government policy. One concerning tendency has been the ease by which institutions subscribe to dominant mantras that then become encoded within narrow value and capability sets. This institutional frame supplies related social and moral orders that confer normative identities that influence action: in a market context, the student as consumer and the academic as knowledge capitalist (Trowler, Citation2001).

However, a more polyvalent conception of value must work from an alternative understanding of the potentialities and possibilities a higher education experience might engender. A related matter is understanding how and through what contexts HE can offer value, yet a key challenge is that there appears to be no single site or episode through which various transformations may occur. Operating as it does across formal, co- and extra-curricular configurations, the university inhabits a variegated field of practice where different modalities of learning can occur in conjunction and, in cases where academic and social dimensions do not easily correspond, potential disjuncture. Dewey (Citation1939) captured this in the concept of collateral learning: valuable educational experiences are not just codified ones but also entail latent practices with latent effects. Values, attitudes and judgements learned through associated experiences are just as potent for the formation of educated subjects. Therefore, not only is the form and function of HE highly diverse, plural and contextual – and more so in mass systems – but its outcomes often extend beyond intentional instruction.

More immediate for those with an interest in the future development of universities, including the direction of policy, is finding ways of engaging with its wider benefits so that these are given greater oxygen within the dominant realpolitik of a marketised system. Current measures of value-for-money tell us little about how higher education works as a post-experience good and/or how its transformative potential is manifest. Needed instead are frameworks which go beyond simple substitute measures of value which currently comprise outcome data and at best qualitative data that amounts to elementary appraisals of a graduate’s labour market circumstance. These can enable institutions to feel they have more control and jurisdiction over institutionally associated outcomes data to develop contextually relevant policy to enhance process. There remains, however, a relative absence of extensive or rich data and alternative methodologies for engaging with how and what areas HE impacts on future lives beyond the material.

Each of the domains outlined above offers scope for engaging with value arguments and how it may be attributed to a university education, even though establishing specific and direct causal effects from higher education presents challenges (Brennan et al., Citation2013). The challenge lies in the disproportionate weighting towards static rather than dynamic measurement approaches. Whilst the former capture immediate and present circumstances, the latter are better able to gauge changes over time and context. If the continued trend towards outcomes surveys prevails, only longitudinal ones which engage with the range of capabilities and resources discussed here can work towards capturing how HE’s value is realised, articulated and acted upon. In the UK, for instance, the Destination of Leavers Survey (DLHE) has more recently incorporated university graduates’ insights on career and life satisfaction, retrospective perspectives on the value of their education, and insights on development over time. However, the only data used at scale in ranking and evaluating providers have been on employment status and salary outcomes. For instance, the 2020 University League Table from the Complete University Guide (2019) and the Guardian University Guide 2020 (Guardian, 2019) both use DLHE data on employment outcomes within six months of graduation, but not broader insights on career pathways or satisfaction.

In pursuing a more processual approach to capturing value over time and context, measurement would need to include graduates’ own appraisals of how the value of their higher education is expressed through multiple contexts, encompassing relations to social and working life. Significant work has already been done on establishing graduates’ views of their value to public spheres and how much this connects to capabilities acquired within HE and then further developed within professional fields (McClean & Walker, Citation2012; Walker, Citation2010). This necessitates reframing graduate outcomes away from static measures towards more dynamic and contextually referenced ones that enable appraisal of how graduates have utilised their value in ways that have enriched their, and others', social experience – be that in social, community or workplace settings.

Measurements need to engage with longer-term pathways into employment and how this is enacted through crucial employment episodes. Richer and more extensive insights from graduates on their career development, encompassing their perception of job value and quality, and how their careers have been supported, would also provide useful balance and context to data based on average salaries. Measurement platforms may also need to be delivered to individuals in simpler, more personalised ways with more comparable data between graduates with similar profile or cohort features and more clearly referenced against instutitonal profiles.

Data-based measures can also be enriched through transparency measures that include greater insight on how able students can access and engage with wider networks and form ideas about their future selves in relation to economy and society.

The employability agenda remains a considerable sticking point, not only in finding a meaningful way of measuring this but also attributing it to institutional practice. The problematic current measurement approach of equating employment status with successful outcomes, and then further attributing this back to assumed efficacious provision, risks conflating both. Engaging the economic value of HE beyond such measures requires a number of approaches. One of these is to engage with the extent to which graduates perceive that they have developed meaningful and sustainable career pathways and fulfilled a range of career-related values. Relatedly, there is considerable scope in engaging with individuals’ ‘subjective career success’ as markers of employment value and its relationship to wider dimensions linked to well-being, agency, choice and capacity to cultivate sustainable employment pathways. Qualitative and case study material over a longer term is of potentially considerable value in engaging with these issues (Novavokic, Citation2019). They allow for finer-grained judgements of how agency has developed and been applied through working life and richer assessments of career outcomes beyond an appraisal of how concordant employment outcomes are with their financial investment in HE.

Finally, the question emerges as to whether a pan-national framework such as the TEF is required to assess institutions’ offerings given the aforementioned diversity and inevitable variability in scale and purpose. A number of unintended consequences follow the zero-sum game model of institutional competition on which current TEF measurements are based. Providing institutions with the autonomy to develop their own framework based on specificities of student cohort and local contextual needs would enable meaningful sets of value goals and measures to be pursued upon which universities can look to enhance their offerings.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the reviewers for their helpful and constructive suggestions for improving this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Michael Tomlinson

Michael Tomlinson is an Associate Professor at the Southampton Education School at the University of Southampton, UK. His research interests include higher education policy and the higher education-labour market relationship. His previous books are Education, Work and Identity (2013, Bloomsbury) and Graduate Employability in Context (2017, Palgrave Macmillan).

References

- Barkas, L. A., Scott, J. M., Poppitt, N. J., & Smith, P. J. (2019). Tinker, tailor, policy-maker: Can the UK government’s teaching excellence framework deliver its objectives? Journal of Further and Higher Education,43(5), 801–813. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2017.1408789

- Barnett, R. (2017). The ecological university: A feasible utopia. Routledge.

- Blackmore, P. (2016). Prestige in academic life: Excellence and exclusion. Routledge.

- Brennan, J., Durazzi, N., & Tanguy, S. (2013). Things we know and don’t know about the wider benefits of Higher Education: A review of the recent literature. DBIS.

- Brennan, J., Edmunds, R., Houston, M., Jary, D., Lebeau, Y., Osborne, M., & Richardson, J. T. E. (2010). Improving what is learned at university: An exploration of the social and organisational diversity of university education. Routledge.

- Brown, R., & Carasso, H. (2013). Everything for sale: The marketization of UK Higher Education. Routledge.

- Carney, M. (2020). The Reith Lectures: From moral to market sentiments. BBC.

- Chan, R. (2016). Understanding the purpose of higher education: An analysis of the economic and social benefits of higher education. Journal of Education, Planning and Policy, 6(5), 1–40.

- Clarke, M. (2018). Rethinking graduate employability: The role of capital, individual attributes and context. Studies in Higher Education, 43(11), 1923–1937. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1294152

- Deem, R., & Baird, J. A. (2020). The English Teaching Excellence Framework: Intelligent accountability in higher education? Journal of Educational Change, 21(2), 215–243. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-019-09356-0

- Department for Business, Innovation and Skills. (2016). Success as a knowledge economy: Teaching excellence, social mobility and student choice. HMSO.

- Dewey, J. (1939). Education and experience. Chicago University Press.

- Dollinger, M., & Lodge, J. (2020).Understanding value in the student experience through staff-student partnerships. Higher Education Research & Development, 38(5), 940–952. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1695751

- Downs, Y. (2017). Further alternative cultures of valuation in higher education research. Cambridge Journal of Education, 47(1), 37–51. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2015.1102865

- East, L., Stokes, R., & Walker, M. (2014). Universities, the public good and professional education in the UK. Studies in Higher Education, 39(9), 1617–1633. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2013.801421

- Fligstein, N. (2001). Social skill and theory of field. Sociological Theory, 19(2), 105–125. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/0735-2751.00132

- Future Track Survey. (2012). Transitions into employment, further study and other outcome: The future track stage report 4. Warwick Institute for Employment Research.

- Gibbs, P. (2019). The three goods of higher education; as education, in its educative and in its institutional practices. Oxford Review of Education, 45(3), 405–416. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2018.1552127

- Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddeness. American Journal of Sociology, 91(3), 481–510. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/228311

- Handley, K. (2018). Anticipatory socialization and the construction of the employable graduate: A critical analysis of employers’ graduate careers websites. Work, Employment and Society, 32(2), 239–256. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017016686031

- Hunt, W., & Atfield, G. (2019). The wider (non-market) benefits of post-18 education for individuals and society. DFE.

- Institute for Fiscal Studies. (2020). The impact of undergraduate degrees on lifetime earnings. Department for Education.

- Jackson, D., & Tomlinson, M. (2019). Career values and proactive career behaviours among contemporary higher education students. Journal of Education and Work, 32(4), 449–464. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2019.1679730

- Lin, N. (2001). Social Capital: theory and research. New Brunswick: Transaction

- Marginson, S. (2014). Student self-formation and international education. Journal of Studies in International Education, 18(1), 6–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315313513036

- Martin, R. (2002). The financialization of daily life. Temple University Press.

- McClean, M., & Walker, M. (2012). The possibilities for university-based public good professional education: A case-study from South Africa based on the ‘capability approach. Studies in Higher Education, 33(5), 585–601. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2010.531461

- McMahon, W. W. (2009). Higher learning, greater good: The private and social benefits of higher education. John Hopkins University Press.

- Novavokic, Y. (2019). Researching longstanding graduates: Towards an enriched concept of the value of higher education. Cambridge Journal of Education, 49(6): 757–770. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2019.1607822

- Pascarella, E. T., & Terenzini, P. T. (2005). How college affects students: A third decade of research. Jossey-Bass.

- Quigley, N. R., & Tymon, W. G., Jr. (2006). Toward an integrated model of intrinsic motivation and career self-management. Career Development International, 11(6), 522–543. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430610692935

- Ramsden, P. (1987). Improving teaching and learning in higher education: The case for a relational perspective. Studies in Higher Education, 12(3), 275–286. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075078712331378062

- Rivera, L. (2012). Hiring as cultural matching: The case of elite professional service firms. American Sociological Review, 77(6), 999–1022. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122412463213

- Sen, A. (1995). Rationality and social choice. The American Economic Review, 85(1), 1–24.

- Sen, A. K. (1985). Well-being, agency and freedom: The Dewey Lectures. Journal of Philosophy, 82(4), 169–221. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2026184

- Sen, A. K. (1999). Development as freedom. Oxford University Press.

- Shattock, M. (2018). Better informing the market? The Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF) in British higher education. International Higher Education, 92(1), 21–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.6017/ihe.2018.92.10283

- Stanford, J. (2020, July 21). Work after COVID building a stronger, healthier labour market. Public Policy Forum.

- Tomlinson, M. (2014). Exploring the impact of policy changes on student attitudes and approaches to learning in higher education. Higher Education Academy.

- Tomlinson, M. (2017). Forms of graduate capital and their relationship to graduate employability. Education + Training, 59(4), 338–352.

- Tomlinson, M. (2018). Conceptions of the value of higher education in a measured market. Higher Education, 73(4), 711–727. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0165-6

- Trowler, P. (2001). Captured by Discourse: The socially constitutive power of the New Higher Education discourse in the UK. Organization, 8(2), 183–201. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508401082005

- Uhlaner, C. J. (1989). “Relational goods” and participation: Incorporating sociability into a theory of rational action. Public Choice, 62(3), 253–285. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02337745

- Walker, M. (2010). A human development and capabilities ‘prospective analysis’ of global higher education policy. Journal of Education Policy, 25(4), 485–501. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02680931003753257

- Wheelahan, L. (2010). Why knowledge matters in curriculum: A social realist argument. Routledge.

- Young, M., & Muller, J. (2013). On the powers of powerful knowledge. Review of Education, 1(3), 229–250. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3017