Abstract

Little is known about the drivers and governance strategies of appropriation of urban nature in the global south. We compare urban land-grabbing in the city of Colombo, Sri Lanka, with broader understanding of rural land-grabbing in the developing world. We show that the colonial legacy of appropriation and alteration of urban wetlands in Colombo has attained new heights in the neo-liberal period. This cyclical process has caused acute irreversible damage to the wetland ecosystem and a vast majority of the urban poor, with the marginalised continuing to suffer dispossession and environmental hazard. In recognition of the inherent limitations of ‘uncontrollable’ hybrid ecologies, potent social struggles have emerged to resist the continued appropriation agenda. As this cycle is perpetuated, broader social struggles for democratic urban governance have overtaken the pursuit of narrow political-economic goals and internal policy reform.

1. Introduction

The appropriation of nature for capitalist economic projects and dispossession of the communities dependent on them is a common story in the global south (Peluso Citation1992; Fasseur Citation1992; Peet and Watts Citation2004; Margulis et al. Citation2013). Throughout the colonial, post-colonial and neo-liberal periods, this cycle of appropriation and dispossession has been perpetuated in both rural and urban landscapes. Many scholars of political economy (Mintz Citation1983; Peluso Citation1992; Sivaramakrishnan Citation1999) and political ecology (Peluso and Lund Citation2011) have studied the different dynamics of land appropriation in rural and agrarian contexts. The latest wave of privatisation of rural and agricultural land en masse has also gained global attention under the new critique of ‘land grabbing’ and ‘green grabbing’ (White et al. Citation2012; Fairhead et al. Citation2012). However, detailed study of the appropriation of urban nature remains comparatively sparse.

In the global south, most cities are hybrids of agrarian and industrial, and modern and pre-modern traits (Shaw Citation2007). Therefore, the purposes of the appropriation of nature may vary from simple grabbing of peripheral land for urban expansion, to the control and alteration of certain ecological processes such as flood regulation, in order to serve particular urban development goals. It is inevitable that certain social groups and ecological components are disadvantaged and disturbed in these schemes as the urban environment is appropriated and controlled. However, both social resistance by the dispossessed and the intransigence of the unruly and non-equilibrium urban nature (Pickett et al. Citation2008; Robbins Citation2007) often set limits to such grand schemes. In today’s globalising cities of the south, where governance is influenced by factors far beyond the municipal limits (Marcuse and Kempen Citation2000), the causes and consequences of appropriation of nature need to be carefully understood.

In this contribution we examine how the appropriation of the urban wetlands of Colombo, following the neo-liberal economic policies (from 1978) in Sri Lanka, has brought about drastic ecological transformation, causing devastating social impacts, which can well and truly be understood as a social-ecological disaster (Hettiarachchi et al. Citation2014a). We proceed as follows. First, we outline a number of ways for understanding the appropriation of nature in the global south, drawing on the scholarship on agrarian political economy (Peluso Citation1992), political ecology (Robbins Citation2012), critical studies of neo-liberalism (McCarthy and Prudham Citation2004), land grabbing (White et al. Citation2012) and green grabbing (Fairhead et al. Citation2012). We then analyse the drivers of neo-liberal wetland appropriation, the governance strategies used and the social-ecological consequences. This enables us to ascertain: (1) the nature of wetland appropriation strategies in the neo-liberal period; (2) winners and losers of the process; and (3) the ecological, social and political contradictions which set limits to the process.

We show that Colombo’s state-driven appropriation of urban wetlands, which started in the colonial period to facilitate urban expansion, has continued into the neo-liberal period; this is now driven by the drive to create urban space and amenity and to encourage the highly speculative real estate investments of global finance capital. Ultimately, neoliberal wetland appropriation has disadvantaged the vast majority of the urban poor and marginalised communities in the city, and many aspects of this process closely resemble the dynamics observed in studies of modern land grabbing and green grabbing in rural and agrarian contexts. However, while most rural land-grabbing examples involve long- or medium-term agrarian or industrial investments, and vast tracts of lands, Colombo’s urban wetland grabbing involves very short-term real estate investment and smaller land parcels, accompanied by very rapid and intense ecological change.

The short- and long-term social-environmental outcomes of urban land grabbing are complex and multilayered. And, like land grabbing in rural and agrarian contexts, the success of Colombo’s wetland appropriation and alteration projects are inevitably constrained by the inherent contradictions within the sociol-ecological system: where technocratic planning meets non-equilibrium wetland ecology and narrow private financial interests meet explosive social resistance. The openly political struggles now emerging in the Colombo wetlands ultimately raise the broader question of democratic urban governance in the global south, which cannot be resolved within the realm of environmental policy or formal policy reform alone. We conclude by calling for more grounded studies on how scientific guidance can strengthen such social movements.

2. Understanding the governance of nature appropriation in the urban global south

There are many studies emerging from agrarian political economy focused on mass appropriation of peasant land under colonial rule (Peluso Citation1992; Mintz Citation1983; Sivaramakrishnan Citation1999). In most studies, the aim of appropriation was simply to gain land for agrarian purposes or direct extraction of resources embedded in the land. In some cases, the appropriation was aimed at controlling certain ecological process associated with the land such as water regulation (Shiva Citation2002) or sustaining timber reserves (Agrawal Citation2005). Some of these appropriation legacies have continued in the post-colonial period, driven by both national governments and international finance capital (Ferguson Citation1994; Grossman Citation1998). However, compelled by strong political movements, other post-colonial states have developed polices of agrarian land reform which, at least on the surface, diverge from colonial appropriation (Sorenson Citation1967; Peluso and Lund Citation2011).

In the most recent historical phase of capitalism, characterised by economic globalisation, breakdown of the welfare state and transfer of social and natural wealth from common to private ownership (herein, the neo-liberal period; Heynan et al. Citation2007; McCarthy Citation2004; Swyngedouw Citation2004), the process of appropriation of nature has gained renewed attention, giving rise to a whole new lexicon of terms such as ‘land grabbing’ and ‘green grabbing’ (White et al. Citation2012; Fairhead et al. Citation2012). The rise of land grabbing and green grabbing has seen many of the limited land reforms of the post-colonial period reversed. With the exponential increase of privatisation of public assets and financial systems becoming the centre of redistributive activity (Harvey Citation2005), vast tracts of land and resources are being appropriated ‘through a variety of mechanisms and forms that involve large-scale capital’ (Borras et al. Citation2012). Increasingly, green credentials and new valuations of nature are also used in justification of the appropriation. Although there are many echoes of the past forms of appropriations, the new forms involve ‘new actors, political-economic processes and forms of resistance, constructed through new discursive framings’ (Fairhead et al. Citation2012, 254).

These multiple strands of scholarship do not specifically address the urban question; however, they do supply us with the critical tools to explore the strategies, consequences and limits of the appropriation process of Colombo’s wetlands. In contrast to the agrarian setting of most seminal studies cited above, Colombo is an urban case. Many cities of the global south represent both the complex juxtaposition of urban and rural attributes, and the intricate combination of modern and pre-modern traits (Shaw Citation2007). Colombo is an exemplar of this juxtaposition, where subsistence fishery and ad-hoc cattle rearing exist side by side in adjoining neighbourhoods with modern apartment complexes and commercial centres.

To effectively address the specific question raised by the urban context of the case, we combine new understanding of ‘land grabbing’ and ‘green grabbing’ (White et al. Citation2012; Fairhead et al. Citation2012) with scholarship in urban political ecology (Heynan Citation2014; Robbins Citation2007) and urban environmental justice (Schlosberg Citation2007; Pulido Citation2000), to better understand the strategies and outcomes of appropriation of urban nature in the neo-liberal period in Colombo.

3. Methods

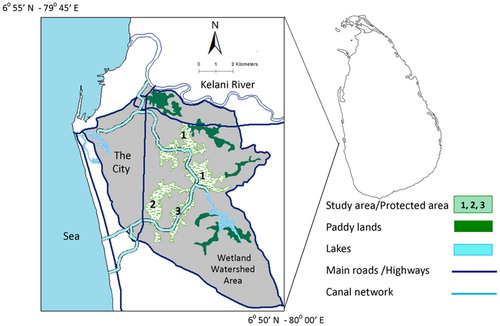

The Colombo metropolitan area (Greater Colombo) is the largest urban agglomerate in Sri Lanka, with a population of 1.3 million. There is a vast network of freshwater marshes, open waterways, estuaries and paddy land scattered across metropolitan Colombo on the flood plain of the Kelani River (). Located at the eastern boundary of the city, the wetlands are 0.3–0.7 metres above mean sea level and become fully inundated during the monsoonal peaks (May–June, September). Today, these wetlands are the main flood retention area for a large part of the urban agglomerate. Most of the wetland (∼1000 hectares) is paddy land owned by private owners. The remaining portion of the wetland (∼500 hectares) is declared a protected area and is state owned.

Figure 1. Map of the study area and its surroundings. The Colombo wetlands are divided into three main segments: 1 – Kolonnawa Marsh, 2 – Heen Marsh, 3 – Kotte Marsh.

These urban wetlands have been under human dominance for more than a millennium including multiple waves of peasant settlers, colonial powers and international investors (Wijetunga Citation2012). Established as a Portuguese trade fort in the sixteenth century, Colombo gained prominence as a colonial city in the region under British rule. During the 1960 and 1970s – the peak decades of post-independence rural–urban migration in South Asia – Colombo’s urbanisation rate reached 6.2 percent. Today, the Urban Development Authority of Sri Lanka projects that the urban population of Sri Lanka will reach 65 percent by 2030.

With the city’s colonial and post-colonial history, political-economic complexity and recent growth trajectory, the Colombo wetlands provides a ‘critical case’ (Flyvbjerg Citation2006) for understanding the appropriation of nature in the urban global south. Furthermore, the case of the Colombo urban wetlands offers a uniquely well-recorded political and ecological history.

We undertook a mixed-methods approach during 2009–2015 including key informant interviews, stakeholder workshops, document analysis, field observation, participant observation, a household survey and a review of the scientific literature. This approach included a comprehensive archival search at the National Archives Department of Sri Lanka, National Library of Sri Lanka and the Colombo Museum Library, and a content analysis of Sri Lanka’s most popular English weekly, The Sunday Times, between 1978 and 2010 to identify important policy and institutional changes, and general socio-economic trends. To identify the broad range of perspectives on governance, 25 key informants were interviewed (using an open-ended format) during the period 2010–2012. Interviewees included officials from the state agencies responsible for environmental management, flood control and urban development; members of local government councils; environmental activists; environmental scientists and engineers; flood control engineers; retired administrators; and community leaders.

We also undertook participant observation at community gatherings, cooperative committee meetings and regular state agency meetings between 2011 and 2013. Three stakeholder workshops were organised in Colombo in October 2009, September 2011 and June 2014 to represent perspectives from the different scales of governance, non-governmental sector, community and academia. Finally, a social survey of 117 households was carried out to investigate flood frequencies and social vulnerability. Ecological data was also obtained from existing sources and field observations.

These data were triangulated to investigate the strategies, consequence and limits of Colombo’s wetland appropriation and alteration at different periods. The analysis was framed according to the theoretical concepts outlined in section 2. The results highlighted different strategies and outcomes according to three discernible historical political-economic periods, colonial, post-colonial and neo-liberal, as will now be discussed.

4. Background to the case

Historical records show that the western coast of Sri Lanka had an advanced civilisation from at least the third century BC (Wijetunga Citation2012) and the freshwater wetlands along the coast were heavily used for paddy cultivation, fishing and navigation (Jayawardena Citation1987). By the 1800s Colombo had become the foremost commercial hub of Sri Lanka under British colonial rule. Colombo also held a vital geo-strategic importance to the British Empire to maintain its dominance in the Indian Ocean (Mills Citation1933). Therefore, transforming Colombo from a colonial fort into a capitalist city has been a major pursuit since at least colonial times.

To attain this goal, protecting the strategically and commercially important inner core of the city from the natural annual floods of the Kelani River was imperative. The need for engineered flood control in Colombo was highlighted by the engineers of the irrigation department from 1889, especially after a devastating flood in 1918. The wetlands were seen as possible space for the city’s expansion and flood infrastructure. The colonial state acquired and reserved large portions of the wetlands (including paddy lands) for flood protection using the authoritarian land acquisition provisions established in the nineteenth century (Crown lands encroachment ordinance – 1840; Waste lands ordinance – 1897). Construction of the head works of the Colombo Flood Protection Plan started in 1930s.

Wetland reclamation and alteration for urban expansion and flood control continued into the period after Sri Lanka’s independence from the British Empire in 1948. During this period the state also introduced some land-reform policies (Paddy Land Act of 1958; Land Reform Act of 1972), where both nationalisation and equitable re-distribution of land entered the policy agenda. Demands for urban housing and public facilities were also raised. Wetland alteration for the flood control head works and reclamation for housing and road construction further altered the wetland ecology and severed the hydraulic connectivity (Hettiarachchi et al. Citation2014b).

From 1978, the Sri Lankan state introduced changes in economic policy which can be widely categorised as neo-liberal policies (Kalegama Citation2004). This included opening the economy as a cheap labour platform, and reversing the limited welfare policies of the post-independence period (Moore Citation1990). The service sector of the economy grew exponentially, giving rise to a new white-collared upper middle class (DPP Citation2002). The growing financialisation of the global economy also brought international capital to Sri Lanka. All of these factors compelled the state to seek the transformation of Colombo into a modern regional commercial hub. The eruption of the civil war (1983–2009) brought thousands (mainly ethnic minorities) from the war-affected areas to ethnic enclaves in Colombo, many within wetlands or in the fringes.

It is within this context that a new round of wetland appropriation and alteration projects were launched in the neo-liberal period, which are different in both scale and character to earlier projects. In the next section, we analyse the political-economic factors and governance strategies that drove neo-liberal wetlands appropriation and the social-ecological outcomes they produced during this modern period.

5. Results and analysis

5.1. Wetlands as a commodity in the neo-liberal ‘free market’

There were a number of political and economic factors that drove neo-liberal wetland appropriations in Colombo. From the early 1980s, blueprints were prepared to expand and modernise Colombo with international funding. New projects for urban expansion and drainage improvement were required (see ). Project proposals underscored the need for ‘slum resettlement’ and potential of ‘better’ utilisation of the marshlands for city expansion (UNDP Citation1978) and called for ‘judicious balance between the demand for land reclamation and drainage’. Developing a new administrative capital in the Sri Jayewardenepura Kotte (eastern suburbs of Colombo) became a priority, and the sites selected for development were predominantly wetland areas. Hence, there was a clear policy drive towards reclaiming wetlands for aggressive city expansion projects at a scale never seen before in Colombo.

Table 1. Institutional and socio-economic reforms impacting on the urban wetlands of Colombo.

The national government’s drive for city modernisation had many economic reverberations in the real estate sector, and local government governance as well. The land value of the areas adjoining wetlands increased by 110 percent between 1990 and 2005 (personal communication, Vijayapala P., former Chief Valuer, Government of Sri Lanka, November 2012). At the same time, national funding for municipal councils nearly halved from 1990 to 2010 (Colombo Municipal Council saw a decrease from 25 to 16.5 percent), compelling the municipalities to seek higher tax earnings through real estate development. From 2005, the real estate sector became a principal mode of internal revenue generation and external capital flows to the Colombo Municipal Council (The World Bank Citation2013).

Real estate in Colombo came to be rigorously marketed in the early 2000s, capitalising on low rents, which averaged around USD 9.00 per square metre per month (in 2011; JLL Citation2016). By 2011 Colombo was ranked by the Asian Development Bank as the ‘most competitive city’ in South Asia (Kyeong Ae and Roberts Citation2011). The early supply of condominium residential units increased from 185 units per annum in 2005 to 1300 per annum in 2012. However, with a low stock of condominium residential units and commercial mall space, the demand for land for real estate development soared (JLL Citation2016; Ariyawansa and Dilhani Citation2009).

The state’s drive to make Colombo attractive for investment and skyrocketing real estate investments and prices had a bearing on the wetlands in number of ways: (1) privately owned wetlands came under pressure to be converted into marketable ‘land’; (2) slums and low-income settlements concentrated around wetlands were targeted to make way for prime real estate; (3) some parts of private wetlands were acquired and altered for improving necessary drainage and road infrastructure; and (4) small remnant patches of wetlands were converted into waterfronts or recreational areas to boost real estate value in their vicinity.

The complex and contradicting roles that the wetlands play in Colombo’s real estate market were summed up in an advertisement by a leading real estate developer as follows:

The rapid development taking place in the current capital of Sri Lanka; Sri Jayewardenepura Kotte bordering Colombo has rejuvenated and combined both cities into a single large wave of city life, with Rajagiriya becoming its new central point. The Rajagiriya area, nestled among a wealth of lush greenery, surrounded by natural wetlands and the picturesque Diyawanna Lake offers the ideal combination where indulgence and luxury go hand in hand. (Fairway Holdings Citation2017)

The state’s drive to clear land directly for real estate ventures increased after the end of the civil war in 2009 (CPA Citation2014). The Metro Colombo Development Project launched in 2010 with World Bank funding, and the Western Province Megapolise Development Project launched in 2016, pursuing foreign direct investment. Both targeted urban renewal, large-scale real estate investments and the improvement of infrastructure (World Bank Citation2013; MoMWD Citation2016). Drainage improvement and eviction of slums remained key components of both schemes: ‘While the removal of unauthorized construction on public land and reservations [mainly wetlands] cannot be avoided, the displaced need to be accommodated in well planned integrated settlements in different parts of the region’ (MoMWD Citation2016, 103).

Hence, while the appropriation and alteration of Colombo’s wetlands had occurred for specific urban purposes since early in the twentieth century, the wetlands in the neo-liberal era became a commodity of the urban real estate market.

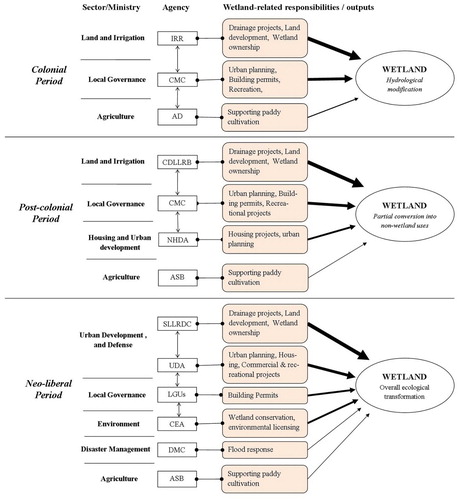

5.2. Governing the appropriation of urban wetlands

Although the impetus for neo-liberal wetland appropriation was driven by the government’s policy to modernise Colombo and by the expanding real estate market, a specific governance framework was required to facilitate it. This required institutional change, organisational restructuring and regulatory changes. illustrates the changing institutional and organisational structures governing the wetlands in Colombo.

Figure 2. The organisational setting and cross-sectoral links of urban wetlands governance in Colombo during the colonial, post-colonial and neo-liberal periods. The thickness of the arrows indicates the magnitude of impact on the wetlands of each agencies’ activities. IRR – Irrigation Department; AD – Agriculture Department; CDLLRB – Colombo District Lowland Reclamation Board; SLLRDC – Sri Lanka Land Reclamation and Development Corporation; UDA – Urban Development Authority; CEA – Central Environmental Authority; CMC – Colombo Municipal Council; DMC – Disaster Management Centre; ASB – Agrarian Services Board.

In 1978, the government established a new state agency– the Urban Development Authority (UDA) – to oversee the fast modernisation of Colombo. The Sri Lanka Land Reclamation and Development Corporation (SLLRDC), which was established in 1968 for the purpose of managing the wetland reclamation projects, was bestowed with an expanded mandate and powers by the amendments to the SLLRDC Act of 1982 and 2006. As a consequence, approximately 500 hectares of private wetlands and paddy lands were acquired by these two organisations under the provisions of the Land Acquisition Act.

The UDA and SLLRDC operated under ministries held by influential ministers in consecutive governments, ensuring strong political clout for their bureaucracies. Both organisations received large budgetary allocations from the government. For example, the budgetary allocations to SLLRDC for capital expenditure increased from 101 million Rupees in 1980 to 2413 million Rupees in 1996. Following the renewed drive for city modernisation after the 2009 end to the Civil War, both the UDA and SLLRDC were brought under the umbrella of the Ministry of Defence to ensure unhindered progress of their projects. Armed forces were directly mobilised to dissipate any resistance against the land acquisition or wetland alteration projects (Gunasekara Citation2010).

However, the period after 1980 (until present) also saw a significant institutionalisation of environmentalism globally (Lane and Morrison Citation2006), which was reflected in Sri Lanka as well. The Central Environmental Authority was established in 1980 under the National Environmental Act (of 1980) and many environmental non-governmental organisations (NGOs; e.g. Environmental Foundation Limited, Young Zoologists Association of Sri Lanka) also emerged. The wetlands received ample attention in this debate, followed by a series of internationally funded wetland studies and the introduction of several wetland protection institutions, including a National Wetland Policy (Hettiarachchi 2015).

These initiatives first compelled state agencies, financiers and consultants to make some reference to the environmental and social significance of the wetlands in development plans (UDA Citation1994). The newer urban development proposals were carefully worded with environmentally sensitive language (The World Bank Citation2013; UDA and MHUD Citation1998). They called for preserving parts of the wetlands as urban bio-diversity refuges and for recreation and eco-tourism purposes. These reports also characterised ‘unauthorised construction’ in poorer areas as a major environmental threat (UDA and MHUD Citation1998; Nippon Koei Co. Citation2002). From 2010 onwards the wetlands became understood as ‘wetland parks’ with the supposed multiple purposes of bio-diversity protection and recreation (Kang Citation2013). Urban development proposals, academic reports and media reports synergistically coalesced around concepts of urban beautification, environmental improvement, slum clearance and the creation of recreational spaces as part of the grand scheme of building a vibrant, modern, international city:

Colombo’s canals have, at last, acquired a new look. The silted, incredibly polluted, stagnating pools of water of yesteryear are no more. The shanties that crowded the banks, making the canals such an eyesore are no longer there. Today what is seen are wide expanses of water that actually flow, neatly constructed banks and boundaries. (Dissanaike Citation1997)

5.3. Social-ecological consequences and social resistance

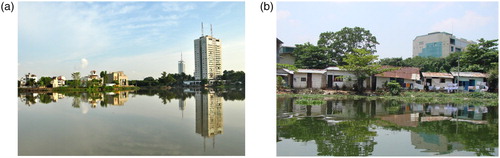

Intense wetland alteration under these projects caused sweeping negative environmental impacts. The hydrological and ecological connectivity of the wetlands was permanently severed. Sustained hydrological modification and nutrient overloading due to watershed urbanisation led to an overall transformation of the wetland type from a marsh to a shrub wetland, with a drastic permanent reduction of the water holding capacity (Hettiarachchi et al. Citation2014b). As a result, moderate to major flood incidents occurred in 1985, 1989, 1990, 1992, 1994, 2002, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008 and 2010, with flood events becoming increasingly severe after 1990. However, the state responded to each cycle of flood intensification with a new cycle of engineering projects that essentially included land acquisition and eviction of low-income communities around the wetland. By the late 1990s, the wetlands were effectively class segregated, where plush waterfront real estate emerged in one part while the conditions of the congested low-income enclaves worsened in the other ().

Figure 3. Income-based spatial segregation in Colombo wetlands. A, ‘Beautified’ wetlands and modern apartment buildings; western end; B, haphazard low-income settlements; northern, eastern end. The two sites are only 1 km apart.

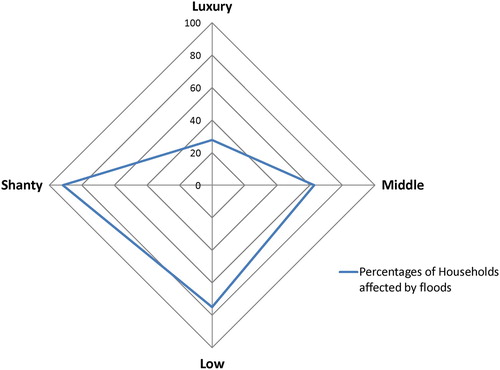

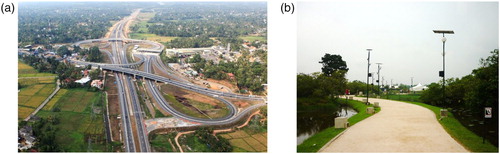

We observed a high prevalence of ethnic minority households in these low-income enclaves, who had fled the civil war in the 1990s. In addition to the routine exposure to floods and diseases (), from the early 2000s these communities had been in constant danger of forcible eviction to make way for ever-expanding real estate projects (CPA Citation2014; Peiris Citation2013; Gunasekara Citation2010). By 2014, about 68,000 residents of Colombo were allegedly under the threat of involuntary relocation (CPA Citation2014; Peiris Citation2013). The same areas from which the so-called ‘unauthorised construction’ was removed were rebuilt with multi-story housing complexes or commercial infrastructure. During the same period large extents of wetlands and paddy land on the immediate outskirts of Colombo were also acquired and reclaimed for transport infrastructure or converted to recreational areas (A and B).

Figure 4. Percentage of households frequently affected by floods as of 2014 according to income level based on house type (n = 177).

Figure 5. A, paddy land and wetlands reclaimed for the outer circular highway in Colombo 2014 (image source: Ministry of Highways, Sri Lanka); B, a new wetland park and recreational area opened in 2012.

There was considerable social resistance at different social levels to the neo-liberal wetland alteration projects. However, the origins and forms of resistance were highly disparate and often disconnected. Acquisitions of private wetlands for the projects were legally challenged with some success by some wealthier owners (e.g. Perera et al. v. Urban Development Authority, et al. – S.C. (F/R) 352/2007). Environmental NGOs also legally challenged wetland alteration projects in Colombo on ecological grounds on several occasions (e.g. Environmental Foundation Limited v. Department of Wildlife Conservation, 2001: C.A. Writ Appln. 1088), which led to the formulation of the National Wetland Policy of Sri Lanka in 2005. A degree of resistance also came from inter-agency rivalry within the state, whereby Central Environmental Authority officials sought public and local government support to outmanoeuvre the development agencies through forming wetland committees and local action groups. However, none of these forms of resistance challenged the primary tenet of wetland appropriation or alteration in Colombo: undermining the people’s right to the wetlands. They all ultimately entered into compromises with the state in some form.

The only form of resistance that challenged the wetland appropriation projects on the basis of the people’s right to environment were the struggles that sparked from the poorer social layers against forced eviction, land acquisition and worsening floods. According to key informants from these communities, and environmental activists, these struggles mainly took the form of spontaneous protests, sit-ins and heckling of government officials and politicians. When the protests turned militant, the police and military used direct suppression, accompanied by protracted coercion and threats, to break grassroots leadership (CPA Citation2014). Opposition political parties often intervened on behalf of the protesters, but such interventions and subsequent legal action failed to stop the projects (Peiris Citation2014). However, within the innumerable permutations and combinations of neo-liberal coalition politics in Sri Lanka, the same opposition parties became accomplices to the state’s authoritarian programmes and the use of force to suppress popular resistance.

6. Discussion

Our analysis shows that the appropriation of Colombo wetlands in the neo-liberal period was driven by the expedited policy of the state to transform Colombo into a modern commercial hub and by the related expansion of the real estate industry. The state facilitated the appropriation with carefully planned governance strategies. We also demonstrate that wetland alteration caused irreversible ecological transformation and largely negative social outcomes. We now contrast the Colombo experience with broader lessons from the scholarship on land-grabbing, green grabbing, urban political ecology and urban environmental justice. We identify the different winners and losers of the process and also analyse the specific ecological, social and political contradictions which set limits to the process in developing cities.

6.1. The anti-democratic nature of wetland appropriation strategies

In the case of urban Colombo, initial colonial wetland appropriation for urban expansion has continued into the neo-liberal period. However, it is now driven by a more virulent drive to create space and amenities for infrastructure and speculative real estate investments, stimulated by the increasing flow of international finance capital since the early 2000s. As Peluso and Lund (Citation2011, 672) state, colonial powers were ‘heavily engaged in land grabbing and creating private property’ which continued beyond de-colonisation. However, what is new in today’s land grabs are the new mechanisms of land control, new justifications and alliances, and the new political economic context of neoliberalism (Peluso and Lund Citation2011).

The state used carefully crafted strategies to privatise and alter large extents of wetland to fit the city modernisation plans that served these private interests, closely tallying with the dynamics generally observed in other neoliberal ‘land-grabbing’ examples (White et al. Citation2012; Margulis et al. Citation2013). Institutional changes introduced to facilitate projects further strengthened bureaucratic state agencies in charge of urban development, enabling them to take a more authoritarian, rather than a democratic, approach in wetland appropriations. Where the projects met with resistance, outright force became the norm. As Levien (Citation2012) demonstrates with regard to rural land grabs for Indian Special Economic Zones, ‘the state acted as a land-broker for capital’, and reversed the limited land-reform policies introduced in the 1960s.

Environmental institutions also expanded in Sri Lanka during the neo-liberal period. However, as many studies on neo-liberal nature (Heynen et al. Citation2007; McCarthy and Prudham Citation2004) have shown, in an economic policy environment dominated by privatisation and deregulation, the efficacy of these institutions is challenged in many ways (also see Morrison Citation2017). As observed in ‘green grabbing’ studies (Fairhead et al. Citation2012), in Colombo an ‘environmental’ pretext for wetlands was used to justify further appropriation of wetlands and eviction of low-income communities.

6.2. Winners and losers

In Colombo’s case, real estate developers, banks, finance houses, urban development agencies, international monetary organisations and the urban upper-middle class identified immediate benefits to the neo-liberal project in converting wetlands into a mosaic of real estate, parks and canals, while a vast majority of the poorer urban population continued to suffer dispossession and environmental hazard.

Government agencies and city administration fulfilled short-term goals, such as flood control or gaining space for urban expansion, through these projects. Local or foreign capital seeking short-term returns in speculative real estate ventures, whose interests were expressed through state agencies and public policy, also attained their profit objectives. Thus, neo-liberal appropriation opened the wetlands for direct private investment. As the urban ecologist Dhrubajyoti Ghosh states, in the view of real estate and commercial investors, urban wetlands is ‘real-estate in the waiting’ (Sarkar Citation2016). If converted into built-up areas, wetlands offer huge prospects for speculative real estate investment. If converted into ‘recreational spaces’ wetlands boost the value of adjoining real estate.

However, the environmental and social ills of wetland appropriation and alteration in Colombo have disproportionately burdened the poor and marginalised segments of the society. The traditional wetland owners, whose land was acquired, were the first victims of appropriation. With the expansion of the real estate market, the poorer working-class communities living in the periphery were evicted to make way for prime real estate and related amenities. As opposition grew against appropriation, direct force and terror were employed by the state to suppress it. The poorest segments were also the immediate and worst victims of wetland ecological transformation and increased floods. As highlighted by environmental justice scholars elsewhere (Schlosberg Citation2007; Pulido Citation2000; Cutter Citation1995), the benefits of ecological functions and the costs of environmental degradation have been redistributed in a way that burdens the poor, through both public policy and market dynamics.

However, regardless of these immediate winners and losers, our analysis shows that appropriation and alteration of the wetlands to make them amenable to narrow capitalist political or economic needs was not successful in the long run. Thus, the process which produced immediate winners and losers in the short term also gave rise to long-term internal contradictions and instability of the overall social-ecological system, and made it more untenable to capitalist economic and political needs.

6.3 The failed project to tame the wetlands: the inherent limits

As many political ecologists have argued, authoritarian governance regimes to arbitrarily control eco-social systems will result in more uncontrollable hybrid ecologies – i.e. ecosystems that are in the process of transformation from their historical ecological traits (Hobbs et al. Citation2009; Robbins Citation2001; Zimmerer Citation2000; Scott Citation1998). Simplistic governance strategies inevitably conflict with manifold social-ecological interactions in complex urban systems. As Fairhead et al. (Citation2012, 242) assert with regard to neo-liberal green grabs, the limits to such projects inherently emerge when ‘market logics meets the disturbing turbulence thrown up by an unruly, non-equilibrium nature’, or ‘when the inherent political and social contradictions generate social and political resistance’. The Colombo example amply confirms this observation for the urban case.

First, the authoritarian appropriation and ecological alteration of the wetlands according to narrow political-economic goals conflicted with the rights of broad social groups to land, ecosystems and livelihoods. Second, the oversimplified, technocratic perspective that drove wetland alteration projects conflicted with the complex interrelationships of the wetland’s social-ecological system. On the one hand, an unforeseen hybrid wetlands ecosystem emerged, which was even less amenable to the ‘development’ aspirations of the state, agency bureaucracy and local and global capital. On the other, ever-intensifying social resistance against these projects by victimised sections of society evoked more violent reprisals from the state.

The effects of appropriation were multilayered and dialectic. Alienation and alteration of any given parcel of wetland had far-reaching effects on hydrology, bio-diversity and soil (Hettiarachchi et al. Citation2014b), which in the long run have transformed the wetland ecosystem into a ‘hybrid ecosystem’. The social impacts were also very complex. On the one hand, the livelihood impacts of wetland appropriation went beyond the communities that directly lost land in appropriations. On the other, the disappearance of wetland management practices associated with livelihoods escalated the wetland ecological transformation. Each new project further transformed the wetland ecology, weakened the traditional uses, and created conditions for increased flooding and urban disasters.

However, these failures, instead of organically leading to integrated understanding of the social-ecological relationships in the wetland system, triggered more virulent and authoritarian moves to appropriate, alter and control the wetlands. This confirms that fundamental contradictions between a governance system and a social-ecological system cannot be resolved by reforms from ‘within’, as long as the conditions that led to those contradictions remain unchanged (Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith Citation1999; Schmidt and Morrison Citation2012).

Thus, the resistance to appropriation became openly political in the neo-liberal period and ultimately raised the question of ‘democracy’ – or, as Peet and Watts (Citation2004) assert, the question of ‘ecological democracy’. The political struggles now re-emerging will be decisive in restructuring and democratising the environmental governance system, and rethinking the narrow capitalist goals and institutions that ‘govern the governing’. Intellectually strengthening such social movements and political struggles will therefore be a central task for those who seek urban sustainability and resilience in Colombo and the global south in general.

7. Conclusion

In many respects, the appropriation of Colombo’s urban wetlands closely resembles the dynamics observed in the predominantly rural scholarship on land grabbing. However, while most rural land-grabbing examples involve long- or medium-term agrarian or industrial investments and vast tracts of lands, urban infrastructure and speculative real estate investments with short-term returns have been the primary drivers of appropriation in cities. Individual extents of land appropriated in cities are also smaller, thereby masking the sheer enormity and rapidity of urban socio-ecological change.

We have shown how Colombo’s wetlands – which were traditionally under peasant or common ownership – have been historically acquired for city expansion and flood-control purposes. In the neo-liberal period this process has exponentially intensified with the state’s policy drive to ‘modernise’ the city, and the expansion of the real estate market. Certain state agencies, local and foreign capital, and wealthy and upper middle-class sections of the society have enjoyed the immediate and short-term benefits of these schemes. The vast majority of traditional wetland owners, the poorer working class and marginalised minority groups continue to suffer dispossession and environmental hazard. Strategies of appropriation have also been undemocratic in essence. And, in the face of mounting social-ecological disasters, the state has resorted to strategies of force for further appropriation. We also demonstrate that environmental institutions have had limited success in curbing wetland appropriation, and at times have been used to provide environmental justification for appropriation. This phenomenon has also been observed in the green-grabbing literature. Further, efforts to re-engineer the wetlands have resulted in an uncontrollable hybrid socio-ecological system, which in the long run has actually intensified floods and hampered so-called ‘development’ goals.

In summary, urban land grabbing is continually challenged by two inherent conflicts in the complex urban social-ecological system: (1) technocratic planning against non-linear, non-equilibrium urban social-ecological interactions; and (2) narrow private interests against broader rights of urban communities (land, ecosystem services, and livelihoods). These conflicts are manifested vigorously in the current neo-liberal period, and have been further intensified by global economic crises and global environmental change.

Emerging social movements to protect the rights of communities for land, livelihoods and environment have ultimately raised the question of democratic urban governance in the global south. These broad social movements – rather than narrow political-economic goals or internal policy reform – could hold the potential to encourage more systemic change in urban environmental governance and ensure urban resilience in the global south. We conclude by calling for more empirical understanding of – and guidance for – such movements.

Acknowledgements

TM wishes to thank Cindy Huchery for research assistance. This work was supported by a CSIRO-UQ Integrated Natural Resources Management Research Award.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Tiffany H. Morrison http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5433-037X

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Missaka Hettiarachchi

Dr Missaka Hettiarachchi is an adjunct senior fellow at the University of Queensland, Australia, and a Senior Fellow of the World Wildlife Fund. He also works closely with the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, James Cook University, Australia. Missaka is an environmental engineer by training and holds a PhD in environmental planning from the University of Queensland. His main research interest is in urban environmental governance and planning in South and Southeast Asia. Email: [email protected]

Tiffany H. Morrison

Associate professor Tiffany Morrison is a political geographer and co-leads the People and Ecosystems programme at the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, Australia. Her research focuses on the design and implementation of complex environmental governance regimes. The current focus of her programme is on uncovering hidden levers for improving the design and implementation of polycentric regimes in Australia, Asia and the US. Email: [email protected]

Clive McAlpine

Professor Clive McAlpine is in the School of Earth and Environmental Sciences at The University of Queensland. McAlpine’s research expertise is in landscape fragmentation and its impacts on biodiversity in tropical and sub-tropical forests, wildlife management and modelling, and vegetation mapping and monitoring using remote sensing. Email: [email protected]

References

- Agrawal, A. 2005. Environmentality: technologies of government and the making of subjects. London: Duke University Press.

- Ariyawansa, R. G., and U. G. M. Dilhani. 2009. Office market in Colombo: an empirical analysis. Sri Lankan Journal of Real Estate 4, no. 2010, [URL] http://journals.sjp.ac.lk/index.php/SLJRE/article/view/124/49

- Borras, S., J. Franco, S. Gomez, C. Kay, and M. Spoor. 2012. Land grabbing in Latin America and the Caribbean. Journal of Peasant Studies 39, no. 3&4: 845–872.

- CPA (Centre for Policy Alternatives). 2014. Forced eviction in Colombo: ugly price of beautification. Colombo: Centre for Policy Alternatives.

- Cutter, S. 1995. Race, class, and environmental justice. Progress in Human Geography 19: 111–18. doi: 10.1177/030913259501900111

- Dissanaike, T. 1997. Colombo’s canals coming to life. Sunday Times, August 31. http://www.sundaytimes.lk/970831/plus8.html#7LABEL1 (accessed November 29, 2014)

- DPP (Department of Physical Planning). 2002. National physical planning policy of Sri Lanka. Colombo: Department of Physical Planning.

- Fairhead, J., M. Leach, and I. Scoones. 2012. Green grabbing: a new appropriation of nature? The Journal of Peasant Studies 39: 237–261. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2012.671770

- Fairway Holdings (Pvt) Ltd. 2017. Serenity – Tranquility surrounds you. Water smoothes you. Infinity captivates you. Fairway Holdings (Pvt) Ltd. http://fairwayholdings.com/RealEstate.

- Fasseur, C. 1992. The politics of colonial exploitation: Java, the Dutch, and the cultivation system. Trans. and ed. R. E. Elson and A. Kraal. R. E. Elson. Ithaca: Cornell University Southeast Asia Program.

- Ferguson, J. 1994. The anti-politics machine: development, depoliticization and bureaucratic power in Lesotho. Minneapolis, MN, USA: University of Minnesota Press.

- Flyvbjerg, B. 2006. Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry. 12: 219–245.

- Grossman, L. S. 1998. The political ecology of bananas: contract farming, peasants and agrarian change in the easter Caribbean. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Gunasekara, T. 2010. The development war—a ‘humanitarian operation’ against Colombo’s poor. The Sunday Leader, May 12.

- Harvey, D. 2005. A brief history of neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hettiarachchi, M., A. Alwis, S. Wijekoon, and K. Athukorale. 2014a. Urban wetlands and disaster resilience of Colombo, Sri Lanka. International Journal of Disaster Resilience in the Built Environment 5: 79–90. doi: 10.1108/IJDRBE-11-2011-0042

- Hettiarachchi, M., T. H. Morrison, D. Wickramasinghe, R. Mapa, A. P. de Alwis, and C. McAlpine. 2014b. The eco-social transformation of urban wetlands: a case study of Colombo, Sri Lanka. Landscape and Urban Planning 132: 55–68. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.08.006

- Heynan, N. 2014. Urban political ecology I: the urban century. Progress in Human Geography 38: 598–604. doi: 10.1177/0309132513500443

- Heynan, N., J. McCarthy, S. Prudham, and P. Robbins. 2007. Introduction. In Neoliberal environments: false promises and unnatural consequences, ed. N. Heynen, J. McCarthy, S. Prudham, and P. Robbins, 1–23. New York, NY, USA: Routledge.

- Hobbs, R. J., E. Higgs, and J. A. Harris. 2009. Novel ecosystems: implications for conservation and restoration. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 24, no. 11: 599–605. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2009.05.012.

- Jayawardena, K. A. 1987. Kotte yugaya. Colombo, Sri Lanka: Samayawardhana Press.

- JLL (Jones Lang LaSalle). 2016. Real estate in Sri Lanka: prospects and potential. Colombo, Sri Laka: JLL.

- Kalegama, S. 2004. Introduction. In Economic policy in Sri Lanka, ed. S. Kalegama, 15–36. New Delhi: Sage.

- Kang, A. 2013. Colombo gains park, loses wetland. Down to Earth, Centre for Science and Environment, http://www.downtoearth.org.in (accessed September 26, 2013)

- Kyeong Ae, C., and B. H. Roberts. 2011. Competitive cities in the 21st century: cluster-based local economic development. Manila: Asian Development Bank.

- Lane, M. B., and T. H. Morrison. 2006. Public interest or private agenda?: a meditation on the role of NGOs in environmental policy and management. Journal of Rural Studies 22: 232–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2005.11.009

- Levien, M. 2012. The land question: special economic zones and the political economy of dispossession in India. Journal of Peasant Studies 39, no. 3&4: 933–969.

- Marcuse, P., and R. V. Kempen. 2000. Conclusion: a changed spatial order. In Globalizing cities: a new spatial order?, ed. P. Marcuse, and R. V. Kempen, 249–275. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publications.

- Margulis, M. E., N. McKeon, and S. M. Jr. Borras. 2013. Land grabbing and global governance: critical perspectives. Globalizations 10, no. 1: 1–23. doi:10.1080/14747731.2013.764151.

- McCarthy, J. 2004. Privatizing conditions of production: trade agreements as neoliberal environmental governance. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 35: 327–41.

- McCarthy, J., and S. Prudham. 2004. Neoliberal nature and the nature of neoliberalism. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 35: 275–83.

- Mills, L. A. 1933. Ceylon under British rule. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mintz, S. 1983. Sweetness and power: the place of sugar in modern history. New York: Penguin Books.

- MoMWD (Ministry of Megapolis and Western Development). 2016. The megapolis: western region masterplan – 2030. Colombo: MoMWD.

- Moore, M. 1990. Economic liberalization versus political pluralism in Sri Lanka?. Modern Asian Studies 24: 341–383. doi: 10.1017/S0026749X00010350

- Morrison, T. H. 2017. Evolving polycentric governance of the great barrier reef. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, doi:10.1073/pnas.1620830114.

- Nippon Koei Co. 2002. The study on storm water drainage plan for the Colombo metropolitan region in the democratic socialist republic of Sri Lanka. Colombo, Sri Lanka: Sri Lanka Land Reclamation and Development Corporation, JAICA.

- Nippon Koei Co., A.W. Atkins Int. and R.D.C. Ltd. 1992. Greater Colombo flood control and drainage improvement project: review report. Colombo, Sri Lanka: Research and Development Consultants (Pvt.) Ltd.

- Peet, R., and M. Watts. 2004. Liberation ecologies. London, UK: Routledge.

- Peiris, V. 2013. Sri Lankan Government Continues Evictions of Colombo’s Poor, http://www.wsws.org (accessed August15, 2013)

- Peiris, V. 2014. Rajapaksha regime demolishes 150 houses in Vanath Mulla with the aid of JVP, http://www.wsws.org/sinhala/2014/2014oct/slud-01o.html (article in Sinhalese)

- Peluso, N. L. 1992. Rich forests, poor people: resource control and resistance in Java. Berkeley, CA, USA: University of California Press.

- Peluso, N. L., and C. Lund. 2011. New frontiers of land control: introduction. Journal of Peasant Studies 38: 667–681. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2011.607692

- Pickett, S. T. A., M. L. Cadenasso, J. M. Grove, P. M. Groffman, L. E. Band, C. G. Boone, W. R. Jr. Burch, et al. 2008. Beyond urban legends: an emerging framework of urban ecology, as illustrated by the Baltimore ecosystem study. BioScience 58: 139–50. doi: 10.1641/B580208

- Pulido, L. 2000. Rethinking environmental racism: white privilege and urban development in southern California. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 90: 12–40. doi: 10.1111/0004-5608.00182

- Robbins, P. 2001. Tracking invasive land covers in India, or why our landscapes have never been modern. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 91, no. 4: 637–659. doi:10.1111/0004-5608.00263.

- Robbins, P. 2007. Lawn people: how grasses, weeds and chemicals makes us who we are. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Robbins, P. 2012. Political ecology. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Sabatier, P., and H. C. Jenkins-Smith. 1999. The advocacy coalition framework: an assessment. In Theories of the policy process, ed. P. Sabatier, 117–166. Boulder, Co: Westview Press.

- Sarkar, R. 2016. Greed, apathy destroying east Kolkata wetlands. thethirdpole.net [URL] http://www.thethirdpole.net/2016/04/06/greed-apathy-destroying-east-kolkata-wetlands/

- Schlosberg, D. 2007. Defining environmental justice: theories, movements, and nature. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schmidt, P., and T. H. Morrison. 2012. Watershed management in an urban setting: process, scale and administration. Land Use Policy 29: 45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2011.05.003

- Scott, J. C. 1998. Seeing like a state. New Haven, CT, USA: Yale University Press.

- Shaw, A. 2007. Introduction. In Indian cities in transition, ed. A. Shaw, xxiii–1. Chennai, India: Orient Longman.

- Shiva, V. 2002. Water wars: privatization, pollution, and profit. Cambridge, MA: South End Press.

- Sivaramakrishnan, K. 1999. Modern forests: statemaking and environmental change in colonial eastern India. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

- Sorenson, M. P. K. 1967. Land reform in the kikuyu country: a study in government policy. Nairobi: Oxford University Press.

- Swyngedouw, E. 2004. Social power and the urbanization of water: flows of power. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- The World Bank. 2013. Colombo, the heartbeat of Sri Lanka. The World Bank, http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2013 (accessed October 4, 2013)

- UDA (Urban Development Authority). 1994. Environmental management strategy for Colombo urban area. Colombo: Urban Development Authority.

- UDA and MHUD (Urban Development Authority and Ministry of Housing and Urban Development). 1998. Colombo metropolitan regional structure plan. Colombo: Urban Development Authority.

- UNDP (United Nations Development Program). 1978. Colombo master plan project. Colombo: Ministry of Local Government & Housing and Construction, Department of Town & Country planning.

- White, B., S. M. Jr. Borras, R. Hall, I. Scoones, and W. Wolford. 2012. The new enclosures: critical perspectives on corporate land deals. The Journal of Peasant Studies 39, no. 3-4: 619–647. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2012.691879

- Wijetunga, W. M. K. 2012. Sri lankeya ithihasaya. Colombo, Sri Lanka: M. D. Gunasena and Co.

- Zimmerer, K. S. 2000. The reworking of conservation geographies: non-equilibrium landscapes and nature-society hybrids. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 90: 356–369. doi: 10.1111/0004-5608.00199