ABSTRACT

This article explores the relationship between the uneven outcomes of development in Indonesian cities with exclusionary outcomes of capitalist development in rural areas. Combining concepts of planetary urbanization with critical agrarian studies, we show how sociospatial and socionatural differentiations in (post-) New Order Java result in the emergence of the Kaum Miskin Kota, a ‘stagnant relative surplus population’ residing in precarious flood-prone urban spaces. These forms of differentiation are dialectically related to rural enclosures caused by the creation of political forest and political water. Tracing such relations forms a good basis to connect rural- and urban-based social movements.

1. Connecting unevenness in the city with that in the country

Jakarta is marked by thousands of dense, iconic urban neighbourhoods situated alongside and sometimes on top of its rivers and canal banks. For more than a century, these neighbourhoods have provided the cheap and accessible places of possibility for those who migrate to the city from the countryside (Abeyasekere Citation1989; Bachriadi and Lucas Citation2001; Kusno Citation2013; van Voorst Citation2015; Prathiwi Citation2019). Many migrants have settled here due to the loss of land or other livelihood resources in their rural homes. Cities may offer them an alternative space for experimentation and improvisation (Simone Citation2014). Yet, urban livelihoods are typically precarious, not least because the land on which new migrants make their homes is frequently exposed to floods; constantly under threat of eviction; or targeted for improvement by a city government labelling them as ‘dirty settlements’ (pemukiman kumuh).

The precariousness of living alongside canals and rivers in Jakarta has increased over the past two decades (Goh Citation2019a). Flood events have become ever more frequent (Padawangi and Douglass Citation2015), triggering state-led flood management interventions geared at the removal of low-income settlements. These settlements are blamed by authorities of narrowing the waterways along or on top of which they are built, and of reducing the water retention and drainage capacity of the city as a whole. Critical analyses show how this technocratic framing depoliticizes as it draws attention away from the effects of upstream land use conversions and real-estate development in green urban areas by political and economic elites (Texier Citation2008; Rukmana Citation2015). Yet, grassroots activists who have generated and mobilized critical analyses in their struggles against evictions have so far had limited success in changing policies or public opinion.

Indeed, forced removals as justified by the exigencies of flood management seem to become increasingly accepted. This is why it becomes pertinent for activists and activist-scholars to look for and experiment with new political strategies to challenge prevailing diagnoses of and remedies to flood problems. In-line with alternative imaginaries of urban resilience (Goh Citation2019b), one promising proposition here is to better link urban marginalization to what happens in the countryside. By tracing how the rural drivers of displacement caused urbanization, it becomes possible to show how conflicts over urban land – historically associated with political demands for housing rights and rights to the city – are intimately and dialectically connected with rural land-based and environmental struggles. Activists’ hope is that making such linkages more visible will help mobilize and energize broader political support in a way more attentive to the dialectical nature of capitalist exploitation and dispossession.

The recent struggle against the state-induced closure of the Jakarta Bay in 2016 (Batubara, Kooy, and Zwarteveen Citation2018) provides a concrete expression of this strategy. In this nationwide campaign against the redevelopment of Jakarta’s coastline under the auspices of flood protection, urban poor grassroots organizations formed a coalition with agrarian movements to contest the plan’s eviction of urban poor settlements, as well as its exclusion of fisherfolk and other rural poor from access to the sea or land based resources. The first and second authors of this article were involved in this campaign through reviewing and writing reports for NGOs (Bakker, Kishimoto, and Nooy Citation2017; Sopaheluwakan et al. Citation2017). The initiative has so far been successful in slowing down land reclamation and preventing the closing of the Bay. It has also done a good job in contributing to make the city’s flood management plans a prominent topic of public debate (Savirani and Aspinall Citation2018). For Jakarta’s urban poor grassroots network, the coalition is expanding the existing city based issues to networks at the national, regional, and even global levels. Conversely, connecting urban struggles for housing rights with agrarian movements against land and resources grabbing offers the promise of re-building support for Indonesia’s peasant movements, many of which were decimated because of more than thirty years of the New Order regime (White Citation2015), the self-titled authoritarian regime (1965–1998) in Indonesia led by General Suharto which steered the violent restoration of a pro-capitalist order (the New Order) after the nationalist socialist democracy of prior decades (Farid Citation2005; Larasati Citation2013). The New Order Indonesia is a capitalist state (Hiariej Citation2003; see Sangadji Citation2021 for a more loose conception of ‘state and capital’) in which the state has the right to the majority of land and to issue large-scale land concessions. It is a ‘concessionary capitalism’ (Batubara and Rachman, Citationunder review).

This paper stems from our interest and participation in these ongoing conversations and forms of activism. We have come to realize that the ambition to link urban and rural struggles is a recurring one in discussions that happen in the circle of Indonesia’s urban and agrarian activists. Our exposure to and involvement in those conversations forms an important background, inspiration, and motivation for writing this article. We are enticed by the proposal to see urban and rural struggles as connected, requiring a collective strategy to question and ask for alternatives to forms of development that are uneven and exploitative. The paper, therefore, aims to create a firmer conceptualization of the relationship between what happens in cities with what happens in the countryside. It does this by exploring and substantiating how the uneven outcomes of development in cities (with those most at risk from floods and evictions belonging to low-income neighbourhoods) are linked to processes of differentiation in the countryside (with schemes to intensify agriculture or conserve forests benefitting some at the expense of many). We argue that cities and countryside are not just subject to similar processes of uneven capitalist development, but that they are also dialectically related to each other.

Our analysis is done from a concern with the fate of those living in flood-prone areas in Jakarta. This means that rather than providing new insights into processes and mechanisms of differentiation in the countryside, we aspire to contribute to explanations of the precarity of those living in Jakarta’s flood-prone areas. We do this by bringing insights from critical urbanization studies such as present in the edited volume by Brenner (Citation2014) into conversation with rural and ‘peasant’ focused critical agrarian studies (Peluso and Vandergeest Citation2020; Aditjondro Citation1998). We analyze urbanization as a specific (post-) New Order manifestation of state capitalism that works to leave large segments of the population in an extremely vulnerable position because they are without means of production and without access to formal employment.

We discuss our theoretical reflections against empirical evidence from Indonesia, focusing specifically on Java. Part of this empirical knowledge comes from over a decade of working with urban grassroots coalitions contesting evictions in Jakarta and agrarian social movements fighting for land right.

2. Connecting the city with the countryside: insights from urbanization studies and critical agrarian studies

The importance of strengthening the connections between the politics of the city and those of countryside has been repeatedly stressed by both critical urbanization scholars (Merrifield Citation2013; Goonewardena Citation2014; Ghosh and Meer Citation2020) and those critically studying agrarian differentiation such as the first editorial of Agrarian South: Journal of Political Economy (AS Citation2012). Both sets of scholarship make a similar plea: to look beyond the city as a spatial or ontological unit to theorize processes of urbanization, or to explain what happens in the city by referring to what happens in the countryside. Urbanization and agrarian scholars do this with a similar aim: generating a critical, action-oriented research agenda to contest the uneven outcomes of capitalist development. One central theme in both bodies of scholarship is a critical interrogation of the ways in which the urban – rural binary and related spatial demarcations separating the city from countryside seem natural or self-evident.

Breaking with this bias, critical urbanization scholars have, for example, pointed to the distinctly capitalist nature of urbanization, showing how the very demarcation between urban and rural is set in motion – and thus the effect of – a spatial concentration of the means of production and labour power in cities to help optimize the extraction of surplus (Marx Citation[1867] 1982, 772–781). Agrarian scholars have similarly bridged the divide by appreciating how both spaces are produced by and connected through processes of uneven capitalist development. Both Kautsky (Citation[1899] 1988) and Engels (Citation[1970] 1976) asked how to transcend the divide between urban labourers and rural peasants, a question that continues to figure with some prominence on the agenda of the contemporary transnational agrarian movement (Borras, Edelman, and Kay Citation2008, 170). AS (Citation2012, 9) underscores how, in today’s era of monopoly finance capital, Kautsky's and Engels’ proposals to connect urban exploitation with the eviction of peasant populations from the countryside remain urgently relevant. Although this relationship is amply theorized, agrarian studies and peasant studies in particular, have also been critiqued for having a bias toward the ‘peasant producer’ as political category in rural-based struggles and as analytical category around which social differentiation and resistance is operationalized (Jansen Citation2014).

Within critical urbanization theory, the question of how to articulate and politically mobilize the relations between the city and the countryside is particularly prominent in the thesis of planetary urbanization (PU) proposed by Neil Brenner (Citation2014). Anchored in Lefebvre’s (Citation[1970] 2014, 36) hypothesis that ‘society has been completely urbanized’, Brenner (Citation2014) calls for a re-theorization of the urban. PU proposes destabilizing the narrow conception of the urban as the spatial unit of the city by theorizing the processes through which cities – but also other spaces far outside and beyond (tar fields, pit mines, deforested lands) – are produced.

PU (Brenner Citation2014, 21) mobilizes the term ‘extended urbanization’ to refer to how the city needs to ‘extend’ to the countryside to continue functioning. Tracing how space, nature and society are transformed in the function of capitalism, Brenner and Schmid’s (Citation2014, 731; republished in Brenner Citation2014) PU thesis takes issue with the ‘urban age thesis’ of critical urban scholarship, as for instance reflected in Mike Davis’ (Citation2006, 1) Planet of Slums. Their critique is that this scholarship tends to accept the urban-rural divide through statements such as: ‘the urban population of the earth will outnumber the rural’. This is reflecting and reproducing a ‘methodological cityism’ (Angelo and Wachsmuth Citation2015, first published 2014 and republished in Brenner Citation2014), that over-focuses on assumed spatially-bounded city to the analytical neglect of processes of urbanization. Brenner and colleagues (in Brenner Citation2014) maintain that the analysis of processes of urbanization should be done at the scale of the planet to draw attention to the connectedness and similarities between the forms of globalizing capitalism that produce urbanization.

For our aim – i.e. connecting urban and rural social movements in Indonesia – it is more useful to ground the analysis in the particularities and specificities of urbanization in Indonesia, without forgetting how Indonesian processes of urbanization are part of, shaped by and connected to global flows of capital. In thinking through our theoretical-methodological approach, we were inspired by the rejoinders to PU (Peake et al. Citation2018) which emphasize how any analytical engagement with urbanization is necessarily rooted in specific experiences and part of specific political agendas. These scholars warn against attempts (such as Brenner’s) to theorize ‘the global urban’ from an un-identified position, because it risks perpetuating a colonial or imperial gaze that implicitly takes the own (often European) urban experience as the reference and norm (McLean Citation2018; Reddy Citation2018). We, therefore, insist on firmly anchoring our analysis of urbanization in the specific Indonesian experience. We follow Peake’s et al. (Citation2018, 380) suggestion to develop a ‘dialectical theory of urbanization’, going back and forth between the empirical and the theoretical, as well as between the city and the country, in appreciation of how ‘elements, things, structures and systems do not exist outside of or prior to the processes, flows, and relations that create, sustain or undermine them’ (Harvey Citation1996, 48–56). This means we consider cities and the countryside, as well as the overall system to which they belong, as appearing in a certain form because of the processes and relations through which they are constituted.

Our attempt builds on a long Indonesian tradition of activist-scholar alliances within rural political ecology and agrarian studies that have produced insightful analyses of how capitalist development has transformed space, society and nature in rural areas. We draw inspiration from Nancy Lee Peluso’s seminal work on the ‘political forest’, where she shows how the state’s spatial demarcation of land as forest in need of public protection and conservation that served to rationalize the dispossession of millions of people (Peluso and Vandergeest Citation2001; Vandergeest and Peluso Citation2006a) has increased dramatically under the New Order regime (Peluso Citation2011). George Junus Aditjondro analysed dam development as another important and parallel state-led process which deeply altered the countryside. Dam development for hydropower and agricultural intensificiation created what could perhaps be called ‘political water’ in analogy with Peluso’s ‘political forest’, as it also required mass evictions of local populations (Aditjondro Citation1993, Citation1998).

In the last decades in Indonesia, forest conservation and agricultural intensification together were the cause of processes of social differentiation, as well as of dispossession and impoverishment in the countryside. Several analyses have documented how the resulting disconnection of a large section of the population from their sources of livelihood and means of production (Habibi and Juliawan Citation2018) produced a flux of rural-to-urban migration (White Citation1977; Hugo Citation1982; Azuma Citation2000; Bachriadi and Lucas Citation2001; Breman and Wiradi Citation2004). Those migrating were transformed into what Marx (Citation[1867] 1982, 781–794) called ‘relative surplus population (RSP)’: people that are in surplus of industrial needs. This forces them into a situation of continuous precarity, with many of them working in the so-called informal sector. Ghosh and Meer (Citation2020, 12–13) refer to the ‘surplus population’ caused by agrarian differentiation as the ‘labour dimension’ of extended urbanization.

Being precise about who the surplus population are and where they come from is important, which is why there is indeed merit in replacing the oft-used term ‘informal economy’ (Bhalla Citation2017, 295) with Marx’s RSP. Marx said that there are four types of RSP: floating, latent, stagnant and pauperism (Marx Citation[1867] 1982, 794–802; well-systemized by Habibi and Juliawan Citation2018). Workers in the usually ‘unregistered, untaxed and generally unregulated’ informal economy belong to Marx’s stagnant RSP (Habibi and Juliawan Citation2018, 4), with the characteristics of an ‘active labour army, but with extremely irregular employment’ (Marx Citation[1867] 1982, 796; quoted in Habibi and Juliawan Citation2018, 4). Lane (Citation2010, 185 and 188) identified these people as Kaum Miskin Kota (KMK, urban poor), the ‘nonindustrial proletariat’, as important constituents of the movement that overthrew Suharto in 1998. A large part of this population are documented as moving to the city because of rural land dispossession (Habibi and Juliawan Citation2018, 15–16).

We mobilize Angelo and Wachsmuth’s (Citation2015, 19) identification of two dialectically-interconnected processes of urbanization, sociospatial and the socionatural differentiation, to structure our analysis. The former, the ‘in and beyond-city sociospatial reconfiguration’ or the ‘Lefebvreian moment’, is concerned with how capitalism re-organizes space in uneven ways. The latter refers to the entanglement of society and nature, highlighting how both are (re-)produced under capitalism. Specifically distinguishing socionatural processes of urban differentiation is useful as it draws attention to how urbanization transforms and often erodes or exhausts ecological functions. In our analysis, we emphasize how the sociospatial reconfigurations (the aforementioned political forests and political waters) and socionatural transformations (soil depletion, erosion, changes in water flows) in rural areas can be linked to the sociospatial reconfigurations (the expansion of the city) and socionatural transformations (increased proneness to floods and responses to this) characterizing the city. True to dialectical tradition, our choice for focusing on these processes and relations instead of others is importantly informed by their potential to energize new political alliances between the city and the countryside.

3. Methodology: reconstructing and tracing urban marginalization to the countryside

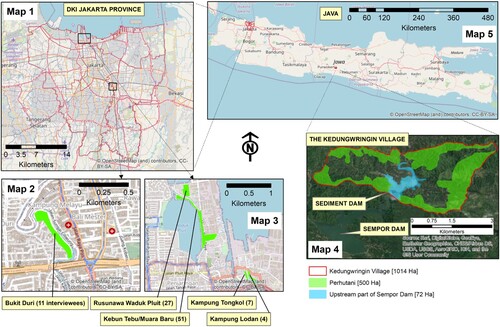

The first author complemented the knowledge gained through his involvement with social movements by multiple episodes of fieldwork conducted between 2016 and 2017. In 2016, five months (February–April and July–September 2016) were spent in Bukit Duri, one of KMK’s settlements in Jakarta. The other half of 2016 was also spent in Jakarta, but outside of Bukit Duri. In 2017, 3 months (September–November 2017) of fieldwork was conducted in the Kedungwringin Village, the District of Kebumen, Central Java Province, around 400 km far away from the capital Jakarta (, Map 1 and 5).

To begin with, in 2016 we engaged with Jakarta’s KMK through 100 interviews with residents in five neighbourhoods who were either threatened with eviction (Kampung Lodan, Jalan Tongkol, Kampung Tebu) or had already been evicted (Bukit Duri and Waduk Pluit) due to the planning and development of flood infrastructures (, Map 2 and 3). All interviewees were members and networks of the grassroots collectives of the Urban Poor Consortium or the Urban Poor Network (UPC/JRMK), both contesting the eviction. Our engagement with Jakarta’s KMK was helped by and based on the prior involvement of the first author since 2004 and of the last author since 2002 with UPC. The objectives of the conducted interviews were to understand the origin of KMK: why do they live there, where do they come from, and what kind of job(s) they do. We were also interested in knowing whether they (still) owned land in their place of origin, if indeed they came from somewhere else. While the sample was not statistically representative of the entire Jakarta’s KMK, we combined our primary evidence with the analysis of secondary sources documenting the processes through which capitalist development in Indonesia has unfolded, and their impact on rural land rights and village lives, particularly under the period of (post-) New Order Indonesia (1965–1998 and 1998–now). Doing this allowed us to see that what our interviewees told confirms what Indonesian urban migration scholars using much larger sample sizes have concluded about rural-born people in Jakarta (Papanek Citation1975; Temple Citation1975; Hugo Citation1982; Azuma Citation2000).

To link urban living and experiences to what happened in the countryside, we then interrogated our interview database to identify to what place of origin we could go, to further examine the drivers of migration to the city. Insight into the respondents’ backgrounds led us to conduct a second data collection in one of the identified places of origin: Kedungwringin Village. In Kedungwringin Village, the first author did participatory observations and interviewed 30 adults. We traced the historical dynamics of both political forest and political water by interviewing the state-owned forest company’s officers from the village-level up to its district and regional offices in the city of Purworejo and Salatiga; the municipality water company (PDAM) officer in the city of Kebumen; and the dam engineer in the town of Gombong. All four cities are located in Central Java Province.

In Kedungwringing, in addition to formally interviewing 30 adult villagers, the first author spent his daily life together with the Kedungwringin villagers (tapping Pinus trees, planting cassava, fixing broken water pipes, participating in or simply attending regular neighborhood/hamlet meetings in the night, attending wedding ceremonies, etc.). The story of one of the former Kedungwringin residents, Ibu Siji (pseudonym) is used to organize and empirically anchor the dialectical urbanization of the KMK urban dwellers. Her migration history is emblematic and resonates with the spikes in urbanization in the era between 1970 and 1990 under the New Order regime (Kompas Citation1977, Citation1992). Previous engagement of the first author with the ‘art for the people movement’ – part of the ‘forerunner of “participatory action research”’ (White Citation2015, 9; see, Kusni Citation2005) – defending farmers’ land rights against army occupation in Kebumen District (Mariana and Batubara Citation2015) helped situate Ibu Siji’s experience in wider processes of agrarian differentiation and movement dynamics. In linking the various experiences of rural and urban people, we also drew on numerous rich studies of agrarian differentiation in rural Java. This alerted us to the particular importance of the role of state (Hart Citation1988) in providing both the ‘context’ (claim over forest and modernization of irrigation infrastructure) and the ‘process’ (land dispossession) (White Citation1989, 25–26) of Indonesia’s ‘extended urbanization’.

4. Sociospatial reconfigurations under/through New Order

Ibu Siji decided to move to the city in 1980 following the negative impact of processes of sociospatial reconfiguration in her rural home village Kedungwringin on her economic opportunities. First she moved to the city of Bandung, in West Java, where she stayed for less than a year, working mostly in the informal sector. She then moved to the capital Jakarta, where more opportunities were available. Renting a room in the low income settlement near Waduk Pluit (a reservoir for water retention), she met her husband. Together, they worked in the informal sector, producing and selling food. They made enough money to buy their own room along the banks of Waduk Pluit. Following the eviction of the Waduk Pluit settlement in 2013, they moved to and now live in a nearby Rusunawa (a simple rental apartment) Waduk Pluit. Like Ibu Siji, the majority of the respondents of our survey (83) were not born in Jakarta, with 76 of them coming from rural villages. Only 3 of our interviewees can be classified as ‘formal economy’ workers, the rest are working in the ‘informal economy’.

In Ibu Siji’s village of Kedungwringing, the 2016 census categorizes around 49% (356 out of 726) of farming households as landless (KW Citation2016). This is a high percentage when compared to for instance the 7 villages in the 1970s Central Java recapitulated in Hart (Citation1978, 93), in which the percentages of villagers without cultivable land were 40, 34, 43, 22, 10, 39 and 17%. Ibu Siji’s family, as well as many of the 355 other villagers, lost their lands through two processes of sociospatial reconfiguration: the appropriation of village forests, and the construction of a large dam by the state. As for the first, almost half of what used to be village land (1104 hectares) in Kedungwringin is now owned by the state company Perhutani (500 hectares). This forest land was appropriated by the state for purposes of timber production and forest protection and conservation (, Map 4).

This process of turning village land into forest exemplifies what Peluso and Vandergeest (Citation2001) have termed political forest: the enclosure of forest lands by the state. As Peluso (Citation1988, xvii) notes, ‘village enclaves in the teak forest are among the poorest of the poor forest villages’. Political forest then explains the relatively high percentage of landless people in Kedungwringin. Ibu Siji’s village was far from exceptional. According to the company profile, Perhutani currently controls almost 2.5 million hectares of land (Perhutani Citation2019, 2) across 6381 villages (Diantoro Citation2011, 22) in the island of Java and Madura. With the enactment of the Basic Forestry Act 5/1967, the New Order regime claimed the majority of the country’s land as state forest (see, Peluso Citation2011; Li Citation2001; Ascher Citation1998; Barr Citation1998). From 1967 onwards, the New Order state extended its ‘political forest’ to the forested lands on Indonesia’s outer islands that had so far remained untouched (Vandergeest and Peluso Citation2006a, Citation2006b; Barr Citation1998; Gellert Citation2003), dividing forest lands into several categories (Siscawati Citation2014), including that of ‘industrial forest’. By 2018, 63% of Indonesia’s land area was demarcated as kawasan hutan or forest area (MEF Citation2018, 7). The Basic Forestry Act 5/1967 also made it possible for the New Order regime to allocate large-scale logging concessionaries to non-state companies, paving the way for massive capital investments in the logging sector (Peluso Citation2011; Li Citation2001; Ascher Citation1998; Barr Citation1998). Between 1967 and 1980, 519 logging concessionaires covering a total area of 53 million hectares were given to non-state corporations (Barr Citation1998, 6). One of these corporations was owned by Bob Hasan, Suharto’s close friend, who became a prominent figure in Indonesia's timber sector. In 1970, Suharto recommended Hasan as the local partner for the USA-based giant timber company, Georgia Pacific. In 1976, Hasan established the Indonesian Wood Panel Association (APKINDO), essentially a cartel of 13 companies. In 1994, at the heyday of the New Order regime, this cartel controlled at least seven million cubic metres of wood, 57% of the then world total tropical woods (Barr Citation1998; Gellert Citation2003).

The opening up of forest lands for capitalist investment and appropriation was accompanied by the active discouragement of other users and uses of the land, often by rendering those illegal. Villagers who previously lived in and from forest areas, often accessing and using these lands as commons, were now forcefully forbidden from continuing to do so. The New Order regime disqualified customary claims to land and forests, as these – by being anchored in attachments to specific places – stood in the way of the exchange and trade of land that was deemed necessary for realizing the state’s ambitions of control and profit-making (Vandergeest and Peluso Citation2006a; Peluso Citation2011).

In the village of Kedungwringin, the process of dispossession caused by commercial forestry was extended and deepened through the active promotion of more intensive and industrial forms of agriculture. From 1972 to 1978, under the national programme of agricultural modernization and irrigation associated with Green Revolution policies, the state funded the construction of the Sempor Dam to provide irrigation water for 6485 ha of farmland surrounding the village (DPU Citation1993). Through this, another 72 ha of land was claimed by the state, including the land of Ibu Siji’s family (, Map 4). The example of Kedungwringin is not an isolated case, but a typical illustration what happened across all of Indonesia. Sempor Dam was only one of 33 large dams built in Indonesia between 1972 and 1990 (Aditjondro Citation1998, 30–31), and just five of these dams alone were responsible for evicting 100,000 villagers from their land (Aditjondro Citation1993, 12; Magee Citation2015, 230).

Like the capitalist creation of forest land for ‘productive use’, so too did agricultural modernization benefit some Indonesians, at the expense of others. Those who did benefit, summarized by Rachman as only 20–30% of Indonesia’s rural population, managed to accumulate more capital and land (Rachman Citation1999, 166–167), and invested their capital in non-agricultural sectors (Hűsken and White Citation1989, 36). The resulting social differentiation in the countryside is clearly manifest in the gradual rise in the percentage of landlessness among Indonesia's peasants: from 21% to 30% to 36% of the agricultural/rural population in 1983, 1993, and 2003, respectively. This trend is also reflected in Indonesia’s Gini ratio of landholdings of 0.64, 0.67, and 0.72 for the same years (Bachriadi and Wiradi Citation2013, 50). The few, but increasingly powerful, beneficiaries of the capitalist agricultural production helped to secure the New Order regime (Hűsken and White Citation1989; Rachman Citation1999, 167).

When remembering how the Sempor Dam caused the expropriation of village land, Ibu Siji herself describes it as a process of dispossession – sawah ditenggelamkan, dibebaskan begitu aja – which means: the sawah was flooded, it was made free (from us). Although considered unjust, she said her family was afraid to resist or protest. Ibu Siji’s story echoes that of other people we spoke to in Jakarta. In our interviews, of the 76 respondents coming from villages, 55 came from households who did not have access to land for production. For many, the dispossessions they experienced in their home villages formed the start of a spiral of marginalization and impoverishment. In Indonesia as a whole, these dispossessions happen(ed) through the largescale allocation of land to state and non-state actors, i.e. for the use of plantation, forest conservation, logging, extraction of minerals (mining), energy (oil, gas and geothermal), infrastructure development and military occupation (KPA Citation2020) and ‘intimate’ exclusions between villagers motivated by expansion of commercial tree crops such as cocoa and oil palms (Li Citation2014).

5. Socionatural transformations under/through New Order

The second set of processes responsible for making it ever more difficult to make a living in the countryside are intimately related to the first. They relate to how the development of capitalism changes – works through – the environment (Angelo and Wachsmuth Citation2015; Tzaninis et al. Citation2020). These socionatural transformations are the combined effect of the sociospatial reconfigurations we described above: ecological degradation and the deterioration of ecological functions.

A first form of ecological degradation in Kedungwringin is the steady decrease in land fertility, caused both by commercial forestry and commercial agriculture (irrigation water and dam development). In the 1970s, Perhutani replaced native tree species – Jati (Tectona grandis), Angsana (Pterocarpus indicus), and Juar (Senna siamea) – with Pinus. One of the arguments for this replacement was to conserve the catchment area (Perhutani Citation2015, xv and Lampiran PDE-2). Yet, the Pinus tree produces allelopathy, a chemical which makes Pinus outcompetes other plants in their search for soil nutrition (Fisher Citation1987). As was explained by a Kedungwirin villager, the Pinus tree also outcompetes other plants in capturing water and sun. In addition, Pinus tree leaves have a tough, wax-coated cuticle, making their natural decomposition slow and difficult. As a result, even though Perhutani employs the ‘tumpang sari’ system (Peluso Citation1988, 68; Peluso and Purwanto Citation2018, 32), i.e. allowing villagers whose land was enclosed by the forest to plant crops below the Pinus trees, yields are very low. One villager we spoke to told us how his yield of cassava under the Pinus tree is 70% less compared with that outside of Pinus plantation areas.

Changes in water flows are a second socionatural transformation which is directly linked to the sociospatial reconfigurations caused by political forests and political water. Villagers we spoke to report their wells drying up, with the flow of water in springs and rivers in the dry season only half of what they used to be before Pinus were planted. They attribute these changes in hydrology to the planting of Pinus trees in the upland area of Kedungwringin. Indeed, a study carried out elsewhere seems to confirm that Pinus trees both consume more water than many other crops, while also reducing percolation and runoff. This decreases the availability of groundwater in nearby wells, and reduces discharge into springs and rivers (Huber, Iroumé, and Bathurst Citation2008).

Water is not only drying up in the places where villagers need it, at times there is also too much water. With land previously used for growing rice now enclosed by the Sempor Dam and reservoir, villagers plant padi (rice), corn, cassava and peanuts in the reservoir area – on so-called ‘project’s land’ (tanah proyek) – in the dry season, when the water level falls. This is a risky practice, for when the water levels in the reservoir rise, their plants risk getting flooded. Inundation of the crops is more frequent since 2008, so villagers’ crops get damaged not only at the end of the rainy season when levels in the Sempor Dam rise, but (as we saw ourselves in October 2017) can get flooded after only three days of rain. This is the continuing impact of Sempor Dam, which – in 2008 – required a sediment dam to be built upstream, to maintain functionality for those reliant on water supply, electricity, and irrigation water (, Map 4). The impact of this sediment dam for those villagers who rely on land in the project’s area is that their crops gets flooded more frequently. Farmers not just lose their crops, but also their investments of time and labour. One farmer we talked to had lost three million IDR (around 210 USD according to mid-2020 currency) over one rainy season. This includes the labour undertaken by himself and his family to cultivate the rice, corn, cassava, and peanut seeds.

Who benefits from the loss of the farmers? Sustaining the production capacity of Sempor Dam (1 Megawatt installed capacity) is crucial for the profits of the electricity company of Indonesia Power, a subsidiary of the National Electricity Company/PLN (Indonesia Power Citation2016, 26). The three municipal water supply companies who rely on the reservoir for the raw water to supply their piped water services also need the dam to function for their profits. The dam supplies 150 l/s of water for the municipality water companies of Gombong, Karanganyar, and Kebumen, all located downstream (PDAM Kebumen Citation2017). The annual revenues (if there is a surplus) should go to local governments, ostensibly to invest in expansion. In practice, it is now widely recognized that they are often used to line the pockets of officials or finance election campaigns.Footnote1 But while the land and crops of Kedungwringin, and the other villages upstream of Sempor Dam, are sacrificed to produce electricity and water supply (and profits of the companies), their access to these services is very limited. During our stay in Kedungwringin we were often without electricity from PLN, sometimes for the entire day and night. As for water: access to it is highly uneven in Kedungwringin. A few residents can afford to dig deep wells to secure their water needs. The rest rely on the intermittent supply of piped water to the village water tank, often standing in line for more than two hours during morning rushes to fill their containers.

Not all in Kedungwringin experience the effects of these changes in the same way. The case of Pak Loro (pseudonym), a forest labour foreman (mandor sadap) of Perhutani, can serve to illustrate a ‘qualitative’ form of agrarian differentiation that happened through a change in ‘relations’ (White Citation1989, 20) between villagers. Pak Loro was born in Kedungwringin in 1965; in Hart’s (Citation1988, 263) words, he managed ‘to access the resources and patronage of the state’ and therefore never migrated to a big city. He spent 6 years in elementary school in Kedungwringin and another 3.5 years in the technical school in the nearby town of Gombong. After his education, he joined a dam development project in the nearby sub-district of Wadas Lintang for one year, before coming back to Kedungwringin. In 1990, he was lucky enough to join Perhutani, when the company sought local employees. At the time of interview he was a mandor sadap, and his main responsibility is to increase Perhutani’s production. He organizes regular meetings every 36 days among his fellow villager Pinus tappers, to persuade them to keep tapping even in times of low prices. He forms the bridge between Perhutani and the tappers, making sure that all the needed tools are available for the tappers, as well as organizing the collection of the product, the resin of the Pinus trees. Perhutani pays him regularly and enough to allow him to expand, for instance by paying fellow villagers to work for him in his recent experiment with growing around 1,000 coffee trees under the Pinus trees of Perhutani. The employment of villagers by the very companies responsible for sociospatial and socionatural configurations is the ‘mechanism’ (White Citation1989, 26) through which processes are entangled with qualitative social differentiation between villagers to create or accelerate social inequalities.

As we showed for the sociospatial reconfigurations prompted and required by capitalist development, the socionatural transformations we identify are also not specific to Kedungwringin. At the national scale, the repeated forest fires in Sumatra and Kalimantan (Gellert Citation1998) are other forms of ecological deterioration that can be characterized as (part of) ongoing socionatural transformations. The forest fires of 1997–1998 in Central Kalimantan, for instance, took place on land deforested to make place for irrigation canals as part of the 1990s agricultural modernization projects of Suharto’s ‘Million Hectare’ Peat Land Development Project. Deforestation, landscape reconfiguration, and irrigation canal development combine to allow land enclosures and commodification typical for processes of accumulation by dispossession, but they also transform ecological processes: canal networks drain the peat lands, leading to the oxidation of organic matter and the formation of acid that in turn causes the rapid decomposition of peat, making it highly flammable (McCarthy Citation2013, 197; Goldstein et al. Citation2020).

Socionatural transformations thus draw attention to how nature is metabolized through social processes: the production of timber from forests, or the production of water and energy from dams entail the production of new natures, new landscapes. In Kedungwringin both the political forest and dam development provoked changes in water flows and caused ecosystem degradation. PU conceptualizes these forms of extended urbanization as operational landscapes: the production of spaces or territories needed to sustain densely populated cities (Brenner Citation2014, 20). These operational landscapes therefore exist in function of large cities and mega-urban regions, to which we now turn.

6. Connecting country to city: sociospatial and socionatural differentiation

Together, dispossessions and degradations mark processes of development in the Indonesian countryside that make it ever more difficult to make a living here while also spurring processes of social differentiation. Like Ibu Siji, 25 out of 30 interviewees in Kedungwringin have experience of migration (merantau) to big cities with the majority of them (19) to Jakarta, working in informal sectors – in search of alternative possibilities to earn incomes and make a living. In Jakarta (but also in other cities, like Semarang), the only places they could and can afford to live and dwell are settlements precariously situated along or on top of river and water retention banks. By doing so, they contributed in transforming the city socionaturally, making it more prone to floods. These socionatural transformations in both rural and urban areas are entangled with the sociospatial reconfigurations caused by the expansion of Jakarta’s boundaries into the surrounding areas of the Jabodetabek agglomeration, which in the early 2000s already had a total population of almost 30 million (Rukmana Citation2013).

The city’s official population increased from less than 3 million in the 1960s to more than 10 million in the 2000s (BPS Citation2021). Much of this increase comes from processes of migration illustrated by Ibu Siji. Yet, the majority of urban poor migrants remain undocumented, as less than 10% of all migrants eventually register at the Jakarta municipality (Kompas Citation1977, Citation1985, Citation2003). In the 1970s, migration contributed more than half of Jakarta's population increase (Papanek Citation1975, 1). Many of those migrants come from rural areas: 63% of the 3,197 registered or official migrant residents and 80% from the 1,180 unregistered migrant residents indicated having come from the countryside (Temple Citation1975). As in other countries, the COVID-19 crisis in Indonesia has made some of these rural migrants more visible. In April 2020, 600,000 Central Java Province migrants returned to their villages mainly from Jabodetabek (Gea et al. Citation2020); in Kedungwringin 90 migrants had returned, also from Jabodetabek (Whatsapp conversation with villager, April 15th, 2020).

In this way, we see urban precarity and unevenness as causally linked to the uneven outcomes of development processes in the countryside: those residents of the city who are most vulnerable to eviction or flooding (or both) are also the ones who have been previously dispossessed – ‘evicted’ from their rural villages – to make place for those deemed worthier of state support and protection: capitalist entrepreneurs and investors, many of whom have connections to the New Order regime. Through a theoretical focus on the process of urbanization, it becomes possible to trace and acknowledge such connections, showing how urbanization is dialectically linked to the systematic expropriation of the rural population, depriving them of their ability to provide subsistence for themselves, and forcing them to seek employment for livelihoods in the city’s informal sector. This, in turn, allows an understanding of the unevenness of urbanization as the outcome of systematic processes of accumulation by dispossession: the creation of a highly mobile and vulnerable category of people – the majority of KMK, who depend on irregular work to make a living.

Classical theories of primitive accumulation explain how the labour of the dispossessed will be absorbed in manufacturing, seeing dispossession as a ‘point of departure’ (Marx (Citation[1867] 1982: 873)) for industry. As Li has noted in her study of land dispossession in rural Asia, many people excluded from land in their villages are not fully absorbed in factories; their labour is in excess of requirements: ‘places (or their resources) are useful, but the people are not’ (Li Citation2009, 69). Across Indonesia, scholars have calculated an increase in the country’s stagnant RSP, particularly since the start of New Order regime, from 5 million in 1986, 9 million in 1996, 14 million in 2001, 16 million in 2006, and 20 million in 2014 (Habibi and Juliawan Citation2018). Scholars of postcolonial cities similarly note how a gradual disconnect of capital from labour hinders the transformation of peasants into wage labourers: they instead become a RSP as capital is increasingly invested in infrastructure and real estate rather than in factories (Schindler Citation2017). This differs from experiences of urbanization in Northern countries, where those dispossessed by land enclosures in the countryside were absorbed in cities’ industrial sector. In Indonesia, many of the rural migrants going to the city depend on jobs in the informal sector to make ends meet.

7. Conclusion: connecting rural and urban struggles

In this article we explore how theories of urbanization can help to create a politically useful narrative of uneven development across Indonesia. Inspired by theories and methodologies that question urban-rural divides, our first contribution is documenting the connections between uneven development processes in the city and those in the countryside. We do this by showing how the existence of precarious urban settlements is related to the enclosures of rural land and processes of environmental degradation. Increased landlessness and deteriorated ecological functions in the countryside produce waves of migrants who settle on marginal flood prone urban land. Without secure land tenure and through their production as ‘unproductive’ subjects, they are continuously threatened by future evictions. We used the village of Kedungwringin to present empirical moments through which these relations can be illustrated and traced, as well as an entry point through which to document these processes nationally and in ways that link shared experiences of rural enclosure (e.g. political forest and political water) and urban dispossession induced by flood management politics. We explain these urbanization processes of sociospatial and socionatural change and differentiation as integral to the specific form of capitalist development of Indonesia’s (post-) New Order regime.

Our second contribution is three-fold and relates to bringing critical urban studies in conversation with critical agrarian studies to understand the dialectical nature of urban-rural dispossession and related social differentiation. First, we argue that the dangerous ‘urban age thesis' - with it’s tendency to accept the rural-urban divide - is not only adhered to by urbanization scholars such as Mike Davis as we highlighted above, but also by agrarian scholars (see for instance Bernstein Citation2010: 2). Second, this approach enabled us to nuance and qualify the ‘relative surplus population’ (RSP) through the lenses of agrarian studies of capitalist relations (Li Citation2009) and critical urbanization (Ghosh and Meer Citation2020), and building on the critique of urban informality (Bhalla Citation2017) and development of Indonesia’s RSP (Habibi and Juliawan Citation2018). The paper identified informal workers as the ‘stagnant RSP’ that corresponds with the Indonesian urban term of Kaum Miskin Kota/KMK (Lane Citation2010). Third, it was argued how processes of urban precarity and rural differentiation are mutually reinforcing under the specific capitalist development of Indonesia’s (post-) New Order regime. This observation calls for an iteration of the PU thesis in order to nuance planetary, path dependent processes of urbanization by situating them in post-colonial transformation settings and showing the distinctive processes of social differentation (Li Citation2014). Our nuancing of the PU thesis helps recognize the distinctly Western origin of prevailing conceptualizations of urbanization. This most clearly shows in the emphasis on industrialization as a main driver of urbanization and in the belief that the dispossessed will be absorbed by industry's demand for labour (Marx and Engels Citation[1848] 2008, 33–66; Engels Citation1872, 3; Marx Citation[1867] 1982, 866; Lefebvre Citation1996; Amin Citation1976, 203–204; Schindler Citation2017, 6–7). As other scholars have already noted, this enables a focus on post-colonial transition narratives in line with what Amin (Citation1976, 206) and Davis (Citation2006, 14) identify as ‘urbanization without industrialization’; the destruction of pre-existing agrarian society on one side, and the insufficient capacity of industry to absorb the dispossessed on the other.

Questioning and asking for alternatives to forms of development that are uneven and exploitative requires broadening bases of political support. This is even more important, and yet also more difficult, in an era of tightening political control by the national government and the closing down of spaces of dissent (Wijayanto et al. Citation2019). Perhaps there is nevertheless some hope in the collective impacts of COVID-19 measures in Indonesia, and the disarray of government responses. Moments that fuel the hope of better connections between rural and urban social movements include the collective solidarity movement that emerged during COVID-19; the resistance to labour union busting and environmental destruction; and the enactment of the omnibus bill on job-creation. The nascent example of the anti-reclamation movement in Jakarta Bay mentioned in the opening part of this article should ally with all of these movements. These coalitions can be organized in terms of resisting the state role in rural land dispossessions, deforestation, massive replanting, and flooding; areas which we have identified as critical in the ‘rural part’ of the paper. Although patronage relationships, combined with the fact that some benefit from state support while others do not, divides class relations which in turn risks weakening and obstructing a more ‘peasant-driven’ type of social movement. The current reforms threaten to further a form of development which discards environments, and the people dependent on them, while delivering great benefits to a few. Asking whether this is really ‘development’, both rural and urban based movements are now seeing their own struggles are one, reflected in and related to each other.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank UPC/JRMK and Ciliwung Merdeka network for facilitating research in Jakarta; Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP) for funding doctoral study of the first author; Arupa, The Indonesian Institute of Sciences, our colleagues at Water Governance Department at IHE-Delft Institute for Water Education, the 2019 scholar-activists Writeshop-Workshop (co-organized by: Journal of Peasant Studies, College of Humanities and Development Studies, China Agricultural University [Beijing], and Future Agricultures Consortium), and the 2020 Rujak Centre for Urban Studies and Antipode ‘Sekolah Urbanis’, all for discussing the early idea of this article; Noer Fauzi Rachman for endless discussion about agrarian movement; and three anonymous reviewers whose comments facilitate the strengthening of article’s internal logic. Responsibility for the final version stays with us.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Bosman Batubara

Bosman Batubara, Department of Water Governance, IHE-Delft Institute for Water Education, Delft and the Department of Human Geography, Planning and International Development, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Bosman is finalizing his dissertation: Near-South Urbanization: Flows of people, water, and capital in and beyond (post-) New Order Jakarta.

Michelle Kooy

Michelle Kooy, Department of Water Governance, IHE-Delft Institute for Water Education, Delft, The Netherlands, and guest researcher in the Amsterdam Institute of Social Sciences Research, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Michelle has been engaged in issues of urban environmental justice in Jakarta since 2004.

Yves Van Leynseele

Yves Van Leynseele, Department of Human Geography, Planning and International Development, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Margreet Zwarteveen

Margreet Zwarteveen, Department of Water Governance, IHE-Delft Institute for Water Education, Delft, and Amsterdam Institute of Social Sciences Research, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Ari Ujianto

Ari Ujianto, Masters in Sociology from the University of Indonesia, and works as a staff organizing and capacity building in the National Network for the Domestic Workers Advocacy (JALA PRT) and as a board member of the Urban Poor Consortium (UPC). Both of these institutions focus and concern on the urban poor community, and have network in Indonesian big cities. In these two institutions, he more often does the task of providing training or capacity building for community organizers.

Notes

1 Conversation with an Indonesia’s drinking water expert (June 23, 2020).

References

- Abeyasekere, Susan. 1989. Jakarta: A History. Singapore: Oxford University Press.

- Aditjondro, George Junus. 1993. “The Media as Development ‘Textbook’: A Case Study on Information Distortion in the Debate about the Social Impact on an Indonesian Dam”. PhD dissertation, Cornell University.

- Aditjondro, George Junus. 1998. “Large Dam Victims and Their Defenders: The Emergence of Anti-dam Movement in Indonesia.” In The Politics of Environment in Southeast Asia, edited by Philip Hirsch and Carol Warren, 29–54. New York: Routledge.

- Amin, Samir. 1976. Unequal Development: An Essay on the Social Formations of Peripheral Capitalism. Sussex: The Harvester Press Limited.

- Angelo, Hillary, and David Wachsmuth. 2015. “Urbanizing Urban Political Ecology: A Critique of Methodological Cityism.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 39 (1): 16–27.

- AS (Agrarian South: Journal of Political Economy). 2012. “The Agrarian Question: Past, Present and Future.” Agrarian South: Journal of Political Economy 1 (1): 1–10.

- Ascher, William. 1998. “From Oil to Timber: The Political Economy of Off-Budget Development Financing in Indonesia.” Indonesia 65: 37–61.

- Azuma, Yosh. 2000. “Socioeconomic Changes Among Beca Drivers in Jakarta, 1988–98.” Labour and Management in Development Journal 1 (6): 1–31.

- Bachriadi, Dianto, and Anton Lucas. 2001. Merampas Tanah Rakyat: Kasus Tapos dan Cimacan. Jakarta: KPG.

- Bachriadi, Dianto, and Gunawan Wiradi. 2013. “Land Concentration and Land Reform in Indonesia.” In Land for the People: The State and Agrarian Conflict in Indonesia, edited by Anton Lucas and Carrol Warren, 42–92. Ohio: Ohio University Press.

- Bakker, Maarten, Satoko Kishimoto, and Christa Nooy. 2017. Social Justice at Bay: The Dutch Role in Jakarta’s Coastal Defence and Land Reclamation Project. Both Ends, Somo and TNI.

- Barr, Christopher M. 1998. “Bob Hasan, the Rise of Apkindo, and the Shifting Dynamics of Control in Indonesia’s Timber Sector.” Indonesia 65: 1–36.

- Batubara, Bosman, Michelle Kooy, and Margreet Zwarteveen. 2018. “Uneven Urbanisation: Connecting Flows of Water to Flows of Labour and Capital Through Jakarta’s Flood Infrastructure.” Antipode 50 (5): 1186–1205.

- Batubara, Bosman, and Noer Fauzi Rachman. under review. “Extended Agrarian Question in Concessionary Capitalism: The Jakarta’s Kaum Miskin Kota.” Agrarian South: Journal of Political Economy.

- Bernstein, Henri. 2010. Class Dynamics of Agrarian Change. Halifax: Fernwood and Kumarian Press.

- Bhalla, Sheilla. 2017. “From ‘Relative Surplus Population’ and ‘Dual Labour Markets’ to ‘Informal’ and ‘Formal’ Employment and Enterprises: Insights About Causation and Consequences.” Agrarian South: Journal of Political Economy 6 (3): 295–305.

- Borras Jr., Saturnino M., Marc Edelman and Cristóbal Kay. 2008. “Transnational Agrarian Movements: Origins and Politics, Campaigns and Impact.” Journal of Agrarian Change 8 (2–3): 169-204.

- BPS (Biro Pusat Statistik). 2021. “Jumlah Penduduk Provinsi DKI Jakarta Menurut Kelompok Umur dan Jenis Kelamin 2018–2019.” Accessed 14 February 2021. https://jakarta.bps.go.id/indicator/12/111/1/jumlah-penduduk-provinsi-dki-jakarta-menurut-kelompok-umur-dan-jenis-kelamin.html.

- Breman, Jan, and Gunawan Wiradi. 2004. Masa Cerah dan Masa Suram di Pedesaan Jawa. Jakarta: LP3ES dan KITLV-Jakarta.

- Brenner, Neil. 2014. Implosions/Explosions: Towards A Theory of Planetary Urbanization. Berlin: Jovis.

- Brenner, Neil and Schmid, Christian. 2014. “The ‘Urban Age’ in Question.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 38 (3): 731–755.

- Davis, Mike. 2006. Planet of Slums. London: Verso.

- Diantoro, Totok Dwi. 2011. “Quo Vadiz Hutan Jawa.” Wacana 25 (XIII): 5–26.

- DPU (Departemen Pekerjaan Umum). 1993. Bedungan Serbaguna Sempor. Jakarta: Departemen Pekerjaan Umum Direktorat Jenderal Pengairan Direktorat Irigasi II Badan Pelaksana Proyek Serbaguna Kedu Selatan.

- Engels, Friedrich. (1970) 1976. “The Peasant Question in France and Germany.” In Selected Works, edited by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Vol. 3, 458–476. Moscow: Progress Publisher.

- Engels, Friedrich. 1872. “The Housing Question.” Accessed 15 September 2020. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/Marx_The_Housing_Question.pdf.

- Farid, Hilmar. 2005. “Indonesia’s Original Sin: Mass Killing and Capitalist Expansion, 1965–66.” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 6 (1): 3–16.

- Fisher, F. Richard. 1987. “Allelopathy: A Potential Cause of Forest Regeneration Failure.” ACS Symposium Series 330: 176–184.

- Gea, Cornelius, Mila Karmilah, Nur Laila Hafidhoh, and Seniman Martodikromo. 2020. Komunike Covid-19 Kobar. Yogyakarta: Lintas Nalar.

- Gellert, Paul K. 1998. “A Brief History and Analysis of Indonesia's Forest Fire Crisis.” Indonesia 65: 63–85.

- Gellert, Paul K. 2003. “Renegotiating a Timber Commodity Chain: Lessons from Indonesia on the Political Construction of Global Commodity Chains.” Sociological Forum 18 (1): 53–84.

- Ghosh, Swarnabh, and Ayan Meer. 2020. “Extended Urbanisation and the Agrarian Question: Convergences, Divergences and Openings.” Urban Studies 58 (6): 1097–1119.

- Goh, Kian. 2019a. “Urban Waterscapes: The Hydro-Politics of Flooding in a Sinking City.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 43 (2): 250–272.

- Goh, Kian. 2019b. “Flows in Formation: The Global-Urban Networks of Climate Change Adaptation.” Urban Studies 57 (11): 2222–2240.

- Goldstein, Jenny E., Laura Graham, Sofyan Ansori, Yenni Vetrita, Andri Thomas, Grahame Applegate, Andrew P. Vayda, Bambang H. Saharjo, and Mark A. Cochrane. 2020. “Beyond Slash-and-Burn: The Roles of Human Activities, Altered Hydrology and Fuels in Peat Fires in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia.” Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 41 (2): 190–208.

- Goonewardena, Kanishka. 2014. “The Country and the City in the Urban Revolution.” In Implosions/Explosions: Towards A Theory of Planetary Urbanization, edited by Neil Brenner, 218–231. Berlin: Jovis.

- Habibi, Muhtar, and Benny Hari Juliawan. 2018. “Creating Surplus Labour: Neo-Liberal Transformations and the Development of Relative Surplus Population in Indonesia.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 48 (4): 649–670.

- Hart, Gillian P. 1978. “Labor Allocation Strategies in Rural Javanese Households”. PhD dissertation, Cornell University.

- Hart, Gillian. 1988. “Agrarian Structure and the State in Java and Bangladesh.” The Journal of Asian Studies 47 (2): 249–267.

- Harvey, David. 1996. Justice, Nature & the Geography of Difference. Cambridge: Blackwell.

- Hiariej, Eric. 2003. “The Historical Materialism and the Politics of the Fall of Soeharto.” Master thesis, Australian National University.

- Huber, Anton, Andrés Iroumé, and James Bathurst. 2008. “Effect of Pinus Radiata Plantations on Water Balance in Chile.” Hydrological Processes 22: 142–148.

- Hugo, Graeme J. 1982. “Circular Migration in Indonesia.” Population and Development Review 8 (1): 59–83.

- Hűsken, Frans, and Benjamin White. 1989. “Ekonomi Politik Pembangunan Pedesaan dan Struktur Agraria Jawa.” PRISMA 4: 15–37.

- Indonesia Power. 2016. 2016 Statistic Report. Jakarta: Indonesia Power.

- “Jakarta Masih Ditembus Pendatang Baru”. Kompas, February 22, 1977: III.

- Jansen, Kees. 2014. “The Debate on Food Sovereignty Theory: Agrarian Capitalism, Dispossession and Agroecology.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 42 (1): 213–232.

- Kautsky, Karl. (1899) 1988. The Agrarian Question (in two volumes). Translated by Pete Burgess. London: Zwan Publications.

- KPA (Konsorsium Pembaruan Agraria). 2020. Dari Aceh Sampai Papua: Urgensi Penyelesaian Konflik Struktural dan Jalan Pembaruan Agraria ke Depan (Catatan Akhir Tahun). Jakarta: KPA.

- Kusni, J. J. 2005. Di Tengah Pergolakan Turba LEKRA di Klaten. Yogyakarta: Ombak.

- Kusno, Abidin. 2013. After the New Order: Space, Politics and Jakarta. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press.

- KW (Kedunwringin). 2016. “Profil Desa” (Village Document, unpublished). Kedungwringin.

- Lane, Max. 2010. “Indonesia and the Fall of Suharto: Proletarian Politics in the “Planet of Slums” Era.” The Journal of Labor and Society 13 (2): 185–200.

- Larasati, Rachmi Diyah. 2013. The Dance That Makes You Vanish: Cultural Reconstruction in Post-Genocide Indonesia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Lefebvre, Henri. (1970) 2014. “From the City to Urban Society.” In Implosions/Explosions: Towards A Theory of Planetary Urbanization, edited by Neil Brenner, 36–51. Berlin: Jovis.

- Lefebvre, Henri. 1996. “Industrialization and Urbanization.” In Writings on Cities, edited by Henri Lefebvre and translated by Eleonore Kofman and Elizabeth Lebas, 65–85. Malden: Blackwell Publisher.

- Li, Tania Murray. 2001. “Masyarakat Adat, Difference, and the Limits of Recognition in Indonesia’s Forest Zone.” Modern Asian Studies 35 (3): 645–676.

- Li, Tania Murray. 2009. “To Make Live of Let Die? Rural Dispossession and the Protection of Surplus Populations.” Antipode 41 (S1): 66–93.

- Li, Tania Murray. 2014. Land’s end: Capitalis Relations on an Indigenous Frontier. London: Duke University Press.

- Magee, Darrin. 2015. “Dams: Controlling Water but Creating Problems.” In Routledge Handbook of Environment and Society in Asia, edited by Paul G. Harris and Graeme Lang, 216–236. New York: Routledge.

- Mariana, Anna, and Bosman Batubara. 2015. Seni dan sastra untuk kedaulatan petani Urutsewu. Yogyakarta: Literasi Press.

- Marx, Karl. (1867) 1982. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Vol. I. Great Britain: Penguin Books Ltd.

- Marx, Karl, and Friedrich Engels. (1848) 2008. The Manifesto of the Communist Party. London: Pluto Press.

- McCarthy, John. 2013. “Tenure and Transformation in Central Kalimantan After the “Million Hectare” Project.” In Land for the People: The State and Agrarian Conflict in Indonesia, edited by Anton Lucas and Carrol Warren, 183–214. Athens: Ohio State University Press.

- McLean, Heather. 2018. “In Praise of Chaotic Research Pathways: A Feminist Response to Planetary Urbanization.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 36 (3): 547–555.

- MEF (Ministry of Environment and Forestry). 2018. The State of Indonesia’s Forest 2018. Jakarta: MEF, Republic of Indonesia.

- Merrifield, Andy. 2013. The Politics of the Encounter: Urban Theory and Protest Under Planetary Urbanization. Athens: The University of Georgia Press.

- “Operasi Yustisi ke Rumah Warga Segera Dilaksanakan”. Kompas, December 1, 2003: 17.

- Padawangi, Rita, and Mike Douglass. 2015. “Water, Water Everywhere: Toward Participatory Solutions to Chronic Urban Flooding in Jakarta.” Pacific Affairs 88 (3): 517–550.

- Papanek, Gustav F. 1975. “The Poor of Jakarta.” Economic Development and Cultural Change 24 (1): 1–27.

- PDAM Kebumen. 2017. Kebumen Municipality Water Company Report (unpublished). Kebumen: PDAM Kebumen.

- Peake, Linda, Darren Patrick, Rajyashree N. Reddy, Gökböru Sarp Tanyildiz, Sue Ruddick, and Roza Tchoukaleyska. 2018. “Placing Planetary Urbanization in Other Fields of Vision.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 36 (3): 374–386.

- Peluso, Nancy Lee. 1988. “Rich Forest, Poor People, and Development: Forest Access Control and Resistance in Java.” PhD dissertation, Cornel University.

- Peluso, Nancy Lee. 2011. “Emergent Forest and Private Land Regimes in Java.” Journal of Peasant Studies 38 (4): 811–836.

- Peluso, Nancy Lee, and Agus Budi Purwanto. 2018. “The Remittance Forest: Turning Mobile Labor into Agrarian Capital.” Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 39 (1): 6–36.

- Peluso, Nancy Lee, and Peter Vandergeest. 2001. “Genealogies of the Political Forest and Customary Rights in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand.” The Journal of Asian Studies 60 (3): 761–812.

- Peluso, Nancy Lee, and Peter Vandergeest. 2020. “Writing Political Forests.” Antipode 52: 1083–1103.

- “Pendatang Baru di Jakarta Ditertibkan Setelah Pemilu”. Kompas, May 2, 1992: 7.

- Perhutani. 2015. Revisi Rencana Pengaturan Kelestarian Hutan Kelas Perusahaan Pinus Kesatuan Pemangku Hutan Kedu Selatan untuk Periode 2016 s/d 2023 dan Lampiran PDE-2. Yogyakarta: Perhutani.

- Perhutani. 2019. “Profile Perum Perhutani 2019.” Jakarta. Accessed 22 June 2020. https://drive.google.com/file/d/15G_Pudd0q5WiN0i-b8VUb1k90Vb8yEPR/view.

- Prathiwi, Widyatmi Putri. 2019. “Sanitizing Jakarta: Decolonizing Planning and Kampung Imaginary.” Planning Perspectives 34 (5): 805–825.

- Rachman, Noer Fauzi. 1999. Petani & Penguasa: Dinamika Perjalanan Politik Agraria Indonesia. Yogyakarta: Insist Press, KPA dan Pustaka Pelajar.

- Reddy, Rajyashree N. 2018. “The Urban Under Erasure: Towards a Postcolonial Critique of Planetary Urbanization.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 36 (3): 529–539.

- Rukmana, Deden. 2013. Peripheral Pressures. In Archeology of the Periphery, edited by Yury Grigoryan (Curator), 162–171. Moscow: Moscow Urban Forum.

- Rukmana, Deden. 2015. “The Change and Transformation of Indonesian Spatial Planning After Suharto’s New Order Regime: The Case of the Jakarta Metropolitan Area.” International Planning Studies 20 (4): 350–370.

- Sangadji, Arianto. 2021. “State and Capital Accumulation: Mining Industry in Indonesia.” PhD dissertation, York University.

- Savirani, Amelinda, and Edward Aspinall. 2018. “Adversarial Linkages: The Urban Poor and Electoral Politics in Jakarta.” Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs 3: 3–34.

- Schindler, Seth. 2017. “Towards a Paradigm of Southern Urbanism.” City 21 (1): 47–64.

- Simone, AbdouMaliq. 2014. Jakarta, Drawing the City Near. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Siscawati, Mia. 2014. “Masyarakat Adat dan Perbutan Penguasaan Hutan.” Wacana 33 (Tahun XV): 3–23.

- Sopaheluwakan, Jan, Wahyoe Hantoro, Henny Warsilah, Alan Koropitan, Marco Kusumawijaya, Rameyo T. Adi, Reiza Patters, et al. 2017. Makalah Kebijakan: Selamatkan Teluk Jakarta. Jakarta: Rujak Centre for Urban Studies.

- Temple, Gordon. 1975. “Migration to Jakarta.” Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 11 (1): 76–81.

- Texier, Pauline. 2008. “Floods in Jakarta: When the Extreme Reveals Daily Structural Constraints and Mismanagement.” Disaster Prevention and Management 17 (3): 358–372.

- Tzaninis, Yannis, Tait Mandler, Maria Kaika, and Roger Keil. 2020. “Moving Urban Political Ecology Beyond the ‘Urbanization of Nature’.” Progress in Human Geography 45 (2): 229–252.

- van Voorst, Roanne. 2015. “Risk-handling Styles in a Context of Flooding and Uncertainty in Jakarta, Indonesia.” Disaster Prevention and Management 24 (4): 484–505.

- Vandergeest, Peter, and Nancy Lee Peluso. 2006a. “Empires of Forestry: Professional Forestry and State Power in Southeast Asia, Part 1.” Environment and History 12 (1): 31–64.

- Vandergeest, Peter, and Nancy Lee Peluso. 2006b. “Empires of Forestry: Professional Forestry and State Power in Southeast Asia, Part 2.” Environment and History 12 (4): 359–393.

- “Warga Kota yang Mudik Suka Ajak Kerabatnya Berurbanisasi ke DKI”. Kompas, May 4, 1985: III.

- White, Benjamin. 1977. “Production and Reproduction in a Javanese Village”. PhD dissertation, Columbia University.

- White, Benjamin. 1989. “Problems in the Empirical Analysis of Agrarian Differentiation.” In Agrarian Transformations: Local Processes and the State in Southeast Asia, edited by Gillian Hart, Andrew Turton, Benjamin White, Brian Fegan, and Lim Teck Ghee, 15–30. Berkley: University of California Press.

- White, Benjamin. 2015. “Remembering the Indonesian Peasants’ Front and Plantation Workers’ Union (1945–1966).” The Journal of Peasant Studies 43 (1): 1–16.

- Wijayanto, Rachbini, J. Didik, Malik Ruslan, and Fachru Nofrian Bakarudin. 2019. Menyelamatkan Demokrasi (Outlook Demokrasi LP3ES). Jakarta: LP3ES.