ABSTRACT

We utilize perspectives in environmental sociology and political economy to examine relationships between human exploitation and ecological degradation. Specifically, we apply global labor value chains and the tragedy of the commodity to analyze severe labor exploitation in Thai capture fisheries. Our analysis suggests that severe labor exploitation has played a significant role in lowering the market value of the Thai seafood sector as an adaptation to a competitive marketplace driven by increasing commodification and a stressed marine ecosystem. Regarding ecologies, we detail how the degradation of marine ecosystems in the region stimulated increased demand for severe labor exploitation.

Introduction and background

Seafood markets in the global North depend upon a highly complex and nebulous series of seafood commodity, or value, chains. In the modern capitalist world food system, capture fisheries and farmed fisheries (aquaculture) are global operations. Accordingly, increases in production and consumption of seafood products depend upon high levels of trade in global commodities, both farmed and captured, supplied by regional firms who operate in the waters and factories of the global South. These socio-structural conditions shape processes of production – including the labor process – and are ecologically significant.

Here, we develop an analysis of the interaction between labor processes, global political-economic dynamics, and changing ecological conditions in Thailand’s seafood sector. We emphasize concerns around severe exploitation of migrant fishers who work in Thailand. Our analysis of this case provides insights on the ongoing socio-ecological contradictions and tensions in the capitalist world food system, particularly in the seafood sector.

Thailand’s economy and, specifically, its agricultural sector have received special attention for prolific growth and productivity. Accordingly, the World Bank touts Thailand as one of the world’s ‘great development success stories’ (World Bank Citation2017). McMichael (Citation1993, Citation2012) refers to Thailand as a model NAC or ‘new agricultural country’ where the state has successfully promoted agro-industrialization for urban and export markets often centered in affluent nations, the core of the capitalist world-system. Thailand’s seafood sector plays an important part in this narrative of economic success.

On the other side of this developmental narrative lies a poorly kept secret. As numerous nongovernmental and international governmental organizations (NGO and IGO) and journalistic reports demonstrate – including the Environmental Justice Foundation, Human Rights Watch, the International Labour Organization, The New York Times, and The Guardian – Thai fisheries rely upon extremely exploitative labor practices to capture and process fish for sale in global markets (EJF Citation2015; HRW Citation2018; ILO Citation2013; Stoakes et al. Citation2014). Sometimes called ‘unfree labour,’ these practices use ‘coercion or compulsion to extract labour from workers … [and] often involves deception at the point of entry into work, as well as coercion that precludes workers from exiting labour relationships that are highly exploitative’ (LeBaron and Phillips Citation2019, 1). This is no small matter for the Thai economy, as the market value for seafood exports for Thailand reaches nearly $6 billion US and accounts for roughly 20 percent of Thai product exports (USDA Citation2018). This case is particularly important to consider in light of broader developments in the world food system. Indeed, exporting luxury or perceived high-quality seafood products is somewhat typical in the global seafood trade, where richer nations often import perceived high-quality fish protein from poorer nations (Asche et al. Citation2015).

Our aim is to provide needed structural, political economic and ecological, context to this social problem. As we clarify in the discussion section, our analysis indicates that the Thai seafood sector is ecologically and economically stressed, and that severe labor exploitation of impoverished migrants is a limited attempt to maintain market viability in a crowded, unequal, and global seafood industry. Prior to this analysis, we provide background on the issue of labor, particularly forms of severe exploitation including forced labor, in the Thai seafood sector. This background predominantly focuses on recent reforms and their effects, and illustrates the persistent nature of severe exploitation in the Thai seafood sector – especially in its capture fisheries, which now fish mostly for low-trophic level, so-called, ‘trash-fish.’ We then clarify our theoretical frameworks. This is followed by an analysis of changing economic and socioecological conditions in the Thai seafood sector and discussion of the findings and implications of this research.

Our analysis emphasizes the limitations of conceptualizing the material basis of seafood commodity chains as inherently low-value, especially in the empirical context that this case presents on fishing labor and marine ecosystems. We reason that the prioritization of capitalist exchange or market value results in false notions of labor in this sector as a low-value social process. In addition, we argue that systemic failures to recognize or appreciate the inherent worth of ecological utility and capacity for sustaining life – i.e. ecological wealth – are, similarly, products of a social system that prioritizes commodity exchange value. Thus, we reason that reforms and development strategies that attempt to sidestep such structural tensions by emphasizing efficiency gains, state management, and corporate social responsibility will encounter obstacles that stem from commodification, a central component in the social metabolic order of the capital system (Mészáros Citation2000).

Analytical approach

Our analytical framework is deductively arranged based on two critical theoretical frameworks in political economy and environmental sociological theory: global labor value chains (GLVC) and the tragedy of the commodity. We analyze pertinent data on economic valuation, trade, labor, and fisheries ecology from leading international organizations. These data are drawn primarily from the Harvard Atlas of Economic Complexity, an interactive software program that is publicly available and useful for building data visualizations according to economic sectors within nations. In this data set, economic valuation of fisheries products is at an aggregated scale. Thus, fisheries export value includes non-fish species, like shrimp, as well as seafood products that are processed or preserved. We also analyze fisheries production and export data taken from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, utilizing similarly aggregated fisheries data, as well as data on labor and fishing taken from the Thai Department of Fisheries and NGO sources, such as the International Labor Organization. For the purpose of this analysis, we utilize the broader phrase ‘seafood sector’ to include captured fish, reared aquaculture, and processed seafood commodities.

We develop our analysis section into two sub-sections that we organized around the theoretical frameworks. First, we highlight empirical data pertinent to commodification; particularly, changes in labor relations, fishing technology, and marine ecosystem stress. We chose to begin the analysis with this, as the industrialization and subsequent ecological intensification of the Thai seafood sector predates its contemporary political economic position in global labor value chains. This placement provides materialist, historical context that enables an effective understanding of the contemporary, socioecologically precarious state of the Thai seafood sector.

The data presented within our global labor value chain subsection primarily examines market valuation within the Thai seafood sector. In doing so, we emphasize that the valuation of Thai seafood sector products is a reflection of abstract exchange value, operationalized as price or market value. Thus, we consider these economic data in the context of severely exploited migrant fishing labor and increasingly degraded marine systems.

In the discussion section, we elucidate a socioecologically informed description of the political economic context under which severe exploitation, within the Thai seafood sector, occurs. While processing plant labor abuses are a concern within the seafood sector, our analysis chiefly considers the socio-structural and ecological drivers of deteriorating labor conditions at sea, in Thai capture fisheries. However, a sizeable portion (approximately 60 per cent) of this catch fuels aquaculture production as feed inputs (EJF Citation2015). Thus, our analysis necessarily includes discussions on the socioecological importance of aquaculture. Overall, our analytical approach follows the methodological principles of contemporary, historical materialist studies of environment and society (Holleman Citation2015). Thus, when considering value, we recognize the central importance of capitalist social relations of production in these determinations (Burkett Citation2005). Accordingly, our analysis engages social and ecological conditions through a critique of capital’s class relations. An analysis based off this supposition aims to uncover how exploitation and conflict are often hidden in data that, if not evaluated through a critical, historical materialist lens, may appear somewhat removed from the antagonistic class relations central to capital accumulation (Holleman Citation2015).

Background: labor exploitation in the Thai seafood sector

Between 2013 and 2015, a number of journalistic reports from major news outlets documented extremely troubling conditions suffered by migrant fishers in Thailand. While NGOs and IGOs had already been conducting studies on the matter (EJF Citation2015; ILO Citation2013; Solidarity Center Citation2009), media coverage brought international attention. Relatedly, as a result of ongoing discussions regarding illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing in Thai fisheries, in 2015 the European Union issued a (now lifted) ‘yellow card’ for the Kingdom of Thailand, which served as a final warning before a full ban on Thai seafood imports (White Citation2016). For its part, the United States downgraded Thailand to its lowest score on their Trafficking in Persons report (Reed Citation2018). Major food distributors like Costco, Walmart, and Tesco also reacted to brand pressure and bad press by investigating their supply chains further, providing more information to customers, and pressuring their major suppliers, such as Thai Union Group, to upgrade their chains (Gold, Trautrims, and Trodd Citation2015; Nakumura et al. Citation2018; Reed Citation2018).

In response, the Thai government, which took power through a military backed coup in 2014, enacted regulations that registered migrant workers, extended health care coverage, and made contracts (which included some worker protections, such as mandatory rest) a requirement (Vandergeest, Tran, and Marschke Citation2017). The Thai government also extended the minimum wage to fishers in 2014 (ILO Citation2018). Thai Union Group, whose officials expressed shock over the reports, also took steps to ensure control over its shrimp supply chain and voided all contracts with shrimp processors and vertically integrated their processing operations (Reed Citation2018).

However, a series of recent reports document persistent and new problems. Many workers still do not receive the minimum wage (ILO Citation2018; Issara Citation2017). According to Human Rights Watch (Citation2018), nearly 60% of interviews with escaped or current fishers reveal some degree of coerced labor. Other studies, such as Chantavich, Laodumrongchai, and Stringer (Citation2016), detail that violence against workers is common, and more likely suffered by Burmese workers who do not speak Thai. Abuse, maltreatment, and exploitation are typically found to be more severe in long-haul voyages – especially ones where transshipping occurs (Issara Citation2017). However, workers on long-haul voyages are often underrepresented in survey and interview research due to their extended time – sometimes years – out at sea.

State regulatory practices sometimes directly or indirectly facilitate conditions that result in extreme exploitation and ‘unfree labor’ (LeBaron and Phillips Citation2019). Indeed, new regulations – while often helpful – can lead to unintended consequences. The Issara Institute (Citation2017) documents how captains and net bosses control migrant fishers’ movements by restricting access to the fishers’ pink cards, which fishers need to avoid arrest and possible deportation. Other survey research confirms that migrant workers frequently lack access to at least one form of government identification (CSO Coalition Citation2018). Moreover, the ILO discovered a patterned increase in fees and pay reductions implemented by captains, many of which are arbitrary, thinly veiled attempts to recoup minimum wage earnings paid to migrant fishers (ILO Citation2013, Citation2018).

The persistence of these troubles points to potentially intractable contradictions endemic to the political economy of fisheries and seafood. Producers must compete in a global market, across stressed ecosystems, to create value (Campling, Havice, and Howard Citation2012). A fishery, as Campling, Havice, and Howard (Citation2012) notes, must compete both horizontally (across similar scale actors) and vertically, between capital and the environmental conditions in which the fishery operates. Accordingly, even so-called successful management programs often overlook or misunderstand labor and sociological dynamics within fisheries (Simmons and Stringer Citation2014; Song, Johnsen, and Morrison Citation2017).

This complexity allows Thai Union group, a company whose market value exceeds $1.5 billion US, to refer to illegal fishing and labor rights violations as ‘inherent risks’ within the seafood sector (Thai Union Group Citation2017, 68). Perhaps accordingly, the Thai seafood sector is still dependent upon exploited migrant labor to catch fish in spite of reforms. Today, the overwhelming majority of fishers in Thailand are working-age men who migrate from Myanmar (Burma) and Cambodia. The majority of these fishers report sending remittances home (70%, according to CSO Citation2018), and 98% express that the potential to send remittances drive their desire to work in fishing (Issara Citation2017). It is thus unsurprising that many cite a ‘deteriorating rural livelihood’ as motivation to migrate to find work at sea, in Thailand (Vandergeest Citation2019, 329).

While migrant labor is commonplace across the Thai seafood sector, an increasing amount of attention points toward the disturbing irony that a great deal of severely exploited fishing labor goes toward the capture of low-priced ‘trash-fish,’ a term used to characterize species deemed unfit for human consumption, which are instead often processed into cat food and aquaculture feed (EJF Citation2015, Citation2019; Fischman Citation2017). Much of this effort supports Thailand’s aquaculture industry, which requires trash fish inputs (ILO Citation2016).

Theoretical framework

Labor value commodity chains

Hopkins and Wallerstein (Citation1986, 159) initially formulated the concept of global commodity chains (GCC) to describe the geographically extensive ‘network of labor and production processes whose end result is a finished commodity.’ Social scientists advanced such conceptions to emphasize value. Sturgeon (Citation2008) notes the concept of value aligned better with the structure of the chain, across which actors engage in ‘value added’ procedures beyond the initial, most upstream node of ‘low value’ production.

Key global value chain (GVC) scholarship identifies the transnational corporation as the primary actor in the structuring and governance of value chains (Gereffi Citation2005). Gereffi (Citation1994) argues that GVCs are increasingly buyer (as opposed to producer) driven, and that this organizational dominance allows firms to establish value added nodes downstream, away from initial, upstream production sites. Value chains within the global food system are typically described as buyer driven, dominated by food distribution or grocery firms (e.g. Walmart, Tesco, Mars, etc.) centered in the global North, who can set prices and profit more from value added production (Burch and Lawrence Citation2009; Busch and Bain Citation2004; Pechlaner and Otero Citation2008).

Some researchers critique shortcomings of GVC scholarship, particularly, the tendency to de-historicize the role of capital in favor of meso-level firm studies and the acceptance of neoclassical market assumptions concerning value and valuation (Bair Citation2004; Bair and Werner Citation2011; Carr, Chen, and Tate Citation2000). As a consequence of these shortcomings, scholarship that probes issues of labor relations and class struggle tend to ‘occupy a marginal position’ in food studies (Marsden, Barbosa Cavalcanti, and Bonnano Citation2014: xiii). This theoretical relegation is evident in GVC literature, which often posits that export oriented industrialization failed to lift less-affluent nations out of poverty, not because of systemic labor exploitation and downstream value capture, but rather from failures to successfully engage in so-called economic upgrading. From this perspective, countries ‘can “climb the value chain” from basic assembly activities using low-cost and unskilled labor to more advanced forms,’ of production (Gereffi Citation2015, 18). Thus, production activity that requires higher degrees of technology, knowledge, and ‘skill’ (i.e. less labor intensive) are the mechanisms for creating value in the modern economy (Hernández et al. Citation2014).

The consequence of this marginalization extends beyond the scholarly realm. For example, a recent ILO (Citation2016) study of Thai seafood value chains does not assign a price to the inputs caught for shrimp farms, effectively suggesting that this contribution is worthless to the aggregate value accumulated throughout the chain. The most lucrative, high priced node of the shrimp supply chain is instead the distribution and retail component, where half of all Thai shrimp production ‘is sold and transported to international markets, mainly to big retailers’ (ILO Citation2016, 15). Here, the labor that went into feeding, growing, and harvesting the shrimp constitutes the least valuable portions of the shrimp value chain. While the ILO (Citation2016) does not disregard the procurement of feed for aquaculture entirely, it assumes that its material composition as a ‘low-value added species … unfit for human consumption,’ accounts for its minimal capacity to generate earnings within the chain.

Thus, we find it necessary to extend upon scholarship that is critical of neoclassical assumptions of economic valuation. Suwandi (Citation2019) emphasizes the ‘labor value commodity chain’ as the driving force behind the global labor arbitrage, or the effort of global North firms to engage in arms-length contracting to source productive, cost-efficient labor in the global South. As opposed to mainstream GVC theory, which commonly stresses technology, skill, and knowledge as the creators of value, in the global labor value chains approach, Suwandi (Citation2019) emphasizes productive relations, or the social processes that result in the material procurement of the commodity. These processes are dependent upon the living labor of vulnerable low paid workers, who toil in the factories, farms, and oceans of the global South. From this perspective, capitalistic exchange value reflects socio-historical conditions between people (Burkett Citation2014; Foster and Burkett Citation2018). Thus, attempts to explain some forms of labor as inherently low-value due to their level of skill, knowledge, technicality (etc.) risk obscuring social relations of production and reifying exchange value as a veritable indicator of a commodity’s usefulness or inherent worth (Burkett Citation2014).

The primary aim of globalization of production and consumption, from this perspective, is to appropriate as much value as possible from the labor process. Global North firms achieve this goal via the maintenance of low unit labor costs, which require a highly productive workforce with paltry wage compensation (Suwandi Citation2019). Unit labor costs remain low through the proliferation of the global labor arbitrage, essentially the worldwide ‘race to the bottom,’ where global South nations compete for global North capital investment via, in part, weak regulatory protections for labor that maintain low wages. Global North firms increasingly rely upon arms-length contracting, where they negotiate extremely profitable, non-equity relationships with global South producers (Suwandi Citation2019). This form of contracting characterizes the norm of buyer-driven commodity chains within the global agri-food system.

Because global labor value chains (GLVC) analysis centers on labor and the susceptibility of exploitation, it avoids common pitfalls endemic to NGO’s, media outlets,’ and journalistic sources’ conceptions of value and value production. These sources often make slavery, forced labor, and all forms of extreme exploitation seem outside the norm within a market system (Vandergeest and Marschke Citation2019). This not only results in shortsighted, top down policy prescriptions that ignore what workers want (Vandergeest Citation2019; Vandergeest, Tran, and Marschke Citation2017), but also risks overlooking the significance of labor exploitation for the accumulation of capital – regardless of whether or not fishers are paid a minimum wage. Because GLVC centers the focus of analysis on unit labor costs, we can better address such shortcomings. We thus use the inclusive term ‘severe exploitation’ to characterize migrant labor in Thai fisheries.

The GLVC perspective is also effective for avoiding reifying or uncritically interpreting data on economic development and valuation (Burkett Citation2014). For example, Smith (Citation2016) elucidates why scholars should not interpret gross domestic product (GDP) as the value procured from domestic production. Rather, GDP is a more accurate reflection of surplus value seized from production, a process that arms-length contracting helps to obfuscate (Smith Citation2016). Smith (Citation2016) demonstrates how the global labor arbitrage and false conflation of value with price leads to fallacious interpretations of trade relations and economic growth across unequal nations and firms.

As an example, if Thai seafood firms seek to attract global North buyers (which they certainly do), they must offer as competitive a price as possible to compete in a global market. This pressure has reverberating effects throughout the chain, but notably for the producers of material inputs (trash fish), who are also pressured to find ways to lower their sale price. As export-oriented Thai shrimp firms manage to cut production costs by slashing the prices paid to these fishers for their inputs, they attempt to maintain competitiveness as global North suppliers. However, the compensation returned to Thailand decreases in at least a relative fashion, as their unit value added must necessarily decline.

Nevertheless, from a neoclassical interpretation of export valuation, it would therefore appear that Thai shrimp production itself is a less economically valuable endeavor. Smith’s (Citation2016) writing on the global labor value chains thus forces us to ask an important question: how can the value of commodity production be inversely related to the sale and profits of the same commodity in global North markets? Similar to the above example on labor compensation, conceptions of the value chain as comprised of nodes within which value is added, often through increasingly skilled and specialized production processes, risk overlooking that pricing and the valuation process are enmeshed within social relations. Thus, much like the cost paid to purchase labor power, price paid to suppliers of commodities is indicative more of socio-political contestations than it is a concrete reflection of commodity value (Smith Citation2016). Therefore, price or market value typically fails to reflect the worth of the labor time or ecological wealth that the commodity represents.

The tragedy of the commodity

Environmental sociologists have forwarded the tragedy of the commodity approach in order to unpack the broad socioecological effects of capitalist fisheries production across the globe (Clark et al. Citation2018; Clark and Longo Citation2019; Longo, Clausen, and Clark Citation2015). From this perspective, capitalist commodity production, particularly at the material bases of food systems, necessitates intensified ecological withdrawals and production of waste in order to satisfy the demands of commodity production. Contrary to the well-known tragedy of the commons thesis, pressures on ecosystems stem from the social logic of capital, which demands the growth of abstract, limitless exchange value. The expansion of exchange value is therefore a pre-requisite of investment that tends to supersede human need or the regenerative requirements for ecosystem sustainability.

Under capitalist commodity production, exchange value ‘is the fundamental sign for producers with regard to what they should produce’ (Saito Citation2017, 109). As such, bio-physical conditions are frequently utilized in a manner that rationally accommodates the demands of an economic system governed by a quantitatively limitless, alienated value form. For example, this involves processes of biological speed up, where the life cycles of aquatic species are shortened in order to accelerate turn-around on investment (Longo, Clausen, and Clark Citation2014).

Longo, Clausen, and Clark (Citation2015) note that institutional responses to ecological disruption prefer to rely upon techno-solutions or geographic fixes in order to maintain the circuit of capital accumulation in the face of ecosystem degradation. Efficiency mechanisms or spatial shifts in extraction do not address the underlying antagonism between the regenerative demands of ecosystems and the limitless quest for exchange value expansion necessitated by generalized commodity production. Across the seafood sector, there exist multiple examples of such superficial ‘fixes’ to ecological degradation, including fishing for species with briefer life cycles, expanding into new marine frontier(s), and placing hopes in intensive aquaculture development (Longo et al. Citation2019; Pauly and Palomares Citation2005; Tickler et al. Citation2018).

The tragedy of the commodity perspective also emphasizes the inequitable distribution of socioecological tragedy across nations, identities, and classes (Clark Citation2020; Longo, Clausen, and Clark Citation2015). As labor value commodity chain theory suggests, capital accumulation in global fisheries favors the interests of global North firms and markets (Barbesgaard Citation2018; Hannigan Citation2017; McCall- Howard Citation2017). Uneven development across fisheries has involved massive shifts in labor systems and marine ecologies, towards socioecological relations more amenable to commodity production, and ultimately capital accumulation (Longo, Clausen, and Clark Citation2015; McCall- Howard Citation2017).

Inequitable structuring of global labor value chains across an unequal world system also tends to obscure the most deleterious ecosystemic effects of commodification. In short, modern labor value chains outsource more ecologically intensive forms of production into impoverished and less affluent nations (Clark and Longo Citation2019; Jorgenson Citation2005; Rice Citation2007; Roberts and Parks Citation2009). These regions’ ecologies are then subjected to the demands of commodity exchange in order to (primarily) benefit global North firms (Foster and Holleman Citation2014). Capital relates to complex ecologies (and the social utility, or wealth, they generate) in a one-sided manner, or ‘only insofar as they facilitate the production of (exchange) value’ (Foster and Clark Citation2020, 236).

Recent work (Frame Citation2019; Longo et al. Citation2019) characterizes the capitalist semi-periphery, or middle-income, economically ‘emergent’ nations as especially important as mediators in this expropriation of ecological wealth. These nations, in short, often possess the geographic proximity and techno-political capacity to exploit their peripheral neighbors in service of northward capital flows. Yet, because global North firms determine the market for the commodities procured from food producers, semi periphery firms and nations, such as the Thai seafood sector, remain subordinate to the governance and economic demands of core nations and core-centered firms (Gereffi Citation1994; Wang Citation2017).

Analysis

The tragedy of the commodity in Thai fisheries

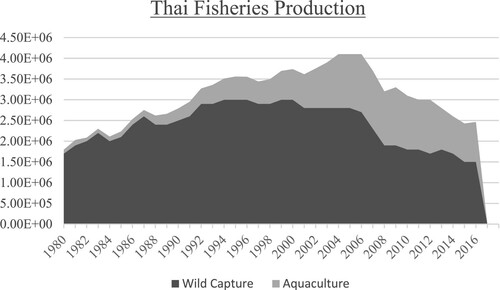

Decades before Thailand came to occupy its current position in the political economy of the global seafood system, its fisheries industrialized and shifted toward producing commodities for the capitalist world-market. In the 1960s, Thai fishing fleets began to rely increasingly upon trawling methods to capture fish. As such, Marr, Campleman, and Murdoch (Citation1976) described the Gulf of Thailand as overexploited, with future fishery growth dependent upon long-distant hauls (Marr, Campleman, and Murdoch Citation1976; Pauly Citation1979). In the 1980s, following a period of national development, Thailand transitioned to an export-oriented and specialty food-commodity producing nation. This transition was fueled by capital investment from global North nations, which stimulated intensified intra-regional corporate investment supported by a cooperative Thai state (Onuki Citation2008). By 1980, Japanese and U.S. backed capital accounted for about half of total capital investment, and much of this was focused in the agricultural sector, in conjunction with structural adjustment programs (Goss and Pacheco Citation1999). Foreign capital investment in more technically intensive forms of production fostered vertical integration in key seafood sectors, as well as contract farming, which characterized the agro-modernist turn in Thailand during this time (Goss and Burch Citation2001). As illustrates, this period of investment and global commodification corresponded with the intensified industrialization of the Thai fleet, and a decline of smaller scale fishing methods.

Table 1. Thai fishing methods (SEAFDEC) and developmental investment flows (FAO).

Over the same period of time, the social organization of Thai fisheries changed drastically as well. In , artisanal fishing implies that fishers catch all or a majority of their haul with the intent of selling it to market, whereas subsistence fisheries utilize their catch for barter, domestic consumption, and rely on two or fewer employees (Teh, Zeller, and Pauly Citation2015). As demonstrates, subsistence yields decreased by nearly 50% over a 30-year period, while market-oriented production and industrial fishing both increased substantially. Also, during this time, small scale shrimp farmers became more dependent upon regional, transnational firms for extension services and financial support, which effectively fostered dependence on capital intensive, transnational corporations (Goss, Skladany, and Middendorf Citation2001; Onuki Citation2008).

Table 2. Thai fishery yields grouped by sector (measured in tons).

There are two telling indicators of the ecological effects of commodification in Thai fisheries over these decades. One, increased technological efficiency (marked by development of more intensive production methods) did not correspond with a leveling off of ecological withdrawal. A common, neoclassical assumption in fisheries development is that modernization and marketization of the economy and increased technological efficiency will effectively meet consumer demand, ideally with less ecological impact. As a general example, the FAO (Citation2015) emphasizes efficiency more than 20 times in a 28-page report on blue growth, placing it as a central component of increased sustainable development in multiple arenas of the seafood sector. Yet, Thai fisheries exhausted significantly more effort to maintain and expand catch rates in spite of more efficient technological capacity and increased commodification. According to a survey of its cumulative fishing effort over several decades, the Thai Department of Fisheries found that their catch per unit effort declined by nearly 90% between 1960 and 1990, and has reached historic lows in more recent years (Thai DoF Citation2015).

confirms the present reality of decades of intensive fishing, both within and beyond Thailand’s immediate waters, as it displays the extent to which Thai fisheries exceeded maximum sustainable yield rates and so-called optimal efforts. Notably, only catch efforts for anchovies caught in the Andaman Sea remained under the ‘optimal fishing effort,’ measured in days (Thai DoF Citation2015). Optimal level of fishing effort quantifies the amount of time needed to reach the maximum sustainable yield, given the technical capacity of the Thai fishing fleet. The FAO (Citation2019) defines maximum sustainable yield as the highest theoretical level of harvest that can be extracted from a wild-fish population without potentially affecting the population’s viability in future years. Regardless of the ecological validity of these concepts, which have been challenged, surpassing the optimal level of fishing effort suggests that the Thai fishing fleet has been engaged in greater amounts of time and energy to capture particular yield levels and thus continues to surpass already stressed bioecological boundaries.

Table 3. Maximum sustainable yield and effort in Thai fisheries (Thai DoF Citation2015).

To maintain fisheries export production in this struggling marine ecological system, Thai fisheries have also relied upon increased aquaculture effort (). Despite the fact that aquaculture production methods can be quite effective at producing massive amounts of seafood, evidence suggests that it does not likely offset the fishing impacts of wild-caught, capture fisheries (Longo et al. Citation2019). This is further demonstrated in Thailand’s growing rate of capture of small feed fish, whose flesh and oil are often processed into feed for aquaculture farms. In contemporary industrial Thai fishing, roughly 60 percent of fishery captures in the Gulf of Thailand consist of so-called ‘trash-fish,’ or low-trophic level fish with a variety of uses, such as fish feed in aquaculture (EJF Citation2015).

This shift in the emphasis of Thai fishery catch has noteworthy implications. As Pauly et al. (Citation1998) explain, the tendency to fish at lower trophic levels indicates a pattern of unsustainable fishing where smaller, lower trophic species come to replace catches of larger, piscivorous fish, as they become scarce. Not only does this phenomenon imply overfishing, but increased fishing at low trophic levels has particular, reverberating impacts on marine biodiversity and ecology (Smith et al. Citation2011). Pauly and Chuenpagdee (Citation2003) confirm that, over a period of 20 years (1977–1997), the mean trophic level of catches in Thai fisheries declined rapidly, and thus ‘profoundly modified the ecosystem’ of the Gulf of Thailand (347).

Finally, Thai fisheries have utilized their regional political economic power to exploit fishery resources beyond their own waters. This effort constitutes a geo-spatial fix to the ecological effects of global commodification. After the creation of marine EEZ’s, Thailand continued to fish in Burmese, Indonesian, and other nearby and neighboring nations’ waters either illegally or with negotiated permission – often because nations’ with less industrialized fishing fleets used the EEZ’s as a bargaining chip for other, non-fishing related matters (Butcher Citation2004). Marine scientists note that, when adjusting for catches beyond the EEZ of Thailand, rates of Thai fishery captures triple (Derrick et al. Citation2017).

Thus, increasing commodification in Thai fisheries was a significant driver of historic overfishing in Southeast Asian waters. After decades of intensive and expansive fishing practices, the region is, ecologically speaking, a shell of its former self. Over 60 percent of Southeast Asian fisheries’ resource is estimated to be at medium to high risk of overfishing – and risk is higher in the waters of poorer nations, such as Cambodia (DeRidder and Nindang Citation2018). When including waters of the Andaman Sea, catch per unit effort declined 86 percent since the late 1960s (EJF Citation2015).

Understanding Thailand’s position in global labor value chains

In 1993, the World Bank announced that they considered Thailand a high performing Asian economy – indeed, a central component of their ‘East Asian Miracle’ report (World Bank Citation1993). This report came at the zenith of a decade long period of significant economic growth rates. That growth followed the Thai government’s relaxation of non-tariff trade barriers (and other mechanisms) designed to stimulate export-oriented development (Bumgarner and Prime Citation2001). Following the Asian Financial Crisis in the mid 1990s, Thailand continued to grow rather strongly through the millennium and is, according to some recent assessments, turning a corner and moving out from a recent and short-lived economic malaise (World Bank Citation2018).

However, Thailand’s prospects for continued economic expansion, beyond a middle income or semi-periphery nation, appear uncertain. As an emergent economy, Thailand is a victim of its own success. Foreign capital investors increasingly consider Thailand at a disadvantage, caught in the tellingly named ‘middle income trap,’ for the simple reason that cheaper labor is obtainable in poorer and more firmly peripheral states (Nikomborirak Citation2017). Put differently, Thailand’s ‘middle income trap’ suggests that it is caught between ‘the competitive edge of low wages among developing countries and the high value-added market of more developed countries,’ and that this positionality serves to limit economic growth and capital investment (Tipayalai Citation2020, 2). This quagmire has resulted in Thai economists calling for a fourth stage of development known as ‘Thailand 4.0’ that emphasizes the promotion of a value-based economy, fueled by biotech, the promotion of ‘knowledge intensive’ industries, and the creation of export processing zones (Louangrath Citation2017; Royal Thai Embassy).

The implications behind Thailand’s ‘middle income trap’ must be understood. Thai labor costs are, in the manufacturing sector, relatively expensive for the region (Wharton School of Business Citation2017). Indeed, they more than doubled in a ten-year period in spite of growth in unit labor productivity, or output per unit of time worked, of the workforce (). From the standpoint of capital, this rising unit labor cost suggests that the Thai economy is trending in a less competitive and less profitable direction.

Table 4. Thailand Labor Data, Manufacturing Sector (Adapted from Jin Citation2017).

The steadily rising unit labor cost for domestic, Thai workers within the manufacturing sector in part explains what scholars refer to as a persistent labor shortage in Thai fisheries (Fischman Citation2017). Extant research on Thai capture fisheries reveals that Thai nationals make up a paltry percentage, between 0 and 9%, of Thai fishing vessels and also occupy more well-paid positions like captain or net-boss (CSO Citation2018; HRW 2018; Issara Citation2017). However, such positions of authority on board fishing vessels are few. Low paid migrants from Cambodia and Myanmar perform most of the work on Thai fishing vessels. This steady reserve of replaceable, impoverished workers from poorer states deflates the price for labor within Thai fisheries. While this influx of migrant labor surely reduces unit labor costs in Thai fisheries, it does little to attract domestic workers who can make better wages in manufacturing or other sectors.

Furthermore, the structure of the buyer-driven, agri-food labor value chain reduces the political power of vulnerable workers in the seafood sector. If labor activists, states, or organizations raise awareness of severe fisher exploitation at the base of supply chains, the buying-firm may simply relocate their supply to chains with weaker oversight, where similar problems either do not exist or, more pessimistically, have yet to be exposed (Cartensen and McGrath Citation2012). Labor scholarship also emphasizes the difficulty in organizing agricultural workers in agri-food commodity chains due to, for example, geographic and social isolation of agricultural workers (Ford Citation2015), and such difficulties are all the more apparent in the seafood sector.

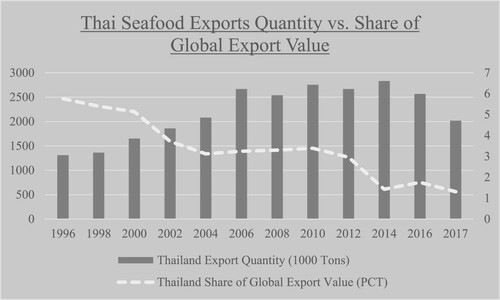

These socio-structural forces help the migrant-dependent, Thai seafood sector in efforts to sidestep the ‘middle income trap’ that the Thai manufacturing sector occupies. However, the Thai seafood sector’s reliance on severely exploited, migrant labor has not resulted in improved prosperity within the global seafood supply chain. Rather, it appears to be a tactic of economic survival. (FAO Food Balance Citation2020; Harvard Growth Lab Citation2020) displays how, over time, Thailand’s share of global, seafood sector export value has consistently declined. also details how this rate of decrease in the share of global export value declined in spite of increases in quantity of seafood exported, up and until the most recent years for which data is available. This suggests that Thai fisheries products have been devalued, or cheapened, in recent decades.

Figure 2. Fish exports vs. share of global seafood sector value (FAO Food Balance Data Citation2020; Harvard Growth Lab Citation2020).

Indeed, confirms that Thai fisheries exports have lost unit value over time. Again, in spite of an overall growth in gross exports of seafood products, Thailand’s net export valuation deteriorated substantially. Thus, the decline of Thai seafood export value is not simply the result of other fisheries capturing more of the market – Thai seafood commodities are becoming less economically valuable, from a market perspective. Moreover, Thai gains in seafood sector productivity (as indicated by export production rates) were not able to offset this loss of market value. The value per ton of Thai seafood exports decreased measurably during this time period. Overall, in ten years, the value of Thai seafood exports declined by nearly 350% per ton. This decline has occurred in spite of the fact that Thailand is re-orienting much of its seafood sector to incorporate so-called value added production of re-export commodities and technical processing (USDA Citation2018).

Table 5. Seafood export quantity and valuation over time, Thailand (Harvard growth lab, FAO Food Balance Data Citation2020).

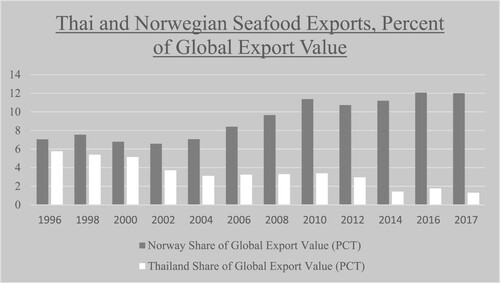

The global marketplace for seafood products also constrains Thai seafood sector development. Over the last two decades, European seafood sectors of comparable size to Thailand have successfully promoted their own high-priced seafood, like farmed salmon. Notably, salmon also comprises a substantial portion of Thai Union Group’s aquaculture effort (Thai Union Group Citation2017). Yet, (Harvard Growth Lab) demonstrates how Norway – Europe’s largest seafood exporter – has followed a radically different path in its seafood sector development.

Figure 3. Comparison of Seafood Sector Valuation, Share of Global Export Value, Norway vs. Thailand (Harvard Growth Lab Citation2020)

While Norway has an exceptionally lucrative seafood sector, other export-oriented European seafood sectors bear similar trends. Spanish seafood exports, for example, captured nearly double the level of economic valuation in 2017 of Thai seafood, despite being less productive in terms of quantity of seafood exported.

Thailand must also, increasingly, compete with so-called developing nations’ seafood sectors across Asia. Over the last two decades, China, India, Vietnam, and Indonesia have ramped up their seafood export production, and have overtaken Thailand in terms of economic value procured from seafood exports. The following three figures (Harvard Growth Lab Citation2020), display how drastically the market for Asian seafood exports has shifted over the last two decades. Asian nations such as China, India, and Vietnam have flooded the global seafood market with massive amounts of seafood production, both farmed and captured ().

Figure 4. (A) Treemap of seafood export valuation for Asian Nations. Share of global value, 1996. (B) Treemap of seafood export valuation for Asian Nations, share of global value, 2006. (C) Treemap of seafood export valuation for Asian Nations, share of global value, 2016.

Thus, Thai seafood exports are both less valuable, from a neoclassical perspective on value chains, and less competitive in a crowded market, where many nations in the region engage in high-volume export-oriented production of similar commodities, at similarly low prices. In this context, it is necessary to consider the increased reliance on severe exploitation of migrant workers in Thai capture fisheries. Severe exploitation helps to maintain the economic viability of Thai seafood, but in a highly limited, inequitable, and unsustainable fashion.

Discussion

This case connects parallel, critical approaches on globalization and development with environmental sociology and critical studies of commodification and ecology. Through the application of these perspectives, we collected and analyzed relevant data on economic valuation, work and labor, and fisheries ecology to assess the socioecological conditions under which severely exploited, migrant labor came to be a ‘management practice’ for much of the Thai seafood sector (Crane Citation2013).

First, we explain how GLVC can be enriched by engaging this perspective with the socioecological concerns emphasized by the tragedy of the commodity. Chiefly, GLVC analyses have focused on the manufacturing and textiles sectors. Applying the labor theory of value to the global commodity chain, Smith (Citation2016) and Suwandi (Citation2019) reinvigorate commodity chain research by emphasizing labor exploitation and value capture as the driving impetuses behind economic globalization. While this work has thus far been limited in its application toward labor and valuation in food systems, we argue that it is quite useful for understanding why the cost of agri-food system labor is systematically devalued and how this is closely linked to ecological conditions.

When one considers the metabolic obstacles to capital accumulation that the agri-food system poses, the pressure to engage in severe exploitation of the labor force becomes more apparent. Generalized commodity production is dependent upon the ongoing turnover of the capital circuit. Value, formed in production, must be realized through continuing processes of distribution and consumption (Marx Citation1985). The nature of capital accumulation thus suggests that firms must constantly work to reduce time and costs associated with production and circulation, or risk disrupting the required turnover of capital needed to keep the circuit moving in a manner conducive to accumulation (Mann and Dickinson Citation1978; Smith Citation2016).

Commodified fisheries require intensified forms of production that trend away from methods that are more in line with the naturally existing metabolic flows of marine-based ecologies. From the standpoint of capital, ecological systems become inefficient if they cannot fuel the capital circuit quickly enough. Also, global commodification in fisheries tends to undermine smaller scale and less-intensive fishing approaches. Unlike a technological- and capital-intensive fishing fleet, these methods are unable to engage in geographically expansive voyages or trawl the depths of the ocean floor. Intensive methods become all the more necessary as ecosystems are degraded, because declining ecological fecundity typically requires increased investment in fixed capital to overcome physiological limits presented by stressed ecosystems (Bunker and Ciccantell Citation2005). These socioecological realities makes cutting costs for labor all the more important for capital accumulation.

Some INGO’s have linked over-fishing to exploitative labor conditions in Thai fisheries (e.g. EJF Citation2015; Oxfam Citation2014). Yet, these studies and reviews often do not associate over-fishing with capital accumulation processes and the structure of an inequitable, commodified world food system. Further, explanations for sustained over-fishing typically grant agency to technology itself. In the Oxfam (Citation2014) report, for example, such problems are said to be driven by ‘a rapidly expanding fishing fleet,’ bolstered by ‘destructive fishing gear,’ which led to a ‘Malthusian extraction of marine resources’ (Oxfam 2014, 42).

From this perspective, these are essentially outcomes of the tragedy of the commons, where human nature, interacting with enough technological capacity, will invariably degrade marine systems beyond recognition. The consequences of overlooking capital’s social metabolic relations are also evident when the EJF (Citation2015) argues that the Thai seafood sector has over-valued trash fish and failed to recognize the economic potential of fishery conservation. As is evident in Thai fishery valuation data, the problem is not that Thai fishery commodities are over-valued. This view also suggests that improved management of the fleet is ‘the best route to maximizing revenue capture’ (EJF Citation2015). While better management and regulation might improve some indicators, as the tragedy of the commodity approach suggests, such methods tend to run counter to the immediate, self-valorizing logic of capital. Moreover, improved nation-state level regulation would do little to address unsustainable practices in other locations, especially in the waters of the global South, where retailers can continue to seek untapped and less-regulated markets to purchase seafood.

Conditions specific to Thailand interact in important ways with these structural dynamics. For example, Thailand’s historical trajectory of commodification and integration with the capitalist world market exceed key, emergent rivals, such as Vietnam, whose contemporary seafood producers are still relatively small scale with less access to capital intensive inputs and technologies (Pham, Huang, and Chuang Citation2014; Tran et al. Citation2013). Also, relative to the region and emergent inter-regional competitors like Vietnam, Thailand’s fishery sector is characterized by highly commodified, arms-length contracting, where smaller scale fishers and fish farmers possess weak bargaining power in relation to the buyers of their products (ILO Citation2016). This setting – which also exacerbates traceability difficulties – is made economically feasible via Thailand’s close proximity to and relationships with comparatively poorer nations, whose rural reserve labor army supplies Thailand with its fishers. In short, geo-political conditions specific to Thai fisheries and the structural imperatives of a capitalist world food system interact to foster a dynamic that is rife for severe exploitation.

As we note, Thailand’s responses to reports of forced labor are not insignificant at the firm or state level. Yet, problems of labor abuses and severe exploitation persist because, even in a more regulated context, the structural pressures of commodification bear down on actors working within the system. Thus, in spite of a ‘B’ response from the Global Slavery Index, Thailand still rates roughly 7 points higher than the regional average on the index’s vulnerability score, a measure of slavery risk (Global Slavery Index Citation2016). This stems in part from Thailand’s geo-spatial fix to its overextended marine ecosystem, which has included subsidies to support long-haul voyages needed to catch increasingly scarce fish (Global Slavery Index 2020). These long-haul voyages are difficult to regulate, and widely known to contain higher risk for labor abuse.

As the tragedy of the commodity presents, states and international organizations have preferred techno-solutions to serious reforms that challenge the demands of capital accumulation. In large part to meet structural demands and contend with ecological change, intensive aquaculture production has been characterized as a potential win-win, where species can be reared in controlled environments, and fed supplements sourced from low-trophic and ‘inedible’ fish. This practice, though, has altered the metabolic structure of marine systems, and induced mass biological speed-up. In this case, fishing down food webs represents an attempt to overcome the metabolic obstacles of marine systems that tend to impede the turnover of capital. In these examples, the dominance of the logic of commodity exchange – to utilize ecological systems in a manner more amenable to the expansion of exchange value – is apparent, and clearly alters the stability of marine socioecological systems.

Indeed, efficiency – under a logic of on-going commodification and capital accumulation – does not strike a balance with ecosystems. These fisheries often come up against the biological limits in marine systems and the metabolic demands of fish species, caught or farmed. Capital accumulation in the fisheries sector (and elsewhere in the world capitalist food system) is thus more directly subjected to the limitations of metabolic cycles of nature than in many other sectors. Furthermore, in spite of the increased technological capacities of an industrial fleet and capital-intensive aquaculture, seafood production remains extremely dependent upon human labor. Aquaculture farming may be more controlled and economically efficient, but it is not dematerialized, and indeed requires massive amounts of labor-intensive inputs, typically from other capture fisheries that increasingly focus on catching trash-fish. Thus, the capitalist seafood sector is not only costly – it is one that is fundamentally difficult to automate. These socioecological circumstances contribute to producing the conditions for severe exploitation of labor in fisheries, particularly in fisheries like those in Thailand, which have been extensively commodified.

To be sure, Thailand faces serious challenges to remain competitive in a crowded global seafood sector. Its ‘middle-income trap,’ characterized by rising unit labor costs in its growing manufacturing sector, helps to generate a domestic labor shortage within an industry whose labor costs must be systematically reduced to an extreme degree. Thus, in the Thai seafood sector, efforts to remain competitive have been associated with importing its seafood labor-force from the poorer, and more firmly peripheral states it borders. This reliance on severe exploitation points to the geo-political significance of semi-periphery nations in global labor value chains, particularly in the buyer-driven global food system. Expansive and extra-legal fishing measures that exploit nearby, more firmly peripheral workers and the marine ecosystem are required in order to maintain some degree of economic viability in a highly competitive labor value chain where global North retailers and distributors can control the price of commodities, set the market, and push risk and competition upstream.

This relation also points to the limits of dominant development paradigms and narratives of modernization that emanate from mainstream INGOs. . Indeed, sustaining the viability of Thai fisheries within the context of the world capitalist food system and ecological decline demands a steady supply of impoverished workers from poorer regions of periphery nations. Thailand, and the global North firms it supplies with low-cost seafood, thus have an underlying economic interest in maintaining the social conditions that characterize severe migrant labor exploitation in fisheries. This reality suggests that NGO reports that characterize the Thai state’s mismanagement of its fisheries as the primary driver of the persistence of forced labor may shift the focus away from corporate buyers in the global North, who continue to plead ignorance about what goes on at the most upstream nodes of their supply chains.

Finally, as we demonstrated, the devaluation of Thai fish products via the reliance on severe exploitation has not led to relative prosperity for the Thai seafood sector. This case sheds light on how unsustainable development occurs over time in an important geographic center of the world food system. Severe labor exploitation has enabled a precarious industry to survive and extract relatively meager levels of economic value in the context of a highly competitive global seafood market, one in which more and more of the value is captured by firms in the global North. Thus, we reason, the biggest ‘winners’ of Thailand’s political-economic position are the global North firms and retailers who have benefited from the buyer-driven, global labor arbitrage that has pushed competition upstream, towards producers in the global South.

Conclusion

This study advances theory in the political economy of globalization and the environment and provides socioecological context to a social problem, from a critical, structural perspective. We advance the theory of the global labor value chain by applying it to a case of severe labor exploitation in an important sector of the world capitalist food system, seafood production. Labor in agri-food systems is, too often, naturalized as being unskilled, undesirable, and of low value. Such connotations are also apparent with descriptions of ‘trash-fish’ as nearly economically worthless. This reification of capitalist valuation obscures the exploitation that fuels profits emanating from global South fishery operations, as well as in other sectors of the labor-dependent agri-food system. In a world market dictated by global North firms (buyers), producers must compete to offer relatively inexpensive products to distributors who serve these buyers.

Rather, in this case we demonstrate that declining rates of market valuation indicate value capture from Thai fisheries. This points to Thailand’s precarious political economic position in the global seafood commodity chain. The Thai seafood sector must compete, i.e. reduce production costs, against other firms across different nations that can offer similar commodities to global North markets. However, the Thai seafood sector must maintain its foothold in global seafood commodity chains within an increasingly stressed marine ecological system. As the tragedy of the commodity perspective suggests, severe labor exploitation amounts to a fairly limited management approach – the underlying antagonisms between capital, labor, and ecology remain, which work to undercut the potential of future fishery development in the region.

Furthermore, this case study should be useful for future analyses of seafood value chains and unequal ecological exchange across the world food system. For example, future studies can explore the extent to which seafood supply chain managers reify conceptions of value, and thereby naturalize labor exploitation in seafood supply chains. Because firms govern and manage their supply chains, and because seafood supply chains are difficult to regulate, some argue that the solution to forced labor at upstream nodes of production must come from firm governance strategies or corporate social responsibility (Busch and Bain Citation2004; Gereffi and Lee Citation2016; Seafood Slavery Risk Tool Citation2018). This has resulted in a nascent industry of seafood ethics and supply chain risk consulting. However, corporate social responsibility risks naturalizing trends in neoliberal re-regulation where states have, with intentionality, often relinquished responsibility for enforcing labor and environmental regulations (LeBaron and Phillips Citation2019). Further, continued monopolization and financialization prioritize short term profit for shareholders whose interests and concerns limit effective, voluntary action taken by multi-national firms (LeBaron Citation2020). Future research on corporate social responsibility should keep these considerations in mind.

It is also crucial that further work recognize another important matter that this case highlights: the global dynamic of environmental injustice as it pertains to unsustainable development. The extraction of natural resources and the destruction of ecological wealth typically benefit firms in the global North, and thus reinforce a globalized system of white, capitalist hegemony (Holleman Citation2018; Pellow Citation2007). It is impossible to ignore the social reality that firms in the global North, dominated by mostly white men, and affluent nations in the world-system enjoy and profit from the ‘luxury’ or ‘specialty’ commodities caught and processed by impoverished, brown-skinned fishers, in many cases working against their will and in brutal conditions, in the global South.

In this case study, we examined the combined and interacting tragedies of severe exploitation and marine degradation that are socially driven to a significant degree by global commodity systems. We suggest that severe exploitation will continue to be a major concern in global fisheries as long as the commodification of seafood intensifies and is the primary mechanism by which food is produced and distributed. Thus, the de-commodification of food becomes a central means for addressing concerns associated with social equity and ecological sustainability.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Timothy P. Clark

Timothy P. Clark is a PhD Candidate (spring 2021 graduation) at North Carolina State University (USA) in the Sociology Department. His research examines the socioecological dynamics of food systems from a political economic-ecological perspective. His work has direct implications for labor relations, structural obstacles to sustainable development, and the social drivers of ecological degradation. Clark's scholarship has received recent publication in Journal of Rural Studies, International Journal of Comparative Sociology and other outlets.

Stefano B. Longo

Stefano B. Longo is an Associate Professor of Sociology at North Carolina State University, USA and currently a Visiting Researcher in Climate and Environment, at Lund University, Sweden. His research examines the relationships between social and ecological systems, with an emphasis on marine ecosystems, political economy, and food systems. Longo’s research has been published in a variety of journals such as Conservation Biology, Social Problems, and Social Forces, among many others. He is author of The Tragedy of the Commodity published by Rutgers University Press, co-authored with Rebecca Clausen and Brett Clark.

References

- Asche, Frank, Marc F. Bellemare, Cathy Roheim, Martin D. Smith, and Sigbjorn Tveteras. 2015. “Fair Enough? Food Security and the International Trade of Seafood.” World Development 67: 151–160. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.10.013.

- Bair, Jennifer. 2004. “From Commodity Chains to Value Chains and Back Again?” https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/0614/fd881bf4f02d7b9a224c82f9a0f9ca92d2d1.pdf?_ga=2.231139291.534066418.1593030668-849764121.1589482503.

- Bair, Jennifer, and Marion Werner. 2011. “Commodity Chains and the Uneven Geographies of Global Capitalism: A Disarticulation Perspective.” Environment and Planning 43: 988–997.

- Barbesgaard, Mads. 2018. “Blue Growth: Savior or Ocean Grabbing?” The Journal of Peasant Studies 45 (1): 130–149. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2017.1377186.

- Bumgarner, Mary, and Penelope B. Prime. 2001. “The East Asian Miracle? Thailand Melts Down.” International Institute of Business. Georgia State University. http://scholarworks.gsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1033&context=intlbus_facpub.

- Bunker, Stephen, and Paul Ciccantell. 2005. Globalization and the Race for Resources. Baltimore, Maryland: JHU Press.

- Burch, D., and G. Lawrence. 2009. Supermarkets and Agri-Food Supply Chains. Transformations in the Production and Consumption of Foods. Cheltenham: Edward Elger.

- Burkett, Paul. 2005. Marxism and Ecological Economics: Toward a Red and Green Political Economy. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

- Burkett, Paul. 2014. Marx and Nature. A Red and Green Perspective. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

- Busch, Lawrence, and Carmen Bain. 2004. “New! Improved? The Transformation of the Global Agrifood System.” Rural Sociology 69 (3): 321–346. doi:https://doi.org/10.1526/0036011041730527.

- Butcher, John G. 2004. The Closing of the Frontier: A History of the Marine Fisheries of Southeast Asia, c. 1850-2000. Pasir Panjang, Singapore: ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute.

- Campling, Liam, Elizabeth Havice, and Penny McCall Howard. 2012. “The Political Economy of Capture Fisheries: Market Dynamics, Resource Access and Relations of Exploitation and Resistance.” Journal of Agrarian Change 12 (2): 177–203.

- Carr, Marilyn, Martha Alter Chen, and Jane Tate. 2000. “Globalization and Home-Based Workers.” Feminist Economics 6 (3): 123–142.

- Cartensen, Lisa, and Siobhan McGrath. 2012. “The National Pact to Eradicate Slave Labour in Brazil: A Useful Tool for Unions.” Global Labour Column 117.

- Chantavich, Supand, Smarn Laodumrongchai, and Christina Stringer. 2016. “Under the Shadow: Forced Labour among Sea Fishers in Thailand.” Marine Policy 68: 1–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2015.12.015.

- Clark, Timothy P. 2020. “Mining the Sea: A Within-Case Comparative Analysis of the Atlantic Menhaden Fishery in the Age of Capital.” Sociology of Development 6 (2): 222–249.

- Clark, Timothy P., and Stefano B. Longo. 2019. “Examining the Effect of Economic Development, Region, and Time Period on the Fisheries Footprints of Nations (1961-2010).” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 60 (4): 225–248. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0020715219869976.

- Clark, Timothy P., Stefano B. Longo, Brett Clark, and Andrew K. Jorgenson. 2018. “Socio-Structural Drivers, Fisheries Footprints, and Seafood Consumption: A Comparative International Study, 1961-2012.” Journal of Rural Studies 57: 140–146. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.12.008.

- Crane, Andrew. 2013. “Modern Slavery as a Management Practice: Exploring the Conditions and Capabilities for Human Exploitation.” Academy of Management Review 38 (1): 49–69. https://journals.aom.org/doi/abs/https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2011.0145.

- CSO Coalition for Ethical and Sustainable Seafood. 2018. “Falling Through the Net.” http://ghre.org/downloads/Falling-through-the-net_en-version.pdf.

- DeRidder, Kim J., and Santi Nindang. 2018. “Southeast Asia’s Fisheries Near Collapse from Overfishing.” The Asia Foundation. https://asiafoundation.org/2018/03/28/southeast-asias-fisheries-near-collapse-overfishing/.

- Derrick, Brittany, Pavarot Noranarttragoon, Lydia Dirk Zeller, C. L. Teh, and Daniel Pauly. 2017. “Thailand’s Missing Marine Fisheries Catch (1950-2014).” Frontiers in Marine Science 4: 402. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2017.00402.

- Environmental Justice Foundation. 2015. “Thailand’s Seafood Slaves. Human Trafficking, Slavery, and Murder in Kantang’s Fishing Industry.” file:///C:/Users/chassco/Desktop/dissertation%20stuff/labor%20in%20fishing/EJF-Thailand-Seafood%202015.pdf.

- Environmental Justice Foundation. 2019. “Blood and Water. Human Rights Abuse in the Global Seafood Industry.” https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Blood-water-06-2019-final.pdf.

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). 2015. “Achieving Blue Growth Through the Implementation of the Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries.” http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/newsroom/docs/BlueGrowth_LR.pdf.

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). 2019. Glossary. http://www.fao.org/3/y3427e/y3427e0c.htm.

- Fischman, Katharine. 2017. “Adrift in the Sea: The Impact of the Business Supply Chain Transparency on Trafficking and Slavery Act of 2015 on Forced Labor in the Thai Fishing Industry.” Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies 24 (1): 227–252.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2020. Food Balance Data. http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/FBS.

- Ford, Michele. 2015. “Trade Unions, Forced Labour, and Human Trafficking.” Anti Trafficking Review 5: 11–29.

- Foster, John B. and Brett Clark. 2020. The Robbery of Nature. Capitalism and the Ecological Rift. New York: Monthly Review Press.

- Foster, John B. and Paul Burkett. 2018. “Value Isn't Everything.” Monthly Review 70 (6): 1–17.

- Foster, John Bellamy, and Hannah Holleman. 2014. “The Theory of Unequal Ecological Exchange: A Marx-Odum Dialectic.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 41 (2): 199–233. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2014.889687.

- Frame, Mariko. 2019. “The Role of the Semi-Periphery in Ecologically Unequal Exchange: A Case Study of Land Investments in Cambodia.” In Ecologically Unequal Exchange, edited by R. Scott Frey, Paul K. Gellert, and Harry F. Dahms, 75–106. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gereffi, Gary. 1994. “The Organization of Buyer-Driven Commodity Chains: How U.S. Retailers Shape Overseas Production.” In Commodity Chains and Global Capitalism, edited by Gary Gereffi, and Miguel Korzeniewicz, 95–122. Westport, CT: Praeger.

- Gereffi, Gary. 2005. “The Global Economy: Organization, Governance, and Development.” The Handbook of Economic Sociology 2: 160–182.

- Gereffi, Gary. 2015. “Global Value Chains, Development, and Emerging Economies.” United Nations Industrial Development Report. Working Paper Series.

- Gereffi, Gary, and Joonkoo Lee. 2016. “Economic and Social Upgrading in Global Value Chains and Industrial Clusters: Why Governance Matters.” Journal of Business Ethics 133 (1): 25–38. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2721292.

- Global Slavery Index. 2016. “The Global Slavery Index 2016.”

- Gold, Stefan, Alexander Trautrims, and Zoe Trodd. 2015. “Modern Slavery Challenges to Supply Chain Management.” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 20 (5): 485–494.

- Goss, Jasper, and David Burch. 2001. “From Agricultural Modernization to Agri-Food Globalization: The Waning of National Development in Thailand.” Third World Quarterly 22 (6): 969–986.

- Goss, Jasper, and David Pacheco. 1999. “Comparative Globalization and the State in Costa Rica and Thailand.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 29 (4): 516–535.

- Goss, Jasper, Mike Skladany, and Gerad Middendorf. 2001. “Dialogue: Shrimp Aquaculture in Thailand: A Response to Vandergeest, Flaherty, and Miller.” Rural Sociology 66 (3): 451–460.

- Hannigan, John. 2017. “Toward a Sociology of Oceans.” Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue Canadienne de Sociologie 54 (1): 8–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/cars.12136.

- Harvard Growth Lab. 2020. Atlas of Economic Complexity. https://atlas.cid.harvard.edu/explore?country=undefined&product=102&year=2004&productClass=HS&target=Product&partner=undefined&startYear=1995.

- Hernández, René, Jorge Mario Martínez Piva, and Nanno Mulder. 2014. Global Value Chains and World Trade: Prospects and Challenges for Latin America. Santiago, Chile: United Nations Publication.

- Holleman, Hannah. 2015. “Method in Ecological Marxism. Science and the Struggle for Change.” Monthly Review 67 (5): 1–10.

- Holleman, Hannah. 2018. Dust Bowls of Empire: Imperialism, Environmental Politics, and the Injustice of Green Capitalism. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Hopkins, Terrance, and Immanuel Wallerstein. 1986. “Commodity Chains in the World Economy Prior to 1800.” Review: A Journal of the Fernand Braudel Center 10 (1): 157–170.

- Human Rights Watch (HRW). 2018. “Hidden Chains. Rights Abuses and Forced Labor in Thailand’s Fishing Industry.” https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/01/23/hidden-chains/rights-abuses-and-forced-labor-thailands-fishing-industry.

- ILO (International Labor Organization). 2013. Caught at Sea: Forced Labour and Trafficking in Fisheries. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labor Organization.

- ILO (International Labor Organization). 2018. Baseline Research Findings on Fishers and Seafood Workers in Thailand. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—asia/—ro-bangkok/—sro-bangkok/documents/publication/wcms_619727.pdf.

- ILO (International Labour Organization). 2016. “Global Supply Chains: Insights into the Thai Seafood Sector.” file:///C:/Users/tpclark2/Downloads/Global%20supply%20chains-%20Insights%20into%20the%20Thai%20seafood%20sector.pdf.

- Issara Institute. 2017. “Not in the Same Boat. Focus on Labour Issues in the Fishing Industry.” Issara Institute and International Justice Mission Report.

- Jin, Luyi. 2017. FDI and Manufacturing Industry in Asia. Lingnan Journal of Banking, Finance, and Economics. http://commons.ln.edu.hk/ljbfe/vol6/iss1/5

- Jorgenson, Andrew K. 2005. “Unpacking International Power and the Ecological Footprints of Nations: A Quantitative Cross-National Study.” Sociological Perspectives 48 (3): 383–402. doi:https://doi.org/10.1525/sop.2005.48.3.383.

- LeBaron, Genevieve. 2020. Combatting Modern Slavery: Why Labour Governance is Failing and What We Can Do about It. Cambridge, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

- LeBaron, Genevieve, and Nicola Phillips. 2019. “States and the Political Economy of Unfree Labour.” New Political Economy 24 (1): 1–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2017.1420642.

- Longo, Stefano B., Brett Clark, Richard York, and Andrew K. Jorgenson. 2019. “Aquaculture and the Displacement of Fisheries Captures.” Conservation Biology 33 (4): 832–841. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13295.

- Longo, Stefano B., Rebecca Clausen, and Brett Clark. 2014. “Capitalism and the Commodification of Salmon: From Wild Fish to Genetically Modified Species.” Monthly Review 66 (7): 35–55.

- Longo, Stefano B., Rebecca Clausen, and Brett Clark. 2015. The Tragedy of the Commodity. New Brunswick: Rutgers Press.

- Louangrath, Paul. 2017. “Thailand 4.0 Readiness.” University of Technology International Conference, doi:https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.23190.86089.

- Mann, Susan A., and James M. Dickinson. 1978. “Obstacles to the Development of a Capitalist Agriculture.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 5 (4): 466–481.

- Marr, J. C., G. Campleman, and W. R. Murdoch. 1976. “An Analysis of the Present and Recommendations for the Future Development and Management Policies, Programmes, and Institutional Arrangements, Kingdom of Thailand.” FAO/UNDP South China Sea Fisheries Development and Coordinating Programme, Manilla, SCS/76.

- Marsden, Terry, Josefa Salete Barbosa Cavalcanti, and Alessandro Bonnano, eds. 2014. Labor Relatiosn in Globalized Food. Bingley, UK: Emerald Publishing Group.

- Marx, Karl. 1985. Capital Volume 2. The Process of Circulation of Capital. New York City: New World Books.

- McCall- Howard, Penny. 2017. Environment, Labour, and Capitalism at Sea: Working the Ground in Scotland. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

- McMichael, Phillip. 1993. “World Food System Restructuring Under a GATT Regime.” Political Geography 12 (3): 198–214. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0962-6298(93)90053-A.

- McMichael, Phillip. 2012. Development and Social Change: A Global Perspective. Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

- Mészáros, István. 2000. Beyond Capital: Toward a Theory of Transition. New York: Montly Review Press.

- Nakumura, Katrina, Lori Bishop, Trevor Ward, Ganapathiraj Pramod, Dominic Chakra Thomson, Patima Tungpuchayakul, and Sompong Srakaew. 2018. “Seeing Slavery in Seafood Supply Chains.” Science Advances 4: e1701833.

- Nikomborirak, Deunden. 2017. “Thailand’s Barren Agriculture and Services Industries Key to Growth.” East Asia Forum. https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2017/07/18/thailands-barren-agriculture-and-services-industries-key-to-growth/.

- Onuki, Hironori. 2008. The Political Economy of Globalizing Food in World Politics: Global Agro-Food System and Its Discontent in Shrimp Aquaculture. Toronto, Canada: York Centre for Asian Research.

- Oxfam. 2014. “Final Report. Mapping Shrimp Feed Supply Chain in Songkhla Province to Facilitate Feed Dialogue.” Sarinee Achavanuntakul, Lead Researcher.

- Pauly, Daniel. 1979. “Theory and Management of Tropical Multispecies Stocks. A Review, with Emphasis on the Southeast Asian Demersal Fisheries.” https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/54e1/7e83a34973908faf02646c0ff281495cf5c4.pdf.

- Pauly, Daniel, and Ratana Chuenpagdee. 2003. “Development of Fisheries in the Gulf of Thailand Large Marine Ecosystem: Analysis of an Unplanned Experiment.” In Large Marine Ecosystems of the World: Change and Sustainability, 337–354. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/a336/c79b7e9b297ae3de0e8d6650b0cad8c7bb50.pdf.

- Pauly, Daniel, Villy Christensen, Johanne Dalsgaard, Rainer Froese, and Francisco Torres. 1998. “Fishing Down Marine Food Webs.” Science 279 (5352): 860–863. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.279.5352.860.

- Pauly, Daniel, and Maria-Lourdes Palomares. 2005. “Fishing Down Marine Food Web: It Is far More Pervasive than We Thought.” Bulletin of Marine Science 76 (2): 197–212.

- Pechlaner, Gabriela, and Gerardo Otero. 2008. “The Third Food Regime: Neoliberal Globalism and Agricultural Biotechnology in North America.” Sociologia Ruralis 48 (4): 351–371. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9523.2008.00469.x

- Pellow, David N. 2007. Resisting Global Toxics. Transnational Movements for Environmental Justice. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Pham, Thi Duy Thanh, Hsiang-Wen Huang, and Ching-Ta Chuang. 2014. “Finding a Balance between Economic Performance and Capacity Efficiency for Sustainable Fisheries: Case of the Da Nang Gillnet Fishery, Vietnam.” Marine Policy 44: 287–294.

- Reed, John. 2018. “Thai Union: Cleaning up an Abusive Supply Chain.” Financial Times. Accessed May 2020 via Proquest.

- Rice, James. 2007. “Ecological Unequal Exchange: International Trade and Uneven Utilization of Environmental Space in the World System.” Social Forces 85: 1369–1392. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2007.0054.