ABSTRACT

This article examines the discourse and practice of sustainable livestock intensification in Africa, using Tanzania as an analytic case. Drawing on archival and ethnographic research, I argue the growing interest in animal genetic improvement in the name of efficiency and sustainability mirrors earlier, incomplete colonial cattle crossbreeding experiments. These colonial efforts were justified by the need to improve yields while conserving the environment and ultimately facilitated state control over the bodies of indigenous peoples and animals. These historical legacies have profound implications for advancing climate justice in pastoral settings, where life depends on interspecies relations, knowledges, and practices of care.

‘Our lives depend on our fellow living beings. We live and die with our animals. Their survival depends on us, our survival depends on them. … But our leaders only seem to propose solutions that would make us both extinct’. – Author’s interview with a pastoralist in north-central Tanzania

Introduction

In recent years, the growing evidence of biophysical burdens of industrial livestock production has contributed to a narrative that livestock are ‘bad’ for the planet (Houzer and Scoones Citation2021; Köhler-Rollefson Citation2022). Of all livestock species, observers have singled out cattle as the largest polluter. Researchers at the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) suggest cattle are responsible for 65–77 percent of all livestock emissions globally (Gerber et al. Citation2013; Herrero et al. Citation2013), while Bill Gates, a major donor in African agriculture and livestock development, claims that ‘if [cattle] were a country, they would be the third-largest emitter of greenhouse gases!’ (Gates Citation2018). Patrick Brown, the CEO of Impossible Foods, went as far as to declare livestock ‘the most destructive technology on earth and almost entirely responsible for the global collapse of biodiversity’ (Nuttall Citation2021). In the Global North, concerns about the ecological ‘hoofprint’ of industrial livestock production (Weis Citation2013) – coupled with those about animal welfare, human labour conditions, and zoonotic health risks – have led to public calls to eliminate factory farming and move towards plant-based or plant-forward diets (Foer Citation2009; Taylor and Taylor Citation2020). Alongside activists and industry players, scientists have also been at the forefront of promoting dietary change as a climate change mitigation strategy (IPCC Citation2019; Citation2021; Poore and Nemecek Citation2018).

In the Global South, where millions of people depend on pastoralism as their primary livelihood and cultural way of life, an opposing dynamic is unfolding: a movement to increase livestock yields while minimising environmental impact, often branded as ‘sustainable livestock intensification’. In its 2006 landmark report, Livestock’s Long Shadow, the FAO highlighted that major transformations were necessary to curtail the negative environmental consequences of the livestock industry, but it nonetheless observed intensification was unavoidable in low and middle-income countries for the foreseeable future. Highlighting the growing demand for animal source foods and the so-called demise of subsistence production, the authors concluded: ‘There is a need to accept that the intensification and perhaps industrialisation of livestock production is the inevitable long-term outcome of the structural change process that is ongoing for most of the sector’ (Steinfeld et al. Citation2006, 283). Making intensification ‘environmentally acceptable’, they argued, would require ‘applying the right technology’ and ‘locating industrial livestock units in suitable rural environments’ (Steinfeld et al. Citation2006).

In Africa, the discussion on sustainable livestock intensification has likewise centred on promoting investments to increase the productivity, efficiency, and profitability of livestock production, while conserving the environment (Paul et al. Citation2020; Shikuku et al. Citation2017). These imperatives are centrally embedded in national ‘livestock master plans’ recently adopted in Tanzania, Ethiopia, and Rwanda and currently being considered in Kenya and the Gambia. Supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and ILRI, these master plans share a common goal of promoting ‘better [animal] genetics’ and associated improvements in feeds, veterinary services, and policy incentives for investors to boost production in ‘sustainable and climate-smart’ ways’ (ILRI Citation2015, 5; Citation2017, 1; Citation2018, xvi, xviii).Footnote1

In this article, I critically examine the emergent discourse and practice of sustainable livestock intensification in Africa, focusing specifically on the role of cattle genetic improvement and using Tanzania as an analytic case. Tanzania serves as a useful example for several reasons. According to the latest government figures, the country is home to one of the largest cattle populations in Africa with approximately 33.9 million cattle, 99.6 percent of which are raised in subsistence-oriented pastoral and agropastoral systems and 96.5 percent are classified as indigenous breeds (URT Citation2020). With large-scale commercial farms historically owning less than one percent of the national herd, state efforts to modernise the livestock sector in Tanzania, since colonial times, have always implied control over pastoralism (Hodgson Citation2001; Ndagala Citation1990; Parkipuny Citation1979; Sunseri Citation2013), defined broadly as a social and economic system founded on the interdependent relationship between mobile herders, animals, and variable ecosystems. Of all existing livestock master plans in the region, Tanzania’s is the most ambitious, with an estimated cost of USD 624 million. Investments in animal genetics, such as introducing ‘pure exotic breeds’, artificial insemination (AI), hormone synchronisation, and crossbreeding, comprise the single biggest budget item in the bovine meat and dairy sub-sector (ILRI Citation2018, 3). By historicising sustainable livestock intensification and livestock improvement in a long line of state interventions in veterinary science, animal husbandry, agro-pastoral commercialisation, and environmental management in Tanzania, I make the following set of arguments.

First, I argue that the rising interest in animal genetic improvement as a key component of sustainable livestock intensification echoes earlier colonial attempts at cattle crossbreeding as a prerequisite for livestock commercialisation. These colonial efforts were similarly justified by the need to increase yields, while reducing environmental degradation. A primary source of anxiety among scientists and state authorities during the colonial period was the so-called problem of overstocking: African ‘natives’ keeping too many ‘unproductive’ cattle per area of land that was believed to cause overgrazing and soil erosion. The idea that people should keep ‘fewer, bigger, and better’ cattle for commercial purposes and to improve resource use efficiency still prevails today, but it has been supplemented by the global neoliberal concern over the inefficiency of certain animal bodies: indigenous breeds belching too much relative to the amount of protein they yield that arguably increases greenhouse gas emission intensities of meat and milk. Despite the subtle shift in the narrative, the crossing of local female cattle with ‘grade stock’ or ‘proven bulls’ of foreign origin continues to feature prominently in national and global policy debates.

Second, and building on this, I contend that livestock and environmental improvement efforts in Tanzania, as in other parts of the colonial world, have historically been a bio-zoopolitical mechanism for expanding state control over the bodies and lives of indigenous peoples and animals. Historians have shown how the idea of breeds and the act of classifying and organising sexual difference within species through breeding have been central to maintaining a racial-colonial order, in which European domesticated animals were deemed more ‘modern’ and ‘civilised’ than the ‘primitive’ and ‘feral’ beasts of indigenous peoples (Aderinto Citation2022; Armstrong Citation2002; Mwatwara and Swart Citation2016). In Tanzania, diverse ethnic groups of livestock keepers have been blamed, time and time again, for possessing ‘backward’ knowledge of animal husbandry and environmental management. In turn, the animals they care for have been portrayed as genetically inferior and undesirable, lacking in productive capacity to generate revenue for the colonial state. These ideas informed research on crossbreeding as well as destocking campaigns to induce pastoralists to cull and sell their surplus ‘scrub’ animals, particularly female cattle dedicated to reproduction. What underlay these biosocial experiments were racist-speciesist assumptions that rationalised colonial oppression of African peoples and animals, as well as racist-sexist biases that naturalised the bodies of indigenous female animals as passive and superfluous and those of ‘pure exotic bulls’ as active and endowed with the primary creative force. As I will show, however, the results of these measures were inconclusive in Tanzania, because colonial scientists and administrators fundamentally misapprehended the cultural, ecological, and interspecies relationships on which pastoralism depends.

Third, I argue these historical legacies have profound implications for understanding and advancing climate justice in pastoral settings. Current policy discussions at the interface of livestock and climate change in the Global South are heavily skewed towards mitigation or achieving ‘low-emissions development’ through commercialisation and technological change (see also Crane, Bullock, and Gichuki Citation2020). Mitigation is not unimportant, but this narrow focus reflects what science studies scholars and political ecologists call ‘problem closure’: the defining of an environmental problem in a limited manner that prevents alternative ways of thinking about and acting upon the problem. As Forsyth (Citation2003) notes, problem closure has long been evident in mainstream policy debates on climate change, where the problem is often defined as too much greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, such that proposed solutions to climate change end up prioritising reducing emissions through technological fixes, rather than tackling its root causes and strengthening the adaptive capacities of communities disproportionately affected by its negative effects. The insistence on changing the genetic composition of indigenous breeds in places like Tanzania to become more productive and ‘climate smart’, as measured by the emission intensities of meat and milk, leaves little room for addressing other urgent eco-systemic issues. These include how historical legacies of land alienation, marginalisation, and ongoing capitalist enclosures of pastoral landscapes articulate with climate change-related extreme weather events to impair the mutual survival and reproduction of pastoralists, livestock, and the cultures and ecologies of which they are a part.

Fraser (Citation2021, 120 original emphasis) has recently argued that forging a transformative eco-societal transformation requires an ‘anti-capitalist and trans-environmental’ commonsense (see also Borras et al. Citation2021). This means moving beyond single-issue environmentalism that isolates climate change and interrogating the complex ways in which it is inextricably tied to the general crisis of capitalism: a system predicated on the chronic undervaluation of both nature and care work. As Fraser (Citation2021, 105) highlights, when capital destabilises ecosystems, ‘it jeopardises caregiving as well as the livelihoods and social relations that sustain it’. In the case of pastoralism, this work of daily provisioning and reproduction exceeds the human realm and entails cultivating care relations across species difference.

Bringing critical agrarian studies in dialogue with the burgeoning interdisciplinary field of critical animal studies, I suggest the fight for climate justice, especially in pastoral settings, must not only be anti-capitalist and trans-environmental but also anti-colonial and trans-species. As historian Saheed Aderinto (Citation2022, 3) writes, ‘we may not fully comprehend the extent of imperial domination until we bring animals into our understanding of colonialism’. Indeed, scholarship in animal geographies, multispecies studies, feminist science studies, and environmental history has revealed how colonial violence and the articulation of race, class, and gender have shaped and been shaped by the asymmetrical relations between humans and non-human animals (Deckha Citation2012; Gillespie and Collard Citation2015; Haraway Citation1989; Tsing et al. Citation2020; Wilcox and Rutherford Citation2018). In agrarian contexts, scholars have extended Foucault’s concept of biopower to farm animals to analyse how their bodies and reproductive lives are managed through an increasing array of biotechnologies to maximise productivity and profits, often under the guise of promoting efficiency and sustainability (Holloway et al. Citation2009; McGregor et al. Citation2021; Neo and Emel Citation2017; Twine Citation2010). Though agrarian studies and adjacent fields like political ecology have contributed important insights to the historical dynamics of pastoral livelihoods, dispossession, and herder-peasant conflicts (see e.g. Bassett Citation1988; Benjaminsen, Maganga, and Abdallah Citation2009; Walwa Citation2020), animals have often remained in the background. Where animals are foregrounded, including in the impressive array of pastoral studies Scoones (Citation2020) has surveyed, they (especially cattle) tend to be analysed through the lens of capital and production, rather than as an integral part of social, cultural, and ecological reproduction (for an exception, see Yurco Citation2022). In sum, attending to the relationship between animality, coloniality, and modernity and cultivating a trans-species perspective, I argue, are necessary to challenge the humanist assumptions ingrained in social theory, including agrarian political economy, and to illuminate new stakes and possibilities of studying rural life in the more-than-human Anthropocene (Galvin Citation2018).

My analysis proceeds as follows. In the first section, I critique two core assumptions undergirding sustainable livestock intensification, including the assumed inevitability of meatification and depastoralisation and the inefficiency of pastoralism. I, then, move on to contextualising these critiques in Tanzania. I historicise the evolution of government policies and attitudes towards pastoralism since the colonial era and illustrate how the state has mobilised animal breeding, destocking, and livestock commercialisation to transform the relationship between pastoralists, livestock, and the environment, but not without resistance. In the conclusion, I return to the broader implications of my arguments for rural climate justice and the future of pastoralism.

The arguments and evidence I present stem from research conducted between 2019 and 2022.Footnote2 Data collection involved document and discourse analysis of policy and scientific literature, archival research at the British National Archives (BNA), and ethnographic fieldwork in Tanzania. At the BNA, I consulted the Colonial Office records pertaining to the Department of Veterinary Science and Animal Husbandry, livestock and natural resource ordinances, cattle and meat industries, livestock diseases, and various agricultural schemes and development plans in cattle-rearing districts. Historical data were triangulated with findings from 26 interviews I conducted with Barabaig and Maasai pastoralists in Mbulu, Hanang, and Kiteto districts in Manyara Region in the semi-arid north-central highlands. I also draw on key themes from seven focus group discussions (four women-only, two men-only, one mixed gender groups) I facilitated in these districts with a total of 54 individuals, as well as unstructured interviews with ten Barabaig and Maasai activists.

Sustainable livestock intensification: questioning core assumptions

Inevitability of ‘the livestock revolution’ and depastoralisation?

Africa’s growing, and increasingly affluent, population’s demand for meat, milk, and eggs will double, triple, or even quadruple in the next few decades. The livestock sector will revolutionize in response to this growing demand. (FAO Citation2017, 4)

Another closely related assumption concerns the inevitability of depastoralisation / depeasantisation, or what Steinfeld et al. (Citation2006, 293) has described as the ‘likely and probably accelerating exit of smallholder livestock producers in developing countries as well as developed’. This assertion draws on a long-standing evolutionary theory in agricultural and development economics that posits a ‘natural transition from separate, extensive crop and animal production to integrated, more intensive forms’ (McIntire, Bourzat, and Pingali Citation1992, 12). As Scott (Citation2017) has argued, however, the presumption that sedentary agriculture is more ‘evolved’ form of food production than mobile forms of subsistence has been central to the founding of earliest agrarian societies and states; this view has also shaped the promotion of mixed crop-livestock farming as a more ‘rational’ form of land use than shifting cultivation and nomadic livestock keeping across colonial Africa (Sumberg Citation1998; Wolmer and Scoones Citation2000). Claiming the ‘demise of smallholders may not always be bad’ as it would mobilise labour required for industrial production, Steinfeld et al. (Citation2006, 283) ultimately concluded: ‘policies that attempt to stem the trend of structural change, in favour of small-scale or family farming, will be costly’ (Steinfeld et al. Citation2006).Footnote3

Though the nutrition transition and depastoralisation are broadly observable trends, the tendency to naturalise them is problematic on several grounds. First, there is no definitive historical evidence providing a causal link between economic wealth, urbanisation, and consumption of animal protein. The persistence of pastoralists, agropastoralists, fisherfolk, hunter gatherers, and other indigenous peoples around the world who might be income-poor but for whom herding, milking, fishing, hunting, and eating animal foods constitute a cultural way of life provide important evidence to the contrary. On the flip side, so do growing numbers of urban middle- and upper-class consumers who choose to be vegans and vegetarians for a variety of environmental, ethical, and personal-political reasons, as well as populations across the socioeconomic spectrum who eschew meat consumption on religious or spiritual grounds.

Over a century ago, Kautsky (Citation1988) in The Agrarian Question also presented a historical counterargument to the modernist explanation of nutrition transition. He argued that up until the fourteenth century, meat and dairy had constituted a routine part of ordinary peasant diets in Germany and other parts of Europe. Recent historical and archaeological evidence has corroborated this observation, demonstrating that meat, dairy, fish, fruits, and vegetables were all part of peasant diets in medieval England (Adamson Citation2004). The turning point was during the sixteenth century when the commoners were expelled from the lands, forests, and waters that had nourished and sustained them; with restricted access to pasture, peasants who owned livestock were forced to sell them to bring in cash to purchase food. As Kautsky writes (Citation1988, 30), the ‘peasant’s table was rapidly impoverished’ by these external forces, and eventually, ‘the peasant became a vegetarian’.

It is, therefore, ahistorical to solely rely on recent economic and demographic trends in income, price, income elasticity of demand, and population growth to project the future demand for animal source foods and prescribe generalised policy recommendations based on those incomplete estimates. The FAO’s Livestock’s Long Shadow had, in fact, acknowledged that the increase in demand for livestock products will ‘slow down and eventually reverse’ globally (Steinfeld et al. Citation2006, 229), but it fell short of considering the relevance and ramifications of the recommendation for continued intensification. As Berson (Citation2019, 294) aptly put it, ‘growing demand for meat is not simply an outcome of growing affluence. It is a symptom of the inequality and oppression that have accompanied that affluence’ (see also Weis Citation2013).

Inefficiency of pastoralism, pastoralists, and traditional breeds?

The major mitigation potential lies in ruminant systems operating at low productivity, for example in Latin America and the Caribbean, South Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa … [this] potential can be achieved through better animal and herd efficiency. (Gerber et al. Citation2013, 44)

But how useful or appropriate is the metric of emission intensity? First, there remain significant gaps and uncertainties in the data used to calculate emission intensities of livestock commodities (Houzer and Scoones Citation2021). Various scientists have problematised how existing data are derived from studies of intensive livestock systems in temperate regions, and then extrapolated to extensive systems elsewhere around the globe (Ericksen, Thornton, and Nelson Citation2020; Manzano and White Citation2019; Rufino et al. Citation2014). As Ericksen, Thornton, and Nelson (Citation2020, 625) observe, ‘without more accurate data, existing models used to calculate emissions from smallholdings are more likely to give unreliable estimates, and, in turn, are less useful for policy in the tropics’. By abstracting different production systems from their local contexts and rendering them commensurable to allow for comparison, the metric of emission intensity simplifies the complexity of how animals are raised in different parts of the world. Manzano and White (Citation2019, 94), thus, demand that calls to intensify livestock production as a ‘climate-friendly’ strategy ‘should be halted until there are sufficient data with which to inform a complete assessment’.

Second, defining emission intensity in terms of emissions per unit of animal product – rather than per unit of land – presupposes a priori desirability of industrial production: the higher the yields, the lower the emission intensity (McGregor et al. Citation2021). This biased definition opens doors for powerful actors to shift the conversation and burdens of climate change mitigation from intensive livestock operations dominant in the Global North – which some ambiguously characterise as ‘landless’ systems (see Seré and Steinfeld Citation1995) – to the extensive pastoral systems in the Global South. Moreover, the narrow definition has the effect of blaming environmental degradation on pastoralists and subsistence producers – an all-too-familiar narrative political ecologists have long critiqued (Davis Citation2007; Leach and Mearns Citation1996) – as well as their companion species.

As I will return to later, reducing human-animal-environment relations into a metric like emission intensity that values productivity above all else flattens the richness of interspecies interactions on which pastoralism depends. In northern Kenya, Davis (Citation2001, 148) has described cattle as ‘the fulcrum of life’ for Ariaal pastoralists. When herders meet, they ‘ask first of the well-being of the herds, then of the families. Each animal has a mark and a name, a personality setting it apart’ (p. 148). In Sahelian West Africa, Krätli (Citation2008) and Turner (Citation2009) have also shown how herders use a rich collection of vocabulary to describe the colours, patterns, and individuality of animals; this plays an important role in both identifying animals and cultivating social bonds across generations, as animals and their offspring tied to the memory of their caretaker are often presented as gifts. Similar practices were observed among the Barabaig and Maasai pastoralists I interviewed in Tanzania, and as Köhler-Rollefson (Citation2022, 2) reminds us, there are many others examples of ‘animal-oriented cultures’ worldwide where people relate to and care for livestock as members of their kin.

The narrative that pastoralists lack proper knowledge of animal and environmental care glosses over the fact that they are, ‘first and foremost, ecologists’, as one Maasai activist told me, a sentiment which other activists shared.Footnote4 For generations, they have experimented with and adopted different forms of strategic mobility to respond to variability and uncertainty in forage and environmental conditions (Behnke, Scoones, and Kervan Citation1993; Homewood and Rodgers Citation1991; Krätli et al. Citation2013). Likewise, the narrative that livestock in extensive transhumance systems are unproductive and inefficient ignores the important ecological role they play, especially in the drylands. Compared to large-scale commercial operations that cannot function without fossil fuels, traditional low-input livestock systems are energetically efficient: they have little to no other energy needs other than those provided by the sun. Grazing livestock convert solar energy absorbed by human-inedible biomass into milk, butter, ghee, meat, fibre, and other diverse animal products (Köhler-Rollefson Citation2022). Through seasonal migration and grazing, animals raised by pastoralists help stimulate grass roots development, which, in turn, helps store carbon in the soil, retain and filter groundwater, prevent fires and floods, and maintain critical habitat for wildlife in the grasslands (Herrera Citation2020; Köhler-Rollefson Citation2022). As they move from one pasture to another, livestock return nutrients to the soil through manure and urine; they also transport and disperse seeds and fruits, an essential service that fosters community species richness (Manzano and Malo Citation2006).

Despite these cultural and ecological complexities, pastoralism has long been simplified and misunderstood in Tanzania. National agricultural and livestock policy documents have repeatedly identified the ‘low genetic potential’ of indigenous breeds and the nomadic systems under which they are raised as major obstacles to development (URT Citation1997, 49; Citation2006, 22; Citation2015, 7). The current livestock policy further describes pastoralism as a system that rests on ‘uncontrolled mobility’ and is ‘constrained by poor animal husbandry practices, lack of modernisation, accumulation of stock beyond the carrying capacity, and lack of market orientation’ (URT Citation2006, 1). These assumptions have long legitimated the displacement and sedentarisation of pastoralists for the creation of commercial ranches, conservation areas, agricultural schemes, private hunting concessions, among other modernist projects (see e.g. Gardner Citation2016; Homewood and Rodgers Citation1991; Lane Citation1994). As I will show next, the negative stereotypes of pastoralism, pastoralists, and traditional animals and the consequent state efforts to modernise them are not new but have deep roots in colonial history. This is a history marked by decades of frustrating development experiments and the resistance of pastoral peoples and animals.

The coloniality of livestock modernisation in Tanzania

Tanzania was among the first African colonies in which Europeans entertained the idea of cattle crossbreeding. In the wake of the rinderpest epizootic of the 1890s which decimated indigenous livestock and wildlife, the governor of German East Africa proposed introducing foreign cattle breeds to rebuild the colony’s herd. Colonial authorities believed the cattle that survived the epidemic were too small, disease-prone, and only minimally productive of meat and milk to contribute value to the colonial economy (Sunseri Citation2015). Between 1898 and 1899, German East Africa imported over 15,000 breeding bulls and cows from Germany, India, and Zanzibar; and in 1905, the government established Tanzania’s first Livestock Research Station in Mpwapwa, Dodoma in the central semi-arid zone to facilitate research on disease control and breed improvement. However, research progress was slow. Policymakers in the metropole were reluctant to invest in veterinary science and infrastructure in German East Africa, due in part to the relative absence of white settlers there vis-à-vis German Southwest Africa (Namibia), where zoonotic diseases were believed to pose a more urgent threat to the European settler ranching economy than to African pastoralism (Sunseri Citation2015).

When Britain took control over the territory under the League of Nations mandate following Germany’s defeat in World War I, livestock improvement and commercialisation gained momentum. The promotion of meat industry in colonial Tanzania was closely tied to the need to improve the diets of ‘under-nourished natives’ and to reduce ‘wastage labour’ at plantations and mines that were key to maintaining Britain’s hegemony.Footnote5 Colonial administrators also hoped to increase meat production in Tanzania and other colonies to help relieve the perceived global meat shortage during and after World War II (Sunseri Citation2013).

Upon establishing the Department of Veterinary Science and Animal Husbandry (DVSAH) in 1921, the colonial government imported breeding bulls from England, Scotland, South Africa, and India (Wilson Citation2018). Housed at the Government Stock Farm in Dar es Salaam, the plan was to observe how these ‘imported sires’ would react to the local environment and have them mount the females of the supposedly inferior indigenous breed: the Tanganyika/Tanzania Shorthorn Zebu. This local Zebu, which has been and still is the most common breed in Tanzania, comes in many colours and is distinguished by their short horns and musculo-fatty thoracic humps that vary in shape and size ( and ). The breed traces its origin to southern Asia and is believed to have been introduced in large numbers by Arab and Indian traders during the Arab invasion of the East African coast around the seventh century (Mwai et al. Citation2015). Since then, diverse livestock-keeping communities have selected them for specific traits, ranging from colours to adaptability to heterogeneous environments. The breed today comprises multiple strains, including Iringa Red, Singida White, Mkalama Dun, Mbulu, Maasai, Gogo, Chaga, and Sukuma, whose names derive from their places of origin and ethnic groups who have historically conserved them (URT Citation2019).

Figure 1. A herd of Tanzania Shorthorn Zebu en route to a watering hole during the dry season in central Tanzania. Photo by author.

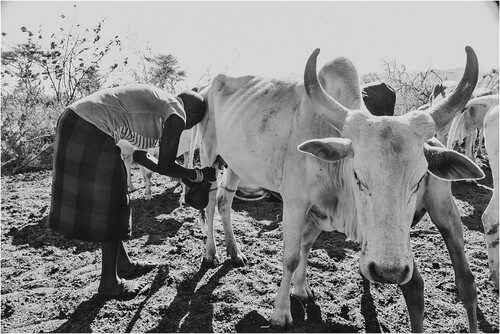

Figure 2. A Barabaig pastoralist woman milking a Zebu cow in the early morning hours during the dry season in north-central Tanzania. Photo by author.

Throughout the 1920s, the colonial government issued several ‘grade bulls’ to Chiefs and local Native Authorities to ascertain ‘their ability or otherwise to stand up to African conditions’.Footnote6 However, tracking their progress proved challenging. As F. J. McCall, the first Director appointed to DVSAH in Tanganyika Territory observed in 1927, ‘it is exceedingly unlikely that anyone initiating the process will live to see much accomplished in the way of tangible progress’.Footnote7 Nonetheless, he observed that ‘under European supervision and in more temperate well watered areas’ and in the hands of non-African settlers, ‘the introduction of European blood into Zebu herds is feasible and profitable’.Footnote8

In the 1930s, concerned that ‘little or nothing had been done by Europeans to improve indigenous stock’, colonial veterinary and agricultural officials conducted a survey of Africa’s ‘native cattle’ to better assess their phenotypic characteristics and their potential for genetic improvement and commercialisation (Curson and Thornton Citation1936, 617). Published in 1936, the survey results compared different cattle breeds from across Africa, including Tanganyika Territory, for their conformation, colouration, average live and carcass weight, growth rate, reproductive rate, and lactation yield, among others. Special attention was paid to whether the cattle were straight-backed or humped and whether they were polled or horned, arguably with the assumption that genetic traits European breeds exhibited were superior or at least the benchmarks upon which African animals would be measured (Curson and Thornton Citation1936; Darling Citation1934). The practice of scientific stock breeding was deeply intertwined with the production of racial knowledge across species lines. As Mwatwara and Swart (Citation2016) have shown in Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), colonial authorities often extended racialised identities onto African cattle. If the ‘natives’ were found to possess what colonialists judged to be decent breeds, they argued those animals must have originated in Europe or intermingled with ‘good’ blood of European cattle from Bechuanaland Protectorate (Botswana) (Mwatwara and Swart Citation2016, 341).

In his response to the survey on ‘Africa’s native cattle’, H. E. Hornby, a veterinary pathologist who succeeded McCall as Director of DVSAH of Tanganyika Territory in 1930, described the indigenous Zebu as neither a good beef type nor a good dairy type as ‘judged by European standards’ (Hornby 1930 cited in Curson and Thornton Citation1936, 649). Elsewhere, however, he had described them as a ‘hardy’ breed that could survive in places ‘where a European ox would starve and die’.Footnote9 McCall had made similar observations during his tenure. He commended local Zebu’s ‘ability to stand up to the long, hard months of the dry season’, but when speaking of their productive value, he reduced them to ‘indifferent milkers’ whose owners had paid ‘more attention … to the size of their humps than to the shape of their rumps’ (McCall 1928 cited in Epstein Citation1955, 91). He surmised ‘the native [must be] a lazy, ignorant fellow’ to be keeping such ‘small oxen without ribs, yet, burdened by a hump’ – a kind of animal ‘no intelligent European could possibly be content to raise’.Footnote10 This anxiety about ‘the problem of the hump’, whose function and evolutionary significance was unknown, led some colonial authorities to believe that continued crossbreeding would somehow ‘clear up’ this unwanted trait (Mumford 1930 cited in Curson and Thornton Citation1936, 689).

Regarding breeds as manifestation of certain genes that are either superior or inferior based on their contribution to yields, colonial veterinary scientists and officials failed to understand the way African pastoralists valued their cattle and their unique traits like the hump. According to Barabaig pastoralists I interviewed, the hump, which comprises largely of fat and muscle tissue, is what makes traditional breeds more resilient to droughts than exotic breeds; they are able to mobilise reserved energy stored in the hump to adapt to harsh environments, especially when they have to trek long distances in search of pasture and water during prolonged dry seasons (see also Rout and Behera Citation2021). The benefits of the hump go beyond the ecological. When a woman gives birth, cattle is slaughtered to help nourish the mother through recovery; the hump is an important beef cut that is shared with neighbours to celebrate the child’s arrival into the community.Footnote11 Barabaig women also described how they boil the hump fat and use the solidified product as lubricant, emollient, and cooking ingredient, like when making soft ugali [maize porridge] for the sick.Footnote12 Maasai women likewise attested to using the hump fat for cooking vegetables and for decorating their bodies by mixing the melted oil with soil.Footnote13

A decade into experimentation, the effects of crossbreeding on livestock production and productivity were negligible. McCall reported in 1929 that the progeny resulting from crossing indigenous Zebu cows with ‘really good’ exotic bulls ‘were on the whole inferior’ to their parents (McCall 1929, 71 cited in French Citation1940, 13). Hornby reported similar outcomes in 1933. He noted that the first-generation crossbreeds proved to be ‘extraordinarily intractable’, prompting the government to rethink the value of the ‘greater docility of the average Tanganyika Zebu’ (Hornby 1933 cited in Curson and Thornton Citation1936, 680). In an article in Empire Journal of Experimental Agriculture in 1940, M. H. French, a biochemist at the Mpwapwa Livestock Research Station outlined numerous ‘degenerative symptoms’ resulting from crossbreeding experiments (French Citation1940, 15). He stated the ‘grading up’ of select indigenous Zebu cows with purebred European bulls, such as the Friesian and Ayrshire, resulted in ‘constitutional failure[s]’, where the offspring became ‘leggy … tucked-up with poorly spring ribs, scraggy necks, diminished heart-girth, and depth of chest’ (French Citation1940, 14–15). Comparing similar results from India, Jamaica, the Philippines, and Brazil, French (Citation1940, 16) concluded ‘grade calves which contain too high an admixture of European blood in their ancestry develop into inferior types’. Rather than promoting crossbreeding, he recommended encouraging ‘the native to manage grazing better … to limit stock numbers to the carrying capacity of the land, and to make him [sic] realize that one good milking-cow is better than several poor ones’ (French Citation1940, 12).

By defining overstocking as a ‘menace’, ‘a growing evil’, and ‘the most serious of all erosion problems’, colonial scientists and officials came to believe that destocking was what was ‘necessary to save the African from self-destruction’.Footnote14 From the 1930s onwards, crossbreeding efforts went hand in glove with destocking campaigns. Destocking, in essence, was a form of population control that targeted both human and nonhuman animals. In the name of development and environmental improvement, colonial authorities forced African livestock keepers to castrate and sell ‘unsuitable animals’, and cull their oldest, weakest, and ‘undesirable breeding stock’.Footnote15 In Mbulu district, the colonial government also forced the resettlement of thousands of livestock keepers to reduce the perceived problems of overpopulation and land degradation.Footnote16 To facilitate the absorption and marketing of destocked cattle, the colonial government set up designated auction markets, built public abattoirs, and partnered with white settler-backed private firms to establish meat extract/corned beef factories in areas where overstocking was considered rampant.Footnote17 These destocking measures were particularly important during the depression years of the 1930s, when the colonial veterinary service was starved of personnel, funds, and equipment to carry on with the breeding work.Footnote18 What began as a voluntary scheme, destocking became compulsory by the end of the 1940s.Footnote19

Despite these sustained government efforts, the results of destocking were inconclusive in Tanzania, as in other parts of colonial Africa where similar schemes were tested (Mwatwara and Swart Citation2016; Raikes Citation1981). This was because African livestock keepers refused to sell their cattle, especially at below market prices; if they sold, they were more inclined do so to private buyers who offered more competitive prices than what the government did. Pastoralists resisted parting with female cattle, which facilitated restocking rather than destocking, fundamentally foiling government plans. Administrators blamed much of the overstocking to ‘the unproductive female being kept to give yet one more calf’ and recommended more active interventions in ‘the culling of females’ than the castration of steers.Footnote20 Again, colonial authorities failed to appreciate why the African ‘natives’ would hold onto their presumed inferior beasts, especially females, just as they had misunderstood the multiple uses and values of the hump discussed earlier.

As the vast literature on East African pastoralism demonstrates and as my interviews further show, cattle, first and foremost, signifies wealth, security, and insurance; cattle are, in effect, ‘live stock’ or living assets. Pastoralists tend to sell cattle only when there is an economic need, such as buying grains and necessities and paying medical bills, school fees, and for other emergencies. Similarly, they slaughter sparingly on special occasions and for cultural rituals and celebrations.Footnote21 A Barabaig male elder I interviewed best summarised pastoralists’ reluctance to selling cattle: ‘Cattle is our bank. Imagine someone comes to you and forces you to reduce your savings. Would you do it?’Footnote22

Pastoralists’ tendency to hold on to female cattle – what scientists and policymakers still problematise today as ‘breeding overhead’ – has to do with the fact that cows are foundational to social and cultural reproduction. They provide the mainstay of pastoralist diets (i.e. milk and milk derivatives like butter and ghee), and the reproduction of the herd over time ensures the continuation of cultural traditions, such as the gifting of cattle at major life events, including birth, a child’s first teething, circumcision, and marriage. This is why most pastoralist herds predominantly consist of females and their offspring. When it comes to reproduction, the choice of bulls is not unimportant, but many pastoralists make breeding decisions based on maternal lineages, often naming new-born calves after their mothers to maintain the matriarchal herd structure (Galaty Citation1989; Köhler-Rollefson Citation2022; Krätli Citation2008). In short, the productivist and patriarchal lens through which colonial officials valued cattle was incommensurate with how animals were deeply embedded in the social and cultural lives of pastoralists and vice versa.

After repeated unsuccessful attempts to improve and control ‘native’ cattle, the colonial government modified its breeding plan between the 1940s and 1950s. The new strategy entailed crossbreeding the local Zebu with different strains of Zebu from Pakistan and India, namely the Red Sindhi and Sahiwal. The aim was to produce a dual-purpose (meat and dairy) cattle that were both high-yielding and better suited to Tanzania’s semi-arid climates. The experiment eventually resulted in the creation of a new synthetic breed, called the Mpwapwa, named after the research station where it was developed. At the time of the breed’s declaration in 1958, its genetic makeup comprised roughly 55 percent Asian (35 percent Red Sindhi, 20 percent Sahiwal), 35 percent African (20 percent Tanzania Shorthorn Zebu, 10 percent Boran, 5 percent Ankole), and 10 percent mixed European breeds (Getz et al. Citation1986).

Postcolonial reverberations

Breed improvement efforts continued after Tanzania gained independence in 1961 as the Mpwapwa never reached its projected productivity targets. Whereas prior experiments had relied on natural mating, AI – an assisted reproductive technology developed in the early twentieth century which now constitutes the centrepiece of industrial livestock systems (Clarke Citation1998) – became available at research stations in Tanzania in the late 1960s. Notwithstanding the less than ideal results from previous decades, scientists believed ‘the easiest remedy’ to improve Mpwapwa productivity, particularly the ‘milk let-down’ was ‘to increase the proportion of taurus [European] inheritance’ in its blood (Syrstad Citation1990, 21).

Most experimental crossbreds were kept at livestock research stations, but in the early 1970s, some 90 Mpwapwa bulls were distributed in USAID-funded ranching associations in Maasailand to boost beef production for domestic and international markets (Hayuma Citation1991). As Moringe ole Parkipuny, the late Maasai activist and a former member of parliament wrote in 1979, this intervention was ill-conceived and fraught with adverse consequences. He criticised how the ‘learned, Yankee livestock experts’ haphazardly ‘dumped [the alien animals] in a new habitat’, only to have them perish prematurely: the so-called improved bulls ‘succumbed to long trekking for grass and water … required more food and water … and were particularly susceptible to East Coast Fever and other diseases’ (Parkipuny Citation1979, 150). A terminal independent project evaluation described these results as something that ‘could have been predicted at the outset’ (Sorenson et al. Citation1979, 71).

In one village in Kiteto District where one USAID ranching association (Tamalai) was established, elders I interviewed recalled how American managers brought in around 50 of these improved bulls in the hopes of upgrading the local Zebu. More than 40 years later, they said ‘no trace’ of those animals could be found in the village, because most of those animals died and people went back to their inherited ways of livestock raising.Footnote23 Elders further noted how the large size of imported bulls harmed the small local heifers and cows during mounting, which made them regret contributing their animals to the ranching association to begin with.Footnote24 Rather than seeing the project failure as symptoms of broader social, economic, and political problems, development planners blamed the Maasai for their unwillingness to change their traditional ways and participate effectively in ranch maintenance (Hodgson Citation2001; Homewood and Rodgers Citation1991).

In sum, the regulation of bodies and lives of indigenous pastoralists and animals was central to the intertwined colonial desires and anxieties about civilising the ‘natives’, disease control, environmental conservation, food (meat) security, and capital accumulation. Tanzania was quintessentially a ‘living laboratory’ (Tilley Citation2012), in which human and non-human animals simultaneously became objects of colonial biosocial experiments. Rosenberg (Citation2016, 70) has described colonial animal production as a ‘laboratory for multispecies biopolitical orchestration’, but a laboratory in which the speculative nature of experiments always presents the possibility of failure. He was writing about hog breeding and commercialisation in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century settler colonial US, but his observation resonates with the case I presented here. Although contemporary development policies and programmes on livestock improvement and intensification are clothed in new language of sustainability, efficiency, and climate-smartness, their colonial imprints are unmistakably clear.

Conclusion

The pastoralists I met with in the drylands of north-central Tanzania were not opposed to crossbreeding or adopting new technologies. They simply wished to do so on their own terms and when the conditions were right. They acknowledged that ‘improved’ breeds generally put on weight faster, generated more milk and meat, and could be sold at higher prices even during the dry season when livestock prices tend to be lower. But they also knew these animals required more feed, water, minerals, supplements, veterinary drugs, labour time, and other resources to maintain their health and well-being. At a time when droughts are becoming more frequent and intense and when access to grazing land is diminishing by the day due to large-scale and everyday land encroachments by the state, private actors, and fellow crop cultivators, introducing exotic or crossbred animals was the last thing on their minds. They were more interested in introducing smaller ruminants such as goat and sheep that have lower feeding and watering requirements, selecting for animals within their herds who exhibit greater drought and disease tolerance, and migrating seasonally to areas with better grass and water access during extended dry periods.Footnote25 These flexible herding and breeding decisions are based on traditional knowledges and sensibilities that have enabled pastoralists to sustain their livelihoods over centuries—decisions that are based on ethics of care, contradistinctive from the logics of control and domination that underlay colonial and postcolonial projects of livestock and environmental improvement (Nori and Scoones Citation2019; Scoones Citation2023).

In 2022/23, the livestock sector in Tanzania will receive a mere 0.2 percent of the national budget, most of which will go towards investing in large-scale ranches, feed production, and processing factories, and expanding AI services to provide livestock keepers with ‘quality breeds’ (Shekighenda Citation2022). Except for building and renovating four cattle troughs in areas affected by drought, no public investment is currently allocated for supporting pastoralism, including ensuring seasonal mobility of humans and animals, providing extension services to confront emerging climate-related challenges, and stewarding breed and biological diversity.

The FAO (Citation2015) estimates the proportion of the world’s livestock breeds that are at risk of extinction has increased from 15 to 17 percent between 2005 and 2014, due to such factors as crossbreeding, climate change, disease epidemics, and inadequate institutional frameworks on livestock biodiversity. In the US, only five companies provided 90 percent of all bull semen in the early 2000s (Neo and Emel Citation2017); one of them, World Wide Sires, has partnered with American organisations like the USAID, Gates Foundation, and Land O’Lakes’s to improve AI services in Tanzania to maximise dairy output (see Land O’Lakes Citation2007). Köhler-Rollefson (Citation2021, 62) argues, ‘the need for livestock to be optimally adapted to their respective environments means that breeding must remain in the hands of local livestock keepers and cannot be outsourced to global genetics companies that provide one type-fits-all options’. I could not agree more. Extensive livestock systems may be perceived as unproductive or inefficient not because pastoralists have poor knowledge or animals possess bad genes, but precisely because of the compounding effects of historical dispossessions, discrimination, and the increased unpredictability and intensity of precipitation due to climate change, which rich nations have largely caused.

As a pastoralist intimated in the epigraph of this article, climate change affects the mutual survival and regenerative capacity of all beings on Earth. Critical agrarian scholars ought to be able to account more fully for the interspecies relationings between humans and non-humans in rural areas and challenge the systems of power that impair their collective thriving. There is an urgent need to advance decolonial and multispecies ways of thinking, knowing, and doing that foreground the knowledges, needs, and aspirations of those on the frontlines of climate change and to question the solutions that once served as weapons of colonial domination. Future research in agrarian studies would, thus, benefit from conversations with not only the extensive literature on pastoralism, which Scoones (Citation2020) has importantly highlighted, but also fields as diverse as animal and more-than-human geographies, environmental history, and feminist science and technology studies, from which this article has drawn inspiration.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge Amelia Balik, Mwangi Chege, Jessica Craigg, Gidufana Gafufen, and Lembulung M. Ole Kosyando for their assistance at various stages of the research. I am grateful to the staff at the British National Archives at Kew for help in accessing historical sources and the pastoralist women and men who graciously welcomed me into their bomas in Manyara. My thanks to Ross Doll, Ryan Nehring, Nancy Lee Peluso, Meg Mills-Novoa, and Sunaura Taylor for their kind feedback on earlier ideas and versions of this paper. I also thank Jun Borras, Shaila Seshia Gavin, and Ruth Hall for their editorial guidance and the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Youjin B. Chung

Youjin B. Chung is a sociologist and geographer who studies the relationship between gender, intersectionality, rural development, and environmental change in East Africa, particularly Tanzania. Her work spans the political economy of development, feminist political ecology, critical agrarian studies, science and technology studies, critical animal studies, and African studies. She is an assistant professor in the Energy and Resources Group and the Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management at the University of California, Berkeley.

Notes

1 These policy incentives include those that would ease the bureaucratic burden of establishing commercial ranches, feedlots, and processing plants, as well as tax breaks and subsidized leasing rates to private investors (ILRI Citation2015; Citation2017; Citation2018). These policy measures have the danger of facilitating what Schneider (Citation2014) has called ‘meat grabbing’, the acquisition of land for industrial livestock and feed production.

2 This research has been approved by the Committee for Protection of Human Subjects at the University of California, Berkeley (Protocol Number: 2020-09-13670)

3 For a more critical historical analysis of depastoralisation, see Caravani (Citation2019).

4 Interview KI.8, August 2022; Interview KI.6, August 2022; Interview KI.3, July 2022.

5 BNA/CO 691/152/5, The Tribes of Tanganyika: Their Districts, Usual Dietary and Pursuits by R. C. Jerrard, Assistant District Officer in Charge of Labour, 1936, 1.

6 British National Archives (BNA)/CO 691/99/17, Veterinary Department Annual Report, 1927, 78.

7 British National Archives (BNA)/CO 691/99/17, Veterinary Department Annual Report, 1927, 78.

8 British National Archives (BNA)/CO 691/99/17, Veterinary Department Annual Report, 1927, 78.

9 BNA/CO 691/139/5, A Memorandum of the Economics of the Cattle Industry in Tanganyika by the Department of Veterinary Science and Animal Husbandry, 1934, 17.

10 BNA/CO 691/99/17, Veterinary Department Annual Report, 1927, 92.

11 Focus group discussions No. 1–7, August-September 2022.

12 Focus group discussion No. 2–3, August 2022.

13 Focus group discussion No. 6–7, August-September 2022.

14 BNA/CO 892/11/1, Veterinary Department Annual Report, 1951, 31; BNA/CO 691/193, East and Central African Meat and Feeding Stuffs Survey, 1949, 3; BNA/CO 691/139/5, A Memorandum of the Economics of the Cattle Industry in Tanganyika by the Department of Veterinary Science and Animal Husbandry, 1934, 19.

15 BNA/CO 691/99/17, Veterinary Department Annual Report, 1927, 77; BNA/CO 892/11/1, Synoptic Review of the Veterinary Department Annual Report 1951, 15.

16 BNA/CO 892/11/1, Synoptic Review of the Report of the Development of Mbulu District 1951.

17 BNA/CO 691/96/15, Meat Industry, 1928; BNA/CO 691/111/1, Meat Industry, Meat Rations Ltd., 1930.

18 BNA/ CO 691/183, Veterinary Department Annual Report, 1941, 1; BNA/ CO 691/183, Veterinary Department Annual Report, 1942, 2; BNA/CO 892/11/1, Synoptic Review of the Veterinary Department Annual Report 1951, 8.

19 BNA/CO 892/11/1, Veterinary Department Annual Report, 1951.

20 BNA/CO 892/11/1, Veterinary Department Annual Report, 1951, 13.

21 Focus group discussions, No. 1-7, August-September 2022.

22 Interview HH.4, August 2022.

23 Focus group discussion No. 6, August 2022.

24 Focus group discussion No. 6, August 2022.

25 Focus group discussions No. 1–7, August-September 2022.

References

- Adamson, M. W. 2004. Food in Medieval Times. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

- Aderinto, S. 2022. Animality and Colonial Subjecthood in Africa: The Human and Nonhuman Creatures of Nigeria. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press.

- Armstrong, P. 2002. “The Postcolonial Animal.” Society & Animals 10 (4): 413–419. https://doi.org/10.1163/156853002320936890

- Bassett, T. J. 1988. “The Political Ecology of Peasant-Herder Conflicts in the Northern Ivory Coast.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 78 (3): 453–472. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.1988.tb00218.x

- Behnke, R., I. Scoones, and C. Kervan, eds. 1993. Range Ecology at Disequilibrium: New Models of Natural Variability and Pastoral Adaptation in African Savannas. London: Overseas Development Institute.

- Benjaminsen, T. A., F. Maganga, and J. Abdallah. 2009. “The Kilosa Killings: Political Ecology of a Farmer–Herder Conflict in Tanzania.” Development and Change 40 (3): 423–445. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2009.01558.x

- Berson, J. 2019. The Meat Question: Animals, Humans, and the Deep History of Food. Boston: MIT Press.

- Borras Jr., S. M., I. Scoones, A. Baviskar, M. Edelman, N. L. Peluso, and W. Wolford. 2021. “Climate Change and Agrarian Struggles: An Invitation to Contribute to a JPS Forum.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 49 (1): 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2021.1956473

- Caravani, M. 2019. “‘De-Pastoralisation’ in Uganda’s Northeast: From Livelihoods Diversification to Social Differentiation.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 46 (7): 1323–1346. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2018.1517118

- Clarke, A. E. 1998. Disciplining Reproduction: Modernity, American Life Sciences, and ‘the Problems of Sex’. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Crane, T. A., R. Bullock, and L. Gichuki. 2020. Social Equity Implications of Agricultural Intensification and Commercialization, with a Focus on East African Dairy Systems Implications for Low-Emissions Development. Wageningen: CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security, Working Paper No. No. 327.

- Curson, H., and R. W. Thornton. 1936. “Contribution to the Study of African Native Cattle.” Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Science and Animal Industry 7 (2): 613–739.

- Darling, F. F. 1934. Imperial Bureau of Animal Genetics. Animal Breeding in the British Empire: A Survey of Research and Experiment. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd.

- Davis, W. 2001. Light at the Edge of the World: A Journey Through the Realm of Vanishing Cultures. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre.

- Davis, D. K. 2007. Resurrecting the Granary of Rome: Environmental History and French Colonial Expansion in North Africa. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press.

- Deckha, M. 2012. “Toward a Postcolonial, Posthumanist Feminist Theory: Centralizing Race and Culture in Feminist Work on Nonhuman Animals.” Hypatia 27 (3): 527–545. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.2012.01290.x

- Delgado, C., M. Rosegrant, H. Steinfeld, S. Ehui, and C. Courbois. 1999. Livestock to 2020: The Next Food Revolution. Washington, DC, Rome, Nairobi: IFPRI, FAO, ILRI.

- Epstein, H. 1955. “The Zebu Cattle of East Africa.” The East African Agricultural Journal 21 (2): 83–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/03670074.1955.11665014

- Ericksen, P., P. K. Thornton, and G. C. Nelson. 2020. “Ruminant Livestock and Climate Change in the Tropics.” In The Impact of Research at the International Livestock Research Institute, edited by J. McIntire, and D. Grace, 601–638. Wallingford: CABI.

- FAO. 2015. The Second Report on the State of the World’s Animal Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. Rome: FAO.

- FAO. 2017. Thinking Beyond Livestock Today for the People of Tomorrow. Africa Sustainable Livestock 2050. Rome: FAO.

- Foer, J. S. 2009. Eating Animals. New York: Little, Brown, and Company.

- Forsyth, T. 2003. Critical Political Ecology: The Politics of Environmental Science. London: Routledge.

- Fraser, N. 2021. “Climates of Capital: For a Trans-Environmental Eco-Socialism.” New Left Review 127 (Jan/Feb): 34.

- French, M. H. 1940. “Cattle-Breeding in Tanganyika Territory and Some Developmental Problems Relating Thereto.” The Empire Journal of Experimental Agriculture 8 (29): 11–22.

- Galaty, J. G. 1989. “Cattle and Cognition: Aspects of Maasai Reasoning.” In The Walking Larder: Patterns of Domestication, Pastoralism, and Predation, edited by J. Clutton-Brock, 598–640. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Galvin, S. S. 2018. “Interspecies Relations and Agrarian Worlds.” Annual Review of Anthropology 47 (1): 233–249. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-102317-050232

- Gardner, B. 2016. Selling the Serengeti: The Cultural Politics of Safari Tourism. Athens: University of Georgia.

- Gates, B. 2018. Climate Change and the 75% Problem. gatesnotes.com.

- Gerber, P. J., H. Steinfeld, B. Henderson, A. Morret, C. Opio, J. Dijkman, A. Falucci, and G. Tempio. 2013. Tackling Climate Change through Livestock: A Global Assessment of Emissions and Mitigation Opportunities. Rome: FAO.

- Getz, W. R., H. G. Hutchison, M. L. Kyomo, A. M. Macha, and D. B. Mpiri. 1986. “Development of a Dual-Purpose Cattle Composite in the Tropics.” In Proceedings of the Third World Congress on Genetics Applied to Livestock Production, edited by G. E. Dickerson, and R. K. Johnson, 493–498. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources.

- Gillespie, K., and R.-C. Collard. 2015. Critical Animal Geographies: Politics, Intersections, and Hierarchies in a Multispecies World. London: Routledge.

- Haraway, D. 1989. Primate Visions: Gender, Race, and Nature in the World of Modern Science. New York: Routledge.

- Hayuma, A. M. 1991. “Management of Communal Natural Resources Affected by Livestock: The Maasai Project in Tanzania.” In Planning for Management of Communal Natural Resources Affected by Livestock. Proceedings from a Workshop for SADCC Countries Held in Mohale’s Hoek on May 28–June 1, 1990, edited by E. M. Portillo, L. C. Weaver, and B. Motsamai, 111–126. Maseru: Range Management Division, Ministry of Agriculture, Cooperatives and Marketing, Lesotho.

- Herrera, P. M., ed. 2020. Extensive Farming and Climate Change: An In-Depth Approach. Valladolid: Fundación Entretantos and Plataforma por la Ganadería Extensiva y el Pastoralismo.

- Herrero, M., P. Havlík, H. Valin, A. Notenbaert, M. C. Rufino, P. K. Thornton, M. Blümmel, F. Weiss, D. Grace, and M. Obersteiner. 2013. “Biomass Use, Production, Feed Efficiencies, and Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Global Livestock Systems.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110 (52): 20888–20893. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1308149110

- Hodgson, D. L. 2001. Once Intrepid Warriors: Gender, Ethnicity, and the Cultural Politics of Maasai Development. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Holloway, L., C. Morris, B. Gilna, and D. Gibbs. 2009. “Biopower, Genetics and Livestock Breeding: (re)constituting Animal Populations and Heterogeneous Biosocial Collectivities.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 34 (3): 394–407. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2009.00347.x

- Homewood, K., and W. A. Rodgers. 1991. Maasailand Ecology: Pastoralist Development and Wildlife Conservation in Ngorongoro, Tanzania. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Houzer, E., and I. Scoones. 2021. Are Livestock Always Bad for the Planet? Rethinking the Protein Transition and Climate Change Debate. Brighton: PASTRES.

- ILRI. 2015. Ethiopia Livestock Master Plan. Nairobi: ILRI.

- ILRI. 2017. Rwanda Livestock Master Plan. Nairobi: ILRI.

- ILRI. 2018. Tanzania Livestock Master Plan. Nairobi: ILRI.

- IPCC. 2019. Climate Change and Land: An IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems. Geneva: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- IPCC. 2021. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kautsky, K. 1988. The Agrarian Question. London and Winchester: Zwan Publications.

- Köhler-Rollefson, I. 2021. Livestock for a Small Planet. Ober-Ramstadt: League for Pastoral Peoples and Endogenous Livestock Development.

- Köhler-Rollefson, I. 2022. Hoofprints on the Land. White River Junction: Chelsea Green Publishing.

- Krätli, S. 2008. “Cattle Breeding, Complexity and Mobility in a Structurally Unpredictable Environment: The WoDaaBe Herders of Niger.” Nomadic Peoples 12 (1): 11–41. https://doi.org/10.3167/np.2008.120102

- Krätli, S., C. Huelsebusch, S. Brooks, and B. Kaufmann. 2013. “Pastoralism: A Critical Asset for Food Security Under Global Climate Change.” Animal Frontiers 3 (1): 42–50. https://doi.org/10.2527/af.2013-0007

- Land O’Lakes. 2007. Tanzania Dairy Enterprise Initiative Final Report. St. Paul: Land O’Lakes Inc.

- Lane, C. 1994. Pastures Lost: Barabaig Economy, Resource Tenure, and the Alienation of Their Land in Tanzania. London: IIED.

- Leach, M., and R. Mearns. 1996. The Lie of the Land: Challenging Received Wisdom on the African Environment. Oxford: James Currey.

- Manzano, P., and J. E. Malo. 2006. “Extreme Long-Distance Seed Dispersal Via Sheep.” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 4 (5): 244–248. https://doi.org/10.1890/1540-9295(2006)004[0244:ELSDVS]2.0.CO;2

- Manzano, P., and S. White. 2019. “Intensifying Pastoralism May Not Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Wildlife-Dominated Landscape Scenarios as a Baseline in Life-Cycle Analysis.” Climate Research 77 (2): 91–97. https://doi.org/10.3354/cr01555

- McGregor, A., L. Rickards, D. Houston, M. K. Goodman, and M. Bojovic. 2021. “The Biopolitics of Cattle Methane Emissions Reduction: Governing Life in a Time of Climate Change.” Antipode 53 (4): 1161–1185. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12714

- McIntire, J., D. Bourzat, and P. Pingali. 1992. Crop-Livestock Interaction in Sub-Saharan Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Mwai, O., O. Hanotte, Y.-J. Kwon, and S. Cho. 2015. “African Indigenous Cattle: Unique Genetic Resources in a Rapidly Changing World.” Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences 28 (7): 911–921. https://doi.org/10.5713/ajas.15.0002R

- Mwatwara, W., and S. Swart. 2016. “‘Better Breeds?’ The Colonial State, Africans and the Cattle Quality Clause in Southern Rhodesia, c.1912–1930.” Journal of Southern African Studies 42 (2): 333–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070.2016.1150639

- Ndagala, D. K. 1990. “Pastoralists and the State in Tanzania.” Nomadic Peoples 25/27: 51–64.

- Neo, H., and J. Emel. 2017. Geographies of Meat: Politics, Economy and Culture. London: Routledge.

- Nori, M., and I. Scoones. 2019. “Pastoralism, Uncertainty and Resilience: Global Lessons from the Margins.” Pastoralism 2019 (9): 10.

- Nuttall, P. 2021. “Pat Brown: “Farm Animals are the Most Destructive Technology on Earth”.” The New Statesman.

- Parkipuny, M. Ole. 1979. “Some Crucial Aspects of the Maasai Predicament.” In African Socialism in Practice: The Tanzanian Experience, edited by A. Coulson, 136–157. Nottingham: Spokesman.

- Paul, B. K., J. C. Groot, B. L. Maass, A. M. Notenbaert, M. Herrero, and P. A. Tittonell. 2020. “Improved Feeding and Forages at a Crossroads: Farming Systems Approaches for Sustainable Livestock Development in East Africa.” Outlook on Agriculture 49 (1): 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0030727020906170

- Poore, J., and T. Nemecek. 2018. “Reducing Food’s Environmental Impacts Through Producers and Consumers.” Science 360 (6392): 987–992. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaq0216

- Popkin, B. M. 2003. “The Nutrition Transition in the Developing World.” Development Policy Review 21 (5-6): 581–597. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8659.2003.00225.x

- Raikes, P. 1981. Livestock Development and Policy in East Africa. Uppsala: Scandinavian Institute of African Studies.

- Rosenberg, G. N. 2016. “A Race Suicide among the Hogs: The Biopolitics of Pork in the United States, 1865–1930.” American Quarterly 68 (1): 49–73. https://doi.org/10.1353/aq.2016.0007

- Rostow, W. W. 1960. The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rout, P. K., and B. K. Behera. 2021. “Factors Influencing Livestock Way of Life.” In Sustainability in Ruminant Livestock, edited by P. K. Rout, and B. K. Behera, 117–136. Singapore: Springer.

- Rufino, M. C., P. Brandt, M. Herrero, and K. Butterbach-Bahl. 2014. “Reducing Uncertainty in Nitrogen Budgets for African Livestock Systems.” Environmental Research Letters 9 (10): 105008. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/9/10/105008

- Schneider, M. 2014. “Developing the Meat Grab.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 41 (4): 613–633. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2014.918959

- Scoones, I. 2020. “Pastoralists and Peasants: Perspectives on Agrarian Change.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 48 (1): 1–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2020.1802249

- Scoones, I. 2023. “Confronting Uncertainties in Pastoral Areas: Transforming Development from Control to Care.” Social Anthropology/Anthropologie sociale (2023): 1–19.

- Scott, J. C. 2017. Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Seré, C., and H. Steinfeld. 1995. World Livestock Production Systems: Current Status, Issues and Trends. Rome: FAO.

- Shekighenda, L. 2022. “Tanzania: Livestock, Fisheries Ministry Budget Targets to Commercialise Subsector.” Tanzania Daily News, May 26.

- Shikuku, K. M., R. O. Valdivia, B. K. Paul, C. Mwongera, L. Winowiecki, P. Läderach, M. Herrero, and S. Silvestri. 2017. “Prioritizing Climate-Smart Livestock Technologies in Rural Tanzania: A Minimum Data Approach.” Agricultural Systems 151: 204–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2016.06.004

- Sorenson, M. V., A. Jacobs, E. W. Tisdale, W. V. Swarzenski, and M. Jacob. 1979. Terminal Evaluation of the Masai Livestock and Range Management Project (AID Project No. 621-11-130-093). Washington, DC: DEVRES.

- Steinfeld, H., P. Gerber, T. Wassenaar, V. Castel, M. Rosales, and C. de Haan. 2006. Livestock’s Long Shadow: Environmental Issues and Options. Rome: FAO.

- Sumberg, J. 1998. “Mixed Farming in Africa: The Search for Order, the Search for Sustainability.” Land Use Policy 15 (4): 293–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-8377(98)00022-2

- Sunseri, T. 2013. “A political Ecology of Beef in Colonial Tanzania and the Global Periphery, 1864–1961.” Journal of Historical Geography 39: 29–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhg.2012.08.017

- Sunseri, T. 2015. “The Entangled History of Sadoka (Rinderpest) and Veterinary Science in Tanzania and the Wider World, 1891–1901.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 89 (1): 92–121. https://doi.org/10.1353/bhm.2015.0005

- Syrstad, O. 1990. “Mpwapwa Cattle: An Indo-Euro-African Synthesis.” Tropical Animal Health and Production 22 (1): 17–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02243492

- Taylor, A., and S. Taylor. 2020. “Solidarity Across Species.” Dissent 67 (3): 103–105. https://doi.org/10.1353/dss.2020.0071

- Tilley, H. 2012. Africa as a Living Laboratory: Empire, Development, and the Problem of Scientific Language, 1870-1950. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

- Tsing, A. L., J. Deger, A. K. Saxena, and F. Zhou. 2020. Feral Atlas: The More-Than-Human Anthropocene. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Turner, M. D. 2009. “Capital on the Move: The Changing Relation Between Livestock and Labor in Mali, West Africa.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 40 (5): 746–755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2009.04.002

- Twine, R. 2010. Animals as Biotechnology: Ethics, Sustainability and Critical Animal Studies. London: Earthscan.

- URT. 1997. Agriculture and Livestock Policy. Dar es Salaam: The United Republic of Tanzania.

- URT. 2006. National Livestock Policy. Dar es Salaam: The United Republic of Tanzania.

- URT. 2015. Tanzania Livestock Modernization Initiative. Dar es Salaam: The United Republic of Tanzania.

- URT. 2019. National Compact Strategies and Action Plan to Implement Global Plan of Action for Animal Genetic Resources in Tanzania. Dodoma: The United Republic of Tanzania.

- URT. 2020. National Sample Census of Agriculture 2019/20. National Report. Dodoma: The United Republic of Tanzania.

- Walwa, W. J. 2020. “Growing Farmer-Herder Conflicts in Tanzania: The Licenced Exclusions of Pastoral Communities Interests Over Access to Resources.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 47 (2): 366–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2019.1602523

- Weis, A. J. 2013. The Ecological Hoofprint: The Global Burden of Industrial Livestock. London: Zed Books.

- Wilcox, S., and S. Rutherford. 2018. Historical Animal Geographies. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Wilson, R. T. 2018. “Crossbreeding of Cattle in Africa.” Journal of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences 6 (1): 16–31. https://doi.org/10.15640/jaes.v7n1a3

- Wolmer, W., and I. Scoones. 2000. “The Science of ‘Civilized’ Agriculture: The Mixed Farming Discourse in Zimbabwe.” African Affairs 99 (397): 575–600. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/99.397.575

- Yurco, K. 2022. “Pastoralist Milking Spaces as Multispecies Sites of Gendered Control and Resistance in Kenya.” Gender, Place & Culture 30 (10): 1–22.