ABSTRACT

This article explores the complexities of agency in contemporary territory-based mobilisations in the countryside by focusing on water struggles in Turkey. Using a historical-spatial approach, it combines agrarian political economy analysis with human-nature interactions. Through an analysis of cash crop production and urban-rural interactions, this contribution argues that capitalist agrarian transformation in Turkey led to the emergence of an ‘urban middle class with peasant characteristics’, with a strong capacity for mobilisation and alliance-building. It also argues that this group enabled abstraction, place-framing and aestheticised resistance, common elements we observe in contemporary territorial mobilisations.

1. Introduction

This article delves into the century-old problematique of peasant studies: ‘Who acts in rural struggles?’ in light of the recent theoretical advancements in the areas of political ecology, critical political economy and critical geography. Peasant mobilisations – whether as revolutions, rebellions or protests – have always been on the agenda of social scientists, though to different degrees. Peasant revolutions in Russia and China (Bianco Citation1975; Skocpol Citation1994) and questions over peasants in emerging nation-states have captured the attention of social scientists, engendering a large corpus of literature and theorisation on the different segments and classes of the peasantry (Kurtz Citation2000). Over the last few decades, the acceleration of primitive accumulation through modern enclosures, land grabs (Borras et al. Citation2012; McMichael Citation2012), water grabs (Franco, Mehta, and Veldwisch Citation2013; Khagram Citation2018; Rulli, Saviori, and D’Odorico Citation2013), ‘green and blue grabs’ (Corson and MacDonald Citation2012; Fairhead, Leach, and Scoones Citation2012; Hill Citation2017; Rocheleau Citation2015), as well as the proliferation of extractive industries, has given studies of peasants and capitalists a new spatial dimension extending beyond the direct productive relationship between the soil and the peasant. This is most evident in, for example, investments in hydropower, minerals, roads, dams and water management, which alter rural areas and livelihoods.

The spatialisation of the transformation in the countryside is also underpinned by the decline in the relative significance of agricultural production in rural livelihoods, and the rise of the ‘new peasantry’ (Van der Ploeg Citation2018), off-farm incomes (Reardon, Berdegué, and Escobar Citation2001), and deepening rural-urban linkages and hybridities. Bebbington (Citation2007) emphasises the need to talk about the ‘rural question’ rather than the agrarian question since resource rushes have triggered a wave of commodification and enclosures. Recent theoretical advancements in the ‘spatial turn’ have brought a reframing of capitalist expansion as the dialectics of enclosures versus commoning practices (De Angelis Citation2007; Linebaugh Citation2014; Sevilla-Buitrago Citation2015). Geographers have also contributed to this debate by unveiling the central role of enclosures in restructuring socio-spatial formations (Sevilla-Buitrago Citation2015).

We have also witnessed a rise in movements, mobilisations and protests accompanying these new forms of enclosures and the further penetration of extractive industries into rural areas (Bebbington Citation2007; Borras Citation2016; Del Bene, Scheidel, and Temper Citation2018; Hall, Scoones, and Tsikata Citation2015; Olivera and Lewis Citation2004; Wolford Citation2004) that are not principally and exclusively agricultural in nature (Borras Citation2016). Agrarian struggles in the past three decades show the diversification of land struggles and the deepening of cross-class and multisectoral alliances around social struggles (Borras Citation2016, 13). The question then becomes: What is the weight and manifestation of agrarian structures in contemporary territory-based mobilisations? In what ways are they related to class positions and the differentiation rooted in agrarian political economy?

In search of answers, I focus on the struggles in northern Turkey against water grabbing for electricity production by small river-type hydropower plants (SHP) and delve into the question of agency in its multiplicity, hybridity and spatiality. The proliferation of SHPs provoked unprecedented resistance in the countryside in Turkey, offering a fruitful venue for the analysis of the contemporary political economy and social movements by crystallising myriad factors pertaining to crop regimes, livelihood structures and spatial transformations. I explore the changing forms of politicisation, agency, and class and cross-class alliances, as well as the discourses, symbols, and imaginations of the resistance.

My arguments in this article are built on the classic debate in political theory, ‘rationality, culture and structures’, and links to core debates in peasant studies on peasant mobilisations (Moore Citation1967; Paige Citation1978; Popkin Citation1979; Scott Citation1977; Skocpol Citation1994) and ‘When do peasants revolt?’ This has been discussed extensively in popular debates such as The Wolf-Paige debate and the Scott-Popkin debate about what sorts of peasants are revolutionary and the relative weight of economic and cultural determinants of peasant behaviour (Goodwin and Skocpol Citation1989; Kurtz Citation2000).

By the 1990s, the debate had become clustered around the ‘identity-oriented’ paradigm, new social movements (NSMs) and ‘resource mobilisation’ (Cohen Citation1985; McAdam, Tarrow, and Tilly Citation1996). NSM and subaltern studies put forward that agrarian mobilisation and resistance to capitalism/colonialism can be better explained by analysing the experience of gender/ethnicity, region, ecology or religion (Pahnke, Tarlau, and Wolford Citation2015). Scholars of NSM analyse the production of cultural meanings in political resistance (Alvarez, Dagnino, and Escobar Citation1998) and have privileged identity formation in mobilisation (Lindberg Citation1994; Polletta and Jasper Citation2001).

Recent literature on rural mobilisations also sparks a (sometimes fierce) debate on the existence and manifestation of class (Brass Citation2000; Petras and Veltmeyer Citation2018). Veltmeyer (Citation2019) puts forward that community and territory-based struggles carry class components due to circular migration, off-farm income diversification and diverse class positions. Similarly, Petras and Veltmeyer (Citation2019, 199) state:

The logic of the expansion of the new peasant movements in the 1990s was intimately related to the internal transformations of the peasantry – politically, culturally, and economically – as well as a dialectical resistance to the extension of neoliberalism and the encroachment of imperialism.

These observations point to a discrepancy in theory and literature on the question of agency in rural mobilisations. The revolutionary agency of the peasants as producers and their agency in today’s territory-based mobilisations with emphasis on culture and nature appear to be pioneered by ontologically different agents. Edelman (Citation2008, 251) states that ‘the first thing to acknowledge is that the campesino of today is usually not the campesino of even 15 years ago’. If they are indeed different, how are they related? The weight of structural changes in the peasant economy and its relationship to the transformation of agency from a historico-spatial perspective remains an area to be further explored. I argue that the past transformation of localities and peasant communities has an effect on the framing, discourses and strength of the resistance, and I take a spatial approach to tie the threads between two seemingly different forms of agency in rural mobilisations. The spatial approach is useful to bridge the political economic explanations of rural struggles, with political ecology and identity-oriented paradigms paying attention to both culture and human-nature interactions.

Building on critical geography, and particularly on Lefebvre’s (Citation1991) lived and abstract dimensions, I use space as the mediating ground and analyse its transformation to link the contemporary threats to ecology and rural livelihoods with past transformations in agrarian structures and the differentiation of the peasantry. A dual use of the space emerges, first in analysing the historico-spatial transformation of a locality in terms of production and livelihoods and second in how the meanings attributed to that space are interpreted and re-interpreted for the accumulation of capital and the resistance, focusing on agency, discourses and patterns of mobilisation.

Such an effort is not only empirically but politically necessary. Sevilla-Buitrago (Citation2015, 1002) states that ‘blending a comprehensive historico-geographical and theoretical viewpoint with a fine-tuned account of the spatial subtleties of specific practices of enclosure is not only analytically important but also, and especially, politically necessary’. Similarly, Borras (Citation2016, 13) calls for careful investigation of ‘broadening and deepening cross-class and multi-sectoral alliances around social justice struggles’. I argue that a comprehensive historico-spatial viewpoint can help to understand cross-class, rural-urban alliances and discover framing and resistance techniques that mobilise broader masses.

In this effort, I delve into resistance against water grabbing in Arhavi, a small town in northern Turkey, by placing it in the broader context of a historico-spatial transformation that began with the introduction of capitalist tea farming, followed by the privatisation of the river flow for electricity production, legitimised by green transition discourses. I argue that one of the major contributors to the strength of the mobilisation in Arhavi is the intensity of rural-urban linkages, which facilitated broader coalitions and cross-class alliances. This was made possible by the upward mobility that has emerged due to the prior characteristics of rural-urban migration and the state-supported dominant crop system. This came within the developmentalism of pre-neoliberal state policies, which brought about a group that I call ‘urban middle classes with peasant characteristics’ inspired by the work of Ricardo Jacobs (Citation2018).

The involvement of better-off urban actors in environmental/rural mobilisations is discussed in the literature (Arsel, Akbulut, and Adaman Citation2015; Hobsbawm Citation1974; Kavak Citation2021; Kerkvliet Citation1993). My previous work (Kavak Citation2021) presentsan analysis of upward mobility in Arhavi as a contributing factor to the strength of the resistance through a cross-comparison of four cases, which is important to demonstrate the role of the rural class structure in mobilisation and the resistance techniques particular to certain classes, such as the role of abstraction. However, the article presents limited evidence and scrutiny on the emergence and the specificities of the urban middle-class involvement in the struggle nor offers a conceptualisation on it going beyond the rural/urban dichotomy. Moreover, it also demonstrates that the middle-class involvement in other villages could not bring about a strong mobilisation, signalling a difference in middle-class involvement per se. In this article, I develop my previous work and propose a conceptualisation of ‘urban middle classes with peasant characteristics’ as a hybrid group with strong mobilising potential that possesses features different from environmentalist middle-class urbanites due to the uninterrupted engagement with rurality through tea farming, a typical peasant activity. I demonstrate how historical links to the land, combined with long-term urban residence and upward mobility, connect to rural struggles in a context where land dispossession did not take place to a large extent.

1.1. Materials, methods and organisation

This article is based on data collected through a qualitative case study design focusing on the water struggle in Kamilet Valley in Arhavi. The area was chosen because it is located in the Eastern Black Sea region, which is a rich region in terms of river flow and precipitation, thus it is where a large number of SHPs were licensed. The area is going through intense commercialisation limited not only to SHPs and the commercialisation of water but also through mining activities and the commercialisation of tea and hazelnut production. Exemplary cases of persistent and strong mobilisations have risen from this region (Kavak Citation2021; Yavuz and Şendeniz Citation2013). Precipitation rates are higher than the country average and the region is mountainous, making the region attractive for energy companies. As the region is relatively socially, historically, and geographically homogeneous, the resistance in Arhavi can be considered representative of the broader Eastern Black Sea region.

The anti-SHP struggle in Arhavi can be divided into two phases, the first was initiated by locals and was eventually co-opted by the SHP company, while the second was revitalised by city-based protestors with stronger mobilisation capacity. Hence Arhavi as a case study enables simultaneous observation of city and village-based agencies. I followed the struggles in Kamilet Valley over time, between 2012 and 2017, until the SHP was built and began operation. I conducted field research in the village between August 2013 and November 2014, which was composed of in-depth interviews (n = 17) and focus groups. Moreover, I interviewed activists and locals in the neighbouring valleys of Arılı, Çoruh and Hopa (n = 15) to learn about alliances, coalitions, perceptions and strategies. I collected data through media scanning, social media pages, attending resistance group meetings in Istanbul, and secondary resources. Each visit lasted one month and I regularly followed the course of events in each case throughout the whole period – including the lawsuits, resistance campaigns, demonstrations, and media coverage. The data collected from the villages constitute the major data source. At the time of the fieldwork in Arhavi, the resistance was strong and the lawsuit was ongoing. Interviewees were selected through snowball sampling and conducted in the houses and courtyards of the peasants, in orchards, in coffee houses, and in SHP construction sites. The struggle failed in 2018 after a lengthy on-site and legal battle. Nevertheless, this outcome can be attributed more to an increasingly authoritarian political environment in Turkey, within which pro-government capital groups enjoy strong crony ties. The protestors face limitations in various ways due to diminishing separation of powers. Regardless of the outcome, Arhavi witnessed one of the strongest anti-SHP mobilisations in the country.

In the next sections, I elaborate on the livelihood transformation and upward mobility enabled by state-supported tea production, rural-urban linkages, and how spatial imaginaries and place framing translate into collective action. Furthermore, I link the class position of the protestors to the spatial changes within the locality in the last 70 years. I demonstrate how prior changes in the agrarian structure brought about a social group, ‘middle class with peasant characteristics’, that had constant ties to the village both materially and culturally.

2. Small hydropower development in Turkey, environmental mobilisations, and the case of Arhavi

An SHP grants the right to the water that flows in a river basin to private companies for 49 years. In run-of-river hydropower plants, water in the riverbed is channelled through a canal and carried to a penstock to power a turbine, after which it is released back into the riverbed. In the absence of institutionalised regulations, it can end up taking too much water from the river, even drying some parts of the river or destabilising the natural river flow resulting in floods. In authoritarian neoliberal Turkey (Borsuk et al. Citation2021; Kutlu Citation2021), SHPs have become sites of primitive accumulation with rents distributed between the government and cronies.

The political economy of SHPs in Turkey is multifaceted and can be analysed from various perspectives, shedding light on the relationships between state and bourgeoisie, state and civil society, and accumulation and global political economy (Erensu Citation2011; Citation2013; Citation2018; Harris and Işlar Citation2014; Işlar Citation2012). Anti-SHP mobilisations in Turkey are frequently analysed as ecological movements with cultural undertones but there is a growing literature on the actors of mobilisation and livelihoods (Erensu Citation2011; Citation2013; Işlar Citation2012; Yavuz and Şendeniz Citation2013). Arsel, Akbulut, and Adaman (Citation2015) point out how today’s rural mobilisations cannot be analysed within the duality of the materialist vs post-materialist explanations or only by environmentalism but by the long-lasting dissatisfaction with broader processes of state-led neoliberal developmentalism combined with the personal activism of a group of urban, mostly retired, residents collaborating with peasant activists. Knudsen (Citation2015) is also sceptical about the claim of environmentalism as the ‘unifying’ discourse that marks the emergence of non-state actors in contemporary mobilisations in Turkey and opposes the contention shared by activists and some NSM scholars that ‘environmentalism’ offers a new avenue for mobilisation ‘above politics’.

Even though not necessarily focusing on environmental movements, Tugal (Citation2015) opens up channels for class analysis in the re-theorisation of social movements through his critique of liberal-democratic and NSM actors in the post-1980 era. He focuses on the role of the new petite bourgeoisie in multi-class revolts like the Gezi Revolt,Footnote1 which are anti-commodification in form and against the alienation of the commons. He distinguishes new petit bourgeois activism with spirits of creativity and an aestheticisation of resistance. The question of ‘who acts?’ nevertheless still remains a critical point to be answered in the Turkey-specific literature. In the next section, I elaborate on the peasantry transformation in Arhavi to demonstrate how it connects to rural mobilisations with environmentalist outlooks.

2.1. Tea economy, peasant households and outmigration in Arhavi

Arhavi is a coastal town in the Eastern Black Sea region, founded along two valleys originating from the high and steep mountains of Eastern Anatolia. The climate is a typical example of the Eastern Black Sea region, characterised by an abundance of rainfall and mild temperatures, making the region suitable for the production of tea and hazelnuts. Due to the scarcity of cultivable land and the rainy climate, the region has long been peripheral, with prevalent poverty and the circular migration of men (Clay Citation1998). However, the marginal position of the Eastern Black Sea region changed drastically after the 1950s with the introduction of tea as a cash crop as a state-led regional development project. The state had a monopoly in the purchase and processing of tea and encouraged its production with generous support policies. Peasants adopted tea production rapidly, and tea assumed the character of monoculture as peasant households abandoned hazelnut production. The burgeoning tea industry created jobs for men in factories and women as field workers. Many families became prosperous and hired day labourers, while other sectors such as construction and commerce also grew (Hann Citation1990). Arhavi gained the reputation of ‘little Istanbul’ due to its prosperity (Hann and Beller-Hann Citation1998) in . State involvement during the import-substitution industrialisation strategy resulted in the creation of hundreds of jobs in local administration, health and education, which offered long-term security and pension.

Recent academic literature on state, society and politics in Turkey goes beyond the prevalent analyses of top-down economic interventionist measures in the region. Rather, the tea economy enabled rural/provincial populations to negotiate their interests with the political authority throughout Republican history (İnal and Saraçoğlu Citation2022) including during the neoliberalisation of cash crop production in the 2000s which resulted in the return of agricultural subsidies and social assistance (Gürel, Küçük, and Taş Citation2019). Historically, the tea economy granted significant ideological appeal for the Justice and Development Party (AKP) in the region through its role in nation-building, but it also engendered an arena for negotiating citizenship rights as well as economic interests. Though beyond the scope of this article, this arena enabled strong mobilisations and negotiations in the region, including during the struggle in Arhavi.

Despite the burgeoning tea economy, outward migration continued during the import-substitution industrialisation period. Migration from Black Sea provinces began earlier than in other regions because of pressures on the agricultural economy (Munro Citation1974), Primary rural-urban migrations took place in the villages where the cultivable land reached its limits and connections to the urban areas highlighted better job opportunities and services in the cities (Akşit Citation1998).

According to statistics published on the official website of the town of Arhavi, the city has a population of 15,901, with 4,405 in rural areas. However, there are significant seasonal differences in the population of the villages. The agricultural production statistics of the Turkish Statistical Institute in 2012 state that tea fields covered an area of around 26,500 acres and hazelnut fields around 12,500 acres, whereas corn, the traditional crop produced in the region, covers only around 3,200 acres (TURKSTAT Citation2012).

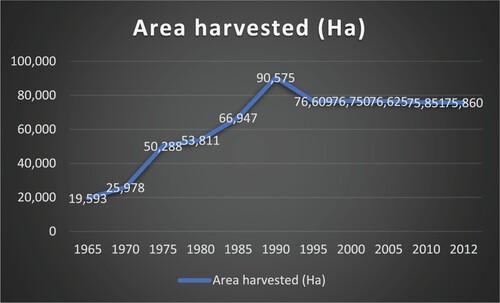

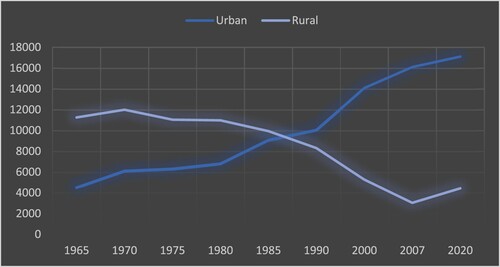

Footnote2 shows that the area cultivated sharply increased from 1965, reaching its peak between 1985 and 1990, after which it stabilised at around 70,000 hectares when tea production reached its natural limit and the area became a monoculture (Hann Citation1990). Notably, there is a stark positive correlation between the population figures and migration trends in the region. shows the rural-urban levels of population change in Arhavi, where we observe gradual depeasantisation in the town despite the increase in the area cultivated for tea production.

Figure 2. Proliferation of Tea Farming in Turkey. Source: Food and Agriculture Organisation Country Statistics.

Figure 3. Rural-Urban Population Figures in Arhavi, Source: TURKSTAT (Citation2016).

Rural-urban levels became equal around 1985–1990, the period in which the tea fields reached their maximum area of cultivation. The slight rise after 2008 can be attributed to the effect of the economic crisis and voluntary repeasantisation. The 2007 census shows that around 30,000 people registered in the province of Artvin (where Arhavi is situated) actually lived in Ankara, 57,000 in Bursa, 76,000 in Istanbul, and 9,900 in Izmir, the four metropoles of Turkey.

Commercial tea production resulted in outmigration and depeasantisation in Arhavi, even though the area cultivated for the cash crop increased significantly. This depeasantisation did not stem from a loss of livelihood but rather household capital accumulation facilitated by state-supported tea production. Tea bushes are perennial plants with an average life of 100 years. Since the rain level in the region is high, they do not require irrigation. Therefore, the crop does not need yearlong care and harvest during the summer is sufficient. Cultivation does not require long-term, intensive labour, and the land owner’s presence in the region for four-to-five months is more than enough to harvest and sell the crop. Tea production is thus suitable for pluriactivity. Tea and hazelnut farming is also more profitable compared to most of the other crops cultivated in Turkey, yielding income that can supplement household income regardless of the place of residence. Nevertheless, an interviewee states:

There is agriculture but it is not enough. Income from tea is not enough anymore. You have to collect 1 t [tea leaves] to earn 1,250 Turkish lira. Half of it will be spent on workers. We are seasonal workers, we come here in summer to collect tea leaves. It [tea income] is not flowing but it is dropping, it is better than nothing.

Peasants who stayed in the villages diversified their household income by working in tea processing units and tea factories, albeit seasonally, and also by opening coffee houses and grocery shops. This is a general pattern for tea and hazelnut producers of the Black Sea region in Turkey (Gürel, Küçük, and Taş Citation2019). Since agricultural producers benefit from a special retirement scheme, there are retired people in the household too, supplementing farm incomes.

Independent of the differential integration into the city economy, the social and economic meaning of land has been altered. Benefiting from accumulation facilitated by the generous state support for the tea economy, many families from the villages of the coastal Black Sea became upwardly mobile in the city and shifted to middle-class status, becoming urban middle classes with peasant characteristics. They retain peasant characteristics because they spend several months of the year in the village during the tea harvest and preserve their local culture. The societal implications of this become more lucid in the analysis of anti-SHP resistance as presented in the following section.

2.2. Anti-SHP resistance in Arhavi

MNG Holding, which is one of the major capital groups in Turkey and whose owner is a pro-government businessman from Arhavi, started the construction of Kavak SHP in Arhavi. The construction encountered resistance from the locals of the three villages that were to be affected by the SHP. The power plant was planned to be situated in Arhavi town centre with the water collected from Kapistre and Çifteköprü Rivers via tunnels and a canal from the mountains and villages around five kilometres away. MNG Holding was granted the construction permit for the power plant in Arhavi by the municipality of Artvin even though there was a legal case calling for the suspension of the project due to an infraction of rules and regulations in the preparation of the environmental impact assessment (EIA).

The struggle in Arhavi took place in two phases. The first began in May 2012 with the launch of the primary phases of the project, when resistance was evoked in the villages affected by the construction where the plans foresaw pulling down houses along with land expropriations: Kemerköprü, Kavak and Konaklı. The events in the summer of 2012 are remembered as a total struggle of everybody living in the three villages including the village heads, muhtars. As mentioned above, lower-class village dwellers are composed of pluriactive tea-producing households, with one or more members working in some service sector job or seasonally in tea factories, and usually with one pensioner.

Protestors founded a resistance tent by the riverside and the struggle continued for about three-to-four months before eventually fading away. This phase of the resistance was less widespread and more local than the following wave. The gradual decline of the resistance was attributed to the company’s negotiations with some protestors, families and village heads to co-opt the struggle. One major step in this move was the subcontracting of construction to a company from the village, and supporting the owner to be elected as the village head in the municipal elections and therefore a natural, clientelistic ally for the company with local executive power. Another strategy of the company was to offer employment in various positions in MNG Holding to some of the protagonists of the struggle.

A villager who was working as a security guard on the construction site of the SHP at the time of the interview openly defended his pro-company position by stating:

We struggled a lot here. Then the company came and promised to build a facility, a mosque. They might even build a school. And we discussed and told the company [representatives] that we want our youngsters to work in construction with formal insurance and minimum wage. Why should an outsider come and work here? It would provide jobs for our own youngsters. They accepted. (…) I will be retired once I earn the right. Is it bad? And now I look around and think that this SHP is not really damaging nature.

Yes, unfortunately, they do. Especially the younger people. Some people at the age of 35 have never registered with social security. Also, here, most people work in the tea factories seasonally, between May and September. Between September and May, they just wander around. They have health insurance just for six months. Thus, they are easily attracted to the offers [of the company]. Those who stay firm are financially better off.

Water is at the centre of commercialisation, but land is also a contentious area between the companies, the state and the local people. Land is critical in terms of its value as a means of production as well as its exchange value. Moreover, it became a strategic tool for locals to resist the company as well as a tool for the company to co-opt the resistance. The effectiveness of the co-option strategies of the company and the resistance strategies of peasants varied according to the economic function of land in their village. The main quality of land as the primary means of production has been compromised by the decline of the profitability of the tea economy and outmigration from villages. The land is thus rendered a mere commodity for most people, with an exchange value, for which the SHP created a market.

Two brothers go to Istanbul and persuade their relatives (to sell the land) but tell the villagers that the relatives in Istanbul wanted to sell it and they had to comply with it. They sell the land for 250–300 thousand TL; that would actually be worth 40–50 thousand.

3. Revival of the struggle and urban middle classes with peasant characteristics

Urban middle classes with peasant characteristics is my conceptual reinterpretation of Ricardo Jacobs (Citation2018) influential work on the urban proletariat with peasant characteristics. He builds this to explain the curious case of Zabalaza land occupations, in which people combine urban wage labour and livestock farming: ‘their diverse ties to the land that reflect the peasant character of the urban proletariat, their diverse ties to wage labour are indicative of their proletarian character’ (Jacobs Citation2018, 891). The work is important and inspiring for its scrutiny of proletarianisation and class formations in the context of agrarian change. Jacobs offers a comprehensive critique of the linear approaches to proletarianisation and disputes the contention that urbanisation/proletarianisation has dissolved the ‘peasant outlook’ or eliminated their underlying demand for land for agricultural pursuits, which is not the case for the Zabalaza farmers, whose livelihoods depend on livestock farming.

Acknowledging that urbanisation and proletarianisation may result in the weakening of economic and social/cultural ties to rural areas, the work shows that there are many shades of urbanisation and agrarian class change that engender diverse subjectivities and strong political mobilisations. My conceptualisation of middle classes with peasant characteristics is based on three pillars: (1) uninterrupted historical links to the land through tea farming for a certain degree of income to support material livelihoods, (2) long-term residence and jobs in urban areas, and (3) the tendency to associate or self-identify with peasantness and recreate it with an emphasis on the particular local traditions. In this regard, I combine material and immaterial factors, hence the structures and the culture, in my conceptualisation. Even though the share of farm income for the urban middle-class group under scrutiny is not as important as for the Zabalaza community, the retention of social and cultural ties to the locality is maintained through uninterrupted links to the land and the importance of tea income across at least three generations of household accumulation.

As scholars of critical agrarian studies have long demonstrated, agrarian and urban societies mutually constitute each other in myriad ways (Edelman Citation2008). The political and cultural economy of production and accumulation requires an in-depth understanding of diverse types of relationships and tensions between the countryside and the city. Earlier analyses focused on leadership, generally stressing the importance of outsiders or the emigration of local notables, often from dominant classes or groups, to help the villagers understand their situation, provide guidance for what to do and how, and assist in mobilisation for organisation and alliance building (Hobsbawm Citation1974; Kerkvliet Citation1993). Wolf (Citation1969) made the case that ‘middle peasants’ were the main rural activists, having established links to the urban sector by engaging in, or having family in, non-agricultural economic activities such as construction, transport and trade. In a similar vein, Petras and Veltmeyer (Citation2011) state that the new peasantry, especially those who led the struggle, travelled to the cities, participated in seminars and leadership training schools, and engaged in political debates. Even as they were rooted in the rural struggle, lived on land settlements, and engaged in agricultural cultivation, they had a cosmopolitan vision. Recently academic attention has turned to struggles of indigenous communities both in rural and urban areas enabled by common indigenous identity and rural out-migration (Sobreiro Citation2015). However, in the case of Arhavi, we see a more mutually constitutive and hybrid relationship between the city and the countryside. The increase in the interdependency and mobility between rural and urban spaces resulted in the constitution of new multilocal livelihood strategies and identity formations.

The majority of the population in Arhavi either lives outside of Arhavi, in metropoles such as Istanbul and Ankara, or owns a house in the centre of Arhavi. What unites them is their return migration to the villages during the summer, for short holidays, and especially during elections. Moreover, those who have settled back into the village after working outside for years, or those who live in the villages while owning a business in the city, plays an important role in the resistance.

During the field research, I observed that most of the protagonists of the struggle were either retired people who had moved back to their village after working in the cities, or people who were still working in the city with formal employment, career plans and consumption patterns that might be evaluated within the paradigms of the middle class or more specifically new middle class. One interviewee’s response to a question on the villagers and the leading figures of the resistance is telling: ‘We tell that the villagers are struggling but, in fact, those who are actively in struggle are the more educated, elite ones’.

A prominent person in the resistance, living in a nearby village, stated that he had been living in Izmir for a long time and owned a company there, but had returned to his village recently. Another couple had moved back to the village after running a business in southern Turkey, having renovated a traditional wooden house inherited from their grandparents. One of them stated, ‘I am 52 years old, I did not know what SHP was. When we arrived, I was busy with the house, with the restoration etc., so I did not feel the need to go to the resistance tent’.

Avcı (Citation2017) stresses the transformative role of environmental struggles on the construction of political subjectivities. It is important to acknowledge the transformative role of the Gezi Revolt on the politicisation of urban dwellers, particularly the youth, concerning environmental issues and government policies. Growing sensitivity and the desire to take over the resistance in Arhavi after the initial phase can partly be accounted for by this wave of politicisation and mobilisation. Looking retrospectively at the initial phase, the new group of protestors stated that the struggle was co-opted more easily because most of the protagonists of the later phase were not living in Arhavi back then. Another reason they put forward is the media and the general public’s lack of interest towards ecological problems, already marking a discursive shift from the rhetoric of the initial phase by emphasising ecological concerns.

One leading figure is a financial consultant residing in Ankara, while the other returned to the village after working in Istanbul for several years. During a focus group interview at the end of summer 2013, some other leading members of the struggle were discussing the dates of return to their homes all around the country:

Four households stay in the village during the winter. There are those who also move to Arhavi [town centre]. In Kavak village, around 15–20 households stay as well. During the summer, there are around 70 households in every village. People all leave in the wintertime. They sometimes come back for the weekends. (…) Then we have all gone back to Istanbul etc. for the election periods. We returned on the 18th of August and the court declared suspension of the implementation of the project on the 19th. The next day. they left [the construction site]. It was the time that we were most crowded with those who had returned for the summer and had come for the festival. They [the company representatives] could not take the risk and left. We organised a big vigorous demonstration in the town centre.

3.1. Cross-class alliances and mobilisation capacity

The following vignette demonstrates the mobilisation capacity of the villagers in Arhavi:

Everything began with this bridge. The construction of this bridge meant the demise of the opponents. (…) As the company went on [with construction], the public withdrew from the opposition thinking that they could not stop [the construction] anyway. Then, we won the lawsuit. Until then we were ten people [in the struggle], but after the court decision 110 people gathered … Hundreds of people we did not know came to congratulate us. [They were] from Arhavi, from the villages. Brother, where were you? Anyway, it is a nice thing but many of us asked where were you when we were in a struggle, but we won the case. From now on, they will think if those people won this lawsuit, they may also win others. So, they can support us and persuade other people to support us.

Resistance in Arhavi has organic links with the townsmen organisations. The Istanbul Association of Arhavilites (İstanbul Arhavililer Derneği), the Ankara Association of Arhavilites (Ankara Arhavililer Derneği), the Association of Businessmen from Arhavi (Arhavili İş Adamları Derneği) and the Foundations of Arhavilites (Arhavililer Vakfı) are integral components of the resistance. This is an indicator of the hybrid spatial construction and strong connection between the city and the countryside. During the mobilisation, these organisations arranged demonstrations and solidarity events both in Arhavi and in the cities, Ankara and Istanbul in particular. The following quotation highlights the structure of agency in the struggle of Arhavi:

The expert investigation took place on the 28th of January. We came here one week before it. We thought that we should be crowded for the expert investigation. The Association of Arhavilites arranged two buses from Istanbul. People came from there. The Foundation of Arhavilites arranged one bus from Ankara. 1,500–2,000 people gathered in the Cumhuriyet Neighbourhood. We did not expect that much. It was very effective, reassuring. We also organised a demonstration in Istanbul and the crowd there was not bad at all.

After the municipal elections of 30 March 2014, the protagonists depicted above were left alone, in their own words. The events that followed are marked by the legal case and the attempts of the most active people to support the legal struggle. They established the Platform for Protection of Nature in Arhavi, a small gender-based collective named Female Hawks of Arhavi, and another ‘resistance tent’.

The tent that was situated near the main construction site served as a space of resistance for the people from Arhavi as well as other anti-SHP activists across Turkey. Prominent activists were invited to give talks on the environmental destruction caused by SHPs. Leading figures of the anti-SHP resistance of Fındıklı and the city-based environmentalist platform Black Sea in Revolt (Karadeniz İsyandadır) joined the group for solidarity and support. In the meantime, influential environmental lawyers took on advocacy of the case.

Protests, sit-ins, demonstrations and media outreach were carried by the protestors. However, in the background, the legal struggle continued. As public incentives for the proliferation of SHPs and cronyism, licensed SHPs mushroomed, but with significant neglect for the environmental and societal consequences. EIA requirements are the main means to monitor the environmental consequences of projects, as well as the main realm in which legal irregularity transpires. The most effective way to challenge SHPs is thus to focus on the accuracy and appropriateness of EIAs.

An EIA report is a requirement for project implementation, prepared by authorised independent institutions. The Ministry of Environment and Urban Affairs holds the authority to approve EIA reports prepared for individual projects, together with the right to grant EIA exemption for some projects. Hence, the impartiality of the EIA processes is seriously compromised. Legal battles take place predominantly on the grounds of conflicts on EIA exemption and improper EIA preparation and implementation. Courts often rule that projects should be suspended as a result of improper implementation of the EIA bylaw but a company’s water usership rights or energy production licence are seldom annulled. The company can then renew its EIA reports and continue with the construction. Needless to say, the court process is long and expensive. Locals are stuck between the energy companies backed up by state policies and an increasingly centralised governmental authority that bypasses the formal separation of powers.

In Arhavi, upon the exploration of the project zone, experts discovered that there were severe infractions in the project design and also in the EIA reports. There was fraud in the measurements of the flow rates, the catchment area was not planned accordingly and construction waste was not disposed of according to the criteria. With pressure from lawyers and those who resisted the SHP, an expert witness provided the court with a report declaring the ill-implementation of the project. Eventually, the court decided to suspend the project and annul the EIA report, and later completely annulled the project during the summer of 2015. However, the legal battle continued and the SHP was constructed in the meantime. In 2018, after six years of struggle, the power plant started producing energy and the river lost most of its flow.

3.2. Aesthetics of resistance: symbols and traditions as mediators of the mobilisation

The concrete abstraction of spaces is a concept extensively theorised by Lefebvre (Citation1991) and Soja (Citation1996). Even though the literature primarily implies that the abstraction benefits capitalists, the abstraction and reinterpretation of spaces can also be used by the residents and ex-residents of a particular locality. Abstract space is the space of ideas, images and symbols reflected in a particular space. It constitutes a major frontier for resistance against commercialisation at a time when capitalism relies on the marketisation of collective wealth to overcome intensified crises of accumulation (Hardt and Negri Citation2009), and abstract space emerges as a critical component of struggle (Sevilla-Buitrago Citation2015). This observation materialises in Arhavi, where the abstract space also becomes a battleground for those who fight against SHP constructions, especially the urban middle classes with peasant characteristics.

Abstraction of space helps protestors, mostly those who live in the cities, to reimagine the villages they or their parents come from through symbols and authentication, to revive the peasant identity. Every summer, since 1973, a festival has been organised in the town centre, which constitutes a space for interaction between the townsmen and also serves the abstraction of the space. The festival programme includes competitions in tea harvesting, hazelnut shelling, cooking traditional dishes such as anchovy bread or laz böreği, and carpentry. The festival has the social function of creating attachment to the rurality and preserving the societal imagination of being a part of, and social and cultural ties to, the village.

Collectively, the protestors contributed to the abstraction and reconstruction of the spaces and the struggle was strengthened through those strategies. Symbols and defence concepts were used abundantly. One example is the personification of the river and making it an active part of the struggle through remembering; memory, culture and traditions appear as key elements of the construction of symbols and defence concepts. Another is the rediscovery of local-historical particularities and their intensive use in the discourse and organisation of the resistance to create a common attachment to the locality of origin together with a distinct identity of the region, which is a form of ‘re-invention of tradition’ (Hobsbawm and Ranger Citation2012). It is a re-invention of tradition because the agents who became urbanised by migrating to the big cities and became the middle classes are, so to say, cleaning the dust off the local traditions and symbols. This effort did not occur as a mere resistance strategy, but as a part of identity construction through which the protestors re-established links with the locality and peasantry.

Furthermore, they were able to mobilise other people from the locality as well as the broader public around the same cause. Aestheticising the resistance through novel symbols and dusted-off traditions proves to be an effective strategy in building alliances between the rural and urban and between classes. An active member of a city-based environmental organisation, Karadeniz İsyandadır, said during an interview that he remembers the day when the yellow scarf (sarı yazma) emerged as the symbol of the anti-SHP resistance in the Loç Valley. The yellow scarf was extensively used in flyers, banners and other propaganda material. The struggle of the sarı yazma became the defining element of the news on the anti-SHP struggle of the Loç Valley in Kastamonu.

We observe a similar pattern in the anti-SHP struggle of Arhavi. With the revival of the struggle, the hawk emerged as the symbol both to depict the strength of the resistance and to emphasise a common history, since training hawks for hunting used to be a widespread cultural practice. It also symbolised unity with nature and attachment to a particular geography. shows a photo taken by the Istanbul branch of the Platform for the Protection of Nature in Arhavi during an anti-SHP protest in Istanbul.

Figure 4. Banner reading ‘Do not touch the rivers of Arhavi, do not anger the hawk’. Source: http://www.bianet.org/bianet/toplum/153699-arhavi-nin-dereleri-istanbul-a-akti.

The strong organisational capacity of the Istanbul branch of the Platform underpins the argument on the multi-spatial nature of their agency. Many of the protestors lived in Istanbul and Ankara and continued their struggle in the city, either in iconic urban spaces known for emancipatory protests or in front of the headquarters of MNG Holding. During a demonstration in front of the company headquarters, the protestors wore hawk masks representing the anger, strength, culture and dignity of the people of Arhavi. Over time, the symbol of the hawk became widespread, constituting an identity not only for the protestors but also for the people of Arhavi. The name of the resistance collective changed to Hawks of Arhavi, Arhavili Atmacalar, and social media pages and profile photos are dominated by photos of hawks.

A group of not more than ten women who struggled against the SHP named themselves the Female Hawks (Kadın Atmacalar) and appeared in national and local media. One member is a journalist and another is a financial adviser, both of whom live in Istanbul. Some others live in the Arhavi town centre and some returned to their village after working in cities. The hawk went beyond being just a defence symbol, it became an identity, especially for the urban middle classes with peasant characteristics. What is even more striking is the staging of this very re-invented identity in a carnivalesque manner, in an aestheticised form of dissent. Photos in the river that captured women like warriors were published and circulated widely in the national media.

Hence, a close analysis of the case of Arhavi provides us with an understanding of how the abstract space is instrumentalised in the framework of resistance movements, especially in hybrid spaces like rural Arhavi.

4. Conclusion

Contemporary rural structures show complex variations emerging from spatial configurations, which raises the question of who acts in contemporary movements in the countryside. Ecological destruction is a facet of spatial change, together with the livelihood transformation altered by the changes in agricultural production. We witness novel forms of political resistance, which manifest broader class alliances, distinctive discourse and innovative framing methods.

The case of Arhavi allows us to analyse the historical and spatial dimensions of agency in territory-based mobilisations, where the tea economy fostered under state protection made an important contribution to the strength and framing of the resistance. I put forward that the outmigration and upward mobility facilitated by tea production during the long course of agrarian change in the twentieth century affect the politicisation and collective resistance in the hometown today. This happens thanks to the constant movements between the urban and the rural, constantly combining rural and urban sources of income; again, eased by tea cultivation. Moreover, I suggest that the integration levels in the city, the socio-economic position attained in the city, and former politicisation in the city have also affected the strength, course and strategies of the struggle by urban middle classes with peasant characteristics.

Urban middle classes with peasant characteristics are a product of historico-spatial transformation. They live in big cities in Turkey, work in middle-class jobs and are part of the urban economy and lifestyle. However, they regularly spend a couple of months in their village during the tea harvest, gathering with their elderly and extended families; they are parts of the village. Most of them also frequently visit their village throughout the year. They harvest and sell the tea during summer, and return to the city with their share of the tea income.

They are members of township organisations in the city. It is common for rural migrants to have township, even village-based, organisations in the cities in Turkey. In the case of Arhavi, the fellow townsmen are organised in foundations, associations, and business organisations, as household accumulation enabled many families from Arhavi to become entrepreneurs in the city. Therefore, the link with the village and the sense of belonging to the village is a constant for many people from Arhavi, which is also true for the younger generations born and raised in the city.

Moreover, I put forward that material transformations impact the conceived transformations of the space, and how particular spaces are reconstructed, imagined and represented. Thus, a dual pattern emerges in the analysis of the historico-spatial transformation of a locality and how it is interpreted and re-interpreted for capital accumulation and also for resistance. Scrutinising the actors of the resistance and the relations between them provides insights into the new political actors and mobilisation patterns in the countryside. Detailed analysis of the resistance in Arhavi points to the strength of middle-class actors with peasant characteristics, who simultaneously possess social/cultural and economic ties to rurality and the urban middle class configuration. They benefit from cultural capital, new discourses and aestheticisation together with broader coalition-building capacities. These actors are products of both agrarian change and contemporary resource-grabbing. In this sense, the case of Arhavi is emblematic in showing that the political economy and political ecology approaches to territory-based mobilisations are two faces of the same coin.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sinem Kavak

Sinem Kavak is a political scientist specialising in critical political economy and political ecology. She earned her Ph.D. in 2017 from Institute des Sciences Sociales et du Politique in École Normale Supérieure de Paris Saclay and Boğaziçi University in the framework of a joint PHD agreement. Her research areas include agrarian change, territory-based social movements, water grabbing, migration and labour. Her work appeared in Journal of Agrarian Change and New Perspective on Turkey among others. Currently, she is a researcher at Lund University and her current research focuses on the impacts of climate change and politics of climate change on migrant farm workers.

Notes

1 The Gezi Revolt was a widespread mobilisation in Turkey in 2013 that began as a reaction to an urban development project in a city park in Istanbul. It represented a powerful grassroots mobilisation by bringing together people from different class, social, ethnic, ideological and cultural backgrounds against the authoritarian neoliberal policies of the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP).

2 Although this chart is based on changes in the aggregate area of tea cultivation in Turkey, the trend is representative to that of Arhavi, as tea can only be produced in the warm and rainy climate of the coastal Eastern Black Sea region.

References

- Adaman, F., and M. Arsel. 2010. “Globalization, Development, and Environmental Policies in Turkey.” In Understanding the Process of Economic Changes in Turkey: An Institutional Approach, edited by T. Çetin, and F. Yilmaz, 319–335. New York: Nova Science Pub Inc.

- Adnan, S. 2013. “Land Grabs and Primitive Accumulation in Deltaic Bangladesh: Interactions Between Neoliberal Globalization, State Interventions, Power Relations and Peasant Resistance.” Journal of Peasant Studies 40 (1): 87–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2012.753058.

- Akşit, B. 1998. “İç Göçlerin nesnel ve öznel toplumsal tarihi üzerine gözlemler: Köy tarafından bir bakış.” In Türkiye’de İç Göç, Sorunsal Alanları ve Araştırma Yöntemleri Konferansı Bildiriler Kitabı, 22–37. Istanbul: Tarih Vakfı Yayınları.

- Alvarez, S., E. Dagnino, and A. Escobar. 1998. Cultures of Politics, Politics of Cultures. Boulder: Westview.

- Arsel, M., B. Akbulut, and F. Adaman. 2015. “Environmentalism of the Malcontent: Anatomy of an Anti-Coal Power Plant Struggle in Turkey.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 42 (2): 371–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2014.971766.

- Avcı, D. 2017. “Mining Conflicts and Transformative Politics: A Comparison of Intag (Ecuador) and Mount Ida (Turkey) Environmental Struggles.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 84: 316–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.07.013.

- Baviskar, A. ed. 2007. Waterscapes: The Cultural Politics of a Natural Resource. New Delhi: Permanent Black.

- Baviskar, A. 2017. “What the Eye Does Not See: The Yamuna in the Imagination of Delhi.” The SAGE Handbook of the 21st Century City, 298. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526402059.n16.

- Bebbington, A. 2007. Minería, movimientos sociales y respuestas campesinas: una ecología política de transformaciones territoriales (Vol. 2). Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos.

- Bianco, L. 1975. “Peasants and Revolution: The Case of China.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 2 (3): 313–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066157508437938.

- Borras, S. M. 2016 (April 14). “Land Politics, Agrarian Movements and Scholar-Activism.” Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/1765/93021.

- Borras, S. M., J. C. Franco, S. Gómez, C. Kay, and M. Spoor. 2012. “Land Grabbing in Latin America and the Caribbean.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 39 (3–4): 845–872. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2012.679931.

- Borsuk, I., P. Dinç, S. Kavak, and P. Sayan. eds. 2021. Authoritarian Neoliberalism and Resistance in Turkey: Construction, Consolidation, and Contestation. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Brass, T. 2000. Peasants, Populism and Postmodernism: The Return of the Agrarian Myth. London: Frank Cass Publishers.

- Clay, C. 1998. “Labour Migration and Economic Conditions in Nineteenth-Century Anatolia.” Middle Eastern Studies 34 (4): 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/00263209808701241.

- Cohen, J. L. 1985. “Strategy or Identity: New Theoretical Paradigms and Contemporary Social Movements.” Social Research 52 (4): 663–716.

- Corson, C., and K. I. MacDonald. 2012. “Enclosing the Global Commons: The Convention on Biological Diversity and Green Grabbing.” Journal of Peasant Studies 39 (2): 263–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2012.664138.

- De Angelis, M. 2007. The Beginning of History: Value Struggles and Global Capital. London: Pluto.

- Del Bene, D., A. Scheidel, and L. Temper. 2018. “More Dams, More Violence? A Global Analysis on Resistances and Repression Around Conflictive Dams Through co-Produced Knowledge.” Sustainability Science 13 (3): 617–633. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-018-0558-1.

- Edelman, M. 2008. “Transnational Organizing in Agrarian Central America: Histories, Challenges, Prospects.” Journal of Agrarian Change 8 (2–3): 229–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0366.2008.00169.x.

- Erensu, S. 2011. “Problematizing Green Energy: Small Hydro Plant Developments in Turkey.” ESEE 2011 Conference, Istanbul, 14–18. Available at: http://www.academia.edu/download/31024000/esee2011_c36142_1_1307137792_1401_2288.pdf.

- Erensu, S. 2013. “Abundance and Scarcity Amidst the Crisis of ‘Modern Water’: The Changing Water-Energy Nexus in Turkey.” In Contemporary Water Governance in the Global South: Scarcity, Marketization and Participation, edited by L. M. Harris, J. A. Goldin, and C. Sneddon, 61–78. New York: Routledge.

- Erensu, S. 2018. “Powering Neoliberalization: Energy and Politics in the Making of a new Turkey.” Energy Research & Social Science 41: 148–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2018.04.037.

- Fairhead, J., M. Leach, and I. Scoones. 2012. “Green Grabbing: A new Appropriation of Nature?” Journal of Peasant Studies 39 (2): 237–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2012.671770.

- Franco, J., L. Mehta, and G. J. Veldwisch. 2013. “The Global Politics of Water Grabbing.” Third World Quarterly 34 (9): 1651–1675. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2013.843852.

- Goodwin, J., and T. Skocpol. 1989. “Explaining Revolutions in the Contemporary Third World.” Politics & Society 17 (4): 489–509. https://doi.org/10.1177/003232928901700403.

- Gürel, B., B. Küçük, and S. Taş. 2019. “The Rural Roots of the Rise of the Justice and Development Party in Turkey.” Critical Agrarian Studies 46 (3): 457–479.

- Hall, R., I. Scoones, and D. Tsikata. 2015. Africa’s Land Rush: Rural Livelihoods & Agrarian Change (Vol. 42). Rochester, NY: Boydell & Brewer.

- Hann, C. M. 1990. Tea and the Domestication of the Turkish State (No. 1). Florida: Eothen Press.

- Hann, C., and I. Beller-Hann. 1998. “Markets, Morality and Modernity in North-East Turkey.” In Border Identities: Nation and State at International Frontiers, edited by T. M. Wilson, and H. Donnan, 237–262. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hardt, M., and A. Negri. 2009. Commonwealth. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Harris, L. M., and M. Işlar. 2014. “Neoliberalism, Nature, and Changing Modalities of Environmental Governance in Contemporary Turkey.” In Global Economic Crisis and the Politics of Diversity, edited by Y. Atasoy, 52–78. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Hill, A. 2017. “Blue Grabbing: Reviewing Marine Conservation in Redang Island Marine Park, Malaysia.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 79: 97–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.12.019.

- Hobsbawm, E. J. 1974. “Peasant Land Occupations.” Past and Present 62: 120–152. https://doi.org/10.1093/past/62.1.120.

- Hobsbawm, E., and T. Ranger. eds. 2012. The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Işlar, M. 2012. “Privatised Hydropower Development in Turkey: A Case of Water Grabbing?” Water Alternatives 5: 376–391.

- İnal, R., and C. Saraçoğlu. 2022. “The Making of Citizenship via tea Production: State-Sponsored Economic Growth, Nationalism and State in Turkey.” Nations and Nationalism 28 (4): 1444–1458. https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12858.

- Jacobs, R. 2018. “An Urban Proletariat with Peasant Characteristics: Land Occupations and Livestock Raising in South Africa.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 45 (5–6): 884–903. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2017.1312354.

- Kavak, S. 2021. “Rethinking the Political Economy of Rural Struggles in Turkey: Space, Structures, and Altered Agencies.” Journal of Agrarian Change 21 (2): 242–262. https://doi.org/10.1111/joac.12389.

- Kerkvliet, J. T. 1993. “Claiming the Land: Take-Overs by Villagers in the Philippines with Comparisons to Indonesia, Peru, Portugal, and Russia.” Journal of Peasant Studies 20 (3): 459–493. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066159308438518.

- Khagram, S. 2018. Dams and Development. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Knudsen, S. 2015. “Corporate Social Responsibility in Local Context: International Capital, Charitable Giving and the Politics of Education in Turkey.” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 15 (3): 369–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/14683857.2015.1091181.

- Kurtz, M. J. 2000. “Understanding Peasant Revolution: From Concept to Theory and Case.” Theory and Society 29 (1): 93–124. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007059213368.

- Kutlu, K. 2021. “The Need to Look Beyond the Right to Property: An Assessment of the Constitutional Court of Turkey’s Judgments on Urgent Expropriations for Hydropower Plants.” In Authoritarian Neoliberalism and Resistance in Turkey, edited by I. Borsuk, P. Dinç, S. Kavak, and P. Sayan, 129–150. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lefebvre, H. 1991. The Production of Space. 1st edition. New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Lindberg, S. 1994. “New Farmers’ Movements in India as Structural Response and Collective Identity Formation: The Cases of the Shetkari Sanghatana and the BKU.” Journal of Peasant Studies 21 (3–4): 95–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066159408438556.

- Linebaugh, P. 2014. Stop, Thief!: The Commons, Enclosures, and Resistance. Binghamton: PM Press.

- McAdam, D., S. Tarrow, and C. Tilly. 1996. “To map Contentious Politics.” Mobilization: An International Quarterly 1 (1): 17–34. https://doi.org/10.17813/maiq.1.1.y3p544u2j1l536u9.

- McMichael, P. 2012. “The Land Grab and Corporate Food Regime Restructuring.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 39 (3–4): 681–701. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2012.661369.

- Moore, B. 1967. Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Lord and Peasant in the Making of the Modern World. 1st edition. Boston: Beacon.

- Munro, J. M. 1974. “Migration in Turkey.” Economic Development and Cultural Change 22 (4): 634–653.

- Olivera, O., and T. Lewis. 2004. Cochabamba: water war in Bolivia. Boston: South End Press.

- Pahnke, A., R. Tarlau, and W. Wolford. 2015. “Understanding Rural Resistance: Contemporary Mobilization in the Brazilian Countryside.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 42 (6): 1069–1085. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2015.1046447.

- Paige, J. M. 1978. Agrarian Revolution. New York: The Free Press.

- Petras, J., and H. Veltmeyer. 2011. Social Movements in Latin America: Neoliberalism and Popular Resistance. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Petras, J., and H. Veltmeyer. 2018. “Class Struggle Back on the Agenda in Latin America.” Journal of Developing Societies 34 (1): 103–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/0169796X17753000.

- Petras, J. F., and H. Veltmeyer. 2019. “Neoliberalism and Social Movements in Latin America: Mobilizing the Resistance.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Social Movements, Revolution, and Social Transformation, edited by B. Berberoglu, 177–211. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Polletta, F., and J. M. Jasper. 2001. “Collective Identity and Social Movements.” Annual Review of Sociology 27: 283–305. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.283.

- Popkin, S. L. 1979. The Rational Peasant: The Political Economy of Rural Society in Vietnam. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Reardon, T., J. Berdegué, and G. Escobar. 2001. “Rural Nonfarm Employment and Incomes in Latin America: Overview and Policy Implications.” World Development 29 (3): 395–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(00)00112-1.

- Rocheleau, D. E. 2015. “Networked, Rooted and Territorial: Green Grabbing and Resistance in Chiapas.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 42 (3–4): 695–723. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2014.993622.

- Rulli, M. C., A. Saviori, and P. D’Odorico. 2013. “Global Land and Water Grabbing.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110 (3): 892–897. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1213163110.

- Scott, J. C. 1977. The Moral Economy of the Peasant:Rebellion and Subsistence in Southeast Asia . New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- Sevilla-Buitrago, A. 2015. “Capitalist Formations of Enclosure: Space and the Extinction of the Commons.” Antipode 47 (4): 999–1020. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12143.

- Skocpol, T. 1994. Social Revolutions in the Modern World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sobreiro, T. 2015. “Can Urban Migration Contribute to Rural Resistance? Indigenous Mobilization in the Middle Rio Negro, Amazonas, Brazil.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 42 (6): 1241–1261. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2014.993624.

- Soja, E. 1996. Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-and-Imagined Places. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Tugal, C. 2015. “Elusive Revolt: The Contradictory Rise of Middle-Class Politics.” Thesis Eleven 130 (1): 74–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/0725513615602183.

- Turkish Statistical Institute (TURKSTAT). 2012. Tarımsal Üretim Verileri. Retrieved 9 July, 2016, from http://tuikapp.tuik.gov.tr/bitkiselapp/bitkisel.zul.

- Turkish Statistical Institute (TURKSTAT). 2016. Nüfus Verileri. Retrieved 9 July 2016, from https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Kategori/GetKategori?p=Nufus-ve-Demografi-109.

- Van der Ploeg, J. D. 2018. The new Peasantries: Rural Development in Times of Globalization. New York: Routledge.

- Veltmeyer, H. 2019. “Resistance, Class Struggle and Social Movements in Latin America: Contemporary Dynamics.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 46 (6): 1264–1285. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2018.1493458.

- Wolf, E. 1969. Peasant Wars of the Twentieth Century. New York: Harper Torch Books.

- Wolford, W. 2004. “This Land is Ours now: Spatial Imaginaries and the Struggle for Land in Brazil.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 94 (2): 409–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.2004.09402015.x.

- Yavuz, Ş, and Ö Şendeniz. 2013. “HES direnişlerinde kadinlarin deneyimleri: findikli örneği.” Fe Dergi 5 (1): 42–58.