Abstract

The present study was carried out to investigate the epidemiology and lesions of avian pox in captive peafowl chicks. Overall values of morbidity, mortality and case fatality were 45.2%, 27.1% and 60.0%, respectively. The chicks of 9 to 12 weeks of age showed a significantly (P<0.001) higher prevalence rate than other age groups. The morbidity and mortality due to avian pox in peafowl chicks was significantly (P<0.001) reduced when kept in mosquito-proof cages and hatched under broody chicken hens. Morbidity due to poxvirus infection on the peafowl farm was 82%, 26% and 12% in successive years. This reduction might have been the result of the introduction of mosquito-proof nets after year 1, although this was not the subject of a controlled experiment. All of the peafowl chicks suffering from dry pox showed pustular and nodular lesions on eye lids, beak, legs and toes. Distribution of lesions in different body parts varied significantly (P<0.023). Lesion diameters were less than 1 cm (59.73%), 1 to 2 cm (23.75%) and more than 2 cm (16.87%). Histopathological studies revealed extensive proliferation of subdermal connective tissue and infiltration of heterophils and macrophages. The keratinocytes showed degenerative changes in the form of cytoplasmic vacuolation, ballooning and hyper-chromatic nuclei. Eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions (Bollinger bodies) in keratinocytes were consistently present. It was concluded that avian pox rendered high morbidity, mortality and case fatality in peafowl chicks.

Introduction

The familiar and universally known peafowl (Pavo cristatus), a native to the Indian subcontinent (Kannan & James, Citation1998), is commonly kept as a pet and bred in captivity across many countries of North America, Asia and Europe (Johnson, Citation2008), although some peafowl live in wild or semi-wild environments (Anonymous, Citation2007). Like other birds, peafowl are susceptible to a number of pathogens leading to variety of diseases (Hollamby et al., Citation2003). In Pakistan, peafowl are mostly raised as pets in small or large aviaries and marketed in petbird shops. Peafowl raised in such conditions are kept on poor quality feed, not properly vaccinated and are exposed to natural pathogens leading to frequent nutritional, viral, bacterial and parasitic diseases.

Among the viral diseases, avian pox is a slow-spreading, infectious and contagious disease caused by a family of viruses collectively known as avipoxviruses (Tripathy & Reed, Citation2003). More than 60 species of free-living birds representing 20 families are known to contact the infection, like eagles (Hernández et al., Citation2001), mourning dove (Mete et al., Citation2001; Pledger, Citation2005), mynahs (Hsieh et al., Citation2005), starlings (Marsha & Richard, Citation1976), peafowl (Al-Falluji et al., Citation1979), short-toed larks (Smits et al., Citation2005), partridges (Buenestado et al., Citation2004) and other wild birds (Reed & Schrader, Citation1989). Outbreaks of avian pox in birds have been reported in many countries (Bolte et al., Citation1999; Buenestado et al., Citation2004).

Pox infection usually occurs through the mechanical transmission of the virus to injured skin and also the bite of mosquitoes or mites (Tripathy, Citation1991). Despite the variety of hosts, avian poxvirus infection is manifest either cutaneously or diptheritically, and both forms of the disease may occur in the same bird (Fallavena et al., Citation1993). In the cutaneous form, the proliferative lesions are primarily confined to featherless areas of skin; while in the more lethal diphtheritic form, the lesions may be found in the upper digestive and respiratory tracts (Tripathy et al., Citation2000). In the mild cutaneous form of pox disease, flock mortality is usually low, but it may be high when the infection is of a generalized or diphtheritic form and also when the flock is affected by a secondary infection, usually in poor environmental conditions (Gortázar et al., Citation2002).

Spontaneous cases of pox infection have been reported in different wild birds (Mete et al., Citation2001; Hsieh et al., Citation2005). In canaries, pox can cause mortality as high as 80 to 100% (Tripathy & Reed, Citation2003). In free-living galliformes, morbidity rates due to avian pox ranged from 2% to 54% (Davidson et al., Citation1985) and mortality rates were as low as 0.6% to 1.2% (Davidson et al., Citation1980). However, morbidity, mortality and case fatality in peafowl chicks due to avian pox has not been reported in the literature. To our knowledge, the present study is the first report describing pathology and epidemiological parameters of pox infection in captive peafowl chicks.

Materials and Methods

Birds and management

The study was carried out on 354 peafowl chicks belonging to five flocks maintained at private aviaries. These birds were divided into four age groups (1 to 4 weeks old, 5 to 8 weeks old, 9 to 12 weeks old, and older than 12 weeks).

Faisalabad, the third biggest city of Pakistan, has many privately owned zoo parks. Peafowl are invariably maintained by all of these zoo parks. There is also a public wildlife park (Guttwala Wildlife Parks and Breeding Farms, Fasialabad) maintaining about 200 peafowl. Other than these places, two to five pairs of peafowl are kept as pet birds by many families in the town and its suburbs. It is estimated that more than 2000 peafowl are kept as ornamental birds in the city. Peahens usually lay eggs during late winter until mid-summer. These are put in incubators or under broody turkey/chicken hens for hatching.

Chicks after hatching were monitored daily for the presence of signs of any clinical ailment up to 24 weeks of age. Morbidity and mortality percentages—first in each flock, then overall—were calculated by dividing the number of chicks showing pox lesions and chicks that died by the total number of chicks, and multiplying by 100, respectively. The number of chicks that died were divided by the number of morbid chicks, and then multiplied by 100 to calculate the case fatality (%). Morbidity, mortality and case fatality percentages in relation to age of the birds and total number of chicks at risk were also calculated.

Peafowl farm study plan

A peafowl farm was monitored for 3 years consecutively. The number of chicks on this farm during Year 1, Year 2 and Year 3 were 104, 116 and 94, respectively. For the first year, eggs were hatched under broody turkeys, and chicks were kept in open sheds. High morbidity and mortality in these chicks due to avian pox was assumed to be due to mosquito bites. In the second year, mosquito-proof sift/net was applied to cages and the chicks were thus protected from mosquitoes from the first day of age. During the third year, eggs were hatched under broody chicken hens.

Gross and histopathological lesions

The morbid birds were examined for gross lesions on various parts of the body. The type of lesion with their length, width and diameter was recorded. Eighty-seven birds soon after death were subjected to complete necropsy. Samples of morbid tissues were preserved in 10% neutral buffered formalin and were processed by a routine paraffin embedding technique. Tissue sections of 4 to 6 µm thickness were stained with haematoxylin and eosin for microscopic examination.

Statistical analysis

Morbidity, mortality and case fatality in peafowl chicks were calculated. Data regarding flock size, age, distribution of lesions on various parts of the body and lesion measurement were subjected to statistical analysis using the chi-square test. To see the effect of the application of mosquito-proof sift/net to cages, the data related to morbidity, mortality and case fatality in peafowl chicks at a peafowl farm were collected consecutively for 3 years and were analysed using the chi-square test at a significance level of 0.05.

Results

Morbidity, mortality and case fatality

In the present study, overall morbidity, mortality and case fatality due to avian pox in peafowl chicks was 45.2%, 27.1% and 60.0%, respectively (). Concurrent occurrence of other clinical diseases/infections with avian pox in peafowl chicks was not observed. The occurrence of lesions showed a significant difference in relation to age (P<0.001). Peafowl chicks aged 9 to 12 weeks showed the highest morbidity and mortality due to avian pox, followed by the 5 to 8 weeks old age group (). Case fatality in relation to age differed non-significantly.

Table 1. Morbidity, mortality and case fatality in peafowl chicks suffering from avian pox

Table 2. Morbidity, mortality and case fatality in relation to age in peafowl chicks suffering from avian pox

Peafowl farm study

During the first year, morbidity due to avian pox was 81.7% (). In the next year, keeping the chicks from the first day in mosquito-proof cages resulted in a lower morbidity of 25.8% compared with the previous year. In Year 3, hatching of peafowl eggs was carried out under broody chicken hens, curtailing the morbidity to 11.7%. A significant difference was present in the morbidity values of the three years (χ2=46.303, P<0.001). Similarly, mortality of 60.5% in the first year fell to 13.7% in the second year while in Year 3 it was 5.3%. Data analysis revealed that mortality (χ2=49.425, P<0.001) also varied significantly within the 3 years, whereas case fatality (P>0.487) did not ().

Figure 1. Morbidity, mortality and case fatality in peafowl chicks suffering from avian pox consecutively for 3 years on the same farm. Morbidity (χ2=46.303, P < 0.001, degrees of freedom = 2) and mortality (χ2=49.425, P < 0.001, degrees of freedom = 2) varied significantly, whereas case fatality (χ2= 1.439, P > 0.487, degrees of freedom = 2) did not between the three years at the farm.

Gross lesions

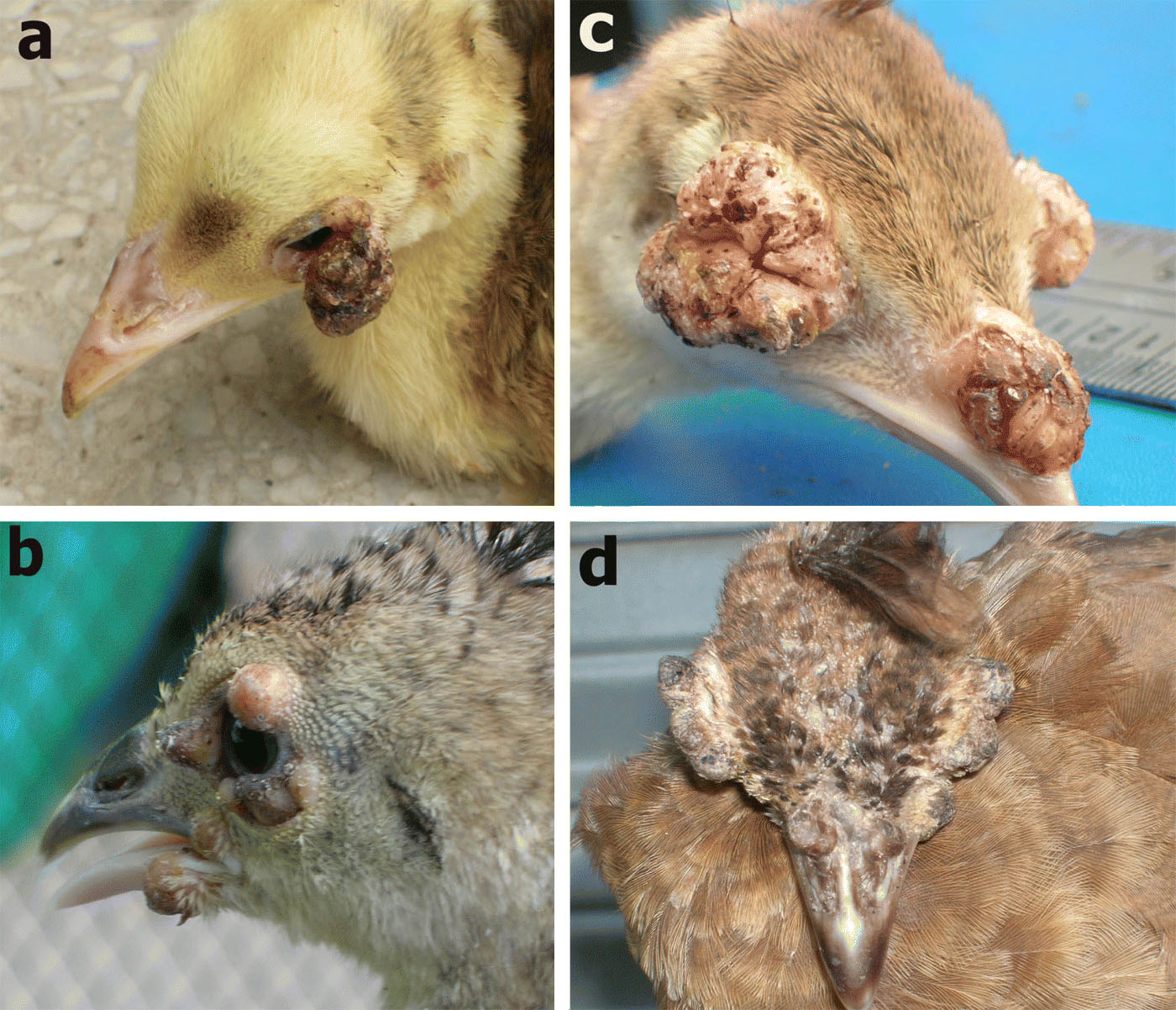

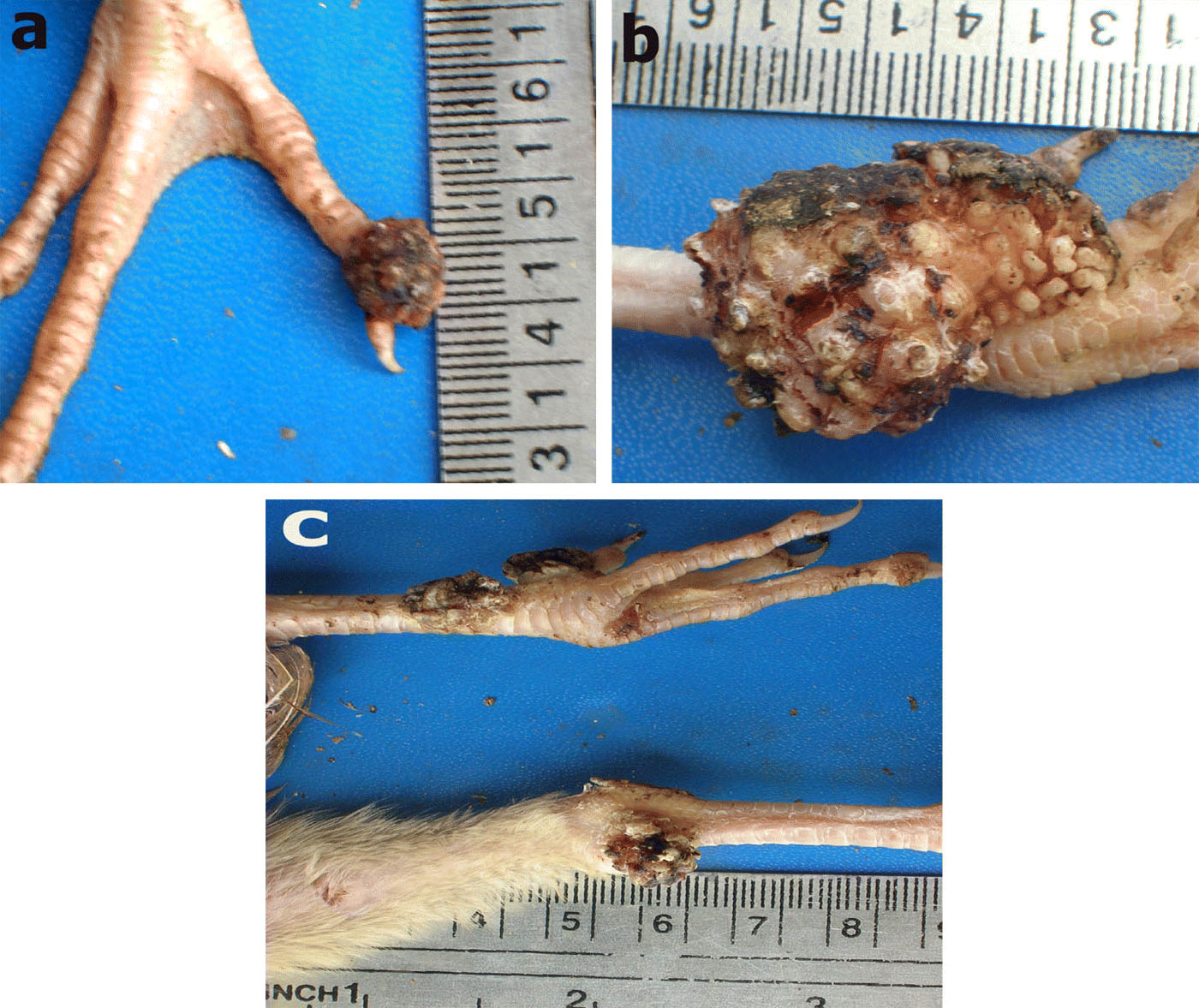

All of the peafowl chicks showed dry pox lesions on the external body surfaces, and no internal lesions could be observed in necropsied birds. Mostly the lesions were in the form of papules, pustules or scabs while single or multiple nodular growths were also recorded. Sometimes cauliflower-like growth was also observed. Lesions were present on the eye lids, beak (), legs and toes (). Eye lid and beak lesions showed significantly (P<0.023) high (18.12%) frequency as compared with lesions on other body parts ().

Figure 2. Gross lesions of avian pox in peafowl chicks on the eye and beak. 2a: well developed lesions on the eye lid, eye is partially open. 2b: multiple nodular growth around the eye and also on the beak. 2c: note the cauliflower-like growth on the eye and beak. 2d: scar formation of the lesions on and around the eye and beak, still eyes are closed due to lesions.

Figure 3. Gross lesions of avian pox in peafowl chicks on the leg and toe. 3a: a nodular growth on one of the toes. 3b: leg lesions were much larger in some of the peafowl chicks, lesion measured 3.25 cm (length) x 2 cm (width). 3c: both of the legs were having variably sized lesions on various parts (i.e. knee joint, shaft, fingers, toe, etc.).

Table 3. Topographic distribution of avian pox lesions in peafowl chicks

Data analysis revealed that the size of the lesions differed significantly (P<0.001). The size of lesions ranged from 0.75 to 3.25 cm, and was less than 1 cm, 1 to 2 cm, and more than 2 cm in 59.4%, 23.8% and 16.9%, respectively, of all lesions examined ().

Table 4. Size-wise distribution of avian pox lesions in peafowl chicks

Histopathology

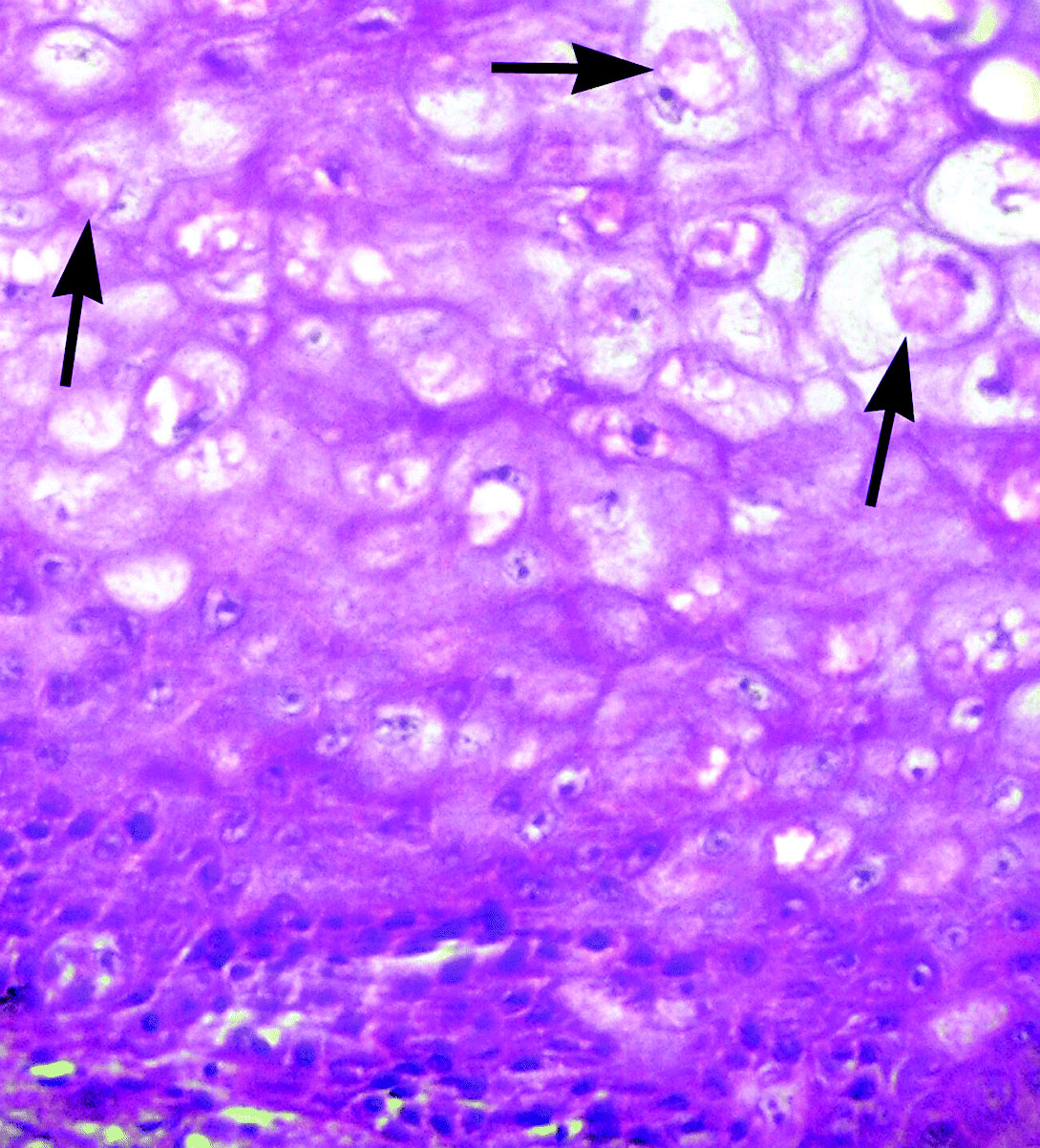

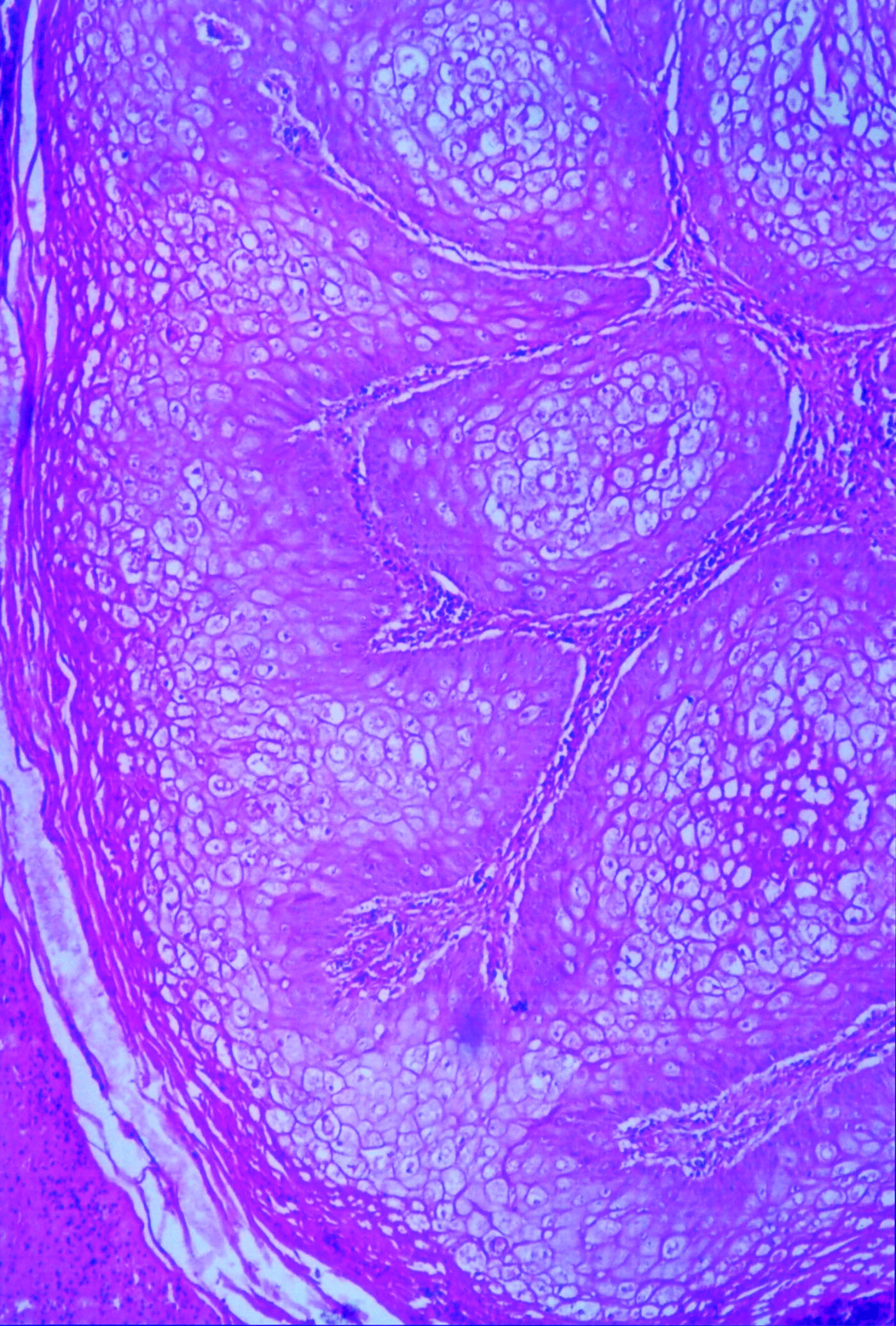

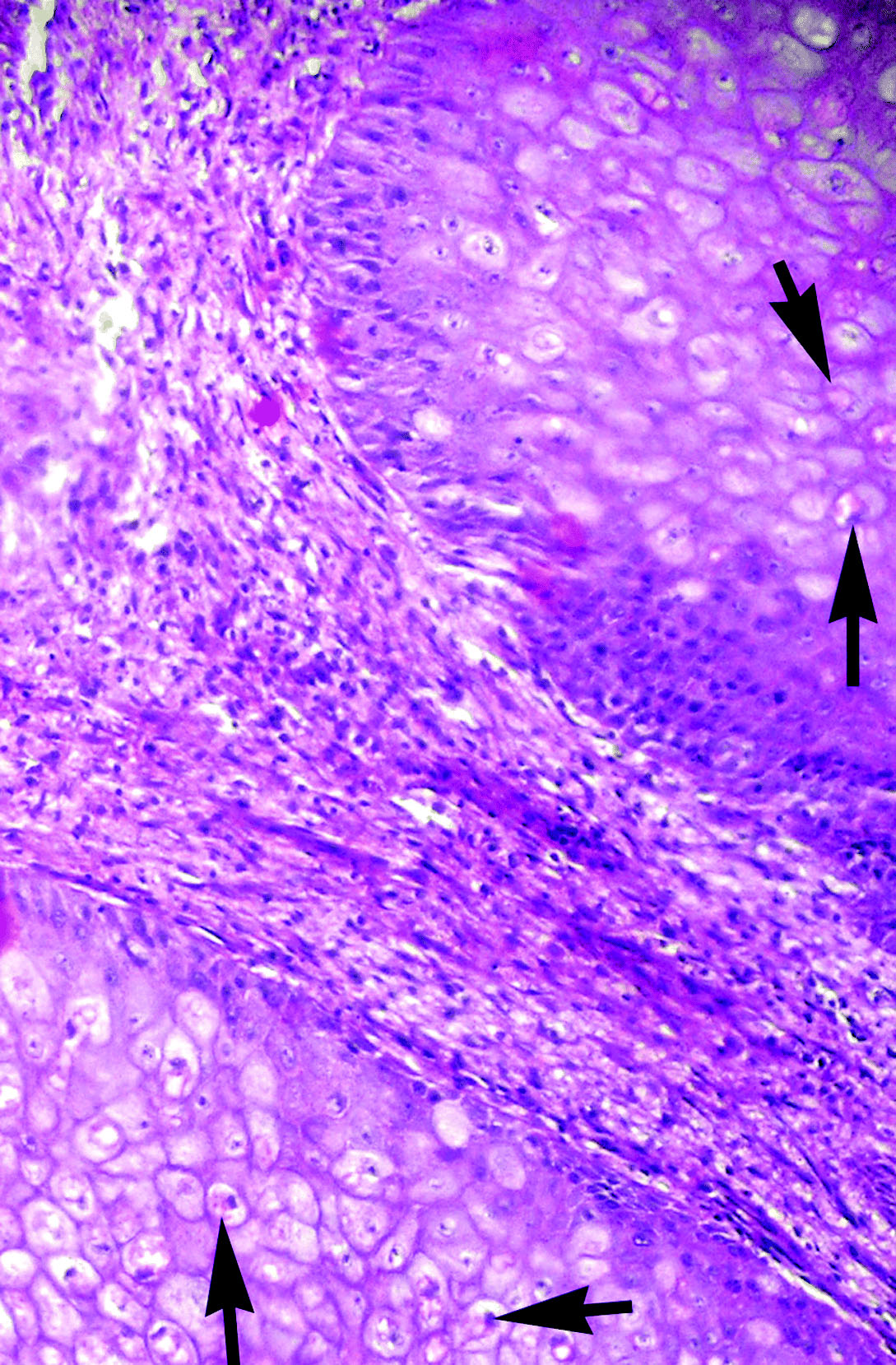

On histological examination of pox lesions, the keratin layer of the epidermis was intact. There was extensive proliferation of subdermal connective tissue, which was also infiltrated with polymorph mononuclear cells and macrophages (). The keratinocytes were rounded and swollen like balloons. Swollen keratinocytes had enlarged pleomorphic and hyper-chromatic nuclei (). Many keratinocytes also showed cytoplasmic vacuolation and eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions (Bollinger bodies), pushing the nuclei to a side ().

Figure 4. Intact keratinized surface, excessive proliferation of fibrous connective tissue, lobular pattern and infiltration of heterophils and macrophages in peafowl chick suffering from avian pox. Haematoxylin and eosin. Magnification x40.

Figure 5. Extensive proliferation of fibrous connective tissue, rounded and swollen keratinocytes with pleomorphic and hyperchromatic nucleus and eosinophilic intracytoplasmic (Bollinger bodies) inclusion bodies (arrows) in peafowl chick suffered from avian pox. Haematoxylin and eosin. Magnification x100.

Discussion

In the present study, morbidity in peafowl chicks due to avian pox ranged from 25.8% to 100% with an average of 45.2%, and mortality ranged from 5.3% to 60.5% with an average of 27.1%. Case fatality was 60%. Morbidity, mortality and fatality in peafowl chicks due to avian pox have not been reported in the published literature. Consequently results of the present study could not be compared. However, morbidity and mortality rates due to avian pox in free-living galliformes have been reported to be 2% to 54% (Davidson et al., Citation1985) and 0.6 to 1.2% (Davidson et al., Citation1980), respectively. Higher mortality rates (80% to 100%) due to pox have been reported in canaries and finches (Tripathy & Reed, Citation2003), which might be due to the viraemic or systemic form of pox involving cutaneous, respiratory, digestive and ocular systems. According to Pledger (Citation2005), mortality is generally low in the cutaneous form of pox if eating and respiration are not severely affected. However, in the present study, eye lid lesions were in many cases large enough to cover whole the eye, rendering the birds unable to look and eat feed. This might have been a reason for the higher mortality.

Avian poxvirus is incapable of penetrating the intact epidermis but requires broken skin for transmission (Tripathy & Reed, Citation2003), which is carried out by the bites of mosquitoes or other blood-sucking arthropods (Gerlach, Citation1994). It is believed that mosquitoes can harbour the virus for a month or even more (Ritchie, Citation1995). Applying mosquito-proof sieve to cages curtailed morbidity due to pox from 81.7% to 25.8% () in the present study, supporting the hypothesis that mosquitoes might have been responsible for the transmission of the disease. In Pakistan, the egg-laying season of peafowl extends from late winter to mid-summer, and the mosquito population is also very high during this period as it is the breeding season for mosquitoes (Mukhtar et al., Citation2003). Occurrence of lesions on the un-feathered areas of the body, such as the face and legs, could be the reflection of the usual feeding at these sites by such arthropods (Hernández et al., Citation2001).

Hatching of peafowl eggs under broody turkeys was another factor recorded to enhance the incidence of pox in peafowl chicks as its elimination also helped to curtail morbidity significantly in the present study (). Turkeys used for hatching could have been the carriers of the virus and a source of infection for young chicks. However, this factor needs further investigation for confirmation. In the present study, maximum morbidity due to pox was observed in 9-week-old to 12-week-old chicks. Younger individuals were more vulnerable to avian pox than the adult birds, as the latter could have developed specific immunity (Buenestado et al., Citation2004).

In the present study, the cutaneous form of the disease was observed in all of the affected peafowl chicks, and lesions developed on unfeathered parts of the body mostly upon the face, eye lids, base of beak and legs. The published literature shows that the most common cutaneous or dry pox involves the unfeathered parts of the body (Pledger, Citation2005). The pathology of pox infection is considered similar regardless of the strain of poxvirus or species of bird infected (Smits et al., Citation2005). In the present study, affected peafowl chicks exhibited nodular and wart-like projections on various parts of the body—and in some cases there were even proliferative lesions on the shaft of the legs and eyes. Nodular (Smits et al., Citation2005) and proliferative skin lesions (Buenestado et al., Citation2004) in various avian pox-affected birds have been reported.

Histopathological alterations observed in the affected chicks in present study consistently comprised of degeneration and necrosis of keratinocyte and hypertrophy and hyperplasia of epithelial cells in lower layers of epidermis. Eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies (Bollinger bodies) in keratinocytes were consistently present. Similar results have also been reported in owls (Deem et al., Citation1997), mourning dove (Pledger, Citation2005) and chickens (Tripathy & Reed, Citation2003). Light microscopic evaluation of pox-affected tissues exhibits the presence of the typical large, solid or ring-like eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions known as Bollinger bodies (Smits et al., Citation2005). The appearance of eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies in keratinocytes is considered confirmatory (Randall & Reece, Citation1997; Pledger, Citation2005).

References

- Al-Falluji , M.M. , Tantawi , H.H. , Al-Bana , A. and Sheikhly , S. 1979 . Pox infection among captive peacocks . Journal of Wildlife Diseases , 15 : 597 – 600 .

- Anonymous . 2007 . Common (Indian) peafowl . Available online at http://www.rollinghillswildlife.com/animals/p/peafowl/ ( accessed 23 July 2008 ).

- Bolte , A.L. , Meurer , J. and Kaleta , E.F. 1999 . Avian host spectrum of avianpoxviruses . Avian Pathology , 28 : 415 – 432 .

- Buenestado , F. , Gortázar , C. , Millán , J. , Höfle , U. and Villafuerte , R. 2004 . Descriptive study of an avian pox outbreak in wild red-legged partridges (Alectoris rufa) in Spain . Epidemiology and Infection , 132 : 369 – 374 .

- Davidson , W.R. , Kellogg , F.E. and Doster , G.L. 1980 . An epornitic of avian pox in wild bobwhite quail . Journal of Wildlife Diseases , 16 : 293 – 298 .

- Davidson , W.R. , Nettles , V.F. , Couvillion , C.E. and Howerth , E.W. 1985 . Diseases diagnosed in wild turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo) of the southeastern United States . Journal of Wildlife Diseases , 21 : 386 – 390 .

- Deem , S.L. , Heard , D.J. and Fox , J.H. 1997 . Avian pox in eastern screech owls and barred owls from Florida . Journal of Wildlife Diseases , 33 : 323 – 327 .

- Fallavena , L.C.B. , Rodrigues , N.C. , Scheufler , W. , Martins , N.R.S. , Braga , A.C. , Salle , C.T.P. and Moraes , H.L.S. 1993 . Atypical fowlpox in broiler chickens in southern Brazil . The Veterinary Record , 132 : 635

- Gerlach , H. 1994 . “ Viruses ” . In Avian Medicine: Principles and Applications , Edited by: Ritchie , B.W. , Harrison , G.J. and Harrison , L.J. 862 – 948 . Lake Worth , FL : Winger's Publications .

- Gortázar , C. , Millán , J. , Höfle , U. , Buenestado , F.J. , Villafuerte , R. and Kaleta , E.F. 2002 . Pathology of avian pox in wild red-legged partridges (Alectoris rufa) in Spain . Annals of New York Academy of Sciences , 969 : 354 – 357 .

- Hernández , M. , Sánchez , C. , Galka , M.E. , Dominguez , L. , Goyache , J. , Oria , J. and Pizarro , M. 2001 . Avian pox infection in Spanish Imperial eagles (Aquila adalberti) . Avian Pathology , 30 : 91 – 97 .

- Hollamby , S. , Sikarskie , J.G. and Stuht , J. 2003 . Survey of peafowl (Pavo cristatus) for potential pathogens to three Michigan zoos . Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine , 34 : 375 – 379 .

- Hsieh , Y.C. , Chen , S.H. , Wang , C.W. , Lee , Y.F. , Chung , W.C. , Tsai , M.C. , Chang , T.C. , Lien , Y.Y. and Tsai , S.S. 2005 . Unusual pox lesions found in Chinese jungle mynahs (Acridotheres cristatellus) . Avian Pathology , 34 : 415 – 417 .

- Johnson , L. 2008 . The peacock pages: all about peacock keeping . Available online at http://www.gamebird.com/peacock.html ( accessed 23 July 2008 ).

- Kannan , R. & James , D.A. 1998 . Common peafowl (Pavo cristatus) . In A. Poole Birds of North America Online . Ithaca , NY : Cornell Lab of Ornithology . Available online at http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/377 ( accessed 23 July 2008 ).

- Marsha , L. and Richard , M.K. 1976 . Transmission of avian pox from starlings to rothchilds nynahs . Journal of Wildlife Diseases , 12 : 353 – 356 .

- Mete , A. , Borst , G.H.A. and Dorrestein , G.M. 2001 . Atypical poxvirus lesions in two Galapagos doves (Nesopelia g. alapagoensis) . Avian Pathology , 30 : 159 – 162 .

- Mukhtar , M. , Herrel , N. , Amerasinghe , F.P. , Ensink , J. , van der Hoek , W. and Konradsen , J. 2003 . Role of wastewater irrigation in mosquito breeding in south Punjab, Pakistan . Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health , 34 : 72 – 80 .

- Pledger , A. 2005 . Avian pox virus infection in a mourning dove . Canadian Veterinary Journal , 46 : 1143 – 1145 .

- Randall , C.J. and Reece , R.L. 1997 . Color Atlas of Avian Histopathology , London : Mosby-Wolfe Publishing .

- Reed , W.M. and Schrader , D.L. 1989 . Pathogenicity and immunogenicity of Mynah pox virus in chickens and Bobwhite quail . Poultry Science , 68 : 631 – 638 .

- Ritchie , B.W. 1995 . Avian Viruses: Function and Control , 285 – 311 . Lake Worth , FL : Winger's Publishing .

- Smits , J.E. , Tella , J.L. , Carrete , M. , Serrano , D. and López , G. 2005 . An epizootic of avian pox in endemic short-toed larks (Calandrella rufescens) and Berthelot's pipits (Anthus berthelotti) in the Canary Islands, Spain . Veterinary Pathology , 42 : 59 – 65 .

- Tripathy , D.N. 1991 . Diseases of Poultry , Edited by: Calnek , B.W. , Barnes , H. , Beard , C.W. , Reid , W.M. and Yoder , H.W. 583 – 596 . Ames : Iowa State University Press .

- Tripathy , D.N. and Reed , W.M. 2003 . Diseases of Poultry , 11th edn , Edited by: Saif , Y.M. , Barnes , H.J. , Glisson , J.R. , Fadly , A.M. , Mc-Dougald , L.R. and Swayne , D.E. 253 – 269 . Ames : Iowa State University Press .

- Tripathy , D.N. , Schnitzlein , W.M. , Morris , P.J. , Janssen , D.L. , Zuba , J.K. , Massey , G. and Atkinson , C.T. 2000 . Characterization of poxviruses from forest birds in Hawaii . Journal of Wildlife Diseases , 36 : 225 – 230 .