ABSTRACT

Environmental and agrarian changes are proceeding rapidly in southern Belize. Despite common recognition of these changes, little research has attempted to examine the class processes involved in social and environmental change. We trace how capitalism has transformed household reproduction over the past four decades, focusing on two key pathways by which these changes unfold: the commercialization of land use and the education of the labour force. Emerging class processes in the Maya communities undermine subsistence agriculture, generate inequality between households and genders, and magnify conflicts over land. These effects complicate struggles for communal land rights and class solidarity.

1. Introduction

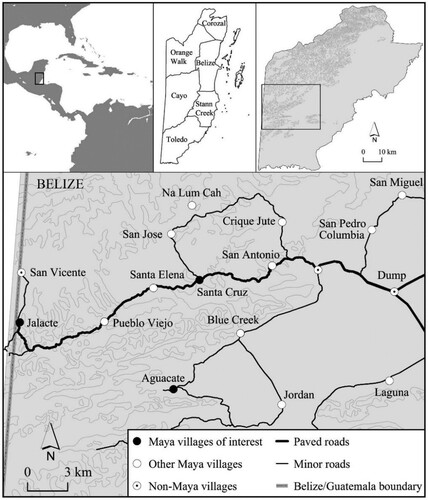

In varied ways, scholars of agrarian change have sought to explain how rural class processes relate to forms of social difference (e.g. race, ethnos, nation, gender, geography, and religion). Such inquiry is inherent to peasant studies since the subject-position of the peasant is class-like and class-relevant but not itself a class. The political importance of these complex inter-relations of class and social difference in peasant communities were emphasized by Marx (Citation1852), Lenin (Citation[1899] 1964), Gramsci (Citation[1926] 2000), and Mao Citation([1927] 1965). Subsequent research has analysed the global unfolding of capitalism and its novel variations in class processes and agrarian relations.Footnote1 Here, we extend this literature to the rural villages of the Toledo District in southern Belize, where the residents of thirty-nine villages may be characterized in two distinct ways.

The first emphasizes class. In this view, the people of rural Toledo are peasants, marginal producers whose livelihoods are rooted in the milpa and who undergo proletarianization at uneven rates.Footnote2 Most are poor (NHDAC 2004, Citation2009). In 2009, about half of households in Toledo fell below the poverty line and 37.5% were labelled ‘indigent’ (unable to meet basic needs), higher than any other District (NHDAC Citation2009). The most recent poverty study (SIB Citation2021a) found that Toledo’s poverty rate had increased to 82%, significantly higher than Belize as a whole, at 52%. While these studies do not distinguish between rural and urban areas, poverty is deepest in the rural villages. Concrete floors, electricity, piped water, books, computers, educational attainment, and healthcare provision are lowest among rural households in southern Belize (NHDAC Citation2010).Footnote3 The best available studies support the generalization that rural Toledo is the poorest part of Belize and one of the poorest regions of Central America.

A second approach emphasizes indigeneity. The people of rural Toledo – at least the majority who speak Q’eqchi’ and Mopan Maya as their first language – are Indigenous peoples experiencing racial discrimination, dispossession and marginalization: forms of violence rooted in colonialism. The Q’eqchi’ and Mopan are two of the three Maya linguistic communities present in Belize today, descendants of people who occupied the area prior to the dispossession, enslavement, and subjugation wrought by European imperialism. They are victims of ongoing colonial violence, rooted in racist ideology, which fails to recognize the Maya as Indigenous peoples with rights to land and distinct ways of being. From this perspective, the logging concessions granted by the Belizean state to foreign-owned logging companies without the consent of Maya communities (to use one pertinent example)Footnote4 shows that Maya forms of land ownership and land uses are not valued because they do not conform to Western conceptions of knowing and being and do not conform to capitalist interests. In this view, the villagers’ political struggles since the 1990s aim to advance the rights of the Maya as indigenous people to overcome exclusion and (in a more radical vein) to complete the decolonization of southern Belize (e.g. TMCC and TAA Citation1997; Wainwright Citation2008; Mesh Citation2017; JCS, MLA, & TAA Citation2019; Gahman, Penados, and Greenidge Citation2020).

We aim to clarify how class processes are playing out in these Maya communities. We focus especially on the production and sale of agricultural commodities and labour power outside of the villages. These processes, we argue, have stressed household reproduction strategies involving milpa agricultureFootnote5, resulting in adaptations. To argue for the necessity of attention to these class dynamics is in no way to deny the indigeneity of the Maya people or the legitimacy of indigenous land claims. Rather, we aim to clarify how class processes contribute to agrarian change in southern Belize today (for a general framework: Bernstein Citation2010). Such an analysis, we hope, will also clarify how the deepening of capitalist social relations in the countryside contributes to the marginalization and exploitation of Maya peoples in the region.

Because the household is the unit through which labour and energy are organized in rural societies, it remains a vital object of analysis for understanding agrarian change. Anthropologist Rick Wilk’s research into household economy in rural Toledo provides a source of inspiration and baseline for our work: our description of household economy is intended to update his findings from four decades ago. Wilk’s ([Citation1991]Citation1997) Household Ecology characterizes the organization of households in rural Toledo in scrupulous detail. At the time of fieldwork in the late 1970s, domestic economy in Maya communities entailed a balancing act of labour reproduction and application toward subsistence farming, rearing livestock, hunting, foraging, and periodical travel to the coast to sell farm products and purchase consumer goods. While Wilk’s and numerous other studiesFootnote6 remain useful, these dynamics warrant re-evaluation.

Unlike Wilk’s, our framework is built upon the insights of Marxist studies of agrarian change. In the second chapter of Household Ecology, Wilk dismisses Marxism as ‘a nineteenth-century view that casts capitalism as the ultimate culprit’ ([Citation1991]Citation1997, 26) and that belittles ‘anything that came before capitalism (or survives alongside it) [as] so completely different … that it has no relevance’ (24). These generalizations do not hold. One of the major accomplishments of the Marxist literature in agrarian studies has been to show that the forms of exchange, land use and livelihood that pre-date the emergence of capitalist social relations in the countryside shape the path of change. While the general tendency is for capitalism to incorporate people into the global market for commodity exchange (including land and labour power), the particular ways this unfolds, and the specific local outcomes, are contingent upon the social and geographical particularities that shape the incorporation of rural communities into capitalist modernity.Footnote7 To draw upon Marxist concepts to examine how capitalism transforms rural, indigenous communities is not to adopt a nineteenth-century fashion, but to try to grasp the present by accounting for the historical processes and forms of class struggle that constitute it.

This paper contributes to this project by analysing the class processes of household reproduction and land use in southern Belize from 1981, when Belize won formal political independence from Great Britain, to 2020, when the covid pandemic brought major social and economic disruption. We ask: how do rural Maya households reproduce the conditions for their existence today? How do class processes drive land use and agroecological changes that are presently unfolding across southern Belize? We argue that class processes – particularly involving household reproduction of labour power – are driving changes in land use to the detriment of the customary milpa. These novel land uses, plus the out-migration of young people for education and wage work, are changing demographic patterns and reinforcing class stratification in the villages. These socio-economic changes are complicating the struggle for and future of communal lands.

To develop these claims, we present a model of household reproduction that explains why livelihood patterns have shifted in the decades since Wilk’s (Citation1981) landmark study. Our analysis emphasizes dynamics for improving opportunities to sell labour power in Belize, particularly education and commercial farming. Original data sources include notes from years of fieldwork in rural southern BelizeFootnote8 and survey data from interviews conducted between 2016–2017 with 33 heads of households in three communities. Interviews typically lasted 90 min using a semi-structured methodology where subjects responded freely to a consistent set of questions on land use, household labour, and environmental change (see ). Key insights were transcribed verbatim and data tallied to facilitate comparisons between communities.

2. Class processes and agrarian change in southern Belize

At the time of Spanish contact in the early 1500s, the indigenous inhabitants of the region spoke Manché Ch’ol, a dialect of the Cho'lan branch of the Mayance language family.Footnote9 The Manché Ch’ol speaking people are often believed to have been fully extinguished. Nevertheless, an emerging consensus in the literature is that the Manché Ch’ol communities were not eliminated in the 1500s by slave raids and diseases nor entirely removed by the Spanish during the reducción of the 1690s.Footnote10 Some survived and became mixed with other indigenous people who moved into the area as the region’s demography rebounded from the decline of the 1500s.

Although neither the Spanish nor the British settled the region, European colonization led to changes in settlement, languages, and livelihoods as indigenous people adapted to changing conditions. During the early nineteenth century, the British sought to extend their control of the territory of the eastern seaboard of the Yucatán Peninsula: ‘British Honduras’, as the society was then known, was not yet a formal colony. Their colonial economy was based upon the plunder of the tropical hardwood forests (initially for the export of logwood, later mahogany) with enslaved African labour. When groups of enslaved workers first entered the forests of southern Belize (ca 1795–1805) – commanded by British slave-owners to cut logwood and mahogany for export – there were abundant if disparate indigenous people, probably still Manché Ch’ol-speaking but mixed with other Mayance-language speakers (certainly Mopan, probably Itzaj’ and Q’eqchi’, perhaps others). An analysis of the oldest legal record of a trial concerning southern Belize by Wainwright (Citation2021b) demonstrates that the region was populated by indigenous people in the early nineteenth century, prior to British colonization. As the region was logged (in the early nineteenth century) and came under the sway of the Catholic Church and British colonial state (toward the end of the nineteenth century), the survivors of the contact era were absorbed into predominantly Mopan – and Q’eqchi’-Maya speaking communities.Footnote11 Since the nineteenth century, these communities have engaged in a protracted and uneven process of incorporation into capitalist social relations.

2.1. The present political-economic situation

Today, each of the 39 Maya communities in southern Belize manages its own territory through a village-level form of indigenous governance known as the alcalde system.Footnote12 A movement emerged in the 1980s to defend the collective rights to their lands. Many years of political and legal struggle culminated in a Supreme Court decision securing indigenous rights of their customary lands (Conteh Citation2007). This decision was subsequently ratified in a Consent Order before Belize’s highest court, the Caribbean Court of Justice, in April 2015 (CCJ Citation2015). However, due to the intransigence of the Government of Belize, the realization of the Consent Order – which calls for the demarcation and titling of the community lands – has been slow.

By contrast, changes in household economy have unfolded more rapidly. Maya households routinely purchase and sell commodities (including labour power) which circulate in global markets. As we will explain, commodity production and household reproduction have become subsumed to capital’s drive. Yet most households have not been separated from the means of production, because most Maya villages have not completely parcelized and commodified the land.

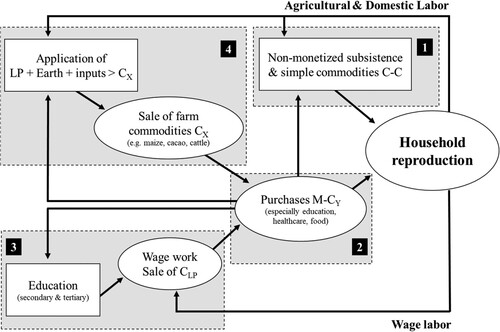

schematically represents the four components of household economic activity in contemporary rural Toledo. Households have customarily satisfied consumption needs through (1) subsistence farming activities and domestic labour, aspects of which now require monetized inputs (e.g. herbicide or soap). In capitalism, (2) purchases of consumer goods and services – primarily food, education, healthcare, transportation – command an increasing share of reproduction. Households have two principal strategies to obtain the requisite money for these purchases. They may travel outside the village to (3) sell the labour power commodity, whose value improves with higher education. Or they may (4) combine labour power, land, and purchased inputs to manufacture a limited number of commodities such as grain or meat, and sell them in competitive markets. Most Maya households in rural Toledo today engage in all four activities, albeit in uneven and heterogeneous ways. Notwithstanding this complexity, the basic principle that binds the household economy together today is that social reproduction requires the regular sale of labour power and products of labour: without cash flow, a household’s survival becomes untenable ().

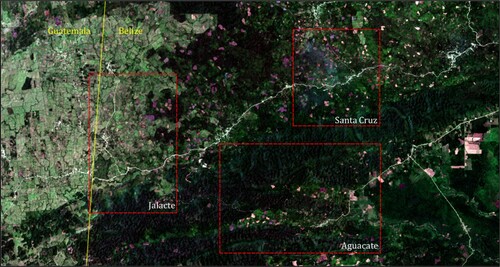

Figure 2. Map of land cover in central Toledo District. The approximate boundaries of land use of the three Maya villages discussed in the paper are marked with red rectangles.

Figure 3. Four components of household reproduction in rural Toledo. (1) Non-monetized subsistence activities include domestic labour and household production of milpa, livestock, and forestry products. Prior to capitalism, some of these products entered trade within the local-regional economy, i.e. simple commodity-commodity exchange (C-C). (2) Today, purchases with money (M-CY), especially on education, healthcare, food, and transportation, command an increasing importance within household reproduction. To obtain money, households have essentially two options: (3) sell labour power commodity (CLP), whose renumeration improves with higher education; or (4) combine labour power, land, and purchased inputs to manufacture and sell farm commodities (CX). In effect, the household economy is re-formed to the capitalist circuit of reproduction of labour power, C-M-C. The general tendency is the diminishing importance of (1), and differentiation of households according to pathways (2–4).

The milpa remains an element of social reproduction, but its logic is subordinate to the sale of labour power. Subsistence farming persists in part because milpa agriculture is low-risk and highly adaptable (Chayanov Citation1986, Wilk [Citation1991] Citation1997), especially where land is not scarce as in most villages of Toledo district. In our survey of Maya households in the study villages we found that all 33 respondents continue to farm two maize crops per year, and all but two do so using household labour plus collective labour for planting maize.

While milpa might therefore appear stable, the social and metabolic relations of smallholder agriculture have changed since the time of Wilk’s research. Perhaps the most visible shift concerns fallow length and cropping intensity. In certain areas – along the Guatemala border, roadsides, and on high fertility soils – fallow has dropped to a year or less. Accompanying land use intensification, routine activities of milpa cultivation now require significant cash overlay. This is especially true for chemical herbicides, which arrived in southern Belize in the 1980s by way of agricultural development projects. Herbicides are favoured because they save time in weeding, freeing up labour for other demands including wage work, and because they can control noxious grass weeds. But they are also expensive, requiring a day’s wages per application. 29 of 33 survey respondents reported using them 1–3 times per cropping season depending on weed competition. Another significant expense is wage labour: 12 of 33 households reported hiring labourers for cultivation and harvest. In most villages, hired workers are fellow villagers who charge a day rate of $12.50 (USD)Footnote13, whereas households along the border employ cheaper piece rate migrant labour.

While subsistence activities provide a livelihood insurance policy, imported foodstuffs command a growing share of consumption. A study by Cleary et al. (Citation2021) provides data about the dietary habits of 12 Maya families in Aguacate village. Compared to Wilk’s data from 1979, Cleary et al. found statistically significant increases in flour, rice, chicken, and pork consumption; maize consumption declined as rural people consumed a more heterogenous mix of subsistence products and store-bought foods. Such changes in household dietary patterns are connected to the expansion of a mercantile and the rural bourgeoisie. The import sector in Belize is small, shy of $1B in 2019 – and only a fraction of that trickles into the Maya villages of Toledo. Nevertheless, commodity import and distribution chains comprise an intense field of competition dominated by expatriated merchants from Guangdong, China. In contrast, the domestic sector for staple grain and meat is an uncompetitive monopoly of industrialized Mennonite farmers in the northern districts of Belize who supply most of the carbohydrates and proteins not produced in the villages by way of refrigerated trucks and village shops (Wilk Citation2006).

Apart from food, a growing ensemble of household activities are also becoming monetized. Mobility, education for the children, and access to decent health care are unobtainable today through customary livelihood; they require sums of money that few can generate through milpa production. Hence, most households now treat the milpa as an insurance policy – to ensure that basic needs are met – while maximizing opportunities to sell labour power and engage in commercial land use. Through both processes of farming and employment, the household sells commodities (C) for money (M). Money is then used to purchase commodities that reproduce household labour power (C). Household reproduction therefore enters the circuit of capital (M–C-M’) via C–M-C, the reproduction of the labour power commodity (Marx Citation[1967] 1990).

The standard local strategy for generating household income is to produce agricultural crops for sale (32 of 33 households report doing so). Farmers sell their surplus of milpa products – maize, beans, pumpkins, pigs – in the local market, either in Punta Gorda town or across the border (Santa Cruz, Guatemala). Yet received prices tend to be low; Mennonite products and imported foods out-compete traditional products in the marketplace. An alternative option is to sell grain to Guatemalan merchants, whose cattle trucks ply the Toledo countryside buying seeds at super-exploitative prices ($0.10/lb. maize). Occasionally, lucrative cash crops jive with milpa farming and present fleeting windows of opportunity. Wilk noted the ‘speed at which [Q’eqchi’] production systems change when market opportunities arise, as they have for bananas, cocoa, beans, rice, and marijuana’ throughout the 20th C ([Citation1991]Citation1997, 116).Footnote14 A more recent example is pumpkin seed: export to Guatemala boomed during the past decade after the price jumped to $1.15/lb. In our survey, 20 of 33 households attempted to cash in, seeking out their highest, most fertile forests for pumpkin monocultures. Similarly, illicit rosewood exports to China enjoyed a boom in 2013–2014 (Wainwright and Zempel Citation2018).

Growing cacao and raising beef cattle can generate larger potential profits. Producing these commodities, however, generates greater social tensions with other milperos, for they require locking up a relatively secure tract of land for a prolonged period of time (positive yields may require ten years for cacao). A cacao sector has formed in southern Belize over past four decades (Steinberg Citation2002; Emch Citation2005). 10 of 33 households reported growing cacao for market in our study; in some neighbouring villages this proportion is higher (Stanley Citation2015). Over the past decade, a cacao producer co-op dissolved, resulting in less favourable terms for small producers. Cattle farming has experienced rapid and sustained growth during the same period. As noted by Wright et al. (Citation1959), the agroecological conditions of Toledo are ideal for grass production, but until recently the infrastructure was inadequate. Road improvements have generated a cattle boom. Across Belize, the price of live cattle and the national herd size has doubled since 2006 (from $0.50/lb. to $1.00/lb. and 60k to 120k head, respectively). Pastures creep into the forests along roadway networks and the Guatemalan border such that today, a significant minority of Maya households participate: six of 33 households we interviewed reported this land use.Footnote15 Belize government agencies (the Belize Agriculture Health Authority and the Ministry of Agriculture) and Belize Livestock Producers Association provide trainings, meetings, veterinary services, and office space for cattle ranchers at the Toledo district agricultural station. Indeed, pasture expansion and cattle traceability have become top priorities for agricultural development nationwide.

3. Employment, education, and the gendered division of labour

In our survey, 16 of 33 households reported members working outside of the village. 12 of 16 held short-term, low-paying jobs in the coastal cities and plantations; the remainder held well-paying, secure employment in the government and NGO sectors. Typical roles include construction worker, agricultural labourer, security guard, military, and police. Few, if any, of these opportunities are typically available to Maya women. Only one household we surveyed reported women who held employment outside of the village. Women perform most domestic work and childcare and enjoy fewer opportunities to ‘job out’ within a discriminating labour market. Let us take a closer look at these dynamics.

Access to education is the key determinant of employment opportunities in Belize (Naslund-Hadley, Navarro-Palau, and Prada Citation2020). The Inter-American Development Bank estimates that Belizeans with primary schooling (K-8 equivalent) fare no better on the job market than those without because ‘the quality of primary education is so low’ (Naslund-Hadley, Navarro-Palau, and Prada Citation2020, 16). Workers may double their monthly salary with a high school diploma (from $210 to $448), whereas vocational schooling offers a 3-fold salary increase ($652) and University degree promises a 5-fold increase ($1107). Although the drive to educate is universal, access to quality education is not. Less than half of Belizean children receive a secondary education. The education system therefore mediates class mobility and reinforces a hierarchy of labour power. Given the discrimination in the educational system and the labour market, those at the bottom are predominantly poor, rural, women, and/or indigenous. The most recent Belize Labour Force Survey Report notes that Toledo represents almost 50% of those outside of the labour force and the highest percentage of subsistence farmers (43.6%) most of them Maya (SIB Citation2021b).

Belize’s education system is built on colonial premises with the cultural and ideological functions of the British empire and Jesuit missionaries (Lewis Citation2000; McGill Citation2012). Today churches and the Government, supported by foreign assistance, manage a weak and disheveled educational infrastructure (Shoman Citation1995, Citation2011).Footnote16 Census data offers insight into uneven access to secondary education in Belize and Toledo district (). In 1991, a total of 130 people in all Maya villages (1.2% of the population in those communities) were enrolled in high school (99) or had obtained a diploma (31). At that time, a degree required students to live full-time in the coastal city of Punta Gorda, where the Catholic high school opened in 1983. This meant that access to secondary education has long been constrained to a small, privileged minority of Maya households in the villages and small towns near the coast (see, for example, San Pedro Colombia and San Antonio in ), who could afford tuition and fees of $775 per year (McClusky Citation2001). Between them, the three remote villages of our study area had one resident with a high school diploma in 1991. This increased to 11 by 2000. In 2001, the Government of Belize established Julian Cho Technical High School (JCTHS).Footnote17 JCTHS is now the second largest high school in Belize, and six additional secondary schools are today located in Toledo including a Mennonite high school, two more technical schools, and the Maya-led Tumul K’in Center of Learning. By 2010 the number of Mayan people enrolled in high school or having graduated jumped three-fold. Some remote villages like Santa Cruz and Aguacate saw ten-fold increases. In October 2020, the Jesuit mission announced that two high schools are planned for remote communities of Toledo district.

Table 1. Census data on high school education in select Maya villages, all Maya villages (aggregated), Toledo district, and Belize. A ‘Maya village’ is defined as having 30 or more residents, at least 2/3rds of whom speak Mopan and/or Q’eqchi’. San Antonio and San Pedro Colombia are the two largest Maya towns. The data show increasing enrolment and number of diploma-holders living in the Maya communities, but that rural Toledo still lags far behind the national average.

The main impediment to secondary education today is the cost of school. Although costs differ across institutions and circumstances, a reasonable estimate of four years at JCTHS is US$1750.Footnote18 So while Maya households aspire to send all their children to high school, this is rarely possible. In 2010, 19 out of 52 eligible children (ages 13–17) from Aguacate attended, 32 out of 86 attended in Jalacte, and 26 out of 41 in Santa Cruz (SIB Citation2010). About 1 in 4 students at JCTHS drop out after their first or second year, likely because the tuition subsidy ends after year two (Ministry of Education Citation2019). Households must balance school expenses not only with consumer goods purchases but also with primary school expenses that are compulsory for all Belizean children ($75–150 per child per year).

Boys have consistently outnumbered girls for high school enrolment and diplomas, a pattern which has grown most acute in the Maya villages (). By contrast, at a national average the opposite is true: Belizean women hold more diplomas than men. The 2011 valedictorian of JCTHS offers this explanation: ‘My dad … did not want to send me and my older sister to school because he says that only boys are supposed to go. Girls all they do is go to school [and] get pregnant’ (Oxa Productions Citation2012). Parents may harbour sentiments that girls ‘turn out bad’ (Gregory Citation1987), while others have not wanted girls to travel and live alone in town (McClusky Citation2001).

In Toledo only the most well-to-do households can afford University of Belize’s tuition of $1,500 per year, not including food, housing, books, computer, and other expenses (UB Citation2020). The gendered division of labour partly explains why, at a national level, women earn more high school and college diplomas than men: it is the pathway for employment outside the village; class mobility practically requires a high school diploma (Bulmer-Thomas and Bulmer-Thomas Citation2012). And yet, in the Toledo District, the gap between men and women graduating high school is growing, despite improving gender balance in Toledo’s high school enrolment (). Our interpretation of these data is that while young Maya women enroll in high school in substantial numbers – taking advantage of the first two subsidized years, for instance – relatively few rural Maya families can afford to support their children through four years of secondary school. Gender bias reduces girls’ educational attainment.

Table 2. Evolving gender gap in rural Toledo education compared to the district and national average. While total enrolment has moved towards greater gender equity, graduation rates have not.

This gender gap in education has important outcomes for employment patterns.Footnote19 In 2010, the unemployment rate for women in Toledo was 39%: significantly higher than for Belizean women generally (33%) or for men in Toledo (13%) (SIB 2011; cited in Bulmer-Thomas and Bulmer-Thomas Citation2012, 152). Even with a diploma, many sectors of the economy systematically discriminate against Maya women: police, military, security, construction, agricultural work, and the like are male occupations.Footnote20 Their best prospects lie in the service sector, where ∼90% of employed Belizean women sell their labour – principally in schools, hotels, shops, hospitals, and offices. A high school education, if not further education, is typically expected for these positions. For Maya women, then, the main economic strategy is to pursue education and join the salaried proletariat in the tertiary sector.Footnote21 Although we have only anecdotal evidence to support the claim, we suspect that the wage premium from education is much greater for Maya women: by obtaining a high school or college degree, a women’s wage ratio rises faster than for men. Whereas Maya men may circulate between job and milpa even without schooling, the labour market is tilted heavily against Maya women who lack formal education.

In sum, schooling today presents the central pathway for Maya peasants to join the ranks of the proletariat. Households face a dilemma between the desire to educate children and the financial burden of doing so. Given the historical conditions of rural poverty and discrimination in the labour market, this contradiction reinforces the subaltern location of Maya people within the division of labour. It also contributes to driving households along a second pathway for upward mobility: land use change from customary milpa to commercial farming.

4. Land use, agroecological change, and class conflict

We have seen that capitalism is re-shaping household reproduction and incorporating Maya people into the gendered dynamics of education and wage labour. We now consider how commercial land use reinforces class processes and generates new conflicts. While land use and agroecological changes are everywhere apparent in Toledo District (especially when looking at the satellite record: e.g. Esselman et al. Citation2018), they are uneven. To interpret differential pathways, we consider agrarian change since 1981 in three neighbouring villages.

4.1. Aguacate

In the early 1980s, Aguacate households farmed milpa for both subsistence and petty commerce (Wilk Citation1981, [Citation1991] Citation1997). Multiple intersecting factors have since altered the course of land use in the village. In the late 1980s, the UN’s Toledo Small Farmers Development Project (TSFDP), preceded by the Toledo Rural Development Project (TRDP), recruited 1,600 Maya households across the district into an agricultural modernization program (IFAD Citation1994; Wainwright Citation2008). The projects specifically targeted Aguacate’s lowland soils in the eastern half of the village, which are suitable for cattle ranching and mechanized farming. Male heads of household obtained loans and private leases on 30–50 acre parcels of communal land, but the project ultimately failed to achieve its stated objectives as technical assistance and marketing opportunities fell through. Rather than have the banks seize their lands, in 2002–2006 community members successfully lobbied the Belizean government for debt cancellation.

The project indelibly altered the social relations of land ownership and management. As opposed to returning parcels to a communal basis, the village decided, through democratic consensus, to maintain them on a de facto private basis.Footnote22 Irrespective of legal standing, privatization implies that land has become a commodity: ownership has exited the commons and is conferred from one household to the next. This incident demonstrates how community members reconceived their interest, at least in part, in terms of private individual property. Lowland parcels soon began to trade hands, along with their invalidated lease documents. A few wealthier households, namely those with steady income outside of the village, accumulated multiple parcels; three families now control approximately two-thirds of them. Hence, a sizable portion of Aguacate’s communal land is divided along class lines.

The consolidation of private property coincided with an improved roadway that cuts through the lowlands, facilitating intensified land use, electricity, daily commutes to town, and access to high school. At least one additional element has been requisite for successful commercial farming: collaboration with Mennonites who settled in neighbouring Blue Creek village in the 1980s promising agricultural assistance in exchange for land.Footnote23 They soon established a congregation within Aguacate and recruited members on the condition of church rules. Maya households that join the Mennonites enjoy material benefits of an emergent rural bourgeoisie of southern Belize, including tractors, trucks, cattle, credit, wage work, a machine shop – infrastructure that is largely unavailable to members of the other six village churches.

For most residents, milpa farming provides a tenuous survival that is continually undermined by social and ecological change. Milpa has shifted in ways described earlier in this paper, including greater use of herbicides and hired labour. Grass weeds (e.g. Rottboellia cochinchinensis) inundate fertile soils on the lowland riverbanks, spread by pastures, mechanized farming, forest degradation, and floods (Peller Citation2021). Climate and hydrological changes are also presenting challenges as flood events become more frequent and unpredictable, including an unprecedented dry-season event in February 2018 that destroyed lowland milpas. Meanwhile the pumpkin seed boom has felled remote forests in the village highlands, enflaming both anxieties over environmental degradation in the community, and tensions over boundary demarcation and land use competition with neighbouring villages.

Another source of tension flows from development and foreign aid financing. Eco-tourism began modestly in the 1990s, but over the past decade it eclipsed agriculture as the central object of development in Aguacate. At the time of research, most households participated in guest house, craft, and jungle tour guiding schemes, coordinated through an NGO headed by village political leaders. Yet few tourists venture to Aguacate and the sector evaporated during the pandemic. Beginning in 2019, eco-tourism leaders saw opportunity in the Indigenous and Community Conserved Areas (ICCA) and REDD+, with the aim to enroll over 1000 acres in these programs and hire villagers as conservationists and tour guides. Benefits from these projects have been shared widely in the village (albeit unevenly); most village members have supported them. But dissent was organized by a minority of households living on the western margin of the village, whose grievances include unequal benefit distribution and restrictions on land use. These antagonisms boiled over in November 2018 when dissenters protested a grant inauguration ceremony and destabilized village institutions.

The cyclical and overlapping dynamics of land use in Aguacate complicates another important dynamic: residents broadly support the Maya’s struggle for communal land rights. Most village lands remain un-privatized and it is unlikely that any new titles will be granted soon. Yet on the ground there is class process – the complex pathways of household reproduction, social differentiation, and conflict that play out on the land and drive unequal land distribution.

4.2. Jalacte

Travelling westward through the Toledo uplands on a freshly paved international highway, broadleaf tropical forest begins to fragment by the roadside. Around a bend into Jalacte village, the horizon opens into an indefinite grass savannah. Jalacte began modestly in 1972, as a small Q’eqchi’ settlement in the dense forests where nearby Mopan villagers sometimes hunted (TMCC Citation1997). In 1983–1984, village population began to swell as the Guatemalan military pursued a genocidal campaign onto Maya civilians and rebels in the Verapaz. Survivors sought refuge in the Guatemalan Petén and southern Belize; some ended up in Jalacte, built homes and converted the fertile upland soils into milpa farms (Wainwright et al. Citation2015).

Around the turn of the millennium another rapid shift in land use began. About a decade after Q’eqchi’ migrants settled in Jalacte, Ladino households had begun to establish a neighbouring village in Guatemala called Santa Cruz Frontera. Jalacte village soon became dependent on ‘Frontera’ for consumer goods, crop sales, and transportation. In time, economic ties deepened as ranchers formed inter-marriages and land-sharing arrangements with opportunistic Q’eqchi’ households. In a relationship called mediante, established ranchers supply calves in exchange for half the adult animals’ value until the new ranch operates independently. Today, about ten households manage cattle ranches and control half the agricultural soils of Jalacte village. They purchased much of this land from poor households, informally if not illicitly (i.e. without involving the state functions of land survey, taxation, and property transfer, nor the Maya Leaders Alliance). The price paid – $200–300 per hectare – is no small sum in Toledo. Ranchers frequently hire farm workers, grow large commercial milpas, operate trucks and buses across border, and adopt a machista cowboy affect.

The remaining 140 households of Jalacte are cash poor, Q’eqchi’-speaking families whose livelihoods center on intensive milpa farming. They cultivate larger areas per year than households in other Maya villages because they must sell surplus maize and beans at exploitative prices in Frontera. Households work collectively to plant milpa, but also hire landless workers from Guatemala during labour bottlenecks. The agroecological problems of milpa farming are most extreme in Jalacte. Over the past three decades, Jalacte village has lost more than 75% of its forest cover. Small farmers labour in an undulating sea of grass savanna, dissected by pathways lined with barbed wire and pasture. No tract of arable soil is left unclaimed, sometimes only a shrub indicating one household’s plot from another.

As fallow lengths plummeted to a year or less, unforgiving weed ecologies have taken root. Farmers sometimes use Mucuna pruriens (‘mucuna bean’) cover crop to help control these species, but more often they spray herbicides multiple times per season. Soil analyses indicate that severe soil degradation and erosion are linked to the increased frequency of burn events, since farmers routinely set fire to their fields before planting crops despite diminishing fallow (Peller Citation2021). A vicious spiral of soil degradation brings greater grass weed infestation, more herbicide use, and more nitrogen and phosphorous fertilizer application.

The class dynamics of Jalacte have produced sharp divisions and conflicts that undermine customary village institutions, namely alcaldehood (or village self-government) and communal land management. While Q’eqchi’ village leaders are keenly aware of problems such as land grabbing, cattle ranching, and environmental degradation, they lack sufficient power to challenge them. Communal land use is further complicated as land becomes more rigidly divided among households and inherited from father to son. As one village explained, ‘Whenever I came here [in 1984] I found the high bush. So, it’s my land now.’

In 2015–2016, two events occurred that exacerbated the existing dynamics. First, the new international highway became trafficable, which runs through Jalacte and plugs Toledo district with the Mesoamerican highway system. Second, after the completion of the highway, the Government constructed a border checkpoint without the consent of Jalacte villagers (damages for which, following a court case, the government now owes them compensation). The checkpoint blocks off Jalacte’s entrance eastward into Belize, and residents complain of harassment by security personnel including a ban on transporting crops and livestock into Belize. These events have increased land pressures and further marginalized the ability of households to uphold customary norms: Jalacte’s location in the crosshairs of international conflict has superseded any means of local control.

With little land or livelihood opportunities, parents squeeze the soil to send their children to school and out of the village. Others save money and head north for the US by way of Guatemala. For the rest of Toledo district, Jalacte has become something of a harbinger: it is possible (though not inevitable) that its experiences indicate a bleak future, where cattle pasture supplants the forests and class processes dissolve the cohesion of communal land management.

4.3. Santa Cruz

Santa Cruz is a mixed Mopan and Q’eqchi’-speaking village in the productive upland soils east of Jalacte, along the highway route. Santa Cruz village leaders are among the vanguard of activists who have challenged the government of Belize in court. Consequently, the struggle for collective land rights enjoys majority support in the village. Class differences are less pronounced than in Aguacate or Jalacte. Most households farm milpa on communal land and work occasional jobs outside the village. Neither Mennonites nor Guatemalan ranchers (the emergent rural bourgeoisie) enjoy significant presence here, although this is beginning to change.

Land management has remained stable in recent decades as farmers continue to rotate their milpas on 5–15 year fallowing cycles. However, milpa is subject to similar problems as elsewhere, including grass weeds and herbicide use, crop failures during El Niño-related drought events in 2016 and 2019, and expansion of pumpkin monocultures in the remote forests. The new highway has facilitated many additional changes: intensified farming along roadsides, hourly bus runs, better access to high school, and closer economic ties with the cross-border traffic. The highway was completed in 2015; by 2019, the number of cattle pastures in the village increased from one to four, including a large and contentious pasture on the new highway established through mediante. Cattle pastures have inspired enormous tensions within the community, with majority opposition but a persistent minority. One village elder articulated the majority view in Santa Cruz plainly:

It is not good to have a pasture … You will lose all of the trees, all of the topsoil going to the river. You can’t farm there anymore … 20 years ago in Jalacte, you could hear the baboons in the big trees … but right now you can’t hear that again, all gone … our grandfathers taught us how to manage the land, because we want to make a good corn.

While cattle ranching meets resistance, greater numbers of Santa Cruz households have invested in cacao. Although vastly different agroecologically, both forms of commercial land use carry the same effect on property relations. As one young Santa Cruz farmer explained, ‘If I plant cacao [the land] is mine. Same thing for pasture because I will put wire on it.’ Gesturing towards his partner and newborn, he continued, ‘I don’t know what life is coming ahead. I need to do some business … when you sell that [cattle] money come fast, [and I] need money for the baby.’ A few months after our interview, the couple shuttered their thatch home, sold their small livestock, and left the village to find work on the coast – only to return two years later, no less poor and conspiring to plant pasture.

In Santa Cruz, the list of changes on the land continues. Frequently they find expression through village politics. Land use conflicts feature regularly in village meetings, whether they concern a neighbouring village, an objectionable land claim within the village commons, or political issues surrounding land rights, electoral campaigns, forest conservation, development projects, and more. The resulting conflicts in turn complicate the struggle for communal land rights. Over the past decade, the minority opposition to communal land rights has become more coherent and better organized. This is partly the result of politicians and agents provocateurs (local operatives aligned with national political parties) who conspire with the Belizean government to sow dissent and agitate households in favour land privatization. But opposition is also internal to the community, rooted in class processes that drive households towards claiming private land for commercial farming.

5. Conclusion

The Maya villages of Toledo persist in a space that is marginal to global capitalism. This has allowed a degree of autonomy and maintenance of some non-capitalist (reciprocity based) social relations that revolve around a communal land tenure system. The existing communal land tenure system is rooted in milpa farming, where land is perceived as source of sustenance, its product consumed by the household/producer. Demand for land is limited by the labour capacity of the household and its focus on subsistence. Additional labour power is generated through reciprocal labour exchange where the focus is to extract sustenance, not the production of commodities for market exchange. Customary practices regulate this system. These constitute key non-capitalist elements: land and labour are required for the expansion and accumulation of capital, but they cannot be created by capital.

Greater integration of these villages with markets is changing land use patterns and labour relations. The separation of labour from land and the commodification of each – the condition for what Marx (1867) analysed as the ‘so-called original accumulation’ of capital – has accelerated since the end of formal colonialism in 1981. Both become commodities to be exchanged in the market economy and mixed with capital to produce more commodities. Changes in land use and labour relations produce class differentiation, and class differentiation produces changes in land use. As land becomes capital there is an increasing demand to divide the customarily managed forests, introducing conflicts that threaten the economy of labour reciprocity and the customary land tenure system: pre-capitalist social relations that serve as proposed basis for building an alternative future.

To a significant degree, these dynamics explain the emergence of the Maya movement, which has been predicated upon and directed towards the maintenance of autonomous social relations rooted in collective land ownership. These relations however have been shifting under the hegemony of capital. Economies of reciprocity are weakened by increasing demands for cash as households sell labour power, agricultural commodities, and in some instances land. These processes deepen differentiation along lines of class and gender. This differentiation is driven through educational attainment and new forms of land use. New land use patterns disrupt customary communal relations that are based on non-capitalist ways of relating to the land and each other.Footnote24

Maya actors are not oblivious to the threats that the non-capitalist elements of Maya society face. In 2019, three Maya organizations articulated a vision of the future in a document that includes the following statement:

While unity and community are a strength, we also recognize that it is under constant threat. … [T]he external divisive forces and the rapid change in our communities amplify and create new divisions and present a challenge to coming together and joining our words and our thoughts. … [W]e are not naïve to the fact that this land, unity, and culture is under pressure. … Some of these pressures are external dividing forces such as religion, politics, and foreign interests. However, we also recognize that there are internal factors such as poor leadership, local people who want to sell land, and sectors of Mayan society who do not agree with a communal land vision. (JCS, MLA, and TAA Citation2019, 30)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the communities where we conducted fieldwork for this paper; the Julian Cho Society, Toledo Alcaldes Association, Maya Leaders Alliance; and Galen University. We would also like to thank our anonymous reviewers for their helpful criticism of our paper. We thank funders for their support. All errors remain our responsibility. We thank Shiguo Jiang for creating the map (Figure 1). We thank Will Jones, Kristin Mercer, and Lauren Salisbury for their assistance and criticisms.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Henry Peller

Henry Peller is a farmer and independent researcher in rural southeastern Ohio. He completed a Ph.D in soil science at The Ohio State University, where he studied soil fertility and political economy of agriculture in southern Belize.

Filiberto Penados

Filiberto Penados Ph.D, is Research Director and Associate Professor of Indigenous and Development Studies at Galen University. His scholarship focuses on indigenous education and development.

Joel Wainwright

Joel Wainwright is Professor of Geography at Ohio State University, where he studies political economy, environmental change, and social theory.

Notes

1 For a review of the literature on agrarian Marxism, see Levien, Watts, and Hairong (Citation2018) and the special issue it introduces.

2 By ‘milpa’ we refer to the fields cultivated by Maya maize farmers. For present purposes, the definition of ‘peasant’ from Article 1 of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Peasants (Citation2018) will suffice: ‘any person who engages or who seeks to engage alone, or in association with others or as a community, in small-scale agricultural production for subsistence and/or for the market, and who relies significantly, though not necessarily exclusively, on family or household labour and other non-monetized ways of organizing labour, and who has a special dependency on and attachment to the land’.

3 In 2015, stunted growth was found in 40% of Maya children in Toledo, a number that exceeds any other ethnicity or district (SIB and UNICEF Citation2017). Among the employed population, underemployment (those employed but with insufficient hours) is highest in Toledo at 36.7%, about twice the national average (SIB Citation2021b).

4 See TMCC and TAA (Citation1997) and Wainwright (Citation2008, chapter 5).

5 Customarily, the milpa is a swidden, where crop production rotated with secondary forest regrowth. Fallow length varies. See Wilk ([Citation1991]Citation1997), Peller (Citation2021).

6 A non-exhaustive list of studies on land use and livelihoods in rural Toledo district includes Sapper (Citation1899)Citation2000, Wright et al. (Citation1959), Wilk (Citation1981), Osborn (Citation1982), TMCC and TAA (Citation1997), Wilk ([Citation1991]Citation1997), Emch (Citation2005), Zarger (Citation2009), Grandia (Citation2012), Wainwright et al. (Citation2015), Stanley (Citation2015) and JCS, MLA, and TAA (Citation2019). Remarkably, none of these studies examines class processes in the Maya communities (Wilk [Citation1991]Citation1997 is an exception that proves the rule).

7 E.g., Tania Li’s Land’s End (Citation2014) shows how the spread of cacao production in rural Sulawesi, Indonesia, produced new forms of class stratification in indigenous communities which promptly internalized the new ideas and practices of capitalist society. (Cacao has also been a driver of land parcellation and privatization in southern Belize, but we do not emphasize it here because of the diverse land use strategies pursued by Maya farmers.)

8 Each of this paper’s authors has each worked in southern Belize for years (Peller since 2015, Penados since 2000, and Wainwright since Citation1995).

9 A vibrant literature has examined the economic history and ethnohistory of southern Belize: Wright et al. (Citation1959), Wilk (Citation1981), TMCC and TAA (Citation1997), Wilk ([Citation1991]Citation1997), Wainwright (Citation2021a, Citation2021b).

10 See Shoman and Wainwright (CitationForthcoming, Chapter 1).

11 Elsewhere we have referred to this line of argument by the name ‘the Jones-Wilk hypothesis’ (Wainwright Citation2021b), for Grant Jones and Richard Wilk who developed the hypothesis in parallel in the 1980s and elaborated it in their affidavits for the legal cases against the Government of Belize See also Wainwright (Citation2015).

12 While the Spanish introduced the term ‘alcalde’ (meaning magistrate or mayor), in the Maya communities of Belize it references a form of governance rooted in customary practices. Each community elects an alcalde to serve a two-year period. Alcaldes serve as lower magistrate enforcing statutory law. Their customary functions include promoting community harmony, implementing customary law, overseeing the customary land tenure system, facilitating community decision-making, and representing the collective voice of the community. The Toledo Alcalde Association (TAA) was formed in 1991 and subsequently legally incorporated with assistance from the Toledo Maya Cultural Council. Today, TAA is comprised of the Alcaldes from all the 39 communities and serves as a platform for dialogue and concerted political action.

13 All dollar amounts in this paper have been converted to US dollars. The Belizean dollar is tied to the US dollar at a conversion rate of 2:1.

14 Narcotics flow through Toledo district into North American markets. Presently, this clandestine activity does not feature centrally in the three villages we examine, so is not considered a major factor in our study. Elsewhere in Central America, the link between narcotics and land use is more immediate (see Devine et al. Citation2018).

15 In 2019, Santa Cruz had four pastures totaling about 50 acres, Aguacate had nine pastures totaling approximately 300 acres, and Jalacte – one of the most dramatic cases in southern Belize – had about half the village farmland, upwards of 1000 acres, under pastures belonging to 10 households.

16 ‘Belize’s education system is still based on the British model created by [an elite] that didn’t want to educate the colonized, especially ethnic minorities, and that limited access to secondary education. The schools were run by churches, whose focus was on literacy and religious teaching for the masses, with secondary education introduced later for the middle and upper classes’ (Shoman Citation2011, 373).

17 The school is named for Julian Cho, Maya leader who mobilized Maya communities for collective lands until dying under suspicious circumstances on 1 December 1998.

18 Based on book rentals ($50–100 per year), school lunch ($1.25–3.00 per meal), uniform ($50), tuition after the first two years of government subsidy ($250), cell phone and computer fees ($250), and subsidized bussing. In fact, costs are often much higher, once including internet, printer, and computer usage regularly needed for homework assignments, and a high school graduation party.

19 This is only one factor contributing to sharpening economic inequality between genders in rural Toledo. As land has passed from community to private control in some Maya communities, Maya men have been systematically favoured in the granting of titles. Hence the tendency to privatize indigenous land in rural Toledo works against women.

20 For example, the 2019 intake of Belize Defense Force personnel included 90 men and 8 women.

21 Unfortunately for Maya women from rural Toledo, the District has the smallest tertiary sector of all the Districts. Upward mobility therefore implies leaving the village.

22 De facto privatization differs from de jure privatization (sanctified by a government-issued title), which is uncommon in the remote villages of Toledo. Private leasehold lands are common in larger rural towns due to political graft and foreign real estate development. Aguacate land holders retain the original, paper-copy lease title issued by the government (a remarkable feat in the humidity of Toledo) as proof of their claim. But legally these leases were cancelled in 2006.

23 Mennonites initially moved from Mexico and Canada to northern Belize in the mid-20th C upon negotiation with the Government to increase domestic food supply in return for land and autonomy (Everitt [Citation1983]Citation2009; Shoman Citation2011). Today, distinct groups of Belizean Mennonites persist including the most capitalized, enterprising farmers in the country as well as those who abstain from modern technology altogether, each with varied ethic and settlement histories (Roessingh Citation2007). Some maintain close relations to family in the southern US, and hence enjoy prodigious access to agricultural machinery.

24 Similar conclusions have been drawn in other parts of Latin America, but in Belize there is a paucity of class analysis. Why? Three answers suggest themselves. First, Belize is unusual for its lack of Left or socialist parties and a paucity of Marxist scholarship. Apart from Assad Shoman, practically no Belizean intellectuals have produced critical political economy since independence. Second, the field of Maya research in Belize has been dominated by anthropologists (including archaeology) from the USA, UK, and Canada. This discipline has largely lost the interest in class and Marxism that marked Anthropology in the 1970s. Third, prior to the 1990s, most organizing in the Maya communities of Toledo emphasized shared poverty, insecure land tenure, and low prices received for farm goods – standard peasant demands from a class basis. This changed during the 1990s to a greater emphasis on indigenous rights. While temporal correlation does not necessarily imply causation, there are strong grounds to argue that the decline of class consciousness is the result of the shift in political emphasis toward legal strategies to win justice through multiple legal cases to defend land rights. For, while the cases have been successful, justice has not been achieved, and the class politics of the movement have become more liberal.

References

- Bernstein, H. 2010. Class Dynamics of Agrarian Change. Sterling, VA: Kumarian Press.

- Bulmer-Thomas, B., and V. Bulmer-Thomas. 2012. The Economic History of Belize: From the 17th Century to Post Independence. Benque Viejo: Cubola Books.

- CCJ (Caribbean Court of Justice). 2015. “Consent Order Between the Government of Belize and the Maya Communities of Toledo.” Unpublished manuscript (court decision), April 22.

- Chayanov, A. 1986. The Theory of Peasant Economy. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Cleary, P., K. Mercer, R. Wilk, J. Wainwright, and K. Usher. 2021. “Changes in Food Consumption in an Indigenous Community in Southern Belize, 1979-2019.” Food, Culture & Society. doi:10.1080/15528014.2021.1884403.

- Conteh, A. 2007. Judgment in the Supreme Court of Belize: Consolidated claims no. 171 and 172 of 2007, A. Cal, et al v. Belize.

- Devine, J., D. Wrathall, N. Currit, B. Tellman, and Y. Reygada. 2018. “Narco-Cattle Ranching in Political Forests.” Antipode 52 (4): 1018–1038. doi:10.1111/anti.12469.

- Emch, M. 2005. “The Human Ecology of Maya Cacao Farming in Belize.” Human Ecology 31 (1): 111–131. doi:10.1023/A:1022886208328.

- Esselman, P., S. Jiang, H. Peller, D. Buck, and J. Wainwright. 2018. Landscape Drivers and Social Dynamics Shaping Microbial Contamination Risk in Three Maya Communities in Southern Belize, Central America. Water 10 (11): 1678.

- Everitt, J. [1983] 2009. “Mennonites in Belize.” Journal of Cultural Geography 3 (2): 82–93. doi:10.1080/08873638309478597.

- Gahman, L., F. Penados, and A. Greenidge. 2020. “Indigenous Resurgence, Decolonial Praxis, Alternative Futures: The Maya Leaders Alliance of Southern Belize.” Social Movement Studies 19 (2): 241–248. doi:10.1080/14742837.2019.1709433.

- Gramsci, A. [1926] 2000. The Gramsci Reader: Selected Writings, 1916-1935, Edited by D. Forgacs. New York: New York University Press.

- Grandia, L. 2012. Enclosed: Conservation, Cattle, and Commerce among the Q’eqchi’ Maya Lowlanders. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Gregory, J. 1987. “Men, Women and Modernization in a Mayan Community.” Belizean Studies 15: 1–32.

- IFAD. 1994. “Belize: Toledo Small Farmers Development.” https://www.ifad.org/en/web/ioe/evaluation/asset/39830226

- JCS (Julian Cho Society), MLA (Maya Leaders Alliance), and TAA (Toledo Alcaldes Association). 2019. The Future We Dream. Punta Gorda: Unpublished Manuscript.

- Lenin, V. [1899] 1964. The Development of Capitalism in Russia. Lenin's Collected Works. 4th ed., Volume 3. Moscow: Progress Publishers.

- Levien, M., M. Watts, and Y. Hairong. 2018. “Agrarian Marxism.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 45 (5-6): 853–883.

- Lewis, K. 2000. “Colonial Education: A History of Education in Belize.” Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association. Accessed 18 October 2021. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED448087.pdf.

- Li, T. 2014. Land’s End: Capitalist Relations on an Indigenous Frontier. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Mao, T. [1927] 1965. Report on an Investigation of the Peasant Movement in Hunan. Selected Works Vol. 1. Peking: Foreign Language Press.

- Marx, K. 1852. 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. New York: International Publishers.

- Marx, K. [1967] 1990. Capital Vol. 1. London: Penguin.

- McClusky, L. 2001. Here, Our Culture is Hard: Stories of Domestic Violence from a Mayan Community in Belize. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

- McGill, A. 2012. “Aal a wi da wan?: Cultural Education, Heritage, and Citizenship in the Belizean State.” Dissertation, University of Indiana.

- Mesh, T. 2017. “Alcaldes of Toledo, Belize: Their Genealogy, Contestation, and Aspirations.” Diss., University of Florida.

- Ministry of Education (Belize). 2019. Abstraction of Education Statistics 2018/19. Belize City.

- Naslund-Hadley, E., P. Navarro-Palau, and M. Prada. 2020. Skills to Shape the Future: Employability in Belize. Belize City: Inter-American Development Bank.

- NHDAC (National Human Development Advisory Committee). 2010. 2009 Belize Country Poverty Assessment Vol. 1 Main Report. Belmopan.

- Osborn, A. 1982. “Socio-Anthropological Aspects of Development in Southern Belize.” Unpublished manuscript. Punta Gorda: TRDP.

- Oxa Productions. 2012. “Julian Cho Technical High School”. Accessed 18 October 2021. https://vimeo.com/33385458.

- Peller, H. 2021. “Soil Fertility, Agroecology, and Social Change in Southern Belize.” Diss., The Ohio State University.

- Roessingh, C. 2007. “Mennonite Communities in Belize.” International Journal of Business and Globalization 1 (1): 107–124.

- Sapper, K. [1899] 2000. “Early Scholars’ Visits to Central America.” Occasional Papers 18. Costen Institute of Archaeology UCLA.

- Shoman, A. 1995. “Belize: An Authoritarian Democratic State.” In Backtalking Belize: Selected Writings, edited by A. Macpherson, 189–218. Belmopan: Angelus Press.

- Shoman, A. 2011. A History of Belize in 13 Chapters. Belize City: Angelus Press.

- Shoman, A., and J. Wainwright. Forthcoming. Belize: A Critical History. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- SIB (Statistical Institute of Belize). 2010. “Census Population by District, 1921-2010.” http://sib.org.bz/statistics/population/

- SIB (Statistical Institute of Belize). 2021a. “2018/2019 Poverty Study.” Belmopan, Belize.

- SIB (Statistical Institute of Belize). 2021b. “Belize Labor Force Survey Report.” Belmopan, Belize.

- SIB (Statistical Institute of Belize) and UNICEF Belize. 2017. Belize Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey, 2015–2016, Final Report. Belmopan.

- Stanley, E. 2015. “The Protestant Ethic and Development Ethos: Cacao and Changing Cultural Values among the Mopan Maya of Belize.” Diss., University of Virginia.

- Steinberg, M. 2002. “The Globalization of a Ceremonial Tree: The Case of Cacao (Theobroma Cacao) among the Mopan Maya.” Economic Botany 56 (1): 58–65.

- TMCC (Toledo Maya Cultural Council) and TAA (Toledo Alcaldes Association). 1997. Maya Atlas: The Struggle to Preserve Maya Land in Southern Belize. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic.

- UB (University of Belize). 2020. “University of Belize Tuition and Fees.” https://www.ub.edu.bz/admissions/tuition-and-fees/.

- UN. 2018. “United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas.” Accessed 18 October 2021. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/1650694?ln = en#record-files-collapse-header.

- Wainwright, J. 2008. Decolonizing Development: Colonial Power and the Maya. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Wainwright, J. 2015. “The Colonial Origins of the State in Southern Belize.” Historical Geography 43: 122–138.

- Wainwright, J. 2021a. “The Maya and the Belizean State: 1997-2004.” Latin American and Caribbean Ethnic Studies, 3: 1–30.

- Wainwright, J. 2021b. “How Does the Law Obtain Its Space? Justice and Racial Difference in Colonial Law: British Honduras, 1821.” International Journal of the Semiotics of Law 34: 1295–1330.

- Wainwright, J., S. Jiang, K. Mercer, and D. Liu. 2015. “The Political Ecology of a Highway Through Belize's Forested Borderlands.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 47 (4): 833–849.

- Wainwright, J., and C. Zempel. 2018. “The Colonial Roots of Forest Extraction: Rosewood Exploitation in Southern Belize.” Development and Change 49 (1): 37–62.

- Wilk, R. 1981. “Agriculture, Ecology and Domestic Organization among the Kekchi Maya.” Diss.. University of Arizona.

- Wilk, R. [1991] 1997. Household Ecology: Economic Change and Domestic Life among the Kekchi Maya in Belize. DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press.

- Wilk, R. 2006. Home Cooking in the Global Village: Caribbean Food from Buccaneers to Ecotourists. New York: Berg.

- Wright, A. C. S., D. H. Romney, R. H. Arbuckle, and D. Vial. 1959. Land in British Honduras: Report of the Land Use Survey Team. London: HMSO.

- Zarger, R. 2009. “Mosaics of Maya Livelihoods: Readjusting to Global and Local Food Crises.” Annals of Practice 32: 130–151.