Abstract

The Vernacular Architecture Group Aisled Buildings Database is described. It contains entries for 391 aisled halls and 2,127 aisled barns, with a handful of other aisled buildings. Their distribution and dating are presented, and the remarkable 700-year date-span of aisled barns is emphasised. Individual features of the buildings in the database are summarised, including the number of bays and the roof types recorded for halls and barns.

INTRODUCTION

During an online talk to the Vernacular Architecture Group (VAG) a few years ago, the lecturer regretted the absence of any listing of aisled halls more recent than that published by Kathleen Sandall in 1986, itself a revision of her own 1975 updating of J. T. Smith’s original list of around 40 aisled halls.Footnote1 The present author, as the VAG bibliographer with responsibility for its online databases, took this as a challenge that should be taken up. In compiling such a database, the standard procedure would be to search the literature, but this would achieve little beyond correlating what is already known. Instead, since many (perhaps most) aisled buildings in England are likely to be listed as of ‘special architectural or historic interest’, the approach has been to search the Historic England Listed Building Database (hereafter HEL) for all references to aisle(s) (excluding churches).Footnote2 From the resulting list, primary information, including the HEL number, address and grid reference, was extracted and then the list description was checked, to confirm that the list did refer to an aisled building.Footnote3 Extra entries, such as aisled buildings recorded in other sources, were then added to the database, including those in Sandall’s Citation1986 list but not in HEL, those in other publications and in available individual building reports. Information from building records for Essex, East Sussex and North Yorkshire was kindly provided by researchers in these areas.Footnote4 Of these additions, 54 are indeed in HEL but are not described as aisled, indicating the limitations of the list, while almost 100 are not listed; the majority of these are aisled halls, about half of them demolished. The results have been collected in a spreadsheet that is publicly accessible through the Archaeology Data Service.Footnote5

Since the initial HEL data covered all listed aisled buildings other than churches, a key decision was taken not to restrict the database just to aisled halls. Although these have been the subject of several studies, aisled barns have received much less attention, apart from some reports on individual buildings and one map published in 1971.Footnote6 This extension beyond the original proposal proved to be onerous because of the large number of listed aisled barns, but has now provided their first systematic identification.

A number of larger buildings that survive mainly as upstanding ruins are also included, such as castle halls, monastic infirmaries and former medieval hospitals (whose main buildings were generally of aisled form).Footnote7 Demolished buildings, recorded in antiquarian records or drawings, have been included, when they can be located with reasonable accuracy. However, buildings known only from excavation, in particular those with ground-set aisled posts, have been excluded.

The very few aisled buildings in Wales have been studied in detail by Peter Smith (Citation1988), whose list has been used as the basis for the Welsh entries in the database. As far as the author is aware, no standing aisled buildings are known from either Scotland or Ireland, although documentary evidence identifies the construction of a great hall in Dublin Castle by Henry III, whose dimensions (120 × 80 ft), along with contemporary and seventeenth-century descriptions, indicate that it was aisled with stone piers.Footnote8

NOMENCLATURE

Historically, houses with aisles have been described as ‘aisled halls’. This is certainly appropriate for describing early houses, but perhaps less so for the late medieval or Tudor houses which might equally be described as aisled houses. However, an arbitrary distinction would then need to be made between ‘halls’ and ‘houses’, so it seems better to identify all aisled domestic buildings as halls. When discussing the room containing the aisle, rather than the building as a whole, Colum Giles in his recent paper has named it as the housebody rather than the hall but, similarly, the term hall is retained here.Footnote9

WHAT IS AN AISLED BUILDING? CRITERIA FOR INCLUSION IN THE DATABASE

Standard aisled buildings have or had at least one open truss of aisled form (with aisles on one or both sides), and have the structural type (field Type_Str in the database) of Aisled (–). Buildings where the evidence for aisles is uncertain have type P-Aisled. By contrast to an aisled structure, an outshut is divided from the main room, rather than open to it, although it is sometimes unclear whether the partition is original. An unusual type of aisled barn is found in northern England, not with aisle posts but with cruck trusses and with aisles extending beyond them, which are sometimes alternatively described as outshuts but are not divided from the body of the barn. Sometimes these aisles have been added, but others are clearly original;Footnote10 the dozen identified examples of this form of barn are included in the database, with the crucks mentioned in the notes field.

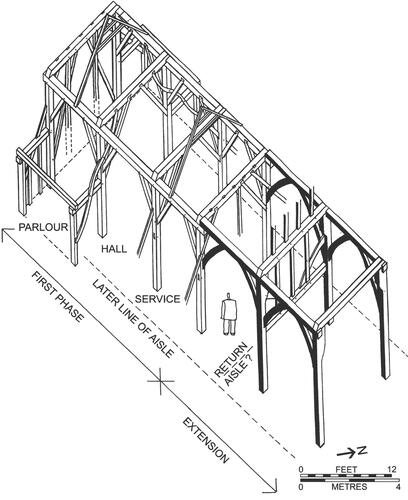

Figure 1. Reconstruction drawing of Songars, Boxted, Essex. Since only a few of the largest aisled halls remain open, a reconstruction like this provides the best view of a small aisled hall (from Stenning, Andrews and Tyers, 2003; drawing by Dave Stenning, © Vernacular Architecture Group)

Figure 2. Interior of the aisled barn at West Court, Binstead, Hampshire (1296–1304d) (© Edward Roberts)

Figure 3. Remains of the monk’s infirmary at Fountains abbey, Yorkshire (1220–47, doc), the largest known aisled hall ever built in England (c. 72 by 200 ft; 22 by 62 m). From an old glass plate held by the Wellcome Collection (CC BY 4.0)

A different type of medieval building has closed trusses of aisled form (or aisled end trusses set against a stone wall), accompanied by one or more open trusses, most often of base-cruck type; this is not surprising because of the close association between base crucks and aisled construction. Occasionally the central truss is of cruck or post-and-rafter form. These have not been classified as Aisled, but are included in the list with the structural type of Aisled closed/end truss; shows one of the most striking buildings of this type, which also includes a spere truss. This category also covers the not uncommon buildings where the central truss of the hall has been removed and its form is unknown, although the removal itself suggests that the truss may well originally have been aisled and that the aisle posts were found to be inconvenient.

Single-bay halls with aisled closed trusses can also be considered as having aisled characteristics. Five buildings of this type have been identified, all in Sussex, although they may well also await recognition in Kent and perhaps East Anglia. The handful of other halls listed as having only one bay are all fragments of longer buildings.

The final flourishing of aisled construction appears in the spere truss, a truss set at the lower end of a hall with a pair of posts defining a wide opening. What are generally the earlier examples occur in association with aisled end trusses (e.g. ), but they are also found in buildings with no other aisled features (e.g. ). Buildings with a spere truss but without aisled closed trusses have the type Spere truss; they have been added systematically to the database by searching HEL with the distinctive term spere and eliminating those included under another term.Footnote11

Also in the database are a number of buildings that are possibly aisled, are duplicates, or have been rejected as not being aisled, but are included to avoid confusion. The different structural types and the numbers of examples are listed in , with 2,529 buildings identified as aisled, 75 as possibly aisled, 110 with aisled closed trusses and 173 with spere trusses only (excluding a few late additions to the database; see and ).

Table 1. Types of structureTable Footnote#

Table 2. Types of buildingTable Footnote#

illustrate the types of buildings included in the database, with an aisled hall, a barn, a ruined monastic hospital, an aisled closed truss and the spere truss of a major timber-framed hall without other aisled features.

Figure 4. Aisled spere truss and end truss at West Bromwich Manor, with a central base-cruck truss (1270–88d) (© Bob Meeson)

Figure 5. Spere truss at Rufford Old Hall, Lancashire, late fifteenth century (photo: Francis Franklin, CC BY 4.0)

The maps and most of the statistics examined below (apart from ) are based only on buildings with structural type Aisled; users of the database can decide for themselves how those in the categories of Aisled closed/end truss and Spere truss should treated.

Table 3. Distribution of buildings by county

BUILDING TYPES

lists the types of buildings and the numbers of entries for each type in the database. Of the 2,125 agricultural buildings, the great majority are barns with, in addition, three cowhouses, at Thorncombe, Dorset (detached cow-house), Bobbingworth, Essex (‘out-building used as cowshed’) and Felsted, Essex (outbuilding, possibly a byre with granary over), and one cartshed at Greywell, Hampshire. An interesting small group of barns standing on staddle stones has also been identified; these are considered to be barns, rather than granaries, since they are larger than would be expected for granaries; four are in Hampshire, at Bossington, Michelmersh and Over Wallop (2), with one in Wiltshire, at Allington.

Almost 400 aisled halls have now been identified, compared to 170 in 1986 (of which some were excavated examples, excluded here). One detached aisled kitchen has been recognised (Pevensey, East Sussex).Footnote12 Seven medieval hospitals and nine monastic infirmaries are also included; others probably await identification.

DISTRIBUTIONS AND DATES

It is important in using the database to consider how reliable it is in reflecting both the present-day distribution of aisled buildings and their former existence (which is considered in the concluding section). Among the aisled halls, 57 out of 383 are unlisted, 26 having been demolished; for barns, only 35 (15 demolished) have been added to the 2,087 identified in HEL. Clearly, there is scope for identifying more disguised or fragmentary barns, but it seems very unlikely that many of these would be located away from the present concentrations. Medieval aisled halls have been the subject of intensive research and future work is perhaps more likely to exclude some of the HEL examples, rather than to add to them. Thus, we can have confidence that the database does indeed reflect where aisled buildings are now found.

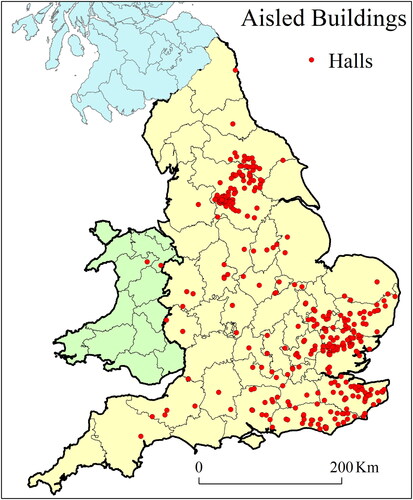

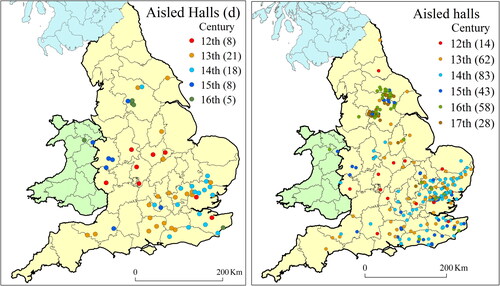

Their distributions by county and by date are summarised in and , and are presented in a more nuanced form in . Aisled halls () are widely distributed, with concentrations in North and West Yorkshire, Essex, Kent and East Sussex. To some extent these must reflect the pattern of fieldwork and further fieldwork might add to the numbers in West rather than East Sussex, but the notable gaps in Lincolnshire, south Essex and Norfolk are surely real. For the last of these we can perhaps suggest a cause: the dominance of the raised-aisle hall, which had perhaps superseded a former aisled tradition by the time that we find numerous surviving buildings. The aisled halls in Yorkshire have been examined by Colum Giles,Footnote13 and he makes it clear that, as the map suggests, the groups in the north and the west are not parts of a continuous distribution, but are distinct. They also differ in the details of their construction.

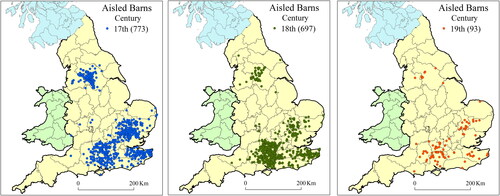

Figure 10. Dates for later aisled barns: (a: left) seventeenth century; (b: centre) eighteenth century; (c: right) nineteenth century

Table 4. Dates of aisled buildingsTable Footnote*

Table 5. Principal upper-roof and purlin types

The rarity of aisled halls in Wales is understandable in the light of the destruction there during the Glyndŵr revolt just after 1400. Almost all of those included in the database have base-cruck or cruck central trusses with either spere trusses (11) or aisled closed trusses (5); documentary evidence suggests that more fully-aisled halls may once have existed.Footnote14

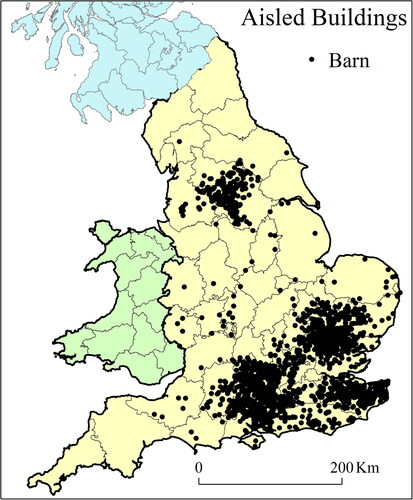

For barns (), Hampshire heads the list, followed by Kent, Essex and West Yorkshire, with all of Berkshire, Cambridgeshire, Hertfordshire and Oxfordshire each also having more than 100 examples; these concentrations are very clear in the mapped overall distribution. It is remarkable how aisled barns hardly exist at all across a great swathe of central England. No aisled barns have been identified in Wales, unsurprisingly perhaps, since they are also almost absent from the adjoining English counties.

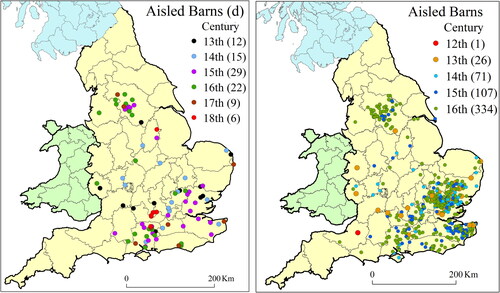

The dates of aisled buildings () also throw light on their distribution. The firmest dating information comes from dendrochronology, with 59 dated halls, ranging from Leicester and Oakham Castles (1137–62d; 1160–85d) to Lands Head Farm, Northowram, West Yorkshire (1580d); the 92 dated barns run from the Barley Barn, Cressing Temple, Essex (1205–30d) to that at Mill Farm, Mapledurham, Oxfordshire of 1742d ().

Datestones are generally assumed to identify construction dates, though they can be misleading and need to be treated with caution. The dates for barns, indeed, do appear mostly to identify the primary phases of the buildings, with the dates often scribed on the posts or tiebeams. However, the handful of such dates for halls, all from West Yorkshire and ranging from 1625 to 1706, relate to the exterior stonework, which may well greatly post-date the aisled structures within these walls.Footnote15 Of the post-1600 dates assigned on stylistic grounds to halls in HEL, almost all also relate to Yorkshire buildings and they are also probably based on the stonework. They raise the same question as do the datestones about whether they properly represent the dates of the original aisled buildings themselves.

For aisled halls (), the earliest, of the twelfth to thirteenth centuries, are scattered across England, unsurprisingly as this was the design of choice for the halls of the greatest in the kingdom. The early infirmaries and hospitals are equally widespread. By the fourteenth century, though, smaller aisled halls are found mainly in the south-east, where they and their derivatives continued to be built, certainly up to about 1500. For the two concentrations of aisled halls in Yorkshire, very few tree-ring dates are known. In West Yorkshire, Broadbottom Old Hall of 1464d is the earliest. The North Yorkshire halls are believed to date generally from the later fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, although the only tree-ring dates we have are much earlier (Felliscliffe (1284d) and Scotton (1342/3d)), suggesting that the existing buildings may well have succeeded predecessors of the same form. It also seems that aisled halls may have continued to be built after 1600 in North Yorkshire, where they developed seamlessly into houses with lean-to outshuts.Footnote16

Similarly, for barns the tree-ring dates up to 1600 differ little from those assigned from typology (), although the ‘sixteenth-century’ barns are much more numerous than the handful of tree-ring dated examples. The single identified twelfth-century aisled barn (the Canon’s Barn, Wells, Somerset) is firmly dated from documents to 1174–6; it has a stone arcade but retains no original timbers.Footnote17 The mapping of later barns () shows clearly how the broader earlier distribution contracts by 1700 onwards to cover only those regions in south-east England where the tradition lasted even well into the nineteenth century.Footnote18 Aisled barns in this region clearly continued to meet agricultural needs. In Yorkshire, small single-aisled barns were built up to around 1800, very often of the ‘laithe-house’ form, attached to the farmhouse.

OTHER INFORMATION

Some additional information that could be extracted straightforwardly from the HEL descriptions is also included in the database. For the building itself, this includes: whether the arcade is of timber or stone; the original and present wall materials; the number of bays (or trusses); whether it has one or two aisles; whether any end aisles are present. Two fields provide information on the roofs above the tiebeams.

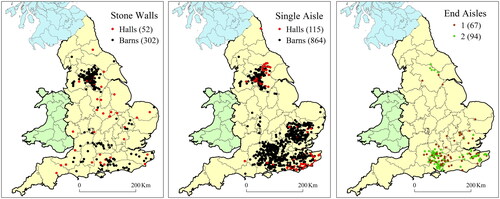

The great majority of the buildings recorded have timber arcades, with only 37 exceptions, mostly in castle halls, hospitals and infirmaries (e.g., ). Similarly, less than 20% have stone outer walls (). Halls with stone walls are widely scattered, mostly in major buildings, while later barns with stone walls are concentrated in northern England. One exceptional building should also be mentioned: the barn at Manor Farm, Buscot, Oxfordshire, built in about 1870, with concrete walls though a timber arcade; it is a notable example of the persistence of the type.Footnote19

The number of bays in the barns gives a measure of their size. The longest aisled building identified is an L-shaped barn at Fifield Manor, Benson, Oxfordshire, of no less than 25 bays, with a second almost as large (20 bays) only a couple of kilometres away; the first has date inscriptions of 1825–7, associated with the Newton family who were farming some 1,700 acres there.Footnote20 Clearly, these barns related to very large arable farming enterprises. Other very long barns are widely scattered in southern England (52 barns with 10 or more bays, from Dorset and Worcestershire to Kent and Suffolk), with four 10–11-bay barns in Yorkshire.

Single-aisled barns and halls represent about a third of those recorded (); the barns are widely distributed, but the halls are concentrated in Yorkshire, Kent and Sussex. shows the scatter of barns with one (67) or two (94) end aisles (sometimes called end outshuts). Apart from a handful in North Yorkshire, these are concentrated in Hampshire and Kent. Six halls with end aisles are recorded, four in Yorkshire and two in Sussex, but exactly what these descriptions correspond to in plan is unclear.

Figure 11. Details in aisled buildings: (a: left) with stone external walls; (b: centre) with a single aisle; (c: right) barns with one or two end aisles

UPPER ROOF FORM

HEL generally describes the upper roofs of aisled buildings and the principal types identified have been encoded in the database, although the reliability of the descriptions is sometimes uncertain. The information is summarised in , with the numbers recorded for halls and barns for each type. It is clear from these figures that the roof types associated with early buildings—crown-posts, passing braces and common-rafter roofs—occur equally in both halls and barns. However post-medieval roof forms—principal rafters, king posts and queen posts, queen struts and raking struts, and also clasped purlins—are overwhelmingly found in barns.

CONCLUSION

The first edition of a database of aisled buildings has been completed, covering principally aisled halls and barns. Its main source in the listed building descriptions will have limited its completeness in three ways. Some buildings that are aisled, particularly much-altered halls, may not have been recognised, fragmentary aisled barns may not have been considered suitable for listing, and demolished buildings are, of course, not in HEL. However, some of the latter have been added from earlier sources, such as Sandell’s 1986 paper. It has also been possible to add buildings discovered during regional fieldwork. Although such a database can never be complete, the process and the numbers identified give a reasonable assurance that it is representative.

The single most striking discovery is perhaps the remarkable number of surviving aisled barns and their exceptional date range. These buildings date from 1170 to 1870: 700 years, with very little differentiation apart from changes in their structural carpentry. The number of aisled halls has also tripled over the number listed in 1986, although others probably still remain to be recognised.

Whether vanished aisled buildings were more widely distributed than their survivors raises questions about the early development of building types that could only usefully be studied by comparing excavation evidence with that from standing buildings. However, this would need to call on entirely different sources of information to those used for the present study. The question therefore has to be left for others to examine, although comparison between the database and excavations would undoubtedly be informative.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Neil Guiden of Historic England was extremely helpful in generating the original searches from the listed building database; Andy Moir worked through the majority of these records to extract the database records. Nick Hill generously shared his information on early aisled halls. Groups and individuals who have reported on aisled buildings in their areas include Colum Giles, Bob Edwards, David and Barbara Martin, John Walker and David Cook for the Yorkshire Vernacular Buildings Study Group. All their help is greatly appreciated.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Smith, “Medieval Roofs,” 133; Sandall, “Aisled Halls in England and Wales,” VA 1975; Sandall, “Aisled Halls in England and Wales,” VA 1976.

2 Ordinary users can carry out such searches, but the results are limited to 1,000 entries, and the information provided with each result is very limited, comprising only the entry name and location, the list number and listing grade, with a link to the full list description, which would have been impossibly cumbersome to have attempted. Fortunately, Neil Guiden at Historic England was able to provide the full information from the HE database, in a form that (with some difficulty) could be converted into a spreadsheet for further processing.

3 Some list descriptions include such confusing phrases (in this context) as ‘an unaisled barn’.

4 By John Walker, David and Barbara Martin and David Cook (from the Yorkshire Vernacular Buildings Study Group records).

5 By the time of publication of this article, the database should be available online at https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archives/view/vag_2019/.

6 Rigold, “The Distribution of Aisled Timber Barns.” This omits most northern aisled barns, as they were originally built with stone walls, and it does not indicate how many barns were plotted, estimated at about 780. Unfortunately, also, no list of the buildings plotted is known to survive.

7 Nick Hill, who has been studying early aisled halls, kindly shared his lists of buildings of these types with me.

8 TNA, C54/55, m. 10; [Calendar] of Close Rolls of the Reign of Henry III, 1242–7 (HMSO, 1916), p. 23. Discussed in Duffy et al., Dublin Castle (Citation2022), 33–5, 274.

9 Giles, “Medieval Aisled Houses in Yorkshire,” 83.

10 E.g., Hornthwaite Farm, Penistone, Yorkshire West Riding (now demolished) (Alcock and Roberts, “Crucks in the North-East and Yorkshire,” 190.]

11 Although the term spere is distinctive, it is rarely obvious from the descriptions if the buildings also contain aisled closed trusses, so some of those listed in this category probably belong with the Aisled closed/end trusses. Wales is an exception to this uncertainty, since the buildings have been fully described by Peter Smith, Houses of the Welsh Countryside.

12 The aisled hall from Newington, Kent, now at the Weald and Downland Museum, West Dean, Sussex has also been identified as a former kitchen or service building.

13 Giles, “Medieval Aisled Houses in Yorkshire.”

14 Suggett, “Crucks in Wales,” 279.

15 Troydale Farm, Pudsey, the latest of these, contains ‘a timbered arcade with 2 large posts on padstones’, which sounds unlikely to be as late as 1706.

16 The handful of post-1600 dates elsewhere probably only indicates the absence of datable features. Thus, Turners, Belchamp St Paul, Essex is dated in HEL as C18 or earlier, but has given a dendro-date of 1329. 40/42 Westhorpe, Southwell, Nottinghamshire (early seventeenth century in HEL) is described as having arch-braced aisle posts and would surely repay further study.

17 Rigold, “The Distribution of Aisled Timber Barns,” refers to ‘great aisled barns with […] stone piers’, but it is not clear what he had in mind, as the Canon’s Barn is the only one identified in the present study.

18 The dates, mostly taken from those given in HEL, should be reasonably reliable for these later buildings.

19 Harvey, Old Farm Buildings, 20, gives details of the building (cited in HEL).

20 Townley, “Benson.”

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Alcock, N. W., and M. W. Barley. “Medieval Roofs with Base-crucks and Short Principals.” Antiquaries Journal 52 (1972): 132–68.

- Alcock, N. W., and M. W. Barley. “Medieval Roofs with Base-crucks and Short Principals: Additional Evidence.” Antiquaries Journal 61, no. 2 (1981): 322–8.

- Alcock, Nat, P. S. Barnwell, and Martin. Cherry, eds. Cruck Building: A Survey. Donington: Shaun Tyas, 2019.

- Alcock, Nat, and Martin Roberts, “Crucks in the North-East and Yorkshire.” In Alcock, Barnwell and Cherry, Cruck Building, 168–91.

- Duffy, S., J. Montague, K. Mulligan, and M. O’Neill. Dublin Castle from Fortress to Palace, I: Vikings to Victorians: A History of Dublin Castle to 1850. Dublin: National Monuments Service, 2022.

- Giles, Colum. “Medieval Aisled Houses in Yorkshire: A Review.” Yorkshire Archaeological Journal 95 (2023): 82–123.

- Harvey, Nigel. Old Farm Buildings. Princes Risborough: Shire Publications, 1975, reprinted 1980.

- Rigold, S. E. “The Distribution of Aisled Timber Barns.” Vernacular Architecture 2 (1971): 20–1.

- Sandall, K. “Aisled Halls in England and Wales.” Vernacular Architecture 6 (1975): 19–27.

- Sandall, K. “Aisled Halls in England and Wales.” Vernacular Architecture 17 (1986): 21–35.

- Smith, J. T. “Medieval Roofs: A Classification.” Archaeological Journal 115 (1958): 112–49.

- Smith, Peter. Houses of the Welsh Countryside. 2nd ed., London: HMSO, 1988.

- Stenning, D. F., D. D. Andrews, and I. Tyers. “Small Aisled Halls in Essex.” Vernacular Architecture 34 (2003): 1–19.

- Suggett, Richard. “Crucks in Wales.” In Alcock, Barnwell and Cherry, Cruck Building, 275–99.

- Townley, Simon, ed. 2016. “Benson (including Fifield, Preston, Crowmarsh, Roke)”, in A History of the County of Oxford, vol. 18. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research, 2016, 21–68. Accessed January 23, 2024. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol18/pp21-68

- Walker, John. “Late-twelfth & Early-thirteenth-century Aisled Buildings: A Comparison.” Vernacular Architecture 30 (1999): 21–53.

APPENDIX:

STRUCTURE OF THE DATABASE

The database has been constructed as an Excel spreadsheet with three sheets:

Database: The full database with the columns given below

Codes: summarising the abbreviations used

Refs: expanding the publication and personal references

lists the principal fields providing information about the buildings; all these are visible in the ADS implementation and most are searchable there. The spreadsheet also contains a few other fields, used for its organisation and processing.

Table 6. Principal database fields