ABSTRACT

Contrary to modernist assumptions, millenarianism has not died out but continues to influence the politics of many marginalised groups in upland Southeast Asia, including the Hmong. This article summarises and analyses post-World War II Hmong millenarian activity in Vietnam, focusing on three case studies from the 1980s onwards, within the political backdrop of ongoing government suspicions of ethnic separatism and foreign interference. Far from being isolated or peripheral, Hmong millenarian rumours and movements interact with overseas diasporas, human rights agencies and international religious networks to influence state responses, sometimes in unexpected ways.

Police forces destroy a funeral house belonging to the Dương Văn Mình sect (reprinted with permission from VETO! Human Rights Defenders Network - http://veto-network.org/featured/the-25-year-persecution-of-the-hmongs-duong-van-minh-religion.html).

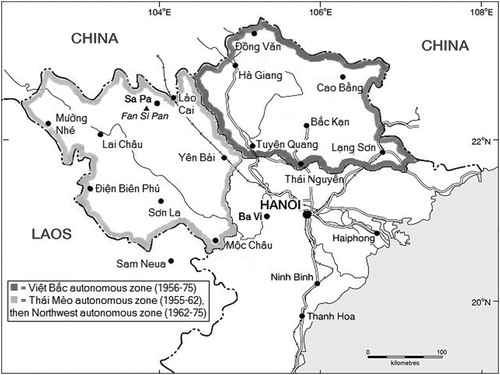

In May 2011, several thousand Hmong assembled at a village in Mường Nhé, a remote district of upland Northwest Vietnam bordering Laos and China (see ). Attracting the attention of major international news websites including BBC (Citation2011a) and Reuters (Ruwitch Citation2011), the gathering was described by contradicting reports as mass protests, a religious event and/or attempts to establish an independent kingdom. This incident lasted just a few weeks before crowds were forcibly dispersed by combined army and police forces (with reports of lethal clashes), however it has had seemingly disproportionate impacts on Vietnam’s ethnic politics and government agendas, as well as human rights discourses and transnational migration. Although small-scale land protests and ‘rightful resistance’ against Vietnamese state actors are more common than often assumed (Kerkvliet Citation2014), rallies which are not organised by the government and manage to mobilise thousands are rare.

While the ‘re-enchantment’ of post-socialist Vietnam has been acknowledged for some time now (Taylor Citation2007), its political implications are yet to be fully explored. With some exceptions, Southeast Asian religious politics usually focuses on either the role of religions in nation building (Chong Citation2010), the harnessing of religion in capitalist expansion (Rudnyckyj Citation2010) or perennial ethno-religious conflict in borderlands regions (Liow Citation2016). Religion may be conceptualised as primordial, constructivist or instrumentalist, with both culturalist and modernisation paradigms having a tendency to essentialise religion and culture (Hamayotsu Citation2008). Alternatively, there has been some engagement with the process of ‘religionization’ in Southeast Asia as Western constructs of religion are appropriated and merged onto disparate local practices, often bringing about a politicisation of religion (Picard Citation2017). A nuanced report of how transnational and state actors interact with – and struggle to categorise or control – heterodox Hmong millenarian activity in Vietnam can aid our awareness of the political agency of marginalised groups in agrarian societies (Kerkvliet Citation2009).

Upland Southeast Asia and southern China have witnessed heterodox religio-political movements which strived to radically transform society over the past two hundred years at least. Hmong historiography indicates the importance of millenarianism in political mobilisation and social transformation, from uprisings in Guizhou and colonial Indochina to mass heterodox Christian conversions in southwest China and Laos (Cheung Citation1996; Gunn Citation1986; Jenks Citation1994; Lee Citation2015; Tapp Citation1989). While early-twentieth century millenarian movements in Vietnam’s lowlands have largely died out or become institutionalised (Tai Citation1983), millenarianism continues to manifest in rural highlands, contrary to predictions about its demise with modernity (Rumsby, Citationforthcoming). There is some fascinating research on recent millenarian activity in Laos, Thailand and the United States (Baird Citation2013b; Hickman Citation2018), but less is available about the Hmong population in Vietnam. This is partly due to official restrictions for non-nationals studying ‘politically sensitive’ issues in Vietnam (Turner Citation2013), whilst national academics and state officials often fall into the trap of uncritically replicating lowland ethnic majority prejudices (Koh Citation2004) – with some notable exceptions (c.f. Ngô Citation2016).

This article addresses a gap in the literature by combining existing English- and Vietnamese-language literature with fresh fieldwork conducted in Vietnam’s highlands. Firstly, we consider the relevance of existing analytical lenses with which to view millenarianism, also noting the recurring significance of rumours as a tool for mobilising resistance against dominant narratives. After a historical contextualisation of Vietnam’s northern highlands, three related cases of recent Hmong millenarianism will be described: the Vàng Chứ (Protestant) movements, the Dương Văn Mình sect, and the 2011 Mường Nhé affair. Among other cultural idiosyncrasies, it will be argued that the multifarious perceptions and interpretations of causes and consequences are not only inherent features of millenarianism, but are also crucial to understanding its enduring political efficacy.

Analytical lenses

Within existing literature, relative deprivation theory holds that the primary reason for millenarian activity is a communal feeling of injustice or disparity within one group in comparison to another group or to a previous, sometimes mythical, time in the group’s past: ‘Communities that feel themselves oppressed anticipate the emergence of a hero who will restore their prestige’ (Chinnery and Haddon Citation1917, 445). For example, Michael Adas argues that the huge socio-economic changes imposed on non-Western societies by colonialism disrupted and threatened established social norms and hierarchies:

significant numbers of individuals and whole groups among the colonized came to feel that a gap existed between what the felt they deserved in terms of status and material rewards and what they possessed or had the capacity to attain (Adas Citation1987, 44).

More than sheer oppression or grinding poverty, it is the consciousness of perceived deprivation which provides a platform for prophets or revolutionaries to predict a radical transformation of society. Adas’ modernist focus on the fundamental changes wrought by colonialism portrays millenarianism as essentially an indigenous reaction to Western civilisation, although millenarian activity in Southeast Asia actually pre-dates and outlasted colonialism. Nevertheless, relative deprivation is obviously still a relevant concept, given the position of Hmong communities at the bottom of Vietnam’s ethnic hierarchy (Ngô Citation2009).

The above lens does not, however, explain why some severe relative deprivation does not lead to significant resistance, or why some societies develop millenarianism while others form different types of social movement. Instead, some anthropologists prefer revitalisation theory, which introduces stress as an additional variable: ‘The essence of revitalization lies in the need of a society under excessive stress to reinforce itself or die’ (Corlin Citation2000, 105). Viewed through this lens, millenarian activity is a response not primarily to perceived deprivation, but to a perceived threat of elimination in some sense – perhaps military defeat, a looming famine or economic crisis, or the loss of cultural values or traditional worldviews. Revitalisation movements are ‘not unusual phenomena but rather recurrent features in human history’ (Wallace Citation1956, 267); its leaders attempt to reformulate cultural patterns, communicate their message and reorganise society to fit the new times.

For example, Corlin highlights an important creation story shared among many groups across upland Southeast Asia about the origins of present inequality between dominant lowland groups and marginalised highlanders, which arose after a universal flood (Corlin Citation1995). For these otherwise disparate groups, the millenarian myth becomes the ‘logical supplement’ to creation myths by seeking to restore an original, primordial balance between different ethnic groups (Corlin Citation2000, 116). Tapp’s extensive research of the Hmong also fits into this analytical lens, as he attributes extensive messianic activity to a unique interaction between invading ideologies (particularly Christianity) and more ‘indigenous’ myths and constructions of history which lead them to expect a messiah (Tapp Citation1989).

A third analytical lens to view Southeast Asian millenarianism is through James Scott’s The Art of Not Being Governed (Citation2009), which argues that time groups like the Hmong have adapted their cultural sensibilities, social structure and religious activity to maintain their autonomy and evade assimilation attempts from lowland state oppression. With messianic charisma acting as a temporary glue to mobilise otherwise dispersed groups, Scott sees millenarianism as a dramatic last resort for upland peoples to ward off state power if less confrontational strategies have failed. Although their expressed aims are never fully realised,

such movements have created new social groups, reshuffled and amalgamated ethnicities, assisted the founding of new villages and new states, provoked radical shifts in sustenance routines and customs, set off long-distance moves, and, not trivially, kept alive a reservoir of hope for a life of dignity, peace, and plenty in the teeth of very long odds (Scott Citation2009, 322).

Mai Na Lee views millenarian rebellion as ‘more of a means of negotiating with the state to loosen its policies, not necessarily an attempt to escape its control’ (Lee Citation2015, 35). Despite also critiquing Scott, Mai Na Lee’s more nuanced framework nevertheless overlaps with this analytical lens of autonomy vis-à-vis the state. She conceptualises Hmong social history in cycles between the secular political broker and the prophet or messianic leader; when the state becomes too oppressive, the Hmong reject the political broker and engage in millenarian rebellion, before eventually being defeated. Nevertheless, the state is forced to reassess over-exploitation and loosen its grip, giving the Hmong more bargaining power. ‘Submission to the state is almost always temporary’, however, as subsequent ‘extraction, corruption, and onerous demands combined with the state’s ambition to impose cultural and linguistic assimilation inevitably lead once again to a volcanic eruption of revolt’ (Citation2015, 35).

Rumours and millenarianism

In earlier work, Scott locates rumours in between the ‘public transcript’ of official/dominant discourse and the ‘hidden transcript’ of subordinates’ true feelings; this intermediate realm hosts ‘politics of disguise and anonymity that takes place in public view but is designed to have double meaning or to shield the anonymity of the actors’ (Scott Citation1990, 19). Exploring ‘superstitious’ rumours during the famine of China’s Great Leap Forward, 1961–65, Smith points out how rumours can be particularly ‘threatening to a regime that aspired to control the ways in which social and political reality was represented’ (Smith Citation2006, 425). Firstly, they are dynamic: the ‘Chinese whispers’ effect means they can suddenly gain new, perhaps political, implications as details are passed on, amended or added to. Secondly, rumours are ‘democratic’, transmitted horizontally between communicator and audience, unlike vertically transmitted official discourse. Thirdly, they are ‘irresponsible’ in the sense that the rumour’s origin is unknown and can easily be denied by individuals should they be called to account by authorities.

Given that rumours are ‘one of the quotidian ways in which deep-seated anxieties … [are] expressed during a period of social and economic upheaval’ (Young, Pinkerton, and Dodds Citation2014, 62), the above features also make them inherently fitting for millenarian communication and mobilisation. Their dynamism allows for the urgent message of imminent salvation to be quickly and democratically dispersed and updated, by groups who are marginalised from dominant narratives but can use rumours to bypass them. Furthermore, their irresponsibility offer the hope for continued millenarian hope after the apparent failure of specific prophecies (Burridge Citation1971), as their sources can be disclaimed while new predictions emerge.

Highlands history

While early historiography of Hmong religio-political activity is often framed through problematic imperialist narratives (either Western or Han Chinese), this has in turn been critically analysed by historians and complemented by work based on Hmong oral histories. Vietnamese academics also have more freedom from self-censorship when writing about history than current affairs, although some nationalist reframing of Hmong millenarian movements as ‘patriotic’ resistance against colonialism is still present (c.f. Vương Citation2005a).

Hmong speakers first migrated to upland Vietnam in the mid-nineteenth century, in search of new agriculture land or fleeing from social upheavals in the aftermath of widespread rebellions in Southern China (Michaud Citation2000). With the wet-rice land already inhabited by other groups including the Thái (Tai), Tày, Nùng and Khmu, most Hmong newcomers settled further uphill, steeper land and practiced shifting cultivation as well as growing opium (Lentz Citation2011, 84). In Hà Giang, on the other hand, Hmong immigrants were more numerous and some carved out more desirable territory by force, with strongmen wielding their own armies – and in turn exploiting other neighbouring ethnic groups. The extent to which these self-declared ‘kings’ tapped into millenarian appeal varied, with Xiong Tai (1860–96) being attributed with miraculous powers such as being able to sow beans which sprouted into armies (Lunet de Lajonquiere Citation1906, 299). No such reports are associated with the Vương kings of Đồng Văn, who colluded with French colonial rule in the early twentieth century and then tactically switched sides to the Viet Minh (Lee Citation2015, 254), their descendants being rewarded with government positions to this day.

However, the majority of Hmong found themselves in marginalised areas, often exploited or oppressed by strongmen from other ethnic minorities in collaboration with the French regime. This triggered more Hmong millenarian uprisings, the two most disruptive led by Xiong Mi Chang (1910–12) and Pa Chay Vue (1918–21), which have been thoroughly analysed by Mai Na Lee (Citation2015) via French colonial archives. Vietnamese-language sources mention other Hmong movements in a similar time period, such as one Giàng Sìa Lừ from Lai Châu province, who was ‘proclaimed king’ [xưng vua] in order to oppose the French (Vương Citation2005a, 123). Vương Duy Quang, a descendant of the aforementioned Vương kings, notes the ‘irresponsibility’ of such messianic prophets who deflected the ultimate source of rumours away from themselves:

The one claiming or proclaiming ‘a king’ would put themselves in a position of subordination to the king never actually claiming themselves to be the king. They would call themselves sons of the king, or messengers of the king … Rumours held that buffalos, oxen, chickens and pigs could be materialized from rocks and stones. (Vương Citation2005a, 124)

In later decades, the Viet Minh offered a credible option for many, though by no means all, disaffected Hmong communities to rally to. During the decisive battle of Điện Biên Phủ in 1954, during which ethnic minorities are acknowledged to have made a vital contribution to the Viet Minh victory, an aspiring young Hmong leader named Vang Pao led 850 soldiers through the mountains of Sam Neua province (Laos) in a vain attempt to relieve the French garrison, arriving too late in the end (McCoy Citation1972, 50). The significant Hmong faction in Laos who sided with America during the Cold War was a serious cause of concern for Vietnamese communists, who would continue to see the Hmong as a potential fifth column until the present day (Ngô Citation2016, 97).

Soon after seizing power in the North, in 1955–6 the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) established two autonomous zones in the areas where most Hmong lived (see ), but their extent of autonomy is questionable and only lasted 20 years before being disbanded. Lentz describes the turbulence caused by the DRV’s attempts to assert its authority in the Northwest and tax opium, a crucial cash crop for the Hmong. Facing famines and poverty, various groups of disaffected Hmong, Dao (Iu Mien) and Khmu again turned to millenarianism between 1955–58:

A political movement offered a vision of a just king who would appear in response to expressions of popular devotion such as fasting, animal sacrifice, dance, and prayer. Once the supernatural sovereign appeared on earth, prophecies told how he would vanquish enemies and deliver followers from their present miseries, especially taxes and labor service, into wealth, bounty, and happiness. Followers quit work, abandoned their fields, staged protests, built hideouts deep in the forest, and offered cutting critiques of the postcolonial social order. (Lentz Citation2017, 20–21)

Over the twentieth century, Hmong millenarian activity has generally become less overtly violent and confrontational as in Southeast Asia as state military and governance technologies became increasingly powerful and penetrated further up into the highlands (Rumsby, Citationforthcoming). Yet, in more covert forms it remains an attractive option for marginalised Hmong, and is still considered threatening by Vietnamese authorities, as evidenced by more recent movements explored below.

Vàng Chứ and/or Protestant Christianity

By the 1980s government campaigns had resulted in the majority of Vietnam’s Hmong population being sedenterized in ‘semi-socialist’ cooperatives, forced to abandon shifting cultivation and opium production (Ngô Citation2016, 31). However, the economic reforms of Đổi Mới in 1986 resulted in dramatic cuts in subsidies for ethnic minorities, causing another bout of extreme hardship and widespread food shortages. This set the scene for the next major wave of Hmong millenarian movements, known initially as Vàng Chứ in Vietnamese (sometimes Vàng Trứ, or Vang Tsu in Hmong). Lào Cai provincial minister Trần Hữu Sơn narrates:

Hmong people have tended to reject traditional family religious beliefs, as well as ancestor worship, faith in and festivals for household spirits and follow a new faith called ‘Vàng Chứ’ (God of heaven), from the Christian and Protestant outlook … A number of people also stopped production and entered the deep forests to gather and spread religious messages according to the Manilla radio, practising to go to heaven or dig shelters. (H. S. Trần Citation1996, 175)

However, before long rumours began to spread about the imminent return of Vàng Chứ, as early as 1990, and recurring dozens of times in various locations. These messianic predictions persuaded many Hmong to travel long distances for gatherings, stop farming and sometimes sell possessions to pay for certain items or make contributions required for salvation (Ngô Citation2016, 84). Unsurprisingly, this caused serious concerns among government officials who tried to repress all new religious activity, often by heavy-handed means, resulting in widespread religious persecution (c.f. Reimer Citation2011). Vietnamese academics saw the FEBC as a tool of ‘hostile’ or ‘reactionary forces’ and accused them of exploiting ‘low intellectual levels, backward customs and economic hardship to deceive the people and force them to follow Vàng Chứ religion’ (Cao Citation2001, 11) by promising an end to suffering and a new life of total abundance after the Messiah’s return. The FEBC was accused of ‘calling Hmong to abandon Communism and follow Vàng Chứ and reminding them not to trust in authorities’ (Lượng Citation2001, 54) – a claim which the radio broadcasters deny (Ngô Citation2016, 101). Tâm Ngô quotes an ominous phrase banded about by government officials: ‘To follow Vàng Chứ is to follow Vang Pao’ (Ngô Citation2016, 98).

Prominent themes emerging from the millenarian discourses include an immanent end to hardship replaced by prosperity and a redressing of the unequal social balances in the favour of the Hmong. For example, one among several articulations of Vàng Chứ’s message was reported on official news:

Vàng Chứ is a star in the sky. The sun and moon feed Vàng Chứ. Lord Jesus is above all things … the whole world belongs to lord Jesus. Lord Jesus goes to all places to share with the sufferings of the poor. Every wrong, every mistake will be overwritten. Then Jesus will return with the sea, the sky and the earth. That will be the time Jesus returns. Jesus will meet the spirits of everybody in the heavens. Jesus will bring everyone to three feasts … (Lù Citation2011)

Given these heterodox millenarian elements present among this new religious movement, should Vàng Chứ be considered as Christian, Protestant, or something else? Vietnamese websites and articles have confused the matter by wrongly claiming Vàng Chứ means ‘king proclamation’ (xưng vua) (M. Q. Nguyễn Citation2001), when in fact it means ‘Lord above all’ or ‘God of heaven’ in Hmong. Most official literature considers Vàng Chứ to be at best a ‘distortion’ of Christianity and at worst a political movement opposed to the government (Lewis Citation2002, 105), which most Hmong have now abandoned by changing to Protestantism (Lượng Citation2001, 53). Conversely, Reimer portrays Hmong millenarian activity small cults infiltrating the wider Protestant community, and accuses Vietnamese authorities of deliberately conflating Christianity with Vàng Chứ in order to warrant widespread religious repression (Reimer Citation2011, 83). However, his assertion over the involvement of ‘Eastern Lightning’, a Chinese millenarian sect portrayed as a terrorist organisation by authorities, appears unfounded.

During fieldwork from 2013 to 2017 in the Vietnamese highlands, I have conducted in-depth interviews and focus groups with hundreds of Hmong research participants about religious and socio-economic change, in addition to witnessing informal conversations through participant observation. While most of the following interview data came from private and confidential discussions, without the presence of official research assistants, these are nevertheless highly sensitive issues in which any deviation from the Party line can be controversial to air openly. Therefore this valuable information source should be contextualised within the political environment of Vietnam (Turner Citation2013).

Many Hmong Christians who were interviewed had initially believed in Vàng Chứ from FEBC broadcasts with little knowledge of Christian doctrine. Their beliefs and religious practice have certainly become more orthodox over time, with greater exposure to transnational Christian teaching and access to Bibles, but most interviewees did not consider this process to be a change of religion, as the state discourse claims. They also accepted that participants of millenarian activity were indeed Christians, not members of another cult – except for the Dương Văn Mình sect described below. Nevertheless, most Hmong Protestants in Vietnam have never taken part in such activity, and many are anxious to distance themselves from anything overtly political. Having spent decades facing discrimination and repression, most church leaders would rather persuade local authorities about the social ‘benefits’ of Christianity and want nothing to do with ‘reactionary’ activities would could result in further hardship for their communities (Ngô Citation2016, 99).

The Dương Văn Mình sect

One Hmong group which is singled out as distinct, by both the government and the wider Christian community, is the Dương Văn Mình (DVM) sect. As a very politically sensitive topic, there is little information available about DVM apart from official documents and human rights watchdogs, which often make contradicting claims. This movement started in 1989 when Mr Dương Văn Mình, aged 28 at the time, fell into a trance and had a vision from God, after which he declared that he was God’s youngest son and God had sent (or entered) him to instruct mankind for three months (Vu Citation2013, 16). He taught his Hmong community in Tuyên Quang that the time of making offerings to spirits was over and that shamans or elaborate, expensive funerals were no longer needed, possibly inspired by similar messages broadcast by the FEBC. This message also resonated with the government’s own campaign attempting to rid ethnic minorities of ‘backwards customs’, including ‘superstitions’ and ‘wasteful’ ceremonies. A unique feature of the DVM sect is the construction of funeral houses for new ceremonies.

Mình’s message spread quickly across the northern provinces of Tuyên Quang, Cao Bằng, Bắc Kạn and Thái Nguyên but was soon opposed by local authorities; Mình was arrested and imprisoned for five years for allegedly ‘spreading superstition with serious consequence’ and ‘defrauding others’ (Vu Citation2013, 17). After being released, Mình was constantly monitored until he fled and went into hiding. Meanwhile, many Hmong continued to believe in and follow the officially unrecognised DVM sect; a credible current estimate is 10,000 followers, although it is also likely that some communities turned from DVM to Protestant Christianity over time, and perhaps vice versa (Vương Citation2007, 11). The sect only gained wider publicity in 2013 after hundreds of Hmong came down to Hanoi to protest against the destruction of their funeral houses by army and police forces, and to demand that the ailing Mình, who was being denied medical treatment, be allowed to enter hospital for dialysis. Hmong protestors were forcibly dispersed, and their communities continue to face harassment (Vu Citation2013, 17–18).

The only related academic research undertaken I have found is by Vương Duy Quang, who claims that in addition to abolishing spirit worship and reforming funeral practices, Mình also prophesied:

In 2000 the earth and sun will collide into each other and everyone will die, whoever wants to live must pray to the Father of Heaven and follow Mình. Whoever follows Dương Văn Mình will be raised to heaven, there the Hmong will have a nation, will be able to read without studying, be able to work with machinery, have a life of happiness with golden bowls and chopsticks, the young will not age, the old will regain their youth and the dead will rise again … (Vương Citation2005b, 209)

All these claims were denounced by Dương Văn Mình himself in recent interviews with VETO! (a human rights agency) in Hanoi, when Mình was trying to access medical care. In 2014, Mình said he had only been supernaturally inspired for three months in 1989, after which he became a normal human again, and emphasised the ‘rational’ elements of his teaching about making funerals less costly. He also denied that the DVM sect was a ‘religion’ (đạo), nor was it a ‘faith’ (tín ngưỡng) but was just a change in ‘customs’ (phong tục) (J.B Nguyễn Citation2014). Mình’s definitional evasiveness seems to be an attempt to carve out a legitimate social space for his movement, since if DVM is considered a religion then it can be accused of being an illegal, unregistered religion. Vietnam only guarantees its citizens the freedom to worship as per a narrow definition of ‘lawful’ religion, heavily influenced by the ‘world religions’ paradigm (Asad Citation1993) which movements like DVM are ultimately a victim of. Nevertheless, perhaps this strategy has been partly successful, since religious persecution towards DVM has eased somewhat in recent years, with Mình living back in Tuyên Quang at present.Footnote1

Meanwhile, DVM followers interviewed by VETO! denied having ever heard about the alleged year 2000 millenarian prophecy, and asserted that financial contributions had been made voluntarily, not under coercion (Vu Citation2013, 16–17). Conversely, during another interview conducted by Radio France Internationale, a DVM follower from Tuyên Quang quoted Mình’s early teaching that ‘in Heaven are nine dragons, under Earth are seven tigers, who desire that everyone on this earth lives by a humane heart of love for each other, helping one another, to help prevent this world from being overwhelmed by the sea waters’ (Trọng Thanh Citation2014). At the very least this quote shows a divergence from orthodox Christian teaching, and possibly also carries an implicit millenarian warning.

Most Hmong people I interviewed knew very little about the DVM sect, unless they lived nearby to the villages of followers. One research participant from Thái Nguyên considered Mình to be a catalyst for the Hmong to start thinking about ‘spiritual’ things, to abandon their altars and ‘follow modernity’. He said that the DVM sect shares some beliefs with Christians, such as the Biblical creation story, but that followers also see Mình as a powerful saviour from heaven. He also claimed Mình had deceived many people into giving him money to buy ‘magic’ cigarettes, which echoes other Vàng Chứ millenarian activity described by Tam Ngo (2015, 84–5). A Christian from Cao Bằng, whose parents had followed DVM for a few years before changing to Protestantism, claimed that the sect was ‘not a religion of God, but a religion of rebellion’. He also notes that while both DVM and Hmong Christians experienced intense religious persecution, the DVM followers were more confrontational and more likely to retaliate against the authorities.

How can these discrepancies be reconciled? Has Vietnamese government discourse confused DVM with other Vàng Chứ millenarian activity, without bothering to understand the nuances between them? Did DVM followers tone down previous millenarian claims when being interviewed in Hanoi, aware of their precarious situation and keen to frame the conflict in terms of human rights? Or did millenarian rumours spread which may not have originated from Mình but which have added to his aura? This article is unable to fully answer these questions but can act as a point of departure for further academic research, which should be undertaken in a way which gives voice to the followers of DVM, unlike state or orthodox Christian narratives. Nevertheless, striking parallels and interesting comparisons emerge from even this limited information presented. Similar questions are raised in the final case of Mường Nhé, which has been subject to more (though still limited) independent research.

Conflicting reports of Mường Nhé

Perhaps Mường Nhé is only an extreme example of the millenarian activity associated with Vàng Chứ, but it is unique in its scale and amount of attention received from official state-sanctioned news, human rights watchdogs, international news agencies, overseas diasporas, religious networks and other blogs. Tâm Ngô gives a partial account of Mường Nhé based on one interpretation of events, largely based on FEBC sources (Citation2016, 95–101), but she fails to represent other voices and perspectives. With wildly differing claims and scant evidence, the full contestation of discourses reveals how people and events have been portrayed and will be remembered, regardless of what actually happened.

Based on official statistics Mường Nhé is the poorest district in all of Vietnam with 93% of inhabitants living in poverty (World Bank Citation2009), two thirds of whom are Hmong. According to one retrospective news report, district security forces had been trying to combat ‘psychological warfare’ rumours that ‘USA and Vang Pao are about to attack Laos and Vietnam’, in circulation since 2003, in addition to sporadic ‘king proclamation’ and ‘Hmong kingdom’ activity every few years since (Lê Tùng Citation2015). Mường Nhé was also a migration destination for Hmong fleeing religious persecution from other parts of North Vietnam (Hồ Citation2013, 38). Unfortunately, the new Christian arrivals encountered equally hostile local authorities and early 2011 saw several incidents of religious repression, which apparently ‘further inflamed simmering discontent by Hmong Protestants’ (Association of Hmong In Exile Citation2013, 5).

In the first few days of May 2011, the outside world became aware of a large Hmong gathering in Huổi Khon village, Mường Nhé district; estimates varied between 5,000 and 11,000 people (Anonymous Citation2011b; BBC Citation2011a), including many from the Central Highlands. The Center for Public Policy Analysis (CPPA), an anti-communist US diaspora group often accused of exaggerating or falsifying information for propaganda purposes, claimed the gathering was sparked by the beatification of Pope John Paul II on 1st May – inspiring non-violent demonstrations by Catholics, Protestants and Animists for ‘religious freedom, land reform and an end to illegal logging’ by state-owned companies (CPPA Citation2011b). Alternatively, a religious persecution watchdog reported that American preacher Harold Camping, who taught that the world would end on 21st May, ‘gathered a following among the Hmong after Hmong-language materials were distributed’ by radio and text messaging through Hmong diaspora networks (CSW Citation2012). According to Ngô, a Hmong man from Mường Nhé adapted Camping’s message by predicting that on 21st May a Hmong king would appear, instead of Jesus Christ. This new prophet was rumoured to have miraculous powers, and on that day ‘an army would rise up out of the dust on the ground, and the rocks on the hills would become weapons, guns, and armaments to destroy his enemies’ (Ngô Citation2016, 96).

On the other hand, official Vietnamese sources identified a different Hmong man from Lào Cai who was branded the instigator and would-be messiah (Nam Hoàng Citation2014). Police sealed off the district and prevented foreign journalists from entering the area, initially blaming ‘bad elements’ within the Hmong of duping the uneducated, ‘gullible’ people into believing a ‘supernatural force’ would lead them into a ‘promised land’, as well as ‘forcing’ people to demand an independent kingdom (Anonymous Citation2011a). Later, foreign ‘extremist’ forces were being credited with inciting the movement, intent on undermining the Vietnamese state and unconcerned about the welfare of the Hmong people (Long Ngũ Citation2017). One article reported the rumour (in order to discredit it) that all existing property and money would turn into dust upon Vàng Chứ’s imminent arrival, before the Hmong king distributed the new land and money to Hmong families who were present at Mường Nhé (Gia Huy and Ngọc Hà Citation2011). According to the above reports, this recurring theme of redistribution caused many people to sell possessions and donate it to exploitative leaders, gaining nothing but misery in return.

If there is little consensus regarding the triggers of the Mường Nhé incident, the details of proceedings are equally contested. The district authorities claimed to have ‘stabilised’ the region as early as 8th May, while regretting the death of one child due to ‘poor sanitary conditions’ (BBC Citation2011b). According to the district head of police, security forces found 300 tents surrounded by a fence, with stores of provisions, torches, petrol and the like (N. T. Nguyễn Citation2015). The official narrative claims that once the Hmong realised they had been duped and that no king had arrived, most wanted to leave but were trapped in by the ringleaders, until the police saved them (Dan Que Citation2013) – although this story doesn’t add up if the crowds were waiting for 21st May, since police arrived long before then. In stark contrast, diaspora networks claimed that dozens of Hmong were killed by army troops, using attack helicopters and chemical weapons on Hmong who were fleeing into Laos, with thousands of Vietnamese and Laotian security forces combining in a joint operation (Association of Hmong In Exile Citation2013; Blair Citation2011). However, it seems highly unlikely that Vietnam would need or want to rely on Lao troops, whilst similar unfounded rumours about chemical weapons used on Hmong dissidents in Laos are commonly circulated among the US diaspora (Pribbenow Citation2006).

Hmong interviewees asserted that most or all participants at Mường Nhé were Protestants; many travelled in secret on the pretext of attending a relative’s wedding. They attributed the speed of the gathering to Hmong clan structure, gullibility or ‘curiosity’; apparently, many people did not necessarily believe the rumours but came just to see what would happen. Common topics raised were about the Hmong kingdom and the return of God or Jesus to Mường Nhé. Given the prevalence of ‘protest’ on online sources, it is notable that people rarely called the event a protest, and no-one cited religious persecution as a reason contributing to the gathering. A few people mentioned the involvement of former Hmong soldiers from Laos who had fought against the communists in the Cold War, who still had some weapons. No-one knew how many casualties there were, but one interviewee’s brother-in-law had died there.

Interpretations, consequences and rumours

The divergent understandings of Mường Nhé’s causes and proceedings led to multifarious interpretations and consequences, probably quite different to those intended by the millenarian participants. Initially, official news reacted by blaming Christian conversion for luring the Hmong by the ‘false promise’ of ‘material enrichment without labour’ and ‘curing illness without modern medicine’, instead of actually addressing what happened in Mường Nhé (Ngô Citation2016, 126). The Hmong population were depicted as mostly loyal but ignorant citizens, led astray by malign leaders (or foreign troublemakers). According to one interviewee, the Vietnamese state sees the ‘invisible hand’ of the enemy behind all politically subversive activity, especially among borderlands ethnic minorities. In March 2012 eight Hmong men were given 30 months’ imprisonment for ‘public disorder’, four more men in December for ‘plotting to overthrow the government’ (one man received seven years), and one more in August 2013 after fleeing to China and being returned by Chinese authorities (BBC Citation2012, Citation2013). Official sources noted that the culprits were illiterate and confessed their crimes with ‘tears of repentance’ (Chu Citation2012), while international sources considered sentences to be relatively lenient considering the serious crimes they were convicted of.

On another level, events in Mường Nhé acted as a catalyst for state-led development and territorialisation initiatives in the district, as they attempted to prevent anything similar from reoccurring. Subsequent news reports publicised how local authorities were implementing measures such as poverty eradication loans to all poor households, without discriminating against millenarian participants (Nam Hoàng Citation2014); another article highlights the start of adult literacy classes in 2013, to increase people’s ‘awareness’ so that they would not be enticed by false propaganda again (Vũ Toàn Citation2015). A Hmong interviewee verified the government’s response of improving living standards in Mường Nhé, demonstrating that even failed millenarian movements have occasionally resulted in positive outcomes for the Hmong, as happened after the Pa Chay rebellion of 1918–21 (Gunn Citation1986). However, a recent article complains about continued uncontrolled migration after 2011, illegal deforestation as newcomers claim farmland and small protests against local authority restrictions on deforestation, apparently mobilised by Hmong Christians. According to the report, these ongoing disturbances ‘show that Protestant activity is “full of potential” for hostile forces who oppose Vietnam, through the guise of human rights and religious freedom’ (Long Ngũ Citation2017).

While the government clearly did not want any martyrs and denied killing of participants, overseas diaspora groups and human rights groups asserted a conflicting narrative with emotive headlines such as ‘Attack Helicopters Unleashed Death on Hmong’ and ‘Vietnam Forces Kill 72 Hmong, Hundreds Arrested and Flee’ (CPPA Citation2011a, Citation2011b). These websites portrayed the event not as a separatist or religious movement but primarily as reasonable demonstrations against economic or religious discrimination, amplifying the brutality of the government’s response. In January 2012, Vietnamese-American human rights agency Boat People SOS (BPSOS Citation2012) released a report compiled from direct interviews with Hmong witnesses of the Mường Nhé incident, who fled to Bangkok as refugees along with hundreds of other Hmong Christians seeking asylum. The US Hmong diaspora seised this narrative to lobby senators about human rights violations, although Washington’s desire to strengthen ties with Hanoi at the time meant concerns fell largely on deaf ears. Even Vang Pao’s son Neng Chu Vang waded into the debate, asking Vietnamese authorities to ‘go easy’ on arrested Hmong (Đ. Đ. Trần Citation2011). This transnational development supports Salemink’s observation that ‘conflicts in Vietnam’s Central Highlands are changed by their increased framing in human rights terms by or for international human rights institutions’ (Salemink Citation2006, 34).

Unlike US-based diasporas and human rights activists, however, local Christian networks and missionaries strongly criticised the ‘protest’ narrative and denied that the Hmong had called for independence. According to Ngo, this reflects a desire to ‘tame’ or subdue the millenarian threat, having spent so long persuading the Vietnamese government to recognise Hmong Christians (Ngô Citation2016, 101). The FEBC warned listeners not to attend Mường Nhé, and most Christian leaders denounced the gathering as a cult. A Hmong denominational leader told me that Mường Nhé was started by false teachers exploiting Biblical themes such as the Exodus and promised land for separatist motives, accusing participants of then passing on false information to overseas networks that they were just praying and fasting, so that foreigners would not sympathise with how the authorities handled it. Professor of religion James Lewis blamed Vietnam’s ban on printing the Bible in Hmong language, meaning Christians were more easily led into unorthodox political activity (Việt Hà Citation2011).

A striking feature of all three case studies is the power of rumours in attracting both millenarian support and government concern. They were remarkably far-reaching, persuading Hmong from the Central Highlands to travel thousands of miles north to Mường Nhé in 2011. Themes were adapted from Hmong traditions as well as Christian discourse and repeated or rearticulated by different actors, apparently not losing their efficacy despite previous millenarian prophecies not coming to pass. Apocalyptic predictions of a radical upheaval of existing power relations posed a challenge to the Vietnamese state’s legitimacy, with narratives shifting from implicit critiques of social inequality to explicit aspirations for Hmong independence. This is not to deny that rumours were also used to deceive or coerce people, but one effect has nevertheless been ‘to open up spaces of alterity and opposition within the grid of state power … in ways that complicate the dichotomy of domination and resistance’ (Smith Citation2006, 425).

Perhaps for this reason, the Vietnamese state responded to the above movements with severe repression and attempts to discredit them. Web articles and entire books were published in Vietnamese and Hmong language denouncing Vàng Chứ and related rumours (e.g. Vi Hoàng Citation2001), although their impact is questionable given the low levels of Hmong literacy and access to such materials. The ‘irresponsibility’ of rumours is seen when DVM and his followers denied older prophecies attributed to him, but he was unable to escape culpability as they became too strongly associated with his name. Related official texts routinely ridicule and lament Hmong gullibility in believing incredible rumours and being duped by ‘bad elements’ exploiting millenarian fervour. However, this misses the point that the purpose of rumours (at least partially) is to provide ‘the terms and tropes through which people caught up in changing worlds may vex each other, question definitions of value, form alliances and mobilize oppositions’ (Comaroff and Comaroff Citation1993, xxiii). Seen in this light, we can better understand the ‘curiosity’ of many people who travelled to Mường Nhé in 2011 with different aspirations and agendas, without necessarily believing all of the rumours.

Conclusions

By way of closing, it is instructive to apply different analytical lenses of millenarianism to Vàng Chứ activity, the Dương Văn Mình sect, and the Mường Nhé events of 2011. Relative deprivation is certainly relevant to the Hmong, who are keenly aware of their unenviable socio-economic position at the bottom of the ethnic hierarchy in Vietnam – more so than other marginalised minorities (Turner, Derks, and Hạnh Citation2017). Legends of a past Hmong kingdom may have served as a contrast for disgruntled Hmong, but more frequently interviewees compared their situation negatively with the religious freedom and relative prosperity experienced by Hmong in Thailand. Adas (Citation1987, 186) describes how the ‘failure or absence of alternative means of protest’ enhances millenarian appeal; one unsubstantiated theory is that Vang Pao’s death in January 2011 encouraged messianic activity in Mường Nhé as the Hmong gave up any remaining secular political goals.Footnote2

Revitalisation theory sees the trigger of millenarian activity as a perceived threat of social or cultural extinction. The post-Đổi Mới period was extremely traumatic for Hmong communities who lost the economic support of subsidies but still faced the growing pressure of cultural assimilation to the ethnic majority (McElwee Citation2004). The Vàng Chứ and DVM movements represent a radical break from the past in some respects, but they also offered hope for the Hmong to preserve their identity and ethnic distinctiveness – hence why Vàng Chứ millenarian activity often stipulated the wearing of handmade hemp clothes, ‘a mark of authentic Hmong culture’ (Ngô Citation2016, 85). Alternatively, from Tapp’s perspective, recent heterodox millenarianism could also be seen as ‘indigenous’ counter-movements in reaction to the mass Christian conversions.

The third analytical lens of autonomy from the state is somewhat less useful in understanding recent Hmong millenarian activity. While a desire for autonomy clearly contributed to the Mường Nhé gathering, the discourse was not about freedom or ‘anarchy’ but rather about setting up a new state or kingdom. This reflects other critiques of Scott that he ignores the numerous historical state-making projects by highlanders themselves in the Southeast Asian Massif (Michaud Citation2017, 7). Mai Na Lee’s conceptualisation of millenarianism as negotiation with the state is more relevant, as the DVM sect and Vàng Chứ activity have attempted to carve out autonomous social space.

Given the dynamic and religious nature of Hmong millenarianism combined with its occurrence in remote areas and the marginal status of participants, the extraordinary diversity of rumours and interpretations should not be surprising. As with Salemink’s (Citation2003) analysis of the colonial ‘Python God’ millenarian movement in Vietnam’s Central Highlands, varying accounts of millenarian activity have been used and construed by different actors to promote their own agendas. Indeed, this uncertainty and ambivalence is arguably key to millenarianism’s continued potency; although the movements never achieve their ultimate goals of salvation and redemption, they can cause other, unexpected effects. In the case of Vietnam, Hmong millenarian activity has stimulated international debates on human rights and religious freedom, triggered temporary and permanent migration, and stimulated new state development initiatives.

Although the article has dealt with Vàng Chứ, Dương Văn Mình and Mường Nhé separately, the extent to which they are distinct movements is debatable (further research on DVM sect could shed more light on this). Burridge noted that millenarian movements tend to outlive the apparent failure of their prophecies, since ‘the failure to gain the millennium is in itself, given the ambience, a guarantee that the activities will occur again or continue in more muted form’ (Citation1971, 73). Nor is this likely to be the final time we here about Hmong millenarianism in Vietnam’s highlands. The present lack of political space in Vietnamese society, which illegalises almost all forms of social discontent, forces those in desperate situations to consider more radical measures.

Acknowledgements

This article has benefited from feedback and advice of Juanita Elias, Jeff Wasserstrom and the two anonymous journal reviewers whose feedback greatly assisted in the development of this piece of work. I am, of course, most grateful to the Hmong research informants, who must also remain anonymous. For ethical reasons the underlying data which this article is based on is highly confidential and cannot be made openly available. For further information please contact the author ([email protected])

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ORCID

Seb Rumsby http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8190-4874

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Seb Rumsby

Seb Rumsby is a PhD Candidate at the University of Warwick’s department for Politics and International Studies, having been awarded a scholarship from the Economic and Social Research Council. He speaks fluent Vietnamese and has published several short articles, newspaper articles and book reviews on the politics of ethnicity and religion in Southeast Asia to date. Seb has a related book chapter on ‘Historical Continuities and Changes in the Ethnic Politics of Hmong Millenarianism’ forthcoming. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 Personal communication with VETO! Human Rights Defenders’ Network (August 2017).

2 Email exchange with Dr Robert Cooper (May 2014).

References

- NB: in-text quotes of Vietnamese-language sources are the author’s translations

- Adas, Michael. 1987. Prophets of Rebellion: Millenarian Protest Movements Against the European Colonial Order. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Anh Tuấn. 2014. “Ai Được Lợi Từ ‘Nhà Đòn’? [Who Benefits from the ‘Funeral Houses’?].” Tuyên Quang Online, News. 2014. http://baotuyenquang.com.vn/phap-luat/an-ninh-trat-tu/ai-duoc-loi-tu-nha-don-37945.html.

- Anonymous. 2011a. “Tin Đồn Nhảm gây Mất an Ninh Huyện Mường Nhé [False Rumours Cause Loss of Security in Muong Nhe District].” Tuổi Trẻ Online. 2011. http://tuoitre.vn/tin/chinh-tri-xa-hoi/20110505/tin-don-nham-gay-mat-an-ninh-huyen-muong-nhe/436660.html.

- Anonymous. 2011b. “Vietnam Paints Hmong Cult Meeting as Christian.” Compass Direct News. 2011. http://www.charismamag.com/site-archives/570-news/featured-news/13497-vietnam-paints-hmong-cult-meeting-as-christian.

- Anonymous. 2013. “Sự Thực về Dương Văn Mình và Cái Gọi Là ‘Tín Ngưỡng Dương Văn Mình’ [The Truth about Duong Van Minh and the so-Called ‘Duong Van Minh Religion’].” Vì Tổ Quốc Việt Nam. 2013. https://vitoquocvietnam.wordpress.com/2013/10/23/su-thuc-ve-duong-van-minh-va-cai-goi-la-tin-nguong-duong-van-minh/.

- Asad, Talal. 1993. Genealogies of Religion: Discipline and Reasons of Power in Christianity and Islam. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Association of Hmong in Exile. 2013. “Submission to the Universal Periodic Review of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.” Democratic Voice of Vietnam. 2013. http://dvov.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/hmong-in-exile-joint-upr-submission-vietnam-january-2014.pdf.

- Baird, Ian G. 2013a. “Millenarian Movements in Southern Laos and North Eastern Siam (Thailand) at the Turn of the Twentieth Century Reconsidering the Involvement of the Champassak Royal House.” South East Asia Research 21 (2): 257–279. doi:10.5367/sear.2013.0147.

- Baird, Ian G. 2013b. “The Monks and the Hmong: The Special Relationship between the Chao Fa and the Tham Krabok Buddhist Temple in Saraburi Province, Thailand.” In Violent Buddhism – Buddhism and Militarism in Asia in the Twentieth Century, edited by V. Tikhonov and T. Brekke, 120–151. London: Routledge.

- BBC. 2011a. “Vietnam: Ethnic Hmong ‘in Mass Protest in Dien Bien.’” BBC News. 2011. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-pacific-13284122.

- BBC. 2011b. “Vụ Mường Nhé: Có Trẻ Em ‘Ốm Chết’? [The Muong Nhe Affair: Did a Child ‘Get Sick and Die’?].” BBC Vietnamese-Language Service. 2011. www.bbc.com/vietnamese/vietnam/2011/05/110508_hmong_death.shtml.

- BBC. 2012. “Vietnam Jails Hmong Men for Plot after ‘messiah’ Rally.” BBC News. 2012. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-20701830.

- BBC. 2013. “Án Tù Cho Người H’Mông và Khmer [Prison Sentences for Hmong and Khmer People].” BBC Vietnamese-Language Service. 2013. http://www.bbc.co.uk/vietnamese/vietnam/2013/09/130926_hmong_khmer_verdict.shtml.

- Blair, Philip. 2011. “Bloodshed Crackdown against Hmong Christians in Dien Bien.” VietCatholic News. 2011. http://vietcatholic.net/News/Html/89754.htm.

- BPSOS. 2012. “Persecution of Hmong Christians and the Muong Nhe Incident.” Boat People SOS. 2012. https://www.scribd.com/document/142076984/The-Muong-Nhe-Incident-02-12-12.

- Burridge, K. 1971. New Heaven New Earth: A Study of Millenarian Activities. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Cao, Nguyên. 2001. Sự Du Nhập và Ảnh Hưởng Của Đạo Tin Lành Trong Đồng Bào dân Tộc H’mông ở Một Số Tỉnh Miền Núi Phía Bắc Nước Ta Hiện Này Để Nghiên Cứu [The Introduction and Influences of Protestant Christianity among the Hmong in the Northern Mountainous Provinces]. Hanoi: Hanoi University of Social Sciences.

- Cheung, S. 1996. “Millenarianism, Christian Movements, and Ethnic Change among the Miao in Southwest China.” In Cultural Encounters on China’s Ethnic Frontiers, edited by Stevan Harrell, 217–247. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Chinnery, E.W.P., and A.C. Haddon. 1917. “Five New Religious Cults in British New Guinea.” Hibbert Journal 15: 448–463.

- Chong, Terence. 2010. “Religion and Politics in Southeast Asia.” Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia 25 (1): vii–viii. doi: 10.1355/SJ25-0A

- Chu, Quốc Hùng. 2012. “Xét Xử Sơ Thẩm vụ ‘Phá Rối an Ninh’ Tại Mường Nhé [Judgment for ‘Disturbing Public Order’ in Muong Nhe].” Vietnam Plus. 2012. https://www.vietnamplus.vn/xet-xu-so-tham-vu-pha-roi-an-ninh-tai-muong-nhe/133632.vnp.

- Comaroff, John L., and Jean Comaroff. 1993. Modernity and Its Malcontents: Ritual and Power in Postcolonial Africa. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Corlin, C. 1995. Common Roots and Present Inequality: Ethnic Myths among Highland Populations of Mainland Southeast Asia. Copenhagen: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies.

- Corlin, C. 2000. “The Politics of Cosmology: An Introduction to Millenarianism and Ethnicity among Highland Minorities of Northern Thailand.” In Civility and Savagery: Social Identity in Tai States, edited by Andrew Turton, 104–121. Surrey: Curzon.

- CPPA. 2011a. “Vietnam, Laos: Attack Helicopters Unleashed Death on Hmong.” Nam Viet News. 2011. https://namvietnews.wordpress.com/2011/05/22/vietnam-laos-attack-helicopters-unleashed-death-on-hmong/.

- CPPA. 2011b. “Vietnam Forces Kill 72 Hmong, Hundreds Arrested and Flee.” Online PR News. 2011. https://www.onlineprnews.com/news/139559-1305659370-vietnam-forces-kill-72-hmong-hundreds-arrested-and-flee.html.

- CSW. 2012. “Vietnam 8 Hmong Sentenced.” Christian Solidarity Worldwide. 2012. http://www.csw.org.uk/2012/03/16/press/1332/article.htm.

- Dan Que. 2013. “Secrets of Unfamiliar Region on Grim Hill.” Saigon Online. 2013.

- Gia Huy, and Ngọc Hà. 2011. “Chuyện Hoang Đường ở Bản Huổi Khon [The Unbelievable Story of Huoi Khon Village].” Dien Bien Province Office for Culture, Sports and Tourism. 2011. http://svhttdldienbien.gov.vn/Article/1545/Chuyen-hoang-duong-o-ban-Huoi-Khon.html.

- Gunn, Geoffrey C. 1986. “Shamans and Rebels : The Batchai (Meo) Rebellion of Northern Laos and North-West Vietnam (1918–21).” Journal of the Siam Society 74: 107–121.

- Hamayotsu, Kikue. 2008. “Beyond Doctrine and Dogma: Religion and Politics in Southeast Asia.” In Southeast Asia in Political Science: Theory, Region, and Qualitative Analysis, edited by Erik Kuhonta, Dan Slater, and Tuong Vu. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Hickman, Jacob. 2018. “The Making of a Hmong Millennium: Economies of Recognition in a Diasporic Religious Community.” In Preparation.

- Hồ, Xuân Định. 2013. “Thực Hiện Chính Sách Của Nhà Nước Việt Nam Đối Với Tin Lành ở Các Tỉnh Miền Núi Phía Bắc Hiện Nay [Implementing the Vietnamese State’s Policies with Regards to Protestantism in the Northern Mountainous Regions at Present].” Religious Research 12 (126): 31–43.

- J.B Nguyễn, Hữu Vinh. 2014. “Gặp Dương Văn Mình: Tội Nhân Hay Bệnh Nhân Bị Từ Chối Cứu Chữa Giữa Thủ Đô? [Meeting Duong Van Minh: Criminal or Patient Being Refused Treatment in the Capital?].” Radio Free Asia Vietnam. 2014. http://www.rfavietnam.com/node/1947.

- Jenks, R. D. 1994. Insurgency and Social Disorder in Guizhou: The “Miao” Rebellion, 1854–1873. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- Jonsson, Hjorleifur. 2010. “Above and Beyond: Zomia and the Ethnographic Challenge of/for Regional History.” History and Anthropology 21 (2): 191–212. doi:10.1080/02757201003793705.

- Kerkvliet, Benedict J. 2009. “Everyday Politics in Peasant Societies (and Ours).” The Journal of Peasant Studies 36 (1): 227–243. doi:10.1080/03066150902820487.

- Kerkvliet, Benedict J. 2014. “Protests Over Land in Vietnam: Rightful Resistance and More.” Journal of Vietnamese Studies 9 (3): 19–54. doi: 10.1525/vs.2014.9.3.19

- Koh, Priscilla. 2004. “Persistent Ambiguities: Vietnamese Ethnology in the Doi Moi Period (1986 -2001).” Journal of the Southeast Asian Studies Student Association 5: 1–21.

- Lê Tùng. 2015. “Để Mường Nhé Bình Yên [Leave Muong Nhe in Peace].” Petro Times, News. 2015. http://petrotimes.vn/de-muong-nhe-binh-yen-304641.html.

- Lee, Mai Na M. 2015. Dreams of the Hmong Kingdom: The Quest for Legitimation in French Indochina, 1850–1960. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Lentz, Christian C. 2011. “Making the Northwest Vietnamese.” Journal of Vietnamese Studies 6 (2): 68–105. doi:10.1525/vs.2011.6.2.68.

- Lentz, Christian C. 2017. “Cultivating Subjects: Opium and Rule in Post-War Vietnam.” Modern Asian Studies 51 (4): 1–40. doi: 10.1017/S0026749X15000402

- Lewis, James. 2002. “The Evangelical Religious Movement Among the Hmong of Northern Vietnam and the Government’s Responce.” Crossroads: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 16 (2): 79–112.

- Liow, J. 2016. Religion and Nationalism in Southeast Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Long Ngũ. 2017. “Cảnh Báo Xung Đột Văn Hóa ở Vùng Đồng Bào dân Tộc Thiểu Số Theo Đạo Tin Lành [Warning of Culture Clash into the Ethnic Minority Regions Who Follow Protestantism].” Biên Phòng. 2017. http://www.baomoi.com/canh-bao-xung-dot-van-hoa-o-vung-dong-bao-dan-toc-thieu-so-theo-dao-tin-lanh/r/23084810.epi.

- Lù, Pò Khương. 2011. “Đạo Vàng Chứ” và Những Hệ Lụy … Buồn [‘Vang Chu Religion’ and Resultant … Sorrows].” Biên Phòng. 2011. http://btgcp.gov.vn/Plus.aspx/vi/News/38/0/255/0/1663/_Dao_Vang_Chu_va_nhung_he_luy_buon.

- Lunet de Lajonquiere, E. 1906. Ethnographie Du Tonkin Septentrionale (Rédigé Sur l’Ordre de M. P. Beau, Gouverneur Général de l’Indo-Chine Française, d’après Les Études Des Administrateurs Civils et Militaire Des Provinces Septentrionales). Hanoi: E. Leroux.

- Lượng, Thị Thoa. 2001. “Quá Trình Du Nhập Đạo Tin Lành-Vàng Chứ Vào dân Tộc H’mông Trong Những Năm Gần đây [The Process of Protestant-Vang Chu Integration into the Ethnic Hmong in Recent Years].” Nghiên Cứu Lịch Sứ [Historical Research] 315 (2): 49–57.

- McCoy, Alfred W. 1972. “Flowers of Evil: The CIA and the Heroin Trade.” Harpers Magazine CCXLV (1466): 47–53.

- McElwee, P. 2004. “Becoming Socialist or Becoming Kinh? Government Policies for Ethnic Minorities in the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam.” In Civilizing the Margins: Southeast Asian Government Policies for the Development of Minorities, edited by C. R. Duncan. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press.

- Michaud, Jean. 2000. “The Montagnards and the State in Northern Vietnam from 1802 to 1975: A Historical Overview.” Ethnohistory 47 (2): 333–368. doi:10.1215/00141801-47-2-333.

- Michaud, Jean. 2017. “What’s (Written) History for? On James C. Scott’s Zomia, Especially Chapter 6½.” Anthropology Today 33 (1): 6–10. doi: 10.1111/1467-8322.12322

- Nam Hoàng. 2014. “Yên Bình ở Huổi Khon [Peace at Huoi Khon].” Công Lý. 2014. http://congly.vn/phong-su/yen-binh-o-huoi-khon-51095.html.

- Ngô, Tâm T. T. 2009. “The ‘Short-Waved’ Faith: Christian Broadcasting and Protestant Conversion of the Hmong in Vietnam.” MMG Working Paper 09-11.

- Ngô, Tâm T. T. 2016. The New Way: Hmong Protestantism in Vietnam. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Ngô Trần. 2013. “Đừng Để Thù Nghịch Lấp Đầy Lý Trí [Don’t Let Resentment Overwhelm Reason].” An Ninh Thủ Đô. 2013. http://anninhthudo.vn/thoi-su/dung-de-thu-nghich-lap-day-ly-tri/522690.antd.

- Nguyễn, Minh Quang. 2001. Religious Problems in Vietnam: Questions and Answers. Hanoi: World Publishing House.

- Nguyễn, Ngọc Trường. 2015. “Sự Thật Đằng Sau ‘Vương Quốc Mông’ Taik Mường Nhé [The Truth behind the ‘Hmong Kingdom’ in Muong Nhe].” Dien Bien Phu Online. 2015. http://baodienbienphu.info.vn/tin-tuc/phap-luat/131991/su-that-dang-sau-“vuong-quoc-mong”-tai-muong-nhe.

- Picard, Michel. 2017. The Appropriation of Religion in Southeast Asia and Beyond. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pribbenow, Merle L. 2006. “‘Yellow Rain’: Lessons from an Earlier WMD Controversy.” International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence 19 (4): 737–745. doi: 10.1080/08850600600656525

- Reimer, Reg. 2011. Vietnam’s Christians. Pasadena: William Carey Library.

- Rudnyckyj, Daromir. 2010. Spiritual Economies: Islam, Globalization and the Afterlife of Development. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Rumsby, Seb. forthcoming. “Historical Continuities and Changes in the Ethnic Politics of Hmong Millenarianism.” In Memories, Networks and Identities of Transnational Hmong, edited by Ian G. Baird. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Ruwitch, John. 2011. “Thousands of Hmong Stage Rare Vietnam Protest.” Reuters. 2011. http://uk.reuters.com/article/2011/05/06/uk-vietnam-hmong-protest-idUKTRE7450Q120110506.

- Salemink, Oscar. 2003. The Ethnography of Vietnam’s Central Highlanders: A Historical Contextualization, 1850–1990. London: Routledge Curzon.

- Salemink, Oscar. 2006. “Changing Rights and Wrongs: The Transnational Construction of Indigenous and Human Rights among Vietnam’s Central Highlanders.” Focaal – European Journal of Anthropology 47: 32–47. doi:10.3167/092012906780646514.

- Scott, James C. 1990. Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Scott, James C. 2009. The Art of Not Being Boverned: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Smith, S. A. 2006. “Talking Toads and Chinless Ghosts: The Politics of ‘Superstitious’ Rumors in the People’s Republic of China, 1961–1965.” The American Historical Review 111 (2): 405–427. doi: 10.1086/ahr.111.2.405

- Tai, Hue-Tam Ho. 1983. Millenarianism and Peasant Politics in Vietnam. London: Harvard University Press.

- Tapp, Nicholas. 1989. Sovereignty and Rebellion: The White Hmong of Northern Thailand. Bangkok: White Lotus Press.

- Taylor, Philip. 2007. Modernty and Re-Enchantment: Religion in Post-Revolutionary Vietnam. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

- Trần, Hữu Sơn. 1996. Văn Hóa H’Mông [Hmong Culture]. Hanoi: Ethnic Minority Culture Publishing House.

- Trần, Thị Thiệp. 2002. Thực Trạng Tôn Giáo Trong Dân Tộc Mông ở Yên Bái [Religious Situation among the Mong People of Yen Bai]. Yen Bai Provincial Committe Public Relations Department.

- Trần, Đông Đức. 2011. “Con Tướng Vàng Pao Nói về vụ Mường Nhé [General Vang Pao’s Son Speaks about Muong Nhe].” BBC Vietnamese-Language Service. 2011. http://www.bbc.com/vietnamese/vietnam/2011/05/110520_chu_vang_view.

- Trọng Thanh. 2014. “Vụ Xử Người H’Mông Tuyên Quang Có Dấu Hiệu Đàn Áp ‘“tín Ngưỡng”’ [Judgement of Tuyen Quang Hmong Who Show Signs of ‘Religious’ Repression].” Radio France Internationale. 2014. http://vi.rfi.fr/viet-nam/20140319-viet-nam-vu-xu-nguoi-h’mong-tai-tuyen-quang-co-dau-hieu-dan-ap-«-tin-nguong-».

- Tùng Duy. 2014. “Lật Tẩy Kẻ Dùng Tà Đạo Mê Hoặc Người dân Chống Phá Nhà Nước [Unmasking Thouse Who Use Religious Fervor or People to Oppose the State].” Tiền Phong. 2014. http://www.tienphong.vn/xa-hoi/lat-tay-ke-dung-ta-dao-me-hoac-nguoi-dan-chong-pha-nha-nuoc-733137.tpo.

- Turner, Sarah, ed. 2013. Red Stamps and Gold Stars: Fieldwork Dilemmas in Upland Socialist Asia. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- Turner, Sarah, Annuska Derks, and Ngô Thúy Hạnh. 2017. “Flex Crops or Flex Livelihoods? The Story of a Volatile Commodity Chain in Upland Northern Vietnam.” Journal of Peasant Studies. doi:10.1080/03066150.2017.1382477.

- Vi Hoàng. 2001. Đừng Tin Lời Rắn Độc [Don’t Believe the Snake Poison Words]. Hanoi: Ethnic Minority Culture Publishing House.

- Việt Hà. 2011. “Cuộc Biểu Tình Của Người Hmong: Vàng Chứ Là Gì? [The Hmong Protest: What Is Vang Chu?].” Radio Free Asia. 2011. http://www.rfa.org/vietnamese/in_depth/who-is-vang-chu-vh-05132011171704.html.

- Vu, Quoc Dung. 2013. “The 25-Year Persecution of the Hmong’s Duong Van Minh Religion.” VETO! Human Rights Defender Network. http://veto-network.org/veto-content/uploads/2014/12/VN_PersecutionDuongVanMinhReligion-VETO_ReportEN-1.pdf.

- Vũ Toàn. 2015. “‘Huổi Khon Đã Bình Yên, Vui vẻ Rồi’ [“Huoi Khon Is Peaceful and Happy Now”].” Công Luận. 2015. http://congluan.vn/huoi-khon-da-binh-yen-vui-ve-roi/.

- Vương, Duy Quang. 2005a. “Hiện Tượng ‘Xưng Vua’ ở Cộng Đồng Hmông [The ‘King-Making’ Phenomenon in the Hmong Community].” In Người Hmông, edited by Thái Sơn Chu, 121–135. Ho Chi Minh City: Youth Publishing House.

- Vương, Duy Quang. 2005b. Văn Hóa tâm Linh Của Người H’Mông ở Việt Nam: Truyền Thống và Hiện Tại [Spiritual Culture of the Hmong in Vietnam: Traditional and Present]. Hanoi: Culture and Information Publishing House.

- Vương, Duy Quang. 2007. “Sự Cải Đạo Theo Ki Tô Giáo Của Một Bộ Phận Người Hmông ở Việt Nam và Khu Vực Đông Nam Á Từ Cuối Thế Kỷ XIX Đến Nay [Christian Conversion of Some Hmong in Vietnam and Southeast Asia from the End of the 19th Century Until Now].” Ethnology Journal 4: 3–13.

- Wallace, Anthony F. C. 1956. “Revitalization Movements.” American Anthropologist 58 (2): 264–281. doi: 10.1525/aa.1956.58.2.02a00040

- World Bank. 2009. “MapVIETNAM.” The World Bank. 2009. http://www5.worldbank.org/mapvietnam.

- Young, Stephen, Alasdair Pinkerton, and Klaus Dodds. 2014. “The Word on the Street: Rumor, ‘Race’ and the Anticipation of Urban Unrest.” Political Geography 38: 57–67. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2013.11.001