ABSTRACT

Can law graduates contribute to the development of fair technology in a world where rapid technological innovation often outpaces societal considerations? This paper explores the gap between the skills required for a career in “responsible tech” and the skills taught in law and technology courses in the UK. It uses a literature review to identify four types of skills that are relevant for job applicants in this field: technological skills, legal knowledge, context awareness and soft skills. It then analyses 200 job advertisements from three “responsible tech” job boards to determine which skills are most in demand by employers. Finally, it discusses these findings in the light of the current state of law and technology education in the UK. The paper argues that there is a need for more alignment between law and technology curricula and the real-world needs of the “responsible tech” sector. It also suggests some ways to improve legal education in this area, such as interdisciplinary collaboration, experiential learning and critical thinking.

1. Introduction: the alignment problem and legal expertise

Most of us want a world where rapid technological development goes hand in hand with sufficient consideration of societal impacts of information technology. The idea of responsible technology comes from the multidisciplinary research tradition of responsible research and innovation (RRI) which was developed within EU research funding schemes to align research and innovation with societal values and expectations.Footnote1 The main aims of RRI have been the deepening of the relationship between science and society, through the active and systematic participation of citizens and civil society organisations (CSOs) in the design and creation of research, the accessibility of scientific knowledge, the promotion of science education and the protection of ethical values and gender equality.Footnote2 Especially in the case of information technologies and AI, where breakthroughs often outpace societal understandings of technology, the need for responsible technology becomes even more salient.

While software developers have moral responsibilities arising from their professional identity,Footnote3 one of the main hopes our societies have for holding technology developers accountable and contributing to the development of responsible technology lies with law graduates. Law graduates are vital in ensuring responsible technology development because they possess the expertise to interpret and apply the law, uphold ethical standards, influence policy, enforce regulations, and educate others about the legal implications of technology.Footnote4 To what extent, however, is this hope realistic? “Law and technology” modules are mushrooming in law curricula in the United Kingdom. As section 5 of this article shows, the reference to “law and technology” modules encompasses a variety of modules covering such legal fields as data protection, intellectual property and privacy and human rights law; the common denominator is the dialectic relationship between law and technology as the underpinning of the issues covered in modules like these. Most law faculties offer it as an elective module for undergraduate students, whereas an increasing number of law schools create bespoke master’s courses, often in collaboration with computer science faculties of their university.

There are several value propositions for studying a law and technology course, at either undergraduate or postgraduate level. One significant advantage is that students will have the chance to learn about incorporating legal safeguards into the development of advanced technology. As legal academics, we insist that legal education should equip students with the necessary skills to “question the proliferation of technological applications to ensure they are developed for the public good”.Footnote5 In educational reality, though, discussions shift to the “instrumental” value of legal education, ie the extent to which legal courses enable students to achieve a specific employment objective.Footnote6 Previous studies have shown that “employability enhancement” is becoming a “threshold standard” for evaluating the quality of legal education, both from the perspective of students and from that of employers.Footnote7

Much ink has been spilled over the implications of technological evolution for the legal profession and the role of legal education in preparing students for these implications.Footnote8 Scholars have shown how automating certain aspects of the job of lawyer necessitates preparation on behalf of law students that goes beyond substantive legal knowledge.Footnote9 Yet a career in the legal profession is far from the only employment path for law graduates. In fact, a large proportion of UK law graduates pursue alternative employment pathways, including academia, the civil service or third sector bodies, like charities and NGOs.Footnote10

In the case of students who have specialised in “law and technology”, an increasingly upcoming employment pathway is the so-called “responsible tech” field. Broadly speaking, the “responsible tech” field revolves around the so-called alignment problem,Footnote11 ie the challenge of building powerful technologies, including artificial intelligence systems, that are aligned with the values and goals of their designers and operators. Proceeding from the observation that technologies like AI produce unintended or harmful outcomes, such as bias, discrimination, manipulation or deception, organisations in the “responsible technology” field seek to address these risks and ensure that technologies are trustworthy, fair and socially beneficial. In jobs related to “responsible tech”, legal professionals are expected to either perform research or advocacy tasks related to technological development or actively participate in the design and development of technologies as part of a multidisciplinary team. Hence, in this field, legal experts can, in theory, work not only for consultancy companies or advocacy organisations, but also for cutting-edge technology developers like OpenAI or DeepMind and shape the future of technology in a positive manner. Does legal education, however, truly prepare students for a role in “responsible tech” in the real world?

This paper seeks to provide an answer to this question by proceeding in four steps. First, it explains why it is important to consider the impact of law and technology education on the employment of law graduates in the twenty-first century, either in the responsible technology job market, or in the legal job market. Second, the article draws on the literature on law and technology education to construct a typology of the skills needed to pursue a career in “responsible tech” as a legal expert. Third, it analyses 200 job advertisements from three major “responsible tech” job boards to identify which of the theoretically relevant skills are more salient in the real-world job market. Fourth, it reflects on the state of play in contemporary “law and technology” curricula in the UK and the extent to which the required skills are effectively being cultivated. While the UK is used here as an example, the findings of this analysis might be of relevance to legal education in other countries. In conclusion, reflections are offered about the need for further research into the main impediments in equipping law graduates with skills that would be more enabling for them in pursuing a “responsible tech” career path without denying the critical character of legal expertise in keeping technology accountable.

2. Preparing law graduates for the 21st century

From the perspective of law schools, and beyond the important societal role of law graduates as stewards of responsible technology,Footnote12 there are three distinct motivations behind offering fundamental technological literacy to law graduates: preparing them for a career in the responsible technology job market, preparing them for a career in other markets and preparing them for the twenty-first century more broadly.

Regarding the interest of current and future students in responsible technology, it is indicative that recent UCAS data demonstrate an increasing interest of students in technological subjects.Footnote13 More specifically, computer science courses have climbed up to almost 50% from 2011 to 2020 according to Interest of Students, whereas students increasingly demand a connection with AI in other courses including law.Footnote14 In the responsible technology job market, there’s a growing demand for legal professionals who understand emerging technologies and their implications. This expertise is essential for roles not only in law firms, corporate legal departments and legal start-ups,Footnote15 but also in technology development companies,Footnote16 creating diverse career opportunities.

Beyond pursuing a career in the responsible technology sector, law graduates will benefit significantly from technological literacy in an ever-changing and technologically infused legal job market. Susskind argues that technology will not only automate routine tasks but also enable new ways of delivering legal services, arguing that lawyers need to adapt by acquiring new skills and embracing new ways of working, including increased reliance on artificial intelligence and online legal services.Footnote17 Currently, law students use IT extensively but ineffectively, fail to transfer skills, and lack fluency with the electronic sources now common in practice.Footnote18 They often overestimate their information literacy and take passive approaches to acquiring information.Footnote19 While law schools have been slow to incorporate new technologies like AI,Footnote20 the pace of innovation necessitates changes, including effective instruction in reading and analysis, use of advanced online tools and selection of appropriate online resources.Footnote21

Apart from employability concerns, all law students should understand the relationship between law and technology to uphold their societal and ethical responsibilities in the twenty-first century. For example, as technology becomes integral to legal practice, lawyers must understand its implications to uphold ethical standards.Footnote22 This includes issues like data privacy, cybersecurity and the ethical use of AI in legal decisions. Furthermore, technologically literate law graduates can educate the publicFootnote23 about their digital rights and the legal implications of technology use, promoting informed citizenship in a digital society.

3. Constructing the “alignment expert”: a typology

While it is common ground that “new legal roles” will be created in response to technological transformation,Footnote24 there are different accounts as to what these roles will look like and to what extent legal expertise will contribute to them. Bullows, drawing on Susskind,Footnote25 focuses on business- and technology-oriented legal roles, such as the “legal technologist” (“an intermediary between technology and law”), the “legal data scientist” (who “manipulates data for use in systems and processes”) and the “legal process analyst” (who “analyses and renovates the organisation of law firms”).Footnote26 Volini argues in favour of a “robust tech curriculum” for law students, involving “concepts of networking and programming” to allow law graduates to acquire a deep understanding of IT instead of “solely user-side tech education”.Footnote27 On the other hand, Barczentewicz calls for a more granular approach that connects the acquisition of skills with the “direct need for such skills and knowledge in students’ future careers”.Footnote28 Advanced technological knowledge, in his view, is only necessary for a minority of current law students, as for most future legal professionals “proficiency in effective uses of office and legal research software and standard means of online communication and basic cybersecurity” will suffice.Footnote29

Janeček, Williams and Keep offer a conceptualisation of skills that is critically relevant for the purposes of the present paper. They reflect on their experience of designing and delivering a course in “Law and Computer Science”, where students from both disciplines had to engage in “multidisciplinary teamwork, in-depth discussion and dialogue between law and computer science” (emphasis added).Footnote30 As mentioned in the introduction, this is very much a requirement in “responsible tech” jobs, where legal experts are expected to either conduct research or advocacy tasks related to technological development or contribute to the actual work of designing and developing technologies as part of a multidisciplinary team.Footnote31

Especially in the latter case, it is crucial that the “alignment expert” collaborates effectively with engineers and system designers, with a view to embedding legal and ethical safeguards in the technology, much like the aims of the responsible research and innovation (RRI) tradition within EU research funding schemes.Footnote32 Five key skills are singled out by Janeček, Williams and Keep: (1) “mindset understanding”, ie understanding the strengths and limitations of the computer science mindset; (2) “data-oriented thinking”, ie understanding and being able to design knowledge management systems and databases; (3) “agile systems and design thinking”, ie the capacity to abstract problems so that they are solvable by technologies; (4) “commercial awareness”, which is appreciating the client’s interests and the existence of limitations for any potential solution; and (5) “digital ethics and the law of AI and digital technology”, ie substantive knowledge about legal issues applicable to new technologies such as data protection, liability for software, etc.

As Janeček, Williams and Keep note, one of the main limitations in understanding the depth of these needs, as well as in realising them, stems from the fact that “one cannot train for a role that does not yet exist”.Footnote33 Some progress has undoubtedly been made in the last two years and one increasingly sees roles such as “legal engineer” or “legal designer” within law firms.Footnote34 Nonetheless, the “responsible tech” field offers many examples where alignment experts need to possess the skills articulated in the literature about “legal technologists”. For example, a researcher in AI alignment needs to possess “foundational understanding of how large pretrained models (e.g. large language models) represent and manipulate concepts and world knowledge”,Footnote35 which is quite advanced technological knowledge in natural language processing and AI. A researcher in AI governance and forecasting often has a background in “economics, machine learning or engineering”.Footnote36 Softer skills, such as agile thinking and mindset understanding, are greatly appreciated too, as companies often vouch to hire “regardless of background and credentials”Footnote37 and the capacity to collaborate with multiple research teams is often seen as an advantage, although in some cases this is not reflected in the application tests requiring advanced quantitative knowledge and understanding of advanced mathematics.

Considering this need to collaborate with multidisciplinary research teams and aiming to bring the insights of this literature together, it seems that law graduates interested in pursuing a career in “responsible tech” shall measure their skillset against the following core competences: (a) “technological literacy”, further broken down in basic technological skills, data systems knowledge, programming knowledge and advanced specialised technological knowledge such as deep understanding of AI, machine learning (ML) or cybersecurity; (b) “substantive legal knowledge” about the policy and legal implications of AI and digital technologies, covering such fields as data protection or IP regulation; (c) “context awareness”, not being confined to commercial priorities but extending to knowledge of subject matter or the dynamics of a specific social and organisational field eg medicine and health data usage or national security; and (d) “soft skills” such as mindset understanding and design thinking, not measured by qualifications or credentials, but exemplified through previous experience and the cultivation of relevant skills in education. One might argue that a combination of all these skills is essential for a candidate’s performance in the field; however, the relative importance of each skill may vary depending on the specific role. This raises the question: how significant are those competences compared to one another? To what extent does current legal education in the UK prepare law students for a career in the “responsible tech” field? Section 4 addresses the first question, before section 5 addresses the second one.

4. Core competences of the “alignment expert” in the real world: analysing job advertisements

4.1. Methodology

For the purposes of this paper, 200 job advertisements were extracted and analysed from three major databases for “responsible tech” jobs: alltechishuman, 80,000 hours and digital rights community.Footnote38 These job advertisements were posted online between September 2022 and February 2023 and include job opportunities in various countries, mostly around the alignment of AI and other cutting-edge digital technologies. The advertisements were chosen in the following manner: all advertisements were given a unique number and then a randomiser application was used to select the 200 ones that would be analysed for this paper.Footnote39

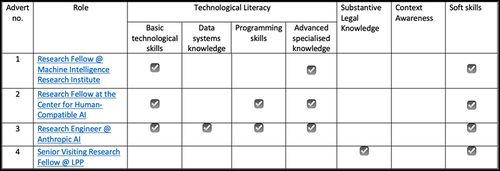

In the first instance, content analysis was undertaken to assess whether advertisements required the skills reflected in the previously described core competences of the alignment expert.Footnote40 This involved manual coding of the advertisements through NVivo12 under the core competences as nodes, interpreting eg whether a particular wording like “ability to handle ambiguity” refers to soft skills or to the awareness of a specific context that is inherently uncertain and ambiguous. The analysis yielded a categorisation of the job advertisements presented in the following .

This content analysis was mostly quantitative seeking to extract objective content from the advertisements,Footnote41 such as the mention of a particular legal degree as a proxy for the requirement of substantive legal knowledge in a particular job advert. In some cases, however, this was not possible, as certain job requirements did not clearly match the language of job adverts but were rather inferred from the interpretation of such adverts. In these cases, content analysis was more qualitative, seeking to uncover the meaning of job adverts, performing open coding on the adverts and then organising the categories under higher-order headings that correspond to a requirement already identified under the previously analysed typology.Footnote42 Specific examples of performing the content analysis are provided in the following subsection.

Following this stage, the work involved calculating a ratio or percentage of job advertisements that require a certain skill or background, with a view to comparing a part of the group to the whole group, as well as comparing two parts of the group. For example, 54 jobs required substantive legal knowledge compared to 128 jobs which required soft skills, making the ratio of job advertisements that require knowledge of the law to job advertisements that require soft skills 54/128 = 0.42. Visualisations are used in the following sections to highlight key findings and compare different categories or groups.

4.2. Interpreting the required skills

In some cases, the association between a required skill and the wording of a job advert would be straightforward. When it comes to programming skills, for example, job advertisements would refer to specific programming language that the applicant should be proficient in, such as JavaScript,Footnote43 Python,Footnote44 SQL,Footnote45 SwiftFootnote46 or R.Footnote47 In other cases, job advertisements might not be as specific as requiring a specific programming language, but mention more broadly that the successful applicant will have programming knowledge, ie they will be able to understand the languages, frameworks and architecture that enable them to create a digital product and provide computers with instructions on what actions to perform.Footnote48 Similarly, the knowledge of data systems is associated in job advertisements with knowledge of and experience in using specific well-known database technologies like Spark,Footnote49 a multi-language engine for executing data engineering, data science and machine learning on single-node machines or clusters, or data warehouses, ie systems that aggregate data from different sources into a single, central, consistent data store to support data analysis, data mining and artificial intelligence,Footnote50 like Snowflake, Redshift or BigQuery.Footnote51 In other cases, data systems knowledge is inferred by reference to experience “curating” or “improving” large datasets,Footnote52 or the ability to “conduct in-depth evaluation of data and present new solutions”.Footnote53

Substantive legal knowledge was another skill that was often straightforward to identify in the job advertisements. A main indicator is the requirement that the applicant has deep knowledge of specific legislative instruments such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR),Footnote54 the UK Data Protection Act 2018,Footnote55 the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA)Footnote56 and the Privacy and Electronic Communications (EC Directive) Regulations 2003 (PECR),Footnote57 as certified by relevant qualifications provided by associations of professionals like Certified Information Privacy Professional (CIPP),Footnote58 the International Association of Privacy Professionals. Interestingly, academic qualifications in law are in most cases not strictly required. Another main indicator of substantive legal knowledge is the work experience demonstrating “in-depth knowledge and applied understanding of the area of expertise”,Footnote59 or experience in conducting specific legal tasks such as “developing and implementing privacy compliance programs”.Footnote60

Other skills required more interpretation of the job advertisements. To distinguish, for instance, between “basic technological skills” and “advanced specialised knowledge”, one must become more familiar with the state of the art in a specific technological domain and seek to understand what is considered a baseline skill compared to more sophisticated technological capabilities. A helpful indicator is the use of specialised technological tools that require advanced knowledge, such as distributed event processing systems like Kafka, or configuration management and orchestration tools like Kubernetes.Footnote61 Basic technological skills, in contrast, are often associated with capacities like “attention to technical detail” or broader experience using technologies related to law such as document automation.Footnote62 Advanced specialised knowledge is also often required in more senior positions,Footnote63 whereas basic technological skills may be required in entry-level jobs.Footnote64

The two skillsets that arguably required the widest interpretative construction were “soft skills” and “context awareness”. Increasingly becoming a buzzword for the twenty-first century job market,Footnote65 soft skills are attributes that facilitate effective and harmonious interaction between people. Some examples of soft skills are critical thinking, problem solving, public speaking, professional writing, teamwork, digital literacy, leadership, professional attitude, work ethic and intercultural fluency.Footnote66 To identify the requirement for soft skills in the advertisements, there was a need to read the advert as a whole, rather than seek to code for specific phrases, to understand the extent to which the role emphasised the requirement for skills contributing to effective teamwork, managing or collaborating with other individuals, and generally skills that are acquired not strictly via formal qualifications but more via informal education and work experience. Advertisements referred to soft skills when requiring a “problem solving mindset”, “business acumen” and “building coalitions” capabilities,Footnote67 the desire to “develop trusted relationships”Footnote68 or “good communication skills”.Footnote69

“Context awareness”, referring to knowledge and deep understanding of a specific field or activity, also required a holistic reading of the advertisements. In some cases, advertisements would make it clear that they need such knowledge, eg the applicant should have regulatory experience in “biopharmaceuticals”,Footnote70 experience in “disability rights” advocacy,Footnote71 understanding of “key developments and debates related to Internet Freedom”Footnote72 or “experience working in newsrooms”.Footnote73 In other cases, the same requirement would be less explicit and ascertained via the analysis of references to other skills. For example, the requirement for an applicant to have experience in “compliance working in a tech company” is indicative of the need to understand well the specific context of tech social media companies and how a compliance officer operates in them.Footnote74

4.3. Presenting the findings

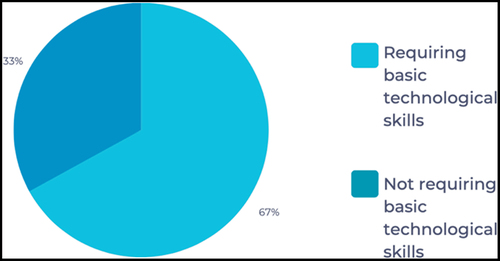

“Basic technological skills” was the most popular skillset for a career in the responsible tech market. As the following shows, 134 of the 200 (67%) extracted job advertisements required that the applicant possesses some fundamental technological skills.

The second most popular skillset as identified in the job advertisements were, interestingly, soft skills: 128 of the 200 (64%) job advertisements required some type of soft skill as a required capacity of the successful applicant: as shown in the following .

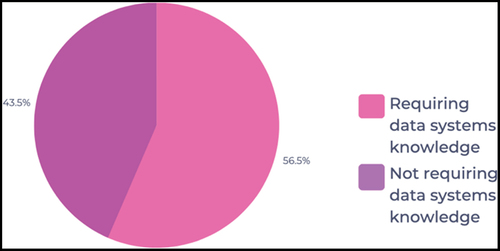

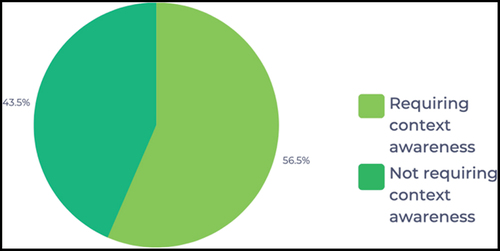

Quite popular were also two other types of skillsets: data systems knowledge and context awareness. In both cases, 113 of the 200 (56.5%) job advertisements required the applicants to demonstrate that they possess the skills in question as shown in the following .

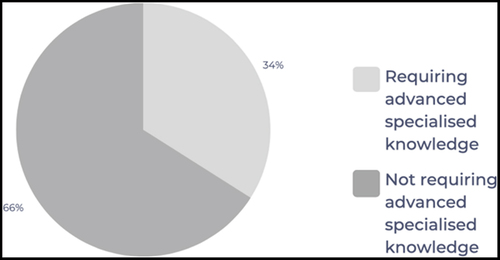

Coming to the less represented skills in the dataset, a requirement for advanced specialised technological knowledge is seemingly less widespread in the responsible tech market, allaying the fears of scholars who think that the future of technology will be primarily shaped by technical experts working in niche areas.Footnote75 Sixty-eight out of the 200 (34%) job advertisements required advanced specialised technical knowledge from the applicant as shown in the following .

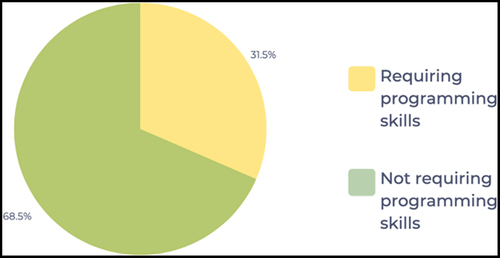

The picture regarding programming skills is similar. Sixty-three out of the 200 (31.5%) job advertisements deemed such skills as required for the advertised job as shown in the following .

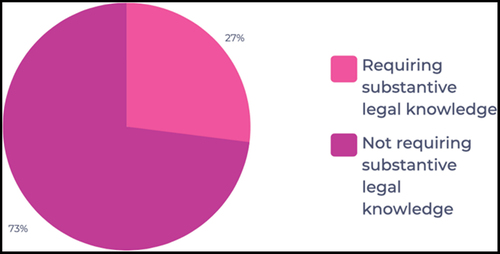

Finally, yet very interestingly, only 54 out of the 200 job advertisements (27%) required substantive legal knowledge as shown in the following .

4.4. Discussion

Admittedly, the responsible tech job market is not a unified market, but rather a diverse and growing field of different roles, sectors, skills and expertise that aim to build a better tech future.Footnote76 Within this heterogeneous job market, it may not come as a surprise that breadth is rewarded more than depth: a minimum threshold of technological literacy is often required (in 67% of the cases in the present sample), but then it is more a matter of all-round capabilities and familiarity with commonly used data systems and the context in which the work takes place, as reflected respectively in the percentages of jobs requiring soft skills (64%), data systems knowledge (56.5%) and context awareness (56.5%). Working across disciplinary boundaries often provides these skills. This does not mean, of course, that more traditional disciplinary experts will not be able to find a job in the sector, but cases where deep expert knowledge is required, either technical or legal, belong to the minority of the present sample. This is exemplified by the percentages of the jobs requiring substantive legal knowledge (27%), programming skills (31.5%) or advanced specialised technical knowledge (34%).

While basic technological literacy and knowledge of some data systems might be expected based on the nature of the responsible tech market, the significance of soft skills and context awareness is intriguing. Yet these findings are consistent with the theoretical claim that soft skills are essential in today’s economy,Footnote77 and might even weigh more in the hiring process compared to hard skills. They are also consistent with the claim that there needs to be more investment in education and training systems, especially in lifelong learning, digital literacy and socio-emotional skills.Footnote78 In fact, according to a survey by LinkedIn, 92% of hiring managers said that soft skills are more important than hard skills.Footnote79 Soft skills are essential for any job that involves working with others, whether as colleagues, customers, clients or stakeholders. They help people to communicate effectively, collaborate productively, adapt to changing circumstances, resolve conflicts peacefully and lead by example.Footnote80 In that sense, it should be expected that they would be highly desirable in a job market where experts are expected to collaborate with experts from different disciplines to contribute towards the alignment of technology with fundamental ethical, societal and legal values. The characteristics of the “responsible tech” job market also explain the significance of context awareness, as exemplified by the percentage of jobs requiring it (56.5%). Jobs in this market reflect the complexity and multitude of technologies, often mirroring their rapid development (for example, there has been a boom in jobs requiring expertise in transformer models following the success of ChatGPT).Footnote81 Awareness of the specific context of the sector or the field within which the job is located promises familiarity with the specific requirements of the job and a higher aptitude for learning quickly how to address its challenges.

On the other hand, specialised expert knowledge, either legal or technological, is required for several job opportunities, but these only represent roughly one-third of the whole market (27% in the case of legal expertise, 31.5% for programming skills and 34% for advanced technical knowledge). In “The Future of the Professions”, Susskind and Susskind argue that technology will enable new ways of delivering professional services that are more affordable, accessible and efficient than the traditional models based on human experts.Footnote82 However, the present findings indicate that human expertise is only part of the picture, rather than the whole picture in the responsible technology job market. Other traits like soft skills or context awareness are also important and valuable. They can help professionals to communicate effectively, collaborate with others, adapt to changing situations and understand the needs and expectations of different stakeholders. These skills are not easily replicated by technology and may even become more in demand as technology advances. Especially thinking about legal expertise, reliance on it confines an applicant to public interest advocacy roles, or adviser roles on aspects of technology law, as well as in-house support at tech innovation companies on specific areas such as intellectual property, contracts, licensing or litigation.Footnote83 Roles that are more hands-on and directly relevant to designing and developing system architectures, such as legal engineer, legal knowledge engineer or legal technologist, by contrast, do not require legal expertise.Footnote84

Hence, it is neither the case that legal education can rely on its traditional subject matter and methods, nor that it must achieve the impossible by turning law graduates into advanced technological experts and programmers, if it is to empower graduates to have a competitive advantage in the responsible technology job market. What are UK law schools currently doing and what should they be doing in this respect?

5. UK law and technology education: state of play and the way forward

A few caveats should be registered before embarking on the assessment of the offered knowledge and skills in UK law and technology education. First, considering that the author is, at the time of writing, the Programme Director of a postgraduate degree in law and technology at Keele University,Footnote85 it would not be appropriate for this paper to compare in depth the approach of specific UK universities in delivering law and technology education. Rather, this section will mostly present the broader state of play and make some recommendations to achieve more alignment between law and technology curricula and the real-world needs of the “responsible tech” sector. Second, it is acknowledged that a deeper evaluation of the knowledge and skills offered by law and technology modules would require further large-scale empirical research, potentially including the surveying of views of students who have studied these modules across different UK law schools, as well as quantitative data on the subsequent employment of law graduates who studied the modules. The present analysis, which is based on publicly available information about the stated purpose and teaching aims of the modules, seeks to demonstrate the importance of such further empirical research. Following from this analysis, it will be argued that such areas as interdisciplinary collaboration, experiential learning and the cultivation of critical thinking should be seen as priorities for law schools interested in equipping their graduates with much-needed skills for the responsible technology job market.

Law and technology education in UK law schools is a broad church. There are many universities offering undergraduate courses in law and technology, either as elective options, or, more exceptionally, as core parts of the curriculum.Footnote86 In the first category, modules cover a very wide selection of choices:

Personal information lawFootnote87

Information technology and the lawFootnote88

Internet law and policyFootnote89

Robotics and the lawFootnote90

Intellectual property lawFootnote91

CyberlawFootnote92

CybercrimeFootnote93

Law, science and technologyFootnote94

Law and new technologiesFootnote95

Privacy, data protection and cybersecurity lawFootnote96

Privacy, surveillance and the law of social mediaFootnote97

The regulation of platform capitalismFootnote98

Law, money and technologyFootnote99

Law, technology and innovationFootnote100

Artificial intelligence and the future of legal servicesFootnote101

Artificial intelligence and the lawFootnote102

Technology, criminal justice and human rightsFootnote103

Data law and governance.Footnote104

Most UK law schools are also offering dedicated postgraduate programmes on law and technology:

The Oxford LawTech Education ProgrammeFootnote105

The LLM in Law and Technology by King’s College, LondonFootnote106 Queen’s University BelfastFootnote107 and the University of WestminsterFootnote108

The LLM in Innovation, Technology and the Law by the University of EdinburghFootnote109

The LLM in Law, Innovation and Technology by the University of BristolFootnote110

The MSc/LLM in Law, Artificial Intelligence, and New Technologies at Keele UniversityFootnote111

The Technology, Media and Telecommunications Law LLM at QMULFootnote112

The Law and LegalTech LLM at the University of Portsmouth

The LLM Law, Technology and Innovation at the University of South WalesFootnote113

The Emerging Technologies and the Law LLM at Newcastle UniversityFootnote114

The Information Technology and Intellectual Property Law LLM at the University of SussexFootnote115

The Cyber Law LLM at the University of NorthumbriaFootnote116

The LegalTech and Commercial Law LLM at Swansea UniversityFootnote117

The International Commercial and Technology Law LLM at the University of ManchesterFootnote118

The Corporate Law, Computing and Innovation LLM/MSc at Ulster UniversityFootnote119

The Technology Law LLM by Nottingham Trent University.Footnote120

In most cases, it seems that the main aim of both undergraduate and postgraduate courses in law and technology is to provide substantive legal knowledge, covering various legal fields related to technology, such as data protection, intellectual property law, or privacy and human rights. Assessment methods often reflect those in traditional legal education: essays, research papers or written examinations. There might be some exceptions to that, particularly at postgraduate level. Notably, the researchers behind the Oxford Law and Computer Science course have actively considered the skills gaps that currently exist in legal education in respect of AI and digital technologies.Footnote121 This programme has been explicitly designed to help students from both law and computer science to collaborate more effectively. Through assessing students by reference to their participation in interdisciplinary group projects, the programme arguably facilitates the cultivation of both soft skills and basic technological literacy for law graduates. Other postgraduate programmes, such as the ones offered by Keele, Portsmouth and Ulster,Footnote122 seek to combine legal with computing science knowledge, enabling or mandating their students to study such modules as system design and programming, software engineering and visualisation for data analytics. These programmes may have the promise of cultivating technology-related skills for their graduates, which, as we have seen, may be particularly crucial for work opportunities in the responsible technology job market. Finally, programmes such as the one offered by Swansea,Footnote123 with its emphasis on applied legal tech skills, can improve the context awareness of graduates about the legal tech sector and help them familiarise themselves with the requirements in relevant jobs. Other law schools also offer similar modules about the use of digital technology in legal practice like Bristol,Footnote124 or modules cultivating technological literacy like Edinburgh,Footnote125 to facilitate the uptake of much needed skills for the market.

The present analysis is far from exhaustive, and it would be an oversimplification to say that UK law schools only impart substantive legal knowledge to their graduates. Yet, proceeding from the findings of this study it is suggested that there are more steps to be taken to align better the skillsets of law graduates with the needs and requirements of the “responsible technology” sector. Interdisciplinary approaches to law and technology education, involving the participation of computer science experts in the design and delivery of curricula, hold great promise both for cultivating soft skills and for improving the technological literacy of law graduates. Interdisciplinary collaboration promotes open-mindedness and the ability to draw insights from diverse disciplines and apply them to the area of focus at hand, increasing creativity and bolstering innovation.Footnote126 Being involved in collaborative projects with computer science students, law graduates will have to use information rooted in a range of perspectives, thus challenging their pre-existing ideas, and becoming better at identifying bias in themselves and others.Footnote127 In this process, they will also improve their communication skills, as they will have to adjust their knowledge to meet the needs of a very different audience, computer science experts, and collaborate effectively with them. Although it is not likely that law graduates will be able to acquire advanced specialised knowledge and become expert programmers and software engineers after a course offered by a law school, the present analysis has demonstrated that for most opportunities in the job market, that is not necessary. Given that 67% of the advertisements required basic technological skills as opposed to 31.5% of the advertisements requiring programming skills, it follows that the acquisition of basic technological skills can yield significant results in improving employment possibilities. This is consistent with findings in the secondary literature that the acquisition of IT skills improves both employability chances and employment conditions (eg pay) in other job markets.Footnote128

Beyond soft skills and technological literacy, the previously presented findings indicate that context awareness, ie knowledge and deep understanding of a specific field or activity, is very much sought after in the marketplace. From a legal education perspective, experiential learning, ie education that involves learning by doing, would be one of the main delivery methods to enhance context awareness. Already employed in many UK law schools,Footnote129 experiential learning can benefit law students by enhancing their skills, such as client interviewing, communication, advocacy, research and writing, negotiation, presentation, coordination, organisation, public speaking and teamwork.Footnote130 It can include activities such as hands-on legal advice, internships or study abroad experiences. While there are many opportunities for law students to develop soft skills and context awareness through participating in clinical legal education modules in most UK law schools, such modules are, in most cases,Footnote131 optional and are not tailored to the needs of the specific context of law and technology.Footnote132 For the purposes of law and technology education, experiential learning could involve both initiatives within the organisational confines of the law school, eg legal advice clinics to develop skills and knowledge in a real-world setting, and initiatives such as placements that would provide law graduates with very valuable work experience in specific technology-related work environments. Experiential learning would also boost soft skills, as it provides students with the opportunity to take the initiative, make decisions, and be accountable for the results of their performance, thus making them better team players and managers of people.Footnote133

At the same time, and while not explicitly regarded as a required skill, more emphasis on critical thinking is likely to enhance the employment opportunities of law graduates in the responsible technology sector. Critical legal thinking is required to resist the pressure legal experts face in this job market, as also demonstrated by the findings of the present study. Through such thinking, the significance of the legal expert in designing and deploying responsible technologies can be reaffirmed. In a complex and dynamic environment like cutting-edge technology development, possessing a critical and deep understanding of the law and its underlying principles, rather than just memorising rules and cases, promises to be pivotal in mitigating risks and harms caused by technology for society and the environment. Without critical legal thinking, communication with diverse stakeholders, including technology developers, will drift between rubberstamping and scaremongering. Legal education in the UK already values critical thinking highly, with some law schools even priding themselves in taking a critical approach to the study of law.Footnote134 It is important that this is reflected in the area of law and technology education, aiming for bigger picture critiques of law and technology intersections, rather than emphasising the study of specific legal provisions or landmark cases, decolonising the curriculum which is often influenced by the predominant “whiteness” of AI and other technologies,Footnote135 and assessing students for their capacity to think critically rather than process a vast amount of information – the latter is, either way, nowadays a job for AI. In other words, we need law and technology modules that better incorporate critical thinking. Furthermore, such modules would significantly benefit from also incorporating technology ethics within their curricula, since ethics would provide significant insights into the context of responsible technology and would both equip graduates with invaluable skills and help them uphold their societal role as stewards of responsible technology.Footnote136

6. Conclusion

This paper has explored the role of legal education in preparing law graduates for a career in the “responsible tech” field. As cutting-edge technology generates numerous social and economic impacts, embedding legal protections in technology development becomes of increasing significance. The paper has highlighted the skills needed for law graduates to contribute to the development of fair technology: technological literacy, legal knowledge, context awareness and soft skills. The analysis of job advertisements from three major “responsible tech” job boards has revealed that the most salient skills in the real-world job market are not always the ones that are cultivated by contemporary “law and technology” curricula in the UK, although some steps are certainly taken in this direction by UK law schools.

These findings raise questions about the future of legal education and the process of equipping law graduates with skills that would be more enabling for them in pursuing a “responsible tech” career path. Further research could, for example, seek to shed light on the dynamics of collaboration between law schools and computer science faculties to provide law students with interdisciplinary training that covers not only legal principles but also technical knowledge. How are incentives and appetites to proceed with such collaborations created and maintained within UK universities? What kind of organisational commitments and leadership drives are needed to establish meaningful collaborations of this type? Another very interesting project could bring to the forefront the perspective of recruiters in the responsible tech market. Would they agree with the interpretation of job advertisements made in the present study? What kinds of skills would they prioritise when considering a law graduate for a job in their sector? By reference to which benchmark or indicator do they evaluate the extent to which an applicant possesses a required skill?

This is not to say that the only value of a legal education is the “instrumental” value of legal courses in enhancing employability of law graduates. While employability is an important consideration, it should not come at the expense of preparing students to be critical thinkers and ethical decision-makers in the face of rapid technological change. Nonetheless, without the necessary skills to work in the responsible technology market, future legal experts will not be able to question the proliferation of technological applications to ensure they are developed for the public good. This paper has shed light on the complex relationship between legal education and the “responsible tech” field. While legal expertise has the potential to play a crucial role in shaping the future of technology in a positive manner, more needs to be done to ensure that law graduates are equipped with the skills that are most relevant to the real-world job market. As technology continues to evolve at a rapid pace, it is imperative that legal education keeps up and prepares students for the challenges and opportunities of the twenty-first century.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 Stevienna de Saille, “Innovating Innovation Policy: The Emergence of ‘Responsible Research and Innovation’” (2015) 2 Journal of Responsible Innovation 152.

2 Richard Owen, René von Schomberg and Phil Macnaghten, “An Unfinished Journey? Reflections on a Decade of Responsible Research and Innovation” (2021) 8 Journal of Responsible Innovation 217.

3 Coleen Greer and Marty Wolf, “Overcoming Barriers to Including Ethics and Social Responsibility in Computing Courses” in Mario Arias-Oliva and others (eds), Societal Challenges in the Smart Society (Universidad de la Rioja 2020) 131–44.

4 Kristen Murray, ”Take Note: Teaching Law Students to Be Responsible Stewards of Technology” (2021) 70 Cath UL Rev 201.

5 Francine Ryan, “Rage Against the Machine? Incorporating Legal Tech into Legal Education” (2021) 55 The Law Teacher 392, 402.

6 Alex Nicholson, “The Value of a Law Degree – Part 4: A Perspective from Employers” (2022) 56 The Law Teacher 171.

7 ibid 174; Siobhan McConnell, “A Systematic Review of Commercial Awareness in the Context of the Employability of Law Students” (2022) 3 European Journal of Legal Education 127.

8 Emily Janoski-Haehlen, “Robots, Blockchain, ESI, Oh My!: Why Law Schools Are (or Should Be) Teaching Legal Technology” (2019) 38 Legal Reference Services Quarterly 77; Cemile Cakir, “A Master’s Degree: Empowering Digital-Age Lawyers in Legal Technology” in Ann Thanaraj and Kris Gledhill (eds), Teaching Legal Education in the Digital Age (Routledge 2022) 164–79; Marcus Smith, “Integrating Technology in Contemporary Legal Education” (2020) 54 The Law Teacher 209.

9 Nicholson (n 6) 171.

10 Amy Bullows, “How Technology Is Changing the Legal Sector” (2021) 55 The Law Teacher 258.

11 Brian Christian, The Alignment Problem: How Can Machines Learn Human Values? (Atlantic Books 2021).

12 Murray (n 4).

13 AHZ, “Growing Interest of Students in Technological Subjects” <https://ahzassociates.co.uk/interest-of-students-in-technological-subjects/> (accessed 24 April 2024).

14 ibid.

15 Seb Murray, “As the Legal Industry Undergoes a Digital Transformation, These Specialized Programs Have Emerged as an Increasingly Relevant Educational Pathway” (LLM Guide) (20 June 2023) <https://llm-guide.com/articles/master-the-future-llm-programs-in-legal-technology> (accessed 22 April 2024).

16 Angela Morris, “Hot Tech Jobs for New Lawyers” (SmartLawyer) <https://nationaljurist.com/smartlawyer/hot-tech-jobs-new-lawyers/> (accessed 22 April 2024).

17 Richard Susskind, Tomorrow’s Lawyers: An Introduction to Your Future (Oxford University Press 2023).

18 Dyane O’Leary, “‘Smart’ Lawyering: Integrating Technology Competence into the Legal Practice Curriculum” (2021) 19 UNHL Rev 197.

19 Ian Gallacher, “Who Are Those Guys: The Results of a Survey Studying the Information Literacy of Incoming Law Students” (2007) 44 Cal WL Rev 151.

20 William Connell and Megan Hamlin Black, “Artificial Intelligence and Legal Education” (2019) 36(5) The Computer & Internet Lawyer 14, 18.

21 Elizabeth McKenzie and Susan Vaughn, “PCs and CALR: Changing the Way Lawyers Think” (2017) Suffolk University Law School Research Paper 07-31.

22 Agnieszka McPeak, “Disruptive Technology and the Ethical Lawyer” (2019) 50 U Tol L Rev 457.

23 Brian Dickson, “The Public Responsibilities of Lawyers” (1983) 13 Man LJ 175.

24 Bullows (n 10) 258.

25 Susskind (n 17) 135.

26 Bullows (n 10) 259–60.

27 Anthony Volini, “A Perspective on Technology Education for Law Students” (2020) 36 Santa Clara High Technology Law Journal 165, 169, 171.

28 Mikolaj Barczentewicz, “Teaching Technology to (Future) Lawyers” (2021) 14 Erasmus Law Review 45, 50.

29 ibid, 52.

30 Václav Janeček, Rebecca Williams and Ewart Keep, “Education for the Provision of Technologically Enhanced Legal Services” (2021) 40 Computer Law & Security Review, 3, Article 105519.

31 Stergios Aidinlis and Agata Gurzawska, “Responsible Innovation in Multidisciplinary Research and Innovation Projects: Moving from Principle to Practice” in ISPIM Conference Proceedings (The International Society for Professional Innovation Management 2021).

32 Rene Von Schomberg, “A Vision of Responsible Research and Innovation” in Richard Owen, John Bessant and Maggy Heintz (eds), Responsible Innovation: Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society (Wiley 2013) 51–74.

33 Janeček, Williams and Keep (n 30) 5, 9.

34 The Legal Technologist, “Defining the Legal Ops Career Path” (1 February 2023) <www.legaltechnologist.co.uk/career/defining-the-legal-ops-career/> (accessed 22 April 2024).

35 Job Advert for a Postdoctoral Researcher at the University of Chicago <https://docs.google.com/document/d/15vs–ffK9PT4mfiOH8hShZMZZjwD1fCbQce4f6UYsuc/edit?usp=sharing> (accessed 22 April 2024).

36 Expression of Interest for Roles in Epoch’s Research Team <https://careers.rethinkpriorities.org/jobs/53700?token=WWykSjPZXBBbF8uQUQbjbXjB&utm_campaign=80000+Hours+Job+Board&utm_source=80000+Hours+Job+Board> (accessed 22 April 2024).

37 ibid.

38 “80,000 Hours: How to Make a Difference with Your Career” <https://80000hours.org/> (accessed 22 April 2024); Digital Rights Community | Team CommUNITY <www.digitalrights.community/> (accessed 22 April 2024); Responsible Tech Job Board – All Tech Is Human <https://alltechishuman.org/responsible-tech-job-board> (accessed 22 April 2024).

39 Random Picker <www.gigacalculator.com/randomizers/random-picker.php> (accessed 22 April 2024).

40 Steve Stemler, “An Overview of Content Analysis” (2000) 7(1) Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, Article 17.

41 Irina Lock and Peter Seele, “Quantitative Content Analysis as a Method for Business Ethics Research” (2015) 24 Business Ethics: A European Review S24.

42 Satu Elo and Helvi Kyngäs, “The Qualitative Content Analysis Process” (2008) 62(1) Journal of Advanced Nursing 107, 109.

43 Frontend Engineer at Cortico (gusto.com) <https://cortico.ai/careers/software-engineer-front-end/> (accessed 22 April 2024).

44 Senior Software Engineer – Safety Machine Learning at Discord <https://startup.jobs/senior-software-engineer-safety-machine-learning-discord-3959235> (accessed 22 April 2024).

45 Canva – Senior Data Analyst – User Trust and Safety (Open to remote across ANZ) (lever.co) <https://work180.com/en-au/for-women/employer/canva/job/496102/senior-data-analyst---user-trust-and-safety-r> (accessed 22 April 2024).

46 Horizontal Jobs – iOS Developer (wearehorizontal.org) <https://wearehorizontal.org/job-post-sr-ios.html> (accessed 22 April 2024).

47 Online Hate and Harassment Researcher (Quantitative) in | Careers at ADL Nationwide Offices (icims.com) <https://careers-adl.icims.com/jobs/2032/online-hate-and-harassment-researcher-%28quantitative%29/job?mobile=false&width=1296&height=500&bga=true&needsRedirect=false&jan1offset=0&jun1offset=60> (accessed 22 April 2024).

48 Coding/Programming Skills Meaning and Definition | Define coding/programming skills – Mercer | Mettl Glossary <https://mettl.com/glossary/c/coding-programming-skills/> (accessed 22 April 2024).

49 Sr Software Engineer, Data Management & Governance – Apple Media Products – Careers at Apple <https://jobs.apple.com/en-gb/details/200546387/senior-software-engineer-data> (accessed 22 April 2024).

50 “What Is a Data Warehouse?” (IBM) <www.ibm.com/topics/data-warehouse> (accessed 22 April 2024).

51 Canva – Senior Data Analyst – User Trust and Safety (Open to remote across ANZ) (lever.co) <https://jobs.lever.co/canva/8fbaa20d-279c-4c27-a8fb-cb421c6d2fae?lever-source=AllTechIsHuman> (accessed 22 April 2024).

52 Machine Learning Engineer, Document AI – EMEA Remote – Hugging Face (workable.com) <https://apply.workable.com/huggingface/j/DF17557C57/> (accessed 22 April 2024).

53 Tech Lead (notion.site) <https://clientjoy.notion.site/Tech-Lead-82f73f52bef94e86b6937c4125438046> (accessed 22 April 2024).

54 Job Application for Corporate Counsel, Privacy at PlayStation Global (greenhouse.io) <https://boards.greenhouse.io/sonyinteractiveentertainmentglobal/jobs/5021505004> (accessed 22 April 2024).

55 ibid.

56 Senior Privacy Counsel at Hewlett Packard Enterprise in London, England 1117731 (talentify.io) <https://www.glassdoor.co.uk/job-listing/senior-privacy-counsel-hewlett-packard-enterprise-hpe-JV_IC2671300_KO0,22_KE23,53.htm?jl=1008359138659> (accessed 22 April 2024).

57 Dogs Trust: Data Protection Analyst – Data Protection Analyst – HQ <https://careers.dogstrust.org.uk/vacancies/3253/data_protection_analyst/> (accessed 22 April 2024).

58 Vice President, Data Privacy & Security (netflix.com) <https://startup.jobs/vice-president-data-privacy-security-netflix-3986279> (accessed 22 April 2024).

59 PMI Careers Job details (avature.net) <https://pmi.avature.net/en_US/ExternalCareers/JobDetail/United-Kingdom-Counsel-Digital-Technology/66527?source=Indeed> (accessed 22 April 2024).

60 Job Application for Corporate Counsel, Privacy at PlayStation Global (greenhouse.io) <https://boards.greenhouse.io/sonyinteractiveentertainmentglobal/jobs/4801243004?gh_src=c81250474us> (accessed 22 April 2024).

61 Job Application for Senior Software Engineer – Wikimedia Enterprise at Wikimedia Foundation (greenhouse.io) <https://startup.jobs/senior-software-engineer-wikimedia-enterprise-wikimedia-2101210> (accessed 22 April 2024).

62 Legal Knowledge Engineer at LexisNexis <https://uk.indeed.com/jobs?q=legal+engineer&l=&vjk=4190015e4d27d496> (accessed 22 April 2024).

63 Eg Canva – Senior Data Analyst – User Trust and Safety (Open to remote across ANZ) (lever.co) <https://jobs.lever.co/canva/8fbaa20d-279c-4c27-a8fb-cb421c6d2fae?lever-source=AllTechIsHuman>; Senior Data Scientist at Modulos <https://work180.com/en-au/for-women/employer/canva/job/496102/senior-data-analyst---user-trust-and-safety-r> (accessed 22 April 2024).

64 Eg Research Assistant at GOVAI <https://qzpf3sq4t4b.typeform.com/to/uGNVQ6rs?typeform-source=www.governance.ai> (accessed 22 April 2024); Digital Scholarship Specialist at Princeton University <https://librarypublishing.org/2023-princeton-digital-scholarship-specialist/> (accessed 22 April 2024).

65 Geana Mitchell, Leane B Skinner and Bonnie J White, “Essential Soft Skills for Success in the Twenty-First Century Workforce as Perceived by Business Educators” (2010) 52 Delta Pi Epsilon Journal 43.

66 “What Are Soft Skills? (Definition, Examples and Resume Tips)” (Indeed.com) <www.indeed.com/career-advice/resumes-cover-letters/soft-skills> (accessed 22 April 2024).

67 Eg Chief Scientist at the US Government Accountability Office <www.usajobs.gov/job/707290300> (accessed 22 April 2024).

68 Job Application for Corporate Counsel, Privacy at PlayStation Global (greenhouse.io) <https://boards.greenhouse.io/sonyinteractiveentertainmentglobal/jobs/4801243004?gh_src=c81250474us> (accessed 22 April 2024).

69 Regulatory Lawyer | Compare the Market <www.comparethemarket.com/meerkat-your-career/jobs/regulatory-lawyer/> (accessed 22 April 2024).

70 Director, Regulatory Affairs CMC in Multiple Locations | GSK Careers <https://jobs.gsk.com/en-gb/jobs/387763> (accessed 22 April 2024).

71 Policy Analyst or Counsel, or Senior Policy Analyst or Counsel, Disability Rights in Technology Policy – Center for Democracy and Technology (cdt.org) <https://cdt.org/job/policy-counsel-senior-policy-counsel-disability-rights-in-technology-policy/> (accessed 22 April 2024).

72 OTF | Program Manager (opentech.fund) <https://www.opentech.fund/news/open-technology-fund-is-hiring-join-the-otf-team/> (accessed 22 April 2024).

73 Senior Program Manager, Journalism and Disinformation – PEN America <https://pen.org/senior-program-manager-journalism-and-disinformation/?utm_medium=referral&utm_source=idealist> (accessed 22 April 2024).

74 Ethics & Compliance Investigator – TikTok <https://www.glassdoor.co.uk/job-listing/ethics-compliance-employment-investigator-emea-tiktok-JV_IC2671300_KO0,46_KE47,53.htm?jl=1007234692484> (accessed 22 April 2024).

75 Eg Ingvild Bode and Hendrik Huelss, “Constructing Expertise: The Front- and Back-Door Regulation of AI’s Military Applications in the European Union” (2023) 30 Journal of European Public Policy 1230.

76 “How to Build a Career in Responsible Tech” (Built In) <https://builtin.com/career-development/responsible-tech-careers> (accessed 22 April 2024).

77 Mitchell, Skinner and White (n 65).

78 Sungsup Ra and others, “The Rise of Technology and Impact on Skills” (2019) 17(Sup1) International Journal of Training Research 26.

79 “LinkedIn Research Reveals the Value of Soft Skills” (fastcompany.com) <www.fastcompany.com/90298828/linkedin-research-reveals-the-value-of-soft-skills#:~:text=LinkedIn%E2%80%99s%202019%20Global%20Talent%20Trends%20report%20showed%20that,three%20most%20in-demand%20soft%20skills%20for%20companies%20today> (accessed 22 April 2024).

80 “What Are Soft Skills? Definition, Importance, and Examples” (investopedia.com) <www.investopedia.com/terms/s/soft-skills.asp> (accessed 22 April 2024).

81 Machine Learning Engineer, Document AI – EMEA Remote – Hugging Face (workable.com) <https://apply.workable.com/huggingface/j/76A1456578/> (accessed 22 April 2024).

82 Daniel Susskind and Richard Susskind, “The Future of the Professions” (2018) 162 Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 125.

83 Does Your Company Need a Specialist Technology Lawyer? (raconteur.net) <www.raconteur.net/legal/specialist-technology-lawyers/> (accessed 22 April 2024).

84 Legal Technologist | Harcourt Matthews <https://harcourtmatthews.com/jobs/legal-technologist-5373/?originalsource=Indeed.com> (accessed 22 April 2024).

85 Law, Artificial Intelligence and New Technologies – Keele University <www.keele.ac.uk/study/postgraduatestudy/postgraduatecourses/lawartificialintelligenceandnewtechnologies/> (accessed 22 April 2024).

86 Law (Law and Technology Pathway) LLB (Hons) degree course 2025 entry | University of Surrey <www.surrey.ac.uk/undergraduate/law-law-and-technology-pathway> (accessed 22 April 2024); Law with Computing Science | Undergraduate Degrees | Study Here | The University of Aberdeen (abdn.ac.uk) <www.abdn.ac.uk/study/undergraduate/degree-programmes/1146/M1G1/bachelor-of-laws-with-computing-science/> (accessed 22 April 2024).

87 Law | Undergraduate Study (cam.ac.uk) <www.undergraduate.study.cam.ac.uk/courses/law> (accessed 22 April 2024); Law Degree (Hons) | LLB | University of Southampton <www.southampton.ac.uk/courses/law-degree-llb#modules> (accessed 22 April 2024).

88 LLB in Laws (lse.ac.uk) <www.lse.ac.uk/resources/calendar/programmeRegulations/undergraduate/2022/LLBLaws.htm> (accessed 22 April 2024); Unit and programme catalogues | University of Bristol <www.bris.ac.uk/unit-programme-catalogue/RouteStructureCohort.jsa?byCohort=Y&cohort=Y&routeLevelCode=3&ayrCode=22%2F23&modeOfStudyCode=Full+Time&programmeCode=9LAWD001U> (accessed 22 April 2024).

89 Internet Law and Policy (LAWS0339) | UCL Module Catalogue – UCL – University College London <https://www.homepages.ucl.ac.uk/~ucqnmve/syllabi/ilp.html> (accessed 22 April 2024); LLB (Hons) Law with European Legal Systems (uea.ac.uk) <www.uea.ac.uk/course/undergraduate/llb-law-with-european-legal-systems/2023#course-modules-4> (accessed 22 April 2024).

90 Course Catalogue – Robotics and the Law (LAWS10196) (ed.ac.uk) <www.drps.ed.ac.uk/22-23/dpt/cxlaws10196.htm> (accessed 22 April 2024).

91 M101 – Durham University <www.durham.ac.uk/study/courses/m101/#course-details-1237476> (accessed 22 April 2024); LLB Law – Undergraduate degree study – M100 – University of Birmingham <www.birmingham.ac.uk/undergraduate/courses/law/law-llb.aspx#CourseDetailsTab> (accessed 22 April 2024); Law LLB (Hons) M101 – Undergraduate Degree – Newcastle Uni (ncl.ac.uk) <www.ncl.ac.uk/undergraduate/degrees/m101/> (accessed 22 April 2024); Law LLB | University of Leicester <https://le.ac.uk/courses/law-llb/2023> (accessed 22 April 2024).

92 Law LLB | University of Leeds <https://courses.leeds.ac.uk/3010/law-llb> (accessed 22 April 2024); Law LLB (Hons) (hud.ac.uk) <https://courses.hud.ac.uk/full-time/undergraduate/law-llb-hons> (accessed 22 April 2024).

93 Law (Law and Technology Pathway) LLB (Hons) degree course 2024 entry | University of Surrey <www.surrey.ac.uk/undergraduate/law-law-and-technology-pathway> (accessed 22 April 2024); Law, LLB (Hons) – Swansea University <www.swansea.ac.uk/undergraduate/courses/law/llb-law/#modules=is-expanded> (accessed 22 April 2024).

94 Law, LLB (Hons) – Swansea University <www.swansea.ac.uk/undergraduate/courses/law/llb-law/#modules=is-expanded> (accessed 22 April 2024).

95 Module Specification (keele.ac.uk) <www.keele.ac.uk/catalogue/current/law-30097.htm> (accessed 22 April 2024).

96 Law – LLB (Hons) – Undergraduate courses – University of Kent <www.kent.ac.uk/courses/undergraduate/177/law#tab–stage2> (accessed 22 April 2024); LLB (Hons) Law | University of Portsmouth <www.port.ac.uk/study/courses/undergraduate/llb-hons-law> (accessed 22 April 2024).

97 Law LLB (Hons) – 2024/25 entry – Courses – University of Liverpool <www.liverpool.ac.uk/courses/2023/law-llb-hons#course-content> (accessed 22 April 2024).

98 Law – LLB (Hons) – Undergraduate courses – University of Kent <www.kent.ac.uk/courses/undergraduate/177/law#tab–stage2> (accessed 22 April 2024).

99 LLB Law – course details (2024 entry) | The University of Manchester <www.manchester.ac.uk/study/undergraduate/courses/2023/09672/llb-law/course-details/#course-profile> (accessed 22 April 2024).

100 Law, Technology and Innovation module (LW22020) | University of Dundee <www.dundee.ac.uk/module/lw22020> (accessed 22 April 2024).

101 Law LLB (Hons) – 2023/24 entry – Courses – University of Liverpool <www.liverpool.ac.uk/courses/2023/law-llb-hons#course-content> (accessed 22 April 2024).

102 2022–23 | Law School | University of Exeter <https://www.exeter.ac.uk/study/studyinformation/modules/info/?moduleCode=LAW3190&ay=2022/3&sys=0> (accessed 22 April 2024); LLB (Hons) Law | Goldsmiths, University of London <www.gold.ac.uk/ug/llb-law/> (accessed 22 April 2024).

103 Law | Undergraduate study | The University of Sheffield <www.sheffield.ac.uk/undergraduate/courses/2023/law-llb#modules> (accessed 22 April 2024).

104 Law LLB (UCAS M100) (warwick.ac.uk) <https://warwick.ac.uk/study/undergraduate/courses/law/> (accessed 22 April 2024).

105 Oxford LawTech Education Programme | Home <www.oltep.ox.ac.uk> (accessed 22 April 2024). Note that technically OLTEP is an executive education/CPD programme, not a PGT programme.

106 Law & Technology – King’s College London (kcl.ac.uk) <www.kcl.ac.uk/study/postgraduate-taught/courses/law-and-technology> (accessed 22 April 2024).

107 Law and Technology (LLM) | Courses | Queen’s University Belfast (qub.ac.uk) <www.qub.ac.uk/courses/postgraduate-taught/law-technology-llm/> (accessed 22 April 2024).

108 Law and Technology LLM – Courses | University of Westminster, London <www.westminster.ac.uk/law-courses/2023-24/september/full-time/law-and-technology-llm> (accessed 22 April 2024).

109 LLM in Innovation, Technology and the Law | Edinburgh Law School <www.law.ed.ac.uk/study/masters-degrees/llm-innovation-technology-law> (accessed 22 April 2024).

110 LLM Law, Innovation & Technology | Study at Bristol | University of Bristol <www.bristol.ac.uk/study/postgraduate/2023/ssl/llm-law-innovation–technology/> (accessed 22 April 2024).

111 Law, Artificial Intelligence and New Technologies – Keele University <www.keele.ac.uk/study/postgraduatestudy/postgraduatecourses/lawartificialintelligenceandnewtechnologies/> (accessed 22 April 2024).

112 Technology, Media and Telecommunications Law LLM – Queen Mary University of London (qmul.ac.uk) <www.qmul.ac.uk/postgraduate/taught/coursefinder/courses/technology-media-and-telecommunications-law-llm/> (accessed 22 April 2024).

113 LLM Law, Technology and Innovation | University of South Wales <www.southwales.ac.uk/courses/llm-law-technology-and-innovation/> (accessed 22 April 2024).

114 Emerging Technologies and the Law LLM | Newcastle University (ncl.ac.uk) <www.ncl.ac.uk/postgraduate/degrees/5887f/> (accessed 22 April 2024).

115 Information Technology and Intellectual Property Law LLM: University of Sussex <www.sussex.ac.uk/study/masters/courses/information-technology-and-intellectual-property-law-llm> (accessed 22 April 2024).

116 Cyber Law Masters at Northumbria University <www.northumbria.ac.uk/study-at-northumbria/courses/master-of-laws-law-cyber-law-newcastle-dtflcb6> (accessed 22 April 2024).

117 LegalTech and Commercial Law, LLM – Swansea University <www.swansea.ac.uk/postgraduate/taught/law/llm-legaltech-commercial-law/> (accessed 22 April 2024).

118 International Commercial and Technology Law | The University of Manchester <www.manchester.ac.uk/study/online-blended-learning/courses/international-commercial-technology-law/> (accessed 22 April 2024).

119 Corporate Law, Computing and Innovation LLM/MSc at Ulster University 2023/24 entry – Part-time Postgraduate Study in Belfast <www.ulster.ac.uk/courses/202324/corporate-law-computing-and-innovation-30477> (accessed 22 April 2024).

120 Technology Law LLM Postgraduate taught Course | Nottingham Trent University <www.ntu.ac.uk/course/nottingham-law-school/pg/llm-technology-law> (accessed 22 April 2024).

121 Janeček, Williams and Keep (n 30).

122 Law, Artificial Intelligence and New Technologies – Keele University <www.keele.ac.uk/study/postgraduatestudy/postgraduatecourses/lawartificialintelligenceandnewtechnologies/> (accessed 22 April 2024); LLM Law & LegalTech Master’s | University of Portsmouth <www.port.ac.uk/study/courses/postgraduate-taught/llm-law-and-legaltech> (accessed 22 April 2024); LLM Legal Technology | Ulster University <https://www.ulster.ac.uk/faculties/arts-humanities-and-social-sciences/law/updates/events/legal-technology-information-informatics> (accessed 22 April 2024).

123 LegalTech and Commercial Law, LLM – Swansea University <www.swansea.ac.uk/postgraduate/taught/law/llm-legaltech-commercial-law/> (accessed 22 April 2024).

124 Unit and programme catalogues | University of Bristol <www.bris.ac.uk/unit-programme-catalogue/RouteStructure.jsa?byCohort=N&ayrCode=23%2F24&programmeCode=9LAWD024T&_ga=2.224095900.682335260.1678808956-1556046153.1678808955> (accessed 22 April 2024).

125 LLM in Innovation, Technology and the Law | Edinburgh Law School <www.law.ed.ac.uk/study/masters-degrees/llm-innovation-technology-law> (accessed 22 April 2024).

126 Frédéric Darbellay, Zoe Moody and Todd Lubart (eds), Creativity, Design Thinking and Interdisciplinarity (Springer 2017).

127 Annemarie Horn and others, “Developing Interdisciplinary Consciousness for Sustainability: Using Playful Frame Reflection to Challenge Disciplinary Bias” (2022) 18 Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy 515.

128 Daron Acemoglu and David Autor, “Skills, Tasks and Technologies: Implications for Employment and Earnings” in David Card and Orley Ashenfelter (eds), Handbook of Labor Economics, vol 4 (North Holland 2011) 1043; Adel Ben Youssef, Mounir Dahmani and Ludovic Ragni, “ICT Use, Digital Skills and Students’ Academic Performance: Exploring the Digital Divide” (2022) 13(3) Information, Article129.

129 Clinical legal education | University of Surrey <www.surrey.ac.uk/school-law/study/clinical-legal-education> (accessed 22 April 2024); Law | London South Bank University (lsbu.ac.uk) <www.lsbu.ac.uk/study/study-at-lsbu/our-schools/law-and-social-sciences/study/subjects/law> (accessed 22 April 2024); CLOCK – Keele University <www.keele.ac.uk/law/employability/clock/> (accessed 22 April 2024).

130 Craig John Newbery-Jones, “Trying to Do the Right Thing: Experiential Learning, E-Learning and Employability Skills in Modern Legal Education” (2015) 6(1) European Journal of Law and Technology <https://ejlt.org/index.php/ejlt/article/view/389> (accessed 22 April 2024).

131 Cf University of Surrey, “Digital Law Clinic” <www.surrey.ac.uk/school-law/study/clinical-legal-education> (accessed 22 April 2024); Northumbria University, “Clinical Legal Education” <www.northumbria.ac.uk/about-us/academic-departments/northumbria-law-school/study/student-law-office/clinical-legal-education/> (accessed 22 April 2024).

132 That being said, there is an improvement, especially post-pandemic, in terms of integrating legal technologies such as online case management tools in clinical legal education, so the potential of developing relevant soft skills shall not be excluded.

133 Lina Rifda Naufalin, Aldila Dinanti and Aldila Krisnaresanti, “Experiential Learning Model on Entrepreneurship Subject to Improve Students’ Soft Skills” (2016) 11(1) Dinamika Pendidikan 65.

134 Eg Kent, Keele and Warwick.

135 Stephen Cave and Kanta Dihal, “The Whiteness of AI” (2020) 33 Philosophy & Technology 685.

136 Casey Fiesler, Natalie Garrett and Nathan Beard, “What Do We Teach When We Teach Tech Ethics? A Syllabi Analysis” in Sarah Heckman, Pamela Cutter and Alvaro Monge (eds), Proceedings of the 51st ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education (New York, NY, Association for Computing Machinery, 2020) pp. 289–95.