ABSTRACT

Considerable attention has been paid to the economic benefits of participating in higher education, particularly the ‘economic premium’ of graduates compared to non-graduates. Although the civic contribution of graduates has been widely acknowledged and discussed, there has been a dearth of empirical analysis that investigates this contribution. Furthermore, the massification of higher education in the UK, US, and many other countries, has had profound impacts on the higher education experience. But little is known about how changes to the form and function of mass higher education have impacted on the civic contribution of university graduates. This research attempts to address this by focussing specifically on associational membership of university graduates during their early adulthood. By calculating the ‘civic premium’ of UK graduates compared to their non-graduate peers over time we are able explore the relationship between associational membership and higher education participation following the massification of UK higher education.

Introduction

The nature of higher education in the UK and in most other Western countries has changed considerably in the last sixty years (Altbach, Reisberg, and Rumbley Citation2009). Underpinning these changes has been the controlled growth in the number of new entrants to higher education. As early as 1973 Trow saw this as representing a shift from an ‘elite’ system of higher education to a ‘mass’ system of higher education. This transformation, Trow contended, would inevitably lead to both changes in the organisation of the higher education system (including the curriculum) and the ‘functions’ of the higher education system for the rest of society. Although Trow describes the functions of higher education in economic terms (e.g. the preparation of graduates for elite roles in specific occupations) he also recognises that the massification of higher education reflected and supported the wider democratisation of society and the extension of the political franchise.

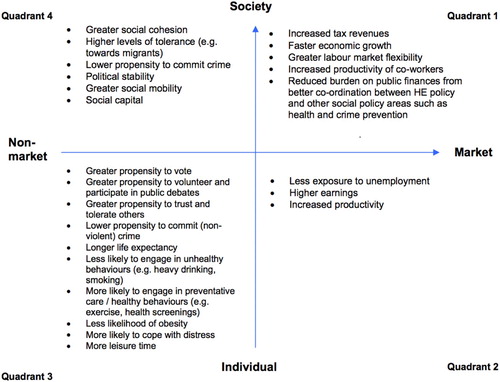

In the UK there have been two important official attempts to formalise the functions of higher education over this time period (Robbins Citation1963; Dearing Citation1997). Both recognised a broad set of functions for higher education, reflecting economic and social functions for both individuals in receipt of higher education and the rest of society. The bi-dimensional nature of these descriptions was helpfully summarised by Brennan, Durazzi, and Séné (Citation2013) in their more recent review of the wider benefits of higher education for the UK Government ().

Figure 1. A bi-dimensional categorisation of the wider benefits of higher education (from Brennan, Durazzi, and Séné Citation2013, 22).

Despite an increasing emphasis on the economic objectives of higher education (reflected in Quadrants 1 and 2) the function of higher education to contribute to ‘shaping a democratic, civilised, inclusive society’ (Dearing Citation1997, 72) has remained over time. Based on previous studies examining the impact of higher education, Brennan, Durazzi, and Séné (Citation2013) identified a number of key behaviours that are more often associated with graduates than they are with non-graduates. These included a greater propensity to vote, to engage in public debate, to volunteer, to trust, to tolerate others and to participate in civic associations. These are commonly considered to be the characteristics of a civil society that is functioning effectively. We might expect, therefore, that the massification of higher education should have exerted a positive influence on civil society over time.

However, despite the massification of higher education many countries have witnessed an apparent decline in civil society. Putnam’s (Citation1995, Citation2000) seminal studies of associational membership in Italy and the United States confirmed that such activity was in decline, a trend Putnam felt was contributing to the decline of social trust and faith in the democratic process in those countries. Studies from numerous other countries have also observed a decline in the membership of traditional civic associations (Norris Citation2001; Skocpol Citation2003; Macedo et al. Citation2005; Whiteley Citation2012; Dalton Citation2013; Richards and Heath Citation2015).

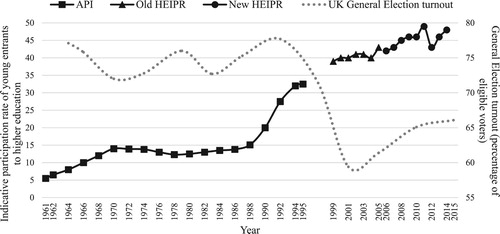

The picture in the UK would appear to be more mixed. Although data on national levels of associational membership or volunteering in the UK do not go as far back as the 1960s, voter turnout – a valid indicator of political engagement – fell considerably around the same time as significantly greater numbers began to enter higher education (). Recent figures from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) have also shown that there has been a 15.4% decline in the total number of frequent hours volunteered between 2005 and 2015 in the UK. However, Richards and Heath (Citation2015) have suggested that traditional ‘civic forms’ of social capital, such as social trust, have not significantly declined over the last thirty years in the UK. Instead, they identify that more ‘instrumental forms’ of social capital, such as membership of voluntary associations, have declined consistently since 1990. Furthermore, Richards and Heath (Citation2015) argue that ‘instrumental forms’ of social capital have become more unequally divided by socio-economic and educational status over time.

Figure 2. UK higher education participation and General Election turnout from the 1960s to 2010s. Data sources: API (Age Participation Index) (Dearing Citation1997, para 3.9); Old HEIPR and New HEIPR (Higher Education Initial Participation Rate) (Department for Education Statistical First Release SFR47/2017); UK General Election turnout (House of Commons Research Papers 01/37, 01/54, 05/33 & 10/36).

If education, and higher education in particular, does make an important contribution to civil society, some of these divergent trends would seem to be contradictory. Unfortunately, explanations for this apparent paradox largely remain speculative. The general decline in associational membership, voter turnout and volunteering, for example, could be due to other structural trends within society. These could include the transformation in the nature of civic associations themselves from traditional, hierarchical associations rooted in community or particular industries (such as churches or trade unions) towards interest- or value-based organisations with more horizontal structures (Hall Citation1999; Norris Citation2001; Welzel, Inglehart, and Deutsch Citation2005).

The most dominant explanation, however, has been the declining tendency of new cohorts of young citizens to join such associations (Putnam Citation2000; Brewer Citation2003; Li, Pickles, and Savage Citation2005; Macedo et al. Citation2005; Whiteley Citation2012). This has led to considerable interest and numerous strategies to promote civic participation amongst young people in the UK.Footnote1

Another explanation is the growing concern that the massification of higher education in the UK has led to a narrowing interpretation of its main functions, primarily around the employability of its graduates (McArthur Citation2011) – not the expansion of a wider range of functions that Trow (Citation1973) had previously predicted. The transformation to a ‘mass’ system of higher education in the UK has led to increasing financial pressures due to the expanding numbers of university students. This has been primarily resolved by shifting the financial burden from the State to individual learners. And in turn the much-expanded higher education system is increasingly characterised as a quasi-education market, where students are conceived as consumers and where institutions are nationally accountable (e.g. through the Research Excellence Framework, the more recent Teaching Excellence Framework, access agreements in England and student fee plans in Wales).Footnote2

The emphasis has been, therefore, on the economic ‘premium’ of higher education for both the individuals deciding whether to enter higher education or not (e.g. by comparing the financial cost with the potential ‘graduate premium’ they might earn later) and for society when determining how much of the increasing cost of the higher education system should be paid for through general taxation (BIS Citation2011).

Whilst this has been associated with some notable benefits, such as greater diversity of participation, better regulation and significant macro impact (Brennan Citation2008) there are concerns that these structural changes have the potential to weaken the relationship between higher education and its civic or social contribution. This has led some to question what the social contribution of higher education is and ought to be now (Schwartz Citation2003; Forstenzer Citation2017).

This paper aims, therefore, to compare the social contribution of graduates from an era of ‘mass’ higher education with graduates from a previously ‘elite’ higher education system. In addressing this aim we are able to make a much-needed empirical contribution to recent debates about the apparent decline in civil society and the possible explanations for this. Specifically we attempt to answer two important questions: (1) what is the relationship between civic participation and higher education participation and (2) has this relationship changed with the massification of higher education? In order to answer these questions we attempt to measure the ‘civic premium’ of university graduates – the difference between graduates and non-graduates – and at two different time periods – the first representing an era of elite higher education, and the second representing an era of mass higher education.

We specifically examine levels of associational membership amongst graduates and non-graduates. There are theoretical and methodological justifications for this. First, there are strong theoretical reasons for studying associational membership. Almond and Verba (Citation1963) first recognised the importance of associational membership on civic culture, particularly in terms of political behaviours and attitudes. This has been extended to include its importance in developing ‘civic skills’ (Rosenblum Citation1998; Stolle and Rochon Citation1998), which in turn led Putnam (Citation2000) to suggest that associational membership, alongside social trust, is an important indicator of social capital. However, more empirical studies have begun to question the relative importance of associational membership versus other aspects of social capital, such as social trust and political participation (e.g. Newton Citation2001). Furthermore, other empirical studies have begun to challenge whether being a member of a voluntary association or social organisation leads to greater ‘civic skills’, generalised social trust and political participation or whether the direction of causation is the other way around (e.g. Van Der Meer and Van Ingen Citation2009; Sønderskov Citation2011). Whilst there is still some disagreement about the relative importance of associational membership for civil society most of these studies share one thing in common, that is, all these different measures of civic participation are strongly associated with one another. Therefore it is reasonable to assume that differences in associational membership between graduate and non-graduates are a useful measure or proxy for the ‘civic premium’ of university graduates.

The second justification for focussing on associational membership is methodological. In order to examine the ‘civic premium’ of university graduates over time (comparing elite graduates with mass graduates) we require the use of previously collected large-scale longitudinal data. The UK has a rich history and source of such data. However, of all the different ways in which one could measure the social or civic contribution of graduates within society associational membership is the only measure that is available in any of the appropriate longitudinal studies.

The main limitation of just focussing on associational membership is that a small number of studies have shown that the relationships between various forms of civic participation are not necessarily stable over time. For example, as we discussed above, Richards and Heath (Citation2015) have showed that trends in social trust and associational membership have not been the same over time, levels of associational membership having apparently declined the most. More specifically, using data from across 29 countries Geys (Citation2012) found that the strength of the relationship between social trust and membership of some types of associations has weakened over time (although they all remain positive). To mitigate this limitation, therefore, we consider membership of different types of associations in the following analysis (Stolle and Rochon Citation1998; de Ulzurrun Citation2002).

The results of this analysis demonstrate that despite lower levels of associational membership over time, the ‘civic premium’ is greater for graduates from a ‘mass’ era of higher education than it was for graduates from the ‘elite’ era of higher education. However, we also demonstrate that this ‘civic premium’ is highly variable depending on the type of association of which individuals are members. This would suggest that being a graduate appears to be mitigating the impact of wider structural changes in associational membership, particularly for those more traditional associations that have experienced the greatest decline in participation over time. But it also suggests, there is little evidence, to date, that the massification of higher education in the UK has contributed to universal decrease (or increase) in the propensity of graduates to join civic associations.

The remainder of this paper is structured in the following way. First, we discuss in more detail the relationship between higher education and civic participation and what previous research on this relationship has been able to demonstrate thus far. Then we discuss the analytical strategy, data and method in more detail, including our measures of civic participation. This is followed by a presentation of the results of this analysis before we conclude by discussing the implications of these findings.

Higher education and civic participation

Typically, the contribution of higher education has been conceived in terms of its economic benefits, whether that be in terms of the economic impact of the sector as a whole (UUK Citation2015), the impact of institutions within their locale (Huggins and Johnston Citation2009; Lebeau and Bennion Citation2014; Zhang, Larkin, and Lucey Citation2017) or the economic impact on individual graduates (Kelly and McNicoll Citation1998; Esson and Ertl Citation2016). Moretti’s (Citation2004) examination of the ‘social return’ of higher education was framed in terms of conventional economic theory as being the collective economic value of being a graduate (i.e. using aggregated graduate earnings).

The social contribution of higher education has been far more nebulous to study. As Brennan (Citation2008) has argued, the social impact of higher education can be wide-ranging, and include social outcomes generated from the economic returns of higher education (including its impact on the ‘knowledge society’ and its contribution to social mobility). But in terms of what might be described as the direct social contribution of higher education towards what Brennan refers to as a ‘just and stable’ and ‘critical’ society, this has been much harder to measure, particularly on a large scale.

Where this has been attempted it too has distinguished between the impact of higher education institutions, such as the cultural impact on their locale (e.g. Doyle Citation2010) their civic mission (e.g. Jongbloed, Enders, and Salerno Citation2008) or their broader social responsibility (Ayala-Rodríguez et al. Citation2019), and the impact of individual graduates within society. The latter has tended to focus on the general or personal development of graduates (Locke Citation2008), such as on their self-confidence and happiness (Bellfield, Bullock, and Fielding Citation1999), or on the transformative nature of higher education on an individual’s life prospects or outlook (Christie et al. Citation2018). There have been plenty of programmatic statements about what higher education ought to do, but a dearth of empirical analyses identifying the contribution of graduates on citizenship and civic engagement – essential ingredients to Brennan’s ‘just and stable’ and ‘critical’ society.

Conventional social theory argues that higher education is positively associated with associational membership (and most other forms of civic and political participation) because it provides graduates with the necessary skills, values and attitudes that facilitate such activity in later life (Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Citation1995; Brewer Citation2003; Green, Preston, and Sabates Citation2003; Campbell Citation2009; Huang, van der Brink, and Groot Citation2009; Sondheimer and Green Citation2010). However, the consequence of this theory alone would be that with increasing numbers of graduates there should be greater civic participation over time, not less. Consequently, this has led to the development of a number of alternative explanations for the apparent paradox between rising numbers of graduates and declining civic participation.

These alternative explanations can be summarised in two main ways: explanations that question the validity of the research underpinning the conventional social theory; or explanations that suggest the relationship between higher education and civic participation has changed over time, particularly due to the massification of higher education in most developed countries.

The first of these suggest that higher education has little direct effect on civic participation, or much less than previously thought. Instead, graduate status is seen as a proxy for a range of factors that predispose individuals to both participate in higher education and undertake civic participation (Milligan, Moretti, and Oreopoulos Citation2004; Kam and Palmer Citation2008). These factors could include the influence of family, household economic background, the community in which the graduate initially grew up, or the impact of education prior to going to university.

One of the most detailed analyses of the association between graduates and associational membership in the UK was by Egerton (Citation2002). Using data from the British Household Panel Study (BHPS) from between 1997 and 1999, Egerton compared young people’s organisational involvement before and after they entered higher education (and in comparison with young people who did not enter higher education). Egerton was able to demonstrate that there was a residual and additional effect of higher education participation on civic participation. However, much of the variation in civic participation after graduation could be accounted for by variations in civic participation prior to going to university. In other words, young people going to university were more likely to engage in civic participation before participating in higher education.

The persistent association between levels of education and civic participation could, therefore, simply reflect the impact of school education rather than university education. However, this too still cannot explain the apparent paradox of rising levels of educational attainment, required for entry to higher education, and declining levels of civic participation.

The second set of alternative theories would, therefore, seem to be more credible – that is, the relationship between education (including higher education) and civic engagement, and therefore the impact of rising numbers of graduates on levels of civic engagement, is changing over time. And the key process in this changing relationship is seen to be the massification of higher education.

During the early 1970s Trow (Citation1973) observed that higher education systems expanding their provision beyond circa 15% of school-leavers tended to also reconfigure their purpose and organisation. Trow therefore predicted that the shift from an ‘elite’ to ‘mass’ higher education system would have profound consequences on the meaning, significance and motivation of students’ participation, the curriculum and functions of higher education and the impact of higher education on society. This, Trow concluded, would have important implications for the social contribution of university graduates. In particular, Trow argued that the massification of higher education would lead to a change in both the demands of prospective students and the priorities of university education that would increasingly emphasise the economic and instrumental value of higher education. And in particular, that this could lead to a shift in the pursuit of skills and values that encourage civic activity towards skills seen to enhance graduate employability. Despite a general shift towards a ‘mass’ higher education system it was always expected that elements of the earlier ‘elite’ system would remain. As Trow explains, ‘In mass higher education, the institutions are still preparing elites, but a much broader range of elites’ (Citation1973, 8).

Many would argue that this is precisely what has happened in the UK following the massification of higher education. For example, Mayhew, Deer, and Dua (Citation2004) argue there has been a much greater emphasis on instrumental economic purposes of higher education, necessary for a modern economy with a highly skilled workforce, as opposed to purposes emphasising the value of learning for its own sake, character building and self-enrichment. In addition, participation in higher education has increasingly been encouraged in terms of the financial benefits of graduates rather than an earlier emphasis on building character and preparing a relatively small group of young people to enter the political and administrative elite. Although some or all of the ‘elite’ functions remain within the UK ‘mass’ system we might still expect to see a shift in the overall purposes of higher education and its outcomes.

Trow (Citation1973) also suggested that as the higher education student body becomes more socially diverse then the social bonds between students would weaken, thereby leading to weaker foundations for civic engagement amongst graduates. This not only meant that students in the mass higher education system engaged less with the student community than their predecessors, but also that they were less likely to develop habits of behaviour and interaction that would facilitate the development of civic engagement in later life and in other communal settings (Putnam Citation2000), an argument used by Andreas (Citation2018) in relation to the current lack of soft skills amongst US college graduates.

Another suggestion made by Mayhew, Deer, and Dua (Citation2004) is that with increasing numbers of university graduates the ‘graduate premium’ – typically regarded as the economic advantage graduates enjoy as a result of securing better paid jobs – has declined on average and led to greater variation in the premium too; the growth in ‘graduate jobs’ has not kept pace with the growth in undergraduate participation. Paterson (Citation2013) makes a similar argument in the context of their social contribution, suggesting that the opportunities for civic engagement have not expanded at the same rate as higher education participation – Paterson notes, ‘there is a limit on how many people can be secretaries and chairs of local tennis clubs or branches of political parties’ (Citation2013, 19).

Finally, Ahier, Beck, and Moore (Citation2003), in their study of ‘graduate citizens’, argue that the massification of higher education is associated with a changing conception of ‘citizenship’, suggesting that neo-liberal citizenship is now more prevalent within higher education,

The question which has to be asked is whether the very ways in which higher education has been extended to a greater percentage of the population, and restructured to serve the economy, run contrary to earlier democratic and social hopes and aspirations. (Ahier, Beck, and Moore Citation2003, 63)

Methods

To contribute to this debate and to provide some empirical basis for assessing these contrasting theories this analysis attempts to measure the ‘civic premium’ of university graduates on associational membership over time.

Whilst this may initially appear to be a straightforward empirical question there are two major analytical challenges to overcome. Comparing two cohorts of graduates from two different eras would either mean (i) comparing cohorts at the same time but at different ages and stages of their life course or (ii) comparing cohorts at the same age but at different time periods. Previous research has demonstrated that there has been a general decline in levels of civic participation in the UK over the last sixty years. Any comparison, therefore, would have to distinguish between the effects of higher education from two different eras with the effects of wider structural changes that may also have led to such decline. Similarly, previous research has shown that civic participation (and by definition, associational membership) is dependent upon age and life stage (Jankowski and Strate Citation1995). Any comparison of two cohorts taken from the same point in time would therefore have to factor in their different ages.

We attempt to overcome these analytical challenges by measuring the ‘civic premium’ of being a graduate (i.e. the propensity of civic participation amongst graduates versus non-graduates) for two different cohorts of young adults (both aged 25–35 years), one from 1991 (born between 1956 and 1966) and the other from 2007 (born between 1972 and 1982). Although the data we use cannot tell us precisely when an individual went to university the first cohort of young adults are likely to have entered higher education between 1974 and 1984, at a time when university was still for an ‘elite’ few when participation was still less than 15% (see ). Crucially, the second cohort would most certainly have entered higher education after massification had occurred, between 1990 and 2000, at the same time as participation in UK higher education grew from 15% to 35% for young entrants, the period of massification (see ).

Although measures of associational membership are still taken at two different time points our interest is not in terms of comparing membership across time. Instead we calculate the propensity to be members of various civic associations for graduates and then for non-graduates at each time point. Any difference between graduates and non-graduates, the ‘civic premium’, in one cohort (or period of university participation) can then be compared with the ‘civic premium’ in the other cohort. Not only does this analysis consider whether being a university graduate is positively associated with associational membership, the simple analytical design means we can also see whether the positive association between university participation and associational membership has declined, increased or remained the same following the massification of UK higher education.

To further strengthen the analytical design we are fortunate to be able to draw upon a single data source for this purpose, the British Household Panel Study (BHPS).Footnote3 This means that data collected from the two cohorts are commensurate with one another. This rich dataset also provides us with detailed information about the individuals in each cohort which means that when comparing the ‘civic premium’ we can control for other background factors commonly associated with associational membership (such as gender, family status, employment and experience of compulsory schooling).

The main constraint of this analytical strategy and the use of the BHPS is that we are limited by the choice of measures available. As noted earlier, the only available measure of civic participation for these two cohorts is their membership of various civic associations. Fortunately, both cohorts in the study were asked the same questions and were asked about the same types of civic associations. Specifically we consider whether respondents were members of the following ten types of civic associationsFootnote4:

Trade unions

Environment groups

Parents’ associations

Tenants’ and residents’ associations

Religious organisations

Voluntary service associations

Social groups

Sports groups

Other community organisations

Other organisations

Since membership of these various types of associations can be low, many studies tend to aggregate them, either based on theoretical considerations or using some form of latent structure analysis (Egerton Citation2002; Welzel, Inglehart, and Deutsch Citation2005; Zukin et al. Citation2006; Campbell Citation2009). Despite the analytical advantages of this approach, it can overlook the heterogeneity of associational membership (Stolle and Rochon Citation1998; Helliwell and Putnam Citation2007). Consequently we adopt two analytical strategies. The first uses a composite measure of associational membership as the dependent variable – the number of associations of which respondents reported being members. For this analysis we use Poisson regression to estimate the difference in the number of associations of which graduate respondents are members, compared to non-graduate respondents. The second analytical strategy utilises the diversity of associations for which we have data and undertakes a series of logistic regression models to estimate whether graduate respondents are more or less likely to be members compared to non-graduates of each type of association.

In both sets of analyses we control for other key characteristics commonly associated with membership of civic associations. So, alongside respondents’ graduate status, we therefore also include the following characteristics in the regression models:

Gender

Marital status

Living with dependent children

Employment status (employed or unemployed)

Tenure (owning home or renting)

Whether the respondent likes their neighbourhood

Father’s social class (manual or non-manual employment)Footnote5

Type of secondary school attended (comprehensive, public/private, secondary modern)

As discussed earlier, graduate status could just be a proxy for other factors underpinning associational membership. Controlling for these background factors, including the type of secondary school attended, minimises this, but we recognise that this does not entirely address the limitation. Unfortunately, since we have to use data from the first Wave of the BHPS there is no data on associational membership before the older of the two cohorts were 18 years old.

Another limitation is that we are only concerned with the associational membership of adults between the ages of 25 and 35 years. Therefore, we do not consider the possible effect of being a university graduate on their membership later in life. Whilst this is important, particularly as associational membership tends to increase as people get older, we are constrained by the design of our comparison between two cohorts of university participants. However, there is little reason to think that if the massification of higher education was related to changes in graduates’ levels of associational membership when they were aged 25–35 years old that this would have a different relationship with their levels of associational membership later in life.

Findings

We begin by looking at the descriptive statistics for associational membership by cohort and graduate status. presents the average number of associationsFootnote6 of which respondents reported being members and the proportion of respondents who said they were members of five different types of associations.Footnote7 The results from this table show two clear patterns. First, levels of associational membership were consistently higher for the earlier ‘elite’ cohort than they were for the more recent ‘mass’ cohort. This provides further evidence for the decline in associational membership in the UK reported by Richards and Heath (Citation2015) and the general decline in civic participation noted by Putnam (Citation2000) and others. The second main observation is that for both cohorts associational membership is higher for graduates than it is for non-graduates. Again, this supports previous findings suggesting that graduate status is often associated with civic participation.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics on associational membership of 25–35 year olds by cohort and graduate status from the British Household Panel Study.

However, what is not entirely clear from is whether the gap in associational membership between graduates and non-graduates was greater during the ‘elite’ or ‘mass’ period of UK higher education. We could simply measure the ‘gap’ in associational membership between graduates and non-graduates in the two cohorts. However, we also need to consider the changing characteristics of the ‘mass’ graduate cohort compared to the ‘elite’ graduates. Therefore, presents the results of a Poisson regression on the number of associations of which respondents reported being members, after controlling for various background characteristics.

Table 2. Poisson regression: number of associations respondents are members of, by cohort.

It can be seen from this more detailed analysis that associational membership was still greater amongst graduates in both cohorts. For ‘elite’ graduates this ‘civic premium’ was the equivalent of being a member, on average, of 0.24 associations more than non-graduates from the same ‘elite’ era. For the more recent ‘mass’ graduates, this ‘civic premium’ was the equivalent of being a member, on average, of 0.29 associations more than non-graduates from the ‘mass’ era. This would indicate that despite overall lower levels of associational membership over time, the graduate ‘civic premium’ has apparently been maintained, suggesting that explanations for the broad decline in civic participation are more likely to exist outside the higher education system, and are less likely to be the result of changes to the nature and organisation of the UK higher education system over this time period.

presents the conditional probabilities on reported membership resulting from the results of ten logistic regression models by cohort and by different types of association. Since all the logistic regression models are based on exactly the same variables direct comparison of these conditional probabilities is possible. Consequently, each conditional probability can be interpreted as the ‘civic premium’ of an ‘elite’ or ‘mass’ cohort joining these particular types of associations, while controlling for all other variables in the models. For example, the ‘civic premium’ of being a graduate in the ‘elite’ cohort increases the probability of being a member of a trade union by 6% compared to a non-graduate from the same cohort. This compares to a 10% increase in the likelihood of a graduate in the ‘mass’ cohort being a member of a trade union compared to a non-graduate in the ‘mass’ cohort. Indeed, in all five types of associations in , there is a ‘civic premium’ for graduates from the ‘mass’ cohort. In two of these types of association this ‘civic premium’ is greater than it was for the ‘elite’ cohort; for two other types of association the ‘civic premium’ is smaller, and for the fifth type of association (religious organisation) the ‘civic premium’ appears to remain the same. For the other five types of association (not presented in ), there would appear to be no graduate ‘civic premium’ on their membership in either of the two cohorts. These include membership of sports clubs, voluntary associations and parents’ associations.

Table 3. Ten logistic regression models with predicted probabilities of associational membership, by cohort and by type of association (%).

Discussion and conclusions

This analysis provides further evidence that civic participation, at least in terms of associational membership, appears to have declined amongst 25–35 year olds over time. This age group were less likely to be members of traditional civic organisations, such as trade unions, residents’ associations, religious organisations and environmental groups, in 2007 compared to 1991. But, to reiterate, the two central questions addressed in this paper were (1) what is the relationship between associational membership and higher education participation and (2) has this relationship changed with the massification of higher education?

The analysis presented here suggests that university graduates were more likely to be members of civic associations compared to non-graduates, both in 1991 and 2007. We cannot be confident that the greater likelihood of associational membership amongst university graduates is not due to their higher levels of educational attainment prior to university entry, or that we can say very much about the direction of causation between associational membership and graduate status. However, the positive relationship between associational membership and graduate status remains after controlling for various other important predictors of associational membership (such as their gender, employment and family status). But these results also suggest that this ‘civic premium’ for graduates is not the same for all types of associational membership. Of the ten types of association we considered here, there was a positive relationship between graduate status and membership in only five types of associations: trade unions, environmental groups, parents’ associations, tenants’ and residents’ associations, and religious organisations. We found no relationship between graduate status and membership in voluntary service associations, social groups, sports groups, and other organisations (including other community organisations).

This suggests that there is a ‘civic divide’ between graduates and non-graduates in terms of the types of associations of which they are members. This is an important finding, since many studies tend to aggregate participation in different types of civic organisations into a single measure. Our analysis demonstrates the danger of thereby concealing the complexity of the relationship between graduate status (and education more generally) and civic participation (cf. Stolle and Rochon Citation1998). For example, the benefits of higher education participation may be greater for some types of associations than others. Does membership of, say, a sports club benefit from the same kinds of skills and values that benefit membership of a parents’ association? This has significant implications for further studies of the mechanisms through which higher education influences later civic participation by graduates.

Secondly, although associational membership appears to have declined for young adults between 1991 and 2007, the overall ‘civic premium’ associated with university graduates – specifically the benefit of being a graduate compared to a non-graduate of the same age and cohort – has held constant over this time. This would appear to be the case despite the massification of the UK higher education system between the late 1980s and 2000. Of course, we cannot tell yet whether this ‘civic premium’ exists for more recent university graduates, who, crucially, have had to make individual financial contributions to their higher education.

However, beneath this headline finding, the results suggest that the relationship between higher education and associational membership has changed, albeit in complex ways. For some types of association, the ‘civic premium’ has increased – such as trade union membership – but for other types of association, this relationship appears to have declined – such as membership of environmental groups. For other sorts of association, the ‘civic premium’ has remained the same – such as membership of religious organisations. Given the decline in membership in all these types of association, these findings indicate that being a graduate is perhaps mitigating the impact of broader civic decline in some of these types of association more than in others. The question remains, however, why that might be. It would appear, for example, that having a degree in an era of ‘mass’ higher education has been compensating for the weakening propensity of more recent young adults to join some of the more traditional civic associations that used to form the bedrock of social life in the 1950s, such as trade unions (Putnam Citation2000). It could also be the case that the obligatory nature or personal benefits of being a member of some civic associations, such as trade unions, has changed over time. However, the example of trade unions demonstrates how complex this might be. In general trade union membership has declined in the UK over this time period, suggesting that trade union membership is less obligatory than it once was. So when we see that the graduate ‘civic premium’ for trade union membership is greater for the more recent ‘mass’ graduates than it was for the earlier ‘elite’ graduates this would seem to suggest stronger civic dispositions, all things being equal. However, at the same time the increasing rate of graduate employment has not kept pace with the increasing rate of graduates in the UK. Consequently, these more recent graduates may feel more compelled to be a member of a trade union, all things being equal, because of the greater competition for graduate employment.

Conversely, graduates from the ‘elite’ era of UK higher education would appear to have been more likely to have had the values and skills that made them more likely to join newer civic associations that are issue-based and involve political campaigning; values and skills that are, perhaps, increasingly absent in an era of ‘mass’ higher education. However, this highlights an important methodological challenge in this kind of analysis.

Although more recent graduates can be described as representing the ‘massification’ of higher education, as Trow (Citation1973) himself acknowledged, this does not mean that ‘elite’ higher education, and the impact it has on its graduates, has disappeared. Rather, the differentiated structure of UK higher education remains, both in terms of academic selection for entry and in the educational and social experiences of attending different universities across the UK. Unfortunately, most available large-scale datasets do not ask what kind of universities graduates attended. Nor do they tend to ask what courses the graduates completed, how their curriculum was organised, how they were taught or what other activities they participated in during their university education. Only more detailed qualitative data could help differentiate these university experiences and how they might be impacting on civic participation. However, whilst the continued existence of elite higher education institutions continues in an era of mass higher education we would expect, on average, that their effect is clearly diluted. It is legitimate, therefore, to say that what it means to be graduate more recently has shifted on average; and this would hold for both civic values and attitudes and the knowledge and skills that are acquired or developed through participation in higher education.

The analysis presented here is dependent upon the information available in the BHPS. But despite this limitation, it has demonstrated quite clearly that research on civic participation must consider the heterogeneity of civic associations. And it could be the case that traditional forms of associational membership, as considered here, do not fully represent the different ways young adults are engaged in civil society. It has also provided an important example of the contribution of graduates. Whilst their economic contribution is inevitably important, both to individuals and the economy, there is a danger in considering the benefits of higher education in purely economic terms (Cook, Watson, and Webb Citation2014). As the major reviews of higher education have repeatedly demonstrated, higher education also has a wider social purpose. Whilst the ‘massification’ of UK higher education has led to significant changes to the priorities, organisation and outcomes of higher education, it is important and valuable to see that university graduates continue to provide a ‘civic premium’ compared to their non-graduate peers.

Acknowledgements

This research was undertaken with funding from the ESRC (Grand Award ES/L009099/1) as part of the WISERD Civil Society research centre, for which we are very grateful. We would also like to thank the Institute for Social and Economic Research (ISER), University of Essex, for providing the data used in this analysis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 As demonstrated by the number of policies designed to encourage civic participation or volunteering amongst young people and in schools, such as the Welsh Baccalaureate, the National Citizen Service in England, Project Scotland and the ‘#iwill’ UK-wide Government-funded campaign to encourage youth social action.

2 There is also significant divergence in the higher education systems of each country within the UK, as exemplified by differences in tuition fees and student financial support. Nevertheless, this divergence does not weaken the point being made, indeed, such differences could arguably be contributing to the higher education quasi-market.

3 University of Essex, Institute for Social and Economic Research (Citation2010). The BHPS has now been incorporated into Understanding Society, a larger panel survey.

4 These are all asked in the 1991 and 2005 BHPS. Membership of other organisations, such as political parties, Women’s Institute, Scouts and Guides, was also reported, but these have been omitted because either there was no comparative data in both years of the BHPS or the number of members was negligible. Of course, the degree to which each type of association has a civic purpose varies. But this will largely depend on what role that membership takes – for example there is a difference to being a member of a sports club to use its facilities and being a member of a sports club in order to coach children.

5 We have also considered using current occupational class (of the graduates/non-graduates when they were 25–35 years old). However, the inclusion of this as an additional control variable is problematic for two reasons. First, its inclusion does not change the results presented. And second, it is problematic to include a control variable that is so strongly associated with the main independent variable of interest (i.e. whether an individual is a graduate or not). Therefore, to avoid confusing the analytical design and to maintain model parsimony we do not include this in the presented results.

6 Of the ten types of civic associations listed earlier.

7 For brevity we only present the detailed results of five of the ten types of associations where we find they were associated with graduate status. The full analysis is available on request.

References

- Ahier, J., J. Beck, and R. Moore. 2003. Graduate Citizens: Issues of Citizenship and Higher Education. London: Routledge Falmer.

- Almond, G. A., and S. Verba. 1963. The Civic Culture: Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Altbach, P., L. Reisberg, and L. Rumbley. 2009. Trends in Global Higher Education: Tracking an Academic Revolution. Paris: UNESCO.

- Andreas, S. 2018. “Effects of the Decline in Social Capital on College Graduates’ Soft Skills.” Industry and Higher Education 32 (1): 47–56. doi:10.1177/0950422217749277.

- Ayala-Rodríguez, N., I. Barreto, G. Rozas Ossandón, A. Castro, and S. Moreno. 2019. “Social Transcultural Representations About the Concept of University Social Responsibility.” Studies in Higher Education 44: 245–259.

- Bellfield, C., A. Bullock, and A. Fielding. 1999. “Graduates’ Views on the Contribution of Their Higher Education to Their General Development: A Retrospective Evaluation for the United Kingdom.” Research in Higher Education 40 (4): 409–438. doi:10.1023/A:1018736125097.

- BIS. 2011. Students at the Heart of the System. London: Department for Business, Innovation and Skills.

- Brennan, J. 2008. “Higher Education and Social Change.” Higher Education 56 (3): 381–393. doi:10.1007/s10734-008-9126-4.

- Brennan, J., N. Durazzi, and T. Séné. 2013. Things We Know and Don’t Know About the Wider Benefits of Higher Education: A Review of Recent Literature. BIS Research Paper Number 133. London: Department for Business Innovation and Skills.

- Brewer, G. 2003. “Building Social Capital: Civic Attitudes and Behavior of Public Servants.” Journal of Public Administration, Research and Theory 13 (1): 5–26. doi:10.1093/jpart/mug011.

- Campbell, D. 2009. “Civic Engagement and Education: An Empirical Test of the Sorting Model.” American Journal of Political Science 53 (4): 771–786. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00400.x.

- Christie, H., V. Cree, E. Mullins, and L. Tett. 2018. “‘University Opened Up so Many Doors for Me’: The Personal and Professional Development of Graduates from Non-traditional Backgrounds.” Studies in Higher Education 43: 1938–1948..

- Cook, S., D. Watson, and R. Webb. 2019. “‘It’s Just not Worth a Damn!’ Investigating Perceptions of the Value in Attending University.” Studies in Higher Education 44: 1256–1267,.

- Dalton, R. J. 2013. The Apartisan American. Thousand Oaks: CQ Press.

- Dearing, R. 1997. Higher Education in the Learning Society: Report of the National Committee of Inquiry into Higher Education. Chaired by Lord Dearing. London: HMSO.

- de Ulzurrun, L. 2002. “Associational Membership and Social Capital in Comparative Perspective: A Note on the Problems of Measurement.” Politics and Society 30 (3): 497–523.

- Doyle, L. 2010. “The Role of Universities in the ‘Cultural Health’ of Their Regions: Universities’ and Regions’ Understandings of Cultural Engagement.” European Journal of Education 45 (3): 466–480. doi:10.1111/j.1465-3435.2010.01441.x.

- Egerton, M. 2002. “Higher Education and Civic Engagement.” British Journal of Sociology 53 (4): 603–620. doi:10.1080/0007131022000021506.

- Esson, J., and H. Ertl. 2016. “No Point Worrying? Potential Undergraduates, Study-related Debt, and the Financial Allure of Higher Education.” Studies in Higher Education 41 (7): 1265–1280. doi:10.1080/03075079.2014.968542.

- Forstenzer, J. 2017. “We are Losing Sight of Higher Education’s True Purpose.” The Conversation, March 9. Accessed March 21, 2018. https://theconversation.com/we-are-losing-sight-of-higher-educations-true-purpose-73637.

- Geys, B. 2012. “Association Membership and Generalized Trust: Are Connections between Associations Losing their Value?” Journal of Civil Society 8 (1) 1–15. doi:10.1080/17448689.2012.665646.

- Green, A., J. Preston, and R. Sabates. 2003. “Education, Equality and Social Cohesion: A Distributional Approach.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 33 (4): 453–470. doi:10.1080/0305792032000127757.

- Hall, P. A. 1999. “Social Capital in Britain.” British Journal of Political Science 29: 417–461.

- Helliwell, J., and R. Putnam. 2007. “Education and Social Capital.” Eastern Economic Journal 33 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1057/eej.2007.1.

- Huang, J., H. van der Brink, and W. Groot. 2009. “A Meta-analysis of the Effect of Education on Social Capital.” Economics of Education Review 28: 454–464. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2008.03.004.

- Huggins, R., and A. Johnston. 2009. “The Economic and Innovation Contribution of Universities: A Regional Perspective.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 27 (6): 1088–1106. doi:10.1068/c08125b.

- Jankowski, T., and J. Strate. 1995. “Modes of Participation Over the Adult Life Span.” Political Behavior 17 (1): 89–106. doi:10.1007/BF01498785.

- Jongbloed, B., J. Enders, and C. Salerno. 2008. “Higher Education and its Communities: Interconnections, Interdependencies and a Research Agenda.” Higher Education 56 (3): 303–324. doi:10.1007/s10734-008-9128-2.

- Kam, C., and C. Palmer. 2008. “Reconsidering the Effects of Education on Political Participation.” The Journal of Politics 70 (3): 612–631. doi:10.1017/S0022381608080651.

- Kelly, U., and I. McNicoll. 1998. “Dearing: Who Pays and Who Gains? Understanding the Graduate Premium and Rates of Return.” Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education 2 (3): 74–77. doi:10.1080/713847944.

- Lebeau, Y., and A. Bennion. 2014. “Forms of Embeddedness and Discourses of Engagement: A Case Study of Universities in Their Local Environment.” Studies in Higher Education 39 (2): 278–293. doi:10.1080/03075079.2012.709491.

- Li, Y., A. Pickles, and M. Savage. 2005. “Social Capital and Social Trust in Britain.” European Sociological Review 21 (2): 109–123.

- Locke, W. 2008. Graduates’ Retrospective Views of Higher Education. Milton Keynes: HEFCE/CHERI.

- Macedo, S., Y. Alex-Assensoh, J. Berry, M. Brintall, D. Campbell, L. Fraga, A. Fung, et al. 2005. Democracy at Risk: How Political Choices Undermine Citizen Participation, and What We Can Do About It. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

- Mayhew, K., C. Deer, and M. Dua. 2004. “The Move to Mass Higher Education in the UK: Many Questions and Some Answers.” Oxford Review of Education 30: 65–82. doi:10.1080/0305498042000190069.

- McArthur, J. 2011. “Reconsidering the Social and Economic Purposes of Higher Education.” Higher Education Research & Development 30 (6): 737–749. doi:10.1080/07294360.2010.539596.

- Milligan, K., E. Moretti, and P. Oreopoulos. 2004. “Does Education Improve Citizenship? Evidence from the United States and the United Kingdom.” Journal of Public Economics 88: 1667–1695. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2003.10.005.

- Moretti, E. 2004. “Estimating the Social Return to Higher Education: Evidence From Longitudinal and Repeated Cross-sectional Data.” Journal of Econometrics 121 (1-2): 175–212. doi:10.1016/j.jeconom.2003.10.015.

- Newton, K. 2001. “Trust, Social Capital, Civil Society and Democracy.” International Political Science Review 22 (2): 201–214.

- Norris, P. 2001. Digital Divide: Civic Engagement, Information Poverty, and the Internet Worldwide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Paterson, L. 2013. “Comprehensive Education, Social Attitudes and Civic Engagement.” Longitudinal and Life Course Studies 4 (1): 17–32.

- Putnam, R. 1995. “Bowling Alone: America's Declining Social Capital.” Journal of Democracy 6 (1): 65–78. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/jod.1995.0002.

- Putnam, R. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Richards, L., and A. Heath. 2015. CSI 15: The Uneven Distribution and Decline of Social Capital in Britain. Oxford: Centre for Social Investigation, Nuffield College.

- Robbins, L. 1963. Higher Education: Report of the Committee Appointed by the Prime Minister Under the Chairmanship of Lord Robbins, Cmnd. 2154. London: HMSO.

- Rosenblum, N. L. 1998. Membership and Morals: The Personal Uses of Pluralism in America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Schwartz, S. 2003. “The Higher Purpose.” Times Higher Education, May 16. Accessed March 21, 2018. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/comment/columnists/the-higher-purpose/176727.article.

- Skocpol, T. 2003. Diminished Democracy: From Membership to Management in American Civic Life. Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Sønderskov, K. M. 2011. “Does Generalized Social Trust Lead to Associational Membership? Unravelling a Bowl of Well-tossed Spaghetti.” European Sociological Review 27 (4): 419–434.

- Sondheimer, R., and D. Green. 2010. “Using Experiments to Estimate the Effects of Education on Voter Turnout.” American Journal of Political Science 54 (1): 174–189. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00425.x.

- Stolle, D., and T. Rochon. 1998. “Are All Associations Alike? Member Diversity, Associational Type, and the Creation of Social Capital.” American Behavioral Scientist 42 (1): 47–65. doi:10.1177/0002764298042001005.

- Trow, M. 1973. Problems in the Transition From Elite to Mass Higher Education. Washington: Carnegie Commission on Higher Education.

- University of Essex. Institute for Social and Economic Research. 2010. British Household Panel Survey: Waves 1-18, 1991–2009. [data collection]. 7th ed. UK Data Service. SN: 5151. doi:10.5255/UKDA-SN-5151-1.

- UUK. 2015. The Economic Role of Universities. London: Universities UK.

- Van Der Meer, T., and E. Van Ingen. 2009. “Schools of Democracy? Disentangling the Relationship between Civic Participation and Political Action in 17 European Countries.” European Journal of Political Research 48: 281–308. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2008.00836.x.

- Verba, S., K. Schlozman, and H. Brady. 1995. Voice and Equality: Civic Voluntarism in American Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Welzel, C., E. Inglehart, and F. Deutsch. 2005. “Social Capital, Voluntary Associations and Collective Action: Which Aspects of Social Capital Have the Greatest ‘Civic’ Payoff?” Journal of Civil Society 1 (2): 121–146. doi:10.1080/17448680500337475.

- Whiteley, P. 2012. Political Participation in Britain: The Decline and Revival of Civic Culture. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Zhang, Q., C. Larkin, and B. Lucey. 2017. “The Economic Impact of Higher Education Institutions in Ireland: Evidence from Disaggregated Input–output Tables.” Studies in Higher Education 42 (9): 1601–1623. doi:10.1080/03075079.2015.1111324.

- Zukin, C., S. Keeter, M. Andolina, K. Jennings, and M. Delli Carpini. 2006. A New Engagement? Political Participation, Civic Life, and the Changing American Citizen. New York: Oxford University Press.