Abstract

This paper explores how, in countries in the global south where sharp rises in indebtedness have accompanied the financialization of the economy, debt factors into other relationships and meanings in the life of the family and household. Using ethnographic material from South Africa, it explores local concepts of householding, obligation and saving (asking whether relations of commodified debt nullify those of longstanding social commitment), investigates how people convert between cash-based or short-term imperatives and moral or longer-term ones, and shows how barriers are sometimes erected between these separate spheres thus making them incommensurable. The paper challenges some accounts of the ‘financialization of daily life’ which imply a one-way, top-down intrusion by the market – with state backing – into people’s intimate relations, commitments and aspirations, and maintains that we need to explore the complicity of participants’ engagement with these processes rather than seeing them as imposed on unwilling victims.

‘Ons skuld tot ons vrek’, Mmagojane Sekwati once told me when I was doing my first fieldwork trip, three hours’ drive to the north-east of Johannesburg, in the 1980s. This means ‘We will be in debt until we die’. She used Afrikaans, although she was a native SePedi speaker, because she and her family had lived and worked as labour tenants on a white farm prior to being resettled in one of South Africa’s homelands. She was referring to a government agricultural scheme that was providing inputs to small-scale cultivators, deducting repayments from their yield after the harvest, but always leaving them owing more than they could repay. Additionally, they were paying off a table and chairs bought on hire purchase from a furniture retailer in the nearest town, in South Africa’s peculiar system of what has been called ‘credit apartheid’. These were not the family’s only experiences of long-term obligation. In a manner longstanding (and well documented) for black cultivator/pastoralists in the region, her household was embedded in an intricate set of staggered payments and reciprocal repayments that was initiated, by a kind of domino effect, when one of its members married. Despite the process of colonial dispossession that had thrown up this household on the margins of a capitalist economy, or perhaps because of such processes, gifts and counter-gifts of this kind were of crucial importance in tying her household to other families – but also in stretching its resources, sometimes to breaking point. But this kind of customary wealth flow and obligation was invisible to outsiders. Many accounts have seen the economy of South Africa as overwhelmingly capitalist; showing how, during the apartheid years, strong state regulation had prevailed and growth, where it occurred, involved the twin trajectories of ‘maize’ (Afrikaner capital) and ‘gold’ (its English counterpart) (Trapido, Citation1978). In the race to modernize farming in the former sector and transform it into large-scale agriculture, families that had once lived on white farms as semi-feudal labour tenants, like Mmagojane’s, had by the time of my fieldwork been cast aside.

Fast-forward 35 years, democracy has arrived, apartheid has come to an end, the economy has liberalized, and financialization has proceeded apace (Barchiesi, Citation2011; Makhulu, Citation2017; Marais, 2011, pp. 124–128, 132–139).Footnote1 I discovered in my most recent fieldwork, speaking to householders from similar backgrounds, both in urban and in rural settings, that these transitions have brought both the promise and to some degree the actuality of vastly improved circumstances and status. Policy analyst Ivor Chipkin (Citation2013) uses the term ‘middle classing’ to capture how this involves process rather than product, a journey rather than an arrival point. The likes of Mmagojane’s children have become civil servants – nurses, teachers, policemen, senior office-holders in government departments – or middle managers in companies and corporations. Many (but not all) people in this bracket, some (but not all) of whom have moved swiftly upwards from semi-literate backgrounds, are typically in debt to the tune of hundreds of thousands of rands. To bridge the gap between aspiration and its actualization, more of them need or want to borrow, and there is more money available for lending. Many have taken out bank loans, own several credit cards, hold store cards from an array of retailers, and are paying back a vehicle finance company alongside the furniture retailers of earlier times, as well as having borrowed from other lenders, both formal (legal) – so-called microlenders – and informal (illegal) mashonisas or loan sharks. Many also aspire to, even if they do not achieve, the goal of paying bridewealth and affording the mandatory white wedding that accompanies it. The phrase used to capture this conundrum, replacing ‘we owe until we die’, is ‘we are now working for mashonisa’. In place of an execution, it suggests a life sentence. Both statements seem to express profound resignation, even despair.

Moving beyond such resignation, and looking one generation further, the likes of Mmagojane’s grandchildren have a somewhat different experience of debt. A key expense for which their parents borrowed was to pay for their university fees. Many have acquired a higher education but they still owe money to the university and their degree certificates are being withheld. Recognizing that the promises of high status are hollow if they can only be acquired on the never-never, they have joined the #Feesmustfall movement that brought the university sector to its knees in 2015 and that demanded – and was granted, albeit in provisional form – some kind of debt relief. At last, it seems, people in this generation are overcoming the individualization and even self-blame that often accompanies getting into debt. The death sentence and the life sentence appear, here, to be commuted, or at least deferred.

Below I explore this three-generational debt shift, with its changing modalities of freedom and enslavement. I explore several issues. The first and more central one is: in understanding debt, how might we transcend the tendency to explore matters of economy by classifying exchanges on either side of the capitalist/non-capitalist divide and ultimately assuming that those on the capitalist side prevail? The second, through my conscious parodying of the title of Clara Han’s book Life and debt (Citation2012) set in Chile, draws attention to the conundrum of indebtedness across the global south, but – unlike her – asks about the newly indebted ‘middle classers’ in particular (Chipkin, Citation2013). If financialized capitalism is a driving force in the twenty-first century across a variety of southern settings, what implications does it have for the aspirations of such upwardly mobile people? Contrarily, and looking at the South African case in particular, how far must we understand local particularities at the level of state and household in order to fill in the picture? Finally I explore whether, in looking at this case of credit boom, there is some purchase in the Comaroffs’ (Citation2012) claim that the south can be viewed as a kind of experimental laboratory in which practices are tried out before they are exported to the north. All in all, the paper challenges some accounts of the ‘financialization of daily life’ which imply a one-way, top-down intrusion by the market, with state backing, into people’s intimate relations, commitments and aspirations, and maintains that we need to explore the complicity of participants’ engagement with these processes rather than seeing them as imposed on unwilling victims.

Contract/non-contract: Articulation again?

Life in debt in South Africa is not pure slavery. Instead, it has an ambivalent character. For the likes of Mmagojane's children, as Clara Han (Citation2012) found in Chile, access to credit allows people to live a life of consumerism and aspiration from which they were previously excluded. But they are aware that, since these things have been given to them on tick, theirs is a ‘loaned life’. The debt is necessary to actualize dreams of a better world in which harmonious relations with family members might be possible. But being unable to repay while creditors knock at the door is disabling and may even destroy those relationships. In these two cases and more broadly across the south (in others I will describe), the debt conundrum juxtaposes apparently unlike sets of values. Cherished and non-commodified family relations, on the one hand, both induce and are subject to the inexorable force of commodified payment-plus-interest on the other.

Parker Shipton in his book The nature of entrustment (Citation2007) maintains that the Luo of Kenya ‘are at times profit-seeking marketeers and at times reciprocators and redistributors’. This description of alternating modalities is one recent attempt to deal with a conceptual binary that has been of long standing. Capitalist or market-style relations on the one hand are counterposed against those which in substance and form are their opposite on the other. That is, the contract and what appears non-contractual are made to appear as opposites. Jane Guyer (Citation2004) has shown how a West African logic of economic activity dovetailed with – while also countermanding – a capitalist one. She describes a setting ‘where magical conceptions about money coexist with routine numeration rather than contradicting it’; speaks of multiplicity rather than binaries; and shows how the formalization and financialization of economic arrangements can be accompanied by their opposite, all held within the same frame but not subject to some dominant hegemonic force originating in the capitalist west. The way these authors enunciate the coexistence of rational calculation and reciprocity may seem to imply that people are free to choose which mode to switch to, and when. Their analyses have of course been praised for countering the determinism of Marxist accounts, prevalent in the 1960s, according to which modes of production were ‘articulated’ with each other. Writing in the first volume of Economy and Society, Harold Wolpe (Citation1972) famously enunciated his ‘cheap labour thesis’, showing how capitalism in South Africa relied for the reproduction of its workforce, and hence its profit, on the rural economy of African cultivator/pastoralists. Yet, analysing two phenomena as ‘articulated’ relies on being able to separate them to some extent. The material I will present shows, in contrast, a more inextricable entanglement between debt in its non-commodified and commodified versions: one that is more in line with Shipton’s and Guyer’s accounts, but that belies the easy-sounding switch from calculation to reciprocity which they describe. As I show in more detail elsewhere, their inextricable entanglement owes itself, in part, to the role of intermediaries and agents (James, Citation2016).

For the cultivator/pastoralists whose lands were later to become South Africa, debt was a feature of life before the introduction of capitalist relations. Long-term, enduring, and apparently non-marketized systems of obligation existed in the form of bridewealth payments. In the present day, the relation of such payments to that of market-style, interest-bearing debt can be coercive and exert extreme pressure. In one case I documented in 2012, a man attempting to position himself in the local solidarity economy by committing to bridewealth was only able to do so by incurring so much interest-bearing debt from a microlender that it threatened to undermine the very social arrangements which it was supposed to enhance. My earlier account showed how the positive character of aspirations to fulfil long-term social obligations, on the one hand, articulate uneasily with negative experiences of financialized arrangements – and being hounded by creditors and taking out further loans – on the other (James, Citation2014). But, while this conceptualization of the relationship – which is refracted through the particular southern African prism of marriage payments – has some truth, it still represents matters too starkly. One is still confronted by a stark binary – ‘mutuality is good, commodity is bad’.

Why have I had to rethink this? For one thing, because the proliferating dependencies of the wives for cattle system in its earlier incarnation could themselves constitute a form of slave-like entrapment. The networks of reciprocity, and the knock-on set of exchanges, which occurred between houses on the occasion of marriage, have been analysed – and recently reanalysed – by Adam Kuper (Citation1982, Citation2016). Each house, headed by one of several wives of a polygynist, became a nodal point for the accumulation and transfer of concrete wealth. Although wealth was reckoned and paid through cattle, marriage payments actually enabled a transfer of resources from the pastoral to the agricultural part of the house economy, since cattle given for a wife provided the wife-receiving household with female labour for the growing of grain. Each wife, once children were born, became the head of a separate cattle-owning house. Its cattle, once received in marriage, would be re-used when that family needed to transfer bridewealth for the marriage of its own son to a further house. But the system, if that is what it was, had inherent tensions. Debts were often recouped to deal with structural/demographic accidents rather than serving to weave together a Levi-Straussian web of connections. In part because being used for multiple purposes in this way, the value of cattle was inflated. Against this backdrop, missionary and anthropologist Henri Junod, in 1912, gave an account of hatred and bitterness between unpaid wife-givers and the unpaying wife-receivers against whom they were bringing civil suits in epidemic numbers. This was not necessarily because people wanted to cash in their cattle: much like house-buyers in a mortgage chain, the wife-giving house was waiting for cattle to use in respect of its own sons’ marriages. But the resulting arrangements were characterized by Junod as equating to virtual enslavement (Kuper, Citation2016). Long-term relationships, then, could be onerous. In this sense, non-capitalist exchanges and dependencies, essential in creating productive relationships, seem less different from their more recently emerging counterpart, commodity debt, than might have appeared the case.

But what does this modern commodity debt look like in practice? And what can we learn from comparing it with similar cases across the south?

Middle classing and debt across the south

The ambiguities of indebtedness for the Chilean poor have already been described. But equivalent ambiguities are true – even more trenchantly – for middle classers (Chipkin, Citation2013). The cases I will explore below – South Africa, Malawi (Anders, Citation2009) and India (Parry, Citation2012) – show striking similarities, suggesting that global conditions have imposed some universally shared characteristics upon newly indebted members of this category. The resulting picture shows qualities every bit as systemic as that of the wives for cattle arrangement already described. First, in a manner reminiscent of the nascent German bourgeoisie in the nineteenth century (and unlike their predominantly entrepreneurial counterparts in Britain – see Lentz, Citation2016) they mostly rely on salaries paid, directly or indirectly, by the state. These salaried forms of employment were, in the South African case, newly acquired through the changing racial composition of the civil service. In the case of Malawi, these positions were clung onto despite recent cuts to state spending, while in the Indian case they were held by employees in a public-sector steel plant. In these settings where class status is only recently acquired, or particularly vulnerable and tenuous, the imperative of status distinction described by Bourdieu (Citation1984) is accompanied by the imperative to offer support to those from whom one has become (newly) distinguished.

A second common factor is that the liberalization of the economy, in all three cases, has diminished or eradicated income sources for the neighbours or kinsmen of the upwardly mobile. Given that these ‘middle classers’ exist in a setting where liberalization has been accompanied by public sector reform, such that their own wider kin increasingly lack reliable forms of livelihood, their salaries are relied upon to do more than support just their immediate families. It is partly to ensure this that they borrow money and often become overindebted. Liberalization also means that such loans are much more readily available than they might have been a generation ago (Servet & Saiag, Citation2013). Not only is there ‘more money’ available, but moneylenders of all kinds have newly acquired a speedier and more reliable system of collateral: that of deducting repayments directly from the salaried income of debtors.

Let us look at each case in turn. In a paper on suicide by employees of the state-owned Bhilai steel plant in India by Johnny Parry (Citation2012), we are told that debts are mostly incurred by, and offered to, those who are threatened – or whose children are threatened – with downward mobility from a previous state of secure employment as the public sector downsizes. People cite addiction, womanizing and family tensions as reasons for the high suicide rate, but few analyses, says Parry, deal with the ‘causes of the causes’. Chief among these is indebtedness, to which ‘those with collateral’ – that is, secure jobs and salaries – are most vulnerable. The difficulties of staying on top are considerable, but these people are not simply running to stand still. Expectations are intensifying, even for those who do succeed in remaining as members of what he calls the labour aristocracy. They have aspirations beyond their reach, including maintaining their current status and meeting the ‘increasingly exacting standards’ – educational attainments and consumption patterns – that go with that status. Loans are taken out from a variety of lenders; co-operative societies, or loan sharks who lend money ‘against the security of their bank passbooks [or] ATM cards’, and from employers at the plant. ‘Loan repayments to the plant halve one’s take-home pay, and the creditor who has one’s passbook claims the rest in interest – 10% monthly’. In a few cases, however, where debts are not secured by these forms of collateral, creditors harass borrowers, and some suicides are alleged to have been prompted by this harassment alone. Their efforts – and the negative consequences – might be characterized as an intrinsic part of the new pressures to consume and to support kin that are entailed in ‘middle classing’, and their suicides as a sign that the struggles this process entails are too onerous to be borne.

The Malawian civil servants documented by Anders (Citation2009), in a setting where cuts and downsizing similarly prevail, likewise borrow from employers. Here, the key ‘distinctions’ are those between kin at different levels in the hierarchy, which are an important part of the problem. The structural adjustment of the 1980s brought the reform of the public sector, so that there were fewer jobs to go around. Inflation had also caused salaries to decline in real terms, and their recipients were increasingly using them to kick-start or underpin informal business ventures intended to supplement their formal incomes. Those with regular earnings found themselves relied upon to help their unemployed relatives. Partly to make this possible, they became reliant on loans from their employers, in the form of ‘advances’, at virtually no interest, often to the tune of two-thirds of their salary. Employers used a system of automatic deductions and thus bore no risk of default. Although the rates of interest were low, this did not lessen the fact that employees were increasingly living on future earnings. Here too, salaries served as collateral for the employers-turned-creditors. The ultimate aim was that of caring for kin, but the resulting relationship between depended-upon and dependent was often one of tension and strife rather than accord.

In South Africa, similar arrangements result in the claim that ‘the worker finds himself working for nothing’, or ‘for mashonisa’ (the loan shark). Mashonisas in South Africa use identical (and outlawed) collection practices such as confiscating borrowers’ ATM cards (though here the going interest rate is 50 per cent monthly), whereas formally ‘registered’ lenders (until 2016 when the Constitutional Court ruled against some of the worst practices) were using garnishee or debt recovery orders that enabled automated debt repayments (James, Citation2014, Citation2018).Footnote2 Some employers – attempting to circumvent the ease with which creditors could get their hands on the money – were resorting to paying salaries directly in cash, or by using pre-paid money cards delinked from bank accounts. Nonetheless, the negative consequences of debt and of this feeling of entrapment ranged from people resigning from their jobs to escape creditors, through cashing in their pensions, to tragic measures such as suicide.

What makes matters particularly complex and difficult to regulate is that it is far from easy to distinguish lenders from borrowers. Let me turn to a fieldwork anecdote to illustrate. The Kekana family lives in Soweto, but both parents – just like the children of Mmagojane – originally hailed from rural backgrounds. Both, as beneficiaries of the new order, have quasi-government employment; they work for a state-owned enterprise or ‘parastatal’. The mother, a frugal person, dislikes all forms of credit, but she found herself obliged to get ‘in hock’ so that their daughter could attend university after finishing high school. Financial pressures meant that the university (here turned creditor) was obliged to wait until the mother got her annual bonus before the fees could be paid. Had she secured the agreement of her husband, who thought their daughter should have gone out to work instead, it is possible that Mrs Kekana might not have been forced to shoulder this burden alone. Mr Kekana, meanwhile, was making an additional income – ‘money from nothing’ (James, Citation2015) – as a mashonisa, using his salary as a basis for his illegal moneylending business, which involved waiting outside factory gates at month end to ask borrowers for their ATM cards so as to recoup his loans plus interest from their accounts. As a state employee reinvesting in private business, he was effectively expanding his income along lines similar to those Anders (Citation2009) described. As with Anders’ example, it may well have been the case that, as a middle classer, he was obliged to send money to rural kin in the village. Although, then, his illicit moneylending activities might make him appear as a predator on others rather than a victim of inordinate requests from kinsmen, his offering of support to them would seem to cast his activities in a more positive light. What the story shows, overall, is that creditors cannot be easily distinguished from debtors since households and families may include both in complex intersection.

In sum, the salary here has become a multiple resource. It is not only a resource of which out-of-work relatives may request a share, but also, once paid from state coffers or by public companies into employees’ bank accounts, a form of collateral that underpins the offering of credit. Although not all borrowers honour their commitments, a considerable proportion of repaid debt – plus interest – ends up in the pockets of lenders. Incomes and resources are, in a number of ways, thus redistributed to those not directly receiving them. This is one way of making a living in settings perhaps misleadingly characterized as financialized or ‘neoliberal’. Through accessing state resources, money can be made ‘from nothing’: the term ‘distributional’ (Seekings & Nattrass, Citation2005, p. 314) or ‘redistributive’ should then be added to ‘neoliberal’ to create a hybrid/hyphenated adjective (Hull & James, Citation2012).

Democratic transition: Supply and demand

In telling the story of indebtedness in the global south,Footnote3 we need to examine not only the liberalization and financialization of southern economies but also the role played in them by democratic transition. In Chile, Han (Citation2012) demonstrates a relationship between that country’s earlier repressive regime and the extreme pendulum-swing of its subsequent liberalization as well as the sense that those formerly suppressed must be recompensed. The new government’s readiness to envisage the extension of credit owes something to the sense of debt, borne by the state, to those who had earlier been brutalized by it. Similarly enabling the political and economic incorporation of new swathes of people was the mass extension of credit in Brazil under Lula. This was one means – although much decried by some as unsustainable – through which the NMC or ‘new middle class’ was created and a large number of voters saw their aspirations realized (de Oliveira, Citation2012; Neri, Citation2012; de Souza, Citation2010). In South Africa something similar happened, but on a scale and to a degree that seem to mark it off as a special case from these other settings. Among them, as shown by figures from Cambridge Econometrics, the country stood out, at least during the 1990s and early 2000s, as having extremely high rates of financialization (compared for example with Mexico or Brazil) (Terry Barker, personal communication). During this period it also had very low rates of credit regulation (Makhulu, Citation2017; Schraten, Citation2018), though the years since 2010 have seen a decline in formal debt offered to the poor (Breckenridge, Citation2019).Footnote4

Newly engendered by democratic processes, immense profits were generated during the 1990s and early 2000s by the ‘financial inclusion’ of those previously marginalized. Accounts of these will likely evoke revulsion. The harm caused by financialization in general and specifically in these southern settings has been extensively documented. Epstein (Citation2005, p. 5) writes that its effects ‘have been highly detrimental to significant numbers of people around the globe’. Although my concern in the current paper is more with the everyday conundrums and ambiguities that debt has generated in the lives of borrowers and less with these broader processes, a brief account is necessary of how they unfolded.

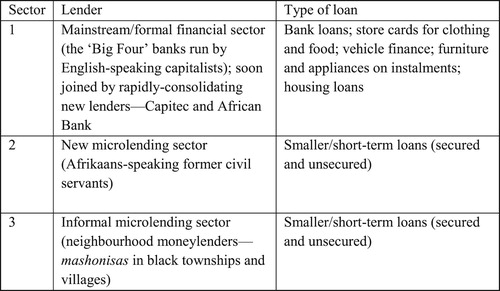

Following South Africa’s first democratic elections in 1994, when a concerted attempt to abolish the various aspects of apartheid coincided with a massive rise in expectations, numerous lenders rushed to capitalize on the many financial dealings and activities of wage earners (Krige, Citation2011; Makhulu, Citation2017; Schraten, Citation2018). But mapped onto this, and giving it a particular slant, were the ethnic and racial divisions of the country’s past and the pendulum-swing of its new inclusive dispensation. The burgeoning supply of credit that met this new demand showed marked divisions along linguistic-racial lines. Members of a rising black middle class replaced the (mostly white) incumbents of the previous civil service. It was, at least initially, these newly jobless, mostly Afrikaans-speaking, public servants that used their redundancy packages to start new microlending businesses, extending credit to those replacing them as civil servants. Other microlenders soon joined them. Some were ‘formal’ and technically legal. Others – who had long been extending loans in black neighbourhoods but now expanded their operations exponentially, to workplaces and elsewhere – were informal. Classified as ‘loan sharks’, they were known locally as mashonisas. Big banks and mainstream retailers, many of them previously reluctant (under the ‘credit apartheid’ I mentioned earlier) to offer loans to black people, soon joined in. Besides the new microlenders’ use of borrowers’ salaries as a form of collateral as described above, there were ‘unsecured lenders’ who charged even higher interest rates. This lending free-for-all had been enabled when, during the period of rapid liberalization in the 1990s, the state repealed the terms of the Usury Act which had formerly capped the interest rate (see James, Citation2014, Citation2015, pp. 65–68) ().

The past decade has seen lending continue apace but assume new forms. While formal lending to the poorer has declined in relative terms (Breckenridge, Citation2019), ingenious ways have been found of using welfare payments as loan collateral (Torkelson, Citation2020). Those with salaries remain a key target, as a 2019 report pointed out:

Unsecured lending has become pervasive among credit-active consumers in South Africa. What was once the purvey of specialist niche microlenders and illegal mashonisas has now become mainstream lending in South Africa. The large banks entered the fold and the new model allowed once-small bank Capitec to become mainstream. (Differential Capital, Citation2019, p. 7)

This plentiful supply of credit was responding to a huge demand. Everywhere in the global south (Servet & Saiag, Citation2013), but particularly in the South African case, so many would-be borrowers entered the market that offering loans to them was a sure-fire way to make a profit. An anecdotal account from someone who observed this process in the early 1990s describes the situation in vivid terms:

A large number of unscrupulous lenders piled into the market. Later, an outfit called ABIL [African Bank Investments Limited] bought out these and other small microlenders. There was a case of someone who borrowed R20,000 from his father and started extending loans at a bus depot. He lost the first R20,000, then told his father he had figured out how to do it properly and borrowed a further advance. Within a short time he had made enough money to buy a house in Johannesburg’s upmarket suburb of Sandton, for cash. (James, Citation2015, p. 66)

Escaping enslavement?

The picture which emerges, then, is an almost overdetermined one. Broader forces of financialized neoliberal capitalism, local aspirations to democratic inclusion, and expectations of redistribution rising from growing unemployment among family members, all combine to create a situation in which ‘middle classers’ find themselves unable to engage in the ‘good side’ of debt/credit (Peebles, Citation2010, p. 226) – projects of upward mobility, pursuing marriage transactions, and supporting less fortunate kin – without incurring, mostly disproportionately, the bad side – unsustainable obligations of the commodified, interest-bearing kind. Pandering to this, lenders of all types are ready to extend loans and are able to recoup these, apparently with little trouble. But are there ways of escaping from these forms of entrapment and enslavement?

Comparative evidence from southern settings suggests that, instead of wiping the slate clean, more or different kinds of debt may provide a way out. It is more common to read in the anthropological literature about people who, like the Murngin Aborigines of Australia, ‘want to owe … $5’ (Peterson, Citation1993) or, like the Amazonians described by Evan Killick (Citation2011), seek to become debt-peons of their timber-extracting partners, than to hear of people extricating themselves from such relations by cultivating an ethic of ‘detachment’ (Cross, Citation2011). The Luo in Kenya, as Shipton (Citation2007) shows, are profoundly entangled in debts, even defined by them. The reason they are often slow to honour their development loans is not because the idea of repayment is foreign to them, but because there are more important debts – to kin, and other acquaintances – that must come first. In Tamil Nadu, India, Isabelle Guérin (Citation2014) shows how women use microcredit to ‘accumulate debt ties and social relations’, and thus to ‘negotiate a better position within local spaces of sociability and wealth distribution, be these family spaces or local networks of clientelism’. In South Africa, workers have long bought furniture on instalments, made ‘lay-byes’ (put deposits on an item with retailers with the stipulation of paying the rest of the price within a set time or forfeit the deposit), or made arrangements with their employers to force them into regular savings. Debts incurred in the formal space are used in a canny manner to escape other, more social, obligations. People, argues Guérin (Citation2014), ‘negotiate and challenge’ their situations by choosing to repay some debts rather than others and juggling various creditors’ claims against each other.

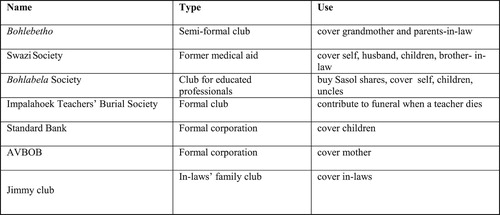

In the South African case, funeral savings clubs or ROSCAs play a similar role. These institutions, much-researched by anthropologists and ethnographers of an earlier era and now becoming even more widespread, enable the negotiation of debt/credit relationships. Lerato Mohale, for example, has a secure salaried position as a teacher, but has recently been widowed. She occupies the nodal point in a network of unemployed relatives, both her own and her late husband’s. She has taken out a range of different types of funeral cover, of which some are formal policies and others are savings club memberships: each is designated as ‘covering’ a different relative or group of relatives. Her case tersely summarizes the financial drains involved when, in a setting of rapidly increasing inequality, there is multiple reliance on a single and reliable source of income. It also illustrates that putting aside money regularly in order to honour one’s obligations to particular kinsmen is a means to stave off further demands from each intended recipient beyond what these instalments stipulate ().

If we use these positive-sounding suggestions – that conflicting obligations can provide a means to ‘negotiate’ relationships – we can revisit the story of bridewealth and explore how it relates to both apparently more commodified forms of debt in South Africa, as discussed earlier, and also to so-called blood relationships. Several anthropologists show – much as was observed by Junod for an earlier period – that few nuptials are ever finalized, and marriage payments are honoured more in the breach than in the observance. In poorer communities, men who were formerly wage-earners and are now unemployed and/or welfare dependant, continue to value ceremonial expenditures and investments in the long-term future but cannot afford them: something that has made for a deep-seated sense of failure and of psychic, social and cognitive dissonance. Although ‘completed bridewealth payments are a distant dream for most young men … they nonetheless are trapped in endless accountings of outstanding debts and fines to their partners’ relatives’ (White, Citation2011, p. 7). For ‘middle classers’ like Mmagojane’s children, the increasing financial independence of women, in this society where gender equality is assured by the constitution and in employment practices, has had similar effects. Using Anne Stoler’s (Citation2003) idea of ‘tense and tender ties’, I have written elsewhere about how women in this demographic are set apart, in terms of income, from their less fortunate relatives even as they continue to have to support and remain intimate with them; and of how they separate from male partners who expect them to conform to conservative female roles even as they continue to hold positive views about marital exchanges (and payments) more generally (James, Citation2016). I have come across both men and women who prefer to remain single, viewing the expenses of marriage as prohibitive. But people who have climbed rapidly up the social ladder, and are expected to provide their children with higher education, may also be expected – on loan or as a non-repayable ‘entrustment’ (Shipton, Citation2007) – to provide some or most of the money that makes it possible to send a nephew or niece to university. In other words, resolving to withdraw from the complex obligations of marriage exchange that tie one to potential in-laws usually means fulfilling alternative demands from one’s ‘blood’ relatives instead.

But might such demands not be kept at bay? Mmagojane’s children might, of course, have attended to the advice offered by Phumelelo Ndumo (Citation2011). In the popular self-help book From debt to riches that draws on many actual cases, Ndumo tries to enable people to avoid the conundrums they face because of family members’ requests by advocating frugality and ‘belt tightening’. She enjoins people not to be too ‘kind and well-meaning’, since this puts them at risk of being ‘taken advantage of by those they love’ (Ndumo, Citation2011). Heeding to her advice not to be a ‘cash cow’, and rather to focus on the future achievements and needs of one’s own children, such advice might enable the staving-off of relatives’ by ‘middle classers’ settling in one of the many new ‘townhouse or condominium complexes’ that are being built. Such complexes offer ‘no deposit’ arrangements akin to the 100 per cent mortgages that were available in the United Kingdom before the 2007-8 crash, allowing people who secured formal employment as a result of the democratic transition, but who lack savings, to buy apartments. The onerous regulations laid down by the body corporates who run such complexes allow residents, as Ivor Chipkin (Citation2013) points out, to ‘negotiate diverse and complex histories of family … in their own space’ – providing a safe haven that allows them to avoid the undue demands of kin. In this way, attentive to the tense situations that endless requests by family members can create, as with the Chilean poor of Clara Han’s account or the Malawian civil servants of Anders’ one, people like Mmagojane’s children are able to create the circumstances in which, as individuals, or in smaller, even single-parent households, they might progress and advance.

However, this leaves unanswered questions about middle-class ethics. Does one gain greater prestige – and even entitlement to be considered ‘middle-class’ – by being seen to attend to one’s relatives demands or by breaking free of them? Generally, few are able, or willing, to jettison obligation, or debt, altogether. Instead, it is usually a matter of deciding between one set of obligations and another. And honouring either of these often requires that one borrow money at interest. Again, market and non-market, neoliberal and redistributive, coexist in a tight embrace that seems to require conceptualization in some other way than by talking of ‘articulation’, or by thinking of financialized capitalism as holding sway.

The south as laboratory?

It sounds, then, as though debt can only be evaded by selecting between alternative kinds of owing. Such tactics are probably unlikely to be effective for long. But might the alternative be the emergence of a social movement of the indebted that unifies them and pushes for a longer-term solution? The #Rhodesmustfall and #feesmustfall student protests (Nyamnjoh, Citation2016), in which some members of the third generation have participated, show that many parents – unlike the Kekanas whom I mentioned earlier – lack either a regular income or the strategic savvy to choose between competing priorities, or both. As families pursue higher education for their children, debts to banks and short-term/high-interest microlenders are incurred, and non-repayment is common. The movement has secured some promises of relief to indebted graduates and future scholars, but the question is left unanswered of how the university sector – and middle classers in general – will ultimately be supported. Writing of this movement, Achille Mbembe returns us to the global stage. He argues that ‘any plausible critique of today’s political economy must … begin with a political critique of debt as one of the dominant structures of post-apartheid social relations’, but that

the defunding of higher education and rising tuition fees in South African universities are but manifestations of the global financialization of existence – a systemic process that is an integral part of the changes affecting the organisation of capitalism worldwide. The violence wrought on people’s lives by the ‘debt machine’ … is therefore far from a South African predicament only. (Mbembe, Citation2015)

Is it the case, then, that Africa, Asia and Latin America represent some kind of laboratory in which disturbing new schemas of financialization are trialled? John Comaroff and Jean Comaroff (Citation2012) write that these societies are the vanguard of the epoch, ‘making them at once contemporary frontiers and new centers of capitalism – which … in its latest, most energetically voracious phase, thrives in environments in which the protections of liberal democracy, of the rule of law, of the labor contract, and of the ethics of civil society are, at best, uneven’. A few examples may be used to illustrate their claim. One is that of the use, and later export, of an innovative electronic payroll system, Persal. Developed in South Africa, it entailed a function enabling the automated collection of debts, meaning that lenders suffered little risk of non-repayment (Porteous with Hazelhurst, Citation2004, p. 77).Footnote6 When, after the extent of the resulting lending frenzy became clear, the government banned this process and the sixth largest bank, Saambou, collapsed as a result of its inability to recoup its many loans (Breckenridge, Citation2018; Comaroff & Comaroff, Citation2012), similar systems were exported and used to make salary-deduction debt repayments in a number of other countries on the African continent.

Moving even further afield, there is the case of the export of the payday lending model in its starkest form, as Wonga.com, to the United Kingdom. It was founded by a South African, Errol Damelin. When criticized for its high interest rates, Damelin, like other similar payday lenders, offered the familiar defence: regulating them would simply drive people into the waiting arms of loan sharks. Belying any suggestion that its products had been forced on an unwilling populace, however, there is evidence that borrowers, needing its services, actually favoured the way they were packaged. A report, commissioned by the UK’s FCO that was researched and written by anthropologists and others, showed that payday loans seemed to offer a solution more short-term and easily controllable than any alternative. Some preferred these loans because they were easy to apply for and could be secured online rather than requiring the embarrassment of personal contact with a relative or bank manager. Other clients were ‘suspicious of, or even hostile towards credit cards’, feeling that they ‘fuelled temptation and made it too easy to get into trouble’. They opted instead ‘for short-term, high interest loans’ that (they thought) ‘made it easier to “self-police”’ (Rowe et al., Citation2014). Nonetheless, as soon as such consumers found themselves unable to pay back such loans within the ‘short-term’ as they had intended, they ended up in a debt trap with interest rates escalating uncontrollably, and with the payday lenders reaching into their bank accounts to readily recoup their money or using allegedly legal – but illicit – threats. Eventually, under increasing pressure from the media and under threat of stringent regulation by the Financial Conduct Authority – Damelin stepped down from its management in June 2014. In acknowledgment of its unethical debt collection practices, Wonga was subsequently required to pay £2.6 million in compensation to customers, and in 2018 it went into administration, suggesting that those products developed in southern ‘laboratories’ may not easily be able to survive their utilization in settings with more stringent regulation.

Conclusion

We might read much of the material presented above, along with Mbembe’s statement, as implying that debt has reached destructive levels of influence on the lives of people (especially where the ‘protections of liberal democracy … are uneven’ (Comaroff & Comaroff, Citation2012)), who are thus more marginalized and disadvantaged than ever by the encroachment of financialization. And the case of Wonga suggests that importing these practices up north and around the world augurs a similar moment of unregulated excess for borrowers everywhere. I hope to have provided some evidence that, although this may indeed be true, this alarming prospect gives us only part of the picture.

I have questioned the tendency to classify economic processes on either side of the capitalist/non-capitalist divide and assume that the financialized version of capitalism trumps everything, by drawing attention, in comparative vein, to the situation of new middle classers. In doing so, I have argued that, in newly democratized and newly liberalized southern settings, state actors are unusually responsive to the wishes and needs of the rank and file. As part of this, state employment represents a disproportionately large measure of the economic opportunities through which middle classers may earn their livelihood. Their particular version of indebtedness has come about under pressure, not only from the lenders taking advantage of their state salaries to provide an easy system of repayment, but also from less well-off family members who may see them as ‘cash cows’.

In the final section, exploring the claim that ‘Europe is evolving towards Africa’ (Comaroff & Comaroff, Citation2012), I offered only a half-hearted endorsement of it. It is true, however, that indebtedness is on the rise in both northern and southern settings. In both, we seem to be witnessing a peculiar contradiction: critics, self-help advocates and do-gooders want to restrict a credit system for the good of people whose circumstances incline them to continue borrowing and lending without restriction. But where the formal/informal, market/non-market divide is blurred, in the way that Guyer and Shipton described, lenders’ self-justificatory discourses often have some resonance for those aspiring, however precariously, to something better. Since credit apartheid of various kinds often continues to make formal lending inaccessible, borrowers on the margins, or who formerly lacked access, will insist on their right to take out loans. Faced with a fractured and divided credit landscape, they will find ways of going to lenders that they view as being ‘on their side’, negotiating and balancing diverse obligations against each other, and reverting to discourses of ‘self- control’ and ‘belt-tightening’ when things do not work out. Accounts of financialization that imply a one-way, top-down intrusion by the market into people’s intimate relations see these commitments and aspirations as imposed on unwilling victims. They ignore the deeply felt ‘tender ties’ (Stoler, Citation2003) that might make participants complicit in debt, just as they are in life.

Acknowledgments

The research for this paper was funded by Grant RES-062-23-1290 by the Economic and Social Research Council of the United Kingdom for the project ‘Investing, Engaging in Enterprise, Gambling and Getting into Debt: Popular Economies and Citizen Expectations in South Africa’, which I gratefully acknowledge. Opinions expressed are my own. For comments and suggestions, thanks to Max Bolt, George St Clair, Johnny Parry; colleagues at the University of Edinburgh, where I first presented this paper as a Munro Lecture; and colleagues at the LSE and University of Bayreuth.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Deborah James is Professor of Anthropology at LSE. Her book Money from nothing: Indebtedness and aspiration in South Africa (Stanford University Press, 2015) explores the lived experience of debt for those many millions who attempt to improve their positions (or merely sustain existing livelihoods) in emerging economies. She has also done research on advice (especially debt advice) encounters in the context of the UK government’s austerity programme.

Notes

1 Seen from creditors’ point of view, the term describes a new ‘pattern of accumulation in which profit making occurs increasingly through financial channels rather than through trade and commodity production’; seen from that of borrowers, it means that they are ‘confronted daily with new financial products’ (Krippner, Citation2005, pp. 173–174), and that those previously unschooled in matters of saving, borrowing and repaying are enjoined to become ‘financially literate’ (Krippner, Citation2005, pp. 173–174), often actively modelling their use of money along more formal lines in what has been called ‘financialisation from below’.

3 It is still relatively low in comparison with that in OECD countries (Breckenridge, Citation2019).

4 Whereas consumer credit markets were originally established in capitalist societies with moderate inequality, regulated labour markets and substantial social protection in the form of welfare states, South Africa was and is (when measured by the Gini co-efficient) the most unequal society in the world, with high levels of poverty, unemployment and insecure incomes (Schraten, Citation2018).

5 For the High Court judgement see http://www.sun.ac.za/english/Downloadable%20Documents/News%20Attachments/Judgment%20Universityof%20Stellenbosch%20Law%20Clinic%20080715%20(2).pdf.

For the later judgment by the Constitutional Court, see http://www.saflii.org/za/cases/ZACC/2016/32.html.

6 As outlined by Roth, wages paid directly into employees’ bank accounts enable employees – and lenders – to ‘use their expected wages as a collateral substitute’ (Roth, Citation2004, p. 78).

References

- Anders, G. (2009). In the shadow of good governance: An ethnography of civil service reform in Africa. Brill.

- Barchiesi, F. (2011). Precarious liberation: Workers, the state, and contested social citizenship in postapartheid South Africa. SUNY Press.

- Breckenridge, K. (2018). The global ambitions of the biometric anti-bank: Net1, lockin and the technologies of African financialisation. International Review of Applied Economics, 33(1), 93–118.

- Breckenridge, K. (2019). Networks of mistrust: Ratings, collateral and debt in the emergence of African cyberfinance. Unpublished seminar paper. WISER, University of the Witwatersrand.

- Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction. Routledge.

- Chipkin, I. (2013). Capitalism, city, apartheid in the 21st century. Social Dynamics, 39(2), 228–247.

- Comaroff, J. & Comaroff, J. L. (2012). Theory from the South: Or, how Euro-America is evolving toward Africa. Anthropological Forum, 22(2), 113–131.

- Cross, J. (2011). Detachment as a corporate ethic. Focaal – Journal of Global and Historical Anthropology, 60, 34–46.

- de Oliveira, L. (2012). La nueva clase media brasileña. Pensamiento iberoamericano, 10, 105–132.

- Differential Capital. (2019). Unsecured lending has consumers Sliding towards financial ruin - How do we reverse course? Retrieved November 4, 2020, from https://www.differential.co.za/media

- Epstein, G. A. (2005). Introduction: Financialization and the world economy. In G. A. Epstein (Ed.), Fincialization and the world economy. Edward Elgar.

- Guérin, I. (2014). Juggling with debt, social ties, and values: The everyday use of microcredit in rural South India. Current Anthropology, 55(Supplement 9), S40–S50.

- Guyer, J. (2004). Marginal gains: Monetary transactions in Atlantic Africa. University of Chicago Press.

- Han, C. (2012). Life in debt: Times of care and violence in neoliberal Chile. University of California Press.

- Hull, E. & James, D. (2012). Introduction: Local economies and citizen expectations in South Africa. Africa, 82(1), 1–19.

- James, D. (2014). ‘Deeper into a hole?’ Borrowing and lending in South Africa. Current Anthropology, 55(S9), S17–S29.

- James, D. (2015). Money from nothing: Indebtedness and aspiration in South Africa. Stanford University Press.

- James, D. (2016). Not marrying in South Africa: Consumption, aspiration and the new middle class. Anthropology Southern Africa, 40(1), 1–14.

- James, D. (2018). Mediating indebtedness in South Africa. Ethnos, 83(5), 814–831.

- Killick, E. (2011). The debts that bind us: A comparison of Amazonian debt-peonage and US mortgage practices. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 53(2), 344–370.

- Krige, D. (2011). Power, identity and agency at work in the popular economies of Soweto and Black Johannesburg. Unpublished DPhil dissertation. University of the Witwatersrand.

- Krippner, G. R. (2005). The financialization of the American economy. Socio-Economic Review, 3(2), 173–208.

- Kuper, A. (1982). Wives for cattle: Bridewealth and marriage in southern Africa. Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Kuper, A. (2016). Traditions of kinship, marriage and bridewealth in southern Africa. Anthropology Southern Africa, 40(1), 267–280.

- Lentz, C. (2016). African middle classes: Lessons from transnational studies and a research agenda. In H. Melber (Ed.), The rise of Africa’s middle class: Myths, realities and critical engagements (pp. 17–53). Zed Books.

- Makhulu, A.-M. (2017). The debt imperium: Relations of owing after apartheid. In W. Adebanwi (Ed.), The political economy of everyday life in Africa: Beyond the margins (pp. 216–238). James Currey.

- Mbembe, A. (2015). The debt machine and the politics of 0%. Groundup. Retrieved from http://www.groundup.org.za/article/debt-machine-and-politics-0_3506/.

- Ndumo, P. (2011). From debt to riches: Steps to financial success. Jacana.

- Neri, M. C. (2012). A nova classe média: o lado brilhante da base da pirâmide. Saraiva.

- Nyamnjoh, F. (2016). #Rhodesmustfall: Nibbling at resilient colonialism in South Africa. Langaa Research and Publishing Common Initiative Group (Langaa RPCIG).

- Parry, J. (2012). Suicide in a central Indian steel town. Contributions to Indian Sociology, 46(1&2), 145–180.

- Peebles, G. (2010). The anthropology of credit and debt. Annual Review of Anthropology, 39, 225–240.

- Peterson, N. (1993). Demand sharing: Reciprocity and the pressure for generosity among foragers. American Anthropologist, 95(4), 860–874.

- Porteous, D. with Hazelhurst, E. (2004). Banking on change: Democratizing finance in South Africa, 1994–2004 and beyond. Double Storey Books.

- Roth, J. (2004). Spoilt for choice: Financial services in an African township. PhD dissertation. University of Cambridge.

- Rowe, B., Holland, J., Hann, A. & Brown, T. (2014). Vulnerability exposed: The consumer experience of vulnerability in financial services. Report for FCA by ESRO. Retrieved from https://www.fca.org.uk/static/documents/research/vulnerability-exposed-research.pdf.

- Schraten, J. (2018). Credit and debt in an unequal society: Establishing a consumer credit market in South Africa. Berghahn.

- Seekings, J. & Nattrass, N. (2005). Class, race, and inequality in South Africa. Yale University Press.

- Servet, J.-M. & Saiag, H. (2013). Household over-indebtedness in contemporary societies: A macro-perspective. In I. Guérin, S. Morvant-Roux & M. Villarreal (Eds.), Microfinance, debt and over-indebtedness: Juggling with money (pp. 45–66). Routledge.

- Shipton, P. (2007). The nature of entrustment: Intimacy, exchange and the sacred in Africa. Yale University Press.

- Souza, J. (2010). Os Batalhadores brasileiros. Nova classe média ou nova classe trabalhadora. Belo Horizonte: Editora UFMG.

- Stoler, A. L. (2003). Tense and tender ties: The politics of comparison in (post) colonial studies. Itinerario: Special Issue, 27(3-4), 263–284.

- Torkelson, E. (2020). Collateral damages: Cash transfer and debt transfer in South Africa. World Development, 126, 104711. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0305750X19303596.

- Trapido, S. (1978). Landlord and tenant in a colonial economy: The Transvaal 1880–1910. Journal of Southern African Studies, 5(1), 26–58.

- White, H. (2011). Youth unemployment and intergenerational ties. Paper presented to workshop “Making Youth Development Policies Work,” Centre for Development Enterprise.

- Wolpe, H. (1972). Capitalism and cheap labour power in South Africa: From segregation to apartheid. Economy and Society, 1(4), 425–456.

- Zaloom, C. (2019). Indebted: How families make college work at any cost. Princeton University Press.