Abstract

In the 1930s Japan developed a death cult which had a profound effect on the conduct of the Japanese armed forces in the Pacific War, 1941–1945. As a result of government directed propaganda campaign after the overthrow of the Shogunate in 1868, the ruling military cliques restored an Imperial system of government which placed Emperor Meiji as the Godhead central to the constitution and spiritual life of the Japanese nation. A bastardised Bushido cult emerged. It combined with a Social-Darwinist belief in Japan's manifest destiny to dominate Asia. The result was a murderous brutality that became synonymous with Japanese treatment of prisoners of war and conquered civilians. Japan's death cult was equally driven by a belief in self-sacrifice characterised by suicidal Banzai charges and kamikaze attacks. The result was kill ratios of Japanese troops in the Pacific War that were unique in the history of warfare. Even Japanese civilians were expected to sacrifice their lives in equal measure in the defence of the homeland. It was for this reason that American war planners came to the shocking estimate that as many as 900,000 Allied troops could die in the conquest of mainland Japan – Operation DOWNFALL. Contrary to the view of numbers of revisionist historians in the post-war period, who have variously argued that the atom bombs were used to prevent Soviet entry into the war against Japan, Francis Pike, author of Hirohito's War, The Pacific War, 1941 – 1945 [Bloomsbury 2015] reaffirms that the nuclear weapon was used for one purpose alone – to bring the war to a speedy end and to save the lives of American troops.

The atom bomb debate

With recent atrocities by ISIS jihadists in Istanbul, Egypt and Paris, it is a timely moment to remember that death cults – the worship and glorification of killing and being killed – are not unique to the Islamic world. In recent history the West has had to deal with the death cults of other cultures. The outstanding example is Japan in the period leading up to and including the Second World War, when that country's death cult was brought to an end by America's atom bomb.

There are few subjects in modern history as contentious as the decision to drop the atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan in 1945. There is no doubt that the Pacific War came to an end soon afterwards with Emperor Hirohito's announcement of surrender. But could that have been achieved in other ways, involving fewer military and civilian deaths?

The post-war justification by President Harry Truman and the Secretary of War, Henry Stimson, the key decision-makers for the dropping of the atom bomb, was simply that it was used to end the war speedily and in the process saved hundreds of thousands of American lives. Subsequently it was also claimed that the atom bombs saved Japanese lives. One of Hirohito's key advisors, Marquis Koichi Kido, keeper of the Privy Seal, later testified that the atom bomb saved “twenty million of my innocent compatriots”Footnote1 though, as General Curtis LeMay, commander of all strategic air operations against Japan, pointed out, “We didn't give a damn about them at the time”.Footnote2

After the war the ‘traditional' view of the reasons for dropping the atom bomb has come under heavy attack, particularly from liberal and New Left historians such as Gar Aperovitz, Barton Bernstein, Martin Sherwin and Kai Bird, who in an op-ed piece for the New York Times in October 1994 wrote that American veterans were “being fooled into believing that the atomic bomb saved them from sacrificing their lives in an invasion of Japan”.Footnote3 These revisionist historians have been joined in their campaign to discredit the Truman presidency's motives for dropping the atom bomb by anti-capitalist commentators such as Noam Chomsky and Gabriel Kolko. Some Japanese historians such as Tsuyoshi Hasegawa have supported them.

The arguments of the revisionists are various: that dropping the atom bomb was unnecessary because a conventional conquest of Japan could have been done at minimal loss of life; that the motives for dropping the atom bomb were political and not related to projections of casualties; that the alternative to dropping the bomb, by making it clear to the Japanese government that the Emperor would be retained, was never seriously explored; and that without the bomb Japan would anyway have surrendered to conventional bombing before the planned start of Operation Olympic on 1 November.

The reasons for claiming that the decisions were political are: that Truman was told at a meeting in June 1945 that there would only be 45,000 American casualties during the planned invasion of Kyushu (Operation Olympic – the first stage of the conquest invasion of Japan, Operation Downfall); and that the Soviet invasion of Manchuria on 9 August 1945, not the atom bomb, was the key determinant of Japan's eventual surrender. In other words the atom bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki to warn off the Soviet Union in both Central Europe and Northern China.

The object of this article is to counter the core argument of the revisionists – that the estimated casualties of the invasion of Japan (Operation Downfall) were so small that the justification for dropping the atom bomb could only have been political – and to re-emphasise the ‘traditional' view that, while Truman and American leaders were aware of the geopolitical uses of the atom bomb, the sole reason for their use was to save American lives and bring the war to an end as quickly as possible. It will be argued that the revisionists, through a lack of understanding, not only of the ubiquitous brutality of Japan's neo-Nazi regime with its all-pervasive ‘death cult', but also of the difficulties inherent in an invasion of Japan, have grossly underestimated the likely casualty rates that an invasion of Japan would have incurred.

Logistics and the brutality of the Japanese military

It is one of the mysteries of the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Pacific War that the Japanese Army indulged in a level of barbarity in the treatment of their prisoners of war and conquered civilians that was medieval in its cruelty. Like ISIS, the Jihadist death cult of Syrian-Iraqi origin, punishment by beheading was the typical method of murdering enemies. The Rape of Nanking (China's capital city), where the lopping off of Chinese heads became its defining image, has entered the pantheon of atrocities comparable with the sack of Rome by the Visigoths (410), Jerusalem by the first crusaders (1099) and Merv by Genghis Khan (1221). The mystery of Japan's descent into barbarism is compounded by the fact that treatment of prisoners by the Japanese Army and Navy in the First Sino-Japanese War (1895) and the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05) was conspicuously humane. The Japanese Army before the 1930s was scrupulous in its treatment of prisoners of war (POWs).

The contrast just 30 years later is remarkable. Between 25 and 35 million people died in the Pacific War (including the Second Sino-Japanese War) of whom about 5 million were combatants. Large numbers of civilians died of course from the starvation and illness that usually accompanies large-scale conflicts. Much of this civilian catastrophe was caused by a Japanese Army, which, unlike the American Army, lived off the land. Forced requisition of food or payment in a worthless scrip inevitably led to starvation in countries whose agrarian economies operated largely at a subsistence level.

The logistics of war was not only a problem for the Japanese Empire. In Bengal in 1943, it is estimated that as many as 2 million Indians may have died while the British administration in New Delhi focused on the supply of Chiang Kai-shek's armies by an air route, ‘the Hump', over the Himalayas. At the Rape of Nanking (autumn 1937) where as many as 250,000 Chinese are thought to have been raped and butchered, Japanese soldiers admitted that their army did not have enough food to feed its POWs. In anticipation of this problem Lieutenant-General Nakajima “came to Nanking bringing in special Peking Oil for burning bodies”.Footnote4

For the Japanese armed forces supply was a constant problem throughout the Pacific War. Japan's political and military leaders had gone to war as a direct consequence of their invasion of Southern Indochina, as a result of which President Roosevelt authorised a financial freeze in July 1941. It was an action that de facto implemented a complete cut in the supply of oil to Japan, which depended on Standard Oil of California (SOCOL) for 80 per cent of its supply. The ultimate aim of Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor and US forces stationed in the Philippines was to get at the oil supplies of the Dutch East Indies, which, though it only supplied 7.5 per cent of the world's oil compared to 62 per cent from America, could nevertheless theoretically counterbalance the missing US supplies, without which Japan's war of attrition in central China would have been unsustainable.

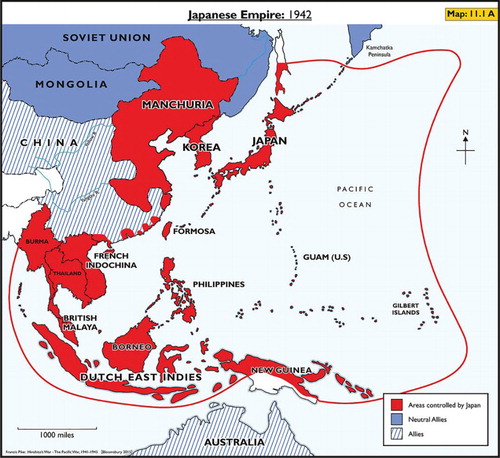

During the course of the Pacific War, Japan failed to bring enough oil from the Dutch East Indies not only because it lacked skilled oil technicians but also because it did not have enough tankers to collect and deliver oil either to Japan or to its far-flung forces. By the summer of 1942, Japan's newly acquired Empire ranged from the Burma-India border in the west, the Solomon Islands in the south, to the Caroline and Gilbert Island in the east and Attu in Alaska. At the start of the Pacific War Japan had just 49 tankers compared to a combined total of over 800 for the US and Great Britain. Indeed before 1941, over 30 per cent of Japan's oil was shipped by foreign carriers.

If the supply of oil was problematic so too was the supply of food and the ships to deliver it. Merchant marine construction, like most civilian areas of the Japanese economy, had been significantly squeezed out by the build-up of naval capacity in the late 1930s. In 1936 Japanese shipyards produced 442,000 tons of merchant shipping versus just 55,000 tons of warships. By 1941 the tonnage of merchant shipping had almost halved to 237,000 tons while the tonnage of warships built had quadrupled to 225,000 tons. As the war progressed, in spite of a significant ramp-up in merchant ship building in 1943–1944, supply worsened as Japan's merchant fleet suffered net loss of cargo capacity in every quarter of the Pacific War from January 1942 onwards. Net merchantman losses amounted to an average of 200,000 tons per quarter in 1942, 250,000 tons per quarter in 1943 before exploding to 500,000 tons per quarter in 1944.

General Yamashita won his superb Malaya campaign in spite of almost overwhelming logistical problems. Britain's colony was conquered in a series of flanking manoeuvers that displayed dazzling tactical brilliance. Yamashita's rapid advance was needed to capture Allied supplies (or, as the Japanese troops called them, ‘Churchill Stores') in order to feed his troops. Noticeably whenever the Japanese Army overran an Allied position in the Pacific War, their advance troops would invariably make their way first to the kitchens and supply stores. Yamashita even decided to leave one division behind because he did not have the logistics to provide for his troops. By the time the Japanese entered Singapore after their whirlwind campaign, Yamashita was out of fresh troops, food and even bullets.

The shortage of food for the Japanese Army was unrelenting as the Pacific War progressed. General Adachii, during his campaigns in Papua New Guinea, was unable sustain his troops in the field. Along the Kokoda Trail Japanese troops resorted to cannibalism and not just on an opportunistic base. In some cases there was clear evidence of institutionalised harvesting of captured Australian troops for battalion canteens. As Lieutenant Sakimoto noted in his diary on 19 October 1943, “Because of food shortages, some companies have been eating the flesh of Australian soldiers”.Footnote5 In addition to the ‘White pigs’, as the Japanese referred to Caucasians, Papuan natives, ‘Black Pigs', were also eaten by the Japanese. On one occasion an advancing Australian soldier found his best mate half cooked in a Japanese stewpot.

Of the 160,000 troops that were sent to fight in New Guinea it is estimated that as few as 8,000 eventually returned to Japan alive. For every Japanese soldier killed by an American weapon during this campaign, more than ten died of disease and starvation. Even where there was little fighting Japanese soldiers died in droves. The Solomon Islands campaign ending on the island of Bougainville was similarly harsh on Japanese troops. Of the 65,000 Japanese soldiers on the island at the time of Admiral Halsey's establishment of airfields and a secure cantonment on Empress Augusta Bay, only 21,000 remained alive by the time of Emperor Hirohito's surrender on 15 August 1945. While some 8,000 died in the initial attempts to retake Empress Augusta Bay, 36,000 Japanese troops eventually succumbed to starvation on Bougainville. Cut off from Japan, the Japanese Army there could not sustain itself. In April 1944 Japanese troops’ rations on Bougainville were reduced to 250 grams of rice from the standard issue of 750 grams per day. But six months later there was no rice at all.

In looking at the death and brutality meted out to both conquered civilians and prisoners of war (POWs) it is therefore at least worth noting that the behaviour of Japanese troops did reflect the conditions that they too experienced. By all accounts, life in the Japanese army was brutal. Apart from the lack of food and medical care, military discipline was imposed by vicious beatings down the chain of command. It seems that Koreans drafted into the Japanese Army, who were frequently used as POW guards, were as cruel as the Japanese and were themselves abused and beaten cruelly by their Japanese commanders. It was a background of brutalisation and desensitisation that was conducive to the development of a death cult.

Imperial expansion, social control and Unit 731

The earlier rapid physical expansion of the Japanese Empire in northern and central China at the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War, bringing with it problems of logistics and control, may itself have been a driver of the later brutality in South East Asia and the South Pacific. Compared to the earlier 19th- and 20th-century acquisitions of the Ryukyu Islands, the Kuril and Bonin Islands, Formosa, Korea and Manchuria, the conquest of northern and central China, which included its most prosperous cities, was an enormous military and logistical undertaking. At a stroke the size of Japan's empire in terms of population tripled.

Before the start of the Sino-Japanese War in July 1937 Japan and its empire comprised approximately 125m people. Within a year the Japanese Empire comprised 375m people with the addition of some 250m Chinese ruled by a puppet government in Nanking. For the next four years, moreover, Japan would battle the other half of the Chinese population in a war of attrition that was a far cry from the four-month campaign promised to Hirohito by his military commanders. The landmass of Japan's empire also doubled.

Control of this vast new empire was maintained by brutality and suppression. Perhaps it was the only viable method given the scale of the military and logistical task, which eventually absorbed more than 1.5m Japanese troops. The mass slaughter of Chinese citizens was in part a means of keeping others in line. In some cases it was a matter of self-preservation. In his diary, Shiro Azuma noted of the Rape of Nanking, “Although, we had two companies, and those seven thousand prisoners had already been disarmed, our troops could have been annihilated had they decided to rise up and revolt”.Footnote6

Japanese brutality reached its apogee with the development of special units, which were authorised by the government in Tokyo to carry out human experimentation. Resignation from the League of Nations in 1932, as a result of criticism from the Lytton Report blaming Japan for the aggressive occupation of Manchuria, provided Dr. Shiro Ishii with an opportune moment to bid for funding for research in biological warfare. Facilities were subsequently established near Harbin in Manchuria.

Unit 731, as it became known in August 1935, treated its prisoners to various forms of experimentation relating to disease, blood products as well as conditions such as frostbite. Researchers privately joked, “the people are logs (maruta)”.Footnote7 The name stuck. Thereafter prisoners were referred to by number; as one researcher noted, “They are counted not as one person or two persons but ‘one log, two logs'. We are not concerned with where they are from, how they came here”.Footnote8 Unit 731's most notorious activity was live human vivisection.

Satellite facilities had other specialities. Unit 100, managed by veterinarian Yujiro Wakamatsu, specialised in producing pathogens such as glanders and anthrax. The targets of his research were horses and other edible animals of the Chinese and Soviet Armies. At Anda, three hours from Unit 731, outdoor experiments on Chinese villages were conducted using pathogens. Tests were also carried out on prisoners using poison gasses. Nami Unit 8604, established at Guangzhou in 1938, carried out experiments for the spreading of bubonic plague. Development of plague pathogens was also a major activity of the Beijing-based Unit 1855. Employee Choi Hyung Shin recalled, “In the plague tests, the prisoners suffered with chills and fever, and groaned in pain … until they died. From what I saw, one person was killed every day”.Footnote9 Cholera and epidemic haemorrhagic fever were also used in human experiments. It was later estimated that 400,000 Chinese citizens were killed by pathogens dropped on Chinese towns and villages by Japanese aircraft.

The operation of experimentation units may have been covert but they were widely known about in the higher echelons of command in Tokyo. Prime Minister Hideki Tojo, a former head of the kempeitei (Military Secret Police) in Manchuria, was so delighted with Ishii's work that Hirohito was persuaded to award Dr. Ishii, by now a general, a special service decoration. It is also known from his memoirs that Prince Mikasa, Hirohito's youngest brother, visited Ishii's operation and it seems highly unlikely that the Emperor was ignorant of his army's activities. The organisation of human experimentation units was symptomatic of the dehumanisation of non-Japanese people that was implicit in the ultranationalist doctrines promoted by Japan's pre-war government.

By August 1945 the atrocities being committed by Japan's forces were well known to President Truman and Allied leaders. Relief of the suffering of POWs was becoming an issue of journalistic interest. MacArthur's dispatch of a flying column to save the prisoners at Santa Tomas internment camp north of Manila in February 1945 was an indication of how seriously the US military took the threat of atrocities in POW camps at the end of the war.

There was a clear fear on the part of the Allies that in a protracted battle for Japan, POWs would be massacred. Indeed Allied prisoners at the Japanese cantonment of Kavieng on New Ireland were murdered when an invasion of the island was expected. After the war the war crimes tribunal in Melbourne recorded that Corporal Horiguchi, whose defence pleaded that he was under orders, took each victim to the wharf: “Sailors then placed a noose of rope over the victim's head and strangled him. The bodies were then thrown into one of two barges and cement sinkers were secured to the bodies by wire cable”.Footnote10 Similarly on Palawan, the Japanese commander executed all POWs when he learnt, erroneously as it turned out, that the Allies were about to invade this Philippine island. The 150 prisoners at Puerto Princesa were burnt alive in trenches or machine gunned as they tried to escape.

Would the same fate have befallen POWs in Japan if its home islands had been invaded? Orders found after the war seem to confirm that there was a general policy to kill all POWs and civilian internees – some 130,000 people in total. The anticipated murder of allied POWs did not just relate to Japan. It is thought that the planned Allied invasion of Thailand on 18 August would have triggered a mass execution of prisoners held there.

Japan, racism and the Geneva Convention

If failures in logistics and the problems of control go some way to explaining some aspects of Japanese barbarity they are not enough to explain the vast panoply of war crimes committed during the Pacific War. Even when food was plentiful, the treatment of civilians and POWs was harsh. In an analysis of the 100 most significant recorded massacres of civilians and POWs in the Pacific War, it is noticeable that these events were distributed across all countries, 12 including Japan, under Japanese control and across every year of the war – though the first year (1942) and final year (7 months of 1945) saw a ramping up of atrocities.

An analysis of Allied POWs in Japanese prison camps is also revealing. It may come as a surprise that British POWs, albeit cruelly treated, fared relatively well. While some 24 per cent of British POWs died in Japanese captivity, which compares with just 4 per cent of British POWs in German prisoner of war camps, American POWs suffered a 32 per cent death rate. As for Indian POWs, by far the largest POW population in Japanese camps – more than 60,000 – they suffered a more than 50 per cent death rate. It did not help that Japanese troops would use Indian soldiers for target practice. To put the comparatives in a fair perspective, it might also be noted that on Germany's Eastern front in World War II, the German Army killed 60 per cent of its Soviet POWs. Japan was not the only country inclined to racism in its differentiated handling of POWs.

Racism cut both ways. At the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century Japanese immigrant settlers were the subject of racial laws that prevented Asians from owning land in the United States. These laws, passed in 13 states, did not apply to Europeans, who accounted for the bulk of immigration. Much commented on in the Japanese press, the US immigration laws began to impress upon Japan's consciousness that they could not expect a fair deal from the West.

The Triple Intervention in 1906, when Germany, France and Russia strong-armed Japan into giving up the Liaodong Peninsula in Manchuria that it had won at the Treaty of Shimonoseki (1905) after the defeat of China in the First Sino Japanese War, also aroused anti-Western passions. Kametaro Mitsukawa, one of the most influential ultranationalist intellectuals of the pre-war period, went so far as to title his biography After the Triple Intervention (1935), thus highlighting a humiliation that initiated his personal crusade in favour of a pan-Asian response to Western encroachment. Some would also interpret the disappointing gains made by Japan at the Treaty of Portsmouth after their crushing victory over Russia in 1905, as a sign of President Teddy Roosevelt's racial preference and bad faith in his role as go-between in the peace negotiations.

Nevertheless, Japan appeared to be a fully signed-up member of the new international order that emerged from the wreckage of World War I. Apart from being an important presence at the Treaty of Versailles, Japan was treated as one of the key participants at the Washington Conference, the naval arms limitation treaty which agreed a capital ships ration of 5:5:3 for the US, Great Britain and Japan respectively. By comparison France and Italy were allocated a ratio of just 1.5 each.

But it was an increasing reluctance to embrace Western rules that led Japan to effectively repudiate the Hague Convention when the Vice-Minister of the Navy recommended that the 1929 Geneva Convention should not be ratified. Japan had previously signed and ratified the Hague Conventions (1899 and 1907), whose provisions included the Geneva Convention 1864), which laid down rules for the treatment of prisoners of war. Thus Japan went into the Sino-Japanese War and Pacific War without the restraint of international laws on treatment of prisoners.

Curiously America, which had treated Japan as the plucky underdog in the war against Imperial Russia, almost immediately reversed its feelings toward Japan in the aftermath of their victory. Indeed historians Tal Tovy and Sharon Halvi have argued that “a proto-cold war existed from the end of the Russo-Japanese War until the outbreak of World War II … .”Footnote11 Europeans too were stirred to fearful racial stereotyping. A Frenchman, De Lannesan, writing in Le Siècle, expressed feelings that were to become increasingly prevalent in Europe when he wrote, “Japan is a child people. Now that it has huge toys like battleships, it is not reasonable enough, not old enough not to try them … despite their borrowings from Western civilisation the Japanese remain barbarians.”Footnote12 After the Russo-Japanese War even the British, Japan's closest allies, were concerned at the sudden power shift; the noted diplomat and Japanologist Sir Ernest Satow observed, “The rise of Japan has completely upset our equilibrium as a new planet the size of Mars would derange our solar system”.Footnote13

In spite of Japan's clear elevation above two major European powers in the Washington Conference allocations, ultranationalist elements within the military resented the restraints put on Japan's naval expansion. The allowed ratio of capital ships favouring the United States and the United Kingdom appeared to many Japanese to be an Anglo-Saxon anti-Japanese stitch-up. In response Mitsukawa feared that the Western powers were “plotting to subjugate Asia completely by the end of the 20th century”.Footnote14

The Meiji restoration and the origins of a death cult

Racial resentment was only part of the background to the development of a death cult within the Japanese military. Like all revolutionaries, the leaders of the four domains, the Satsuma, Choshu, Tosa and Saba, which overthrew the Shogunate in 1868, sought to justify their insurrection. Although the overthrow of the 265-year-old Tokugawa Shogunate was a result of power politics, it was convenient to market their overthrow as a restoration of the Meiji Emperor rather than as a revolution.

Nevertheless it was a restoration that embedded the Army (dominated by the Choshu) and the Navy (dominated by the Satsuma) into the constitution and promoted the Emperor as Supreme Commander. The Meiji Constitution, promulgated in 1889, affirmed that the Emperor stood in an unbroken line of succession, sacred blood lineage, based on male descendants, and that government was subordinated to monarchy on that basis. It defined him as “sacred and inviolable”, “head of empire” (genshu), supreme commander (daigensu) of the armed forces, and superintendent of all powers of sovereignty. He could convoke and dissolve the Imperial Diet, issue imperial ordinances in place of law and appoint and dismiss ministers of state, civil officials and military officers and determine their salaries.

The Emperor of Japan had always been a ‘God' in Japanese mythology but the importance of the myth had been in abeyance during the Shogun epoch. The restoration brought the Emperor as godhead to centre-stage. Apart from the new Meiji Constitution there were two key planks to national indoctrination. In 1882 the Imperial Rescript to Soldiers and Sailors (Gunjin Chokyuyu) forced recruits to learn by rote a 2,700 Kanji peon to the Emperor, which invoked the precept “duty is heavier than a mountain; death is lighter than a feather”.Footnote15 In the years ahead the military rescript was the heart of national service and invoked in bastardised form the warrior spirit of Bushido with its emphasis on honour in death.

It is no coincidence that by the 1930s, when Japanese imperial expansion began to reach its zenith, the leaders of the Army and Navy were the early recruits who had learnt the Gunjin Chokyuyu. As General Tojo, Japan's wartime prime minister would assert, “The Emperor is the Godhead … and we, no matter how hard we strive as ministers, are nothing more than human”.Footnote16 The Emperor-focused religious drive was so strongly embedded that many Japanese commanders, including the infamous Admiral Yamamoto, would offer daily prayers facing toward the Imperial Palace just as Muslims turn toward Mecca.

Meanwhile the propaganda message of Imperial divinity was driven home with equal force in schools after the issuance of the Imperials Rescript on education. In the post-Meiji-restoration period, the divine position of the Emperor was put at the heart of an all-encompassing state philosophy and in the Pacific War Hirohito was the idol for which 1.5m Japanese soldiers would die. For many of the Emperor's troops their final words in desperate suicide charges were Tenno Heika Banzai! (Long Live the Emperor!).

Added to this heady mix of pseudo-religious and state propaganda was the idea that Japan had to create a pan-Asian Empire or Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere to protect itself from the advancing Western empires. It is clear that by the 1930s important power blocks in the Japanese constitution, the Emperor and his court, the bureaucracy, the armed forces, the press, the intelligentsia and the vast majority of the populace had imbued a belief in racial superiority, bastardised bushido ideals and a social-Darwinist view that in a fight for the survival of the fittest, Japan was bestowed with a manifest destiny to dominate Asia.

Kamikaze – the death cult in practice

To die for love of country is as much a tradition of Western culture as for Japan. Leonidas, the Spartan king, has been an iconic figure in European culture since he and his 300 Spartans in an act of suicidal bravery held up the invasion of Greece by Xerxes's Persian Army at the Battle of Thermopylae (480 BC). In more modern mythology, Americans are taught to revere the suicidal sacrifice of those men who fought for an independent Texas at the Battle of the Alamo (1836) against Santa Anna's Mexican Army, which was attempting to put down an insurrection by American settlers. In Britain the blind obedience to the mistaken order that sent Lord Cardigan and the Light Brigade on their suicidal frontal charge against Russian artillery at the Battle of Balaclava is celebrated in Alfred Lord Tennyson's famous poem, The Charge of the Light Brigade (1854).

World War II was no different. Indeed Nazi Germany's volunteer suicide pilots were known as the Leonidas Squadron. Stalin also exhorted pilots to crash into German bombers. After Lieutenant Leonid Butelin severed the tail of a Junkers-88 bomber with his propeller, hundreds followed his example and in America Life magazine ran a laudatory essay on the subject of the “Russian Rammers”. Curiously in the Pacific War, the first suicide pilot was probably a British flier, who deliberately crashed his damaged plane into a Japanese troop transport at Koto Bharu in Northern Malaya on 8 December 1941.

Japanese kamikaze pilots also had individual beginnings. The first recorded attack was on HMAS Australia, a heavy cruiser, on 21 October, shortly before the Battle of Leyte Gulf. Three days later a Mitsubishi G4M bomber crashed into USS Sonoma and sank it. However, a few months earlier Captain Eiichiro Jyo, Captain of the carrier Chiyoda, had submitted the idea of Special Attack Units after he witnessed the crushing defeat of Japanese naval air power at the Battle of the Philippine Sea (June 1944). The use of kamikaze as a battle tactic came when First Air Fleet Admiral Takijiro Onishi announced to his officers at Mabalacat Airfield on Luzon Island, “In my opinion the enemy can be stopped only by crashing on their carrier decks with Zero fighters carrying bombs”.Footnote17 The aftermath of the Battle of Leyte Gulf saw the formal adoption of Special Attack Units.

After initial successes in attacks on the US fleet off the Philippines, the organisation of kamikaze squadrons became one of the central planks of Japan's defence of its home islands. When the US finally invaded Okinawa its fleet was subject to 1,500 kamikaze attacks. Some 150 ships were hit and more than 4,900 American sailors were killed. It is a measure of the industrial scale of the kamikaze squadrons that in preparing for the US invasion of Japan there were 12,700 aircraft and tens of thousands of volunteers prepared for suicide missions. Although some pilots were reluctantly volunteered for kamikaze squadrons – one was even found chained to his cockpit while another was shot for baulking at his task nine times – most went cheerfully to their deaths. Lieutenant Shunsaku Tsuji was typical of the breed of ultranationalist devotees; after spending a last evening with friends he asked his hosts to “inform my family that I departed on my last mission full of joy after I feasted on udon (Japanese noodles)”.Footnote18

The whole country was co-opted to support the kamikaze. Classes of schoolgirls presented flowers and waved off kamikaze pilots. Religious rites were offered. A ritual last cup of sake was drunk. Religious words were spoken. A white cotton hachimaki (headband) usually inscribed with the word kamikaze was fixed around the forehead. Some pilots apparently took off inebriated – a feature too of Banzai charges. Newspapers lauded their heroic actions. “The spirit of the Special Attack Corps is the great spirit that runs in the blood of every Japanese”,Footnote19 wrote the Nippon Times.

In addition to kamikaze, the Japanese Navy also invested in suicide submarines known as kaiten as well as shinyo (suicide speed boats) and manned Long Lance Type 97 Torpedoes. In October 1944, when Captain Miyazaki, chief instructor at Kawatana Naval Training School, asked for volunteers, 150 out of 400 students chose to train as kaiten pilots. It was a strategy that was a logical development of the militarists’ belief that Yamato Damashii (the Spirt of Japan) could overcome all obstacles, including its material deficiencies vis-à-vis the United States.

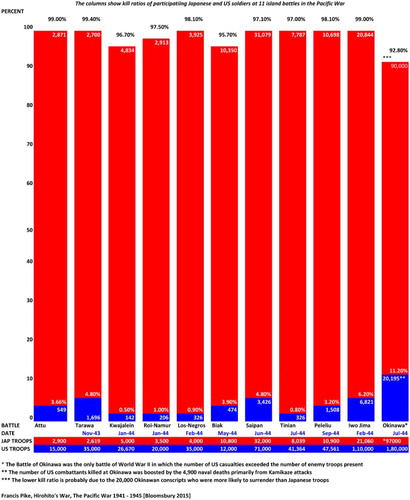

Suicide was implicit in the 1882 Military Rescript, which did not allow for the concept of surrender, and in practice suicide had been practised as a last resort in combat as early as 1942. The famed Banzai charges that characterised every military setback from as early as the summer of 1942 at the Battle of Milne Bay on the southeastern tip of Papua New Guinea and at the Battle of Tenaru on Guadalcanal Island were in effect suicide missions. Those who did not die in a death charge would often shoot themselves in preference to surrender, which was strictly forbidden in the Japanese soldiers’ code. At the Battle of Tarawa, the first Central Pacific island battle, soldiers were found with their heads blown off as they triggered their Arisaka rifles with their toes. Of the 2,700 Japanese combatants at Tarawa, just 17 were taken alive – a 99.4 per cent kill ratio.

The Japanese Navy, sometimes mistakenly painted as more dovish and enlightened than the army, was equally fanatical. Often Japanese sailors found in the water after naval battles would refuse to be rescued and sometimes begged to be shot. The Japanese Navy, which first proposed kamikaze as a war tactic, also launched the most spectacular suicide mission of the war when the super-battleship Yamato was given enough fuel for a one-way mission to Okinawa. After being riddled with torpedoes and bombs, the Yamato sank with 3,000 sailors aboard. Just a handful of sailors were picked up alive.

It was not just Japanese combatants that were expected to sacrifice their lives. Wives of kamikaze pilots sometimes killed themselves just as by tradition Indian wives committed suttee (self-immolation) on their husbands’ funeral pyre; when circumstances allowed other Japanese wives hopped into the cockpit with their spouses and joined them in their kamikaze missions. On Saipan, American troops watched in astonishment on 9 July 1944 as hundreds of islanders, mainly women and children, threw themselves off Morubi Cliffs, which rose 800 feet from the sea. An officer on a minesweeper reported on the spectacle, “Part of the sea was so congested with floating bodies we simply can't avoid running them down … [one girl] had drowned herself while giving birth to a baby”.Footnote20 A week earlier the civilian population of the island had received an Imperial Rescript exhorting them to commit suicide; they were promised a status in death equal to that of soldiers – a Shinto equivalent of the blandishments famously offered to Jihadi martyrs.

Similar mass civilian suicide was also recorded on Okinawa, where women and children, in some reported incidents, were pushed in front of Japanese troops. It is estimated that 150,000 Okinawans were killed, 25 per cent of the island's population. The numbers are all the more remarkable for the fact that the Okinawans were not Japanese and were often hostile to a nation that had annexed the Ryukyu kingdom in 1879. Although the Japanese Ministry of Education has removed references to the Army's instigation of mass suicide on Okinawa, in 2008 an Osaka Prefecture court ruled, “It can be said the military was deeply involved in the mass suicides”.Footnote21 The verdict supported the campaign by the Nobel-prize-winning novelist Kenzaburo Oe to make known the atrocities on Okinawa.

Although, as has been illustrated, self-sacrifice in battle is a normal phenomenon across most cultures, Japan's military and civilian population had by the start of the Pacific War taken what was essentially an act of individual self-sacrifice and made it part of an institutionalised state-sponsored death cult; suicide by Japanese forces during the Pacific War became a religious and ideological practice that was quantitatively and qualitatively different from individual heroism in battle.

The collective nature of the death cult is well illustrated by the death of Admiral Ugaki – the last kamikaze. After Hirohito's surrender announcement, he insisted on making a final kamikaze attack, telling his chief of staff, “Please allow me the right to choose my own death. This is my last chance to die like a warrior”.Footnote22 The war was over but when Ugaki arrived at the airfield he found that every member of the 12-man squadron was prepared to accompany him – the twelfth man whose aircraft Ugaki had requisitioned insisted on squeezing into the same cockpit as his commander. In a last radio message, Ugaki urged Japan to “rebuild a strong armed force, and make our Empire last forever. The Emperor, Banzai!”Footnote23

Kill rates of Japanese soldiers in the island battles of the Pacific War

The consequences of Japan's death cult were extraordinarily reflected in the unique death rates in the Japanese armed forces.

It is interesting to make some comparisons between battles in the Pacific and battles in Europe during World War II. Perhaps the most famous battle involving British troops in World War II was the Battle of El Alamein. A British Army led by General Montgomery in North Africa defeated approximately 100,000 German and Italian troops, of whom about 5,000 were killed. By contrast when General Slim faced a 100,000-strong Japanese army at the linked Battles of Imphal and Kohima, an estimated 70,000 Japanese soldiers died – a 70 per cent death rate versus 5 per cent in North Africa. In large part the extraordinary death rate reflected Japanese generals’ disregard for the lives of their soldiers; at the Battle of Kohima Lieutenant-General Kotoku Sato's requests to retreat, in spite of his troops having run out of food to sustain them, were repeatedly denied by General Mutaguchi.

It was not just the Japanese foot soldier who was treated as little more than battle fodder. Long-distance flying in World War II aircraft in tropical conditions was exhausting and stressful even without the dangers of aerial combat. With Japan's increasingly outdated and clapped-out aircraft – no match for the new US aircraft after 1943 – the odds of survival for a Japanese pilot were small. Japan's fliers flew until they died. With no cabin armour, Japanese fighter aircraft were designed for pilots who were expendable. Not that they complained – indeed many refused to carry parachutes, which they regarded as a dereliction of the Bushido code. By the Battle of Bougainville in the summer of 1943, US kill rates rose as high as 10 to 1 in the air. By comparison American fliers, whose aircraft were heavily armoured, were given furlough ever six weeks. In spite of the uninspiring diet, they were also well fed and occasionally even supplied with a bottle of beer. Unlike Japanese pilots, US fliers could also rely on a sophisticated search and rescue service if they were shot down.

But it is in the island battles that the unique characteristics of Japanese military culture showed themselves most clearly. On an island there was nowhere for Japanese soldiers to retreat. Soldiers could either be captured or die. An analysis of 11 of the main Pacific island battles shows that Japanese soldiers invariably chose death. Death rates in the 11 island battles analysed in Chart A show that of the Japanese soldiers who started these battles the average kill rate was over 97 per cent. Only on Okinawa did that ratio fall to 92 per cent, but that may be largely explained by the presence of 20,000 Okinawan troops who were not as fanatical as their Japanese counterparts.

The kill rates were seemingly unconnected with terrain; they were consistently high whether battles were fought on the flat sugarcane fields of Tinian, the sparse palm tree atolls of the Pacific such as Tarawa, the mountainous jungle-covered island of Peleliu or the mountainous snowy wastes of Attu in Alaska. By comparison western troops are normally considered to be non-functional when casualty rates hit 30 per cent. Even the legendary German Waffen SS units on the Eastern Front only sustained battle competence up to a 60 per cent casualty rate. As General Slim observed, “Everyone talks about fighting to the last man and last round, but only the Japanese actually do it”.Footnote24 It was an observation that necessarily had a profound effect on the calculation of projected casualty rates for the invasion of Japan.

American casualty estimates for Operation Downfall

It is against the background knowledge of the unique characteristics of Japan's death cult and the propensity of Japanese troops to fight to the death that the issue of casualty forecasts for the invasion of Japan needs to be judged.

Writing for the Mises Institute in 2010, historian Ralph Raico restated the revisionist argument regarding casualty estimates: “the worst-case scenario for a full-scale invasion of the Japanese home islands (Operation Downfall) was 46,000 American lives lost.”Footnote25 In effect it was an endorsement of Barton Bernstein's conclusions earlier that year in an article entitled A Postwar Myth: 500,000 US Lives Saved. Remarkably the revisionists tend to regard the disposal of 46,000 US lives with casual indifference.

The root of the revisionist argument lies in the casualty figures presented by Admiral King, Admiral Nimitz and General MacArthur's staff at a Joint Chiefs of Staff meeting with President Truman on 18 June. Their estimates for casualties just for the invasion of Kyushu, Japan's southern main island, were just 41,000, 49,000 and 51,000 casualties respectively. From these figures Bernstein extrapolates that deaths for Operation Downfall, the invasion and conquest of Japan's four main islands, would only have been between 20,000 and 46,000. The problem with the Joint Chiefs’ June estimates is that they were made before it became clear from ULTRA intelligence reports that Japan was pouring hundreds of thousands of fresh troops into Kyushu.

The second problem with the Joint Chiefs’ estimates was that both US military and naval commanders had a track record of grossly underestimating American casualties in earlier campaigns. It should be noted that the conquest of Leyte Island in the Philippines had been expected to need four US divisions for a 45-day campaign but needed nine divisions and four months to complete the task. As US forces approached Japan, the divergence between forecast casualties and actual casualties increased.

Yet the experience of the island campaigns and the conquest of Okinawa in April 1945 should have pointed the way to what the human costs would have been had a full-scale of invasion Japan taken place. If American casualties at Okinawa had been replicated pro rata in Operation Downfall the total number of US casualties would have been 2.7m with some 485,000 troops killed. In addition British casualties, usually ignored by American historians, would have been 540,000 with 97,000 deaths – more than a third of British troops who actually died in World War II. Neither do these numbers include the estimated British casualties from the invasion of Thailand planned for 18 August or the likelihood of the murder of Allied POWs and civilian internees.

In another comparative, American casualties per square mile on Okinawa were 160 whereas Barton Bernstein's estimated casualty rate for Operation Downfall assumes fewer than 0.3 casualties per square mile. Moreover terrain and societal factors in Japan were even more conducive to defence than Okinawa.

Heavily forested mountains cover over 80 per cent of the country. Even the Kanto Plain around Tokyo presented severe challenges. The Kanto Plain was not an equivalent of the open fields of Normandy or northern Germany. Waterlogged rice fields and irrigation dykes would have made tank advances extremely difficult, particularly against a Japanese army that was much better provided with anti-tank equipment than on Okinawa; as military historian D.M. Giangreco has pointed out, even on Okinawa relatively poorly equipped Japanese forces were very effective against Sherman tanks.

Japanese forces would have been dug-in on its mainland islands with defence systems that American, Australian and British officers had come to recognise as superb. Japan's army of 4m troops lay in wait for the invaders. Furthermore they would be supported by 25m citizen reserves who were fully inculcated into the death cult promoted by the Japanese government. Officers were confident that in the US landings alone a million casualties could be inflicted. In part their expectations were based on an anticipated improvement in the score ratio of kamikaze on US ships from one hit out of nine to one out of six because of the shortened lines of attack compared to distant Okinawa. On Okinawa 1,465 kamikaze attacks caused damage to 157 Allied ships and inflicted 4,900 deaths out of a total of 9,700 naval casualties. With at least six times as many kamikaze aircraft on the mainland, let alone sea borne kamikaze craft, hits on Allied ships could have been between 900 and 1,200. Even with a planned armada of 3,000 ships, massively exceeding the Normandy landings, Allied losses would have been substantial. Naval casualties from kamikaze attacks alone in the landing phase would almost certainly have exceeded Bernstein's estimates for the entirety of Operation Downfall.

By August 1945 the US Joint Chiefs revised their casualty estimates to 1.3m, which exceeded the 1.0m figures that former President Herbert Hoover had put forward in June. However, William Shockley's estimates were a scale higher. Caltech and MIT physicist and later Nobel Prize winner Dr. William Shockley, who worked as an expert consultant in the office of the Secretary of War, constructed Secretary of War Stimson's figures. His meticulously prepared evaluation gave a range of estimates from a minimum of 1.7m Allied casualties to a maximum of 4m – including 400,000 to 800,000 deaths.

Truman – the decision to drop the atom bomb

Even within America's hierarchy the use of the atom bomb provoked strong reactions. Powerful voices including Admiral Halsey, General MacArthur, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Admiral William Leahy, nuclear scientists Leo Szilard and James Franck and many others at various times expressed alarm at the use of nuclear weapons to defeat Japan. General MacArthur spoke for many when he described the atom bomb as a “Frankenstein monster”.

Soldiers were naturally reluctant to cede final victory to a single weapon that seemingly made all the efforts of their troops apparently redundant. Leahy argued that “in being the first to use it, we had adopted an ethical standard common to the barbarians of the Dark Ages. I was not taught to make war in that fashion, and wars cannot be won by destroying women and children”.Footnote26 It was a desperate cry for a halt to the advance of technology and a return to a mythical age of gentlemanly military engagement. The US military would soon adapt to the new reality of a nuclear age.

However, it is difficult to understand how atom bombing was any more immoral than the conventional bombing of Japan. They were both horrific, as the firebombing of the 8 March Great Tokyo Air Raid – killing almost double the number of the Hiroshima atom bomb on 7 August – clearly demonstrated. In spite of Leahy's view, the special moral differentiation of the atom bomb only became broadly imbued after the end of the War when the effects of radiation sickness became known. In fact Oppenheimer and his team had misjudged the radiation fallout from the first atom bomb test in New Mexico to the extent that General Marshall was considering the use of atom bombs as a tactical weapon for the invasion of Kyushu.

The supporters of the atom bomb's use were no more enamoured of this fiendishly powerful weapon; it was clear to most men that the development of the atom bomb could lead to an arms race and a possible doomsday conflagration. The Franck report, supported by Leo Szilard, came to the obvious conclusion that use of the bomb on Japan would promote an arms race. In reality there already was a nuclear arms race. Truman had told Stalin about America's new weapon during the Potsdam Conference. Within minutes of Truman's revelation of this new weapon, Stalin ordered General Zukhov and his foreign minister Molotov to speed up development of their own bomb. On 25 July Truman wrote in his diary, “We have discovered the most terrible bomb in the history of the world”.Footnote27 Thinking the atom bomb an abominable invention was one thing but deciding not to use it was another matter. As America's president, Truman's overwhelming duty was to the US citizens who had elected him.

With Truman's approval, Secretary of War Stimson set up the Interim Committee charged with considering the use of the atom bomb. To sustain an impartial view of the use of the atom bomb, those intimately involved in the Manhattan Project, including its executive manager Major-General Leslie ‘Dick' Groves, were excluded. The seven additional members included soon-to-be Secretary of State James Byrnes and senior officials from the war departments and the scientific world.

Although Philip Oppenheimer, head of the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos, was not on the Interim Committee, on 16 June he, along with Nobel Prize winner Enrico Fermi and Arthur Compton, advised against using the first atom bomb in a demonstration; they concluded, “We see no acceptable alternative to direct military use”.Footnote28 A passive demonstration would lack psychological impact, which might have undermined the belief that America had the stomach for a full-scale invasion. Secondly there were still doubts whether it would work and more prosaically, at the beginning of August 1945, the US only had two atom bombs – with the prospect of only seven more by the 1 November target date for the launch of Operation Downfall.

The Interim Committee agreed with the importance of psychological impact but concluded that the first atom bomb should be used against a strategic target – hence the decision not to bomb the Imperial Palace, which might have had greater psychological impact but would have had no military justification. Eventually the Target Committee would recommend Hiroshima rather than Kyoto, which Henry Stimson had visited on his honeymoon. Apart from sentimental regard for Kyoto's treasures, he feared that the destruction of Japan's great cultural city would embitter the Japanese toward America in the post-war period. Hiroshima was finally chosen as the target because it was a major Japanese logistical and industrial centre, which was also home to 43,000 Japanese troops of General Hata's Second General Army.

It is indisputable that Truman, Secretary of War Stimson and other American leaders were aware of the geopolitical implications of the atom bomb. Indeed all the major participants in the Manhattan Project discussed the pros and cons of using the atom bomb. However, although Truman reportedly said, “If this explodes as I think it will, I'll certainly have a hammer on those boys”,Footnote29 it was an offhand remark that provides thin gruel for those who think that he ordered the dropping of an atom mainly to take advantage of the Soviet Union.

Inevitably in the post-war period it was a small jump for conspiracists to believe that the real motive for dropping the atom bomb was political – that the US wanted to frighten off the Soviets. Thus British physicist P.M.S. Blackett protested that dropping the bomb was “the first major operation of the cold diplomatic war with Russia”.Footnote30

Other conspiracists have argued that the bomb was dropped to forestall Russia's possible encroachment on both Russia and Japan. Indeed Stalin took Japan's Kuril Islands and Sakhalin even after Hirohito had surrendered. But it should be remembered that President Roosevelt had wanted Soviet participation in the war against Japan and at the Yalta Conference had pressured Stalin into agreeing to declare war on Japan three months after the defeat of Germany. In fact the Soviet Union invaded Manchuria two days behind schedule on 9 August.

Although Truman was beginning to have some concerns about the Soviets’ post-war activities in Eastern Europe, his administration was some way off a full break with Moscow. In August 1945 Truman, whatever his doubts, still considered Stalin as an ally and clung to the belief that they would work together in the post-war period. He wrote privately of his hopes:

To have a reasonable lasting peace the three great powers must be able to trust each other and they must themselves honestly want it. They must also have the confidence of the smaller nations. Russia hasn't the confidence of the smaller nations, nor has Britain. We have. I want peace and I'm willing to fight for it.Footnote31

Even the hawks in his administration, such as Dean Acheson, Under Secretary of State, believed that the secret of nuclear weapons needed to be opened to the World: “What we know is not a secret which we can keep to ourselves … .”Footnote32 Inconveniently for the conspiracy theorists, the West's fallout with the Soviets did not come until George Kennan's famous February 1946 ‘Long Telegram' warned the state department of the Soviets’ long-term expansionist intentions. It was quickly followed by Churchill's equally famous Iron Curtain speech in Fulton, Missouri, a few days later. Ultimately the conspiracy theorists also have to ask themselves: if the US dropped the atom bomb on Japan as a means to strong-arm the Soviets why did Truman and his successors never attempt to threaten them with nuclear destruction in the four years to August 1949 when the Soviets developed their own atom bomb?

Another issue raised by the revisionists is whether Truman could have negotiated peace for less than unconditional surrender. It was Truman's intention to follow in Roosevelt's footsteps and demand an unconditional surrender from Japan – not an unreasonable stance given the overwhelming support for this policy from the American people in their determination that Japan should yield in the same way as Germany. Enforcement of Truman's tough terms made the use of the atom bomb essential. However, Truman was all too aware that to press for an unconditional surrender could be costly. Even 25,000 US deaths, the hypothetical casualty estimate put forward by the New Left historians, would have been hard to justify to an American audience with the knowledge that Truman had had the atom bomb but failed to use it.

However, by August 1945 Truman faced many more than 25,000 deaths in his armed forces. It lacks any credibility to believe that Truman was not fully informed of the extraordinary Japanese defences of the Pacific Island battles. After 1943, US statisticians would scour the aftermath of any major engagement. Reports would be written detailing not only the numbers of enemy dead, but also how they died in order to help weapons development and allocation. Senior generals in the field, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Stimson and of course the President were fully aware of the Japanese propensity to fight to the death. They were also cognizant that as the US approached nearer to Japan “real casualties were routinely outpacing estimates and the gap was widening”.Footnote33 It is therefore highly unlikely that Truman could have viewed Stimson's shocking projections for the invasion of Japan of between 400,000 and 800,000 US dead with anything other than trust.

As this article has explained in detail, the development of a death cult in the Japanese military and civil population made these predictions all too plausible. It is for this reason that Truman's administration considered and finally accepted a limited continuance of the Imperial system “in order”, as Stimson wrote in his diary, “to save us from scores of bloody Iwo Jimas and Okinawas”.Footnote34 In spite of the trenchant opposition of James Byrne, his Secretary of State, Truman too would come round to the ‘retentionist' view – hence the vagueness of Byrne's last offer to Hirohito's government, received in Tokyo after midnight on 12 August, which fudged the issue of conditionality by referring to a future Japanese government being established by “the freely expressed will of the Japanese people”. As this last phrase indicated, the implication was that Japan's constitutional arrangements could not stay as they were – for Truman's administration this was a ‘red line' issue. Nevertheless the President's step back from demanding unconditional surrender reflected Truman's fear of the casualty consequences of having to proceed with a conventional invasion of Japan. The lack of any response to Byrne's last message played on the nerves of the White House during 13 August.

Byrnes's message, which did not unequivocally demand unconditional surrender, implied that the Imperial system would be retained in some form. It is a measure of Japan's fanatical death cult that even this tempering of American demands for unconditional surrender provoked fury and a demand for outright rejection by General Korechika Anami, Japan's Minister of War, and General Yoshijiro Umezu, the Chief of the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff. After the dropping of two atom bombs and the invasion of Manchuria by the Soviet Union, Vice-Admiral Takijiro Onishi, the main architect of the kamikaze campaign, burst into a war council meeting to declare, “Let us formulate a plan for certain victory, obtain the Emperor's sanction, and throw ourselves into bringing the plan to realisation. If we are prepared to sacrifice 20,000,000 Japanese lives in a special attack effort, victory will be ours”.Footnote35

These were the men, not the ‘dove' faction, who ultimately controlled the fate of Japan's defence of its homeland. It should noted too that even the ‘dove' faction within the war council, which had initiated peace talks via Moscow, was adamant on the negotiation of a conditional surrender on terms that not only included the preservation of the Imperial system but also included an amnesty on war crimes and the refusal to accept an occupying army. The idea proposed by some revisionists that a surrender deal was on the table in August 1945 is very wide of the mark. Only the atom bomb injected a dose of realism into Japanese negotiations – and then only in the ‘dove' faction, which the Emperor eventually supported.

However, protestations of a fight to the death should not be taken with absolute certainty as to outcome, notwithstanding Japan's record. The Emperor might have called a halt to hostilities without the intercession of the atom bomb – he certainly had reasons to do so. Whether Japan would have surrendered before the launch of Operation Downfall remains a moot point. A post-war analysis by the United States Strategic Bombing Survey (USSBS) concluded that Japan would most likely have surrendered before 1 November.

It is a report that has been jumped on by the revisionists to give emphasis to their view that the use of atom bombs at the end of the Pacific War was unnecessary and immoral. Of course the USSBS was operating with the benefit of a hindsight that was not available to Truman. But even the USSBS could not be certain. ‘It seems clear', the USSBS concludes in its summary report, ‘that, even without the atomic bombing attacks, air supremacy over Japan could [my italics] have exerted sufficient pressure to bring about unconditional surrender.’Footnote36

This was no certainty. After all logic should have dictated that all hope of winning the war was lost at the Battle of the Philippine Sea in June 1944 with the annihilation of Japan's fleet carriers and their precious air crews. After the war Hirohito admitted in Show Tenno Dokuhaku Roku (The Emperor's Soliloquy) that he knew the war was lost even earlier, after the reverse at the Battles of the Kokoda Trail in New Guinea in November 1942. Thereafter the plan was to make American losses so painful that they would be forced to accommodate a peace with Japan – a plan for which Japan's state-sponsored death cult was an essential tool.

While the USSBS case presented a logical argument for Japan's surrender, it underestimated the unique psychological state of Japan's military and its people. In any case the USSBS report also pointed out that conventional bombing between August and November would probably have killed as many Japanese citizens as died at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Moreover the author of the report, Paul Nitze, a strong advocate of conventional bombing, was not exactly an impartial commentator on the persuasive power of the atom bomb. Contrary to the interpretation of the revisionists there is nothing in the USSBS report which suggests that Truman's decision to drop the atom bomb, as a means to end the war, was unreasonable given the information available to him at the beginning of August 1945.

With regard to uncertainties, it should further be noted that Truman and his commanders could have had no certainty that Japan would not develop its own nuclear weapon. Indeed Dr. Yoshio Nishina, who had worked with the legendary particle physicist Niels Bohr in Copenhagen, had started Japan's nuclear weapons programme at the Riken Institute before the United States’ inception of the Manhattan Project.

Indeed Truman's administration was well aware that Nishina's first large cyclotron had been purchased from the University of California, Berkekey, in 1939. From blueprints found this year at Kyoto University's Radioisotope Research Laboratory it is clear that Japanese scientists had designed a workable atom bomb. Another blueprint has also been found at Tokyo Keiki Inc., which reveals the blueprint of a design for a uranium centrifuge that was due to be completed on 19 August 1945. Japan simply lacked the resource elements such as yellowcake, uranium ore. It is needless to ask whether Japan would have used its own atom bomb. The answer is obvious.

Conclusion

The development of a brutal and ideological death cult within Japanese civilian and military society in the 1930s and 1940s made it extremely likely that there would be a fight to the death on the Japanese mainland in the event of an invasion by Allied forces.

Ultimately the dropping of atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki saved America and indeed Japan from this horrific prospect. Japan's Navy minister, Admiral Mitsumasa Yonai, went as far as to describe the US use of nuclear weapons as a blessing in disguise: “The atomic bombs and the Soviet entry into the war were, in a sense, gifts from God”Footnote37 because they gave Japan an excuse to surrender. As a war-ender the atom bomb worked. Upon Hirohito's surrender, apart from a few diehards, Japan's death cult ended – to be replaced, with surprising rapidity, with an almost equally entrenched pacifism.

The psychological aspects of Japan's death cult have been almost entirely ignored by the revisionist historians in their arguments that surrender would have happened before 1 November or would have quickly followed an invasion. Japan was a society in which its war minister, General Anami, at a post-atom bomb War Council meeting on 9 August, could suggest without appearing ridiculous, “Would it not be wondrous for the whole nation to be destroyed like a beautiful flower”.Footnote38 Similarly Baron Kiichiro Hiranuma argued, “Even if the entire nation is sacrificed to war, we must preserve the Kokutai [national polity] and the security of the Imperial Household”.Footnote39

Even if Truman knew nothing of such statements, or of the wider psychological background to Japan's defence of its home islands, he did understand the huge cost in life concomitant with an invasion of Japan. The overwhelming evidence of statistical analysis of Japanese military behaviour and its direct impact on casualties in the months preceding ‘the bomb' suggests that the revisionist view, that casualties for Operation Downfall would have been minimal, is hopelessly inaccurate. Their failure to substantiate their extraordinarily ‘low ball' casualty claims blows a hole in the already weak case that Truman's main goal in using nuclear weapons against Japan was atomic diplomacy.

Above all the revisionists ignore the practical realities and duties of political decision-making in an accountable democratic system. In truth the president, given his fiduciary duty to US citizens as the elected president of the United States, could not have justified not using the atom bomb.

Although in recent years a swathe of historians such as Robert James Maddox, Richard Frank, Sadao Asada and D.L. Giangreco have rebutted the revisionist case in some detail, the mythology of America's atomic diplomacy at the end of the Pacific War has persisted. Mythologies, like death cults, are difficult to put down.

However disappointing for the New Left revisionist historians and opponents of America's free market and geopolitical hegemony in the post-war world, sometimes the words of politicians have to be taken at face value. While Truman and his advisors were keenly aware of the geopolitical implications of the atom bomb, the overwhelming reason for using it was the obvious one, and was summed up by Secretary of War Stimson in Harper's magazine in 1947, when he simply stated,

the purpose [of the atom bomb] was to end the war in victory with the least possible cost in lives of the men in the armies which I had helped to raise. I believe that no man … could have failed to use it and afterwards have looked his countrymen in the face.Footnote40

It is rare to find single-factor explanations for major decisions – but the dropping of the atom bomb on Hiroshima may be the exception.

Notes

1. Robert James Maddox, Weapons for Victory: The Hiroshima Decision. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2004, p. xi.

2. Gar Alperovitz, Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb. New York: Alfred A. Knopf Inc., 1995, p. 341.

3. Kai Bird, New York Times, October 1994.

4. David Bergamini, Japan's Imperial Conspiracy, p. 17.

5. Mark Johnson, Fighting the Enemy; Australian Soldiers and their Adversairies in World War II. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000, p. 99.

6. Iris Chang, The Rape of Nanking, The Forgotten Holocaust of World War II. New York: Basic Books, 2011, p. 43.

7. Hal Gold, Unit 731. North Clarendon: Tuttle Publishing, 2007, p. 206.

8. Ibid., p. 42.

9. Ibid., p. 53.

10. Raden Dunbar, The Kavieng Massacre: A War Crime Revealed. Sally Milner Publishing, 2007.

11. R. Kowner (Ed.), The Impact of the Russo-Japanese War. Abingdon: Routledge, 2006, p. 148.

12. John Costello, Pacific War, 1941–1945. New York: Harper Perennial, p. 23.

13. Sir Ernest Satow, Letter to Frederick Victor Dickins & his Wife. Lulu.com, 2008.

14. Sven Saaler, and Victor Koschmann (Eds.), Between Pan-Asianism and Nationalism, Mitsukawa Kametaro and his campaign to reform Japan and liberate Asia. From Pan-Asianism in Modern Japanese History, colonialism, Regionalism, and Borders, p. 92.

15. Imperial Rescript to Soldiers and Sailors (Gunjin Chokyuyu)

16. Stephen S. Large, Emperor Hirohito and Show Japan. Abingdon: Routledge, 1998, p. xxxiv.

17. William B. Breuer, Retaking the Philippines, America's Return to Corregidor and Bataan: October 1944 – March 1945. New York: St.Martin's Press, 1986, p. 42.

18. Albert Axell, and Hideaki Kase, Kamikaze: Japan's Suicide Gods. New York: Longman, 2002, p. 145.

19. Ibid., p. 36.

20. Richard B. Frank, Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire. New York: Random House, 1999, p. 29.

21. David Pilling, Financial Times, 12 April 2008.

22. Bernard Millot, Divine Thunder: The Life and Death of the Kamikaze. Macdonald, 1971, p. 243.

23. Edwin Palmer Hoyt, The Last Kamikaze. Praeger, 1993. p. 210.

24. Allan R. Millett and Williamson Murray (Eds.), Military Effectiveness, Volume 3, The Second World War. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010, p. 37.

25. Ralph Raico, Harry Truman and the Atomic Bomb, excerpted from John Denson (Ed.), Harry S. Truman: Advancing the Revolution’ in Reassessing the Presidency: The Rise of the Executive State and the Decline of Freedom. Mises Institute, 24 November 2010.

26. Craig A. Carter, Rethinking Christ and Culture: A Post-Christendom Perspective. Brazos Press, 2007, p. 132.

27. Gerard Degroot, The Bomb: A Life. Random House, 2011, p. 80.

28. Bruce Cameron Reed, The History and Science of the Manhattan Project. Springer Science & Business Media, 2013, p. 379.

29. Maddox, Weapons for Victory, p. 101.

30. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, August 1985.

31. Harry S. Truman, and Robert H. Ferrell, Off the Record: The Private Papers of Harry S. Truman. University of Missouri Press, 1997, p. 35.

32. James Chace, Acheson: The Secretary of State Who Created the American World. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2008, p. 120.

33. D.M. Giangreco, Operation Downfall: The Devil was in the Detail. Autumn: JFQ, 1995, p. 87.

34. Robert S. Burrell, The Ghosts of Iwo Jima. Texas A&M University Press, 2011, p. 118.

35. Richard Frank, Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire. New York: Random House, 1999, p. 311.

36. United States Strategic Bombing Survey (USSBS) Summary.

37. Michael J. Hogan (Ed.), Hiroshima in History and Memory. Cambridge University Press, 1996, p. 106.

38. Robert J. Art, and Kenneth Neal Waltz, The Use of Force: Military Power and International Politics. Roman and Littlefield, 2004, p. 337.

39. Herbert Bix, Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan. New York: Harper Collins, 2001, p. 513.

40. Dennis Wainstock, The Decision to Drop the Atomic Bomb. Greenwood Publishing, 1996, p. 122.