Abstract

The South African government presented its strategy for rolling out vaccinations against Covid–19 in 2021 as a comprehensive plan designed by technocratic experts working with the country’s leading scientists. This imagery built on the government’s prior claims that its responses to Covid over the previous year ‘followed the science’. In 2021, as in 2020, this framing functioned ideologically to justify projects of expanded government control over the economy and the health sector. This article shows how the objective of the vaccination roll-out ‘plan’ was not simply to vaccinate people, but to build key foundations of the proposed ‘national health insurance’ system, including patient registration and procedures for channelling patients (and corresponding financial flows) between public and private health care providers. But the imagery of planned efficiency projected through PowerPoint presentations masked the reality that there was no detailed plan and most of the proposed roll-out scheme was unworkable. We contend, following James Scott, that this was an example of high modernist hubris and aesthetics that confused visual imagery with operational order. Almost every aspect of the supposed vaccination ‘plan’ was subverted, as scientists excluded from government advisory structures disputed aspects of vaccine procurement and use, people ‘walked in’ to vaccination sites where health care workers implemented informal systems to manage them, provincial governments failed to conform with national instructions, and special interest groups lobbied for privileges. The result was that a somewhat disorderly but more effective vaccination roll-out replaced the dysfunctional, overly ordered system set out by government planners.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid–19) had devastating effects in South Africa. By March 2021, a year after the first confirmed case of Covid–19 infection, confirmed cases had reached about 1.5 million, more than 50,000 deaths were officially attributed to Covid–19, while ‘excess deaths’ were running at almost treble this number. Through 2020, the government’s response to Covid–19 had focused on militarised ‘lockdowns’ to reduce inter-personal contact.Footnote1 After the severest lockdowns were relaxed, mask-wearing remained obligatory, large gatherings were banned and sales of alcohol were intermittently restricted or even prohibited. In 2021, the government belatedly prepared for – and, from May, implemented – a mass vaccination programme. This article examines the public planning for, and then initial implementation of, this vaccination programme through the first half of 2021.

The vaccination programme was presented as a continuation of the government’s general response to Covid–19, as being led by ‘the science’. Just as the South African government had sought to employ the legitimacy of science to justify its militarised lockdowns in 2020 at a time when a state of emergency had suspended parliamentary democracy, it invoked the legitimacy of science and technocratic expertise in its presentation of its proposed vaccination roll-out in 2021. The epidemic also facilitated ambitious projects of state expansion. Just as the 2020 lockdowns played into the hands of parts of the state seeking to extend their powers of regulation and surveillance, so the vaccination programme provided an opportunity for state officials to expand the foundations of the government’s proposed national health insurance (NHI) system. As in 2020, the state over-reached. In 2020, economic over-regulation and the killing by police and army of civilians during the repressive enforcement of lockdowns prompted pushback from the public as well as from economic actors. In 2021, the vaccination ‘plan’ was rolled out through the Electronic Vaccine Data System (EVDS) as part of a project to expand surveillance and control of health care provision and financing but was subverted from all sides. In 2021, as in 2020, the state proved to have insufficient administrative capacity to effect its most ambitious schemes, and there proved to be limits to what it could, or was prepared to, achieve through coercion.

This article examines, first, the background to vaccination planning in terms of the discourse and practice of ‘science-led’ policy-making over the preceding year. It then examines the vaccination ‘plan’ itself, focusing on the aesthetics of order set out in the PowerPoint presentations used by officials as a substitute for detailed planning. We contend, following Scott,Footnote2 that the flow charts, maps and diagrams in official presentations were an example of ‘high modernist’ hubris that confused visual order with working order. Officials presented the appearance of technocratic or scientific planning through pinpoint targeting and efficient delivery in anticipation that health care could be re-ordered from the top down, taking advantage of the Covid–19 crisis. We then turn to the subversion of the ‘plan’. Dissenting scientists contested aspects of vaccination procurement and use. Citizens subverted the proposed patient management by ‘walking in’ to sites without appointments or even prior registration. Health care workers in vaccination sites sought to vaccinate people, especially the most vulnerable, as fast as possible and implemented their own local systems for managing patients. Provincial governments had their own preferences and challenges regarding managing the vaccination roll-out. Workers, especially in the public sector, and employers sought to get privileged access to vaccinations. Civil society criticised the national government for its inability to vaccinate people faster. In the face of widespread resistance and clear evidence of administrative over-reach, almost every aspect of the proposed ‘plan’ was jettisoned.

The South African state thus aspired but failed to implement its high modernist ambitions. In his classic work Seeing Like a State, Scott argued that many states ‘see’ their activity in the light of high modernist ideology and a preoccupation with ordering society through rendering the population more ‘legible’ (through practices such as registering births and demarcating cadastral boundaries that create new units of control over citizens and property). Scott showed that such projects of legibility, when combined with ‘high modernist’ schemes to impose ‘scientific’ or rational order on a seemingly disordered and illegible society, could have devastating consequences. He focused primarily on ‘schemes’ implemented by authoritarian or (at best) semi-democratic states, because it was the more authoritarian states that have been better able to suppress resistance (especially from civil society) and impose their preferred order on both the human population and the natural landscape. But Scott also considered capital-intensive agricultural projects in the USA, and his basic idea is relevant to urban and development planning in democratic or semi-democratic settings as well as authoritarian ones.

In the South African case, we argue that the vaccination roll-out rested on a high modernist vision but that, when it came to implementing the roll-out plan, the South African state recoiled from deploying its more authoritarian powers when faced with resistance from civil society (and parts of the state itself). Indeed, in the face of professional and popular resistance – that is, subversion of the plan – state officials abandoned almost every high modernist aspect of their plan. In the end, officials were more committed to the goal of vaccination than they were to their high modernist concern to order this in a particular way.

Scott’s objection to high modernism was not the use of scientific or technical knowledge per se, but rather the refusal to take local knowledge seriously and to substitute aesthetically pleasing representations of order and efficiency in the place of scientific knowledge. Such aesthetics of orderliness, argued Scott, serve as an ‘abbreviated visual image of efficiency’ that is ‘less a scientific proposition to be tested than a quasi-religious faith in a visual sign or representation’.Footnote3 High modernism works ideologically, as Bähre and Lecocq point out, by borrowing ‘the legitimacy of science and technology, without basing its practical implementation on scientific practice’.Footnote4 High modernist schemes fail not only because they prioritise order and control over scientific experimentation but because planners do not appreciate that what might appear to them as disorder – for example a network of winding pathways rather than straight tracks – is often an efficient adaptation to local conditions. When apparent ‘disorder’ is not as irrational as planners assume or imagine, attempts to impose inefficient order are likely to provoke resistance.Footnote5

Scott proposed that high modernist planners, whether in government, development agencies or capitalist corporations, become so enthralled by Cartesian order and so caught in the spell of stylised visions that they develop dangerous ‘blind spots’ and ‘weak peripheral vision’.Footnote6 Scott has been criticised for reifying the state,Footnote7 imputing motivations to plannersFootnote8 and ignoring struggles between different components of the state, but argues that bracketing this aspect of politics was useful in thinking about ‘the way in which a grid of administrative order is imposed over what is, in fact, always a far more complex and disorderly reality’.Footnote9

There is some debate over the extent to which Scott’s concepts can be applied to Africa. Scott presented Nyerere’s Ujamaa villagisation programme as an example of high modernism carried out by a weak state, but he has been criticised for misunderstanding the political context.Footnote10 Scott points to high modernism in colonial development projects, yet Africanists emphasise that colonial power was ‘constantly forced to negotiate with local particularities’.Footnote11 Neither colonial nor most post-colonial African states had the authoritarian power or resources to render their subjects fully legible.Footnote12 The South African state embraced and even innovated technologies of identification and surveillance, but even the apartheid state failed to achieve Verwoerd’s goal of a centralised, comprehensive system of surveillance.Footnote13 While much state surveillance in Africa remains ‘low-tech’,Footnote14 the growing adoption of cellphone technology and electronic banking has strengthened capacity to manage (inter alia) social security payments, including in South Africa.Footnote15 This benefits recipients at the same time as it enhances the capacity of government to control its citizens. In post-apartheid South Africa, the expansion of new township housing can also be understood both as delivering assets to poor people and as a state project of legibility and control, this time in a democratic context.Footnote16

South Africa’s response to Covid–19 was framed by government officials as ‘following the science’ and as ‘best international practice’.Footnote17 The first national lockdown mirrored the strategies adopted across much of Europe, and when the US Food and Drug Administration recommended ‘pausing’ the use of particular vaccines, South Africa was quick to follow. Similar mimicking of so-called ‘best practice’ or ‘cutting edge’ technologies has long been evident in South Africa’s industrial policies.Footnote18 Scott argues that such reaching for putative ‘cosmopolitan universals’ runs the danger of ignoring local conditions and the strategies most suited to them.Footnote19

Scott has observed that the expansion of costly projects of legibility are a ‘near perfect index of the historical and geographical spread of the state’.Footnote20 In South Africa’s case, we argue that the EVDS was employed as an instrument not merely to provide access to essential medicine but to expand state control over health care by using the vaccination programme to start implementing the NHI. While the registration of patients can be considered a modernist project aimed at achieving a modest, desirable level of legibility, the supposed vaccination roll-out plan was a high modernist scheme which sought, unnecessarily given the task at hand, to impose the planners’ preferred re-ordering of access to health care. Like many high modernist schemes, its imposition would be costly. Fortunately, planners reacted quickly to clear evidence of inefficiency and popular (and professional) resistance, saving South Africa from the very costly imposition of high modernism that Scott has described in more authoritarian contexts.

Science and the Covid–19 Lockdown

Faced with Covid–19 in 2020, the South African government professed that its response would be ‘led’ by ‘the science’. This differed sharply from the Mbeki administration’s response to AIDS in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Then, the AIDS denialism of President Mbeki and his health ministers prompted general condemnation from scientists and civil society activists, who campaigned successfully for the expedited public provision of antiretrovirals.Footnote21

In mid March 2020, as the first wave of Covid–19 was tearing through Europe, the South African government declared a ‘national state of disaster’, which gave the state unprecedented regulatory powers, including deploying the army to ensure compliance. People were confined to their place of residence unless they were performing or needing ‘essential’ services. Only those enterprises registered as ‘essential service providers’ were allowed to operate, and those found to be doing so fraudulently were threatened with prosecution. President Ramaphosa justified the lockdown as ‘following the science’ in order to ‘flatten the curve’ of infections. Professor Salim Abdool Karim, an eminent infectious diseases epidemiologist, who chaired the newly appointed Ministerial Advisory Committee (MAC) on Covid–19, was the initial face of this new discourse. He crafted a presentation that outlined the epidemiology of Covid–19 and showed graphs depicting alternative trajectories, which indicated that the lockdown would be lifted when new Covid–19 cases fell below 90 a day.Footnote22 This presentation was shown repeatedly on national television and disseminated widely.

The lockdown affected the economy severely, worsening poverty and inequality.Footnote23 The government had announced a substantial relief package seeking to cushion vulnerable employees against retrenchment and to expand the welfare net through a new Covid–19 social relief of distress grant. These initiatives eventually reached 10 million recipients but were plagued by administrative delays and inefficiencies.Footnote24

Economic devastation and rising poverty forced the government to revise its lockdown strategy even as Covid–19 infections and deaths increased. The initial total lockdown (subsequently labelled ‘level 5’) was relaxed to ‘level 4’ in May 2020, when new cases were running at over three times Karim’s required minimum rate. The country was moved to ‘level 3’ in June 2020, when new infections were growing at almost 20 times that rate. Restrictions on church gatherings were also loosened by level 3 (presumably due to pressure from religious lobbies), prompting comments that this ‘drove a horse and cart through the scientific approach to the pandemic’.Footnote25

The pretence of scientific management of policy was in tatters, yet government planners sought to maintain tight technocratic control. Each change in lockdown level required new planning directives. During the month of May alone, the government issued 44 directives governing (inter alia) transport, services, retail, production and the movement of people.Footnote26 The state sought to micro-manage both the economy and society. On 12 May 2020, for example, the minister of trade, industry and competition, Ebrahim Patel, issued a directive on precisely what kinds of shoes (for example, closed toed shoes) and clothing (for example, winter clothing, baby clothing) could be produced and sold. The president of the Medical Research Council (and MAC member), Glenda Gray, pointed out that none of this could be justified by science, prompting the acting director general in the national Department of Health to accuse her of being out of her ‘jurisdiction’Footnote27 and to call on the Council to discipline her.

Minister Patel, a long-time enthusiast for development planning, saw Covid–19 as an opportunity for more interventionist policies. He told parliament that South Africa ‘cannot go back to a pre-Covid economy’ and that new industrial policies were necessary.Footnote28 Yet, as critics pointed out, his approach came uncomfortably close to a ‘Soviet-style planned economy where the state is charged with trying to ensure an alignment between productive supply from sectors on the one hand, and distribution of products to citizens on the other’ and thus was likely to cause frustration, inefficiency and non-compliance.Footnote29 Such predictions proved correct, and Patel was forced to curtail his ambitions. When lockdown levels were raised during South Africa’s second and third waves of Covid–19 infections, enterprises were simply required to follow Covid–19 protocols. Curfews and restrictions were limited to alcohol sales and restaurants.

While the deployment of the army expanded the state’s coercive power, the state lacked the capacity to implement many of its relief measures. The massive national school and pre-school feeding programmes were suspended, and it was left to civil society to try to deliver food to growing numbers of hungry South Africans.Footnote30 The provision of emergency social grants was delayed, due in part to difficulties in co-ordinating data systems in different parts of the state. Emergency unemployment insurance was rolled out only when business and organised labour intervened, sidestepping incompetent state officials.Footnote31 The auditor-general released a damning ‘citizen’s report’ on how the state had failed the poor. It found that much of the emergency budget allocated for public works programmes, food parcels, support for businesses and emergency services had not been spent owing to ‘an already compromised control environment, often characterised by poor financial management and record keeping, inadequate planning, execution without oversight, leadership instability, lack of coordination across government and poor relations between government departments’.Footnote32

South Africa’s endemic problem of corruptionFootnote33 also raised its ugly head. The Covid–19 epidemic coincided with the (Zondo) Commission of Inquiry into Allegations of State Capture, which sat from 2018 into 2021. When the auditor-general revealed evidence of corruption and price gouging in the procurement of personal protective equipment for medical staff, deputy chief justice Zondo called this ‘frightening’ and lamented the lack of corruption prosecutions.Footnote34 The Zondo Commission was broadcast on national television and probably contributed to rising anger over Covid–19-related corruption and associated pressure on the state to act. The provincial minister for health in Gauteng was dismissed after an investigation. The national minister of health (Mkhize) was later placed on ‘special leave’ and subsequently resigned over the awarding of an over-priced contract for communication services to a company that appeared to have provided kickbacks to his family.Footnote35

The state was roundly criticised by civil society with respect to just about every dimension of public policy in response to Covid–19. Civil society organisations took the government to court to secure the re-opening of school and pre-school feeding schemes. The emergency relief was criticised for being too little, too late. Aspects of the lockdown were criticised by medical scientists, including members of the MAC. In September 2020, Gray and other dissenting members of the MAC – two of whom had chaired MAC sub-committees – were dropped from the MAC. None of these dissidents was appointed to the new specialised vaccine MAC (VMAC). A government determined to wrap itself in the legitimacy of science seemed unable to tolerate open dissent from within its advisory councils. Prominent medical scientists formed a ‘Scientists’ Collective’, which published a series of articles, including – in January 2021 – one that was strongly critical of the government’s inept vaccine procurement (and the complicity in this of the new VMAC). The ‘stunning reality’, they wrote, was that South Africa had neither ‘a secured vaccine supply nor a plan for mass inoculation in the foreseeable future’.Footnote36

National Health Insurance and the Vaccination Roll-Out

South Africa’s ruling party – the African National Congress (ANC) – has long imagined bringing the country’s private health care system under public control to fund improved health care through redistribution from the rich. The ANC had promised in its 2009 election manifesto to implement an NHI, but the practicalities of doing this proved difficult, not least because of ongoing weaknesses in the public health sector. A ‘Green Paper’ was published in 2011 for discussion; a ‘White Paper’ was eventually published at the end of 2015Footnote37 and an NHI Bill was tabled in parliament in late 2019. The parliamentary Portfolio Committee on Health invited written submissions and held public consultations around South Africa in late 2019, but only in May 2021 did the Portfolio Committee finally commence public hearings. The vaccine roll-out thus occurred in the context of ongoing deliberation over the proposed NHI.Footnote38

The NHI Bill sought to provide a ‘single framework’ for the public funding and purchasing of health care services but specified few details of this framework. It listed, in vague terms, the principles and institutional requirements necessary to guide a progressive centralisation of health care under the control of various public boards and bodies. Tax breaks for private medical insurance were to be eliminated, and the size and importance of private health care services reduced over time. But there was no explanation of how the NHI was to be funded, how the quality of health care was to be assessed, how the systemic weaknesses in the public health sector would be addressed nor how private providers were to be compensated or even the time frame for implementation.Footnote39

Dr Nicholas Crisp, the deputy director general in the national Department of Health, in charge of the NHI, was flippant about these challenges and the absence of clear plans. ‘How long is this going to take?’, he asked;

the answer is a long time … We don’t know all the details of what it will look like in the end. What we do know is we are going to have to be flexible. What is it going to cost? It’s going to cost as much as we can afford.Footnote40

The NHI was thus presented as a largely plan-free work in progress to be run by technocrats in a controlling but flexible manner. Given the obvious and persistent weaknesses in the public health care sector, private sector provision was likely to remain important for the foreseeable future. This became even clearer in 2020–21, when private hospitals played central and indispensable roles in the provision of health care to people sick with Covid–19. Any NHI roll-out would thus necessarily require practical mechanisms to allocate patients and payments between private and public health care providers.

The national Department of Health had previously built a partially functioning ‘Health Patient Registration System’ within the public health sector. The Covid–19 vaccination roll-out provided the department with an opportunity to extend registration into the private sector through a new online patient register, the EVDS, that built on systems that were already in place. This and the repurposed ‘stock visibility system’Footnote41 were presented as major steps towards the ‘digital backbone’ for an NHI.Footnote42 None of this was immediately necessary for vaccinating the population. Large-scale vaccination against childhood diseases has long been conducted without prior registration or centrally allocated vaccination appointments.Footnote43 The EVDS ‘ecosystem’ was presented explicitly as going beyond the vaccination drive to pave the way for the NHI. As minister Mkhize put it, the EVDS was integral to the ‘implementation of the National Health Insurance’. It was:

… a significant milestone not only for our vaccination campaign but for South Africa’s advancement towards Universal Health Coverage: This is the first time in our democratic history that a major public health campaign will be supported by one digital system for all South Africans … there will be no distinction between private and state health care users, with the exception that private health care users will input their medical aid details. The quality of services will be the same for all of us and the system will assign a vaccination site closest to our homes or where we work – not based on whether a particular site is a public or private facility. This system is therefore a proud representation of the future of health care in this country, under the NHI …Footnote44

Integrated electronic patient data management systems are projects of legibility with the potential to improve health care.Footnote45 The EVDS raised some issues of patient confidentiality,Footnote46 but most observers welcomed attempts to strengthen electronic record-keeping. The flaws in the vaccination programme did not concern the EVDS per se, but rather the uses to which it was put – that is, the procedures that were attached to it. The Department of Health’s presentations to parliament and in televised press conferencesFootnote47 made it clear that the EVDS would promote and build the NHI by registering and directing patients to accredited health care providers. In contrast to Mkhize’s reassurances that people would be allocated to the most convenient sites, planners sought to use the EVDS to channel insured people to private sites.

The framing of vaccination planning in terms of the NHI reflected the organisational dynamics of the national Department of Health as well as a more pervasive high modernism. In late 2020 and early 2021, the department was hamstrung by vacancies in senior positions, scandals over corruption in the procurement of protective clothing and then a new scandal that surrounded the minister himself. It is possible that the vaccination roll-out was planned in terms of the proposed NHI in part for pragmatic reasons, as the official in charge of NHI planning was the only senior official with the time and inclination to assume the lead – and then frame the roll-out in terms of the NHI.

Scott accepted that ‘large-scale, Modernist schemes of imperative co-ordination’ minutely controlled by a few experts might be the most efficient and equitable response to managing epidemics but warned that such schemes will ‘run into trouble’ when they fail to comprehend social realities and likely social resistance.Footnote48 The South African government’s vaccine roll-out ‘plan’ ran into such predictable trouble, as we shall see below, when people, health care workers and provincial governments resisted the national government’s attempt at imperative co-ordination. This resistance – and the national government’s ensuing abandonment of many aspects of its ‘plan’ – allowed vaccinations to accelerate through the first two months of the roll-out.

The Vaccination ‘Plan’

The government’s vaccination roll-out ‘plan’ was presented – and developed – in a series of PowerPoint slide presentations to the parliamentary Portfolio Committee and televised news briefings. The slides contained colourful diagrams, including maps marked with arrows and supply-chain icons. Additional information and instructions were provided in ‘toolkits’ for sub-national policy makers and vaccination sites.Footnote49 No assessments of the feasibility or cost of these ‘plans’ and instructions were made public. Officials in the Department of Health and the Treasury apparently engaged in some costing exercises in mid 2020, but there appears to have been no systematic planning beyond this for an actual vaccination roll-out. Instead, the planning appears to have taken the form of visual representations of orderly delivery in the hope that people and the vaccination sites would comply with their instructions and related efforts at imperative co-ordination.

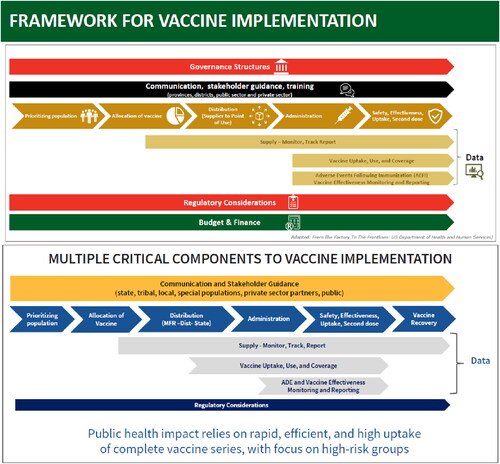

, from a February 2021 presentation by the national Department of Health for the parliamentary Portfolio Committee on Health, reveals a strong Cartesian aesthetic. The slide is an acknowledged adaptation of a diagram in a US vaccine planning document outlining the working strategy for distributing a potential Covid–19 vaccine.Footnote50 The South African ‘framework’ goes further by adding ‘Governance Structures’ at the top, and ‘Budget and Finance’ below. South African government planners appear to have been much more concerned than the USA to control the implementation from the centre. Both indicated the importance of electronic monitoring systems, but whereas the US government did not require prior population registration, the South African government did.

Figure 1. The South African vaccine framework (top panel – source: K. Jamaloodien, ‘Covid-19 Vaccine Rollout’, SAHPRA webinar, 29 March 2021, available at https://path.ent.box.com/s/ogeuosg4hwdsdwptlew8los33jk3xiin, retrieved 20 August 2021) and its US inspiration (bottom panel – source: USDHSS, ‘From the Factory’).

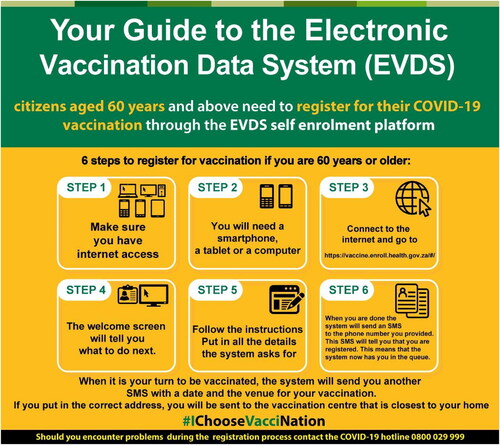

The South African EVDS was at the centre of that ambition. The initial vision was that the EVDS would be pre-populated with data from other databases (including the public payroll and South African Social Security Agency databases). It would record what vaccines had been administered to each recipient, what (if any) side effects ensued and (through linkage to other databases) whether recipients subsequently tested positive for Covid–19.Footnote51 To receive a vaccination, citizens would have to register on the EVDS and then wait for instructions as to where and when they could be vaccinated. Registration required access to the internet, a smartphone and familiarity with navigating online screens (see ). Planners thus appeared to have developed a blind spot in failing to accommodate those without such access,Footnote52 thereby replicating some of the flaws of the registration system for emergency social grants the previous year.Footnote53

Figure 2. The Electronic Vaccine Data System’s registration process. (https://sacoronavirus.co.za/2021/04/16/your-guide-to-the-electronic-vaccination-data-system-evds/)

The national Department of Health allowed some flexibility by allowing sites to register people and slip them into the queue,Footnote54 but this was not communicated to the public. When general registration (and then vaccination) commenced, many officials at national and provincial levels insisted that people would be vaccinated only by prior appointment, scheduled through the EVDS. In the Western Cape, for example, the provincial premier advised people that their appointments might be scheduled for two or even three weeks after initial registration and reminded them that ‘it is very important to remember that you should not visit a vaccination site unless you have been invited to come for your vaccine’.Footnote55 On the eve of public vaccination, the minister of health (Mkhize) advised that anyone who missed their scheduled appointment would be rescheduled but people would not be rescheduled after missing three appointments. The system would allow the roll-out in an organised manner: ‘[t]he programme has been organised to avoid long queues’.Footnote56

The EVDS would be used to control who could be vaccinated through a prioritisation system. The ‘plan’ set out three phases. Health care workers would be covered in the first phase. Phase 2 would target five million people aged 60 and above, eight million people with co-morbidities (such as diabetes), 2.5 million ‘essential workers’ and 1.1 million people in congregate settings such as old-age homes and prisons.Footnote57 The EVDS was piloted among health care workers between February and May 2021 in what was later labelled ‘Phase 1’. After delays in the procurement of vaccines, Phase 2 was set to commence on 17 May 2021 for those over 60 and for health care workers who had not been vaccinated in Phase 1. Selected categories of essential workers would be vaccinated from 1 June. Thereafter, vaccination would be opened to successive age cohorts: people in their 50s from mid July, people in their 40s from September and any adult from mid October.

The logic of the EVDS system required a revision to the initial prioritisation of people with co-morbidities. Planners initially envisaged that those with co-morbidities would be one half of the Phase 2 population, but the EVDS system could not facilitate this. The EVDS could easily verify the age of people seeking to register for vaccination because the first six digits of the South African identity number record a person’s date of birth. But the lack of any existing operational patient register meant that the national Department of Health had no idea who had co-morbidities. Many people with co-morbidities could be identified because they required chronic medicine (such as antiretrovirals for people with AIDS) or had recent in-hospital treatment (for cancer, for example). But the national Department of Health was unwilling to trust medical aid schemes, hospitals and doctors, or even provincial government health management systems to identify people correctly – and the national planners were clearly unwilling to allow people to self-identify on the EVDS as having co-morbidities or even bring appropriate documentation to the vaccination site. Centralised and standardised control through the EVDS meant that vaccination sites and provincial governments were denied discretion and flexibility in this regard. Co-morbidity was dropped from the criteria for eligibility.

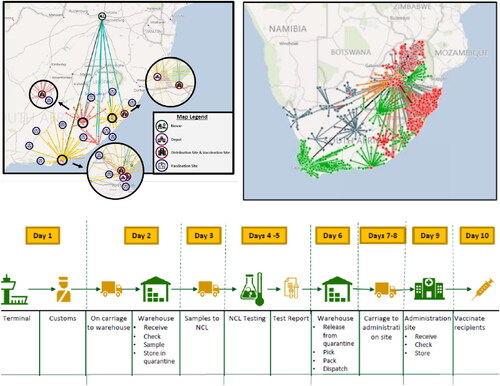

Vaccinations were to be organised primarily by provincial health departments with some support from the private sector (private hospitals and clinics, pharmacies) and employers. Vaccine supplies would be managed centrally and delivered either to provincial depots for onward distribution or directly to the actual vaccination sites. Slides in the presentations showed, in technicolour, the proposed distribution pathways (see ).

Figure 3. The Aesthetics of South Africa’s February 2021 vaccine plan (top left and bottom images – source: Department of Health, ‘Covid-19 Vaccine Rollout Presentation to the Portfolio Committee on Health’, Department of Health of South Africa, 5 February 2021, available at https://sacoronavirus.co.za/2021/02/05/covid-19-vaccine-roll-out-presentation-to-the-portfolio-committee-on-health-5-february-2021/, retrieved 19 August 2021; top right image – source: Jamaloodien, ‘Covid-19 Vaccine Rollout’).

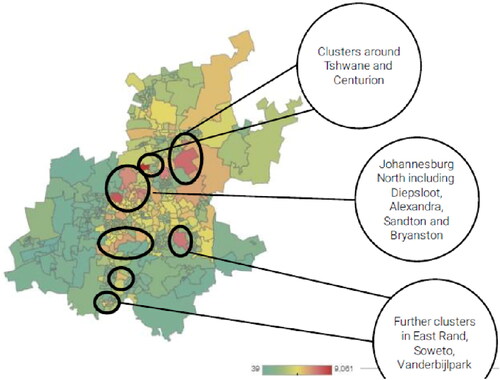

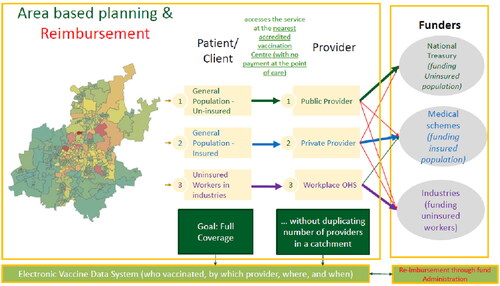

The PowerPoint presentations suggested that the volume of vaccine required in different sites could be gauged precisely. Geocoding enabled the Department of Health to present this in the form of brightly coloured maps identifying the principal locations of elderly people (see ). , from a national Department of Health presentation to the Portfolio Committee on Health in April 2021 is revealing of how the EVDS and related systems were to be used to channel people and payments between public and private providers. According to the 2017 general household survey, 17 per cent of South Africans have private insurance.Footnote58 According to , these people would be channelled to private sector sites (private hospitals and pharmacies) at the expense of their medical aid schemes. Workers who were not insured would be vaccinated at the workplace through an occupational health and safety (OHS) service at the expense of their employers. The vaccination of the uninsured, non-working population would be charged to the National Treasury. The vaccination programme was thus designed not merely to deliver vaccinations but also to pilot and start shaping new relationships between the public and private health sectors.

Figure 4. Spatial identification of concentrations of the elderly in Gauteng province. (Source: National Department of Health, ‘Update on Covid-19’, 30 March 2021)

Figure 5. The EVDS as a mechanism for controlling the flow of people and funding between public and private health facilities. (Source: Department of Health, ‘Update on Covid-19’, 14 April 2021, available at https://sacoronavirus.co.za/2021/04/14/update-on-covid-19-14th-april-2021/, retrieved 19 August 2021)

Planners sought control of every aspect of the vaccination roll-out: from the arrival of the vaccines at the airport to determining who would get vaccinated, when and where and instructing people and vaccination sites to follow their instructions. As Scott would have predicted, it proved unworkable. Every major aspect of the ‘plan’ was subverted and then abandoned.

The Subversion of the ‘Plan’ from Below

The aesthetics of the ‘plan’ evoked the precision and legitimacy of ‘science’. As with the imposition of lockdown in early 2020, the vaccination roll-out in 2021 was presented by ‘experts’ as scientific rather than political. From the outset, however, the claim that policy was led by the science quickly proved fragile as leading scientists continued to criticise one or other aspect of government policy.

Four days before the first version of the ‘plan’ was unveiled in January 2021, the first million doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine had arrived in the country. Soon after, a South African study suggested that the vaccine was probably ineffective among young people in preventing new infections from the so-called ‘South African’ or ‘Beta’ variant.Footnote59 The government decided not to use the vaccine, claiming (again) that it was ‘following the science’. In so doing, it heeded the advice of the controversial head of its VMACFootnote60 and ignored the protests of the lead authors of the study, together with other scientists, who pointed out that the AstraZeneca vaccine (like other approved Covid–19 vaccines) offered protection against serious illness and should therefore be offered to high-risk individuals.Footnote61 The episode revealed how ‘science’ is far from the incontestable ‘truth’ or certainty portrayed in government statements. Tragically, it was later shown that the AstraZeneca vaccine was effective against the Covid–19 variants that drove the third wave of infections in mid 2021, prompting the government to re-introduce AstraZeneca.Footnote62

The government’s sale of the AstraZeneca vaccine left it without any vaccines. It was left to independent researchers led by Gray to secure surplus Johnson and Johnson (J&J) vaccines from trials in the USA and Europe. Their Sisonke ‘trial’ proceeded to vaccinate almost half a million health care workers (and selected others, including the president and the minister of health).Footnote63 In early May, the government finally began to receive consignments of the Pfizer vaccine. Having appropriated the Sisonke trial as ‘Phase 1’ of its vaccination roll-out, the government launched ‘Phase 2’ in mid May using the Pfizer vaccine.

The ‘plan’ was immediately subverted. The plan envisaged the vaccination of any remaining unvaccinated health care workers as well as the elderly. Both categories of people could register through the EVDS. But the EVDS lacked the capacity to validate the self-registration of health care workers. Under Sisonke, a wide range of health care workers (including administrators and researchers) had been able to register and were then vaccinated on production of a confirmatory letter from their employer. When reports surfaced of people who were not front-line health care workers being vaccinated,Footnote64 officials redesigned the EVDS interface to restrict registration to the elderly. Any health care workers still to be vaccinated had to register through a separate electronic platform, where their data could be ‘verified’ through linked public sector employment databases or through health council registration numbers.

The elderly themselves soon began to subvert the ‘plan’. The EVDS initially scheduled appointments for some people in faraway or unfamiliar sites, even requiring several hours of travel,Footnote65 ostensibly because of an initial shortage of vaccination sites and possibly also difficulties in identifying addresses. Some – later many – elderly people decided the system was ‘not working’ and started to walk in to public sites that were known via the proverbial grapevine to be vaccinating elderly people irrespective of whether or not they had an official EVDS appointment.Footnote66 Such local level innovation and preparedness to work around government regulations was not unique to Covid–19 vaccination; it is consistent with longer-standing informal systems of sharing medicines between clinics that developed in preference to engaging with time-consuming government stock management systems.Footnote67

The subversion of the appointments system was accelerated by provincial governments also. Public health facilities are operated by provincial governments, and several resisted the imperative co-ordination from the centre. In the first week of ‘Phase 2’, provincial governments demanded and took control of appointment scheduling from the national Department of Health. Gauteng province pre-emptively announced that anyone already registered on the EVDS could walk into any vaccination site without an appointment and get vaccinated. National government planners initially objected to the way the public was ‘breaking’ the system,Footnote68 but the national government lacked the power to insist that vaccinations be limited to people with scheduled appointments. As the numbers of ‘walk-ins’ grew, so provincial governments and sites turned their attention to ways to manage rather than prohibit this. Walk-ins sometimes resulted in long queues, but social and mainstream media stories highlighted how good-natured people were, how queuing was reminiscent of the first democratic elections in 1994 and how welcoming health care workers were. Sites developed their own signage, some put out chairs, and some nurses reportedly sang happy birthday to people arriving on their birthday. Frail elderly people were typically moved to the front of the queue without anyone else apparently minding.Footnote69

Vaccination sites were thus ordered through a combination of proactive action by local officials and spontaneous popular action in ways that prioritised the needs of the eldest and that the EVDS had failed to do. Scott would not be surprised. In Australia, where people needed to find and make vaccination appointments at sites themselves, different forms of spontaneously mediated order have emerged, such as a website created by a software engineer in Sydney that collates information about vaccine queues and alerts people about vacancies.Footnote70

Registered walk-ins (registered but without scheduled appointments) were soon followed by unregistered walk-ins. The planners had at times conceded that some people would require assistance with registration.Footnote71 It soon became clear that many elderly people, especially in rural areas, lacked effective access to the appropriate technology.Footnote72 Vaccination sites began to assist them to register at nearby facilities (such as public libraries) or on site.Footnote73 Some sites recorded vaccinations on informal paper-based systems and then later ‘uploaded’ the information on to the EVDS. When provincial governments vaccinated people in old-age homes and other congregate settings, they generally uploaded registration details after vaccination. This undermined real-time legibility, and the national Department of Health had to include a disclaimer on its website stating that reported vaccinations did not immediately include those ‘captured on paper’.Footnote74

South African planners eventually accepted walk-ins as official policy, not only because they were forced to do so by the reality on the ground but also because they recognised that walk-ins were driving a roll-out that was otherwise proving disappointingly slow. There were growing calls to abandon the appointment system.Footnote75 Government officials claimed that the slow pace of vaccination was due to a global shortage of vaccinesFootnote76 and that vaccine doses were trapped in a pipeline of necessary controls and checks.Footnote77 Such claims, however, were political theatre, because the supply of vaccines in the country consistently exceeded the number of vaccinations. By mid June 2021, over 4 million vaccine doses had been delivered to the country, yet only 2 million vaccines had been administered; by mid August, more than 20 million doses had been delivered yet only 9 million of these doses had been administered.Footnote78

Government was unforthcoming about the location of the unused vaccine.Footnote79 Some provinces, notably the Western Cape, which hosted an impressive vaccination monitoring ‘dashboard’Footnote80 and provided weekly press briefings on the pace of vaccination and availability of supply, appear to have been genuinely supply-constrained in that they would have been able to vaccinate more people if they had been provided with more vaccine from warehouses under national government control. It is likely that national government planners were using the supply chain processes they controlled to ration vaccines and perhaps to keep them for favoured workplace programmes. They might also have been delaying allocating vaccines to sites owing to concerns about corruption and mismanagement. The 10-day supply chain represented in was probably both a modernist depiction of an unnecessarily long delivery pipeline and a mechanism for control. Unused vaccine was probably also accumulating in sites in less efficient provinces such as the Eastern CapeFootnote81 and in workplace programmes (discussed further below). It is possible that some private sector sites (including private hospitals, care facilities and pharmacies) were able to use their stocks faster than others, but it is also possible that some of this vaccine was lost through theft and corruption. During the political disturbances in July 2021 (after ex-President Zuma was jailed for contempt of court for failing to testify before the Zondo Commission), about 47,000 doses were lost in looting.Footnote82

The inability to use all available vaccine doses, together with mounting public pressure for a faster vaccine roll-out, appears to have prompted the government to open the EVDS for registration of those aged 50 and above from 1 July, even though fewer than a quarter of those aged 60 and above had been vaccinated. The government announced that the EVDS would schedule appointments from mid July, but many people simply followed the established pattern of walking in to vaccination sites. The government eventually conceded this reality, announcing that even private sector sites could vaccinate anyone and that they would be reimbursed subsequently rather than via the system. In mid July, vaccinations were opened to those aged 35 and above, and, from late August, anyone over the age of 18 could get vaccinated. The attempt to regulate and control had finally given way to ensuring that as many jabs got into arms as fast as possible.

The EVDS, with its emphasis on accredited sites, was poorly designed to ensure access for people in rural areas. Some provinces with predominantly rural populations (such as Limpopo) took extra steps to reach elderly people living in remote areas.Footnote83 Limpopo province contested the national requirement for fixed accredited sites. They instead instituted a ‘hub and spoke’ model, in which mobile teams moved between sites and community health workers paid home visits to the elderly, where they registered and vaccinated them, and provided vaccinations at sports events and so on.Footnote84 In reflecting on Limpopo’s ‘best practice’ vaccination, the provincial deputy director general of health care services emphasised the importance of understanding the local context, bringing in local and traditional leaders, churches and ‘influencers’ and otherwise doing what makes sense for the area – including vaccinating on Saturday.Footnote85 Scott would approve.

The task of rural vaccination in places like Limpopo was complicated by the national decision to allocate the first 1.5 million doses of J&J vaccine to occupational programmes. It would have made more sense to allocate this single-dose vaccine to the kinds of outreach programmes being run by Limpopo.Footnote86 The decision to prioritise instead workplace programmes and particular groups of public sector workers, we suggest, reflected an increasingly politicised nature of the vaccination roll-out that further undermined technocratic planning.

The original vaccination plan envisaged that ‘essential’ workers would get vaccinated as a priority group, but no details were provided as to what that meant in practice and when essential workers would be reached. The Sisonke trial de facto prioritised health care workers, and the national roll-out prioritised the elderly. Prioritisation of workplaces was ultimately left to the political arena. At a media briefing in mid June 2021, the national Department of Health revealed that consultations had taken place with trade unions in the National Economic, Development and Labour Council over priority workplaces. Pilot workplace schemes had either already begun or were due to begin soon in mining, manufacturing, the public sector, the taxi industry and in state-owned enterprises.Footnote87 When J&J doses became available, they were earmarked specifically for school teachers, the police and army.Footnote88

Epidemiologically sound arguments can be made for vaccinating workers such as teachers, taxi drivers and police, as they come into regular contact with members of the public. Yet this could apply equally to other occupations such as supermarket cashiers, or to schoolchildren, university professors and university students. But, as Crisp himself admitted, decisions on vaccinations were driven not by scientific concerns as much as by the ‘conflicting demands’ that the Department of Health had to meet.Footnote89 J&J doses that might have been channelled to the rural elderly were instead used – very slowly – to vaccinate unionised workers, mostly in the public sector.Footnote90

By July 2021 – barely six weeks after Phase 2 had commenced – every aspect of the ‘plan’ had been abandoned, in whole or in part. The requirements of prior online registration and appointment scheduling had fallen away – at least for first doses, although EVDS scheduling proved useful for notifying people when they should go for their second doses of the two-dose Pfizer vaccine. Age-based prioritisation had been weakened. Pipeline management, the allocation and monitoring of stock and the system for billing private medical aid schemes appeared to have failed or at least required substantial adjustment.

Conclusion

South Africa’s national vaccination roll-out was characterised by an aspiration for legibility and control, set out in high modernist fashion in a ‘plan’ that promised order but was devoid of detail. In lieu of any actual plan, online presentations were replete with maps, data, flow diagrams and projections. This aesthetic of order proved unworkable in crucial respects. The ‘plan’ was subverted from below, by people demanding vaccination, by health care workers who sought to vaccinate people as fast as possible, aided by provincial governments who did not buy into the national government’s vision of order, and from above, as vaccination was subjected to political pressures from powerful special interest groups.

What proved unworkable was not the modernist project of keeping a register of vaccinations or using geographic information systems and related data to keep track of vaccines and vaccinations. The Western Cape provincial government made good use of such systems to track progress and report back to the public through regular briefings and online. What proved unworkable was the aspiration for centralised management and control. Whereas proactive provinces like the Western Cape and Limpopo sought to monitor and respond to local conditions, the national government’s ‘plan’ sought to use vaccination to re-order and expand control over the entire health care system as part of a wider ambition to institute an NHI. Whereas provincial governments and health care workers at the local level generally sought to vaccinate people as fast as possible, the national government sought to impose its preferred order on the entire operation – even at the cost of slowing the pace of vaccination. It was this ambition to re-order, rather than the EVDS per se, that marked the national government’s ‘plan’ as high modernist.

In Seeing like a State, Scott pointed to the dangers of high modernist hubris in the hands of planners in an authoritarian state. While the South African state deployed considerable coercion in the context of a largely suspended democratic system,Footnote91 it remained accountable in important ways. Government policy was criticised and contested by civil society – including physicians, academics and the media – and by provincial governments and business (less publicly). Government planners retreated in the face of such criticism and in the light of experience. In short, their high modernist hubris was subordinated to their concern to accelerate vaccinations and their recognition of their inability to coerce other state personnel, medical professionals and the public to comply with their initial plan.

In retrospect, the strong demand for vaccination and resistance from below during the first half of 2021 was driven by those willing and able to reach vaccination sites. By the end of June, there were more unused vaccine doses than the total number of vaccine doses administered to date, while less than a third of the elderly had been fully vaccinated. The government rapidly opened vaccinations to younger age groups in July and August. This boosted demand in fits and starts, but fewer than half the adult population had been even partially vaccinated by December. The failure both to mount an effective communications campaign and to ensure easy access to vaccination sites combined with widespread vaccine hesitancy. Raising the vaccination rate would require a combination of effective interventions from above (including clear communications and vaccine mandates) and initiatives on the ground based on local knowledge of local conditions and challenges. While the national Department of Health had made many important concessions to provincial and local realities, it was not clear that it was either willing or able to adapt its approach sufficiently to boost the vaccination rate substantially.

Centre for Social Science Research, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch, Cape Town 7701, South Africa. Email: [email protected]; [email protected]

Notes

1 J. Seekings and N. Nattrass, ‘Covid vs. Democracy: South Africa’s Lockdown Misfire’, Journal of Democracy, 31, 4 (2020), pp. 106–21.

2 J. Scott, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition have Failed (New Haven, Yale University Press, 1998); Two Cheers for Anarchism (Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2012), and ‘Further Reflections on Seeing Like a State’, Polity, 53, 3 (2021), pp. 507–14.

3 Scott, Seeing Like a State, p. 225.

4 E. Bähre and B. Lecocq, ‘The Drama of Development: The Skirmishes behind High Modernist Schemes in Africa’, African Studies, 66, 1 (2007), p. 2.

5 Scott, Seeing Like a State, and Two Cheers for Anarchism.

6 Scott, Seeing Like a State, pp. 290–92.

7 For example, N.R. Smith, ‘Seen Like a State’, Polity, 53, 3 (2021), pp. 485–91; A. Çubukçu, ‘After Seeing Like a State: The Imperialism of Epistemic Claims’, Polity, 53, 3 (2021), pp. 492–7; J.C. Klausen, ‘Seeing Too Much Like a State?’, Polity, 53, 3 (2021), pp. 476–84.

8 For example, L. Schneider, ‘High on Modernity? Explaining the Failings of Tanzanian Villagisation’, African Studies, 66, 1 (2007), pp. 9–38.

9 Scott, ‘Further Reflections’, p. 507.

10 Schneider, ‘High on Modernity?’

11 P. Geschiere, ‘Epilogue: “Seeing Like a State” in Africa – High Modernism, Legibility and Community’, African Studies, 66, 1 (2007), p. 129.

12 Bähre and Lecocq, ‘The Drama of Development’.

13 K. Breckenridge, Biometric State: The Global Politics of Identification and Surveillance in South Africa, 1850 to the Present (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2014). See also D. Posel, ‘The Apartheid Project, 1948–1970’, in R. Ross, A. Mager and B. Nasson (eds), The Cambridge History of South Africa, vol. 2 (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2010), pp. 319–68.

14 K. Donovan, P.M. Frowd and A.K. Martin, ‘ASR Forum on Surveillance in Africa: Politics, Histories, Techniques’, African Studies Review, 59, 2 (2016) pp. 31–7.

15 K. Vincent and T. Cull, ‘Cell Phones, Electronic Delivery Systems and Social Cash Transfers: Recent Evidence and Experiences from Africa’, International Social Security Review, 64, 1 (2011), pp. 37–51; K. Donovan, ‘The Biometric Imaginary: Bureaucratic Technopolitics in Post-Apartheid Welfare’, Journal of Southern African Studies, 41, 4 (2015), pp. 815–33.

16 E. Bähre, ‘Beyond Legibility: Violence, Conflict and Development in a South African Township’, African Studies, 66, 1 (2007), pp. 79–102.

17 This is what officials routinely said in statements, videos and so on. See, for example: President Cyril Ramaphosa, ‘From the Desk of the President’, 4 May 2020 (https://www.thepresidency.gov.za/from-the-desk-of-the-president/desk-president%2C-monday%2C-4-may-2020) and 18th May 2020 (https://mailchi.mp/presidency.gov.za/president-desk-18may20); Cyril Ramaphosa, press conference, 29 September 2021: https://www.sowetanlive.co.za/news/south-africa/2021-09-30-we-are-guided-by-science-ramaphosa-on-ending-state-of-disaster/.

18 N. Nattrass and J. Seekings, Inclusive Dualism: Labour-Intensive Development, Decent Work and Surplus Labour in Southern Africa (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2019).

19 Scott, Two Cheers for Anarchism, and ‘Further Reflections’.

20 Scott, ‘Further Reflections’, p. 514.

21 N. Nattrass, Mortal Combat: The Struggle for Antiretroviral Treatment in South Africa (Pietermaritzburg, University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 2007); N. Geffen, Debunking Delusions: The Inside Story of the Treatment Action Campaign (Johannesburg, Jacana Media, 2010).

22 S.A. Karim, ‘South Africa’s Covid–19 Epidemic: Trends and Next Steps’, e News Channel Africa, Johannesburg (14 April 2020), available at https://www.knowledgehub.org.za/elibrary/sas-covid-19-epidemic-trends-and-next-steps, retrieved 20 August 2021.

23 D. van Seventer, C. Arndt, R. Davies, S. Gabriel, L. Harris and S. Robinson, ‘Recovering from COVID–19: Economic Scenarios for South Africa’, IFPRI Discussion Paper 02033 (July 2021), available at https://www.ifpri.org/publication/recovering-Covid-19-economic-scenarios-south-africa, retrieved 20 August 2021; A. Horn and A. Donaldson, ‘Labour Market Effects of the Great Lockdown in South Africa: Earnings and Employment During 2020-2022’, SALDRU Working Paper 279 (Cape Town, UCT, 2021), available at http://opensaldru.uct.ac.za/handle/11090/1007, retrieved 20 August 2021.

24 J. Seekings, ‘Bold Promises, Constrained Capacity, Stumbling Delivery: The Expansion of Social Grants in Response to the Covid–19 Lockdown in South Africa’, CSSR Working Paper 456 (Cape Town, UCT, 2020), available at http://www.cssr.uct.ac.za/cssr/pub/wp/456, retrieved 20 August 2021; E. Senona, E. Torkelson and W. Zembe-Mkabile, Social Protection in a Time of COVID (Mowbray, Black Sash, 2021), available at http://blacksash.org.za/images/0541_BS_-_Social_Protection_in_a_Time_of_Covid_Final_-_Web.pdf, retrieved 20 August 2021; Horn and Donaldson, ‘Labour Market Effects’.

25 Quoted in J. February, ‘South Africa Will Pay the Price of Ramaphosa’s Folly Regarding Religious Gatherings’, Daily Maverick, Johannesburg, 27 May 2020, available at https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2020-05-27-south-africa-will-pay-the-price-of-ramaphosas-folly-regarding-religious-gatherings/, retrieved 20 August 2021.

26 These can be found at https://www.gov.za/Covid–19/resources/regulations-and-guidelines-coronavirus-Covid–19.

27 See https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=294732601558743, retrieved 25 August 2021.

28 E. Patel, remarks by minister Ebrahim Patel during NCOP debate on government’s response to the Covid pandemic (23 June 2020), available at https://www.gov.za/speeches/remarks-minister-ebrahim-patel-during-ncop-debate-government%E2%80%99s-response-Covid-pandemic-23, retrieved 20 August 2021.

29 M. Morris, ‘An Economic Framework for Reopening Business’, Daily Maverick, 11 May 2020, available at https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2020-05-11-an-economic-framework-for-reopening-businesses/, retrieved 20 August 2021.

30 J. Seekings, ‘Failure to Feed: State, Civil Society and Feeding Schemes in South Africa in the First Three Months of Covid–19 Lockdown, March to June 2020’, CSSR Working Paper 455 (Cape Town, UCT, 2020), available at http://www.cssr.uct.ac.za/cssr/pub/wp/455, retrieved 20 August 2021.

31 Seekings, ‘Bold Promises’.

32 Auditor-General South Africa, Citizen’s Report on the Financial Management of Government’s Covid–19 Initiatives (Pretoria, Auditor General South Africa, 2020), pp. 10–11.

33 I. Chipkin, ‘Making Sense of State Capture in South Africa’, Submission to the State Capture Commission (2021), available at https://www.scribd.com/document/506612384/2021-Making-Sense-of-State-Capture#from_embed, retrieved 19 August 2021.

34 J. Chabalala, ‘Zondo Says PPE Corruption Reports Are “Frightening”, Laments Lack Of Corruption Prosecutions’, News24, Cape Town, 4 September 2020, available at https://www.news24.com/news24/southafrica/news/zondo-says-ppe-corruption-reports-are-frightening-laments-lack-of-corruption-prosecutions-20200904, retrieved 19 August 2021.

35 G. Makhafola, ‘SIU Probe Directly Implicates Mkhize in Digital Vibes Appointment’, News24, 27 June 2021, available at https://www.news24.com/news24/southafrica/news/siu-probe-directly-implicates-mkhize-in-digital-vibes-appointment-report-20210627, retrieved 20 August 2021; E. Ellis, ‘Exposed and Tarnished by the Digital Vibes Scandal, Zweli Mkhize Goes Down Fighting’, Daily Maverick, 6 August 2021, available at https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-08-06-exposed-and-tarnished-by-the-digital-vibes-scandal-zweli-mkhize-goes-down-fighting/, retrieved 20 August 2021.

36 D. Aslam, G. Gray, G. Richards, M. Mendelson, F. Abdullah, F. Venter, J. McIntyre, A. Wulfsohn and A. Van den Heever, ‘Vaccines for South Africa. Now’, Daily Maverick, 2 January 2021, available at https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-01-02-vaccines-for-south-africa-now/, retrieved 19 August 2021.

37 R. van Niekerk, ‘The Politics of Universalising Health Care in South Africa: History, Policy and Institutions’, Transformation, 91 (2016) pp. 40–62.

38 See https://www.parliament.gov.za/project-event-details/54 and https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201908/national-health-insurance-bill-b-11-2019.pdf.

For information on the bill and hearings, see: https://pmg.org.za/blog/NHI:%20Tracking%20the%20bill%20through%20Parliament.

39 See, for example, Helen Suzman Foundation, ‘The National Health Insurance Bill’, submission by the Helen Suzman Foundation to the National Assembly’s Parliamentary Committee on Health, 28 November 2019, available at https://hsf.org.za/publications/submissions/submission-nhi-bill-28-november-2019.pdf, retrieved 20 August 2021.

40 Ibid., p. 7.

41 Department of Health, ‘COVID–19 Implementation Guide and Toolkit’ (20 May 2021), available at http://www.health.fs.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/VACCINE-INTRODUCTION-GUIDE-AND-TOOL-KIT-VERSION-23-MAY-2021.pdf, retrieved 20 August 2021, pp. 25, 56–7.

42 L. Owings, ‘How Safe Is Your Data on the EVDS?’, Spotlight, 7 July 2021, available at https://www.spotlightnsp.co.za/2021/07/07/how-safe-is-your-data-on-the-evds/, retrieved 20 August 2021.

43 D. Ndwandwe, C.A. Nnaji and C.S. Wiysonge, ‘The Magnitude and Determinants of Missed Opportunities for Childhood Vaccination in South Africa’, Vaccines, 8, 4 (2020), p. 705.

44 Z. Mkhize, ‘Opening Remarks: Launch of EVDS Registration for Covid–19 Vaccination’ (16 April 2021), available at https://sacoronavirus.co.za/2021/04/16/opening-remarks-minister-zwelini-mkhize-launch-of-evds-registration-for-covidCovid-19–19-vaccination-citizens-aged-60-and-above/, retrieved 20 August 2021.

45 N. Mostert-Phipps, D. Pottas and M. Korpela, ‘Improving Continuity of Care through the Use of Electronic Records: A South African Perspective’, South African Family Practice, 54, 4 (2012), pp. 326–31.

46 Owings, ‘How Safe Is Your Data’.

47 These are available on https://sacoronavirus.co.za/.

48 Scott, Two Cheers, pp. 36–7.

49 See, for example, Department of Health, ‘COVID–19 Implementation Guide and Toolkit’ (20 May 2021).

50 US Department of Health and Human Services, ‘From the Factory to the Frontlines: The Operation Warp Speed Strategy for Distributing a COVID–19 Vaccine’ (23 September 2020), available at https://www.hsdl.org/?abstract&did=844253, retrieved 20 August 2021.

51 National Department of Health, ‘COVID–19 Response’, presentation (7th January 2021), slide 31.

52 Academy of Science of South Africa, Root Causes of Low Vaccination Coverage and Under-Immunisation in Sub-Saharan Africa (Pretoria, Academy of Science of South Africa, 2021), available at https://research.assaf.org.za/bitstream/handle/20.500.11911/189/2021_assaf_low%20vaccination_under_immunisation%20_consensus.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y, retrieved 19 August 2021.

53 Senona, Torkelson and Zembe-Mkabile, Social Protection.

54 National Department of Health, ‘COVID–19 Implementation’, p. 60.

55 Online media briefings, 13 and 20 May 2021: https://www.facebook.com/windealan/videos/519306882416571 and https://www.facebook.com/watch/live/?v=963313317543072&ref=watch_permalink.

56 Eye Witness News, ‘Health Minister Mkhize on Phase 2 Vaccine Rollout’, 16 May 2021, available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QNzND_6FlGQ, retrieved 22 August 2022.

57 National Department of Health, ‘Update on Covid–19’, Department of Health of South Africa (30 March 2021), available at https://sacoronavirus.co.za/2021/03/30/update-on-Covid–19-30th-march-2021/, retrieved 19 August 2021; Jamaloodien, ‘Covid–19 Vaccine Rollout’.

58 StatsSA, ‘Statistical Release no. PO318, General Household Survey, 2017’ (2018), available at http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0318/P03182017.pdf, retrieved 19 August 2021.

59 S.A. Madhi, V. Baillie, C.L. Cutland, M. Voysey, A.L. Koen, L. Fairlie, S.D. Padayachee, K. Dheda, S.L. Barnabas, Q.E. Bhorat and C. Briner, ‘Efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV–19 Covid–19 Vaccine Against the B. 1.351 Variant’, New England Journal of Medicine, 384, 20 (2021), pp. 1885–98.

60 B. Schoub, ‘Dial Down the Rhetoric Over COVID–19 Vaccines’, South African Medical Journal, 111, 6 (2021), pp. 522–3.

61 W.D.F. Venter, S.A. Madhi, J. Nel, M. Mendelson, A. van den Heever and M. Moshabela, ‘South Africa Should Be Using All the COVID–19 Vaccines Available to It – Urgently’, South African Medical Journal, 111, 5 (2021), pp. 390–92, and ‘COVID–19 Vaccines – Less Obfuscation, More Transparency and Action’, South African Medical Journal, 111, 6 (2021), pp. 515–16.

62 E. Ellis, ‘Oxford/AstraZeneca Vaccine to Make a Comeback and Provide Boost to National Drive’, Daily Maverick, 6 August 2021, available at https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-08-06-oxford-astrazeneca-vaccine-to-make-a-comeback-and-provide-boost-to-national-drive/, retrieved 20 August 2021.

63 C. Bateman, ‘Behind the Scenes: How the First 500,000 Vaccine Doses Administered in SA Were Secured’, Daily Maverick, 17 May 2021, available at https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-05-17-behind-the-scenes-how-the-first-500000-vaccine-doses-administered-in-sa-were-secured/, retrieved 19 August 2021; L. Bekker, G. Gray, A. Goga, N. Garrett, L. Fairall, I. Sanne, F. Mayat, J. Odhiambo and S. Tavuka, ‘The Sisonke Trial Rewrote History: Eight Lessons for The Nationwide Vaccine Rollout’, Daily Maverick, 26 May 2021, available at https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-05-26-the-sisonke-trial-rewrote-history-eight-lessons-for-the-nationwide-vaccine-roll-out/, retrieved 19 August 2021.

64 Independent Online (IOL), Staff Reporter, ‘Cape Man Who Claimed J&J Doses Were Expiring and Got Vaccinated Issues Apology After Uproar’, Independent Online, Cape Town, 14 May 2021, available at https://www.iol.co.za/capeargus/news/cape-man-who-claimed-j-and-j-doses-were-expiring-and-got-vaccinated-issues-apology-after-uproar-f625266b-932b-46b2-9fbd-c3c4dbe79b16, retrieved 20 August 2021; E. Ellis and C. Nortier, ‘Vaccine Cheats: The EVDS Has Not Failed – The Public Has Broken the System’, Daily Maverick, 25 May 2021, available at https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-05-25-vaccine-cheats-the-evds-has-not-failed-the-public-has-broken-the-system/, retrieved 20 August 2021.

65 See T. Cohen, ‘How Does It Feel to Win the Vaccine Lottery? Wonderful, With Tinges of Guilt’, Daily Maverick, 18 May 2021, available at https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2021-05-18-how-does-it-feel-to-win-the-vaccine-lottery-wonderful-with-tinges-of-guilt/, retrieved 19 August 2021; N. Nattrass, ‘How Bending the Rules Is Getting People Vaccinated’, GroundUp, Cape Town, 26 May 2021, available at https://www.groundup.org.za/article/vaccine-rollout-nurse-comes-rescue/, retrieved 20 August 2021.

66 E. Webster, ‘My Vaccine Moment: Seize the Time for a Fundamental Rethinking of Capitalism’, Daily Maverick, 31 May 2021, available at https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-05-31-my-vaccine-moment-seize-the-time-for-a-fundamental-rethinking-of-capitalism/, retrieved 20 August 2021; B. Fitchen, ‘Covid Vaccinations. This Hospital Shows How It Is Done’, GroundUp, 28 May 2021, available at https://www.groundup.org.za/article/one-persons-vaccination-experience-it-was-reminiscent-voting-first-time–1994/, retrieved 19 August 2021.

67 R. Hodes, I. Price, N. Bungane, E. Toska and L. Cluver, ‘How Front-line Healthcare Workers Respond to Stock-outs of Essential Medicines in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa’, South African Medical Journal, 107, 9 (2017), pp. 738–40.

68 Ellis and Nortier, ‘Vaccine Cheats’.

69 Fitchen, ‘Covid Vaccinations’.

70 N. Cave, ‘Locked Down and Fed Up. Australians Find Their Own Ways to Speed Vaccinations’, New York Times, 12 August 2021, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/12/world/australia/Covid-delta-lockdown-vaccination.html?action=click&module=Well&pgtype=Homepage§ion=World%20News, retrieved 19 August 2021.

71 For example, National Department of Health, ‘COVID–19 Implementation’.

72 For example, J. Isaac, ‘Elderly in Rural Eastern Cape Struggle to Register for Vaccines’, GroundUp, 27 May 2021, available at https://www.groundup.org.za/article/elderly-rural-eastern-cape-struggling-register-vaccines/, retrieved 20 August 2021; K. Alexander and B. Xezwi, ‘Simple but Urgent Steps Needed to End Vaccine Inequality Involving South Africa’s Elderly’, Daily Maverick, 30 June 2021, available at https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-06-30-simple-but-urgent-steps-needed-to-end-vaccine-inequality-in-south-africas-elderly/, retrieved 19 August 2021.

73 Nattrass, ‘How Bending the Rules’.

74 See slide 1 on https://sacoronavirus.co.za/latest-vaccine-statistics/, retrieved 25 August 2021.

75 For example, N. Geffen and M. Low, ‘How to Vaccinate Millions As Quickly As Possible’, Daily Maverick, 14 May 2021, available at https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-05-14-how-to-vaccinate-millions-as-quickly-as-possible/, retrieved 20 August 2021.

76 M. Sizani, ‘Elderly People Waited in Vain for Hours for Vaccines at a Gqeberha Site’, GroundUp, 10 August 2021, available at https://www.groundup.org.za/article/elderly-waited-hours-vaccines-gqeberha-site-and-then-received-nothing/, retrieved 20 August 2021; C. Keeton and T. Farber, ‘Vaccine Rollout Stalls As Covid–19 Rages On in South Africa’, Sunday Times, Johannesburg, 8 August 2021, available at https://www.timeslive.co.za/sunday-times/news/2021-08-08-vaccine-rollout-stalls-as-Covid–19-rages-on-in-sa/, retrieved 20 August 2021.

77 P. de Wet, ‘“We Can Never Let The Supply Chain Run Dry”: Why South Africa Never Vaccinates on Sundays’, Business Insider South Africa, Cape Town, 8 June 2021, available at https://www.businessinsider.co.za/no-sunday-vaccinations-in-south-africa-because-of-10-day-pipeline-2021-6, retrieved 19 August 2021.

78 Calculated from data on https://sacoronavirus.co.za/ together with information from the national Department of Health and the national Treasury on vaccine supply shipments.

79 N. Nattrass and J. Seekings, ‘Covid–19: Current Challenge is not the Supply but the Delivery of Available Vaccines’, Daily Maverick, 22 July 2021, available at https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-07-22-Covid–19-current-challenge-is-not-the-supply-but-the-delivery-of-the-available-vaccines/, retrieved 20 August 2021.

81 N. Nattrass and J. Seekings. ‘South Africa’s Vaccine Rollout Needs a Boost’, GroundUp, 27 May 2021, available at https://www.groundup.org.za/article/south-africas-vaccine-rollout-needs-a-boost/, retrieved 20 August 2021.

82 This was announced by the acting minister of health on 23 July 2021 (https://www.enca.com/news/47500-vaccines-lost-or-damaged-looting-kubayi).

83 S. Nyathikazi, ‘Limpopo Jabs Ahead of the Rest With its “Tailor-Made” Covid–19 Vaccination Rollout’, Daily Maverick, 4 July 2021, available at https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-07-04-limpopo-jabs-ahead-of-the-rest-with-its-tailor-made-Covid–19-vaccination-roll-out/, retrieved 20 August 2021.

84 M. Dombo, ‘Limpopo Department of Health COVID–19 Vaccine Rollout Strategy: Best Practice Input. NDOH Virtual Media Briefing: SA Response to COVID–19’ (13 August 2021), available at https://sacoronavirus.co.za/2021/08/13/limpopo-department-of-health-Covid–19-vaccine-rollout-strategy/, retrieved 20 August 2021.

85 Ibid.

86 N. Nattrass and J. Seekings. ‘We Shouldn’t Shift Vaccines Away from the Elderly’, GroundUp, 30 June 2021, available at https://www.groundup.org.za/article/dont-ration-vaccines-away-from-the-elderly/, retrieved 20 August 2021.

87 National Department of Health, ‘Acting Health Minister Leads Virtual Media Briefing on COVID–19 Update and the Vaccination Rollout Plan’, media advisory, 17 June 2021, https://sacoronavirus.co.za/2021/06/17/acting-health-minister-leads-virtual-media-briefing-on-Covid–19-update-and-the-vaccination-rollout-plan/, retrieved 20 August 2021.

88 C. Ramaphosa, ‘President Ramaphosa Moves South Africa to Alert Level 3’, Daily Maverick, 15 June 2021, available at https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-06-15-president-ramaphosa-moves-south-africa-to-alert-level-three/, retrieved 20 August 2021.

89 N. Crisp, ‘Progress on COVID–19 Vaccine Rollout’, eNCA, 8 June 2021, available at https://sacoronavirus.co.za/2021/06/08/enca-discussion-progress-on-Covid–19-vaccine-rollout-dr-nicholas-crisp/, retrieved 19 August 2021.

90 Nattrass and Seekings, ‘Covid–19: Current Challenge’.

91 Seekings and Nattrass, ‘Covid vs. Democracy’.