ABSTRACT

This study compares Mexico's rural population and cross-border out-migration trends between 2000 and 2010 censuses. In spite of widespread predictions of post-NAFTA depopulation, the size of Mexico's rural population has remained steady. This study documents the significant absolute size and geographic concentration of Mexico's persistent rural population as well as the decreasing rate of outmigration to the United States. Mexico experienced two contradictory trends between 2000 and 2010: (1) migration intensity increased in one-third of predominantly rural municipalities, while (2) more than half of the rural population continued to live in municipalities with low dependency on cross-border migration.

Introduction

The globalization of Mexico's economy and society, accelerated by NAFTA, was widely expected to lead to rapid rural depopulation. Massive imports of subsidized US grain threatened to wipe out smallholder corn producers and increase migration. The backdrop for this trend, from the point of view of migration studies, is a stereotypical Mexican rural village – mainly inhabited by the elderly, lined with empty houses that have been improved by remittances, and paved with roads that facilitate the holiday returns of families from the United States – as seen in high out-migration states like Zacatecas. Some rural scholars have thus concluded that ‘migration of the peasant population had become one of the factors that most impact and define rural livelihoods’ (e.g. Arias Citation2009, 10). In response, only the Zapatistas have offered sustained, overt resistance to globalization, rooted in their de facto regional autonomy in Chiapas. Other rural social actors, though, have demonstrated bursts of resistance, such as the 2002–2003 ‘The Countryside Won’t Take It Any More’ movement, the farmworkers who conducted a rare 2015 general strike in Baja California, or the region-wide autonomous indigenous cooperatives that challenge displacement caused by extractive industries in the Sierra Norte region of Puebla. Many rural Mexicans have indeed chosen to exit, while others have exercised voice. Yet the primary rural response to economic and social challenges has been neither – though less publicly visible: Mexico’s rural population continues to grow.

These contradictory trends – increased migration combined with rural population growth and pockets of resistance – leads us to flip the widespread assumption about the inexorable spread of communities becoming ever more dependent on migration to the United States. Instead, we ask: How much of the rural population is exercising their ‘right to not migrate?’Footnote1 This phrase, ‘el derecho a no migrar’ in Spanish, was originally coined by Mexican rural development strategist Armando Bartra (Citation2003, 33). He framed it in the context of the 1917 Mexican Constitution’s Article 123, which promised: ‘All persons have the right to socially useful and dignified work; to that end job creation and social organization for work will be promoted … ’

This framing of the question engages with the ‘migration and development’ debate by bridging migration, development, and rights agendas. Yet until President López Obrador was elected in 2018, this innovative framing around not migrating had been taken up by only a few Mexican peasant movement and migrant rights advocates. López Obrador promised alternatives to previously-dominant national economic policies associated with provoking high rates of out-migration, adopting a ‘right to not migrate’ discourse: ‘We want Mexicans to be able to work and be happy where they were born, where their family is, where their customs and culture are; [we want] migration to be a choice, not an obligation’ (Borbolla Citation2019).

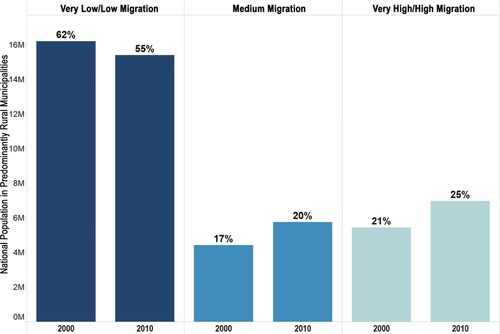

This is the context for this study’s analysis of the Mexican rural population that did not leave to work in the United States. A comparison of out-migration trends between 2000 and 2010 shows the remarkable persistence of Mexicans who chose to remain in the countryside. This study uses a new indicator of rurality based on predominantly rural municipalities and finds that the national population continues to be 25% rural. Of that rural population, 55% lives in rural municipalities that do not depend significantly on cross-border migration.Footnote2 In effect, they are exercising their ‘right to stay home.’Footnote3 This study’s main contribution is empirical, to recognize both the ongoing persistence and the geographic concentration of Mexico’s rural population. This step is necessary but not sufficient to analyze the diverse survival strategies that the rural population pursues while remaining in their localities and regions – an agenda that goes beyond the scope of this study.

Post-NAFTA migration predictions and trends

During the debate over NAFTA, both advocates and critics tended to agree that the trade agreement would negatively affect Mexico’s smallholder grain production while favoring vegetable and fruit production for export.Footnote4 At the time, Mexico’s under-secretary of agriculture, Luis Téllez, predicted that the government’s rural reforms would likely force about half of the rural population to move within a decade or two (Golden Citation1991).Footnote5 The MIT-trained economist assumed that a reduction in agricultural employment would consequently reduce the rural population. Yet this view overlooked several factors that could potentially reduce rural migration: rural Mexicans had already widely diversified their sources of income; they exercised sufficient political clout to claim government subsidies to ostensibly buffer the impact of the trade opening; and a new rural-urban interdependence had emerged that would allow rural communities access to urban employment opportunities (Hoogesteger and Rivara Citation2020; Torres-Mazuera Citation2012). Indeed, at the time, two prominent migration experts predicted that while Mexico’s pro-market rural reforms would increase cross-border migration in the short term, migration would subsequently fall after just a few years (Cornelius and Martin Citation1993, 491–492).

These predictions were largely based on the changing composition of rural household income, as it demonstrated the shifting relative importance of on-farm- and off-farm activities in the local economy. Mexico’s agricultural income and rurality are now delinked due to the hybrid nature of rural spaces that increasingly combine rural geographies amidst semi-urban arenas for income generation (e.g. Fairbairn et al. Citation2014). This condition is referred to as the ‘new rurality,’ offering new reconfigurations of local rural spaces that are not fully dependent on agricultural livelihoods and are more dependent on political competition, internal and international migration dynamics, violent displacement, and the power shift in local governance from agrarian to municipal authorities (Appendini and Torres-Mazuera Citation2008; Gordillo de Anda and Plassot Citation2017; Torres-Mazuera Citation2012, Citation2013).

As it turned out, NAFTA’s impact on migration confirmed the critics’ worst fears – at least in the first decade. Annual rates of cross-border migration more than doubled, from an estimated 295,000 in 1991 to a peak of 725,000 in 2000, as shows. By 2009, however, those annual flows had decreased to an average of 140,000 and have remained mostly flat in the last decade. Between 2010 and 2019, the Mexican-born population in the US declined by 7% (Israel and Batalova Citation2020). While Mexico-US migration patterns in the decade of the 1990s have been well-studied, the subsequent flattening of the trend following this peak has received much less research attention.

Figure 1. Annual immigration from Mexico to the U.S., 1991–2019 (in thousands). Source: Pew Research Center estimates based on 2000 Census, American Community Survey (2000-2018), March Supplement to the Current Population Survey (2000-2019) and monthly Current Population Surveys, January 2000-December 2019. Thanks to Jeffrey Passel for sharing this data.

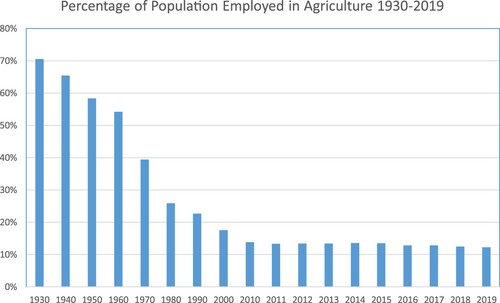

The large exodus was closely tied to a reduction in agricultural employment. Mexico’s agricultural census found that the number of jobs in agriculture dropped 20% between 1991 and 2007. Rural families were hollowed out, as the majority of farm jobs registered in that census as unpaid family labor were lost, possibly reflecting the displacement of the adult children of smallholders. Surveys report that the combined wage/nonwage income from agriculture fell from 38.7% to 17.3% of total rural household income (Scott Citation2010, 76; 82). The peasant economy was in free fall. The agricultural share of overall employment also continued to drop during this period, though not as quickly as in previous decades. Indeed, the fall in agricultural employment is a long-term structural trend, and the decades with the sharpest drops (in both absolute and relative terms) were also the decades of Mexico’s most rapid urbanization and industrialization, long before the trade opening. (See ). Yet since 2000, the pace of this long-term decline appears to have slowed.

Figure 2. Long-term trends in the agricultural share of Mexican employment: 1930-2019. Source: Encuesta Nacional de Ocupación y Empleo. Thanks to Prof. John Scott of CIDE for sharing this data.

Several countertrends also boosted the agricultural sector during the 2000–2010 period. In contrast to all predictions, corn production rose rather than fell after NAFTA, and Mexico reached self-sufficiency in corn for human consumption for the first time in decades (Fox and Haight Citation2010). Broad-based peasant protests had emerged in 2002–2003 under the banner of ‘The Countryside Won’t Take It Any More’ campaign, but they were too late to influence the trade opening, which the Mexican government implemented much more quickly than NAFTA required.Footnote6 But this protest movement did encourage the government to gradually double agricultural spending in real terms over the rest of the decade – though most of that spending ended up being directed to medium and large producers (Fox and Haight Citation2010).Footnote7 The number of ejido properties (community-based landholdings created by the agrarian reform) also increased, despite the 1992 neoliberal reforms to land rights. In 2016, 52% of rural land was still in the agrarian reform sector, including 5.5 million titleholders (Robles Berlanga and Mejia Citation2018, 17–18).

By 2010, net Mexican migration to the United States had fallen to below zero (González-Barrera Citation2015). By 2015, the total Mexican immigrant population in the United States had decreased by 725,000 from its peak of 12.7 million during the 2008 Great Recession (Pew Research Center Citation2017). Note that these estimated annual migration rates are not direct indicators of rural displacement. The rural share of border-crossers dropped to less than half of the total during this period, as shown by a large-scale Mexican university longitudinal survey. By the 2000s, just under half of Mexican border-crossers reported that they had been working in agriculture before leaving.Footnote8

Explanatory factors for this remarkable shift in Mexico-US migration trends include the rise and fall of US labor market demand, the US government’s increased immigration enforcement, as well as Mexico’s ongoing demographic transition towards smaller families in both rural and urban areas (e.g. Passel and Suro Citation2005, 10). More specifically, these factors include lower fertility rates (Sánchez and Pacheco Citation2012), decreased circularity, higher levels of education, dramatic increases in the costs of crossing (Massey Citation2020),Footnote9 higher unemployment paired with slower demographic growth in the border region, the long U.S. economic recession of 2008, and the impacts of organized violence on rural livelihoods. Moreover, tenure insecurity and restrictions on land markets (especially rentals) are still important barriers to migration both internally and internationally, especially in rural areas (de Janvry et al. Citation2013). However, this study will not attempt to disentangle the relative weights of these different factors. Rather, it will focus on documenting the size and distribution of Mexico’s remaining rural population, including the share of those who remain in predominantly rural municipalities that are not significantly dependent on US migration. The focus here is on the 2000–2010 period because of the availability of comprehensive municipal level data on outmigration, which do not exist for earlier periods. When comparably comprehensive data become available for the post-2010 period, trends are likely to reflect continued reductions in out-migration due to a combination of stricter border enforcement, more expensive costs of crossing and a diversification in rural household access to Mexican labor markets.

Migration and development – or development and migration?

This study’s central empirical question about the size and distribution of Mexico’s still-rural population is framed by the complex relationship between migration and development. The links between migration and development may seem straightforward, insofar as persistent underdevelopment clearly encourages migration – both from the countryside to cities and across national borders. Yet it has proven challenging to construct an appropriate analytical framework for understanding that relationship. One reason is that the study of migration and the study of rural development have evolved on parallel tracks that rarely intersect.

Conceptual frameworks for studying rural development tend to consider migration and migration decisions as exogenous. For example, diverse studies of the peasant economy often do not take into account migration for wage labor (especially by non-family heads), in spite of widespread recognition of semi-proletarianization (family survival strategies that combine wage labor with sub-subsistence farming for household consumption). Decisions about rural livelihoods or whether to engage in collective action to claim rights are rarely studied alongside decision-making about whether to move to the city. As for migration studies, they tend to address decisions about whether or how to migrate without addressing prospects for sustainable rural livelihoods or collective action to fight for alternatives to migration. Indeed, consider how rarely rural development journals include studies of migration, and how rarely migration studies journals include studies of rural development.Footnote10 The result is two sets of analytical frameworks that each study different dimensions – of the same rural families – who, in practice, are continuously assessing the pros and cons of exit versus voice.Footnote11 In other words, these two approaches often study the same people (peasants and farmworkers, for example) yet pose totally different questions, make different assumptions, and adopt different research methods.

This disconnect sets the stage for the subtle-yet-significant difference between the framing concept of ‘migration and development’ and that of ‘development and migration.’ The ‘migration and development’ frame, the subject of numerous global conferences, focuses primarily on the impacts of remittances (social as well as financial) on ‘sending’ countries and communities (Rother Citation2012). This frame has been adopted by numerous studies of the consequences of remittances for sending countries and communities, as well as in debates about the potential of these resources to leverage local development in rural areas (Aparicio and Meseguer Citation2012; Bada Citation2014, Citation2016; Çağlar Citation2006; Glick-Schiller and Faist Citation2010; Portes Citation2009). The implicit assumption of ‘migration and development’ is that migration and large-scale exits are a given. In that framework, the key question then becomes how to improve or mitigate the effects of such migration on home countries and communities (e.g. Castles Citation2009; De Haas Citation2005; De la Garza Citation2013; Fajnzylber and López Citation2007; Mora Rivera and López Feldman Citation2010). In contrast, the ‘development and migration’ frame focuses on how national development paths and policies influence migration decisions and patterns. In this view, governments that pursue low-wage economic strategies, or decline to invest in sustainable rural development, actively encourage migration (Delgado Wise and Covarrubias Citation2009; García Zamora Citation2005; García Zamora, Olvera, and Pérez Veyna Citation2018). To sum up the key differences, the ‘migration and development’ frame addresses the effects of migration on development, while ‘development and migration’ addresses the effects of development strategies on migration.

These contrasting analytical frames are associated with very different sets of research questions and government policies. The dominant focus of ‘migration and development’ is on migration policy, at least in the Americas. This term includes policies that directly affect migrants either during or after their departure – but not before they migrate, at which point they are choosing between voice and exit. Migration policy analysts look at government programs that attempt to encourage collective remittances in community development for local public goods; channel individual remittances into productive, job-creating investment rather than consumption; or defend migrants’ rights abroad and their right to a safe return (e.g. Alarcón Citation2002; Duquette-Rury Citation2019; García Zamora Citation2005; Goldring Citation2002; Hall Citation2011; Orozco and Lapointe Citation2004; Orozco and Scaife Díaz Citation2011). By contrast, the ‘development and migration’ frame addresses national development policies through the lens of their impact on employment (Delgado Wise and Veltmeyer Citation2016): for example, whether and how agricultural policy priorities bolster or undermine on-farm employment (Fox and Haight Citation2010). These contrasting approaches also tend to differ in terms of their level of analysis, at least in the Mexican case. While both are informed by the transnational context, the study of migration and development tends to have a micro-focus on family or community-level social and economic decision-making, while the study of development and migration tends to be national, sectoral, or regional in focus.

Parallel to these different analytical perspectives and policy strategies for addressing the relationship between migration and development are various public interest advocacy agendas, at least in the Mexico-US context. In the migration policy frame, the advocacy focus is on how policies can more directly respond to migrant interests, such as preventing abuse and corruption in transit; regularizing status; and providing official support for people-to-people philanthropic efforts involving collective remittances, mainly focused on local public goods. In the development policy frame, though, the public interest advocacy focus is on addressing the underlying causes of migration, with an emphasis on policies that encourage sustainable job creation – and, increasingly, on efforts to reduce forced displacement from organized crime, corrupt security forces, and extractive industries. However, in spite of repeated efforts by migrant rights and alternative rural development policy advocates to come together to develop a shared advocacy agenda, there has been a persistent disconnect (Ayón Citation2012; Fox 2006). An underlying cause of this divide may be that while migrant rights advocates represent those who have left, development policy advocates represent those who have stayed home.

Mexico’s persistent rural population

The empirical analysis that follows analyzes Mexican government census data in new ways to ask two related sets of empirical questions. First, to what degree has the rural percentage of Mexico’s population changed between 2000 and 2010? Because the government’s official definition of ‘rural’ – localities with fewer than 2500 inhabitants – is widely considered to be unrealistically low, this study addresses the question of ‘what counts’ as rural by developing a new indicator (see below). Based on this new indicator, the data analysis shows that the share of the national population living in predominantly rural municipalities decreased from 27% in 2000 to 25% in 2010, a small reduction compared to previous decades. Meanwhile, the absolute number of residents of predominantly rural municipalities increased during this period, reaching 28.3 million. This rural population is also geographically concentrated, with 74% residing in only ten states. Only two of those ten states are heavily dependent on migration. The second set of questions focuses on identifying cross-border migration trends within those predominantly rural municipalities by applying the government’s ‘migration intensity index’, a measure based on an extended survey that samples 10% of the population on international migration characteristics for the decennial census. The main empirical innovation here is to cross the data on persistent rurality with the data on evolving migration intensity, to show the extent and areas of overlap between these two trends.

The data analysis reveals two contradictory trends. First, it confirms an increased ‘nationalization’ of cross-border migration, from its original concentration in historic ‘sending’ regions to areas all across the country. The number of rural municipalities considered to have high migration intensity has increased. At the same time, it turns out that a majority of Mexico’s rural population lives in municipalities that are still not heavily dependent on cross-border migration. Specifically, 55% of the national population that still lives in predominantly rural municipalities are in areas that register low or very low levels of migration intensity.

This study’s analysis of census data demonstrates not only the persistent rurality of approximately one in four Mexicans; it also identifies the size and distribution of the rural population that has not yet fully integrated into the binational labor markets that have attracted extensive research attention from migration specialists (e.g. Massey et al. Citation1987; Massey, Goldring, and Durand Citation1994). The rationale for this empirical focus has three main elements. First, the persistence of Mexico’s rural population contradicts scholarly expectations and suggests the need for more research on the motivations and perceptions that shape the survival strategies of the rural population, as well as on how ‘actually-existing’ subnational labor and agricultural markets influence their decision-making. Second, the empirical focus on the size and distribution of the persistent rural population can inform alternative public policies that seek to retain rural jobs so that in the future, migration is a choice rather than an obligation. Third, though the research strategy employed here is primarily empirical, the approach is relevant to future conceptual work that can better articulate the fields of migration and development studies.

Historical trends in Mexico’s rural population

Demographers and historians use different thresholds to define ‘what counts’ as rural. The dominant Mexican governmental approach limits its definition of rural to very small localities, using a threshold of 2500 people. Others use 15,000 as the rural/urban cutoff, while there is also growing use of an intermediate, ‘mixed’ semi-rural category to account for small rural towns that do not fit neatly into either classification (OECD Citation2007). The brief historical overview that follows refers to both thresholds (2500 and 15,000), and the next section will introduce a new way of using Mexican census data to measure the rurality of the population.

After the end of Mexico’s radical reform government of the 1930s, the development model shifted from emphasizing agricultural development and land redistribution towards promoting industrial development and urbanization. Beginning in the 1940s, public investment, social spending, and urban-rural trade terms prioritized the growing cities and left most farmers behind, especially the vast majority dependent on rainfed agriculture. The government’s remaining investment in agriculture privileged irrigation infrastructure for small numbers of commercial producers, concentrated in only three northern states (Barkin and Suárez Citation1985). This shift dramatically affected the rural population. Between 1940 and the 1970s, more than 10,000 rural localities disappeared from the registry, the vast majority of which had 1000 or fewer inhabitants (Rodríguez and González Citation1988). The industrialization program known as ‘the Mexican miracle’ produced both push and pull factors that dislocated a substantial part of the rural population. By 1970, the population living in localities of fewer than 15,000 inhabitants had fallen to 53%. A decade later, Mexico was a primarily urban society, with 53% living in communities of more than 15,000 (Rodríguez and González Citation1988, 235). This data is associated with the structural changes indicated in , which shows that the sharpest drops in the agricultural share of employment occurred during the 1960s and 1970s. At the same time, Mexico’s accelerated urbanization process did not reduce the absolute size of the rural population, which increased by more than 10 million people between 1940 and 1970. Meanwhile, the gap within the rural population grew between subsistence and landless farmers on the one hand, and those with enough land to either be self-sufficient or grow a marketable surplus on the other. Semi-proletarian sub-subsistence producers became the majority (Paré Citation1977; CEPAL Citation1982). Only during a brief period under the Mexican Food System of 1980–1982 did national agricultural policy attempt to prioritize rainfed smallholders. The results were mixed because much of the increased public investment and subsidies went to better-off producers (Fox Citation1992).

Between the 1970s and 1985, the rural population increased by more than 6 million people and was geographically concentrated in the central, western, and southern areas of the country (Rodríguez and González Citation1988). Mexico’s rural population was influenced by fertility rates as well as out-migration trends. While decreasing national fertility rates in the 1980s and 1990s reduced the dependency ratio of children and the elderly, rural fertility rates remained high.Footnote12 The municipalities with high average fertility rates (3.5 children) are mainly located in the country’s mountainous regions, which include some of the most rural states such as Hidalgo, Puebla, Guerrero, and Oaxaca (Mier y Terán Citation2014).

Some demography experts treat ‘depeasantization’ – the shift away from family farming – as synonymous with ‘deruralization’ – the relocation to urban areas – though the 2000–2010 data indicate that Mexico’s declining levels of agricultural employment and the stabilization of the rural population, broadly defined, are trends that have become delinked (Aguilar and Graizbord Citation2014, 792). One reason for this is the increased integration of rural systems with their geographically immediate urban centers, which creates persistent rural communities amidst rapid urbanization (Appendini and Torres-Mazuera Citation2008; Torres-Mazuera Citation2012).

Internal migration rates also fell in recent decades, especially during Mexico’s transition to globalization (1985–1990) and the consolidation of trade liberalization (2005–2010) (Partida Bush Citation2014). While classic economic and sociological theories would lead one to expect that the internal migration from rural to urban areas would continue at high rates and the rural population would continue to drop, this did not happen (Partida Bush Citation2014). Rather, internal migration rates actually fell from a peak of 7.3 per 1000 inhabitants in 1980–1985 to 4.6 per 1000 in 2005–2010. Between 2010 and 2015, approximately 3.2 million Mexicans migrated internally, but rural-to-urban flows fell (Gordillo de Anda and Plassot Citation2017).

The rural population remains highly dispersed. According to the OECD, ‘24 million people live in more than 196,000 remote localities and an additional 13 million live in about 3000 rural, semi-urban localities’ of fewer than 15,000 inhabitants (Citation2007, 14). These small urban areas retain rural characteristics, such as low density and articulation with agriculture. The government’s 2500-inhabitant rural threshold, however, excludes many of these communities, which is why we propose an alternative indicator.

Methods: measuring the size of the rural population and ‘migration intensity’

The size and distribution of the rural population varies depending on how one defines rural communities.Footnote13 When one then tries to analyze rural population data through the lens of changing migration trends, the challenge is that the most robust official data for indicators of cross-border migration is limited to the municipal, rather than the community level. This is important because Mexican rural municipalities are districts of widely varying size and may include numerous villages. For example, an average municipal outmigration rate could reflect a combination of outlying villages with high outmigration rates and town centers with lower rates.

The primary unit of analysis used here to identify both rural and migration trends will be municipalities whose majority population lives in communities of fewer than 5000 inhabitants. This approach allows for the inclusion of numerous municipalities that may have an urban core of more than 5000 but whose population majority lives in rural villages. According to the government’s criteria for defining rurality, such municipalities would count as urban. The approach adopted here reflects a compromise effort to define rurality as falling between the too-low official cutoff of 2500 and the semi-urban cutoff of 15,000 inhabitants cited above.

Since we are interested in documenting the relationship between rurality and migration trends, we analyze the distribution and concentration of the rural population using a national municipal database based on the 2000 and 2010 censuses. We focus on this period because this is the decade that experienced the first sustained decrease in the annual immigration flows from Mexico to the United States, as shown in . This study’s database combines an official composite index that measures ‘migration intensity’ published by the National Population Council (CONAPO) with the population living in what we call ‘predominantly rural’ municipalities. This analysis categorizes municipalities as ‘predominantly rural’ if at least 50% of the total population lives in communities with fewer than 5000 inhabitants in both the 2000 and 2010 censuses.

Using this index to identify predominantly rural municipalities, our analysis finds that the rural share of the national population fell from 27% to 25% between 2000 and 2010.Footnote14 At the same time – and in contrast to analyses cited above that use the lower official cutoff of 2500 inhabitants – the national rural population increased in absolute terms, from 26.7 million in 2000 to 28.3 million in 2010 (See ). The main finding in this 2000–2010 comparison is that the national rural population held remarkably steady, both in relative and absolute size, in spite of the dislocation in agricultural employment.

Table 1. 10 States with the largest absolute population in municipalities that are predominantly rural 2000-2010.

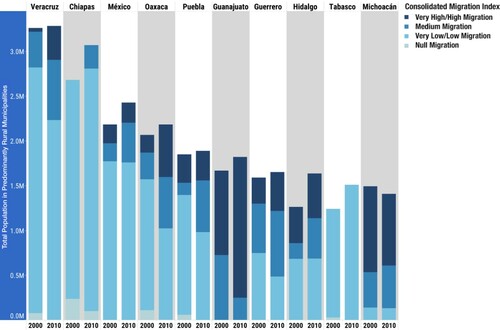

One of the most notable empirical findings here is that the national rural population is highly geographically concentrated. In 2010, 74% of the population living in predominantly rural municipalities was concentrated in only ten states: Veracruz, Chiapas, Estado de México [State of Mexico], Oaxaca, Puebla, Guanajuato, Guerrero, Hidalgo, Tabasco, and Michoacán (see and ). Even more remarkable is the finding that 47% of the national population living in predominantly rural municipalities were clustered in only five states. If one looks at these states through the lens of their urban/rural composition, as shown in , two are also very urban (Estado de México and Puebla), while the state with the largest rural population is also majority urban (Veracruz). Yet, as the work of Torres-Mazuera (Citation2012, Citation2013) and Appendini and Torres-Mazuera (Citation2008) suggests, rural spaces across the country have reconfigured their geopolitical and territorial boundaries by adapting their subsistence strategies while local power shifts from agrarian authorities towards municipal governance structures. This has led to rural livelihoods becoming increasingly articulated with urban areas, as is the case in the Estado de México.

Figure 3. Mexico’s population in rural municipalities: Top ten states (2010).

Note: Each state’s percentage refers to its share of the national rural population. Source: Map elaborated by the authors with CONAPO data. This map shows the percentage of the national population living in municipalities where at least 50% of the total population lives in localities with fewer than 5000 inhabitants.

After identifying the size and geographic distribution of the rural population at the national and state levels, the next step in this analysis is to address the relationship between rurality and cross-border migration. While the rural share of out-migration has fallen over time, the distribution of communities of origin has clearly diversified geographically. Historically, they were concentrated in a relatively small number of ‘traditional’ sending states in the center-west of the country, whereas now migrants are originating from rural and urban regions across the entire country (e.g. Cornelius, Fitzgerald, and Fischer Citation2007; Davis and Eakin Citation2013; Fox and Rivera-Salgado Citation2004; Hernández-León Citation2008). The empirical goal here is identify the degree to which predominantly rural municipalities have become more dependent on migration.

The CONAPO migration intensity index is based on an extended survey that samples 10% of the population interviewed for the decennial census. It aims to capture both international migrants who had left the country and those who returned to Mexico after living in another country (CONAPO Citation2010). We utilize CONAPO’s municipal level indicators of migration intensity. The main strength of this index is its combination of four important indicators to measure variation in migration intensity: remittances, emigrants, circular migrants, and returned migrants (See ).

Table 2. CONAPO migration intensity index.

This index assesses municipal migration intensity in terms that range from ‘null,’ ‘very low,’ ‘low,’ ‘medium,’ ‘high,’ and ‘very high.’ These different levels allow for a comparison of changing degrees of dependence on migration from 2000 to 2010. While this index does not offer information at the more granular village level – and definitely undercounts entire families that have left – the index is built with extended survey sampling of national census information and includes information by all municipalities in the country, which allows for national comparisons across municipalities.Footnote15 While the migration intensity indicators’ capacity to capture absolute levels of cross-border migration dependency is limited, their nationwide consistency still captures subnational and local variation in relative degrees of migration intensity.Footnote16

Results

After crossing CONAPO’s migration intensity index with the database of predominantly rural municipalities, we find that 55% of the national rural population still lives in municipalities with low levels of trans-border migration dependency (see ). This represents a notable drop compared to 2000, when 62% of the rural population lived in municipalities with low migration rates. The data also shows that the population living in rural municipalities with intermediate levels of migration grew from 17% to 20%, while the population in rural municipalities registering high levels of migration increased from 21% to 25%. Yet when one looks at these trends in terms of spatial distribution, only two of the ten states with the largest concentrations of rural populations in 2010 show high or very high dependency on international migration (Michoacán and Guanajuato). Both are in the center-west, Mexico’s historic sending region (see ).

Figure 4. Population in Predominantly Rural Municipalities by Degree of International Migration Intensity. Source: Authors’ analysis of rural population by migration index based on CONAPO data.

Figure 5. 2000–2010 Changes in Migration Intensity in Rural Municipalities in Mexico’s Largest Rural Population States. Source: Authors’ elaboration with CONAPO data. Chart represents the sum of the population totals for each census year.

Overall, 36% of the predominantly rural municipalities (879) increased their international migration levels between 2000 and 2010. This is strong evidence of the nationwide diffusion of what many migration scholars used to see as a regionally concentrated phenomenon in historic ‘sending’ states. Yet this relative increase in the number of rural municipalities with increased migration did not necessarily involve high absolute levels of out-migration, since many of those municipalities increased their US migration rates from non-existent (null) to low (as indicated in and ). By 2010, only 11 predominantly rural municipalities in the states of Veracruz, Chiapas, Oaxaca, and Tabasco showed a null level of migration, down from 88 in 2000. By 2010, less than 1% of rural municipalities registered null migration indexes, while many of those that had very low levels moved up to low levels, and many with low levels in 2000 moved up to medium levels in 2010 (See ). At the same time, 51% of all rural municipalities maintained the same migration intensity index during this period. This relative stability, in addition to the nationwide reduction of net international migration to zero, suggests that this share of more stable municipalities may not change dramatically when the 2020 census results are reported.

The most significant finding of this exercise is that while migration dependency certainly diversified geographically between 2000 and 2010, a very substantial share of Mexico’s rural population is not yet heavily dependent on international migration. If one focuses on the top five states where almost half of Mexico’s rural people live (47% of the total in 2010), 69% of these states’ rural residents still live in null, low, or very low migration municipalities. This rate of municipal-level migration dependence is substantially lower than the national average level of migration dependency in rural municipalities. This is strong evidence of a geographically concentrated pattern of persistent rurality.

shows that two of Mexico’s top five states with the highest share of rural population experienced significant shifts towards greater migration dependence; these two states alone account for 23% of the national rural population – Veracruz and Chiapas. In Veracruz, the state with the largest rural population, the share with high/very high migration rates increased dramatically, though that segment still represented only 12% of the state’s rural population. Calculating the Veracruz rural population living in both high and medium outmigration municipalities, we find that it doubled, rising from 14% to 32%. Yet 68% of Veracruz’s rural population continued to live in municipalities with low, very low, or null migration rates.

Chiapas, which ranks second in terms of rural inhabitants and which had the lowest prior levels of migration, also experienced significant growth in its population living in medium-level outmigration municipalities. Yet 92% of the state’s rural population continued to live in municipalities with low, very low, or null migration rates. Rural residents of the Estado de México, located close to Mexico City, have access to more urban and peri-urban job opportunities than any of the other states with large rural populations, so their residents have more alternatives to cross-border migration. The state of Oaxaca experienced one of the most significant changes between 2000 and 2010, with the share of the rural population living in either medium or high outmigration municipalities growing from 24% to 53%. However, almost half of the state’s rural population continued to live in low migration municipalities. Puebla, Mexico’s fifth-ranking state in terms of rural inhabitants, experienced a similar pattern. The share of rural inhabitants in medium, high, and very high migration municipalities almost doubled, from 25% to 48% of the total rural population in the state. Only two of Mexico’s top ten states with the highest share of rural population, Guanajuato and Michoacán – together containing 11% of the national rural population – were predominantly high-outmigration states. The differences between these two states, which are both in Mexico’s historic ‘sending’ region of the center-west, and the other high rural population ‘new sending’ states remained very significant in 2010. The question remains whether the 2020 census will show the gap between them closing.

This concentration of a large share of Mexico’s persistent rural population in a relatively small number of states also has a clear ethnic dimension. Of the 28.3 million rural residents in 2010, 6.6 million people (23.3%) lived in ‘indigenous households.’ Nationwide, 10.7 million people lived in indigenous households in 2010. The census defined these households as families in which at least one parent spoke an indigenous language – a more restrictive category than the recently added ethnic self-identification category, but a broader definition than in earlier censuses.Footnote17 Of the population living in indigenous households, 61% lived in predominantly rural municipalities (according to our definition of rurality).Footnote18 In brief, Mexico’s indigenous population remains predominantly rural, while the rural population as a whole is disproportionately indigenous.Footnote19

Bringing the data on ethnicity together with rurality and migration trends shows that Mexicans who are remaining rural are disproportionately indigenous. In 2010, almost three quarters of Mexico’s rural indigenous population lived in municipalities that had not yet become heavily dependent on international migration. Specifically, 74% of the rural indigenous population continued to live in predominantly rural municipalities that registered low, very low, and null migration intensity rates (in contrast to the nationwide figure of 55%). In terms of the population as a whole, of the 15.5 million people living in predominantly rural municipalities with null, very low, and low migration rates, 31.4% are indigenous.

In brief, this synthesis of 2010 data on rurality, migration and ethnicity found that the majority of the indigenous population continued to be rural; almost one quarter of the persistent rural population was indigenous; one third of the rural population in low migration areas was indigenous and almost three quarters of the rural indigenous population lived in areas that are not yet very dependent on international migration. This pattern does not seem likely to change significantly before the 2020 census.

Discussion

These empirical findings raise a series of analytical questions that both rural field research and the 2020 census may help to answer:

How have regional urban-rural labor markets changed? How does extra-local migration or commuting influence social, civic, and political life? Do these extra-local family employment strategies strain the rural, social, and civic fabric, or do they permit the persistence of rural community in spite of the lack of sustainable local employment?

The 2000–2010 patterns indicate that rural regions with similar social indicators can experience very different levels of out-migration. The conventional explanation of such variation in the migration literature focuses on historical path-dependence, which generates the legacies of social networks that enable migration. Can development studies shed light on other factors at work? How can research more effectively articulate structural factors and agency in order to test the hypothesis proposed here: that persistent rurality is evidence of the exercise of ‘the right to stay home?’

What are the main characteristics of rural regions with persistently low out-migration? Can comparative analysis of different regions help both to identify which structural factors are most significant as well as determine whether agency may be relevant? Specifically, might policy decisions or the agency of broad-based social organizations help to explain regional differences? After all, rural Mexico is characterized by an archipelago of scaled-up regional social organizations that have sustained numerous social enterprises with the potential to scale up their job-creating initiatives.Footnote20

How do ethnic differences influence migration patterns? Within states, most high-migration rural regions are not predominantly indigenous, in contrast to most of the very low and low migration regions (Oaxaca is an exception). How do those indigenous regions that have become heavily involved in cross-border migration differ, and what are the implications for regions that appear to be moving in that direction?

This study does not address a major issue that challenges the right to stay home: the rise of forced displacement over the past two decades. Two main factors are at work. First is the colonization of rural areas by organized crime, which has displaced the state as the principal source of coercive authority in large parts of rural Mexico (Trejo Citation2014; Trejo and Ley Citation2018). The second main driver of displacement involves extractive industries, especially mining. International mining corporations, which present themselves as transparent economic investors, also may be involved in negotiations with drug cartels to speed up the displacement process in targeted states with significant rural population such as Zacatecas and Sinaloa (Garibay et al. Citation2011; Lohmuller Citation2015). The visible presence of internally displaced people in large cities and at the US border is dramatic, and human rights groups are beginning to produce regular reports (CMDPDH Citation2019). Because of ineffective government action to address organized crime and the impunity with which it operates – as well as continued government support for extractive industries – rural forced displacement appears to have spiked in the past decade (Alvarado Citation2015; Cantor Citation2014; Bada and Feldmann Citation2019; Gil Olmos Citation2016; Rubio Díaz-Leal and Pérez Citation2015). In 2014 government surveys, 6% of interstate migrants reported that public insecurity and violence were the primary reasons for their decision to migrate (Gordillo de Anda and Plassot Citation2017).

Whether forced displacement reaches a scale that will register in the national demographic data is not clear (Martínez Citation2014; Wood et al. Citation2010), but some conservative unofficial estimates calculate that between 2006 and 2018, 300,000 people were displaced by violence (Hernández García Citation2020). The International Displacement Monitoring Centre recently reported a similar estimate of 345,000, noting that Mexico does not have an official registry of internally displaced people (IDMC Citation2020, 54, 103). Moreover, we should also note that forced displacement driven by crime and violence occurs in urban areas as well.

Conclusion

This study’s principal finding is empirical, documenting the significant absolute size and geographic concentration of Mexico’s persistent rural population. The top ten states in terms of rural population experienced two simultaneous trends. First, there were significant increases in the share of the population living in medium or high outmigration municipalities – though starting from a low baseline in eight of the top ten states. Meanwhile, most of the rural population continued to live in municipalities with low or very low dependency on cross-border migration. Indeed, by 2010, net cross-border migration had slowed dramatically, especially when compared to the 1990s. When seen through the lens of long-term structural change, the historic decline in the rural share of the population has slowed significantly, as has the pace of decline in the agricultural share of the economically active population and the rate of outmigration to the United States. The rate of domestic, inter-regional migration also slowed during this period, as metropolitan urban areas reached a saturation point and ceased attracting as many industrial jobs.

According to the 2010 census, approximately one-quarter of Mexico’s national population continued to live in hamlets, villages, and small rural towns. While most of these residents did not earn the majority of their income from farming, and many were integrated into nearby regional or urban wage labor markets, one could argue that this persistent rural population has in effect exercised their ‘right to stay home.’ This occurs in spite of the absence of governmental policies that actively promoted sustainable employment. Furthermore, rural inhabitants have exercised their right to stay home even as the Mexican government has not put sustainable rural development at the center of its public policy agenda. Instead, at least until 2018, it focused on public policies privileging international migration and family remittances and government social programs emphasizing transfer payments.

One might ask whether the 2020 census will capture changes resulting from the 2018 political shift in Mexico, especially in light of the new president’s comments that migration should be a choice rather than an obligation. Yet despite these remarks, the violence that is driving forced displacement continued unabated during the López Obrador government’s first two years. Perhaps more significant in terms of the number of rural inhabitants directly affected was a new economic policy that emphasized budget austerity and large, capital-intensive mega-projects. At the same time, the López Obrador administration also made major changes to national agricultural policy, cutting or eliminating numerous subsidy programs that either had been biased towards large growers or were prone to corruption, and the budget for the largest single pro-smallholder program was increased in 2020.Footnote21 These changes may shift agricultural spending in a pro-poor direction. However, since the overall agricultural budget was also cut sharply, it is not yet clear to what degree public spending and investment in family farmers actually increased. Social organizations of the rural poor that had spent decades building scaled-up economic enterprises were not funded, since the government’s social policy emphasized direct transfer payments to individuals rather than investments in job creation by social enterprises (Mendoza Citation2019). This suggests that government social spending is unlikely to create sustainable rural employment.

At the same time, the trend in reduced migration to the United States has continued, with a contraction in the US labor market and a sharp increase in the risks and costs involved in crossing the border without documents. The implications for the migration and rural population trends to be reported in the 2020 census remain to be seen, especially since data-gathering was impacted by COVID-19.Footnote22 The arrows point in both directions. On the one hand, the 2018–2020 period saw few contextual changes that would strengthen ‘the right to stay home’ by making such an option more viable; on the other, changes in the US context made cross-border employment options, and thus migration, less viable as well.

To conclude, what is the significance of these findings of persistent rurality in light of the many predictions of radical depopulation made during the NAFTA debate more than twenty-five years ago? We can affirm that post-NAFTA, rural and agricultural are no longer synonymous, and agricultural employment was indeed hollowed out. Nonetheless, millions of Mexican families preferred to remain in their communities rather than embrace the prospect of urban insecurity and alienation or risk dangerous border-crossing. In spite of so many powerful ‘push’ factors, rural agency appears to have thrown sand in the machinery of structural determinism and rural depopulation.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kirsten Appendini, Jorge Durand, Margarita Flores and three anonymous reviewers for helpful feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Xóchitl Bada

Xóchitl Bada is an Associate Professor in Latin American and Latino Studies at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Her articles have appeared in Forced Migration Review, Population, Space, and Place, Latino Studies, and Labor Studies Journal. She is the author of Mexican Hometown Associations in Chicagoacán: From Local to Transnational Civic Engagement (Rutgers University Press, 2014). She is co-editor of the books New Migration Patterns in the Americas. Challenges for the 21st Century (Palgrave, 2018), Accountability across Borders: Migrant Rights in North America (The University of Texas Press, 2019), and the Oxford Handbook of Sociology of Latin America (2020).

Jonathan Fox

Jonathan Fox is a Professor in the School of International Service at American University, where he directs the Accountability Research Center. His research addresses collective action, transparency and accountability. His recent articles have been published in World Development, Journal of Peasant Studies and IDS Bulletin. His books include: Subsidizing Inequality: Mexican Corn Policy Since NAFTA, Accountability Politics: Power and Voice in Rural Mexico, and Mexico’s Right-to-Know Reforms: Civil Society Perspectives. He works closely with public interest groups, social organizations, private foundations and policymakers. He serves on the boards of directors of Fundar, Controla tu Gobierno, and Community Agroecology Network.

Notes

1 Bartra (Citation2008) and Bacon (Citation2013) then translated the phrase into more colloquial English as ‘the right to stay home.’

2 This article continues a line of research that began with the observation that the relationship between migration intensity and poverty rates was not as direct as had been widely assumed. In earlier studies, we showed that by 2000 only about 20% of rural municipalities combined high poverty levels with medium, high, and very high degrees of ‘migration intensity’. As a result, we began to explore the relationship between migration intensity and agricultural employment (Fox and Bada Citation2008; Fox Citation2013; Bada and Fox Citation2014).

3 This interpretation, with its emphasis on agency, has implications for the literature that emphasizes long-term structural changes and report a ‘disappearing peasantry’ (e.g., Bryceson, Kay, and Mooij Citation2000 and Damian and Pacheco Citation2006). While this literature concentrates on rural class analysis, the focus here is on persistent rurality.

4 Macroeconomic modelers from different perspectives agreed on this point (Levy and van Wijnbergen Citation1992 and Robinson et al. Citation1991). Agricultural economists, in contrast, noted that though most Mexican farmers grew corn, most were not surplus-producers and grew mainly for household consumption – and therefore would not be directly hit by NAFTA’s opening of trade and expected producer price drops (de Janvry, Sadoulet, and de Anda Citation1995). Mexico’s subsequent major drop in agricultural employment was closer to the pessimistic predictions. Indeed, Mexico’s post-NAFTA opening to corn imports was exacerbated by both the government’s abandonment of the gradual phase-in allowed by the agreement and the US government’s substantial ‘dumping’ of economic support for corn exports (Nadal Citation2002; Wise Citation2010a, Citation2010b). This raises important questions about how producer prices affect the majority of smallholder corn growers who are not net surplus-producers. See Hewitt de Alcántara (Citation1994), Eakin et al. (Citation2014) and Appendini (Citation2014).

5 As one of this paper’s authors noted at the time, these predictions were reminiscent of government critics’ predictions two decades earlier regarding the inexorable proletarianization of the peasantry: ‘They underestimated the capacity of the peasantry to resist full displacement. Protest drove renewed state intervention to subsidize the better-off third of the ejido [agrarian reform] sector and campesino identity turned out to be more resilient than predicted’ (Fox Citation1994, 245).

6 On that protest wave, which involved a broad spectrum of peasant organizations, see Sánchez Albarrán (Citation2007).

7 The government’s modest trade compensation payment program for farmers, originally called Procampo, was at least statistically associated with small reductions in migration (Cuecuecha and Scott Citation2010). This finding underscores the potential for a more ambitious and better-targeted approach.

8 This survey included both documented and undocumented emigrants to the United States. The composition of Mexican migration to the United States shifted from a predominantly rural origin to a mixed rural-urban origin in the 1990s (EMIF Citation2013). The share of the rural population crossing to the United States has diminished steadily. Between 2000 and 2011, the average share of border-crossers of ‘non-urban’ origin was 43%. By 2017, the ‘non-urban’ share of border-crossers fell to 12.5% (EMIF Norte Citation2013, Citation2017). EMIF defines ‘non-urban’ as population centers of less than 15,000 inhabitants.

9 In 2000, the average cost of an unauthorized border crossing was USD $2273. The average cost steadily rose and by 2017, it reached USD $7002, representing an increase of 820% since 1985 in 2018 USD (Massey Citation2020).

10 Consider these search findings: in the entire collection of the Journal of Peasant Studies since 1973, the word ‘migration’ appears in only 23 article titles, 19 keywords, and only 992 times in all article texts. In the Journal of Agrarian Change, ‘migration’ appears only 10 times in titles, 15 times in keywords and 399 times in the entire text since 2001. In the International Migration Review, ‘rural development’ appears only in 3 article titles and 179 times in all article text since 1966. In the Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, ‘rural development’ appears 1 time in article titles, 2 keywords, and only 46 times in all article text since 1998.

11 This phrase refers to Hirschman’s (Citation1970) classic ‘exit, voice and loyalty’ conceptual framework. For applications to Mexican migrant associationalism, see Fox (Citation2007) and Duquette-Rury (Citation2019).

12 The urban-rural gap has decreased over time but has yet to close. The marital total fertility rate in rural areas dropped from 10.6 in 1970 to 7.4 in 1982, a decline of 2.5% annually (García y Gama Citation1989). By 2008, women living in rural communities had an average of 2.7 children compared to 2 children among urban women (Sánchez and Pacheco Citation2012).

13 While rural and agricultural are often treated as synonyms, in Mexico those two categories have increasingly diverged (Appendini and Torres-Mazuera Citation2008). For two decades, non-farm income has outpaced farm income in rural Mexico, increasing from 43% of total rural income in 1997 to 67% in 2003 (Scott Citation2010; Haggblade, Hazell, and Reardon Citation2007).

14 In comparison, according to official census calculations, the rural share of the population fell from 25 to 22% when measured by localities with fewer than 2500 inhabitants (INEGI Citation2010).

15 One weakness of the index is that because its level of analysis is the municipality (a district or a county) rather than the smaller units of localities (which often include many outlying villages), disproportionally large municipal population centers could have led us to characterize too many municipalities as predominantly rural. To address this issue, we analyzed all our municipalities selected as predominantly rural whose total population was above 50,000 inhabitants (less than 7% of our municipalities selected for both decennial counts) to make sure that the majority of these municipalities did not have large urban centers (municipal centers larger than 15,000). Since we confirmed that they did not indeed have such urban centers, we included all municipalities that passed our first methodological filter regardless of total municipal population size.

16 For a useful critique of the index, see Andrews (Citation2016).

17 In 2010, the census criteria for measuring indigeneity broadened to count the population living in indigenous households. For most of the twentieth century, the official census criterion was self-reported command of an indigenous language. The 2000 census also allowed self-identification, a concept that was broadened in 2010 – leading to a near-tripling of the indigenous share of the national population to 15%. For demographic analysis of recent changes in census measurement of ethnicity, see Granados Alcantar and Quezada Ramírez (Citation2018) and Vásquez Sandrin (Citation2015). The 2010 census also allowed for an expansion of the language criteria to count the entire family as indigenous if a parent spoke an indigenous language. See: https://www.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/olap/Proyectos/bd/censos/cpv2010/Hogares.asp?s=est&c=28037&proy=cpv10_hogares. According to 2015 census data, 21.5% of the population self-identified as indigenous, while 10.1% were identified as indigenous based on language (Numeralia Indígena Citation2015, 22).

18 Note that this study’s focus on indigenous households in predominantly rural municipalities is distinct from the government’s category of ‘indigenous municipalities,’ those with at least 40% of the population identified as indigenous (based on language criteria).

19 Methodological note: It is possible that the census overstates the rural share of the indigenous population because it undercounts indigenous migrants living in cities. This issue has not been studied systematically – but if that were the case, it would affect the rural share of a larger total national indigenous population. As a result, this recognition of a larger urban indigenous population would not affect the indigenous share of the rural population emphasized here.

20 For overviews of consolidated, autonomous regional rural social organizations and their diverse social enterprises, see Bartra et al. (Citation2014), Flores and Rello (Citation2002), and Tello and Bartra (Citation2000), among others. For background on the origins of this ‘social sector’ in the 1980s and the idea of ‘appropriating the productive process,’ see Bartra et al. (Citation1991); Fox (Citation2007); Moguel, Botey, and Hernández (Citation1992) and Paré et al. (Citation1997).

21 See Subsecretaría de Alimentación y Competitividad (Citation2019, Citation2020). The Agriculture Ministry’s overall budget was cut 31% from 2019 to 2020. Spending for the largest pro-smallholder program, Producción para el Bienestar, was increased by 16.7%, payments were capped at 20 hectares and coverage was expanded to include 250,000 previously-excluded indigenous producers. This program was first called Procampo, then ProAgro (Cuecuecha and Scott Citation2010; Fox and Haight Citation2010; Scott Citation2010).

22 Thanks to Dr. Margarita Flores for sharing this observation. The shift to census self-reporting in March 2020 is likely to lead to rural under-reporting.

References

- Aguilar, A. G., and B. Graizbord. 2014. “La distribución espacial de la población, 1990-2010: cambios recientes y perspectivas diferentes.” In Los mexicanos. Un balance del cambio demográfico, edited by C. Rabell Romero, 783–823. Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

- Alarcón, R. 2002. “The Development of the Hometown Associations in the United States and the Use of Social Remittances in Mexico.” In Sending Money Home: Hispanic Remittances and Community Development, edited by R. de la Garza and L. Lowell, 101–124. New York: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Alvarado, I. 2015. “Sin asilo y sin esperanza: Cientos de mexicanos huyen de la violencia.” La Opinión, October 27. http://laopinion.com/2015/10/26/sin-asilo-y-sin-esperanza-cientos-de-mexicanashuyen-de-la-violencia/.

- Andrews, A. 2016. “Legacies of Inequity: How Hometown Political Participation and Land Distribution Shape Migrants’ Paths Into Wage Labor.” World Development 87: 318–332.

- Aparicio, F. J., and C. Meseguer. 2012. “Collective Remittances and the State: The 3X1 Program in Mexican Municipalities.” World Development 40 (1): 206–222.

- Appendini, K. 2014. “Reconstructing the Maize Market in Rural Mexico.” Journal of Agrarian Change 14 (1): 1–25. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/https://doi.org/10.1111/joac.12013.

- Appendini, K., and G. Torres-Mazuera, eds. 2008, ¿Ruralidad sin agricultura? Mexico City: El Colegio de Mexico.

- Arias, P. 2009. Del arraigo a la diáspora. Dilemas de la familia rural. Guadalajara: Universidad de Guadalajara-Miguel Ángel Porrúa.

- Ayón, D. 2012. Linking Development and Migration: A Mexico-US Dialogue. Washington, DC: Wilson Center, Mexico Institute, March. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/media/uploads/documents/Linking%20Development%20%26%20Migration.pdf.

- Bacon, D. 2013. The Right to Stay Home: How US Policy Drives Mexican Migration. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Bada, X. 2014. Mexican Hometown Associations in Chicagoacán. From Local to Transnational Civic Engagement. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

- Bada, X. 2016. “Collective Remittances and Development in Rural Mexico: A View from Chicago’s Mexican Hometown Associations.” Population, Space and Place 22 (4): 343–355.

- Bada, X., and A. E. Feldmann. 2019. “How Insecurity Is Transforming Migration Patterns in the North American Corridor: Lessons from Michoacán.” In New Migration Patterns in the Americas: Challenges for the 21st Century, edited by A. E. Feldmann, X. Bada, and S. Schütze, 57–83. Cham: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Bada, X., and J. Fox. 2014. “Patrones migratorios en contextos de ruralidad y marginación en el campo mexicano 2000-2010: Cambios y continuidades.” Revista ALASRU: Análisis Latinoamericano del Medio Rural 10: 277–295. https://jonathanfoxucsc.files.wordpress.com/2011/11/bada_fox_patrones_migratorios_alarsu_2014.pdf.

- Barkin, D., and B. Suárez. 1985. El fin de la autosuficiencia alimentaria. Mexico: Centro de Ecodesarrollo/Océano.

- Bartra, A., et al. 1991. Los nuevos sujetos del desarrollo rural. Cuadernos desarrollo de base, No. 2.

- Bartra, A. 2003. Cosechas de ira: Economía política de la contrareforma agraria. México: Itaca/Instituto Maya.

- Bartra, A. 2008. “The Right to Stay: Reactivate Agriculture, Retain the Population.” In The Right to Stay Home. Alternative to Mass Displacement and Forced Migration in North America, 18–25. San Francisco, CA: Global Exchange. https://www.scribd.com/document/10500581/The-Right-to-Stay-Home-Web-FINAL.

- Bartra, A., et al. 2014. Haciendo milpa: Diversificar y especializar: estrategias de organizaciones campesinas. Mexico: Circo Maya/Itaca.

- Borbolla, K. 2019. AMLO busca que la migración sea optativa. Debate, January 7. https://www.debate.com.mx/politica/AMLO-busca-que-la-migracion-sea-optativa-20190107-0051.html.

- Bryceson, D., C. Kay and J. Mooij. 2000. Disappearing Peasantries: Rural Labour in Africa, Asia and Latin America. London: Intermediate Technology Publications.

- Çağlar, A. 2006. “Hometown Associations, the Rescaling of State Spatiality and Migrant Grassroots Transnationalism.” Global Networks 6 (1): 1–22.

- Cantor, D. J. 2014. “The New Wave: Forced Displacement Caused by Organized Crime in Central America and Mexico.” Refugee Survey Quarterly 33: 34–68.

- Castles, S. 2009. “Development and Migration – Migration and Development: What Comes First? Global Perspective and African Experiences.” Theoria. A Journal of Social and Political Theory 56 (121): 1–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.3167/th.2009.5612102.

- CEPAL (Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe). 1982. Economía campesina y agricultura empresarial. Mexico: Siglo XXI.

- CMDPDH (Comisión Mexicana de Defensa y Promoción de los Derechos Humanos). 2019. Episodios de desplazamiento interno forzado masivo en México. Informe 2018. Mexico: Comisión Mexicana de Defensa y Promoción de los Derechos Humanos. http://cmdpdh.org/project/episodios-de-desplazamiento-interno-forzado-masivo-en-mexico-informe-2018/.

- CONAPO (Consejo Nacional de Población). 2010. Anexo C. Metodología del Índice de Intensidad Migratoria México-Estados Unidos. Mexico: Secretaría de Gobernación. Consejo Nacional de Población. http://www.conapo.gob.mx/work/models/CONAPO/intensidad_migratoria/anexos/Anexo_C.pdf.

- CONAPO (Consejo Nacional de Población). 2015. “Cambio en la intensidad migratoria en México, 2000–2010.” Boletín de migración internacional, 3(3), August.

- Cornelius, W., D. Fitzgerald, and P. L. Fischer, eds. 2007. Mayan Journeys: The New Migration from Yucatán to the United States. La Jolla: Center for Comparative Immigration Studies, University of California, San Diego.

- Cornelius, W., and P. Martin. 1993. “The Uncertain Connection: Free Trade and Rural Mexican Migration to the United States.” International Migration Review 27 (3): 484–512.

- Cuecuecha, A., and J. Scott. 2010. The Effect of Mexican Agricultural Subsidies on Migration and Agricultural Employment. Woodrow Wilson Center, Mexico Institute, Mexican Rural Development Research Reports, No. 3.

- Damian, A., and E. Pacheco. 2006. “Employment and Rural Poverty in Mexico.” In Peasant Poverty and Persistence in the 21st Century: Theories, Debates, Realities and Policies, edited by J. Boltvinik, and S. A. Mann, CROP, 206–243. London: Zed Press.

- Davis, J., and H. Eakin. 2013. “Chiapas’ Delayed Entry into the International Labour Market: A Story of Peasant Isolation, Exploitation, and Coercion.” Migration and Development 2 (1): 132–149.

- De Haas, H. 2005. “International Migration, Remittances and Development: Myths and Facts.” Third World Quarterly 26 (8): 1269–1284.

- de Janvry, A., K. Emerick, M. Gonzalez-Navarro, and E. Saudoulet. 2013. Delinking Land Rights from Land Use: Impact of Certification on Migration and Land Use in Rural Mexico. http://www.ocf.berkeley.edu/~kemerick/certification_and_migration.pdf.

- de Janvry, A., E. Sadoulet, and G. Gordillo de Anda. 1995. “NAFTA and Mexico’s Maize Producers.” World Development 23 (8): 1349–1362.

- De la Garza, R. O. 2013. “The Impact of Migration on Development: Explicating the Role of the State.” In New Perspectives on International Migration and Development, edited by J. Cortina, and E. Ochoa-Reza, 43–66. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Delgado Wise, R., and H. Márquez Covarrubias. 2009. “Understanding the Relationship between Migration and Development: Toward a New Theoretical Approach.” Social Analysis 53 (3): 85–105.

- Delgado Wise, R., and H. Veltmeyer. 2016. Agrarian Change, Migration and Development. Black Point: Fernwood.

- Duquette-Rury, L. 2019. Exit and Voice. The Paradox of Cross-Border Politics in Mexico. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Eakin, H., H. Perales, K. Appendini, and S. Sweeney. 2014. “Selling Maize in Mexico: The Persistence of Peasant Farming in an Era of Global Markets.” Development and Change 45 (1): 133–155. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12074.

- EMIF Norte (Encuesta sobre migración en la Frontera Norte de México). 2013. Serie anualizada 2004 a 2011. Mexico: Secretaría de Gobernación/Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores/Secretaría del Trabajo y Previsión Social/El Colegio de la Frontera Norte.

- EMIF Norte (Encuesta sobre migración en la Frontera Norte de México). 2017. Tabulados básicos. Migrantes Procedentes del Sur. Cuadro 6.1.1. Mexico: Secretaría de Gobernación/Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores/Secretaría del Trabajo y Previsión Social/El Colegio de la Frontera Norte.

- Fairbairn, M., J. Fox, S. R. Isakson, M. Levien, N. Peluso, S. Razavi, I. Scoones, and K. Sivaramakrishnan 2014. “Introduction: New Directions in Agrarian Political Economy.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 41 (5): 653–666.

- Fajnzylber, P., and H. J. López. 2007. Close to Home. The Development Impact of Remittances in Latin America. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Flores, M., and F. Rello. 2002. Capital Social Rural: Experiencias de México y Centroamérica. Mexico: CEPAL/UNAM/Plaza y Valdés.

- Fox, J. 1992. The Politics of Food in Mexico: State Power and Social Mobilization. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. https://jonathanfoxucsc.files.wordpress.com/2018/12/Fox_The_Politics_of_Food_in_Mexico.pdf.

- Fox, J. 1994. “Political Change in Mexico's New Peasant Economy.” In The Politics of Economic Restructuring: State-Society Relations and Regime Change in Mexico, edited by M. L. Cook, K. J. Middlebrook, and J. Molinar, 243–276. La Jolla: UCSD, Center for U.S.- Mexican Studies. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/84t497rz.

- Fox, J. 2007. Accountability Politics: Power and Voice in Rural Mexico. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fox, J. 2013. Las políticas públicas hacia la agricultura y su relación con el empleo. In OXFAM México, El derecho a la alimentación en México: Recomendaciones de la sociedad civil para una política pública efectiva, México, October. http://oxfammexico.org/crece/el-derecho-a-la-alimentacion-en-mexico-recomendaciones-de-la-sociedad-civil-para-una-politica-publica-efectiva/.

- Fox, J., and X. Bada. 2008. “Migrant Organization and Hometown Impacts in Rural Mexico.” Journal of Agrarian Change 8 (2-3): 435–461. http://escholarship.org/uc/item/7jc3t42v.

- Fox, J., and L. Haight, eds. 2010. Subsidizing Inequality: Mexican Corn Policy since NAFTA. Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars/CIDE/UC Santa Cruz. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/subsidizing-inequality-mexican-corn-policy-nafta.

- Fox, J., and G. Rivera-Salgado, eds. 2004. Indigenous Mexican Migrants in the United States. La Jolla: Center for U.S. Mexican Studies and Center for Comparative Immigration Studies. University of California, San Diego.

- García y Gama, I. O. 1989. “La fecundidad en las áreas rurales y urbanas de México.” Estudios demográficos y urbanos 4 (1): 53–74.

- García Zamora, R. 2005. Collective Remittances and the 3×1 Program as a Transnational Social Learning Process. Presented at Mexican Migrant Social and Civic Participation in the United States. Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. http://wilsoncenter.org/invisible-no-more-background-papers.

- García Zamora, R., S. G. Olvera, and O. Pérez Veyna. 2018. “La diáspora mexicana en Estados Unidos y el Programa 3X1 como desarrollo comunitario transnacional: lecciones y desafíos.” In Desarrollo territorial y urbano, edited by José Luis Calva, 295–314. Mexico: Juan Pablos Editor and Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo.

- Garibay, C., A. Bony, F. Panico, and P. Urquijo. 2011. “Unequal Partners, Unequal Exchange: Goldcorp, the Mexican State, and Campesino Dispossession at the Peñasquito Goldmine.” Journal of Latin American Geography 10 (2): 153–176.

- Gil Olmos, J. 2016. “Los desplazados por la narcoviolencia.” Proceso 2111, October 12.

- Glick-Schiller, N., and T. Faist, eds. 2010. Migration, Development and Transnationalization: A Critical Stance. New York: Berghan Books.

- Golden, T. 1991. “The Dream of Land Dies Hard in Mexico.” New York Times, November 27.

- Goldring, L. 2002. “The Mexican State and Transmigrant Organizations: Negotiating the Boundaries of Membership and Participation.” Latin American Research Review 37 (3): 55–99.

- González-Barrera, A. 2015. More Mexicans Leaving than Coming to the U.S. Hispanic Trends. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2015/11/19/more-mexicans-leaving-than-coming-to-the-u-s/.

- Gordillo de Anda, G., and T. Plassot. 2017. “Migraciones internas: un análisis espacio-temporal del periodo 1970-2015.” Economía UNAM 14 (40): 67–100.

- Granados Alcantar, J. A., and M. F. Quezada Ramírez. 2018. “Tendencias de la migración interna de la población indígena en México, 1990-2015.” Estudios demográficos y urbanos 33 (2): 327–363.

- Haggblade, S., P. Hazell, and T. Reardon, eds. 2007. Transforming the Rural Nonfarm Economy: Opportunities and Threats in the Developing World. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

- Hall, J. 2011. Ten Years of Innovation in Remittances. Lessons Learned and Models for the Future. Washington, D.C.: Multilateral Investment Fund, Inter-American Development Bank.

- Hernández García, M. G. 2020. “El desplazamiento interno forzado: Un desgarramiento invisible en el campo mexicano.” La Jornada del Campo 150: 3. https://issuu.com/lajornadaonline/docs/delcampo150.

- Hernández-León, R. 2008. Metropolitan Migrants. The Migration of Urban Mexicans to the United States. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Hewitt de Alcántara, C., ed. 1994. Economic Restructuring and Rural Subsistence in Mexico: Corn and the Crisis of the 1980s. La Jolla, CA: Center for US-Mexican Studies/UN Research Institute for Social Development. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3v3166pn.

- Hirschman, A. 1970. Exit, Voice and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Organizations, Firms and States. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Hoogesteger, J., and F. Rivara. 2020. “The End of the Rural/Urban Divide? Migration, Proletarianization, Differentiation and Peasant Production in an Ejido, Central Mexico.” Journal of Agrarian Change. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/joac.12399.

- IDMC (International Displacement Monitoring Centre). 2020. Global Report on Internal Displacement. Geneva: International Displacement Monitoring Centre/Norwegian Refugee Council.

- INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática). 2010. Censo de Población y Vivienda 2010.

- Israel, E., and J. Batalova. 2020. Mexican Immigrants in the United States. Migration Information Source, November 5, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/mexican-immigrants-united-states-2019.