ABSTRACT

Mega-damming, pollution and depletion endanger rivers worldwide. Meanwhile, modernist imaginaries of ordering ‘unruly waters and humans’ have become cornerstones of hydraulic-bureaucratic and capitalist development. They separate hydro/social worlds, sideline river-commons cultures, and deepen socio-environmental injustices. But myriad new water justice movements (NWJMs) proliferate: rooted, disruptive, transdisciplinary, multi-scalar coalitions that deploy alternative river–society ontologies, bridge South–North divides, and translate river-enlivening practices from local to global and vice-versa. This paper's framework conceptualizes ‘riverhood’ to engage with NWJMs and river commoning initiatives. We suggest four interrelated ontologies, situating river socionatures as arenas of material, social and symbolic co-production: ‘river-as-ecosociety’, ‘river-as-territory’, ‘river-as-subject’, and ‘river-as-movement’.

1. Introduction

The focus of this paper is contemporary contestation over control of riverine ecologies and societies. Across time and space, rivers are key sites of conviviality and struggle. Over the past century river systems worldwide have been subjected to multiple forms of domestication, enclosure, erasure, and pollution on an unprecedented planetary scale; human appropriation of fresh water equals half of global riverine discharge (UNEP Citation2016; Abbott et al. Citation2019). This has entailed profound transformation in water quality and flow of rivers, raising key questions about justice. Differential water access, asymmetries in rights, and uneven levels of protection and influence over decision-making are inevitably forged along lines of class, gender, ethnicity, and human/non-human (Crow et al. Citation2014; Venot et al. Citation2021).

Many of these challenges stem from the utopian-infused legacy of conquering riverine natures and societies, silencing and ordering them through mega-hydraulic infrastructure (McCully Citation1996). Large dams are paradigmatic attempts to transform stubborn water unruliness into modern, civilized water control (Worster Citation1985; Kaika Citation2006; Hommes and Boelens Citation2018). More recent discourses that promote damming refer to ‘green development’ and ‘climate change adaptation’ (Mills-Novoa et al. Citation2020), whereby mega-hydraulic projects would bring ‘clean’ energy, water security and flood protection for expanding cities and agro-industries. Besides damming, tremendous pollution of rivers from diverse sources (settlements, intensive agriculture, mining operations, amongst others) lays bare an exploitative view on rivers in line with the commodification of nature (Pomeranz Citation2009; Espeland 1989; Perreault Citation2014). Even though other governance approaches have emerged (‘integrated’, ‘participatory’, ‘nature-based’), these too commonly override the complexities of real-world socio-ecological river systems (Fernandez Citation2014; Jackson Citation2017). Many approaches favor large-scale, neoliberal aspirations, and damage riverine co-existences, while failing to reach their stated social, environmental and economic goals (Woodhouse and Muller Citation2017). The powerful expert ontologies and epistemologies that inform these interventions are all too often entrenched in hydraulic-bureaucratic administrations and capitalist imaginaries. Such ‘hydrocracies’ (Molle, Mollinga, and Wester Citation2009) remain dominant in defining problems and solutions for rivers, often disregarding alternative, locally grounded river knowledges and relationships (Bakker and Hendriks Citation2019; Boelens, Shah, and Bruins Citation2019; Flaminio Citation2021).

Acts of modifying and producing rivers are not in and of themselves the problem: interactive river making, sharing and caring is age-old and basic to all water cultures. Such interaction has shaped urban and rural lives, peasant economies, and amphibious geographies for ages (Barnes and Alatout Citation2012; Aubriot Citation2022). The key consideration is the scale, means, and processes of remaking rivers (Perreault, Wraight, and Perreault Citation2012; Joy et al. Citation2018; Bakker et al. Citation2018; Whaley Citation2022). Affected actors and commons are rendered voiceless when overruled by top-down hydrocracies and market-driven water policies (e.g. McCully Citation1996; Harris Citation2009; Nixon Citation2010).

As a result, diverse societal responses and grassroots mobilizations in and across the Global South and North have emerged. Early contestations of governmental development among farmers of the Senegal River valley were chronicled by Adams (Citation1977, Citation1979). Recent examples include the 430 riverine cases documented in the Environmental Justice Atlas (Martínez-Alier Citation2021; www.ejatlas.org), anti-dam movements from India to the Balkan countries (Del Bene, Scheidel, and Temper Citation2018; Shah et al. Citation2019), river restoration coalitions in the USA, UK and South Africa (International Rivers Citation2021), the ‘rooted water collectives’ from Peru to Morocco (Vos et al. Citation2020), right-of-rivers movements from local to United Nations (UN) levels (Kinkaid Citation2019), or the ‘river-health clinics partnerships’ as in Ecuador, Spain and Colombia (Hernández-Mora et al. Citation2015; Ulloa Citation2020a). These numerous and diverse initiatives are considered together here under the term ‘new water justice movements’ (NWJMs), whereby we deploy the notions of ‘new’ and ‘movements’ not as assertations but as core questions to be scrutinized. Their compositions, foci, creative strategies and experiences are indeed diverse, but all engage in ‘water commoning processes’ to claim environmental justice and to ‘enliven rivers’. That is, they engage in radical collective practices of place and community making, wresting rivers away from influences that enclose, commodify or pollute. While we acknowledge and understand the diversity of these efforts and their strategies we are nonetheless interested in the potential of NWJMs to contribute in novel and compelling ways to context-relevant, grounded, nature-connected and more equitable water governance. At once, we also understand that they are fraught with challenges particularly as these movements and their ideas, principles and practices are often sidelined from legal frameworks, governance debates, and policy innovation processes. Also in academia, social and natural sciences have paid very little attention to these counter forces. There is a corresponding deficiency in terms of action instruments to engage with commoning strategies and linked sociotechnical practices to foster environmental justice (Wals et al. Citation2014; Escobar Citation2020).

We hope to contribute to building a foundational framework that helps to better understand the disruptive river movements and their associated ontologies, practices and sociolegal repertoires. To better conceptualize rivers as key socionatural entities, and NWJMs as a key response to ongoing challenges, our contribution centers around the notion of ‘riverhood’.Footnote1 Riverhood was originally a mid-nineteenth century concept to describe ‘the state of being a river’ (Oxford Dictionary). It is linguistically composed of ‘river’ and the suffix ‘-hood’, where the latter commonly denotes a temporal and/or continuous and unifying state, condition, character or period (as in livelihood, childhood, sisterhood, etc.).

As we will outline, our riverhood concept has four interrelated dimensions that help to disentangle the multiple practices, meanings and fields of contentions in which NWJMs are embedded. NWJMs do not explicitly use the term ‘riverhood’, but they nonetheless employ imaginaries and strategies that relate to the four riverhood ontologies we explicate in the pages that follow. Thinking in terms of riverhood guides inquiry into the different ways that rivers are imagined, defined, built, produced, and lived as socionatural, political-economic, and cultural-symbolic systems. Our work thus aims both to learn from and contribute to key foundations for NWJMs and associated theoretical and political movements.

This paper can be read as the opening to or hopefully the prelude for an enriched conversation and field of inquiry for transdisciplinary research and cross-cultural action focused on riverhood relationships and river movement struggles, including consideration of how these connect to questions of social, environmental and agrarian justice. The contents of this paper are based on our collective three plus decades of river-related fieldwork, as well as on academic and archival literature research; professional, policy and media discourse analysis; and our myriad seminars, workshops and debates with grassroots movements, policy actors, academics and river defense networks. For this paper we, 29 authors rooted in social sciences, natural sciences and grassroots-knowledge arenas, have joined and reflected on our work on politics of water governance in agrarian, human rights, earth jurisprudence and environmental justice fields, spanning numerous countries across six continents. In conversation with an agrarian political economy approach that classically studies agricultural production by questioning ‘Who owns what? Who does what? Who gets what? What do they do with it?’ (Bernstein Citation2010, 22), we broaden our focus in two important ways: we look beyond agriculture at wider interaction with the natural environment; and beyond distributive (socio-economic) and political justice (representation in decision-making) we also look at cultural and epistemological justice (recognition of diverse knowledge, normative, identity and governance frames) and socio-ecological justice (human-non-human entanglements and inter-generational sustainability).

In the following, we first examine the political-historical background of constructing and imagining riverhood, through river domestication schemes and emergent enlivening and re-commoning responses (Section 2). This sets the stage for our conceptual engagement. We then review conceptual debates on socionature commons, commoning and agrarian politics, water justice, hydrosocial territorialization and translocal movements (Section 3). Next, we engage these debates as groundwork to elaborate our analytical framework. It involves four connected and complementary river ontologies that provide a basis to engage with rivers as arenas of material, social and symbolic co-production among humans and non-humans (Section 4). We argue that a better understanding of rivers’ socionatural complexities can contribute to new ways of thinking, feeling, acting and living with rivers. We hope to stimulate possible pathways for the transdisciplinary co-creation of knowledge and multi-scalar action; to support and strengthen conceptualization important for NWJMs in ways that centers these notions in policies and societal debates; and to strengthen and enliven ongoing struggles against socio-environmental injustices.

2. Background: nature domestication, enclosure of river commons, and the emergence of river enlivening movements

A focus on emergent river-centered strategies and practices of NWJMs requires studying encounters over the meanings, values, materialities and governance of rivers. NWJMs respond to the widespread injustices resulting from technocratic approaches and the large-scale river development schemes that marginalize place-rooted collectives and cultures that co-exist with rivers (e.g. Hidalgo-Bastidas et al. Citation2018; Fox and Sneddon Citation2019; Cortesi and Joy Citation2021).

The desire to engineer ideal societies by dominating ‘wild water’ and simultaneously controlling humans and nature has been long associated with European expansion and colonization. In Thomas More’s Utopia (1516), allegorically, King Utopos dug a huge channel isolating peninsula Utopia from barbarian nature. The main river Anydrus and associated springs were all canalized and technified to separate water from human and natural threats. Utopians perfected society and nature by wise social planning (More Citation1975[Citation1516]). Francis Bacon’s New Atlantis (1627) is also iconic. This utopian novel concentrates on the organization of well-being through technological domestication of nature. Bacon in turn motivated Jeremy Bentham, founder of utilitarianism, who defines happiness through mathematics-inspired language, laws and nature relationships (Citation1988 [Citation1781]). Along with John Locke’s advocacy for ‘possessive individualism’ vis-a-vis the ‘unoccupied and unordered wilderness’[Citation1970(1690)], later utilitarian philosophies of humanizing nature continued (cf. Jasanoff Citation2004; Descola Citation2013). Together they denied and often supplanted existing modes of vernacular governance. This epistemic violence justified the colonization and domestication of river commons as places of threats, emptiness, unruliness, and irrational values (Boelens Citation2017). In settler-colonies around the globe, waters that ran ‘wasted’ to the sea were commandeered for ‘modern’ uses benefiting a mostly white citizenry, dispossessing and displacing indigenous and other racialized peoples (Berry and Jackson Citation2018; Behn and Bakker Citation2019).

Since the mid-twentieth century, new technologies have enabled rapid expansion of the ‘mega-hydraulic regime’. Colossal interbasin water transfers and river diversion schemes increasingly interconnect agro-capitalist and hydropower complexes in the so-called ‘water–energy–food nexus’ – aggravating socio-environmental transformation, displacement and agrarian injustice (Allouche, Middleton, and Gyawali Citation2015; Obertreis et al. Citation2016; Duarte-Abadía and Boelens Citation2019; Rodríguez-de-Francisco, Duarte-Abadía, and Boelens Citation2019). These endeavors are focal points for intense conflicts over resources as much as over knowledges and values (Mitchell Citation2002; Shah et al. Citation2019; Hommes et al. Citation2020). Protestors who oppose hydrocratic projects are increasingly criminalized, and alarming numbers of environmental rights activists are even killed (e.g. Del Bene, Scheidel, and Temper Citation2018; Johnston Citation2018; Lynch Citation2019). To date, most attention has been paid to mega-hydraulic river schemes and protests. Yet the more ‘invisible’ policies and their technical repertoires are also influential and require examination and response. An example is the EU Water Framework Directive from 2000 that succeeded in reducing river pollution, but at the same time relies on top-down technocratic implementation (Martínez-Fernández, Neto, and Hernández-Mora Citation2020). In such examples, manifold territorial meanings, values, and rights systems are overlain by modernist governance arrangements, while river ecologies are reframed to fit expert models.

Alternatives to mega-hydraulic works are numerous and widespread. For instance, user-built river waterworks, though not providing cure-all keys, intimately entwine the designer–builder–user worlds. They stem from vernacular (‘local’, ‘indigenous’, ‘peasant’, often hybrid) water cultures’ engagement with nature’s potentials, restrictions, and caprices. Water-access norms and modes of caring for the river have mostly been consolidated through lengthy experience and custodianship practices (Strang Citation2020; Aubriot Citation2022). At the same time, they are not necessarily equitable but produced in harsh, contradictory realities that include power inequalities. The resulting hydraulic works, moral agreements, and organizational frames become manifestations of cultural and legal pluralism that, in turn, drive local water culture and identity formation, and become the fundament for collective action. In other words, the co-production of such river systems through and among human labor, knowledge, technology and nature, humanizes nature and at the same time also changes human relations to and with nature (Pfaffenberger Citation1988; Woodhouse et al. Citation2017).

This widespread practice and important rationale of shaping socionature relations through river works and practices has been taken advantage of by (inter)national ruling groups and nation-building projects. Whereas classic elite groups tended to engage in outright river commons enclosure practices (Marx Citation1972 [Citation1867]), contemporary expropriation and privatization practices are accompanied by ever subtler alignment strategies and cultural politics. Importantly, epistemic frames of the dominant classes are institutionalized and presented as objective and rational water narratives and values. In combination with technocratic decisions, market- and government-aligned identities and neoliberal solutions, they come to appear as normal or inevitable (Swyngedouw Citation2015; Vos and Boelens Citation2018; Gerber and Haller Citation2021). As a result, the diversity of river cultures and rights frameworks are supplanted. Therefore, water justice movements attend to distribution issues (Dell'Angelo et al. Citation2018; Veldwisch, Franco, and Mehta Citation2018) as much as to meanings, discourses and knowledges (Loftus Citation2009; Roa-García Citation2017; Menga and Swyngedouw Citation2018). Scrutiny of dominant water knowledge and ordering regimes – including subtle ‘adverse alignments’ (Hall et al. Citation2015) – becomes fundamental.

Faced with these dominant regimes, riverine communities and coalitions react. These alliances resist, modify and also strategically use the ruling representational order. Wilson (Citation2019), Kramp, Suhardiman, and Keovilignavong (Citation2022) and Pratt (Citation2022) document how trans-local networks sometimes purposefully mimic formal/legal figures, or foment new valuation languages and water rights frames that challenge the predominance and self-evidence of formal state, market-based and scientific frameworks. While several NWJMs build on experiences of environmental organizations that started in the Global North in the 1970s, movements from India to South Africa now deploy radically new river–society ontologies, practices and campaigning methods (e.g. Wals et al. Citation2014; Dukpa et al. Citation2019; Escobar, 2019) (see Box 1).

BOX 1: From rights-of-rivers to human–nature co-creation. River struggles in Colombia.

‘Rivers for life, not for death’ – a worldwide slogan in defence of healthy rivers, against large-scale infrastructure projects – profoundly expresses the notion of rivers as common goods. The Latin American Movement of Dam-Affected People (MAR), joining dozens of (trans)local river commons movements, puts disruptive epistemic, ontological and methodological notions high on the political agenda. Co-creating transformative change is the aim. This entwines everyday environmental justice objectives with the dethroning of colonizing river knowledge. River movements show how concepts emerge from commonplace collective practice as well as from new, creative conceptual interpretations. In Colombia, ‘Ríos Vivos’, ‘Movement for Life and Territorial Defense of Oriente Antioqueño’ and ‘Association of Fishermen, Farmers, Indigenous and Afrodescendant Communities of Bajo Sinu’ (Asprocig), among many others, illustrate the multi-actor, multiscale riverhood struggles against extractive industries and hydropower mega-dams. Numerous riverside communities and movements go beyond resistance and ‘re-existence’, devising alternatives such as a just energy transition, agro-ecological care and riparian eco-fishing economies that build on ‘amphibian ecosystems’ and diverse rights-of-rivers initiatives (Roca-Servat and Palacio Ocando Citation2019). Demands for radical socio-environmental transformations therefore include co-learning in the search of human–non-human conviviality. Exemplary is the case of the Wayúu people who are demanding relational environmental justice for their territory, rivers and springs, embracing all non-humans as living beings with rights to be, feel and exist (Ulloa Citation2021). They entwine territorial, human and more-than-human rights claims against capitalist extractivism, with ontologies that involve profound transformations in the core of the current economic model and development policies.

Alternative living-river and living-with-river proposals range from interconnected user-managed riverworks to dam removals – recently, 5000 river barriers were removed in Europe (DRE Citation2022). Other practices relate to river livelihood and ecological fishing strategies (Buijse et al. Citation2002), protecting ‘amphibious’ river societies (Fals Borda Citation1987; Duarte-Abadía et al. Citation2015), deploying river water culture principles (Martínez Gil Citation2010; Wantzen et al. Citation2016), or mobilizing rights-of-rivers ethics (Anderson et al. Citation2019; Jackson Citation2022). In their agendas, they even include ‘atmospheric-river’ defense (also framed as ‘flying rivers’), in climate justice battles (Lovejoy and Nobre Citation2019; Jackson and Head Citation2021); or the struggle against agro-industries’ ‘virtual-water export’ (e.g. embedded in Kenyan flowers, Peruvian asparagus, or Argentinean meat) (Vos and Hinojosa Citation2016).

We argue that these new trans-localizing water movements require overarching new hydrosocial science, justice approaches and conceptual instruments. These are needed to better apprehend how rivers are networked complexes that are simultaneously material, social and symbolic, and to theorize how NWJMs claim voice for humans and non-humans in these webs of water-life. Only with a better understanding of the past, present and envisaged riverhoods will it be possible to support efforts toward alternatives.

3. Connecting conceptual groundwork

To apprehend how NWJMs defend rivers as socionatural commons and thus understand ‘riverhood’ (i.e. the arena of contested co-production among humans and non-humans of ‘river’), we integrate theoretical debates that so far have been deployed separately. Doing so requires the crossing and deconstructing of boundaries between natural and social sciences, and between academic and vernacular knowledge systems, and the deployment of a hybrid socionatural and techno-political approach to water governance politics. We thereby entwine the conceptual notions of socionature, commons, water and agrarian justice, hydrosocial territorialization, and translocal movements. In the following, we briefly review these notions that have been advanced by diverse scholarly currents and that focus on complementary aspects of riverhood dynamics. Our intention is not to provide a complete literature review, but rather to introduce the notions briefly and to set the groundwork for an alternative, four-fold riverhood framework presented in Section 4.

3.1. Riverine socionature commons, agrarian politics and re-commoning struggles

Nature, society and technology mutually constitute each other to form socionatural and techno-political networks (Latour Citation2004). Humans are part of nature, and nature is part of society. Notions such as ‘naturecultures’ (Haraway Citation1991), ‘waterscapes’ (Swyngedouw Citation2015) and ‘hydrosocial cycles and territories’ (Linton and Budds Citation2014; Boelens et al. Citation2016) express this idea. The boundaries between ‘natural’ and ‘social’ are inevitably fluid as waterflows cross and link physical, political and cultural domains in the myriad river commoning endeavors (White Citation2011; Bakker Citation2012; Wantzen et al. Citation2016). Socionature commons thereby emanate from relations shaped according to values and norms crafted by those taking active part in the process (De Castro Citation2016; Paerregaard Citation2017; Ulloa Citation2020b) (see Box 2). Far from being egalitarian nature-entwined micro-societies in remote places, they are collective endeavors for exercising mutual dependence of nature and society (Escobar Citation2001; De Angelis Citation2012; Agrawal Citation2014). All societies are made up of various socionature commons, mediated by particular resource-use patterns, knowledge frameworks, governance structures and techno-political interventions. Such commons potentially form countervailing (Sandström, Ekman, and Lindholm Citation2017; Sanchis-Ibor et al. Citation2017) or even counter-hegemonic forces that work against state-centric or capitalist-privatized forms of control over nature and humans (Escobar Citation2016; Vos et al. Citation2020; Villamayor-Tomas and García-López Citation2021).

BOX 2: Commoning struggles for re-appropriating territory.

Commons and the associated social practices –commoning– are fundamentally built on excluding market logics from the conditions of life (water, air, food, shelter, knowledge, etc.). The commodification of water in recent decades has unleashed profound political conflicts worldwide. As Karl Polanyi (Citation1944) noted, resistance is a common response when market logic is imposed on socio-ecological relations. Commoning refers to the practices of place- and community-making as a radical alternative to commodification, which establishes exclusive property relations and universally exchangeable, market-transferable goods (Firat Citation2021, 5).

Rivers are subject to multiple forms of commodification. Pollution, damming, and diversions partition holistic socio-ecosystems into discrete resources, privileging some users at the expense of others. Hydropower dams may generate energy for capitalist firms that sell electricity. And river waters are often granted as private rights for mining, commercial agriculture, or domestic use. At times this reaches absurd proportions. For instance, the water volume granted as rights to Colorado river users exceeds the actual river flow. River commoning refers to practices and struggles that resist riverine privatization pressures and aspire to de-commodify private property, rendering rivers non-alienable.

Analytical perspectives traditionally address commoning as a transformative process driven by subaltern groups to address mutually experienced wicked problems that emerge from co-habitation and everyday life practices. But assumptions of local-based, harmonized river commoning overlook power struggles emerging from internal asymmetries, governmentality structures, and ontological clashes, such as in the Magdalena river fisher communities’ battles (Boelens et al. Citation2021). The ‘new commons’ literature (e.g. Bertacchini et al. Citation2012) addresses the relevance of ‘intangible’ issues – such as Perreault’s (Citation2018) work on the performative power of river knowledge, memory and identities in Bolivia.

A practice-based perspective examines river commons as dynamic political arenas addressing both the tangible and intangible commoning issues. Corresponding struggles interlace multiple cosmologies, human/non-human relations, scalar connections, and institutional hybridity. De Castro (Citation2012), for instance, showed how communities’ floodplain re-appropriation and governance practices to address conflicts in the Brazilian Amazon have gained legitimacy among policymakers, fostering collective tenure systems. Rather than an orderly process, river commoning experiences are messy and power-charged processes. Internal and external threats include distributive and decision-making conflicts, such as over irrigation-water access or fishing grounds, and over legitimate territorial rules and authority. In riverine struggles, the political-economic, critical-analytical and practice-based commoning perspectives entwine in myriad ways.

We define river commons as networked socio-ecological arrangements that embrace and mobilize the social and the natural – human and non-human – and practice river stewardship based on their mutual interdependence on shared riverine livelihood interests, knowledge and values. The co-governance (e.g. Gerlak et al. Citation2011; Goodwin Citation2019) of river commons needs a diversity of actors that energize cross-societal river stewardship beyond the hegemonic governance patterns of states, markets and elites (De Castro, Hogenboom, and Baud Citation2016; García-Mollá et al. Citation2020; Suhardiman and Middleton Citation2020; Shi et al. Citation2021). Given the huge capitalist interest in rivers as material and energy sources or as means of transportation, river commoning and co-governance does not occur without conflict as it is deeply contested (Harris and Alatout Citation2010; Harris Citation2012). For instance, river development for agribusiness accommodation and ‘virtual-water export’ (Vos and Boelens Citation2018) is often opposed by peasant communities defending their livelihood sources (e.g. Hoogesteger and Verzijl Citation2015; Veldwisch, Franco, and Mehta Citation2018) (see Box 3).

BOX 3: Political economies of riverine exploitation: agrarian politics, river control and commons defense.

Hydropower development, large-scale land concessions and mega-infrastructure development (e.g. the Lao–China Railway) have not only changed the riverine ecosystems in the Mekong, they have also penetrated into processes of agrarian change, as local communities and farm households struggle to cope with a range of socio-environmental impacts from these nation-building projects (Borras, Edelman, and Kay Citation2008). For example, in Laos, hydropower development and large-scale land concessions (e.g. rubber) have resulted in the resettlement of rural households and massive land grabbing (Suhardiman and Rigg Citation2021). Here, state development agendas override customary rights systems, fiercely impacting community’s livelihoods. Communities’ strategies to cope with these impacts include how they reactivate past political connections (Baird and LeBillon Citation2012), mimic the state’s territory-making through territorialization from the ground up (Kramp, Suhardiman, and Keovilignavong Citation2022), or resist the state’s interferences within their spaces (Kenney-Lazar, Suhardiman, and Dwyer Citation2018). These strategies in highly adverse contexts reveal not only various arenas of contestation but also how local communities reshaped the boundaries of the respective socio-ecological systems (e.g. upland, riverine ecosystem) while placing interconnected rights systems as an integral part of river basin commoning.

Local communities in Northern Laos strategically functionalized state land concession rules (e.g. prioritizing rubber) as their means to protect and reclaim farmlands. In other cases, referring to state policy on national protected areas, local communities have stopped land grabbing in their village, while relying on their political connection. While these strategies do not result in widespread social mobilization, they do represent the rationale behind communities’ strategies to reclaim their rights by linking riverine and upland socio-ecological systems as part of their broader river commoning approach.

3.2. Water justice

Next to understanding riverine (re-)commoning struggles, a focus on the diversity and complexity of riverine inequalities and marginalization invites a situated transdisciplinary justice perspective – one that is based on on-the-ground, rooted governance realities and locally experienced water (in)justices. We therefore move away from universalistic notions of what justice ‘should be’, to embrace relational concepts constituted in river-based contexts and practices, including also a comparative and historical approach (Mollinga Citation2008; Zwarteveen and Boelens Citation2014; Jepson et al. Citation2017). This shift turns our gaze to how diverse river societies and cultures see and define justice within river settings (including their spatial and temporal scales, Krause Citation2013; Ertör Citation2021), and how justice-for-nature is conceived. By doing so we hope to unveil and expose the realities of injustice as experienced by the politically excluded, the culturally discriminated and the economically exploited – both humans and non-humans (Boelens et al. Citation2018).

Our frame, therefore, crosscuts social and natural river justice dynamics. Social and ecological river communities not only depend on and co-constitute each other, they also co-experience multiple (in)justices: in terms of distributive justice (allocation to societal and ecological riverine entities; unequal material effects for nature and specific human groups), political justice (human and non-human representation; their lack of voice and power in decision-making), cultural justice (recognition of diverse normative, identity and governance frames, attached to humans and natures as subjects; the misrecognition of their values and worldviews), and socio-ecological justice (inter-generational sustainability and ecological integrity; the undermining of dignified living and functioning of current and future generations) (Fraser Citation2005; Schlosberg Citation2013; Zwarteveen and Boelens Citation2014). Though constituting different domains of justice, they are intimately connected and make clear how ecological sustainability deeply connects to questions of solidarity and justice. They show how ‘social’, ‘agrarian’, and ‘environmental’ justice issues interact with each other. In fact, riverine quantity/quality inequalities, norms- and rights-based discrimination, and decision-making injustices are distributed along class, caste, gender and ethnicity lines but, simultaneously, humans and nature communities (entwined as socionature commons) co-suffer from environmental crises (Schmidt and Peppard Citation2014; Roth et al. Citation2018).

In terms of the diverse layers and realms of justice, river territories operate in contexts of legal, cultural and institutional pluralism despite the often strongly uniform state-centric and market-based legal frameworks in which they are nested (Roth et al. Citation2015). This becomes manifest in myriad hybrid river governance rules and institutions, product of ‘legal forum shopping’ and ‘bricolage’ (Cleaver and deKoning Citation2015). Water rights, principles and authorities, of different sources and backed by different powers, co-exist and interact in the same hydro-territorial arena. They form a dynamic mixture, entwining local, national and global rules, or indigenous, colonial and recent norms. Thereby, they absorb and reconstruct outside rules and norms to shape grounded local law. These normative systems often defend non-commodity water institutions as their pillars – even when strategically engaging the market (Wolf Citation2009; Suhardiman, Nicol, and Mapedza Citation2017). Despite the simultaneous presence of internal injustices and struggles, they seek collective control through context-grounded institutionalizations.

This multiplicity of river governance norms, rules and authorities disturbs bureaucratic control and capitalist market rule. These predominant governance modes ask for de-localized water rules and river control uniformity void of vernacular-cultural values and complexities born of heterogeneous hydrosocial relations. The respective de-commoning project subjugates or encapsulates diverse grassroots river authorities, rights and norms as it simultaneously treats water as if it were the same everywhere. In plural practice, this triggers profound (overt and covert) conflicts that are not just conflicts over access to resources, such as water, hydraulic, material and financial resources. On a second ‘echelon’, they are also conflicts over the contents of river governance rules and rights (those that move the first echelon’s riverine resources). Next, a third echelon relates to the struggle over riverine authority and legitimacy (which define the second echelon’s rules and rights). Finally, a fourth echelon constitutes the clash among river-existential discourses and worldviews, those that define the ‘right’ environmental policies and ‘truthful’ water governance regimes (legitimizing the third echelon’s rule-making authorities and hierarchies). These four echelons, and the battles over their contents, are intimately connected (Zwarteveen and Boelens Citation2014). The fourth and most abstract layer, i.e. the struggle over power-knowledge regimes (Foucault Citation1980), strives to install a consistent river governance worldview that overarches the three foregoing echelons. The high stake is to render one knowledge, ontological and governance frame ‘natural’, as the morally or scientifically ‘best order’, invalidating all others. These dominant river discourses seek to establish concepts, actors, objects, their identity and relations and hierarchy: they endeavor to shape people’s feeling, thinking, seeing, talking and behaving in relation to river systems – so as to secure one particular socionatural order.

3.3. Hydrosocial territorialization and translocal justice movements

This brings us to how riverine systems are shaped and resisted as contested socio-materialities. From the above-mentioned environmental justice struggles and socio-material governance arenas, it follows that rivers are actively co-produced hydrosocial territories that embody worldviews, knowledge frames, cultural patterns and power relationships (Boelens et al. Citation2016). Different agents imagine and seek to construct these riverine territories with different – sometimes opposing – values, meanings, and functions. Rivers therefore constitute political geographies of contested socionatural imagination, configuration, and materialization: dynamically produced among divergent actors in different locations who collaborate and compete over the world-that-is and that-should-be. This means that ‘rivers’ are not external to society but dynamically embody its contradictions and struggles. Examining how river territories – technical-politically and cultural-symbolically – are being shaped and transformed gives profound insight into who designs, controls, and has the power to produce what kind of hydro-social territory or river-nature (Rogers and Crow-Miller Citation2017; Götz and Middleton Citation2020).

Herein, the NWJMs have a fundamental, potentially transformative role. As transdisciplinary, multi-actor and translocal coalitions, they challenge hydrocracies’ expert paradigms to claim riverine environmental justice. Traveling and networking across hydrosocial territories, they interconnect a multitude of strategies and practices to restore or defend ‘living rivers’. They dynamically give substance and weight to environmental justice frames while spreading ‘horizontally and vertically’: through horizontal networking, diffusion, reproduction and contextualization they enlace numerous grassroots river commons, and through vertical integration and interscalar extension they interlink riverine grassroots to regional and global water and climate justice coalitions, and vice versa (see e.g. Khagram Citation2004; Borras Citation2010, Citation2016; Oslender Citation2016; Johnston Citation2018; Temper Citation2019).

While having strong transformative potential, it is fundamental to evade idealized conceptualizations of transnational river commoning movements as the post-capitalist and post-hegemonic ‘Others’ (e.g. Cumbers, Routledge, and Nativel Citation2008; De Angelis Citation2012; Dupuits Citation2019). They perform inside capitalist structures and fissures to defend the commons, usually as hybrid assemblages joining private, public, and community-based actors, knowledges, and practices. Multiscalar endeavors to defend local commons unavoidably also generate tensions regarding exclusion, legitimacy, and autonomy: locally diverse claims and worldviews risk distortion during scalar translation processes. This also calls for breaking with binary dualities between formal/customary, local/global, state/community, or expert/indigenous knowledge, and rather ‘seeing how claims, norms and rights are co-produced in transnationalization and localization processes, always in contexts of unequal power relationships’ (Dupuits et al. Citation2020, 8). To actually materialize their assembling and re-configurative potential as nature–society transformative forces, the challenge for NWJMs is to avoid falling into scalar disconnections (i.e. mis-representing grassroots) and/or falling prey to mainstream-institutionalized co-option (i.e. neoliberal commensuration). Cooperatively negotiated ‘checks and balances’ and self-critical reflections that proactively work on on-the-ground antagonisms and pluralistic feedback mechanisms is vital (Mouffe Citation2005; Cumbers, Routledge, and Nativel Citation2008; Dupuits et al. Citation2020).

4. Interconnected ontological windows for understanding socionatural river commons and bridging water justice struggles

The above conceptualizations of socionatural (river) commons, water justice, and hydrosocial territories potentially support theorization and claim-making for alternatives and express the (always disputed) material-political-symbolic crafting process of rivers and riverhoods. This paper uses these to lay groundwork for an engaged academic/action-research framework that facilitates studying, conceptualizing and supporting emerging water justice movements and their often-inventive institutions, strategies and practices to dynamize riverhoods and revitalize rivers. This framework foregrounds an understanding of river complexes (their concrete empirical manifestations and conceptual angles) in terms of four relational and interrelated ontologies: river-as-ecosociety; river-as-territory; river-as-subject; and river-as-movement. For this, we define ontology as a set of concepts and categories that help us to identify, assemble, order and explain particular entities: their nature and properties, the relations among the constituting parts, and the relationships that give them substance and meaning in their contexts.

4.1. River-as-ecosociety

The ‘river-as-ecosociety’ ontology refers to how river complexes are configured as socionatural systems by local hydrology, ecology, climates and human cultures across space and time scales. This ontological perspective examines and challenges the gaps in those sciences (ecological, sociological, hydraulic, planning, economic) and ‘development’ approaches that, from mono-disciplinary or top-down perspectives, have reduced socionatural river configurations to biological parameters, moldable hydraulics, economic metrics or productivist natural resources. The ontology examines the constitution and functioning of riverine socionatures as a result of the interplay of diverse ecosystems and human actors. It focuses on river basins, catchment areas, wetlands and hydrological cycles as mediated by climatic and ecological forces as well as by human thoughts, behaviors and technological and institutional interferences (Buijse et al. Citation2002; Wantzen et al. Citation2016). This may also include ‘underworld’ and ‘atmospheric’ rivers, that often spatially and ecologically entwine with surface-flowing rivers, rainforests, deserts –in biophysical, territorial and cosmological realities (see Boelens Citation2014; Jackson and Head Citation2021).Footnote2 The prominent use of hydrological models (e.g. Melsen et al. Citation2018) and the installation of infrastructures (dams, sluices, diversion structures, ecological flow mediators, fish migration ladders, flooding areas, etc.) receive crucial scrutiny. Also, critical currents in fluvial geomorphology and aquatic ecology emphasize the need to live with variability, complexity, and uncertainty in river governance, recognizing that interactions in river systems are dependent on local rhythms and histories of adjustment (Brierley et al. Citation2019; Scheffer and Van Nes Citation2018) (see Box 4).

BOX 4: River culture at the River Rhine: human-river-relation dialectics.

Riverine landscapes are the dynamic, constantly changing products of non-human and human biota’s interactive strategies. The ‘river culture’ notion includes elements that range from biophysical phenomena (e.g. the fertilizing effects of floods) to diversified coping and livelihood strategies along the river, to spiritual relationships (Wantzen et al. Citation2016). With increasing industrialization, such evolving biocultural diversities have been eroded by technological simplification of rivers’ flow regimes, water quality deterioration and the loss of habitats. Human/non-human adaptive traits and cultural practices that had entwined with riverine rhythms over millennia often have become obsolete. For instance, the Rhine in Central Europe (Cioc Citation2002; Wantzen et al. Citation2021, Citation2022) has been worshipped for its floodplain fertility and feared for its floods. People have established rules according to the type and prospective yields of fish since the tenth century. Along with the Danube, to which it is hydrologically connected, the Rhine forms a conveyor belt for cultural arrangements and biological species crossing Europe from West to East. Ideas like Humanism or Storm and Stress travelled along the river in the minds of Erasmus of Rotterdam or Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and its dramatic landscapes inspired the development of Romanticism in the nineteenth century. The ‘correction’ of the Upper Rhine valley reduced the dynamic, inter-connecting and meandering floodplain to a single channel, which was partially bypassed by the Grand Canal d’Alsace in the early twentieth century. The 1980s’ dramatic chemical accidents as in Switzerland acted as wake-up calls to implement collective treaties among all riparian societies. Apart from persistent pollutants, the river’s ecosystems have considerably improved although structural river morphology changes remain. Many river-culture forms have been lost but new forms of ‘living with the river’ and ‘senses of place’ are arising.

The river-as-ecosociety ontology draws attention to how rivers are co-evolutionary socionatural systems (Norgaard Citation1994), whereby both the meaning and the manner of entwining the ‘social’ and the ‘natural’ are fields of contestation. For instance, the recent environmentalist dam-removal movements tend to have different notions of ‘nature’ and ‘natural river-flow’ than local farmers’/irrigators’ collectives (that may claim dams-for-irrigation) or identity-based village heritage coalitions. Agrarian and ecological movements often diverge, converge, and entangle in multiple ways, at different time and spatial scales (Hommes Citation2022). In the Rio Grande (Malaga, Spain) farmers and environmentalists successfully united in their struggle against large dams transferring water to capitalist tourist-resorts, but farmers (in coalition with village-culture coalitions) wanted to maintain ancient Moorish-time dams for subsistence irrigation, challenging environmentalists who strove for a free-running river (Duarte-Abadía et al. Citation2019).

This ontology gives focus to how grassroots and ecological commons complexly produce their environment, often in conflict with extractive industries and hydrocracies. In this arena, water also actively moves, networks and erases. It connects riverine places and spaces, transforms living and livelihood production environments, and entwines river ecologies and societies, in myriad ways. This also colors a particular feature of river commons and movements as ‘convergence spaces’ (Cumbers, Routledge, and Nativel Citation2008) and ‘geographies of responsibility’ (Massey Citation2004), connecting distant people with each other, and people with ecologies, in profoundly material and social ways.

4.2. River-as-territory

The ‘river-as-territory’ ontology seeks to grasp the socio-territorial dynamics of rivers through understanding how different actors imagine river systems as socionatural territorial complexes and materialize their wished-for ‘hydrosocial territories’. It aims to identify and examine the complex interactions, conflicts and hybrid arrangements among dominant and alternative imaginaries and materialized river-territorial configurations. From this perspective it is critical to scrutinize hydrocracies’ river-system-shaping endeavors as territorial control projects: positioning and aligning humans, nature, thinking, feeling and action within hydro-social networks that aim to transform the diverse socionatural river worlds into dominant/dominated river governance systems (e.g. the watershed or river basin as a ‘natural’ unit of management). These territorial control projects seek to erase or alter vernacular socionatural relationships and implant new meanings, values, distribution patterns and rule-making (Baletti Citation2012; Hommes, Boelens, and Maat Citation2016; Swyngedouw and Boelens Citation2018). The focus is on how river intervention designs include precise norms as to how water should be distributed and controlled, how humans and nature must be ordered in technical scales and political hierarchies, as if these were entirely natural (Foucault Citation2007). Moral and symbolic orders legitimize this patterning. This deeply impacts the distributional, cultural, political, and socio-ecological justice domains. It includes a focus on how, in river designs, plans, and projects, river-hydraulic technology is ‘moralized’ (Latour Citation2002; Bijker Citation2007; Shah and Boelens Citation2021) as it inevitably bears the designers’ class, gender- and cultural norms. River infrastructure performs as political technologies (Winner Citation1980). As ‘hardened morality’ or ‘materialized power’ it enforces inclusion and exclusion, and particular organization and ethical behavior (Pfaffenberger Citation1988). This ontology includes zooming in on hydraulic infrastructure’s political norms and social morals, rendered invisible by modern discourse (as ‘just’ material tools) (Aubriot et al. Citation2017; Crow-Miller, Webber, and Rogers Citation2017; Rogers and Wang Citation2020).

In addition, this ontological perspective investigates how NWJMs re-organize, counter-produce and ‘re-moralize’ river territories: how they envision and produce territorial alternatives and counter-designs (Dajani and Mason Citation2018; Rocha-Lopez et al. Citation2019) (see Box 5). NWJMs challenge leading definitions and arrangements at each of the above-mentioned four echelons that produce dominant riverine territories: material assets and distribution; rules and rights; authority and legitimacy; and discourses and worldviews. Rivers as contested hydrosocial territories are not only actively networked spaces entwining nature, technology, and society at micro-meso-macro scales but also hybrid orderings that follow the workings of power and produce ‘territorial pluralism’ (Hoogesteger et al. Citation2016).

BOX 5: Decolonizing rivers and territorial orders in Canada.

Canada emerged from the Second World War as a hydroelectric superpower; only the United States generated more hydroelectricity and only Norway generated more per capita. Indigenous peoples throughout Canada were negatively affected by dams and flooding, which displaced many communities from their traditional territories and devastated fisheries and game (although, due to colonial ‘hydraulic imperialism’, these impacts have not been fully documented). Environmental review was generally lacking, as the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act was only passed in 1992. In some cases, decades passed before displaced Indigenous communities were granted some measure of rights, recognition, and/or reparations; in other cases, restorative justice still awaits.

Indigenous scholars and communities have actively resisted hydropower development and other forms of hydraulic imperialism through high-profile political protest and legal challenges (e.g. Coon-Come Citation1991). Indigenous scholars have documented their water laws that predate the colonial settler state, and assert their contemporary territorial sovereignty. This resurgence of Indigenous law has begun reshaping the legal and territorial landscape in Canada (Borrows Citation2010; Napoleon Citation2013). Indigenous knowledge systems have been incorporated into collaborative governance models across Canada, although this presents complex challenges in light of unresolved questions of sovereignty and colonialism (McGregor Citation2014). Indigenous scholars have also offered their own political-cultural normative and methodological perspectives as a means of (re)building water governance through territory-centered sociolegal traditions (Craft and King Citation2021). While acknowledging huge diversity, many Indigenous communities share worldviews, water knowledge, territorial rules and governance forms that are distinct from modernist-legalist concepts; this creates both new possibilities and tensions with decolonizing water agendas.

4.3. River-as-subject

The river-as-subject ontology revolves around questions of subject-production in the realm of riverhoods. It directs our attention to scrutinizing how both subject-making and claims to be considered as a subject (claims to ‘subject-hood’) form part of struggles around river commons – central to socioterritorial governance, but often omitted in water/environmental sciences approaches (see Box 6). Several NWJMs proliferate concepts and proposals for action related to ‘sentient rivers’ and ‘rights-of-rivers’, among many, which foreground essential questions: Who/what is (or is not) a human/non-human subject? On what conditions and with which (socio-ecological, ontological, epistemological and cultural-political) results? Who defines this? Therefore, our river-as-subject ontology focuses on the nature of rivers’ being (human/non-human), and the concepts and categories that diverse actors deploy to express these ‘riverhoods’.

BOX 6: Attaching to rivers.

The river-as-subject ontology does not only call for scrutinizing how, why and with which effects rivers are approached as subjects. It also provides the invitation to reconsider researchers, activists and other concerned members of society as ‘river subjects’ – part of river commoning struggles. One way to do so is to understand the river as a Möbius band, in which the river, societal and non-human actors, and politics, co-constitute each other. A socio-ecological river expresses being/becoming subject through the meaning ascribed to it, which in turn shapes the river and those ascribing the meaning at the same time: as entwined social/natural communities. This attribution of meaning, as we describe in other sections, is a highly contested process that turns the Möbius river in one or the other direction. To grasp this fluidity and co-constitution, it is vital that researchers and activists do not place themselves in any way above or even below the river, but within its ebb and flow and the very practices of doing and being with a river. In terms of research (and activist) practice, this then means attaching to rivers and becoming-river, looking sideways at the river, going along with its flow and attuning to how it relates to everything else, materially, socially, politically. A river thereby turns from being a noun into being a verb, opening the possibility to engage with its on-goingness, rhythms and processes of mutual subject formation. For engaged researchers, the question that need to be posed then becomes how we see ourselves and how we engage with the river as simultaneously ecological, social, moral and political beings: as subjects who seek to make critical political-ecological choices and actions – beyond any reification or essentialization of nature, culture, or cosmos. It is only from there that critical research, social mobilization and responsibilities can be enacted through attaching to the river and becoming-river – in ways that inherently challenge earlier modernist ways of understanding and living rivers. Therein, ‘attunement’ becomes the operational word as opposed to ‘ownership’, along with creative alertness, care, reciprocity, solidarity and responsiveness (Huijbens Citation2021) ().

In the river-as-subject ontology two key aspects are interwoven. First, our political ecology lens highlights how water governance not only deals with producing socionatural order via the control of infrastructure, investments and knowledge but also strives to shape subjects (humans and nature) to be governed. In other words, hydrocracies ontologically, normatively, and materially construct and align both river objects and subjects (Mills-Novoa et al. Citation2020). As Mosse (Citation2008, 945) puts it ‘State water projects have been central to the creation of colonial subjects, the formation of citizens in nation-building projects, or the production of a consumer-citizenry under the current neoliberal commoditization and privatization of water’. In response to local riverhoods (seen as incomprehensible, irrational, unruly, disordered), governmentalization seeks to align subjects’ identification and worldviews with the dominant water culture (Foucault Citation1982; Dean Citation1999). These processes of subject-making apply not just to social communities but equally to ecological communities – or rather, to both simultaneously.

Second, affected communities react to and challenge these processes of subject-shaping and socioterritorial ordering through claiming voice and self-determined identities and rights as subjects (Burdon Citation2011; Descola Citation2013; Boelens et al. Citation2021). NWJMs support this and claim that climate change or local river pollution challenges can only be confronted through a radically different relationship with rivers that considers them as equal subjects – from nature as an object of law and human possession to a being that is a moral, legal and political subject and that horizontally entwines with human lives (Yates, Harris, and Wilson Citation2017; Strang Citation2020; Reyes-Escate et al. Citation2022). Some river commons approach rivers as sentient transformative agents (Ulloa Citation2020b). Also, rights-of-rivers approaches have gained broad attention (Kauffman and Martin Citation2018; Roth Citation2020; International Rivers Citation2021), acknowledging that ‘nature in all its life forms has the right to exist, persist and regenerate its vital cycle’ (GARN Citation2020) (see Box 7).Footnote3

BOX 7: Mobilizing for rights of rivers in New Zealand and Australia.

Rivers have been constructed as rights-bearing subjects in legal decisions in Aotearoa (New Zealand), and aquatic environments have been conferred similar status in Australia’s market-based water allocation system. O’Donnell (Citation2018, 4) attributes the prevalence of rights of rivers to ‘the intersection of two very different legal trends in environmental law: Earth jurisprudence, and the use of market mechanisms to achieve environmental outcomes’. Recognition policies of the settler-colonial state (Jackson Citation2018) have also contributed, particularly in Aotearoa, when in 2017 the Parliament acknowledged the relational values and ontologies of Maori by conferring the Whanganui River as a subject of rights. A new legal entity was established as guardian of the entire river, thereby ‘reasserting a founding place for tikanga Māori (Māori law) to once again guide regional natural resource governance’ (Ruru Citation2018). The settlement, however, largely operates within the parameters of the British/Western legal model and its rights notions (Charpleix Citation2018): existing private property rights in the river remain unaffected and consent is not required for the use of water from the river or its tributaries.

Australia has not seen similar rights-of-rivers case law, but the environment’s right to water (to an environmental flow) has been legally recognized since the 1990s: the environment is a new water user under legal instruments designed to meet ecological imperatives. A large scientific practice resulted, to establish ‘environmental flows’ as a priority water use (Arthington et al. Citation2018) and (in the context of the world’s largest water market) new actors – referred to as ‘environmental water holders’ – have proliferated. They buy back water to restore the health of rivers, wetlands, and floodplains (O’Donnell Citation2018). At the same time, in opposing state-based water allocation and techno-managerial determination of ‘water requirements’ of rivers (Jackson Citation2017), indigenous peoples are claiming their rights to govern rivers. In doing so they unsettle dominant river ontologies. In the south, they seek to leverage water allocations off the success of the environmental flow concept – strategically demanding cultural flows that would entitle them to control water under a separate indigenous use category. In a significant case relating to the Martuwarra (Fitzroy) River in the country’s tropical north, where most rivers run free, indigenous leaders are pursuing recognition of that river as ancestral person with a right to life and flow. This novel and intersectional category of legal personhood aims to bridge colonial and First Law (Martuwarra RiverOfLife et al. Citation2021).

More important than the (ambivalent) legal-institutionalized figureFootnote4 is to see how in myriad ways river-as-subject notions are, and work out as, the cultural-political result of broad societal alliances. In Ecuador, for instance, this took the form of an epistemic pact among non-indigenous and indigenous population sectors who creatively merged local, national and global norms, symbols and concepts for the defense of nature and territory (Valladares and Boelens Citation2017). River-as-subject understandings, therefore, are highly mobile and sprout at various sites and scales: ‘yet not as a universal, frictionless form; instead [they] are translated into various political, cultural, geographical, and even ontological milieux’ (Kinkaid Citation2019, 559). Therefore, river-as-subject notions travel between, and are translated into, local and translocal spaces of meaning-making and governance.

In complex everyday realities, socionature river commons – intertwined social and ecological collectives – claim voice and rights as agents and subjects. Their demands relate to the layered water justice domains: both marginalized human groups and nature require re-distribution, both ask for recognition as subjects not objects, both demand fair political voice and representation, and both require socio-ecological health and flourishing – now and for the worlds to come.

In this political process it becomes crucial to understand how, why and with what effects rivers, as socionatural systems, are approached as subjects – not only in terms of rivers being seen and experienced as subjects but also in how they are politically shaped into being as empowering or disempowering subjects (e.g. Arguedas Citation1964; Li Citation2013; Dukpa et al. Citation2019; Valladares and Boelens Citation2019). In fact, both marginal and dominant human groups seek to appropriate the moral agency of more-than-human rivers in cosmopolitical arenas (Ingold Citation2000; Stengers Citation2010).

Consequently, river-as-subject understandings and approaches do not and cannot guarantee any inherent decolonization promise or emancipating benefit. They too are mediated by unequal powers and struggles, for instance over the installation of guardianship and regarding how they are subject to legal, political, economic and moral-normalizing interests in everyday battlefields. It is therefore key to pay attention to on-the-ground embedded practices and politics, beyond romanticization or glorification of indigenous and grassroots action (Grande Citation1999; Swyngedouw Citation2011; Li Citation2013; Whatmore Citation2013).

4.4. River-as-movement

The ontological perspective of ‘river-as-movement’ focuses on comprehending the notions and practices supporting strategies of cross-cultural, trans-scalar water justice movements to produce disruptive and emancipating riverhoods by articulating experiences, views, instruments and strategies across contexts. It focuses on the relationality of NWJMs, supporting and transforming (co-)governance of river commons – how they connect local to global and thereby involve sidelined actors and alternative river wisdoms (see also Edelman Citation2009; Kauffman Citation2017; Vos et al. Citation2020) (see Box 8). This river ontology looks at demands, strategies and practices of interlinking and co-learning among complementing agents to bring about paradigm shifts and influence socio-environmental justice.

BOX 8: Anti-dam and alter-dam movements in India.

A ‘million revolts’ have been unfolding over dams in India since the colonial times. The movement against the Sardar Sarovar Project on the River Narmada is the most celebrated anti-dam movement in India, having forced the World Bank to withdraw from the project. Anti-dam movements in India have been characterized as human rights movements (the human ‘right to life and livelihoods’ is under threat), as indigenous people’s movements (about 40 percent of the people displaced are indigenous), and as environmental movements (attempting to re-define human–nature relationships) (Cortesi and Joy Citation2021). Since the Uttarakhand High Court verdict in 2018 that the Indian rivers Ganga and Yamuna, their tributaries, glaciers and catchment areas have rights as a ‘juristic/legal person/living entity’, rights-of-rivers has also entered the lexicon of anti-dam movements, in complex local–global interactions (Joy et al. Citation2018; Shah et al. Citation2019).

Since India has many transboundary river systems, their damming brings in transboundary ramifications and large political controversies. These projects have resulted in reduced flows, impacted sediment dispersal and exacerbated pollution for downstream nations. The mega ‘Inter-linking of Rivers Project’ is a new imagination of the Indian ruling classes to tame the rivers and solve all water problems – both droughts and floods – by transferring water from the ‘surplus’ basins to the ‘deficit’ basins. This involves extensive damming of rivers, with huge social and ecological costs. India’s neighboring countries are apprehensive of the impacts this gigantic project can have on them. The Indian water sector is still driven by the hydraulic mission that combines scientism, an anthropocentric domination-of-nature ideology and technology as cure-all. Large dams and capitalist irrigation schemes are the outcomes of this approach (Molle, Mollinga, and Wester Citation2009): water flowing to the sea is a waste. But functionalizing every drop of water for human use leads to maximum abstraction of water from the rivers. Therefore, with regional and global allies, anti- and alter-dam movements in India creatively struggle for alternatives, traversing the diverse politico-economic, technical-engineering and symbolic-discursive battlefields of environmental justice.

River movements’ struggles need to be considered multi-dimensional and polyvalent. Demands for distributive equality combine with demands for the right to be different: socializing water benefits, democratizing authority and claiming recognition of pluralistic cultural-normative orders. Many NWJMs struggle for enlivening river commons on the edges of ecological, civil and political society, impacting modes of government/being-governed (Joy et al. Citation2018; Hidalgo-Bastidas and Boelens Citation2019; Villamayor-Tomas et al. Citation2022). Therefore, first, the ontology focuses on identifying and understanding NWJMs’ (self-)definition of water norms and rules, nature values, territorial meanings and governance forms.

Second, NWJMs take diverse forms (of organizing, mobilizing, acting) and they do so across different scales. Next to ‘horizontal peer-to-peer networking’ to broaden the movement across river geographies, they also engage in ‘vertical networking’, e-activism and diverse forms of virtual, artist and cultural commons (De Angelis Citation2012; Hernández-Mora et al. Citation2015). The transnational character of river domestication, commodification and pollution means that local river collectives re-scale their struggles in flexible larger networks, thereby challenging the ‘manageable scales’ to which they are confined by formal water bureaucracy (Cumbers, Routledge, and Nativel Citation2008; Swyngedouw Citation2009; Martínez-Alier et al. Citation2016).

Third, the ontology triggers inquiry and conceptualization of how movements – traveling back and forth across riverine places and scales, embedding local in global and global in local – interpret, support and hybridize riverhood ontologies and strategies, contesting the neoliberalization of river systems to defend/shape the multi-scale integrity of socionatural territories (Yates, Harris, and Wilson Citation2017; Latour et al. Citation2018). Thereby, their ‘rooting’ (Vos et al. Citation2020) is key: ‘it is only when relationality connects to absolute spaces and times of material and social life that politics comes alive’ (Harvey Citation2006, 293; see also Cumbers, Routledge, and Nativel Citation2008).

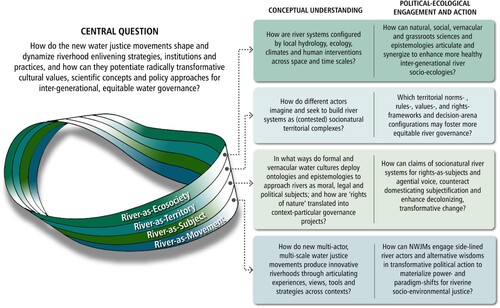

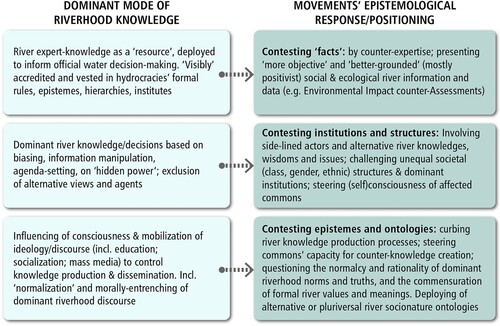

Fourth, the creation and mobilization of alternative riverine knowledges is central in NWJM’s constitution, identity and strategies (Duarte-Abadía et al. Citation2019; Fox and Sneddon Citation2019). Some key epistemological responses to dominant riverhood knowledge that we have observed are presented in .

Figure 2. Movements’ epistemological responses to river domestication knowledge (authors’ own elaboration).

This indicates how movements’ strategies go beyond just reactive responses to dominant forces (‘power-over’). Rather, they are pro-active. Movements draw on forms of ‘power-with’ (binding in solidarity, multi-actor alliances and cross-cultural assemblages); ‘power-to’ (based on creative skills and capabilities to shape), and ‘power-within’ (based on inner strength, self-confidence, identity and mutual belonging) (e.g. Moffat et al. Citation1991; Escobar Citation2001; Nicholls, Miller, and Beaumont Citation2013) (see Box 9). In this river-as-movement ontology, the focus is on how these transformative forces combine, and how they manifest in ‘epistemic pacts’ among different, complementary agents such as grassroots, academic, activist and policy agents, aligning with non-human river ecologies and across different action-arenas (e.g. Latour et al. Citation2018; Shah et al. Citation2019; Shi et al. Citation2021). The ontology thus opens a perspective on how movements, through critical and creative integration of heterogeneity, translate and articulate a plurality of experiences, views, knowledges, tools and strategies, moving humans and non-humans who along the road craft their collective political identities, to engender and re-make river commons, river territories, and riverhoods.

BOX 9: Spain’s movement for a new water culture: from e-flow policies to multiscalar environmental justice movements.

Throughout the twentieth century, Spanish water policy served the dominant ‘hydraulic mission’ (Saurí and Del Moral Citation2001), a socio-political, economic and discursive endeavor aiming to achieve the country’s socio-economic transformation through water development. This effort was led by a dominant water-policy community made up of its material beneficiaries – large-scale irrigation, hydropower, construction companies – and some public agents as civil engineers. With the advent of democracy in the 1970s/1980s, new voices and opposing actors emerged – regional governments, environmental groups, local movements affected by proposed waterworks, engaged academics, and some political parties. The opposition coalesced around the ideas of the ‘new water culture movement’, an epistemic community (Bukowski Citation2017) of activists, academics and local alliances that offered an alternative water management paradigm for Spain. This community, developed around a new understanding of river –society relationships, aimed at ecological conservation, transparent participatory decision-making, and a socially fair economic rationality in policymaking. Starting in the early 2000s, and coinciding with the implementation of the EU Water Framework Directive in Spain, these actors organized into networks in river basins or at a regional scale (Hernández-Mora et al. Citation2015). They aptly criticized ‘old wine in new bottles’, such as the expertocratization of dam removals and river restoration projects, and the translation of environmental river flows into technified ‘e-flows’: ecological demands that were appropriated and reinterpreted by the dominant techno-cultural management discourses. Currently, these river-based networks engage with and contest dominant water truth regimes. Their struggle encompasses and interrelates the ‘four echelons’ mentioned above (section 3.2) – material assets and distribution; rules and rights; authority and legitimacy – all grounded in the desire to challenge dominant discourses. They understand water as common patrimony, with implications on basic notions of rights, equity and environmental justice. They engage both horizontally with other networks, sharing arguments, strategies, knowledge and goals; and vertically with other organizations and actors that contribute to build their alternative worldview.

Our four-ontologies framework (see ) enables identifying, understanding and conceptualizing how socio-ecological river commons move across contexts, cultures and scales. The ontologies are closely related and complementary. In terms of the Möbius-band metaphor (with its unceasing, incremental knowledge spirals), if the river is travelled at ‘full length’ we would traverse and embrace all transdisciplinary perspectives without ever crossing an edge or boundary that divides the river’s socionature ontologies. They interact, shape and constitute each other, and enable us to understand differences and synergies between them at different time and geographic scales.

5. Discussion: transdisciplinary knowledge co-creation and multiscalar action for riverine environmental justice

Rivers are intense sites of struggle. The fate of rivers has long preoccupied advocates of modernity. While for many, mega-dams have been the quintessential symbol of things modern – witness Nehru’s famous dictum that ‘dams are the temples of modern India’ – for others, they symbolize Man’s instrumental rationality at its worst. From India’s gigantic Interlinking-of-Rivers Project to China’s Three Gorges Dam, to Brasilia’s Belomonte, to the megalomaniac river-works in Africa that enable multi-million-hectare-water-grabbing: MasterMind river-hydraulic utopias turn out to be everyday dystopias (Boelens Citation2017). It is no wonder that domesticating rivers leads to so much conflict, summoning an entire political ecology of fierce contention. Mobilizations in defense of rivers can be viewed as instances of political-economic, ontological and epistemological conflict and resistance. Some inter-community coalitions defend against extractive river-interventions to reclaim their land and water property rights, livelihoods or territory; others state that they are one with the river. Others consider the river as a living sentient being. In contrast, a modernist ontological perspective frames a river as a body of H2O, a geomorphological phenomenon whose potential should be productively harnessed for human ends. Considering that rivers are ontologically complex entities, environmental conflicts, thus, are simultaneously ontological conflicts as they gather multiple beings into existence (Escobar Citation2018). When conflict centered on rivers arise, the question becomes, are alliances across ‘ways of worlding’ possible or are they fundamentally incompatible? (see Box 10)

BOX 10: Riverhood as epistemic interface.

Joining innumerable companions, for Luz Enith, a young Afrodescendant environmental engineer and activist, Colombia’s Atrato River struggle rests on the notion that ‘We need to defend the river we all are’. The Atrato, recognized as ‘subject of rights’ in 2016, emerges from these movements as a relational entanglement, only partly understandable to the modernist state. ‘We are all the Atrato’ simply cannot be in the ontological eyes of the state, since it ineluctably separates ‘humans’ from ‘river’ and ‘individual’ from ‘community’. Moreover, a community that involves more-than-humans is unthinkable. At best, states can treat rivers as juridical subjects. Myriad riverhood notions thus function as epistemic interfaces that enable that which cannot be to emerge in politics. Such politics enable confronting and tensely entwining diverse ways of ‘worlding’ – one stemming from the inseparability between river, territory and humans, and another that cannot but dwell on their separation. In these ontological interfaces, what is uncommon to both worlds meets through the mediation of NWJMs’ discourses and practices. Epistemic interfaces are disruptive, creative, and complex. They may involve disagreements over incompatible ontologies (Duarte-Abadía et al. Citation2020; De la Cadena and Escobar Citation2022), or caution for ‘equivocal translations’ or misleading ‘common’ referents (Viveiros de Castro Citation2004; Blaser Citation2016), and they may present openings for new epistemic pacts among the diverse (e.g. Martínez and Acosta Citation2017; Valladares and Boelens Citation2017). Sharing river-ontological referents, moreover, is not a prerequisite for shared river struggles and transdisciplinary environmental justice pacts: accepting difference-in-unity, as a point of departure. Being one with the river exceeds both standardizing ‘forced engagements’ and the modernist-dualist ontology separating the social and the natural, humans from non-humans. They interrupt the coloniality of practices that purport to make the world one, and hint at unknown forms of togetherness (Escobar Citation2018, Citation2020).