Abstract

When the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of 1996/97 was tasked with investigating gross human rights violations from 1 March 1960 to 1994, there was a presumption that apartheid atrocities began with the massacre at Sharpeville in which police shot and killed 69 people. That massacre, on 21 March 1960, is also thought to have been the largest single-day mass killing by police in the apartheid era. Research on the African National Congress (ANC) Defiance Campaign of 1952 questions both presumptions. There were numerous clashes between police and protesters that involved extensive police violence but have been remembered as ‘riots’. The worst was in East Bank Location/Duncan Village, East London, on 9 November 1952. Police broke up an ANC Youth League-organised meeting and over the next few hours shot and killed an untold number of people. Estimates of the death toll range from an official figure of eight to more than 200, with two white people killed by enraged crowds in retaliation. Until recently the events were clouded in secrecy. This article draws on the now extensive historiography on the day as well as new archival and field research and international literature on mass killings. It concludes that the police killings on South Africa’s ‘Bloody Sunday’ should be recognised as a massacre that was covered up by both sides.

The police have a strong mandate to drastically suppress clashes between whites and non-whites. They will use their bludgeons where necessary and they will shoot where necessary. (C.R. Swart, Minister of Justice, South Africa, 1 November 1952, eight days before Bloody Sunday)Footnote1

[T]here are hundreds of people whose memories of that night of terror and long agony flatly contradict the official version. (Advance, Cape Town, 27 November 1952)

Introduction

When the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of 1996/97 was tasked with investigating gross human rights violations from 1 March 1960 to 1994, there was a presumption that the National Party’s atrocities began with the massacre at Sharpeville in which police shot and killed 69 people. That massacre, on 21 March 1960, is also thought to have been the largest single-day mass killing by the police in the apartheid era. Research on the African National Congress (ANC) Defiance Campaign of 1952 questions both presumptions. There were numerous instances of extreme police violence during the six-month campaign. Foremost of these was East London’s ‘Bloody Sunday’ on 9 November 1952, at the height of the Defiance Campaign, when relations between police and ANC supporters were at a nadir and anti-white sentiment was rife. In East Bank Location, police dispersed an ANC Youth League-organised meeting and over several hours killed an untold number of black people, while vengeful crowds killed two white people. The police admitted responsibility for eight deaths and 27 injuries but there have long been claims that they killed more than 200 people. The events were clouded in secrecy from the start.

In a previous JSAS article, I discussed the silences surrounding the death of Dr Elsie Quinlan, also known as Sister Aidan Quinlan, who was one of the two white people killed that day. Insurance salesman Barend Vorster was the other.Footnote2 Sister Aidan was an Irish nun and medical doctor who lived and worked at a Catholic mission in Duncan Village, where she ran a popular clinic, and is believed to have encountered the vengeful mob on her way to help the wounded. I have written about the life, death and memorialisation of Sister Aidan in greater depth, and to some extent the police killings that preceded and followed her murder, in my book Bloody Sunday.Footnote3 This article focuses on the black victims and provides an extended account of the police violence through the lens of international research on massacres.

To the extent that the events of 9 November 1952 have been recorded at all, they have gone down in history as ‘riots’, with the emphasis on the crowd’s violence rather than that committed by the police. In this article I argue that the day deserves to be remembered as a day of massacre. I address some of the theoretical and historical literature on massacres before considering the specific circumstances of South Africa’s ‘Bloody Sunday’ and the possibility that the death toll was higher that day than at Sharpeville.Footnote4

I use ‘Duncan Village’ to refer to the ‘location’ (as an area demarcated for black people to live was then called) in which the violence of 9 November 1952 took place. In 1952, East London had three locations, the largest of which was situated on the East Bank of the Buffalo River and consisted of an older, mostly wood and iron shack settlement called East Bank Location and a section with houses recently built by the municipality called Duncan Village, named after the governor-general, Sir Patrick Duncan. By 1952 residents were beginning to call the whole location ‘Duncan Village’ and for this reason I have chosen to use that name when not referring to the East Bank Location area specifically. East Bank Location was destroyed during the forced removals of the 1960s. The remaining area continues to be called Duncan Village.

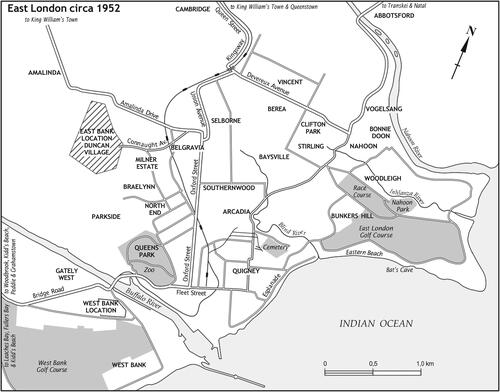

In 1952, East Bank Location/Duncan Village housed more than 40,000 black people on little more than 300 acres, while about 43,000 white people lived in East London on nearly 7,000 acres. The entire location was smaller than their golf course (see ). Barely five kilometres from the centre of East London, but surrounded by bush kept as buffer territory, the location was out of sight and mind of white East London. Whites did not need to go through or past it to get to any destination and few visited it. The police and City Council Native Affairs Department aimed at complete control of the location and harassed its inhabitants mercilessly as they applied the web of laws which applied to black people at the time.

Figure 1. East London circa 1952. (Source: M. Breier, Bloody Sunday: The Nun, the Defiance Campaign and South Africa’s Secret Massacre, Cape Town, Tafelberg, 2021; published with the permission of the publishers.)

I have named 9 November 1952 ‘Bloody Sunday’, but the day is also known as ‘Black Sunday’.Footnote5 Daily Dispatch journalist Jock McFall used ‘Black Sunday’ in his book on Sister Aidan published in 1963 and it has since been repeated.Footnote6 McFall’s pro-police and one-sided version of events discouraged me from using the term. I was also aware of the commercial connotations of ‘black’ days, where the term is used to advertise shopping specials. Hlengiwe Ndlovu (in this Part-Special Issue) refers to the police killings in East London that day as the ‘Bantu Square massacre’, emphasising the site where the meeting was held and the deaths of women who had gathered there to pray. My research shows there were two rounds of police shootings – the first at Bantu Square and the second across the whole location. ‘Bloody Sunday’ aims to encompass both rounds and reflect the resonances between the police killings in Duncan Village and the ‘Bloody Sunday’ massacres of unarmed civilians in international, particularly Irish, history. Sister Aidan was from Cork, Ireland.

It is also important to distinguish between the police violence of 9 November 1952 and that in 1985 which has come to be known as the Duncan Village Massacre. In 1985, running battles between youths and police extended over several days and led to police killing 32 people.Footnote7 Although there was considerable crowd violence in 1985, including the burning of government buildings and councillors’ and policemen’s homes, and mob killings of a black policeman and two white men (in separate incidents), the events have not gone down in history as riots, as they might have done in the 1950s, but are remembered for the police violence.

Theory of Massacre

International literature on massacres provides a useful framework for describing and analysing the events of 9 November 1952. The word ‘massacre’ has its origins in Latin and French, with connotations of bludgeon, butchery and the killing of animals as well as humans. There are many examples of outside forces being utilised to effect a massacre on peoples with whom there are no ties or emotional bonds. But perpetrators and victims might also come from the same community, where victims are stigmatised and seen as less than human. The ‘paranoid polarisation of identity’ of perpetrators and victims is a feature of the societies in which massacres occur and accounts for the consent, whether tacit or explicit, that follows.Footnote8

The killings on 9 November 1952 bear elements of the violent ‘crackdowns’ on minimally violent protest which Alexei Anisin calls ‘protest massacre’, but the propaganda beforehand, the extensive preparations and the secrecy surrounding them indicates the more calculated type of massacre described by Jacques Semelin.Footnote9 Such killings take place in ‘areas that can be sealed off’, where violence may ‘surpass all limits’ and the surrounding population is ‘indifferent or complicit’.Footnote10

Semelin argues that the number of protesters killed is a less important consideration than the brutality of the killings and the ‘asymmetry of the relations of physical force’, to the extent that the perpetrators can undertake the killings without danger to themselves.Footnote11 Anisin’s comparative study of 76 massacres includes fatality tolls as low as 10; in another study the limit is 15.Footnote12 A study of settler massacres in Australia sets a lower limit of six.Footnote13 The vast discrepancy between the official and unofficial death tolls associated with South Africa’s Bloody Sunday are not uncommon. Often the official toll includes only those who died on the day, while many might have succumbed to injuries later. The massacre of the Israelites at Bulhoek, near Queenstown (now Komani), South Africa, in 1921 is one example. Police records put the final total at 225, including 163 people who were killed on the day and 62 who subsequently died of their wounds.Footnote14

Often the official figures are a gross underestimation designed to downplay a situation where the forces were out of control or excessively brutal and authorities need to maintain an image of justified enforcement of law and order. International examples include the ‘race riot’ in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1921 which took place over two days and led to the destruction of the city’s thriving ‘Black Wall Street’. The Tulsa massacre, as it is now known, had an initial official death toll of nine white and 26 black people. A commission in 2001 found that ‘considerable evidence exists to suggest that at least seventy-five to one-hundred people, both black and white, were killed during the riot’, while the director of relief operations of the American Red Cross in Tulsa following the events reported that ‘the total number of riot fatalities may have ran as high as three-hundred’.Footnote15

The unreliability of both state figures and eyewitness accounts is illustrated in literature on the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in Amritsar, Punjab, in 1919.Footnote16 Crowd estimates have ranged from 5,000 to 30,000, with eyewitnesses asserting that 1,000 people were killed. While such a death toll was possible, given that the police shot 1,650 bullets over ten minutes, counts of the names of victims range from 379, set by the colonial police, to 574, established in a museum research project many decades later.Footnote17 In South Africa, Philip Frankel suggests a higher toll at Sharpeville than the official and ever-quoted figure of 69, citing the truckloads of bodies that were buried secretly to hide their extraordinary wounds from dumdum bullets.Footnote18

The Defiance Campaign and its Demise

The Bloody Sunday massacre in Duncan Village took place at the height of the ANC’s Campaign of Defiance against Unjust Laws. Launched on 26 June 1952, the campaign was a response to the plethora of discriminatory laws produced by the National Party since it had come to power in 1948, as well as long-standing pass laws and recent livestock limitation regulations. ANC members defied apartheid laws, mainly curfews and railway regulations, were arrested, charged in court and chose to go to gaol rather than pay a fine. Leaders were banned, arrested and charged under the Suppression of Communism Act.

Over 71 per cent of the 8,326 arrests took place in the Eastern Cape and the first acts of passive resistance took place in Port Elizabeth. That city also saw the most arrests (2,007), followed by East London (1,322).Footnote19

By the end of 1952 the campaign had ‘foundered’, as Nelson Mandela put it.Footnote20 There had been violent clashes between police and location dwellers in four cities with the last, in East London, so severe that the campaign came to an immediate halt in the Eastern Cape and fizzled out soon after elsewhere in the country. The first clash was in Port Elizabeth on 18 October. Following a dispute about a stolen can of paint, the police shot and killed seven Africans, according to the official toll, while angry mobs retaliated by killing four white men and gang-raping the wife of one of the white victims.Footnote21

On 1 November, Minister of Justice C. R. Swart issued the warning cited at the start of this article: the government, aware of the killing of whites during the Mau Mau uprising, would not allow a position in South Africa like that which had developed in Kenya. The police were mandated to act quickly and drastically.Footnote22 Two days later, the police shot and killed three Africans at Denver hostel in Johannesburg in a protest over a rent increase.Footnote23

On 7 November, after the ANC in Port Elizabeth announced plans for a strike on 10 November, Swart invoked the Riotous Assemblies Act and banned all non-religious public gatherings in Port Elizabeth, East London and King William’s Town. He also invoked the Suppression of Communism Act and banned 52 leaders from attending gatherings anywhere in the country for six months. The list included several East London ANC Youth League leaders, but they were only served their orders on the afternoon of Saturday 8 November, an important factor in the subsequent events in East London. Despite these measures there was a further clash in Kimberley that Saturday following an incident in a beer hall. In the riot that followed, police shot and killed 13 people.Footnote24

Bloody Sunday

The final outbreak began on the afternoon of Sunday 9 November 1952, on a bare patch of land called Bantu Square in the Tsolo section of the East Bank Location. By the evening the Duncan Village area was also affected.

Despite the ban on public gatherings, the leader of the ANC Youth League in East London, Alcott Gwentshe, visited the police headquarters in Fleet Street on the morning of 8 November and obtained permission for a meeting in Bantu Square on condition that it would be a prayer meeting and not a political meeting.Footnote25

Shortly afterwards, he and other ANC leaders in the city were served with banning orders which made it illegal for them to attend the meeting they had organised. To complicate matters there was a leadership dispute at the time, and that night Walter Sisulu, Secretary General of the ANC, arrived from Johannesburg to sort it out. This meeting began at 11 p.m. on the Saturday night in a hall in the location and continued on Sunday afternoon outside Duncan Village in a house in North End. So it happened that ANC and Youth League leaders were not at the fateful meeting in Bantu Square.Footnote26

Meanwhile, the police were on high alert. Reinforcements had been sent to Port Elizabeth from Cape Town and Johannesburg in preparation for the strike on 10 November, and in East London all local police were on standby for the weekend, supplemented by a force of 40 (including 30 Zulu policemen) from Durban and Captain T.L. Ley from Vereeniging.Footnote27 Troop carriers filled with policemen paraded through Duncan Village on the Saturday afternoon. Four armoured cars, equipped with Vickers machine guns and manned by Defence Force soldiers, were sent from Port Elizabeth and drove through the streets of East London. Major A.L. Prinsloo, who excused the police from the Remembrance Day service in Oxford Street on Sunday afternoon, later denied that the armoured cars were deployed in the ‘unrest’ and said they were there only for training purposes,Footnote28 but local resident Ronald Mynie told documentary filmmaker Koko Qebeyi that police gathered in Duncan Village on the Saturday ‘with the big army vehicles, trucks and all that … [and] the Saracens they had those days’.Footnote29

Police estimates of the number of people at the Bantu Square meeting on 9 November 1952 vary. Major Prinsloo told the Daily Dispatch the day after that about 1,500 attended the meeting,Footnote30 but Captain C.F. Pohl, the East London police inspector who led the police action, told the inquest four months later that there were 700 to 800 people, one-third of them women. Pohl said a total of 109 policemen, of whom ‘almost half were non-European’, went to the meeting, led by himself and Captain Ley. The black policemen were armed with batons only, but the white police also had Sten (sub-machine) guns, .303 rifles with fixed bayonets, and revolvers.Footnote31 Locals later insisted that the day would not have ended with such violence had police not been brought in from outside with such heavy armoury. ‘They were hardened soldiers who were trained to shoot to kill, not local white bullies in police jackets’, wrote Koko Qebeyi.Footnote32 Police claimed that they heard shots from the crowd, found a loaded revolver on the ground, and one policeman suffered a minor head injury from a bullet. Survivors said the crowd’s only weapons were stones.

The meeting began with a prayer, but it had barely been said when the police declared the gathering to be political, therefore illegal, and ordered the crowd to disperse. When it did not do so and people started throwing stones, the police charged with batons. When two shots rang out (according to the police version only) the order was given to fire.Footnote33 Pohl said the police action, from baton charge to final bullet, lasted about 10 minutes, with ‘about 30 shots’ fired to stop the stone throwing and disperse the meeting, and ‘some further shots’ when stone throwing resumed. Pohl said the police were back at the East Bank police station at ‘4.50 pm’.Footnote34

According to various other reports, the police shot many more rounds, some with Sten guns, and made no attempt to attend to the people they had shot before withdrawing. After the first ambulance was stoned by protesters they did not allow either ambulances or fire engines into the location. It was left to location residents to transport the dead and wounded.Footnote35

With the police withdrawal, enraged residents roamed through the location, burning and destroying symbols of white control: a teachers’ college for women, a hostel for delinquent youth, a model dairy and the Catholic mission (including the church, school, clinic and convent). The two white people who were unfortunate enough to cross their paths were killed. A group of youths beat Vorster to death with sticks and another group, ranging from a teenage girl to middle-aged men and women, attacked Sister Aidan. According to eyewitnesses, she was struck with a stick, stoned, stabbed and set alight in her car. Then her body was brutally mutilated.Footnote36

After finding the white bodies, police rampaged through the location in troop carriers, wreaking the vengeance for which the Minister of Justice had paved the way, shooting into and between the densely populated homes for many hours. This is the part of the police action that day that was covered up by the authorities and when most of the victims were killed.

Journalists reported, and East London residents later told me, they saw flames leaping into the sky and heard screams and gunfire, including the rat-tat-tat of machine guns, until late that night. Some said gunfire continued throughout the night. Members of the local Skietkommando, an informal citizen force, paraded outside Fleet Street police station and more police were brought to the city. The police cordoned off the location, allowing residents to flee but no one except police to enter. Fire engines and ambulances were also not allowed to enter.Footnote37 By morning, seven buildings had been destroyed and an untold number of people killed or wounded. Although the wood and iron Catholic and Anglican churches in West Bank were burned down on the Monday night, the police attributed this to ‘hooligans’ and assured the public that the location was now ‘under control’. By the end of the week, Duncan Village was still cordoned off, but location residents were streaming out of the city. Philip Mayer estimated that some 5,000 location residents left East London in the weeks immediately after 9 November, due to both fear of white reprisals and internal divisions in the African population.Footnote38 Meanwhile, police arrested and charged at least 137 ‘Natives’.Footnote39 Adults were sentenced to imprisonment with hard labour and youths to whippings (‘strokes with a light cane’). In 1954, four men were executed, two each for the murders of Sister Aidan and Barend Vorster.Footnote40

The Death Toll: From Eight to 214

On police instructions, the Daily Dispatch kept out of Duncan Village on 9 November, but reported the following day that that ‘two Europeans and a number of natives were killed when rioting broke out in the East Bank Location’.Footnote41 The report continued: ‘[i]t is not yet known how many natives were killed and wounded but it was understood that the number was considerable’. The Minister of Police arrived in the city that night and by the next morning (Tuesday 11 November), the Dispatch was reporting ‘official casualty figures’ provided by Major Prinsloo: ‘two European civilians and seven Natives killed, three policemen injured, and 27 Natives wounded’. This is the toll that has been repeated down the years although, in an inquest months later, an eighth person, a ‘coloured’ man called Henry Lavans, was added to the list of people shot by the police. The victims were listed then as Mvandaba Kafu (46), Samuel Fotoye (45), Richard Qubudla (46), Sidney Tiffe (25), Talbot Kwoza (45), Matthews Sidinana (46), Greyton Lylendle (22) and Henry Lavans (27). No further details were provided. A magistrate concluded that the police acted in self-defence and were not to be blamed for their deaths.Footnote42

The ANC’s first official response was a written statement attributed to Gwentshe and published by the Daily Dispatch on Tuesday 11 November. Gwentshe blamed the Minister for preventing the leaders from attending the meeting. As a result, there was ‘no one to exercise a restraining influence’. Gwentshe said it was ‘a matter of great regret that two European lives were lost in the course of the disturbances’ and he called upon ‘his people to exercise calmness and restraint even in the teeth of police provocation and indiscriminate shooting’. He made no mention of the black lives lost.Footnote43 A flyer in the name of the National Action Committee of the ANC and South African Indian Congress (SAIC) protested against the police shootings and claimed the government had created ‘race riots’ by sending out ‘agents’ to ‘provoke incidents which can be used by the police as a pretext for shooting and to incite and preach race hatred’. ‘Do not be provoked’, the flyer warned.Footnote44 Mandela later distanced the ANC from the violence entirely and said that ‘the riots had nothing whatsoever to do with the [Defiance] campaign’.Footnote45

Early Accounts of the Police Action

In 1955 the Institute of Social and Economic Research at Rhodes University began a five-year research programme, the Border Regional Survey, which included three studies of African people in and around East London in the mid to late 1950s. Two of the books produced include accounts of the riots in 1952. Neither mention the death toll. D.H. Reader wrote that the police scattered the meeting ‘by force of arms’.

The real casualties are unknown but the whole incident took place in the thick of the wood-and-iron area. Here .303 rifles may well have penetrated shacks several blocks away. There is little doubt that some innocent persons at a distance from the shooting were accidentally killed or wounded in their homes.Footnote46

Mayer said the meeting on 9 November 1952 was held in defiance of the ban on meetings: ‘[i]n breaking up the meeting police used fire-arms, and several Xhosas (numbers unknown) were accidentally killed or wounded. Now violence broke out. Gangs of youths deliberated murdered two white people’.Footnote47

When ‘gangs’ attacked the mission and other buildings ‘the authorities acted firmly, and order was restored within a few days’, Mayer said, adding that ‘most of the location was basically relieved to have been “saved” by White intervention from further violence and bloodshed’.Footnote48

Reader and Mayer do not mention their sources for their accounts of the riots but in their acknowledgements warmly thank the Bantu Commissioner and Native Affairs staff, some of whom were in place in 1952. Both accounts are unusual in that they indicate that the police shooting unfolded in two parts – before and after the white murders – which is not generally the case in subsequent academic accounts. In a video interview in 1983, anthropologist Alan MacFarlane asked Mayer whether he had ‘ever been actively under very strong political or other pressure to alter [his] findings?’ Mayer replied

It was always a battle of wits … In discussions I always took, take the line that fieldwork or anthropological work in South Africa is possible if one handles it properly … on the whole it is possible to do certain work if one does it with a certain circumspection which does not mean one has to sell one’s soul.Footnote49

Could he have been acting with such ‘circumspection’ when he skirted around the police action in his accounts of the 1952 riots?

Challenges to the Official Death Toll

The first claim of a much larger death toll came from the Eastern Province Herald on 11 November 1952. The newspaper repeated the official casualty figures, but added:

Police officers feel, however, that the rioters removed many of the dead and injured from the scene of the rioting – as happened during the New Brighton trouble on October 18. Reliable sources in close touch with the events of last night confirmed that the Native death toll could be as high as 80 killed and more than 100 injured.Footnote50

The president of the Institute of Race Relations, John David Rheinallt Jones,Footnote52 the sociologist and co-founder of the South African Liberal Party, Leo Kuper,Footnote53 and American journalist Alexander Campbell, who had worked for the Daily Dispatch before joining Time and Life and was in East London in the week after the riots, also believed that the real figures were far higher than the official figure.Footnote54

Subsequently, the most vocal allegations of a massacre have come from a former policeman, Donald Card, who was one of the main investigating officers in the Sister Aidan murder trial. In 1977, seven years after leaving the police, he told American journalist Barbara Hutmacher in a published interview that police shot and killed more than 200 people in Duncan Village on 9 November 1952.Footnote55 The claim was repeated in 1993 by Lungisile Ntsebeza (after interviewing Card for his Master’s thesis),Footnote56 in 2002 by Cornelius Thomas in newspaper articles and in 2007 in Card’s auto/biography, written by Thomas.Footnote57 In a video released in 2011, Duncan Village filmmaker Koko Qebeyi included an interview with Card in which he repeated the claim.Footnote58 It is further repeated in articles by Breier in 2015, Bank and Carton in 2016 and Bank and Qebeyi in 2017.Footnote59

In an interview with me in 2016, Card said he was not permitted, as a plain clothes detective, to go into the location the night of 9 November, but he was at the police headquarters in Fleet Street during the day and in his police accommodation nearby in the evening.Footnote60 He heard the police shooting from the time they dispersed the crowd around 4 p.m. until at least 9 p.m. that night. From his room he could see the flames and hear the shots emanating from Duncan Village.

Some people in East London said they heard shooting all night – some of them even got under their beds, they were so scared … there were gaps of about five or ten minutes, and then you’d hear ‘Whrrrrrrrr!’[referring to machine gun fire]

When the policemen came back that night, there was all that talk about shooting. There was a Rothman chap. I said, how many people did you shoot? Oh, he said, about 40. Okay, that could have just been a passing remark, there was nothing serious in that discussion. But most of them said we shot hundreds. The general message that came back [was that] there were hundreds [shot].

Card said that the official figures reflected only the dead and injured who were taken to Frere Hospital on 9 November. Families soon realised that if they went to the hospital they would themselves be arrested along with the patients. Bodies were hidden away and then buried secretly in or outside East London or in rural areas. The police investigating team were told of these deaths and burials during their investigations and started keeping a tally in a small green exercise book. The death toll recorded in that book eventually reached 214. The book would have provided crucial evidence for historians, but it ‘disappeared’, Card said.

Following the publication of Bloody Sunday, I have been asked whether Card could be regarded as a reliable witness, given his reputation as a security policeman in the 1960s. I have noted that some of these people accept his word on the ‘cannibalisation’ of Sister Aidan. Likewise, there are others who accept his word on the massacre but dispute what he and others have said about Sister Aidan.

Card, who died in 2022 at the age of 93, was the youngest (24 at the time) of the five policemen who investigated the murders of Sister Aidan and Vorster. Card stayed with the Sister Aidan case to its completion in July 1953. His isiXhosa fluency and his success in tracking down suspects and securing convictions were highly regarded in the East London white community. If they knew of his violent methods they turned a blind eye, at least at that time. In the Sister Aidan murder trial he was accused of torturing suspects in custody, in particular Mavis Mkobeni, the young woman who was charged with the nun’s murder. She gave a graphic description of the torture that eventually led to her confessing to stabbing Sister Aidan. Card denied her allegations but, in the trial, he did admit he was ‘not particularly gentle’ with suspects. The judge accepted his version and ruled her statement admissible as evidence. She was acquitted on the grounds that Sister Aidan was already dead at the time she stabbed her and there were no subsidiary charges.Footnote61 When the TRC came to the Eastern Cape in the 1990s Card was called to account for numerous allegations that he had tortured detainees in custody in the 1960s.Footnote62

Card left the police in 1970 when the editor of the Daily Dispatch, Donald Woods, offered him the position of managing director of a subsidiary company of the newspaper, the private security firm Night Hawk Patrols.Footnote63 Here Card soon had ‘a staff of 800, 750 of them black, and a kennel of Alsatian guard dogs’ and was one of the highest-paid executives in the city.Footnote64 He also became a member of the Progressive Party and was mayor for East London for three terms. Woods, who won fame as a liberal editor and supporter of Steve Biko, found Card ‘extraordinary’ and was still describing him as a family friend in a book published in 2000.Footnote65

It was in the 1970s that Card came out with the claim that more than 200 people died. It is difficult to be certain of Card’s truthfulness or his motives. Card was certainly a confident self-publicist who fought back with his own narratives when criticised – to the point of insisting on a right to respond to an article by Leslie Bank and Andrew Bank in this journal which detailed his violence.Footnote66 However, there would have been no advantage for him in the 1970s to speak about the massacre, as there might have been after the 1990s. It was hazardous to speak out against the police during apartheid and anyone in the security industry, as he was, needed to maintain a good relationship with the police. Given the timing of his first public statement about the number of deaths, and other evidence which I will discuss below, I am inclined to think that it has validity.

Elderly Residents Remember

Elderly people from Duncan Village whom I interviewed were unable to provide figures but insisted that the death toll was far higher than that quoted officially. Mxolisi Mhlekiswa was 15 years old at the time and at the beach when he saw people with bundles on their heads, fleeing from the police. On his way home to Duncan Village ‘there were soldiers and police everywhere and they were shooting all over’. He also witnessed the mutilation of Sister Aidan’s body and said he was so traumatised by this that he did not find out how many black people had been killed. He had been a pupil at the Catholic mission school and a patient of Sister Aidan’s.Footnote67 Mavis Mkobeni, who was acquitted of Sister Aidan’s murder, told me in 2017 that ‘hundreds’ were killed. She was shot in the leg and saw dead and wounded people, including many women, lying on the ground before she was bundled into a police van and taken to gaol.Footnote68 There are no female names in the official death toll, yet according to police figures at least one-third of those who attended were women.Footnote69 They included members of manyano women’s groups. In the oral history of manyano women, ‘hundreds’ of women died at Bantu Square.Footnote70

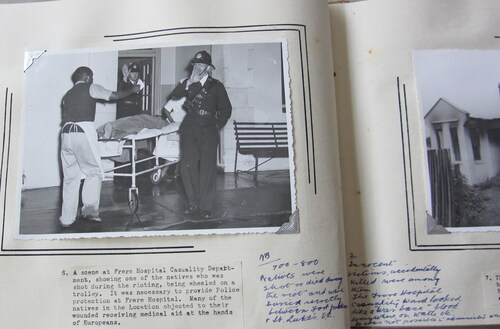

Sister Ann Wigley, head of the Dominican congregation of nuns to whom Sister Aidan belonged (the ‘King Dominicans’Footnote71), was at boarding school in King William’s Town at the time. Her father, a lawyer in Willowvale in the then Transkei, told her that 150 people had been killed.Footnote72 In the Dominican archives in Johannesburg an anonymous handwritten note in a photo album records that ‘700 to 800 Natives were shot or died during the riot’ (this figure probably draws from Captain Pohl’s crowd estimate) and that ‘the Frere hospital casualty ward looked like a “war base” – blood everywhere on walls etc. It was not possible to administer anaesthetics. The rush and crowd was [sic] too great’.Footnote73

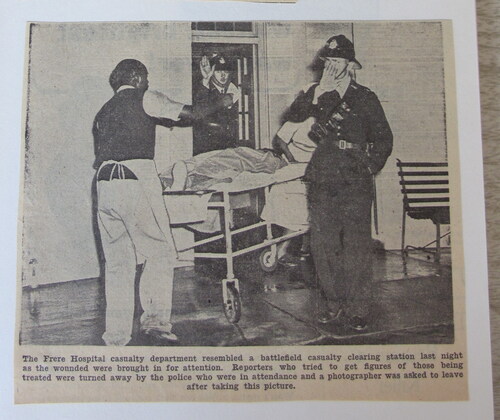

While police prevented journalists from entering Frere Hospital on the night of 9 November (see ) and hospital authorities refused to divulge figures, the Daily Dispatch did report that five operating theatres were in use that night and several nurses described the chaos.Footnote74

Figure 2. Police preventing journalists from entering Frere Hospital. (Source: Daily Dispatch, 10 November 1952. Cutting from King Dominican Archives, Johannesburg.)

Connie Manse Ngcaba, a Frere Hospital nurse at the time, wrote in her memoir of injured people in the emergency unit ‘groaning and pleading for help’, some shot in the head and back so that if they survived they would be ‘permanently crippled or paralysed’, bodies waiting to be certified by a doctor before they could be removed, and the faces of white doctors and nurses ‘as they manhandled the injured as if they were rags’.Footnote75

Asymmetries of Power

Massacres, by definition, involve an imbalance of power that enables the perpetrators to overwhelm their victims and emerge unharmed themselves. compares the size and armoury of the police force at Bloody Sunday with that at Sharpeville.

Available figures, set out in , indicate that the proportion of policemen to crowd members was at least as high as, if not higher than, the proportion at Sharpeville. They were probably as heavily armed and, if one takes account of the second round of shootings, the East London massacre took place over a far longer time – hours compared with seconds.

Table 1. A comparison between the size and armoury of police and crowd at Duncan Village, 1952, and Sharpeville, 1960

Semelin invites one to distinguish between those who organise a massacre from afar and the ‘executioners’ who carry it out.Footnote76 There was certainly considerable planning ahead of the events – from the Minister’s warnings to the additional police and armoured vehicles – making the government complicit in the events that followed. The first shooting followed the orders of Pohl and Ley. Whether the men in troop carriers in the second round of shooting were acting according to plan or not is a moot point.

Campbell wrote about young white policemen at the funeral of one of the victims. He said they arrived at the gravesite in a troop carrier, armed with rifles and in one case a Sten gun, ‘came out of the troop carrier with a great clatter of boots and rifles and squatted on the grass a few yards from the Africans’.Footnote77

They talked in loud, rough voices and watched the Africans irritably. The funeral service started, and the women began singing hymns. Some of them wept. In elaborate pantomime one of the young policemen mockingly wailed his grief. His companions roared with laughter.

When the service was over … a slim, well-dressed African walked slowly away towards his automobile. He was Dr Robert Ross Mahlangane [Mahlangeni], one of the local leaders of the ANC and like many of them a medical man. ‘Black pig!’ grunted one of the policemen as he passed.Footnote78

Although these policemen might have been particularly boorish, their attitude was an extension of the view commonly held by whites at the time that black people were at a different stage of civilisation to whites. It was not only the view of the National Party, it was also the view of the Catholic church at the time, although the church did espouse an evolution towards fuller participation which the Nationalists did not.Footnote79

Conditions for Secrecy

Massacres, as Semelin has noted, tend to involve events ‘in camera’, in places that have been sealed off, and where ‘violence may surpass all limits’.Footnote80 Bloody Sunday was no exception. Those who seek evidence of the scale of the police violence in the form of written statements, death registers or marked grave sites are disappointed. Some questions will never be conclusively answered because of the secrecy involved.

Police created the conditions for secrecy by keeping the press out of Duncan Village that Sunday, by warning whites who might have gone into the area that they should not go there on the Monday (including a teacher and a pharmacist that I know of),Footnote81 and by maintaining a cordon around the location for at least a week afterwards. The city council perpetuated the secrecy in its meetings and records, the government issued official, sanitised reports, and among the residents of East London, white and black, a culture of silence set in.

The Press

East London had one major newspaper, the Daily Dispatch, which at that stage focused on white readers and seldom reported location news.Footnote82 The newspaper ‘played down’ the Defiance Campaign ‘so as not to give undue encouragement to the resisters’, journalist J.L. McFall later admitted.Footnote83 At the police request, the Daily Dispatch did not send reporters to Duncan Village on 9 November and relied on police statements.Footnote84 The one journalist who could have given an eye witness account because he lived in Duncan Village was J.J. Matoti, who wrote for Imvo Zabantsundu, but he was also a Youth League leader and could not attend the meeting due to the banning order which he was served the day before and in any case was part of the ANC leadership meeting that afternoon. If he asked no questions afterwards, it is almost certainly because he feared he might be arrested. The Imvo reports on the day do not have bylines, carry no eyewitness accounts and contain no more information about the police killings than the white newspapers. At Sharpeville, in contrast, photographer Ian Berry and journalist Humphrey Tyler from Drum witnessed the massacre and produced vivid photographs and graphic accounts.Footnote85 In addition to Drum, several newspapers and magazines employed black journalists, and white journalists regularly covered news about black politics in Johannesburg.

The City Council

The East London City Council held its discussions of the riots in camera or made the minutes confidential.Footnote86 Councillors voted against a proposal that it institute a commission to investigate the cause of the riots. Arguing against the motion, Mayor F.T. Fox said that in the interests of keeping the peace in East London, he had kept certain details secret.

It was purely an anti-white demonstration, attended by brutal savagery and even cannibalism, and was but an indication of the underground work that has been going on for a long time by subversive elements amongst people who in many cases are uneducated, and whose civilisation is but a veneer laid over a solid background of barbarism.Footnote87

The mayor concluded he could not see any purpose in agreeing to the motion, ‘for apart from anything else, we immediately indicate to the native that maybe we are at fault and to blame’.Footnote88 His words held sway and the motion was not accepted. The council did not investigate the riots.

Registration of Deaths and Burials

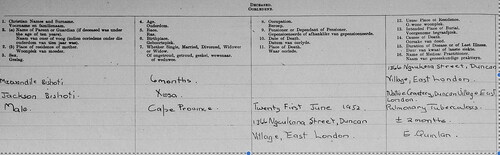

Registration of deaths and burials seemed to be a promising route of enquiry into the scale of killing but this too has proved elusive. Until late June 1952, East London’s Home Affairs (interior) Department reported every death that was brought to the attention of the formal system, whether through private doctors, clinics or Frere Hospital, regardless of race. records the death of a six-month old Xhosa baby, who was declared dead at his home in Duncan Village by Dr Elsie Quinlan (Sister Aidan) on 21 June 1952.Footnote89

Figure 3. Record of the deaths of two infant patients of Dr Elsie Quinlan’s in the East London death register, 1952. (Source: Western Cape Archives, East London Register of Deaths, KAB, 3/ELN, HAEC, 1/2/6/6/18.)

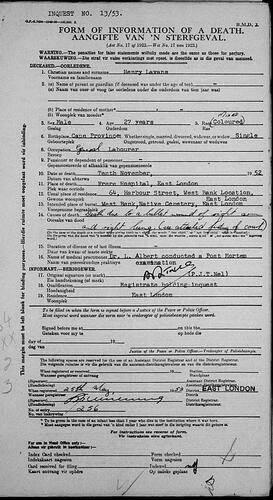

In a later register I found the deaths of Sister Aidan and Barend Vorster faithfully recorded, as well as that of Henry Lavans (the ‘coloured’ man who was killed by police), but not those of the African people killed, not even the seven who were ‘officially’ declared dead on 9 November 1952.Footnote90 I was also able to obtain death certificates for Quinlan, Vorster and Lavans online, through FamilySearch. is a copy of Lavans’ certificate.

Figure 4. The death certificate for Henry Lavans. (Source: ‘South Africa, Cape Province, Civil Records, 1840–1972’, database with images, FamilySearch, accessed at https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:Q2QM-8J68, retrieved 10 March 2021. Henry Lavans, 10 November 1952, East London, Cape Province, South Africa; citing National Archives, Pretoria; FHL microfilm 1,796,207.)

On 1 July 1952, the government changed the rules for the registration of ‘native’ births and deaths. Previously registration was compulsory in urban areas only and haphazardly applied by the Department of the Interior. East London’s efficiency was an exception. From 1 July 1952 registration of ‘native’ births and deaths was compulsory throughout the country and officials of the Department of Native Affairs were tasked with the duties of registration.Footnote91 This change contributed to the centralisation of the administration of African people in the Department of Bantu Affairs, which was fast becoming a ‘state within a state’.Footnote92 At the same time, it created extra work for Native Affairs officials who were already struggling to cope with the bureaucratic burden of the new system of labour bureaus. The Secretary for Native Affairs complained that the extension of its activities and many resignations had led to a serious shortage of staff.Footnote93 It is possible that there was a hiatus in the registration of deaths at this time.

I have not found anyone, either researcher or archivist, who has been able to advise where the deaths of African people in East London were recorded after 27 June 1952. The correspondence files of the Bantu Commissioner for East London for 1937 to 1957 might have provided some answers but they have disappeared from the Western Cape Archives.Footnote94

Missing Court Records

In the days following the riots, the ANC, the South African Indian Congress, the seven parliamentary Native Representatives and the Institute of Race Relations all called for an inquiry. To each of these appeals, the Minister had the same response: ‘prosecutions connected with the riots were being carried out in the Law Courts and it would be preferable to await the outcome’.Footnote95

In considering whether the courts paid any attention to the Minister’s promises and the police actions on Bloody Sunday, one needs to take account of the number of relevant court records that are missing. In the Western Cape Archives, the folders for the records of the murder trials are virtually empty. There are only shorthand notes in the folder on Sister Aidan’s murder and a map and a couple of statements in the folders on Barend Vorster’s murder.

Folders with the proceedings of 63 cases heard by judges of the Grahamstown Supreme Court (GSC), in Port Elizabeth, East London and King William’s Town in 1953 (the year when the Bloody Sunday trials took place) are entirely missing. Among these were all the public violence cases arising from the events of 9 November. The files were already missing in 1983 when archivist Clive Kirkwood assembled an inventory of GSC cases from 1942 to 1954.Footnote96 Anne Mager and Gary Minkley also noted their absence.Footnote97

In the National Archives in Pretoria there is a collection of police folders on ‘native unrest’ in the Eastern Cape in 1952. Inside, there are no folders for East London and New Brighton (Port Elizabeth), although they are listed.Footnote98

I was fortunate to find a copy of the full court record in the Sister Aidan murder case in the King Dominican archives in Johannesburg. I found details about the trials for the murder of Barend Vorster and the four white people killed in Port Elizabeth in the Governor-General executive files in the National Archives (the Governor-General had to sign off the executions.) I relied on newspapers in the South African Library in Cape Town for reports on the public violence, housebreaking and arson trials.

I found no references to the casualties inflicted by the police in any of these sources, beyond the newspaper reports on the inquest into the deaths of the ‘official’ eight, in which the police were found to have acted in self-defence and not to be blamed for the deaths.Footnote99

Collective Silence

Semelin speaks of a wider community that provides tacit consent for a massacre.Footnote100 It was such a community that wrote letters to the Daily Dispatch after the events, congratulating the police and calling on whites to stand together to face the threat of black people ‘rising against the whites in Africa’.Footnote101 Others closed their eyes and mouths in the ‘deathly hush’ which Campbell described. He said city councillors told him they were sworn to secrecy, the police were obviously under strict instructions to say nothing, the hospital superintendent refused to produce his case records and even reporters on the Daily Dispatch, his old paper, were not talking. Only ‘after much hard digging, involving furtive interviews with Red Cross officials, less inhibited doctors and the undertakers who carried out African burials’, was he able to ‘piece bits of the story together’.Footnote102

Although there were some revealing comments about the events in Duncan Village during the 1950s, and Card’s challenging public statements from the 1970s, these were not widely discussed or recalled in public by those associated with the victims: the church, Duncan Village residents and the ANC. Reluctance to speak about a massacre for decades afterwards is not uncommon. In Tulsa, there was a ‘culture of silence’ for many years.Footnote103 Victims’ families bury their memories in silence as a strategy to survive in the same cities as their oppressors. Tom Lodge found that when Sharpeville survivors started telling their stories to the TRC in the 1990s, their recollections were ‘fresh and vivid’ and their narratives were ‘shaped by emotions and feelings that for thirty years needed to be contained and curtailed’.Footnote104 Unfortunately the TRC did not provide a similar platform for the survivors of Bloody Sunday.

Memorialisation of the events on Bloody Sunday is particularly complex because violence and victims on both sides need to be acknowledged and, as Njabulo Ndebele said in his speech at the sixtieth anniversary of Sister Aidan’s death, ‘it has become a matter of habit for us to keep telling the stories of what was done to us. We do not tell as much the stories of what we did’.Footnote105

One also needs to take account of the extent of the mutilation of Sister Aidan’s body. Although the ANC blamed the police for triggering the violence, the fact that her body was dismembered and ‘cannibalised’, as the Daily Dispatch and other media put it, rendered the topic unspeakable – publicly at least.Footnote106 Dr James Njongwe, acting Cape leader of the ANC at the time, was ‘horrified at the savagery displayed by his own people’.Footnote107 At a local level, the ANC has braved the topic in recent years. The local ANC was extensively involved in the fiftieth anniversary events in 2002 and to a lesser extent in the events of 2012, which were steered by the Catholic church.Footnote108 In 2022, the Eastern Cape Legislature named a boardroom after Sister Aidan in a ceremony to honour human rights activists. A memorial to Sister Aidan was erected on the mission property in 2002, but there is no memorial to those whom the police killed, not even the eight in the official death toll, nor, to my knowledge, any steps to include the events of Bloody Sunday within the national liberation narrative.

Secret Burials

Frere Hospital might have been very busy on the night of 9 November but there were many people who did not seek help at the hospital or take their dead to the mortuary lest they be arrested. Families attended to the wounded themselves and buried their dead in secret. Mxolisi Mhlekiswa said that ‘[t]here was no chance for anyone to take their dead to the mortuary. If you even went close to the mortuary, if you revealed that you knew a person that was shot, you were also guilty. So people didn’t go to the mortuary’.Footnote109

According to various sources, including Donald Card, bodies were buried informally, mainly in nearby rural areas. A ferry owner told him that he took eight bodies across the Kei River and a truck owner said he took 22 bodies to be buried near Dongwe Location, outside Berlin. The anonymous scribe in the Dominican photo album wrote that the people who were killed ‘were buried secretly between Fort Jackson and St Luke’s [an Anglican mission]’ (see ). These sites are not far from Dongwe Location.

Figure 5. The Dominican photo album with the Daily Dispatch photograph of police preventing entry to Frere Hospital, their own caption and anonymous notes on the massacre. (Source: King Dominican Archives, Johannesburg.)

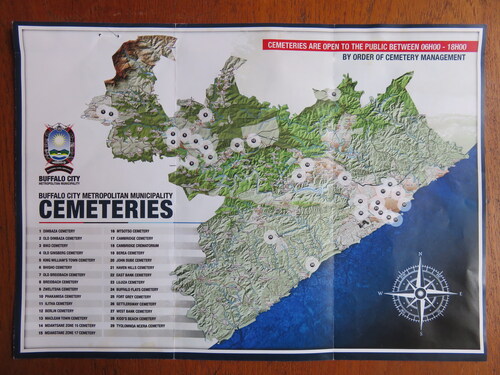

Cemetery authorities in East London confirmed that it was common at the time for black people in the locations around East London to bury their dead informally in unofficial burial grounds, around the city or in rural areas, without reporting their deaths. The manager’s office of the Cambridge cemetery in East London has a large map on the wall showing 29 official cemeteries in the Buffalo City Municipality and over two hundred informal burial grounds ().Footnote110 St Luke’s, Fort Jackson and Dongwe are all labelled as informal burial sites.

Figure 6. Map of cemeteries in Buffalo City Municipality. (Source: M. Breier, private collection.) Note: The more than 200 informal burial grounds are marked on this map but not visible in this figure. The circles indicate the official cemeteries.

Meanwhile, there was controversy in the city council as to where the dead who had ended up in the state mortuary should be buried. Dr Robert Mahlangeni applied for permission for the ANC to bury bodies that had not been claimed by their families. The mayor refused and instructed that these bodies be buried anonymously as paupers.Footnote111

Mhlekiswa and another elderly resident, Mrs N., told me that bodies were buried in the cemetery alongside the Mzonyana river, now overgrown and abandoned, next to Douglas Smit Highway. The only marked grave today is that of Alcott Gwentshe (). Mrs N. said nurses from Frere Hospital told her that ‘there were a lot of bodies, it was very sad, they were covered with white linen [and] stacked on top of each other and buried in the place where Gwentshe’s grave is’.Footnote112

Figure 7. The grave of Alcott Gwentshe in the otherwise abandoned Mzonyana cemetery. (Source: M. Breier, private collection.)

Mhlekiswa said some bodies were buried on land in Duncan Village which is now occupied by houses and a hostel. In 1958, while the hostel was being built, children discovered piles of human bones packed next to the construction site, he said. ‘The whole township came and they were saying these were their relatives. They were told that the land was needed and the bones would be buried somewhere else, but no one knows where the bones got buried’.Footnote113

Residents also talk of deaths and burials in Fort Glamorgan prison. Mrs N’s brother was gaoled for six months for breaking a curfew during the Defiance Campaign. He told his sister that ‘[t]he prisoners were beaten and made to carry stones. They were bruised and died there. They were stacked on top of each other and buried in that [Fort Glamorgan] graveyard’.Footnote114

Searching for cemetery records proved fruitless. The Cambridge cemetery has detailed records on site of the (mainly white) burials dating back to the early 1900s, but the records of ‘native cemeteries’ were destroyed, I was told, when an administration building in Mdantsane was burned down in civil unrest in the 1980s. There should have been some references to the eight ‘official’ burials in the town clerk’s records in the Western Cape Archives, but the East London ‘Native Cemeteries’ folder contains no records at all for the period between 4 November 1952 and 2 December 1952, the month in which any burials would surely have taken place.Footnote115

The lack of any obvious graves after a massacre is not unusual. There were very few marked graves after the Tulsa massacre and it took nearly a century for authorities to start excavating Oaklawn Cemetery, which is believed to have been the main burial site. Three years later the mayor of Tulsa reported that 22 sets of remains had been excavated but it was not yet established that they were victims. Further research involved seeking to match the DNA of the remains with that of surviving relatives.Footnote116

The question arises: could there be an investigation into the burial sites in East London now, more than seven decades later? In 2005, a Missing Persons Task Team was established following a TRC recommendation. Located within the National Prosecuting Authority, the team’s mandate was to locate the graves of people who went missing between 1 March 1960 and 10 May 1994. By 20 April 2018 they had uncovered the remains of 138 missing persons out of an estimated 477 identified in the TRC. Unfortunately, burials in 1952 are not within the mandate period and therefore there would be no funds to investigate them.

Conclusion

In this paper I have revisited the events of 9 November 1952 with a focus on the police violence and the black deaths. I have drawn on international literature on massacres to provide a wider perspective on questions that cannot be answered conclusively, such as the exact numbers killed and the locations of victims’ graves.

From the international literature it is clear that the events of Bloody Sunday bear all the hallmarks of a massacre. While the exact death toll cannot be determined, it was certainly more than the official death toll and over 200 is possible. The state’s inability to contain the Defiance Campaign through the courts, the ongoing complaints of whites fearful of a Mau Mau-type rebellion in this country, and the killing of four white civilians in Port Elizabeth primed the state and police for the kind of violence that manifested on Bloody Sunday. While the police granted permission for the Sunday afternoon meeting to go ahead, they simultaneously mobilised extraordinary resources, from Natal and the Transvaal as well as the Eastern Cape, and excused themselves from the Remembrance Day ceremony to be held at the same time. In Duncan Village, the conditions were ripe for the police to execute the Minister’s threats with impunity. The location was cut off from the rest of the town and the press were not permitted to enter. Whites who might have come to the location on the Monday were warned in advance not to do so.

Records of different kinds are scant or unavailable. The long-standing practice of informal burials prepared the way for secret, unofficial burials but makes it difficult for later generations to find the graves. The city council would have had an obligation, at least, to record the black deaths. However, there had been changes in the rules for the registration of African deaths just four months before and this transferred responsibility from the council to the Department of Native (Bantu) Affairs, making it possible for the deaths to go unrecorded. Calls by the ANC, city councillors and liberal whites for investigations were rejected.

Analysis of the manpower and firepower indicates that the police were more heavily armed than those at Sharpeville and less outnumbered. In the second round of shooting, people were more thinly spread as they darted in and out of houses, but the police shot for hours, using Sten guns as well as rifles and revolvers, compared with less than a minute of shooting at Sharpeville. Claims that the police killed more people than at Sharpeville are plausible. Whether they entered the location that day intending to do so is uncertain. The fact that they withdrew to the police station after the first round of killings is an indication that the slaughter might have ended there had circumstances not changed. The people of Duncan Village retaliated with fire and violence of their own. After discovering the white bodies the police, who were mostly strangers to the area, took revenge.

New research, published just as this article went to press, raises the Sharpeville death toll from 69 to 91. The Bloody Sunday massacre of 1952 is not addressed.Footnote117 Guy Lamb has considered the effect of police massacres on police reform and noted that when the protesting group did not pose a serious threat to the police no notable police reforms were introduced afterwards.Footnote118 This was the case after the Bulhoek massacre in 1921, in which 800 police mowed down 500 protesters using military-style tactics. The police action was widely condemned but the police apparently learned little from the slaughter. Thirty years later, in East London, they went to a meeting of unarmed protesters with rifles, revolvers and Sten guns and shot for hours. Again, the people were no match for their firepower and little was learned. Eight years on, when an unarmed crowd assembled outside the police station at Sharpeville on 21 March 1960, the police were similarly armed.

Georges Santayana has said that ‘those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it’.Footnote119 For this reason alone, the tragic killings of Bloody Sunday, on both sides of the political divide, deserve to be remembered.

Honorary Research Associate, School of Education, University of Cape Town, Private Bag X3, Rondebosch 7701, Cape Town, South Africa. Email: [email protected]

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9397-2436

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Zuko Blauw of the East London Museum and chairman of the Sister Aidan Quinlan Community Trust for his assistance with the isiXhosa interviews cited in this paper, and for accompanying me on many of my visits to Duncan Village. I also thank Mary-Anne Makgoka for the translations and transcriptions of the isiXhosa interviews. Research grants from the Henry Nxumalo Fund for Investigative Journalism, the Association of Non-Fiction Authors of South Africa (ANFASA) and the National Research Foundation (NRF Incentive Funding for Rated Researchers) are gratefully acknowledged.

Notes

1 ‘Polisie sal vining en sterk optree’, Die Burger, Cape Town, 3 November 1952, p. 1. Translation by author.

2 M. Breier, ‘The Death that Dare(d) Not Speak its Name: The Killing of Sister Aidan Quinlan in the East London Riots of 1952’, Journal of Southern African Studies, 41, 6 (2015), pp. 1151–65.

3 M. Breier, Bloody Sunday: The Nun, the Defiance Campaign and South Africa’s Secret Massacre (Cape Town, Tafelberg, 2021).

4 This possibility was raised by Leslie Bank and Benedict Carton in ‘Forgetting Apartheid: History, Culture and the Body of a Nun’, Africa, 86, 3 (2016), pp. 472–503. The seminal article on the riots by Anne Mager and Gary Minkley mentions only the official death toll. See A. Mager. and G. Minkley, ‘Reaping the Whirlwind: The East London Riots of 1952’, in P. Bonner, P. Delius and D. Posel (eds), Apartheid’s Genesis: 1935–1962 (Braamfontein, Ravan Press, 1993), pp. 229–51.

5 H. Ndlovu, ‘Forgotten Bodies or Silenced Voices? Recasting Women’s Voices at the Bantu Square Massacre of East London, 1952’, in this Part-Special Issue.

6 J.L. McFall, Trust Betrayed: The Murder of Sister Mary Aidan (Cape Town, Nasionale Boekhandel, 1963); Bank and Carton, ‘Forgetting Apartheid’.

7 The initial death toll, accepted by the TRC, was 23, but by the time Mbeki unveiled the memorial in 2008 this had risen to 32. See South African Press Association, ‘Truth Commission to Probe Duncan Village Massacre’, 22 September 1996, available at https://www.justice.gov.za/trc/media/1996/9609/s960922a.htm, retrieved 18 October 2022.

8 J. Semelin, ‘In Consideration of Massacres’, Journal of Genocide Research, 3, 3 (2001) p. 384.

9 A. Anisin, ‘Comparing Protest Massacres’, Journal of Historical Sociology, 32, 2 (2019), p. 258; Semelin, ‘In Consideration of Massacres’.

10 Ibid., pp. 379, 385.

11 Ibid., p. 379.

12 Anisin, ‘Comparing Protest Massacres’, p. 269.

13 L. Ryan, ‘Settler Massacres on the Australian Colonial Frontier, 1836–1851’, in P.G. Dwyer and L. Ryan (eds), Theatres of Violence: Massacre, Mass Killing and Atrocity Throughout History (New York, Berghahn Books, 2012), pp. 94–109.

14 D.H. Makobe, ‘The Price of Fanaticism: The Casualties of the Bulhoek Massacre’, Scientia Militaria: South African Journal of Military Studies, 26, 1 (1996), pp. 38–41. To complicate the issue further, the memorial at Bulhoek lists only 213 names.

15 Oklahoma Commission to Study the Race Riot of Tulsa 1921, ‘Tulsa Race Riot’, 28 February 2001, p. 23, available at https://www.okhistory.org/research/forms/freport.pdf, retrieved 9 December 2022.

16 K.A. Wagner, ‘“Calculated to Strike Terror”: The Amritsar Massacre and the Spectacle of Colonial Violence’, Past & Present, 233, 1 (2016), p. 186.

17 Y. Rana, ‘101 Years On, No One Knows How Many Died at Jallian Bagh’, Times of India, Mumbai, 20 January 2021, available at https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/amritsar/101-years-on-no-one-knows-how-many-died-in-jallianwala-bagh/articleshow/80357711.cms, retrieved 16 January 2023.

18 P. Frankel, An Ordinary Atrocity: Sharpeville and its Massacre (Johannesburg, Witwatersrand University Press, 2001).

19 T. Lodge, Black Politics in South Africa Since 1945 (Johannesburg, Ravan Press, 1983).

20 N. Mandela, Long Walk to Freedom (London, Little, Brown, 2010 [1995]), p. 130.

21 Union of South Africa, Annual Report of the Commissioner of Police for the Year 1952 (Pretoria, Government Printer, 1953).

22 ‘Polisie sal vining en sterk optree’, Die Burger, p. 1.

23 Union of South Africa, Annual Report of the Commissioner of Police.

24 Ibid.

25 ‘Sequel to E.L. Riots’, Daily Dispatch, East London, 16 March 1953, p. 5.

26 Western Cape Archives (hereafter WCA), Regina vs Alcott S. Gwentshe, KAB, GSC, 1//2/1/644, 388/53.

27 ‘Move to End Tension at E. London’, Cape Times, Cape Town, 11 November 1952, p. 1.

28 Ibid.

29 M.K. Qebeyi, Dark Cloud (East London, M.K. Productions, 2011).

30 ‘Riot Casualties 9 Dead, 30 Wounded’, Cape Times, 11 November 1952, p. 7. In the body of the article the number of wounded given was 27, and this is the figure that the police later repeated.

31 WCA, Pohl, Statement dated 22 January 1953, Regina vs Douglas Lumkwana & Welle Maduze, KAB, GSC 1/2/1/661, 585/53; ‘“Crowd Became Aggressive When We Arrived”’, Daily Dispatch, 13 April 1953.

32 M.K. Qebeyi, ‘The 1952 Defiance Campaign in East London’ (unpublished paper, 2012).

33 WCA, Pohl, Statement dated 22 January 1953.

34 Ibid.

35 ‘Many Die in East London Riot’, Daily Dispatch, 10 November 1952, p. 7; McFall, Trust Betrayed, p. 142.

36 Breier, Bloody Sunday, pp. 176–91.

37 ‘Many Die’, Daily Dispatch, p. 7; personal correspondence following publication of Bloody Sunday, 2021–23.

38 P. Mayer and I. Mayer, Townsmen or Tribesmen: Conservatism and the Process of Urbanization in a South African City, 2nd edition (Cape Town, Oxford University Press, 1971), p. 83.

39 Union of South Africa, Annual Report of the Commissioner of Police, p. 6.

40 See Breier, Bloody Sunday, for a detailed account of the trials.

41 M. Breier interview with Donald Card, East London, 16 November 2018.

42 ‘Police Not Responsible for Eight Deaths’, Daily Dispatch, 25 May 1953, p. 3.

43 ‘Permission Was Given for Prayer Meeting’, Daily Dispatch, 11 November 1952, p. 7.

44 ‘A.N.C. Call for Restraint’, Cape Times, 11 November 1952, p. 4.

45 Mandela, Long Walk, p. 127.

46 D.H. Reader, The Black Man’s Portion: History, Demography and Living Conditions in Native Locations of East London, Cape Province (Cape Town, Oxford University Press, 1961), p. 26.

47 Mayer and Mayer, Townsmen or Tribesmen, p. 82.

48 Ibid., pp. 82, 88.

49 P. Mayer, interviewed by A. MacFarlane, 13 July 1983, available at https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/619, retrieved 27 March 2023.

50 ‘Trouble Flares Up in E.L. Again’, Eastern Province Herald, Port Elizabeth, 11 November 1952, p. 1.

51 ‘Eye Witness Accounts of East London Shooting’, Advance, 27 November 1952, p. 6.

52 ‘Native Riots Attributed to Criminal Elements’, Daily Dispatch, 12 December 1952.

53 L. Kuper, Passive Resistance in South Africa (London, Jonathan Cape, 1956), p. 138.

54 A. Campbell, The Heart of Africa (London, Longmans, Green and Co., 1954).

55 B. Hutmacher, In Black and White: Voices of Apartheid (London, Junction Books, 1980).

56 L. Ntsebeza, ‘Youth in Urban African Townships, 1945–1992: A Case Study of the East London Townships’ (MA thesis, University of Natal, 1993).

57 C. Thomas, Tangling the Lion’s Tale: Donald Card, from Apartheid Era Cop to Crusader for Justice (East London, Donald Card, 2007).

58 Qebeyi, Dark Cloud.

59 Breier, ‘The Death that Dare(d) Not Speak its Name’; Bank and Carton, ‘Forgetting Apartheid’; Qebeyi, Dark Cloud.

60 M. Breier interview with Donald Card, East London, 7 November 2016.

61 WCA, Regina vs Albert Mgxwiti & seven others, KAB GSC, 1/2/1/660, 584/53.

62 See L. Bank and A. Bank, ‘Untangling the Lion’s Tale: Violent Masculinity and the Ethics of Biography in the “Curious” Case of the Apartheid-Era Policeman Donald Card’, Journal of Southern African Studies, 39, 1 (2013), pp. 7–30; D. Card, ‘Reply to the Article by Leslie Bank and Andrew Bank’, Journal of Southern African Studies, 39, 1 (2013), pp. 31–43.

63 D. Woods, Asking for Trouble: Autobiography of a Banned Journalist (London, Penguin, 1987), p. 180.

64 Hutmacher, In Black and White.

65 D. Woods, Rainbow Nation Revisited: South Africa’s Decade of Democracy (London, Andre Deutsch, 2000), p. 42.

66 Bank and Bank, ‘Untangling the Lion’s Tale’.

67 Interview with M. Breier, assisted by Z. Blauw, East London, 5 June 2017.

68 Interview with M. Breier, assisted by Z. Blauw, Mdantsane, 6 June 2017. Also interviewed by M.K. Qebeyi in Dark Cloud, 2011.

69 WCA, Pohl, Statement dated 22 January 1953.

70 See Ndlovu, ‘Forgotten Bodies’ and Carline, ‘Sewing the Revival Tents: Black Women’s Christian Organisations and the Public Duties of Home-Making in Early Apartheid East London, 1950–1963’, both in this Part-Special Issue.

71 The Dominican Sisters of the Congregation of St Catherine of Siena of King William’s Town, now based in Melrose, Johannesburg.

72 Interview with M. Breier, Johannesburg, 5 September 2019.

73 King Dominican Archives, ‘In memory of Sr. M. Aidan. O.P.’. Album of photographs compiled by Sister Damian Skinner (1953).

74 ‘Many Die’, Daily Dispatch, p. 7.

75 C.M. Ngcaba, May I Have This Dance: The Story of My Life (Cape Town, Cover2Cover Books, 2014). Quoted at greater length in Ndlovu, ‘Forgotten Bodies’.

76 J. Semelin, ‘Toward a Vocabulary of Massacre and Genocide’, Journal of Genocide Research, 5, 2 (2003), p. 203.

77 Campbell, The Heart of Africa, pp. 45–6.

78 Ibid.

79 Southern African Catholic Bishops’ Conference (SACBC), ‘Statement on Race Relations’, June 1952.

80 Semelin, ‘In Consideration of Massacres’, p. 385.

81 Personal communication in 2023 with an East London resident, whose mother was a teacher in Duncan Village; King Dominican Archives, Statement by Sister Ursula Kieslich, March 1953.

82 See D.G. Bettison, ‘A Socio-Economic Study of East London, Cape Province, with Special Reference to the Non-European Peoples’ (MA thesis, University of South Africa [Rhodes University], 1950); also the statement by Sam Kahn, reported in ‘E.L. Locations are Bad, Says Kahn’, Daily Dispatch, 24 July 1952, p. 7.

83 McFall, Trust Betrayed, p. 117; M. Breier interview with Donald Card, 17 November 2016.

84 M. Breier interview with Card, 2016.

85 See T. Lodge, Sharpeville: An Apartheid Massacre and its Consequences (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2011), p. 105.

86 WCA, East London Town Clerk’s Office, Municipal Folder, Native Riots in East Bank Location, 3/ELN, 50/665/3/1, 1343 (hereafter WCA ELN TCO Native Riots).

87 F.T. Fox, ‘Inquiry into Location Riots’, WCA ELN TCO Native Riots, p. 1.

88 Ibid., p. 4.

89 This was the last death certificate signed by Sister Aidan.

90 East London Register of Deaths, KAB, HAEC 12, 1/2//6/5/1/24 & 42. The deaths of Sister Aidan and Vorster were registered on 25 February 1953, and Lavans on 25 May 1953.

91 National Archives, Pretoria, Registration of Births and Deaths (Natives) in the Union 1947–1952, SAB NTS_9360_2/382.

92 I. Evans, Bureaucracy and Race (Berkeley, University of California Press, 1997), p. 2.

93 Report of the Department of Native Affairs for the Year 1952–53, U.G. 48/1955, p. 5.

94 WCA, KAB, 2/ELN, 3/1.

95 M. Horrell, A Survey of Race Relations in South Africa, 1952–1953 (Johannesburg, South African Institute of Race Relations, 1953), p. 33.

96 WCA, C. Kirkwood, Inventory of the Archives of the Registrar of the Eastern Cape Division of the Supreme Court of South Africa, 1865–1966, December 1983.

97 Mager and Minkley, ‘Reaping the Whirlwind’, p. 246.

98 National Archives, Pretoria, Native Unrest: Cape Eastern Division, SAB SAP, 497, 15/34/52.

99 ‘Police Not Responsible’, Daily Dispatch, p. 3.

100 Semelin, ‘In Consideration of Massacres’.

101 ‘Comments on the Riots’, Daily Dispatch, 17 November 1952, p. 3.

102 Campbell, The Heart of Africa, pp. 42–4.

103 Oklahoma Commission, ‘Tulsa Race Riot’, p. 31.

104 Lodge, Sharpeville, p. 1.

105 N. Ndebele, ‘Love and Politics: Sister Quinlan and the Future We Have Desired’, Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, 13, 1–2 (2014), p. 151.

106 See Breier, Bloody Sunday, pp. 176–91, for a detailed account.

107 Campbell, The Heart of Africa, p. 41.

108 See L.J. Bank, Home Spaces, Street Styles (London, Pluto Press, and Johannesburg, Wits Press, 2011) and Z. Blauw, ‘The 60th Commemoration of the Death of Sister Aidan Quinlan O.P.’ (unpublished pamphlet, 2012).

109 Interview with M. Breier, assisted by Z. Blauw, East London, 5 June 2017.

110 Meeting with Suresh Sivai, manager, Cambridge cemetery, East London, 3 June 2019.

111 WCA, ‘Minutes of Special Council meeting’, East London Town Clerk’s Office, Municipal Folder, Native Riots in East Bank Location, 3/ELN, 50/665/3/1,1343 (ELN TCO Native Riots).

112 Interview with M. Breier, assisted by Z. Blauw, Duncan Village, 20 April 2017.

113 Interview with M. Breier, assisted by Z. Blauw, East London, 5 June 2017.

114 Interview with M. Breier, assisted by Z. Blauw, Duncan Village, 20 April 2017.

115 WCA, East London Town Clerk’s Office, Municipal Folder, Native Cemeteries, 3/ELN, 50/31/7,1129.

116 S. Neuman, ‘Tulsa Race Massacre Investigators Say They’ve Sequenced DNA from 6 Possible Victims’, NPR (National Public Radio), 12 April 2023, available at https://www.npr.org/2023/04/12/1169464890/tulsa-race-massacre-dna-sequencing-mass-graves, retrieved 19 August 2023.

117 N.L. Clark and W.H. Worger, Voices of Sharpeville: The Long History of Racial Injustice (Abingdon, Routledge, 2024).

118 G. Lamb, ‘Mass Killings and Calculated Measures’, SA Crime Quarterly, 63 (March 2018) pp. 5–16.

119 G. Santayana, The Life of Reason: The Phases of Human Progress (New York, Charles Scribner’s sons, [1905] 1955), p. 82.