ABSTRACT

Reflection on the meaning of the word ‘tradition’, and related terms such as ‘traditional’, is conceptually complex but has been subject to limited critical scrutiny within academic discourse. The evidence of this study, drawing on the theory of tradition and a database of all 6947 papers published in Studies in Higher Education between 1976 and 2021, is that higher education researchers make extensive use of these words in a routinised and often un-scholarly way. The language of tradition is frequently invoked as an emotive means to both resist and argue for change in higher education often framed as a dualism where the words tradition or traditional are deployed as positives or pejoratives. Despite the intensification of empirical work since the 1970s and 1980s, and the increasingly international authorship of Studies of Higher Education, use of tradition as a rhetorical device continues to play a significant role in the literature. As the paper illustrates, this has contributed to the creation and perpetuation of myths about students, universities and academic work.

Introduction

The pageantry surrounding the state funeral of Queen Elizabeth II in 2022 was represented in the popular news media as a British ‘tradition’ dating back hundreds of years (e.g. Blizzard Citation2022). While elements of this ritual, such as crowning, go back over a thousand years no British monarch was given a lying-in-state or had their coffin pulled by gun carriages until the twentieth century (Cannadine Citation1983). This is all part of the invention of tradition (Hobsbawm and Ranger Citation1983). Yet the monarchy is not the only ancient institution that likes to re-invent itself. Universities have long sought to subtly exaggerate or fabricate their historical lineage by adopting an architectural style known as collegiate gothic. This style was especially popular with institutions founded during the late Victorian and Edwardian period (e.g. the universities of Bristol, Liverpool and Manchester), to suggest ‘antiquity and prestige’ (Lowe and Knight Citation1982, 81). Collegiate gothic is still echoed in contemporary university architecture, such as Whitman College at Princeton University completed as recently as 2007. As Finnegan (Citation1991, 112) noted, with more than a hint of irony, ‘some reputed “traditions” turn out to have been established quite recently’. What other traditions have been invented in higher education, and to what extent have academic researchers knowingly or unknowingly colluded in projecting these false impressions?

The words tradition and traditional are part of the lexicon of everyday life and academic conversation but there are many reasons why these words should be used with extreme caution. There are a number of well-established examples of invented tradition notably the extent to which research, rather than teaching, is sometimes falsely represented as the historic business of a ‘traditional’ university. In truth, research was a comparative late comer to the work of many higher education institutions, notably in Britain and its former empire. This is why Matthew Arnold described English universities as little more than glorified schools in the nineteenth century (Arnold Citation1964) and their lack of research, in the broader German sense, was still a source of criticism in the mid twentieth century (Truscot Citation1943). Most British academics did not possess a PhD in the 1950s and 1960s and their primary interest was in teaching (Collison Citation1956; Halsey and Trow Citation1971). Even as late as 2014/2015, the highest qualification of academic staff working in 35 British higher education institutions, of which 26 were then classified as universities, was a masters’ degree (HESA Citation2022). Britain, along with its former colonies, was not alone in having a very limited research tradition. In the US the research universities only really developed after the Second World War as a result of a major upscaling in federal policy and funding (Graham and Diamond Citation2004). This exemplar serves to illustrate that there is a potential problem in using the word tradition in writing about higher education as it may be deployed as a rhetorical device in an unexamined way. Tradition is not a permanent, immutable given but subject to reinvention and change over time.

The purpose of this paper is to demonstrate how tradition and its related terms are used by higher education researchers. In so doing we will draw on an analysis of a complete data set of all 6947 papers published between 1976 and 2021 in Studies in Higher Education. Our analysis will be informed by the theory of tradition, as outlined by Alexander (Citation2016), Boyer (Citation1990), Shils (Citation1981), and Scheffler (Citation2010) among others. It will demonstrate that, despite the intensification of empirical work since the 1970s and 80s, many researchers continue to invoke the word tradition in a largely rhetorical way contributing to myth-making in the process. The findings are significant to the field of higher education because they illustrate that knowledge claims are often based on taken-for-granted assumptions even in empirically-driven research.

The perceived past

Shils (Citation1981:12) defines tradition as ‘anything that is handed down from the past to the present’ both orally and in writing. This includes secular as well as religious beliefs, regardless of the means by which a tradition is sustained, through rationality and deduction, or alternately via divine belief. The power of tradition cannot, Shils argues, be under-estimated and even accounts for the creation of the country of Pakistan, based on an imagined collective past identity (Shils Citation1981, 209). According to Alexander (Citation2016) there are three elements that make it possible to understand the meaning of tradition – continuity, canon and core. The most fundamental of these is continuity as all traditions must have durability but may not necessarily possess a (written) canon or core of beliefs representing an ‘unchanging truth’ (Alexander Citation2016, 18). A canon is a set of divine or sacred beliefs that are written down contained in a text or a set of texts, such as the Bible or the Koran, but there are also secular canons too, of course. Primitive societies had traditions with continuity but these were sustained largely without any written texts. Instead they were handed down orally as a means of providing continuity. Without a canon or a core a tradition is essentially a ritual.

Reflection about the meaning of tradition in academic terms is considerably outweighed by the tendency to use the word in a taken-for-granted manner. Perhaps one of the reasons for this is that any investigation into the meaning of tradition is highly complex requiring an ability to weave a story from a wide range of disciplines and fields of study including, inter alia, sociology, anthropology, religion, art, literature and history. The meaning of tradition goes largely unexamined in the world of academe, even by historians and anthropologists who ought to be more aware of the importance of taking great care in their use of this term (Alexander Citation2016; Boyer Citation1990; Shils Citation1981). It is not fashionable among intellectuals to defend tradition either as such an attitude can be labelled as ‘conservative’ or ‘reactionary’ (Shils Citation1981, 1/2), a post-enlightenment attitude which started with the rejection of divine authority and religious superstitions (Niblett Citation1983). Social scientists continue to see traditions as indicators of dogmatism with a minimal empirical basis. At the same time, they are themselves often wedded to their own post-enlightenment forms of traditions through sociological and philosophical analysis, such as Descartes’ deductive reasoning or Popper’s critical rationalism. In other words, the original radical nature of rationality itself has become an intellectual tradition. Tradition may be understood as about both process and product, its use deliberately conveying considerable emotional import, and there are elements that are not necessarily agreed upon (Finnegan Citation1991). This latter point resonates with Alexander’s (Citation2016) distinction between an agreed written canon and a wider, and therefore perhaps less settled, set of core beliefs. Differences in textual interpretations and ‘versions’ of canons, such as the Bible (e.g. King James version), lead to long standing disputes about the ‘correct’ elements of the core.

There are processes in higher education that might be labelled traditions (e.g. self-governance, the lecture, etc.) and products in terms of its overall purposes (e.g. research, a student’s ability to think critically, etc.) too. Alexander’s (Citation2016) framework may also be widely applied in respect to organisational traditions. In higher education there is continuity in terms of the university as an institutional form from medieval times and its related traditions, such as the graduation ceremony or the lecture. Certain ancient universities are among the most traditional of institutions of Western civilisation and only the universities of Bologna and Paris predate the Roman Catholic church (Shils Citation1981). Having acknowledged this, though, the spread of mass higher education systems during the late twentieth century means that many, if not most, universities have been founded relatively recently. There is a disparate canon about the philosophical idea of the university in both the English liberal and German research tradition, shaped by thinkers such as Newman, von Humboldt, and Jaspers among other. These are just two of a number of university ‘traditions’ that might be identified. However, it is important to avoid essentialism in the use of the word tradition. The temporality and context in which a tradition exists is critical to any meaningful interpretation. This highlights the relevance of institutional theory (Meyer and Rowan Citation1977) to higher education since a variety of contextual features related to the state, national society, culture and global environment have a direct bearing. Hence, even the lecture, so often spoken of in generic terms, is a cultural construction based on the discipline as well as other factors where meanings, definitions and interpretations can vary.

Another way of understanding traditions in higher education is by reference to what is seen as being endangered or being undermined. The tendency of authors to refer to higher education as being ‘in crisis’, ‘under threat’, ‘at risk’, and so on has been criticised as a rhetorical device to ‘sex up’ book titles (Tight Citation1994) but nevertheless provides a helpful insight into which traditions are regarded as being imperilled. The word crisis conveys an emotional appeal in the way in which Finnegan (Citation1991) recognises that the use of the word tradition does too. The crisis literature has a long history stretching back at least the 1940s if not earlier. There is a sixty-year gap between the publication of The Crisis in the University by Walter Moberly (Citation1949) and Jefferson Frank and colleagues’ book English Universities in Crisis (Citation2019). What is important here in considering the many hundreds of books and papers that use this type of language are the main crisis themes and the way in which the perceived threat has shifted over time. Many of the traditions being defended in the crisis literature tend to centre on what might be loosely described as the liberal university tradition (e.g. Collini Citation2012; Frank, Gowar, and Naef Citation2019; Halsey Citation1992; Wallerstein and Starr Citation1971) such as the perceived threats posed by managerialism, marketisation and neoliberal government policies. This crisis literature also provides insights as to the core of higher education tradition such as institutional autonomy, academic freedom and, perhaps more recently, the importance of universal student access since the 1970s. However, this emerged after a long debate between the so-called ‘elitists’ and the ‘expansionists’ especially in the UK (Halsey and Trow Citation1971). This was a dominant feature between the 1950s and 1970s but the perceived threat to academic standards posed by expanding student access to higher education has now largely disappeared from the literature illustrating a shift in tradition. This is indicative of the way in which traditions evolve through the re-interpretation of the core. The waning of this ‘elitist tradition’ (Perkin Citation1976, 11) serves as an example.

Methodology

This study identifies and analyses uses of the four closely related words tradition/traditional/traditionalism/traditionalist (subsequently referred to simply as ‘tradition’) in all 6947 papers published in the journal Studies in Higher Education between 1976 and 2021. It will focus principally on the words tradition and traditional since references to traditionalism and traditionalist are comparatively rare. While other systematic review studies commonly gather articles from various journals and databases to investigate what has been published on specific topics within shorter time frames, this paper presents Studies in Higher Education as a case study to demonstrate how HE researchers have (mis)used tradition and related terms for over 40 years. Studies in Higher Education is a leading, international journal that is an influential part of academic discourse within the field. Its distinctive focus on higher education and long publication history highlights how tradition in higher education has been represented in a leading, peer-reviewed journal in the field.

This paper surveys all 6947 research papers published in Studies in Higher Education between 1976 (the inception of the journal) and 2021. This number excludes editorials, book reviews, research notes and other irregular contributions. Articles were initially scanned and all occurrences of the four related words – tradition/traditional/traditionally/traditionalism – were noted. We counted only original mentions, in the main body of the article and less usual places like graph captions and legends, titles and columns of tables and end notes, and disregarded instances that merely ‘borrowed’ the search terms from direct quotations, interview transcripts or references. To examine how tradition is understood and used, we then performed thematic analysis on the mentions, coded them iteratively and finally grouped them into four distinctive categories of usage.

The use and abuse of tradition

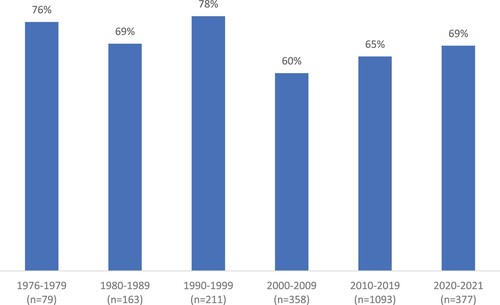

On the first page of the opening editorial of the inaugural issue of Studies in Higher Education, published in 1976, the word ‘tradition’ was used by the founding editor, Tony Becher. Subsequently, the word tradition (and related terms) have been used on average three times per paper published between 1976 and 2021. 67% of all papers published between 1976 and 2021 use the word tradition (or related terms) at least once. Across five decades the use of the word tradition has remained consistently high but with some variation (see ) demonstrating that, despite the increasingly international nature of the journal, the word tradition is used regularly by authors from around the world. Some authors are especially reliant on the use of tradition using the term more than 100 times in a single paper (see ).

Table 1. Most use of the term ‘tradition’ in a single paper.

There appear to be four main reasons why authors use the term tradition or traditional: to neutrally, or descriptively, frame an explanation of the historical and/or contemporary background related to a topic (tradition-as-description), as a term that implicitly criticises a practice as outmoded and/or in need of reform (tradition-as-pejorative), as a term defending a practice as based on values that deserve to be defended (tradition-as-positive), and, finally, as part of a dualism juxtaposing a traditional practice with a modern or more innovative one (tradition-as-dualism) (see ). Such dualisms can either be used for rhetorical effect where tradition appears in contrast with a new practice or innovation advocated by the author(s) or in a purely descriptive manner. There were 6951 instances of the use of tradition (or related terms). 63.4% (i.e. 4405) were tradition-as-description and 33.9% (i.e. 2355) tradition-as-dualism. The vast majority of pejorative and positive uses of tradition appear in dualisms. It is unusual for the word tradition to be used singularly as a pejorative (127 times or 1.8%) and even rarer as a positive (64 times or 0.9%).

Table 2. Classifying the use of tradition (and related terms).

Examples of tradition-as-description include phrases such as ‘teaching traditions’, ‘university traditions’, ‘traditions of filial piety’. Many if not most uses of the terms tradition and traditional are applied descriptively, whether accurately or not, based on an assumption of a shared understanding between author and reader. For example, Eustace (Citation1987, 18) states that the Jarratt report (Citation1985) recommended the ‘re-instatement of Heads of Department of the traditional sort and with large administrative functions, appointed – in effect and not formally – by Council’. The report was a highly influential investigation into the efficient running of English universities that made various recommendations for their improvement including the idea that Vice Chancellors should be recognised ‘not only as academic leader but also as chief executive of the university’ (Jarratt Citation1985, 33). However, although Jarratt used the words tradition and traditional a total of six times it did not do so in the context of the role of Heads of Department. Jarratt recommends, as Eustace suggests, that Heads of Department should be appointed by Council, as opposed to by rotation within departments. It also states, however, that Heads should ideally be both an academic leader and a manager but goes on to suggest that ‘where these two qualities cannot be found in a single person, management competence should take precedence in making an appointment’ (Jarratt Report Citation1985, 25). By any measure, this statement represents a view that is far removed from a ‘traditional’ view of an academic Head of Department when it was written in 1985. Moreover, a reader of Eustace’s paper unfamiliar with the Jarratt report might reasonably assume that he means something entirely different by the expression ‘Heads of Department of the traditional sort’ (Eustace Citation1987, 18) including the appointment of a senior professor, or more especially a senior male professor, and/or an appointment based on an internal system of rotation rather than via external appointment, and so on. The phrase may also potentially refer to a leadership style or approach to the management of an academic department. Here, Eustace leaves too much for the reader to interpret.

Tradition is more commonly applied as a pejorative rather than as a positive term. Popular targets in applying tradition-as-pejorative include lectures, unseen/written examinations, managerialism and elitism. The tradition-as-pejorative reflects Shils’ (Citation1981) argument that the term is often used to emotively characterise anything considered unfashionable, conservative or reactionary (Shil Citation1981, 1/2). By contrast, tradition-as-positive affirmations include academic freedom, liberal education, academic autonomy, problem-based learning, reflection and collegiality. Tradition-as-positive represents an attempt to do the opposite by asserting that a practice or an habitual way of working is worth preserving and needs to be defended in some way from some form of unwelcome change. As Scheffler (Citation2010) has argued the continuing popularity of a tradition may be because the values that underlie it remain more attractive than a so-called progressive position or idea. Many types of tradition-as-positive can invoke golden-age liberal values at a time when universities were autonomous and had yet to be heavily influenced by market or management principles. Collegiality, for example, needs to be defended from managerialism, academic autonomy from the perils of neo-liberalism, and academic freedom from anything that might threaten it including political state interference, and so on.

Tradition-as-dualism takes two forms, either a descriptive dualism such as traditional as opposed to non-traditional students or a positive-pejorative dualism such as dichotomising traditional teaching methods and so-called innovative teaching methods. The latter form of dichotomising is especially common in respect to scholarship about teaching and learning where ‘traditional teaching methods’ are regularly dismissed as ineffective or out-of-date compared with supposedly ‘new’ and ‘innovative’ approaches. There are a range of popular phrases conjoined with tradition or traditional such as ‘non-traditional student’ (e.g. Trow Citation1989, 20), ‘traditional subjects’ (e.g. Boud Citation1990, 110), ‘traditional teaching methods’ (Wang Zhang, and Yao Citation2019, 1316), ‘traditional curriculum’ (Niblett Citation1981, 7), ‘traditional standards’ (Lueddeke Citation2003, 223), and ‘traditional university’ (van Schalkwyk Citation2021, 46). A further example, ‘traditional academic’ (Moodie (Citation1976, 134) has 249 exact mentions. Most assertions of this phrase do not offer any definition, relying on an assumption of a shared understanding between author and reader. Where they do occur explanations tend to cluster around the importance of autonomy (e.g. Altbach Citation1995; Trowler Citation1997), collegiality (e.g. Harries-Jenkins Citation1979), academic good manners, such as ‘politeness in criticism’ among historians (Becher Citation1989, 274), or the legendary reluctance of academics to willingly follow managerial authority although whether this belief represents a myth or an empirical reality by reference to other professions has never really been proven.

academics have traditionally been difficult to manage. (Kolsaker Citation2008, 515; Huang, Liu, and Huang Citation2021, 2486)

The so-called ‘traditional university’ has 139 exact mentions. It is a popular tradition-as-description with at least six different interpretations of this term. The most common is a university that is ‘old’ and has a longer history than some others often leading to the use of a dualism, as in:

type of university (i.e. whether old/traditional or new/modern). (Taulke-Johnson Citation2010, 247)

old (traditional) and new (entrepreneurial) archetypes of university. (Sutphen, Solbrekke, and Sugrue Citation2019, 1402)

A liberal university is one that is free to live out the traditional values of intellectual integrity and freedom of expression. (Tasker and Packham Citation1993, 131)

The use of the word tradition can shift significantly over time. Claims to the ‘new’ and the ‘innovative’ can look quickly dated too. The so-called flipped classroom has been discussed in the higher education literature for well over twenty years, originally referred to as a ‘classroom flip’ by Baker (Citation2000) whilst, arguably, the principles that this term advances have been practiced without such a self-conscious label by teachers in higher education for many decades, or perhaps centuries, through approaches based on a Socratic dialogue with the aim of freeing up time in class for discussion by setting pre-reading and other tasks. Yet, more than twenty years on the flipped classroom is still being represented as something new and innovative by contrast with ‘traditional’ teaching approaches (Price and Walker Citation2021). Many other assertions about what is new and innovative need to be understood in their historical context such as a statement in the late 1970s about ‘the potential of video cassette technology for curricular innovation’ (Pronay Citation1979, 27) or Harding’s (Citation1980, 111) use of the phrase ‘traditional technologies’ in 1980. The use of email was contrasted with ‘traditional teaching’ in the late 1990s (Tynjälä Citation1998, 175) but perhaps understandably by 2021 email was being labelled a ‘traditional’ tool (Agasisti and Soncin Citation2021, 94). The rush to online provision as a result of Covid-19 means that face-to-face teaching is now being classified by researchers as ‘traditional’ as well (Yang and Huang Citation2021, 129).

Here, some forms of tradition have clearly waned over time as evidenced by the declining usage of certain phrases. A good example is provided by references to the so-called ‘tradition of “liberal education”’ (Simons and Elen Citation2007, 623). This was a particularly popular source of discussion in papers in Studies in the 1970s. Gradually, though, attention to a ‘liberal education tradition’ has dwindled and is now no longer evident in the papers from the 2010s and 2020s despite the exponential growth in the number of issues per volume during this period. This excludes mentions of ‘traditional liberal arts’ and ‘traditional liberal arts education’. The notion of a liberal education, famously developed by R. S. Peters, has itself multiple interpretations including development of the whole person, provision of an all-round, non-specialised education, and one founded on certain values, such as tolerance. Anything up to seven different interpretations have been offered for a ‘liberal education’ (Thiessen Citation1989). This complexity makes assertions about a ‘liberal education tradition’ even more problematic to unpick unless authors are highly explicit, a rare example of which is provided in an early issue of Studies by Rip (Citation1979, 22).

… I also have a traditional liberal-humanistic aim: scientists, like other individuals, should be able to look more broadly at themselves and their social position, and recognise the limitations of the science with which they identify. (Rip Citation1979, 22)

Although the use of liberal education has fallen away over the last twenty years the word ‘neo-liberal’ has become a modern pejorative with its own ‘neoliberal traditions’ (Collins, Azmat, and Rentschler, Citation2019, 1484) while the ‘liberal’ is associated with ‘traditional’ values and often used implicitly in a positive-pejorative dualism.

the psychological, the traditional-academic, the techno-scientific and the neo-liberal’ discourses permeating the supervisory practices. (Strengers Citation2014, 548)

Traditional goals of knowledge acquisition and dissemination clash with neoliberalist pressures to operate as a free market corporation, … (Nadolny and Ryan Citation2015, 154)

… the culturally traditional (state-led) and the other more modernist, neoliberal. (Nguyen and Gramberg Citation2018, 2141)

Conclusion

We tell ourselves a mythical story of the university in our society: that it has a tradition dating back centuries … (Erickson, Hanna, and Walker Citation2021, 2134)

The educational innovator is, more or less by definition, inviting a break with tradition and must therefore be viewed with suspicion by his colleagues. Ayscough (Citation1976, 3)

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge the valuable feedback of Dr. Euan Wright on an earlier draft of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Agasisti, T., and M. Soncin. 2021. “Higher Education in Troubled Times: On the Impact of Covid-19 in Italy.” Studies in Higher Education 46 (1): 86–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1859689

- Alemán, A. M. M., and K. Salkever. 2004. “Multiculturalism and the American Liberal Arts College: Faculty Perceptions of the Role of Pedagogy.” Studies in Higher Education 29 (1): 39–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/1234567032000164868

- Alexander, J. 2016. “A Systematic Theory of Tradition.” Journal of the Philosophy of History 10: 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1163/18722636-12341313

- Altbach, P. G. 1995. “Problems and Possibilities: The US Academic Profession.” Studies in Higher Education 20 (1): 27–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079512331381780.

- Arnold, M. 1964. Schools and Universities on the Continent. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan.

- Ayscough, P. B. 1976. “Academic Reactions to Educational Innovation.” Studies in Higher Education 1 (1): 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075077612331376803.

- Baker, J. W. 2000. “The ‘Classroom Flip’: Using Web Course Management Tools to Become the Guide by the Side.” Selected Papers from the 11th International Conference on College Teaching and Learning, 9–17.

- Balloo, K., R. Pauli, and M. Worrell. 2017. “Undergraduates’ Personal Circumstances, Expectations and Reasons for Attending University.” Studies in Higher Education 42 (8): 1373–1384. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1099623

- Becher, T. 1989. “Historians on History.” Studies in Higher Education 14 (3): 263–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075078912331377663

- Blizzard, C. 2022. “Traditions for Queens Funeral Date Back Hundreds of Years”. Toronto Sun, September 18. https://torontosun.com/opinion/columnists/blizzard-traditions-for-queens-funeral-date-back-hundreds-of-years.

- Boud, D. 1990. “Assessment and the Promotion of Academic Values.” Studies in Higher Education 15 (1): 101–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079012331377621

- Boyer, P. 1990. Tradition as Truth and Communication. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Brändle, T. 2017. “How availability of capital affects the timing of enrollment: the routes to university of traditional and non-traditional students.” Studies in Higher Education 42 (12): 2229–2249.

- British Council/DAAD. 2018. Building PhD Capacity in Sub-Saharan Africa. London: British Council/DAAD. https://www.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/h233_07_synthesis_report_final_web.pdf.

- Cannadine, D. 1983. “The Context, Performance and Meaning of Ritual: The British Monarchy and the ‘Invention of Tradition’, c. 1820–1977.” In The Invention of Tradition, edited by E. Hobsbawm and T. Ranger, 101–164. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Carreira, P., and A. S. Lopes. 2021. “Drivers of academic pathways in higher education: Traditional vs. non-traditional students.” Studies in Higher Education 46 (7): 1340–1355.

- Christie, H., P. Barron, and N. D’Annunzio-Green. 2013. “Direct Entrants in Transition: Becoming Independent Learners.” Studies in Higher Education 38 (4): 623–637. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.588326

- Collini, S. 2012. What are Universities For? London: Penguin.

- Collins, A., F. Azmat, and R. Rentschler. 2019. “‘Bringing Everyone on the Same Journey’: Revisiting Inclusion in Higher Education.” Studies in Higher Education 44 (8): 1475–1487. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1450852

- Collison, P. 1956. “The Qualifications of Academics.” Universities Quarterly 10 (3): 273–282.

- Elton, L. R. B., and D. M. Laurillard. 1979. “Trends in Research on Student Learning.” Studies in Higher Education 4 (1): 87–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075077912331377131

- Erickson, M., P. Hanna, and C. Walker. 2021. “The UK Higher Education Senior Management Survey: A Statactivist Response to Managerialist Governance.” Studies in Higher Education 46 (11): 2134–2151. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1712693.

- Eustace, R. 1987. “The English Ideal of University Governance: A Missing Rationale and Some Implications.” Studies in Higher Education 12 (1): 7–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075078712331378240

- Finnegan, R. 1991. “Tradition, but What Tradition, and Tradition for Whom?” Oral Tradition 6: 104–125.

- Frank, J., N. Gowar, and M. Naef. 2019. English Universities in Crisis: Markets Without Competition. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

- Graham, H. D., and N. Diamond. 2004. The Rise of the American Research Universities: Elites and Challengers in the Postwar Era. Baltimore: John Hopkins Press.

- Gravett, K., and N. E. Winstone. 2021. “Storying Students’ Becomings into and Through Higher Education.” Studies in Higher Education 46 (8): 1578–1589. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1695112

- Halsey, A. H. 1992. Decline of Donnish Dominion: The British Academic Professions in the Twentieth Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Halsey, A. H., and M. A. Trow. 1971. The British Academics. London: Faber & Faber.

- Harding, R. D. 1980. “Computer Assisted Learning in Higher Education.” Studies in Higher Education 5 (1): 101–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075078012331377376

- Harries-Jenkins, G. 1979. “The Management of Higher Education.” Studies in Higher Education 4 (1): 113–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075077912331377151

- Hatt, S., A. Hannan, A. Baxter, and N. Harrison. 2005. “Opportunity Knocks? The Impact of Bursary Schemes on Students from Low-Income Backgrounds.” Studies in Higher Education 30 (4): 373–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070500160038

- HESA (Higher Education Statistics Agency). 2022. “HE Academic Staff (Excluding Atypicals) by HE Provider, Highest Qualification Held, Mode of Employment and Academic Year: Academic Years 2014/15 to 2020/21.” https://www.hesa.ac.uk/data-and-analysis/staff/working-in-he#acempfun.

- Hobsbawm, E., and T. Ranger, eds. 1983. The Invention of Tradition. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Huang, Y.-T., H. Liu, and L. Huang. 2021. “How Transformational and Contingent Reward Leaderships Influence University Faculty’s Organizational Commitment: The Mediating Effect of Psychological Empowerment.” Studies in Higher Education 46 (11): 2473–2490. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1723534

- Jarratt, A. 1985. A Report of the Steering Committee for Efficiency Studies in Universities. London: Committee of Vice-Chancellors and Principals.

- Johnston, S. 1995. “Building a Sense of Community in a Research Master’s Course.” Studies in Higher Education 20 (3): 279–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079512331381555

- Kolsaker, A. 2008. “Academic Professionalism in the Managerialist Era: A Study of English Universities.” Studies in Higher Education 33 (5): 513–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070802372885

- Kyvik, S., and D. W. Aksnes. 2015. “Explaining the Increase in Publication Productivity Among Academic Staff: A Generational Perspective.” Studies in Higher Education 40 (8): 1438–1453. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1060711

- Lilles, A., and K. Rõigas. 2017. “How Higher Education Institutions Contribute to the Growth in Regions of Europe?” Studies in Higher Education 42 (1): 65–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1034264

- Lowe, R. A., and R. Knight. 1982. “Building the Ivory Tower: The Social Functions of Late Nineteenth Century Collegiate Architecture.” Studies in Higher Education 7 (2): 81–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075078212331379171

- Lueddeke, G. R. 2003. “Professionalising Teaching Practice in Higher Education: A Study of Disciplinary Variation and ‘Teaching-Scholarship’.” Studies in Higher Education 28 (2): 213–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/0307507032000058082.

- Meeuwisse, M., Severiens, S.E. and M. Ph. Born. 2010. “Reasons for Withdrawal from Higher Vocational Education. A Comparison of Ethnic Minority and Majority Non-Completers.” Studies in Higher Education 35 (1): 93–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070902906780

- Meyer, J. W., and B. Rowan. 1977. “Institutionalized Organizations: Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony.” American Journal of Sociology 83 (2): 340–363. https://doi.org/10.1086/226550

- Moberly, W. 1949. The Crisis in the University. London: SCM Press.

- Moodie, G. C. 1976. “Authority, Charters and the Survival of Academic Rule.” Studies in Higher Education 1 (2): 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075077612331376679

- Moreau, M.-P., and C. Leathwood. 2006. “Balancing Paid Work and Studies: Working (-Class) Students in Higher Education.” Studies in Higher Education 31 (1): 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070500340135

- Murray, N. 2013. “Widening Participation and English Language Proficiency: A Convergence with Implications for Assessment Practices in Higher Education.” Studies in Higher Education 38 (2): 299–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.580838.

- Nadolny, A., and S. Ryan. 2015. “McUniversities Revisited: A Comparison of University and McDonald’s Casual Employee Experiences in Australia.” Studies in Higher Education 40 (1): 142–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2013.818642

- Newlands, D., and A. McLean. 1996. “The Potential of Live Teacher Supported Distance Learning: A Case-Study of the Use of Audio Conferencing at the University of Aberdeen.” Studies in Higher Education 21 (3): 285–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079612331381221.

- Nguyen, H. T. L., and B. Van Gramberg. 2018. “University Strategic Research Planning: A Key to Reforming University Research in Vietnam?” Studies in Higher Education 43 (12): 2130–2147. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1313218

- Niblett, W. R. 1981. “Robbins Revisited.” Studies in Higher Education 6 (1): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075078112331379479

- Niblett, W. R. 1983. “Where we are Now.” Studies in Higher Education 8 (2): 105–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075078312331378964

- Palmer, M., R. de Kervenoael, and D. Jacob. 2018. “Temporary Institutional Breakdowns: The Work of University Traditions in the Consumption of Innovative Textbooks.” Studies in Higher Education 43 (12): 2176–2193. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1324840

- Perkin, H. 1976. “Mass Higher Education and the Elitist Tradition: The English Experience.” Western European Education 8 (1–2): 11–35. https://doi.org/10.2753/EUE1056-493408010211

- Price, C., and M. Walker. 2021. “Improving the Accessibility of Foundation Statistics for Undergraduate Business and Management Students Using a Flipped Classroom.” Studies in Higher Education 46 (2): 245–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1628204

- Pronay, N. 1979. “Towards Independence in Learning History: The Potential of Video Cassette Technology for Curricular Innovation.” Studies in Higher Education 4 (1): 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075077912331377071

- Rip, A. 1979. “The Social Context of ‘Science, Technology and Society’s Courses.” Studies in Higher Education 4 (1): 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075077912331377061.

- Rossi, F. 2010. “Massification, Competition and Organizational Diversity in Higher Education: Evidence from Italy.” Studies in Higher Education 35 (3): 277–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070903050539

- Scheffler, S. 2010. “The Normativity of Tradition.” In Equality and Tradition: Questions of Value in Moral and Political Theory, edited by S. Scheffler, 286–311. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Shils, E. 1981. Tradition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Silva, De. 2016. “Academic entrepreneurship and traditional academic duties: synergy or rivalry.” Studies in higher education 41 (12): 2169–2183.

- Simons, M., and J. Elen. 2007. “The ‘Research–Teaching Nexus’ and ‘Education Through Research’: An Exploration of Ambivalences.” Studies in Higher Education 32 (5): 617–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070701573781

- Strengers, Y. A.-A. 2014. “Interdisciplinarity and Industry Collaboration in Doctoral Candidature: Tensions Within and Between Discourses.” Studies in Higher Education 39 (4): 546–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2012.709498.

- Sutphen, M., T. D. Solbrekke, and C. Sugrue. 2019. “Toward Articulating an Academic Praxis by Interrogating University Strategic Plans.” Studies in Higher Education 44 (8): 1400–1412. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1440384

- Tasker, M., and D. Packham. 1993. “Industry and Higher Education: A Question of Values.” Studies in Higher Education 18 (2): 127–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079312331382319

- Taulke-Johnson, R. 2010. “Queer Decisions? Gay Male Students’ University Choices.” Studies in Higher Education 35 (3): 247–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070903015755.

- Taylor, A. 1977. “Clinical Legal Education.” Studies in Higher Education 2 (2): 137–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075077712331376443

- Thiessen, E. J. 1989. “R. S. Peters on Liberal Education – A Reconstruction.” Interchange 20 (4): 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01807372.

- Tight, M. 1994. “What Crisis? Rhetoric and Reality in Higher Education.” British Journal of Educational Studies 42 (4): 363–374. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.1994.9974009.

- Trow, M. 1976. “The American Academic Department as a Context for Learning.” Studies in Higher Education 1 (1): 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075077612331376813

- Trow, M. 1989. “American Higher Education—Past, Present and Future.” Studies in Higher Education 14 (1): 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075078912331377582

- Trowler, P. 1997. “Beyond the Robbins Trap: Reconceptualising Academic Responses to Change in Higher Education (or … Quiet Flows the Don?).” Studies in Higher Education 22 (3): 301–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079712331380916

- Truscot, B. 1943. Red Brick University. London: Faber & Faber.

- Tynjälä, P. 1998. “Traditional Studying for Examination Versus Constructivist Learning Tasks: Do Learning Outcomes Differ?” Studies in Higher Education 23 (2): 173–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079812331380374

- UNESCO. 2019. Women in Science. Fact Sheet No. 55, FS/2019/SCI/55. Paris: UNESCO.

- van Schalkwyk, F. 2021. “Reflections on the Public University Sector and the Covid-19 Pandemic in South Africa.” Studies in Higher Education 46 (1): 44–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1859682

- Wallerstein, I., and P. Starr, eds. 1971. The University Crisis Reader: The Liberal University Under Attack. New York: Random House.

- Wang, C., X. Zhang, and M. Yao. 2019. “Enhancing Chinese College Students’ Transfer of Learning Through Service-Learning.” Studies in Higher Education 44 (8): 1316–1331. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1435635

- Weil, S. W. 1986. “Non-Traditional Learners Within Traditional Higher Education Institutions: Discovery and Disappointment.” Studies in Higher Education 11 (3): 219–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.1986.10721160

- Wentworth, K. K., S. J. Behson, and C. L. Kelley. 2020. “Implementing a New Student Evaluation of Teaching System Using the Kotter Change Model.” Studies in Higher Education 45 (3): 511–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1544234

- Woodfield, R. 2011. “Age and first destination employment from UK universities: are mature students disadvantaged.” Studies in Higher Education 36 (4): 409–425.

- Yang, B., and C. Huang. 2021. “Turn Crisis Into Opportunity in Response to COVID-19: Experience from a Chinese University and Future Prospects.” Studies in Higher Education 46 (1): 121–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1859687

- Zepke, N., L. Leach, and P. Butler. 2011. “Non-Institutional Influences and Student Perceptions of Success.” Studies in Higher Education 36 (2): 227–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070903545074.