Abstract

This article considers popular political mobilisation in East London prior to the launch of the Defiance Campaign in the city in 1952, which ignited a racial war. It suggests that the failure of the municipal authority to assimilate urbanising Africans from regional mission stations and schools, especially in the 1940s, created a crisis of legitimacy for the white city fathers, who had previously promised to find a place for educated and ‘civilised’ Africans. As young, educated African elites were blocked from climbing the class ladder, despite the growth and prosperity of the city, and were prevented from escaping the congestion and filth of its neglected African locations, a strong sense of affinity was forged between them and the urban poor despite their cultural and class differences. This was intensified when apartheid-style laws were introduced that treated and prosecuted all Africans in the same racialised ways. After the African National Congress Youth League was established in the city, educated elites and ordinary people participated in a single set of protests against the municipal leadership around living conditions and their right to urbanise. This was framed by a strongly Africanist ideology, analysed here through a discussion of populism.

Introduction

This article considers popular political mobilisation in East London prior to the launch of the African National Congress (ANC) Defiance Campaign in the city in 1952, which ignited a racial war. It suggests that the failure of the municipal authority to assimilate urbanising Africans from regional mission stations and schools, especially in the 1940s, created a crisis of legitimacy for the white city fathers and ruling class which had previously promised to find a place for educated and ‘civilised’ Africans. As young, educated African elites were blocked from climbing the class ladder, despite the growth and prosperity of the city, and were prevented from escaping the congestion and filth of East London’s neglected African locations, a strong sense of affinity was forged between them and the urban poor despite their cultural and class differences.Footnote1 This was intensified when apartheid-style laws were introduced that treated and prosecuted all Africans in the same racialised ways, as lodgers, pass-law offenders, migrants and contract workers. In 1951, after the African National Congress Youth League (ANCYL) was established in the city, educated elites and ordinary people participated in a single set of protests against the municipal leadership around living conditions and their right to urbanise.Footnote2

I use the term populism in the analysis as ‘an ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogenous and antagonistic groups’, the ‘pure people’ and the ‘corrupt elite’, and which argues that power should reflect the general ‘will of the people’.Footnote3 For Africans in East London in the 1940s, the perceived corruption and deception of the white city councillors, who professed to offer trusteeship, implied that a return to African values and perspectives was necessary as a foundation for their struggle for freedom. Whites were seen as cunning tricksters, evil manipulators who created divisions among Africans, offering them false hope of progress through Christianity and education. Africans came to see this route as stripping them of their culture and putting them on a path that never seemed to lead to the destinations promised by the whites and, in the process, further divided the African nation. By the end of the 1940s, the idea of a ‘pure people’ being dominated and oppressed by a ‘corrupt elite’ shaped the views of many in the region. The turn to apartheid in 1948 illustrated how white oppression was akin to a revolving door from which there seemed to be no escape.

Cas Mudde further notes that populism presents a Manichean outlook, in which opponents are not just seen as people with different priorities and values, but are viewed as dishonest, corrupt and evil.Footnote4 The idea of compromise under this view is rendered impossible, since such action would corrupt the ‘purity’ of the people. Accordingly, populists do not seek to change the people themselves, but rather their status within the political system.Footnote5 In other words, populism does not necessarily require a drive towards improvement or modernisation, but merely the mobilisation of ‘the people’ against what is seen as an oppressive system. Paul Taggart notes that populist notions of the people are also usually associated with a ‘heartland’ – a place, or the idea of a place, where a virtuous, united population lives.Footnote6 Such a place may have geographical markers, but also represents an imaginary terrain of the people. Mudde and Ernesto Laclau also highlight the importance of a charismatic leader for populist mobilisation, which is often ideologically thin and requires an appeal to structures of feeling to awaken and galvanise groups of people who are perceived as being disadvantaged.Footnote7 In this understanding, political support is galvanised by sentiment.

Much of the literature on the ANCYL focuses on their ideological break with the older generation of Congress leaders and particularly their Africanist ideas.Footnote8 These formulations from the literature on populism add a useful dimension to this ideological analysis in conceptualising the sharp increase in racial tension and political mobilisation in East London in the early 1950s. I argue that this drew on a common structure of feeling associated with African experiences of land loss, soil erosion and proletarianisation in the Border region.Footnote9

The perception of the people as a relatively passive force waiting to be brought to life politically by a charismatic leadership was critical to the thinking of Border radicals in the 1940s. The ‘permanent persuaders’, such as Isaac Tabata and Govan Mbeki, who targeted the Transkei peasantry believed that this area beyond the Border represented the ‘pure people’ in some way – a population that was relatively uncontaminated by colonialism and was ready to rise. The African peasantry, Mbeki said, ‘has a short fuse’.Footnote10 An alternative vision was gradually formulated by Kaizer Matanzima, who wanted to restore those whom he saw as his Thembu tribesmen to a state of independence and sovereignty away from the enforced cultural influences of whiteness.Footnote11 In relation to the different forms of African nationalism that were advocated, it is worth reflecting on John B. Judis’s view that populist groups and leaders can just as easily be right- or left-wing.Footnote12 Similarly, Africanist ideas could just as easily be expressed through narrow forms of ethnic nationalism as through broader forms of African nationalism or pan-Africanism.Footnote13

This article examines the context and political approach of radical African nationalists, especially Ashby Peter Mda, a key member of the ANCYL. Mda envisaged that the University of Fort Hare could act as a nursery to turn Border radicals and young African nationalists into fully politically conscious activists. He often likened the role of Fort Hare in supporting the African nationalist struggle to that of the University of Stellenbosch in promoting the rise of Afrikaner nationalism.Footnote14 At the same time, unlike some of his compatriots on the Border, Mda was not looking for a pure, unblemished peasantry to restore the African nation. Indeed, as a Catholic, he was firmly against the restoration of tradition. He stated on several occasions that the egg of culture had been scrambled over two centuries, and that it would serve little purpose to begin to try to unscramble it.Footnote15 Mda’s core concern was the achievement of political freedom, democracy, land and sovereignty for Africans. Mda also felt that people would be most willing to rise in places where the pain and dispossession of colonialism was most intensely felt. For this reason, East London seemed to him an attractive location for the promotion of African nationalism, and a springboard for political mobilisation in the region and country as a whole.Footnote16

The Settler City Without Assimilation

Saul Dubow and Alan Jeeves have discussed the 1940s in South Africa not only as generating the forces that triggered the Afrikaner nationalist victory of 1948 but also as a period that offered other possibilities.Footnote17 Confronted with rapid African urbanisation, Jan Smuts’s United Party governments seemed prepared to loosen racial segregation. There were, however, many constraints: the key segregationist legislation on franchise and land, passed in 1936, remained in place. While the United Party included more liberal MPs, they were in a minority. If liberalism implies political rights, freedom of movement and land purchase on a non-racial basis, these remained well beyond its policy. The largely English-speaking white political leadership in East London in the 1940s offered little beyond white trusteeship that was insufficient to convince Africans of its benefits. The city was seen as the jewel of the Border, and the white population grew rapidly, especially after the Second World War. There were three main African locations: West Bank next to the harbour, which housed a few thousand dockworkers and their families; Cambridge, created to serve the labour needs of the white suburbs; and East Bank, which was the heart and soul of African urban life.Footnote18

East Bank was created by the city council in the late 19th century as a village of neat rows of traditional thatched rondavels.Footnote19 The location was bounded on one side by Church Street, which boasted a range of mission churches and primary schools, and on the other by the Kwa-Lloyd offices. In the early decades of the 20th century the area had been ruled by township administrator Cecil Lloyd, who governed with a tight rein and insisted on discipline and orderly behaviour.Footnote20 During this period, the residential sites were modernised and some basic services were provided. A post office and administration block were erected and white officials managed the location’s affairs with the co-operation of members of the local educated elite, such as Dr Walter Rubusana, through a Native Advisory Board.Footnote21 Many of those who settled in the East Bank in the early part of the century were Mfengu or migrants from the Kat River settlement, some of whom were classified as coloured. In recognition of the Mfengu community’s contribution to the colonial project, the city celebrated Mfengu Day each year on 8 May, allowing parades to take place on the streets.Footnote22

The rise of the Industrial and Commercial Workers’ Union (ICU) in the city under the leadership of Clements Kadalie in the late 1920s and early 1930s provided a voice for the workers of the East Bank location, who pushed the city council for improved living conditions.Footnote23 The development of the locations then proceeded at some pace before coming to an abrupt halt during the Great Depression of 1933. In 1934, the last of the new residential sites were granted in the East Bank and it would be more than a decade before any further sites were made available. All new arrivals had to be accommodated in the yards or through residential extensions to existing buildings. The population of the East Bank grew from around 20,000 people in the mid 1930s to 35,000 by 1945, and well over 40,000 by 1951.Footnote24

The main sources of the influx were the Ciskei reserves and part of the southern Transkei where rural livelihoods were fragile. At the time, the location social worker who surveyed the population, David Bettison, reported that while adult men went to the mines and the Witwatersrand, women, and boys who were too young for the mines, flooded into the city. Single women with children liked to come to the city because they could leave their children with their parents in the rural areas and still visit them regularly.Footnote25

In 1949, amid growing concern about the state of overcrowding, poverty, crime and disease in the city’s locations, especially in East Bank, a formal commission of inquiry was established by the municipality under the leadership of former Transkei official Hamilton Welsh. He did not share the views of the apartheid government on urbanisation and tribal development, but was a protagonist of the anglophone paternalism that guided a generation of Eastern Cape officials in the Native Affairs Department. These views were expressed by some of the English-speaking supporters of former Prime Minister Smuts and his United Party, which dominated the white political scene in East London.

In preparing for the commission, Bettison, who had clearer liberal sympathies and was concerned about the conditions in the locations, raised funds for a comprehensive social survey to be undertaken by 22 students from Rhodes University. Bettison was keen to inform the direction taken by the Welsh Commission and place its assessment on a more scientific footing. The Welsh Commission heard from different groups and delegations, including the Location Youth Association, African teachers and the Native Advisory Board, as well as municipal health officials, the police, the location superintendent, municipal law enforcement and the Native Commissioner in East London’s Native Affairs Department, J.G. Pike.Footnote26 The Commission’s remit was confined to gauging the views of civic bodies and municipal officials and did not extend to include representations from African political organisations, such as the ANC or the All African Convention (ACC).

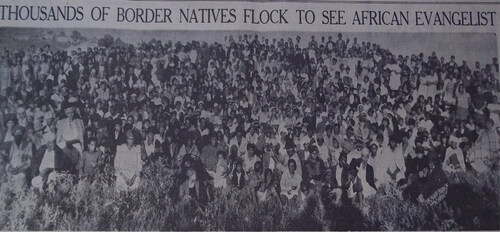

Bettison and his team reported that they were not well received in the township and that there was a lot of resentment towards whites and towards the white-run municipality.Footnote27 The survey showed that social welfare and health conditions in the township were appalling and that almost one-third of the people there were unemployed. At the time, the municipality aimed to replace the existing ramshackle, rusty wood and iron houses in the locations with new, semi-detached municipal houses. However, the East London City Council managed to build only 600 such houses for Africans in the 1940s (), compared with the municipal authority in Port Elizabeth which built 8,000. Indeed, conditions in East London’s locations were described by the Commission as ‘the worst in the Union’.Footnote28 In 1954–1955, when Philip Mayer and his team from Rhodes University started working in the Xhosa in Town project, he reported a similarly hostile reception and decided that it would be better to work through local Xhosa-speaking African fieldworkers than to try to do too many of the interviews in the township himself.Footnote29 Two decades earlier, Monica Hunter also reported that her links with the educated elites through her family’s missionary connections, which had resulted in fieldwork access in other areas, did not carry the same weight in East Bank.Footnote30 To gain access, she required the endorsement of Clements Kadalie, leader of the Africanist Independent Industrial and Commercial Workers’ Union.Footnote31

Figure 1. In the late 1940s the East London City Council built 600 municipal houses (right), while the majority lived in squalid conditions (left). (Source: Daily Dispatch, 11 March 1949.)

The Welsh Commission heard that virtually nothing had been done to improve the locations over the previous decade, during the tenure of location superintendent John Cooke, who allegedly seldom went into these areas. It found a shocking level of overcrowding: an estimated 1,700 of the 1,900 residential sites had additional rooms filling their yards. There were about 20 people living on almost every plot, averaging less than 200 square metres. Photographs showed that some residents even lived below the floorboards of houses, which was also a common place for shebeen queens to hide their liquor. Lodgers comprised three-quarters of the population of the location, or around 32,000 people.Footnote32

Those who controlled the sites and had permission from the municipality to build on them benefited significantly from the rents they received. The average rent per home was around 14 shillings, meaning that landlords could make between three to four pounds a month from rent, more than half the average industrial wage of around seven pounds a month. Landlords also capitalised on their property ownership by selling food and liquor to their tenants, which could enable them to double their rental earnings. There was little reason for landlords to seek employment in the city, as they could live off the income they could generate from their properties. Wages in the city were notoriously low, below subsistence levels, because employers applied assumptions of rural support from workers’ families.Footnote33

Only a couple of hundred middle-class families earned enough to maintain a decent lifestyle without lodgers. Nurses, teachers and African policemen reported that they earned over £20. One teacher at Welsh High School earned £45 a month by combining his salary with the income from renting out his yard. Clearly, the African population in the East Bank was not uniformly poor and the control of sites was a significant factor in shaping class divisions.Footnote34 However, the residential sites had all been allocated before the mid 1930s, which meant that the older families dominated the location, while new arrivals formed a rent-paying working class and underclass who were open to exploitation. This was particularly galling for the minority among them who were relatively well-educated and expected more opportunities and better access to housing. These young, aspirant middle-class individuals and families, who could not find decent, affordable accommodation, were particularly critical of the city council and tended to gravitate to the ANCYL.Footnote35

Conditions in the locations were appalling for all classes, pointing to a shocking dereliction of duty by the city council, which had collected rent from property owners but invested nothing in service improvements. A few communal standpipes and a handful of communal toilets served the entire location of about 40,000 people. There were no tarred roads, pavements or streetlights, and sewage ran in open drains on almost every street. One-third of all new-born babies in East Bank died in their first year, largely because of the unsanitary conditions: tuberculosis and venereal disease were rife.Footnote36 The Commission heard that there was an especially high rate of migration into the city by boys and young men between the ages of 16 and 24, most of whom were unemployed. Some moved around in groups or gangs, preying on migrant workers and terrorising local people in the location, even threatening whites in town. Sticks and knives were used in fights between gangs.

Henry Tyamzashe, part of the old guard in the ANC, wrote to the press in 1950 to complain about the ‘lack of sane administration’.Footnote37 The Location Advisory Board, on which he had served, was a nomgogwana (kindergarten) wasting its time, while ‘the so-called “City Fathers”’ look sedulously after the interests of Europeans’. The welfare and health conditions in the locations were a threat not only to Africans, but to the entire urban population. He was perplexed that the police seemed only interested in arresting and fining shebeen queens and informal traders, while the real criminals, the tsotsis (young gangsters), roamed free. He implied that this was lucrative for the police.

Tyamzashe called on the new superintendent, R.T. Venter, to immediately attend to the lavatories, install streetlights and build cement runnels to channel sewage away from the streets. He also asked for the locations’ water not to be drawn from boreholes, which were unclean, but to be connected to the city’s main supply, which came from large modern storage dams. Tyamzashe said that he fully supported the Welsh Commission’s recommendation that a new ‘headman system’ be introduced to supplement the existing police force in an effort to restore law and order. He also advocated the creation of a loan scheme which would allow educated families to build new houses for themselves on land beyond the existing locations, while those in the locations should be encouraged to improve their homes. W.D. Ntloko, brother of Cecil Ntloko, a lecturer at the University of Fort Hare, and a history teacher at the local high school, said that the East Bank was now like a ‘Frankenstein Monster’, created by the city but no longer under its control.Footnote38

The nature of policing in the location, touched on by Tyamzashe, was a major issue of discussion at the Welsh Commission. Cornelius Fazzie, a leader in the ANCYL, complained to the Commission of police violence and abuse. New apartheid laws, he said, placed the onus on location residents to be in possession of their papers at all times. This requirement, he insisted, resulted in his arrest, which had turned ugly when white police officers started to beat him for no reason. He had not been found guilty of anything, but beaten, he said, just because he was black, like ‘others at the prison’. This practice was widespread and systemic and he urged Commissioner Welsh to make a concerted effort to ‘kill this culture of violence and disrespect in the police force’.Footnote39

Members of the local police force, by contrast, suggested that one solution to this vicious cycle was to remove unemployed and criminal youth from the city altogether.Footnote40 The new apartheid policy on urbanisation sought to force those who did not have work in the city to return to the reserves where they could be disciplined by traditional leaders. Although Welsh did not recommend this solution, he did advocate better control over urbanisation and acknowledged that there was a crisis of decency and respect. He urged the city fathers and whites generally to take responsibility for better assimilating Africans, creating new opportunities especially for educated Africans and their families. This would develop a strong, positive sense of urban citizenship.Footnote41 Welsh also recommended a new hospital, schools and other educational facilities, community halls, sports facilities, a crèche, and better bus services, including to the beach. Nutritional support for the poor should be improved, including through the introduction of food gardens. New jobs should be created for those who had completed their high school education, funded by the rates and fines paid by Africans, some of which were being directed to other municipal expenses.

A cornerstone of Welsh’s recommendations was to improve slum conditions. He did not feel that property owners should be denied the opportunity to generate rent. Rather, he thought that wages were generally not high enough to stimulate a property-owning middle class unless they were provided with the opportunity to supplement their earning through rental income. The solution was to increase the number of new houses available for the emerging small black middle class and the industrial working class. This would require the allocation of new land, an increased budget for housing, and access to loans for Africans to build their own houses. Urban youth should be assimilated through organised sport, music, scouting and similar activities. Two new community halls were built with support from the National War Memorial Foundation (NWMF); Rotary helped to raise funds for a third to honour Clements Kadalie, who died in 1951.

Kadalie had proposed that the municipality empower the representatives of the Location Advisory Board to make improvements in their own neighbourhoods. This would also increase the legitimacy of the municipality and the Board, and potentially reduce the culture of racial animosity, mistrust and non-cooperation. In effect, the Welsh Commission reprimanded the white city fathers for failing to recognise their civilising role and responsibility to Africans in the city. In response, the city council asked who was going to pay for the improvements. Welsh also suggested a closer integration of the city’s responsibilities and those of the Department of Native Affairs. At that stage, there was little chance that the central government would fall in line with the more socially inclusive recommendations of the Welsh Commission.

Masculinities, Stick Fighting and White Fragility

The city authorities, police, Welsh and Bettison were all anxious about young African men and teenagers in the city and the difficulties of absorbing them. Reports bristle with references to the posturing and performance of traditional masculinities brought to the town from the countryside. In her work on rural masculinities in the 1940s, Anne Mager, drawing on the ethnographic work of Philip Mayer, Iona Mayer and Percy Qoboza on youth socialisation in the former Ciskei and Transkei, suggests that during the Second World War and immediately afterwards the nature and form of stick fighting in parts of the rural Eastern Cape changed significantly.Footnote42 She argues that over this period increasing household poverty and massive male out-migration to the mines had left youth unmanaged in the rural areas. The disintegration of some of the regulatory mechanisms for youth socialisation, such as careful control and refereeing of stick fights, led to an escalation of violence, both between men and towards women.

Mager suggests that youth and village factional conflicts transformed stick fighting from a sport back into a form of local warfare, and that the number of those killed rose as a result. Cases of increasingly violent and unregulated stick fighting filled magistrates’ courts in the 1940s. Deaths caused by this fighting were dealt with as cases of public violence, which usually led to the offenders being caned by the police or fined, and then released. Repeat offenders were gaoled with hard labour. While mothers and daughters would occasionally follow the combatants into battle, ululating in support, Mager notes that violence was also directed at women – one of the reasons why they fled to the cities.Footnote43

In East Bank location, traditional stick-fighting skills were greatly admired by the youth who had recently come to the city.Footnote44 Many participated in regular weekend bouts in the woods behind East Bank, arranged between youth from different rural areas. Senior migrants were involved in recruiting teams of fighters and acted as referees. Ironically, the senior presence that was sometimes missing from stick-fighting battles in the countryside was present in the city, ensuring that the rules were obeyed and moderation prevailed. Organisers also wanted to avoid exposing themselves to police scrutiny and ending up in court having to explain why young men were dying. As one migrant explained: ‘We looked forward to the stick fighting at the weekends. It was a topic of conservation at the beer drinks during the week, but we also knew that the sport would be shut down if youth died, so we made sure everyone played by the rules’.Footnote45

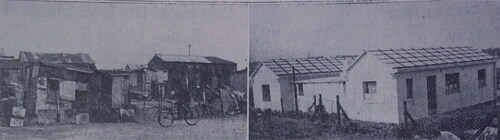

In 1951, 77 young men from the Mooiplaas and Kwelera rural locations just outside East London appeared at East London magistrates’ court after a youth, Namla Makala, died during a stick fight in September 1950 ().Footnote46 The Mooiplaas group were found to be the aggressors and each fined £10 or given three months’ hard labour, while the Kwelera youth were each fined £5 or given one month’s hard labour. The young male defendants were photographed () in their fighting regalia and appeared in court as if ready for battle. Sixty of the youths’ fines were paid (), and 17 went to gaol.

Figure 2. Mooiplaas and Kwelera youth in East London appear at the magistrates’ court after a youth was killed in clashes between the youths of the two rural locations. (Source: Daily Dispatch, 24 January 1951.)

Figure 3. Youth pose in their fighting gear in a studio photograph taken in East London in 1949. (Source: Daily Dispatch, 14 June 1949.)

Figure 4. Parents and relatives of the Mooiplaas and Kwelera youth work together to raise money to pay the fines that will enable their sons’ release. (Source: Daily Dispatch, 24 January 1951.)

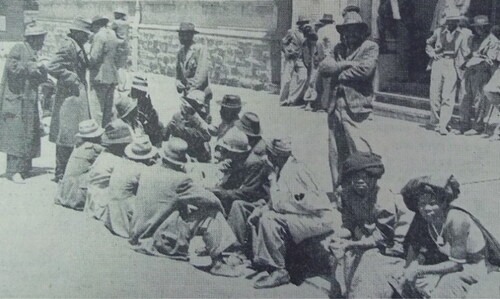

Given that the city had no system for absorbing urbanising youth through appropriate schooling, casual work or others forms of socialisation, the young men clung to networks from their home areas and idealised the culture of stick fighting and masculine combat. The appetite for rituals of violent masculine rivalry was also evident in the enormous popularity of boxing in the locations. Youth tended to move around in gangs with friends of the same age, dressed in city clothes (). The city council and the police described them as ‘hooligans’ or ‘juvenile delinquents’.Footnote47 During the drought of 1949, large numbers of youth arrived from the Queenstown area and Thembuland, further than the normal catchment area for the city. The men from these areas were known to be tough and usually preferred to go to the mines.Footnote48

Figure 5. The contrast between country boys in traditional gear (left) and the new city styles for young men (middle). The transition from one to the other was considered to be a major cause of social pathology and political instability, as young men were caught between the worlds of tradition and modernity. Captions in italics (right) from the Daily Dispatch, 24 January 1951. (Source: Daily Dispatch, 24 January 1951.)

Local residents recall that many of the new arrivals settled in the yards of Thulandiville, on the edge of the location, and soon won a reputation as the most feared tsotsis and knife-fighters in the East Bank.Footnote49 They also knew the tsotsi styles from the Reef better than the locals because the Queenstown area was a strong supplier of migrant labour to the mines. It was said that many of the most fearless champions in the new community halls came from the Queenstown area.Footnote50 The popularity of boxing in South Africa can be traced back to the combative culture of masculinity in East Bank in the 1940s.Footnote51 Although it was unusual for youth violence to be directed against whites, there were examples of this, for example at St Michael’s school in Keiskammahoek and in the city as well. These forms of mobilisation and masculinity were to play a role in racial violence which erupted after the launch of the ANC’s Defiance Campaign in East London.Footnote52

White Responses

The municipality and some white organisations seemed to take a new direction in response to Welsh, funding new community halls, feeding schemes and healthcare programmes for children, as well as talking about upgrading East Bank. The council planned an extension of 150 new houses in the short term and appointed a new superintendent for the city’s locations.Footnote53 African musicians were invited to play in white clubs on the beachfront, while sports clubs and boxing were supported in the townships.Footnote54 Black residents were able to join plays and eisteddfods in the City Hall.

The latter concession caused a great stir, particularly when boisterous behaviour accompanied the victory of the black team from Welsh High School in a regional choir competition that was a central event in municipal civic life. Letters poured into the newspapers questioning the wisdom of opening the hallowed City Hall, the heart of white authority and settler tradition in East London, to Africans, who were described as dirty and disease-ridden.Footnote55 While some white councillors objected, the more liberal lobby defended the decision by Mayor E.H. Tiddy, arguing that since Africans paid rates and levies in the city, they had every right to use the City Hall.

The older generation of African politicians were encouraged by the new developments. They included R.H. Godlo, president of the Location Advisory Boards’ Congress of South Africa, and Kadalie, who had joined the Native Advisory Board by the late 1930s. They had complained bitterly of living conditions in the locations, although they actually lived in the neighbouring, racially mixed suburb of North End. ANC member Tyamzashe, who lived on Church Street in the Tsolo section of East Bank, welcomed the new initiatives for social inclusion that seemed to promise more liberal policies. This optimism was clearly reflected in improved turnouts for the elections to the Location Advisory Board in 1950, when about 2,000 East Bank adults cast their votes.Footnote56 On 11 April 1950, the NWMF opened the Duncan Village Community Centre, which could accommodate 300 people. Over 100 whites attended the ceremony, at which it was explained that NWMF social workers would supervise many activities there, including debates, cinema shows, concerts and important lectures on home economics and health. One of the social workers was the multi-talented musician and band leader Eric Nomvete, who collaborated with welfare organisations to create opportunities for African cultural life and well-being in the city.Footnote57

A vegetable club would also be established, as well as a crèche for 50 children. The East London Technical College also announced it would run evening classes in adult literacy and that a new primary school would be built for 500 African children at a cost of £25,000.Footnote58 There seemed to be plenty of evidence that, despite apartheid, the city’s liberals had taken the recommendations of the Welsh Commission to heart and were doing what they could to make up for decades of neglect. The new spirit of reconciliation was illustrated in 1950, when 500 whites attended a church service led by the well-respected Methodist minister, Reverend Seth Mokitimi from Healdtown.Footnote59

At the same time, the rise of the Torch Commando in the city and its campaign against the unconstitutional removal of coloured people from the Cape voters’ roll also seemed to indicate a commitment to a progressive liberal agenda.Footnote60 The Torch Commando mobilised whites across the Cape and garnered particularly strong support in the Border. A major rally was held in East London in March 1951, with convoys of Second World War veterans coming from every part of the region in a show of unity against Afrikaner nationalism. The Daily Dispatch reported that ‘the centre of the city was throbbing with life’.Footnote61 About 3,000 ex-servicemen and women, wearing medals and ribbons, formed detachments, holding flaming torches aloft. They marched to the City Hall singing old army songs. Banners read: ‘[d]own with slavery, fight for your rights, the game is on, out with Nazism, up the democrats, we say hands off the constitution’.Footnote62 But despite the diverse political elements under the Torch Commando umbrella, the six elderly white East Londoners I interviewed saw the celebrations of the Allied victory through the streets of East London at that time as an expression of white solidarity that made no reference to the suffering African majority in the city.

In the days that followed, letters poured into the newspapers complaining that the nationalist fervour of the white settlers did not include or acknowledge the rights and contribution of Africans in the city. To rebut these claims, it was stated in the media that the Torch Commando was essentially a civic movement and not a political one. Yet one letter stated that the movement was ‘for a progressive allied and English white rule, which will be fair, while upholding white supremacy’.Footnote63 It was a movement that made no effort to acknowledge the contributions of black people to the development of the region, or to the Allied war effort to defeat Hitler.

A.P. Mda, the University of Fort Hare and African Nationalists

A.P. Mda was committed to a very different route. By the mid 1930s he had worked his way through an early infatuation with liberalism and mission Christianity – he was a devout Catholic – and arrived at the conclusion that African freedom would not come through the prevailing version of settler trusteeship or white liberalism.Footnote64 A radical activist and a founding member of the ANCYL in Herschel district, Mda befriended ANCYL students at the University of Fort Hare, including Robert Sobukwe and Godfrey Pitje, and turned them against the older generation of political stalwarts.Footnote65 The rift led to a vote of no confidence in Zachariah Keodirelang Matthews as president of the ANC in the Cape.Footnote66 Henry Makgothi, who was secretary of the ANCYL at Fort Hare, said that there was real animosity on the part of the students but for ‘the professor, that didn’t ruffle him. He took it in his stride. He was a very level-headed person’.Footnote67

It seems clear that Mda and Matthews were on a collision course, which ultimately centred on the perceived role of the University in the African nationalist struggle. Mda felt that the University had to act as a kind of Trojan horse within the South African academic establishment, producing activists and soldiers who were intellectually and politically prepared to implement the ANCYL’s programme of action, lead the liberation struggle and take over the country.Footnote68 Mda repeatedly stated that Fort Hare had to be for the Africans what Stellenbosch University had been and continued to be for Afrikaners – a training ground for assuming and managing state power. Matthews, however, did not see things in such instrumental terms and, as a result, was seen by Mda as a reactionary force obstructing the path to freedom for Africans.

Mda was not a traditionalist who felt that African societies should be restored to their ancient cultures and ways of life or that whites be driven into the sea.Footnote69 He accepted that British colonialism had made an indelible mark on the Border region in the Eastern Cape, producing far-reaching, irreversible cultural change and that there was no way Africans could or should return to the imagined bucolic bliss of an earlier era. They needed to take what was of value from western culture and incorporate it, but under a newly configured nation state run by black Africans and not by settlers of European descent, Indians or coloureds. The South African nation would not exclude whites or other races, but it would be a place where the spirit of Africa prevailed and the dominant ideology would be one of African nationalism.

The Africanist politics of Mda, like those of Tabata, were principled and uncompromising because they were based on a clear understanding of the logic of elimination propounded by settler colonialism. Mda expressed this in an article published in Bantu World in 1941, in which he explained that western civilisation – which may be understood to mean settler colonialism in this context – had created a revolution in native life.

One only has to think of the fate of the Red Indians and the South African bushmen to realise the Herculean struggle within which the African has been engaged to adapt and adjust himself to Western culture which accepts no compromise but presents only two alternatives: the complete extermination of weakly and hesitant recipients or the wholesale acceptance of it all and what it stands for. The African is struggling to master the new situation and in some respects, he is succeeding and is going to succeed.Footnote70

Mda felt that neither complete extermination nor wholesale acceptance could ever be an option for Africans and that the correct course of action would entail struggle – armed struggle if necessary – to prevent Africans from being enslaved, de-cultured and exterminated. Mda felt that a plan of direct action against white supremacy was necessary even before 1944, when the ANCYL was launched. During the 1940s, he pushed his political position through ‘backroom work’ in the ANC.

Mda’s politics were built on the idea of the ongoing threat of genocide and he saw the advent of apartheid in 1948 as an absolutely critical moment for Africans, one which renewed the threat of physical extermination, necessitating a move towards armed struggle.Footnote71 Although politicisation was crucial, the time for slow politics had passed with the arrival of racial fascism, and direct action against the state was needed immediately to prevent the African cause from losing ground. He wrote to Pitje, a senior graduate student on the lecturing staff in the African Studies Department at Fort Hare, saying that the University was just the place to start a branch of the ANCYL.Footnote72 The young people there were the intellectual leaders of the future and a growing consciousness of their role in the national liberation struggle would add new vigour and force to the drive towards national freedom.Footnote73 Mda also communicated directly with Sobukwe, who was a rising star in the student movement at the University, and others, to establish the Victoria East ANCYL branch in Alice in November 1948.Footnote74

The Africanist students in the ANCYL were strongly in favour of non-collaboration and instigating more radical political action, such as strikes, public protests and boycotts. The location of ANCYL off campus at Victoria East also allowed the leadership to forge relations with the nurses at the Victoria Hospital, whom they encouraged to strike in 1949. This connection was strengthened through the close social connections and romantic ties between some ANCYL leaders and nurses. Sobukwe was being courted by all parties and stood apart from Z.K. Matthews, becoming closer instead to Cecil Ntloko, linked to the Non-European Unity Movement, in the African Studies Department. Joe Matthews, a student active in the ANCYL, said that the atmosphere became electric as students began to believe that there could be ‘freedom now, and freedom in our lifetime’.Footnote75 This was exactly the atmosphere that Mda wanted to create as he encouraged the students to take their energy beyond the campus. At the same time, the ANCYL’s programme of action, which he conceived and promoted, was accepted at the 1949 conference, laying the foundation for the Defiance Campaign of 1952.

Taking the Revolution to the City

Mda believed that revolutionary action was needed to oppose what he saw as apartheid’s attempt to perpetrate racial and cultural genocide – action that could, he thought, be ignited by connecting his motivated young acolytes with the urban and rural poor. Mda had established a branch of the ANCYL in Herschel in the mid 1940s, the first in the Cape, focusing on activating Africanist sentiment. Rural districts like Herschel, Xalanga and Glen Grey were fertile ground for mobilisation.Footnote76 Successive waves of colonial political and economic restructuring had left them in a state of dire poverty by the 1940s. Young men could see how their fathers had been defeated and demoralised and were determined that this would not happen to them. Mda worked tirelessly, moving around the area and trying to draw youth closer to him and the ANCYL’s ideology. This was the same area where Matanzima was building his own political strategy. However, Mda also realised that there was great, if not greater, political potential to be found in the region’s urban areas, where poor people were flocking during the 1940s with literally nothing to lose.

Mda had worked in East London as a gardener in the 1930s after he had failed to find a teaching job. Partly as a result of his own experiences, he understood East London’s uncompromising white settler ethos. On a personal level, he had experienced its refusal to assimilate Africans when he had arrived there with a good qualification but could only acquire a menial job. He had also experienced the poverty of the city’s locations, as well as the dominance of old-school, moderate African nationalists among the elite.

Mda encouraged the Fort Hare radicals, especially those from the Border such as Sobukwe and his friend Dennis Siwisa, to form a vanguard in the city to mobilise Fort Hare graduates, teachers and students, as well as other influential figures with close links to the people, such as religious and squatter leaders.Footnote77 Through Sobukwe and Siwisa, contact was made with Cornelius Fazzie. He had been educated at a Methodist mission school, played rugby at a high level, trained as a teacher and rose to prominence in the late 1940s through his outspoken criticism of the municipal authority.Footnote78 Both Sobukwe’s future wife and Fazzie’s wife had been nurses at Victoria Hospital and were close friends, which tightened this bond. The networks around the mission school elite intersected in complex ways, often via the town of Alice, home of Fort Hare and Victoria Hospital, which trained nurses, with Lovedale and Healdtown schools nearby. Some of the nurses took up positions at Frere Hospital in East London.

A second key person in the East London ANC was Joel Lengisi, a quiet young man who had come under Mda’s influence in Xalanga district, which was sending an increasing number of migrants to the city in the 1940s. The final member of the leadership group was Alcott Skei Gwentshe, son of parents who were Israelites and refugees from the Bulhoek massacre.Footnote79 Gwentshe was not mission-educated, but was an outstanding rugby player, a well-known jazz saxophonist and a charismatic public speaker. Sobukwe realised that he had the common touch needed for the ANCYL to win support in the townships, as well as being a close associate of Fazzie, who also came from the Queenstown area. These three individuals, known as the triumvirate, formed the leadership core of the ANCYL in East London in 1949 and achieved popularity through their action-orientated politics of non-collaboration and protest.

The Fort Hare students were role models for matriculating pupils at Welsh High School in East Bank where Cecil Ntloko’s brother, Sobukwe’s mentor at Fort Hare, was the senior history teacher.Footnote80 The students were also active at the Rubusana sports ground and local community halls during the weekends, turning sports events and Sunday socials into political recruitment and education sessions. These dynamics encouraged Mda to establish a Bureau of African Nationalism in the city, which produced a bulletin to promote the ANCYL’s programme of action. Mda was so confident in the city’s role as a political home for African nationalism that he sponsored the project out of his own pocket. His interventions were successful and lasting.

Within the ranks of the ANC, the old guard were openly challenged by younger African nationalists and radicals. The school, which had been founded in the early 1940s, oversaw the education of 380 secondary school pupils, about 100 of whom were ‘passed out to work each year’, leaving at different levels. Every year, between 300 and 400 students from across the region applied for admission to the 100 or so available places, with applications from East London prioritised. W.D. Ntloko and others at the school helped to produce an elite group of highly politicised students.Footnote81 The leadership of the ANCYL at Fort Hare, especially Sobukwe, were heroes at Welsh High School and more generally in the location in the late 1940s.Footnote82 They were admired for standing up to disciplinarian, Eurocentric white managers and teachers at schools like Healdtown and St Matthew’s and at the nursing colleges.

Ironically, Fort Hare ANCYL leaders could use the new city facilities to train and politicise young activists from the township. Former members of the early ANCYL emphasised in interviews that the new community halls and Rubusana sports ground were critical spaces for political mobilisation.Footnote83 Fort Hare students would come to the city over the weekend to watch rugby, listen to jazz and attend the activities organised at the Bantu Social Centre.Footnote84 The students would then leverage their attendance at, and participation in, these activities to recruit members to the ANCYL and promote the basic ideas and principles that informed the programme of action.Footnote85

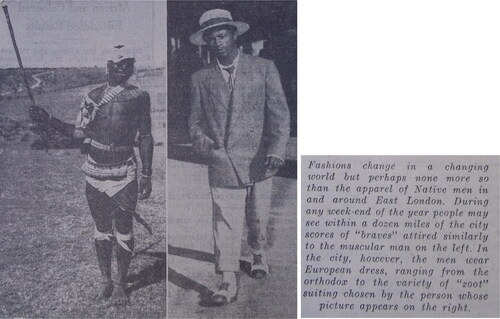

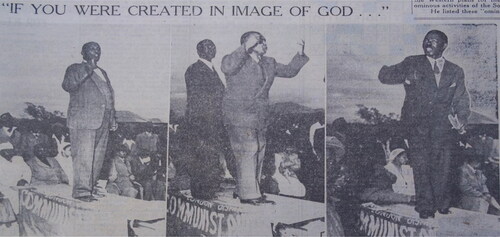

The Africanists were, however, not the only faction in the ANCYL. Nationally, there was strong support for the Communist Party, which had also mobilised at the provincial level in the Eastern Cape at Port Elizabeth. However, the party faced difficulty gaining a strong foothold in East London. A rally was organised for general secretary Moses Kotane in June 1950 to protest against the Suppression of Communism Act ().Footnote86 The turnout was disappointing. Kotane told the crowd: ‘If you believe that you are created in the image of God, then you cannot believe you must be suppressed by the white man’. He went on to say that Afrikaner nationalists were banning the communists because they ‘just want cheap labour from the Transkei and Ciskei’ and ‘we come to talk to you about higher wages and decent conditions … they don’t like that’.Footnote87 In the same month, Walter Sisulu, secretary-general of the ANCYL, also visited the city to encourage a wider alliance against the passage of the Suppression of Communism Act ().Footnote88 His efforts also seem to have had a limited effect, although he did address an ANC rally in the city. Significantly, when the only communist on the Native Representative Council, Sam Kahn, came to East London, he was told by the local ANCYL that native representatives were not welcome in the location – even if they were communists.Footnote89

Figure 6. Moses Kotane, general secretary of the South African Communist Party, speaks at a mass meeting organised by the East London branch. He was joined by local members of the party at an event which was not that well attended. (Source: Daily Dispatch, 12 June 1950.)

Figure 7. Walter Sisulu addresses ANC followers in a house in the East Bank location ahead of the passage of the Suppression of Communism Act in June 1950. (Source: Daily Dispatch, 10 June 1950.)

In this period of mobilisation and charismatic leadership, it is noteworthy that there was also considerable support for Nicholas Bhengu, a spiritual healer with the Assemblies of God, which was initially a Zulu church ().Footnote90 Bhengu argued that freedom and dignity would not come through the ballot box or through material improvements in people’s lives but through the world of God and a realignment of people’s individual moral compasses and spirituality. He claimed that township poverty and common illnesses indicated the extent to which people had lost direction and that they needed to return to God’s ways in order find salvation. An itinerant Zulu preacher from Natal, like Wellington Buthelezi in the 1920s, Bhengu was not an advocate of Xhosa tradition and broadly rejected African traditional values. Instead, he preached a gospel that was influenced by Garveyism and African American churches. He said that he could heal those who came to his church and were prepared to reform their lives. People claimed he could heal the sick and make cripples walk again, and many followed his crusade. A populist, charismatic leader, Bhengu had his own way of appealing to those affected by the soul erosion of colonialism. He encouraged black consciousness and promoted his own version of African Christianity but did not align with the view that the future was about the restoration of local African cultural traditions or with political movements.

The ANCYL and Lodger Permit Fees

This article opened with a discussion of populism. In contrast to Gramsci, who stressed the importance of historical experiences as the basis for political affiliations and alliances, Laclau argued that political discourse itself could play a much larger role than many Marxists had acknowledged in manufacturing connections between groups and factions which might otherwise remain separate.Footnote91 He also discussed how differences among groups might be dissolved through ‘new articulations’ by populist politicians striving to create blocs of opinion which pit ‘the people’ against ‘the elite’.Footnote92

There were several lines of cleavage within East Bank location. Those identifying as Mfengu regarded themselves as early arrivals and mainly lived in Tsolo section. There was also a distinction between so-called Red and School residents, as numerous observers noted, between ethnic groups, and between those identifying as Xhosa who came from the Ciskei reserves and the Gcaleka who hailed from the southern Transkei across the Kei River. Residents who had arrived from Thembuland developed a strong identity in the location and organised sports clubs which often reflected their places of origin and tribal associations. Gender and generational divisions were also significant, as was the class distinction between lodgers and homeowners. In East Bank, most residential properties were controlled by women, who generally extracted rent from male migrants. They also controlled informal income-earning opportunities, such as selling food and beer. In the struggles over lodger permits and access to the location they mobilised to defend their interests. Leading ANCYL politicians like Gwentshe, a backyard dweller, championed their cause and earned their support. The flood of youth into East Bank in the 1940s raised their profile and political influence as they tried to carve a place for themselves in the city.Footnote93

Yet, despite all these internal differences, there was a common experience of racism in the city and the region, as well as a widely shared perception that the white settlers in the Border were only interested in looking after their own interests and wanted to see the elimination of African culture and tradition. The Africanists were able to tap into shared experiences of white supremacy and a common structure of feeling to create connections among the various groups, although the task was difficult before 1950 because of the divisions that existed.

The opportunity for a more united front was presented to the ANCYL in 1950 when the city council decided to raise the lodgers’ fee in the locations by 2 shillings per person a month to pay for some of the improvements suggested by the Welsh Commission. Lodgers were already paying exorbitant rents of between 15 to 20 shillings a month for substandard accommodation, described by observers as among the worst in the Union. Why, lodgers asked, did the city council not fix the locations before it started raising taxes to pay for such improvements?Footnote94 Why did it not seek more funds from whites and even their landlords, who made good money from renting? Lodgers outnumbered homeowners by four or five to one, and the shortage of housing in the location meant that many ANCYL members lived in the yards – either as the offspring of landlords or as independent individuals seeking accommodation in the city.Footnote95

Gwentshe himself was a lodger who lived with his young family in the yards. He was also one of the three leading figures in the newly created ANCYL. When the municipal authority called for the imposition of the new fee, he volunteered to become the face of a campaign opposing it. Accordingly, on 16 April 1951, the ANCYL organised a mass march to City Hall which was led by Gwentshe, carrying his saxophone. It was an orderly, peaceful demonstration supported by over 3,000 people. A petition was delivered to the city council rejecting the lodgers’ fee increase. The march placed the ANCYL at the centre of the struggle against what was presented as a racist, self-serving, greedy, corrupt and dishonest white council which only served white interests. The case against the municipality was strengthened by the revelation that the municipality had tried to implement the increase before it had been ratified by the council. This seemed to offer further evidence of the corruption of white power.Footnote96 By articulating a discourse of racial oppression around the plight of the lodgers, the ANCYL was able to unite residents across several divides. Rural and urban youth were equally affected by the fee increase, as were men and women. The young men in the ANCYL won the full support of women, traders and shebeen queens in their campaign against the new fee. The only group that did not support them were the property owners.

The march embedded the ANCYL as a catalyst in the mass politics of the township and changed the complexion of its role in the struggle in East London. It was now popular with the entire lodger community, which included many single women. The city council persisted with its efforts to make residents pay for improved services and housing reform. The ANC leadership and their followers, who felt they had much to gain from the housing programme, kept making alternative suggestions for raising funds, such as making homeowners pay more. However, the position of the ANCYL and the lodgers was that there would be no payment from anyone until the city had fundamentally improved the conditions for lodgers in the location. The municipality pushed on with its attempt to raise the levy, eventually managing to raise a few thousand pounds towards its target of over £20,000. However, realising that the levy would not work, the municipality eventually dropped the scheme, delivering a great political victory to the ANCYL.

Conclusion

When collecting oral histories on popular politics in East London in the 1950s, I found that discussions invariably shifted to the death of Sister Aidan Quinlan and the events of November 1952. People talked about what they thought happened on that day and the issue of the condition of her body. Mostly, they disputed the story that the nun was badly mutilated and her body used as muti.Footnote97 It is sometimes difficult to get a clearer picture of the wider currents and dynamics of the popular politics in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

Some academic literature has stressed the importance of sociological and cultural cleavages in the urban community. Anthropological studies of the city’s locations highlighted the historical divide between Red and School migrants as the most salient cleavage, although commented little on how this influenced the wider politics.Footnote98 John McFall, former news editor of the Daily Dispatch, wrote a book after the 1952 rising called Trust Betrayed.Footnote99 He believed that African people betrayed the trust and investment that the settler community and city fathers had invested in their development and well-being. On the evidence presented above this argument is difficult to sustain, but it is interesting that McFall identified populism as the main thread in the mobilisations of the early 1950s.

In the 1990s, Anne Mager and Gary Minkley launched a new strand of historical writing on the city. They revisited the Defiance Campaign through a careful reading of archive and newspaper sources and concluded that divisions of class, age and gender had a profound effect on popular mobilisation.Footnote100 Mager later expanded on the theme of gender inequality and politics in her book on the making of the Ciskei.Footnote101 In 2005, Lungisile Ntsebeza elaborated on the theme of generational divisions and youth sub-cultures in the city in the 1950, based largely on oral interviews.Footnote102 He highlighted how quickly generational division could become a political flashpoint. In 2013, Oliver Murphy wrote a thesis on the connected issues of race, violence and nation in the Eastern Cape. He argued that an Africanist strand to the politics of resistance gained considerable momentum in this period and came to shape resistance politics in more direct ways.Footnote103

The analysis in this article aligns with the work of Mager, Minkley, Ntsebeza and Murphy, showing how developments in the 1940s provided a solid platform for an Africanist populism to flourish, captured in the popular rally cry, Mayibuye iAfrica (Come Back Africa), which was widely embraced as the slogan of liberation.Footnote104 Interviews with Hamilton Keke and Malcolm Dyani, activists and Robben Island prisoners, highlighted the power of this slogan in stirring emotions and calling for action. Dyani explained of the time that:

[o]n Robben Island we learnt about politics in a new way, that is why we called it the University of African Nationalism. It was only on the Island that we [the Africanists] started to understand Marxism better, and the like, because before that we were responding to our oppression in an immediate and emotional way. It was more about an emotional response to oppression we felt in the East Bank location, where living conditions were so appalling … and where they would even pick us up at night and put us in trucks, like cattle, to be washed in public with chemicals to get the lice off our bodies and out of our hair.Footnote105

The argument here is not that that the cleavages and social divisions highlighted by other authors were unimportant or invisible. However, what is striking about the unrest that started to ferment around the lodgers’ protests in 1951, and especially with news that the city council and the state was attempting to turn the cost of collective urban reproduction back on the people, was the sense of unity of purpose. When D.M. Nginza, an African clerk in the municipal offices, reported this deceit to the ANCYL leadership it immediately became a source of popular mobilisation.Footnote106 Nginza himself said that it made him famous, as a hero of the struggle.Footnote107 It was the issue that turned the crowds and offered political clarity. Everyone was affected, landlords would pay more, tenants would suffer, and the settler state had again ‘tricked the people’, a classic tactic of English settler trusteeship in popular discourse.Footnote108 They promised reform and then planned to make the people pay for it. The intended and actual violence against whites and police during these protests was significant.Footnote109

Many in East Bank came to the same conclusion when the state and police massacred their people in 1952 and whites could only talk of the evil that had been done to the body of a virtuous nun. There were subsequent moments when other divisions, both political and socio-economic, came bursting to the forefront, such as when older men took to the streets with their sticks in 1958 to stamp out ill-discipline and disrespect among the youth. But, shortly after these events, the ANC leadership in East Bank resigned from the ANC to join Sobukwe and the PAC breakaway faction.Footnote110 As veterans recall, East London was the only place in the country where the entire ANC leadership joined the PAC in this way.Footnote111 Stalwarts from the Defiance Campaign, like Fazzie, led the charge. In the five years that followed, the PAC developed a considerable following in the city precisely because it developed strategies that could bridge the cultural and political gap between youth and elders, between townsmen and migrants, and present a politics of the people – an Africanist and populist politics of liberation.

Visiting Professor of Anthropology, Walter Sisulu University, Nelson Mandela Drive, Mthatha, South Africa. Email: [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8506-7401

Notes

1 See E.L. Nel, ‘Racial Segregation in East London’, South African Geographical Journal, 73, 2 (1991), pp. 60–8; D. Atkinson, ‘Cities and Citizenship: Towards a Normative Analysis of Urban Order in South Africa, with Special Reference to East London, 1950–1986’ (PhD thesis, University of Natal, 1991); G. Minkley, ‘Border Dialogues: Race, Class and Space in the Industrialisation of East London, 1902–1963’ (PhD thesis, University of Cape Town, 1994); L. Bank, Home Spaces, Street Styles: Contesting Power and Identity in a South Africa City (London, Pluto Press, 2011).

2 A.K. Mager, Gender and the Making of the South African Bantustan (London, Heinemann, 1999).

3 C. Mudde, ‘The Populist Zeitgeist’, Government and Opposition, 39, 4 (2004), p. 543.

4 Ibid., pp. 541–63.

5 E. Laclau, On Populist Reason (London, Verso Books, 2005); J.B. Judis, The Populist Explosion: How the Great Recession Transformed American and European Politics (New York, Columbia Global Reports, 2016); C. Mudde and C.R. Kaltwasser, Populism: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2017); J. Agnew and M. Shin, Mapping Populism: Taking Populism to the People (London, Rowman and Littlefield, 2019); P. Taggart, Populism (Buckingham, Open University Press, 2000).

6 Taggart, Populism, pp. 20–5.

7 Mudde, ‘The Populist Zeitgeist’; Laclau, On Populist Reason; C.R. Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, P. Ochoa Espejo and P. Ostiguy, The Oxford Handbook of Populism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017).

8 D. Johnson, Dreaming of Freedom in South Africa (Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press, 2020).

9 L. Switzer, Power and Resistance in an African Society: The Ciskei Xhosa and the Making of Modern South Africa (Madison, University of Wisconsin Press, 1993); L. Wotshela, Capricious Patronage and Captive Land: A Socio-Political History of Resettlement and Change in South Africa’s Eastern Cape, 1960–2005 (Pretoria, UNISA Press, 2018).

10 G. Mbeki, South Africa: The Peasants’ Revolt (Harmondsworth, Penguin, 1964). p. 162.

11 K. D. Matanzima, Independence My Way (Pretoria, Foreign Affairs Association, 1976).

12 Judis, The Populist Explosion.

13 See D. Resnick, ‘Populism in Africa’, in Kaltwasser et al., The Oxford Handbook of Populism, pp. 101–20.

14 B. Edgar and L. Msumza (eds), Africa’s Cause Must Triumph: The Collected Writings of A. P. Mda (Cape Town, Best Red, 2018), especially ‘Document 70, Letter to Godfrey Pitje at Fort Hare’; also interview with Livingstone Mqotsi, East London, 20 October 2009. Unless otherwise stated, all interviews in this paper were conducted by Leslie Bank.

15 Edgar and Msumza, Africa’s Cause Must Triumph, pp. 1–10.

16 In addition to secondary sources and media reports, this paper draws extensively on oral histories collected over two decades in the city. In 2000 and 2003, I conducted dozens of oral interviews with former residents of East Bank and West Bank townships on forced removals from the 1950s as part of the research for a series of land restitution claims. Here I worked closely with Landiswa Maqasho and Mxolisi Qamarwana, when we were all attached to the Institute for Social and Economic Research at Rhodes University. My second research engagement with the post-war African politics of East London came between 2010 and 2014, when I worked closely with Ndira Mkuzo on the history of the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) in the region, and especially the conduct of anti-sabotage unit chief and security policeman Donald Card.

17 S. Dubow, ‘Introduction: South Africa’s 1940s’, in S. Dubow and A. Jeeves, South Africa’s 1940s: Worlds of Possibility (Cape Town, Double Storey Books, 2005), pp. 1–19.

18 Nel, ‘Racial Segregation’; Bank, Home Space, Street Styles, pp. 1–50.

19 K.P.T. Tankard, ‘The Development of East London through Four Decades of Municipal Control, 1873–1914’ (PhD thesis, Rhodes University, 1990).

20 Ibid., pp. 90–136.

21 M. Hunter, Reaction to Conquest: The Effects of Contact with Europeans on the Pondo of South Africa (London, Oxford University Press, 1936); L. Bank, ‘City Dreams, Country Magic: Re-reading Monica Hunter’s East London Fieldnotes’, in A. Bank and L. Bank (eds), Inside African Anthropology (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2013) pp. 95–126; W. Beinart and C. Bundy, Hidden Struggles in Rural South Africa: Politics and Popular Movements in the Transkei and Eastern Cape, 1890–1930 (Johannesburg, Ravan Press, 1987).

22 L. Bank and M. Qebeyi, Imonti Modern: Picturing the Life and Times of a South African Location (Cape Town, HSRC Press, 2017), pp. 192–7.

23 D. Johnson, Dreaming of Freedom; H. Bradford, A Taste of Freedom: The ICU in Rural South Africa, 1924–1930 (Johannesburg, Ravan Press, 1987).

24 D. Reader, The Black Man’s Portion: History, Demography and Living Conditions in the Native Locations of East London (Cape Town, Oxford University Press, 1961).

25 D.G. Bettison, ‘A Socio-Economic Study of East London, with Special Reference to the Non-European Peoples’ (Masters’ thesis, Rhodes University, 1951).

26 Daily Dispatch, East London, 15 July 1949.

27 D.G. Bettison, ‘A Socio-Economic Study of East London’; Daily Dispatch, 16 June 1949.

28 Daily Dispatch, 11 March 1949.

29 Interview with Philip Mayer, 12 June 1993.

30 Hunter, Reaction to Conquest; see also Bank, ‘City Dreams’, on her East London fieldwork.

31 My own entry into Duncan Village (formerly East Bank) as a participant observer in the late 1990s was negotiated through the civic association and the ANCYL.

32 Bettison, ‘A Socio-Economic Study of East London’, p. 53.

33 ‘Shebeen queens’ were women who sold liquor illegally from their homes. They were often matriarchs who worked with their daughters in running these businesses. Minkley, Border Dialogues, pp. 150–65; also interview with Pule Twaku, 10 June 2004.

34 Daily Dispatch, 8 September 1949; Interview with Ronnie Meine, 15 June 2004; Interview with Reverend Hopa, July 2003.

35 L. Maqasho, L. Bank and B. Mrawu, ‘East Bank Land Restitution Report’, ISER Working Paper (Grahamstown, Rhodes University, 2002).

36 L. Ntsebeza, ‘Youth in Urban African Townships: 1945–1992: A Case Study of East London Townships’ (MA thesis, University of Natal, 1993); Interview with Malcolm Dyani, 20 September 2011; Interview with Lawrence Tutu, 21 October 2011.

37 Daily Dispatch, 3 March 1950.

38 Daily Dispatch, 14 August 1949.

39 Daily Dispatch, 20 August 1949.

40 Daily Dispatch, 28 August 1949.

41 Daily Dispatch, 14 September 1949.

42 A. Mager, ‘Youth Organisations and the Construction of Masculine Identities in the Ciskei and Transkei, 1945–1960’, Journal of Southern African Studies, 24, 4 (1998), pp. 653–67; P. Mayer and I. Mayer, ‘Report of Research on Self-Organisation of Youth Amongst the Xhosa-speaking Peoples of the Ciskei and Transkei’ (unpublished typescript, Institute of Social and Economic Research, Rhodes University, 1972); S. Redding, Violence in Rural South Africa, 1880–1963 (Madison, University of Wisconsin Press, 2023).

43 Mager, Gender and the Making of a South African Bantustan; Redding, Violence in Rural South Africa.

44 See Bank and Qebeyi, Imonti Modern, pp. 162–72; also Bank, Home Spaces, Street Styles, pp. 35–60.

45 Bank and Qebeyi, Imonti Modern, p. 163.

46 Daily Dispatch, 24 January 1951.

47 C. Glaser, Bo-Tsotsi: The Youth Gangs of Soweto, 1935–1976 (Cape Town, David Philip, 2000).

48 Bank and Qebeyi, Imonti Modern, pp. 200–4.

49 Bank and Qebeyi, Imonti Modern, pp. 104.

50 Interview with Malcolm Dyani, 10 September 2011.

51 Bank and Qebeyi, Imonti Modern, pp. 162–6.

52 M. Breier, Bloody Sunday: The Nun, the Defiance Campaign and South Africa’s Secret Massacre. (Cape Town, Tafelberg, 2021); L. Bank and B. Carton, ‘Forgetting Apartheid: History, Culture and the Body of a Nun’, Africa, 86, 3 (2016), pp. 472–503; A. Mager and G. Minkley, ‘Reaping the Whirlwind: The East London Riots of 1952’, in P. Bonner, P. Delius and D. Posel (eds), Apartheid’s Genesis:1935–1962 (Johannesburg, Ravan Press, 1993).

53 Daily Dispatch, 4 September 1949.

54 Bank and Qebeyi, Imonti Modern, pp. 89–94.

55 Daily Dispatch, 10 March and 17 March 1950.

56 Daily Dispatch, 4 April 1950.

57 Bank and Qebeyi, Imonti Modern, pp. 94–5.

58 Daily Dispatch, 11 April 1950.

59 Daily Dispatch, 4 June 1950.

60 Daily Dispatch, 18 April 1951.

61 Daily Dispatch, 20 April 1951.

62 Ibid.

63 Daily Dispatch, 4 May 1951.

64 Edgar and Msumza, Africa’s Cause Must Triumph, Documents 70 and 74, pp. 241–3, 281–3.

65 D. Massey, Under Protest: The Rise of Student Resistance at the University of Fort Hare. (Pretoria, UNISA Press, 2010), p. 60.

66 Interview with Luyanda ka Mtsumza, 21 June 2014; Interview with Livingston Mqotsi, 4 November 2009.

67 Massey, Under Protest, p. 58.

68 Interview with Luyanda ka Mtsumza, 21 June 2014; Interview with Livingston Mqotsi, 4 November 2009.

69 Edgar and Msumza, Africa’s Cause Must Triumph, Documents 63 and 77, pp. 243–6, 284–9.

70 Edgar and Msumza, Africa’s Cause Must Triumph, p. 283 (emphasis in the original).

71 Ibid., pp. 243–6.

72 Massey, Under Protest, p. 65.

73 Ibid., p. 43.

74 B. Edgar and L. Msumsa (personal communication, 20 February 2019).

75 Massey, Under Protest, p. 45.

76 Beinart and Bundy, Hidden Struggles; L. Ntsebeza, Democracy Compromised: The Chiefs and the Politics of Land in South Africa (Leiden, Brill, 2006).

77 Interview with Malcolm Dyani, 13 September 2011; Interview with Hamilton Keke, 10 September 2011.

78 O. Murphy, ‘Race, Violence and Nation: African Nationalism and Popular Politics in the Eastern Cape, 1948–1970’ (PhD thesis, Oxford University, 2013).

79 Ibid.

80 Interview with Vuyani Mngaza, 14 June 2012.

81 Interview with Malcolm Dyani, 13 September 2011; Interview with Hamilton Keke, 10 September 2011.

82 Ibid.; see also Bank and Qebeyi, Imonti Modern, pp. 27–8.

83 Bank and Qebeyi, Imonti Modern, pp. 30–2.

84 Ibid., pp. 34–5.

85 Ibid., pp. 36–7.

86 Daily Dispatch, 12 June 1952.

87 Ibid.

88 Daily Dispatch, 24 June 1952.

89 Ibid.

90 A.A. Dubb, Community of the Saved: An African Revivalist Church in the East Cape (Johannesburg, Witwatersrand University Press, 1976).

91 Laclau, On Populist Reason; Kaltwasser et al., The Oxford Handbook of Populism.

92 Ibid.

93 Breier, Bloody Sunday; Bank and Carton, ‘Forgetting Apartheid’; Mager and Minkley, ‘Reaping the Whirlwind’.

94 Interview with G.M. Nginza, 1 August 2010; Mager and Minkley, ‘Reaping the Whirlwind’.

95 Bank, Home Spaces, Street Styles, p. 54.

96 Daily Dispatch, 20 April 1951; Interview with G.M. Nginza, 1 August 2010.

97 Bank and Qebeyi, Imonti Modern; Breier, Bloody Sunday.

98 P. Mayer, Townsmen or Tribesmen: Conservatism and the Process of Urbanization in a South African City (Cape Town, Oxford University Press, 1961).

99 J. McFall, Trust Betrayed: The Murder of Sister Mary Aidan (Bloemfontein, Nasionale Boekhandel, 1963).

100 Mager and Minkley, ‘Reaping the Whirlwind’.

101 Mager, Gender and the Making of the Ciskei Bantustan.

102 Ntsebeza, ‘Youth in Urban African Townships’; Bank Home Space, Street Styles.

103 Murphy, ‘Race, Violence and Nation’.

104 Interview with Malcolm Dyani, 13 September 2011; Interview with Hamilton Keke, 10 September 2011.

105 Interview with Malcolm Dynani, 13 September 2011.

106 Interview with G.M. Nginza, 1 August 2010.

107 Ibid.

108 This story sometimes starts with an account of the how George Grey ‘deceived’ Nongqawuse before the cattle killing in the 19th century. See, for example, interview with Mongameli Plaatje, 4 June 2011.

109 Murphy, Race, Violence and Nation; L. Bank, Sobukwe’s Children (unpublished, 2020).

110 Ntsebeza, ‘Youth in Urban African Townships’.

111 Interviews with Monde Mkunqwana, 1 August 2010 and 17 November 2011.