ABSTRACT

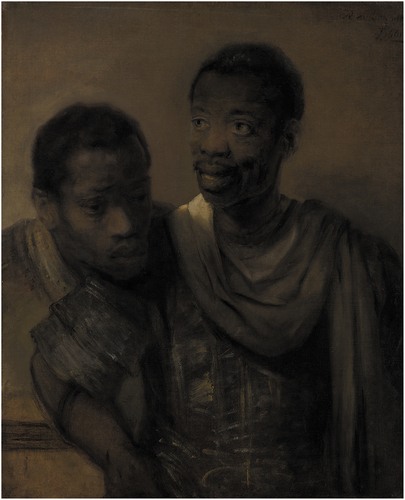

In this article I take a critical look at the ‘cultural archive’, one of the key concepts in White Innocence (2016), for which Gloria Wekker drew methodological inspiration from Edward Said, who coined the term in Culture and Imperialism (1993), and from Ann Laura Stoler’s observations on the ‘ethnography of the archive’ in Along the Archival Grain (2009). Drawing on debates in history, cultural analysis and memory studies, and using Rembrandt van Rijn’s painting ‘Two African Men’ as case study, I wish to elaborate on Wekker’s observations on what the cultural archive as a conceptual tool allows us to see about Dutch history, memory and society, and what it obscures. Despite its obvious advantages for recognizing and acknowledging structures of coloniality still present in Dutch society, I plead for a more historically grounded approach to the cultural archive that may enhance the productivity of future research on, or in, the cultural archive in order to identify further possibilities of change.

The publication of Gloria Wekker’s monograph White Innocence: Paradoxes of Colonialism and Race in 2016, and its translation into Dutch, Witte onschuld: Paradoxen van kolonialisme en ras the year after, caused a stir, both in the Netherlands and abroad.Footnote1 It received an abundant number of reviews, not only in academic journals but also in Dutch mainstream media, an exceptional achievement for an academic book.Footnote2 White Innocence was a stone in the pond that made many ripples in and beyond academia, and is still doing so, as is demonstrated by its reaching its sixth print run in 2020, the countless public debates and lectures to which Wekker has been and continues to be invited, and the prizes and honorary doctorate that she has received. Thus, White Innocence is what we may call a form of symbolic social action: a book that has made things happen.

In White Innocence Wekker probes racism and coloniality in Dutch society, effectively combining autobiographical, historical and anthropological analysis. While various reviewers have remarked on Wekker’s eclectic methodology, not always approvingly, internationally there are many books that similarly mix personal experiences with theoretical reflection and social critique, often inspired by the feminist motto ‘the personal is political’: from the early example of Carolyn Steedman’s Landscape for a Good Woman (1987), to Margo Jefferson’s Negroland (2015) and Hazel Carby’s recent Intimate Imperialism (2020). I would contend it is precisely because of this mix of personal vignettes and more theoretical arguments that White Innocence was able to have such an impact. The book has given an enormous impulse to a nationwide conversation about race and racism, in which it has become a standard point of reference. It has given a new generation of anti-racist academics and activists in the Netherlands the tools to continue that work.

Wekker’s book helped create momentum in the anti-racist engagements that had (re)emerged in various societal and academic contexts in the Netherlands in the years preceding its publication, and enabled seeing these as related: from anti-Black-Pete activism, Black Lives Matter and student protests, to debates about the coloniality of museum collections, and initiatives to rethink colonial archives.Footnote3 Thus, it was a book in the right place at the right time, which brought many of the ideas that had already been circulating in the women’s movement since the early nineteen-eighties to the surface of Dutch twenty-first century mainstream media and academia. An episode that Wekker describes in White Innocence may illustrate this. As a member of the black lesbian feminist group Sister Outsider, Wekker was one of the people to invite the poet, scholar and activist Audre Lorde to the Netherlands in 1984. Afterwards, the lesbian-feminist journal Lust & gratie (Lust & Grace) published a long interview with Lorde.Footnote4 It is striking how many of Lorde’s observations are similar and still relevant to the arguments Wekker presents in White Innocence, almost four decades later. However, there is a striking difference in the ways in which these ideas were received and disseminated today and back in 1984. Apart from the interview in what we could qualify as a counter-cultural journal, the only other medium to register Lorde’s visit at the time was the communist newspaper De waarheid (The Truth).Footnote5 This is in sharp contrast with the vast number of reviews, interviews, blogs and articles that have been published about White Innocence, which underlines the resonance of Wekker’s intervention in contemporary discourse and debate.

Labelling White Innocence a form of ‘symbolic social action’ – a book that made things happen – helps to sidestep for a moment the thorny issue of the relations between words and worlds: the phrase conveniently captures both dimensions of the symbolic and the social, of thoughts and arguments on the page and their reverberations in society in the form of debate, affect or policy reform. How can we actually know how books have an impact? As a scholar of literature, I am particularly preoccupied by this question and eager to know how books make a difference in the world or in people’s lives. Did Uncle Tom’s Cabin help speed up the abolition of slavery, as is commonly believed? Or, to stay closer to home and my own research, how did Gerard Reve’s work move the sexual emancipation of Dutch homosexuals forward? Can we identify the moments readers were affected, moved, mobilized by literary or other publications? Can we call this cause and effect, or should we rather conceive of books in a Latourian vein, as nodes in a network of many different actors in which each has its own agency, and one cannot exist without the other? Which concepts and methods can we use to make any substantial claims about the connections between cultural texts and cultural acts? Counting reviews, as I did in the previous paragraph, probably does not suffice.

These questions also pertain to Wekker’s White Innocence, as the book’s main aim is to show how Dutch colonial history, and the way it has (not) been dealt with in Dutch society, still impacts contemporary Dutch culture and society. Wekker argues that white innocence, which she defines as the congratulatory self-image of being colour blind, is ‘a dominant way the Dutch think about themselves’,Footnote6 and the result of four hundred years of Dutch colonialism, of a past denied or mythologized. However, identifying the connections between those two poles – Dutch colonial history on the one hand and current white self-conceptions on the other – is easier said than done. In what follows, I will take a closer look at Wekker’s key concept of the cultural archive to think through the relations between colonial past and racist present, and reflect on how we can build on Wekker’s trailblazing work. While the cultural archive performs necessary cultural work in the present, it is my argument that it needs to be conceptualized with greater precision to render it productive in a broader range of contexts. Wekker’s take on the cultural archive, I will argue, runs the risk of turning it into a monolithic conceptual tool with too little analytical power, which precludes an understanding of the cultural archive as layered, and of the recent and colonial past as dynamic and as containing seeds for change.

The Cultural Archive

Wekker defines the cultural archive in White Innocence as ‘the unacknowledged reservoir of knowledge and affects based on four hundred years of Dutch imperial rule’.Footnote7 It is ‘located in many things, in the way we think, do things, and look at the world, in what we find (sexually) attractive, in how our affective and rational economies are organized and intertwined’; in short, it is ‘a repository of memory in the heads and hearts of people in the metropole’.Footnote8 From these descriptions it is clear that the cultural in the cultural archive is understood by Wekker not just in its narrow artistic, literary or cultural studies sense as the texts and artefacts produced and circulated in a particular community, but also in a more anthropological sense, as the shared practices, sentiments and habits of a group, as indicated by her use of ‘we’, ‘affects’, and ‘hearts’. Before going into the consequences of this broader understanding of the cultural, I wish to zoom in on the theorists who inspired Wekker’s use of the concept of the cultural archive: Edward Said and Ann Laura Stoler.

As Wekker indicates herself, she takes her cue in the first place from Edward Said, who coined the term cultural archive in Culture and Imperialism (1993), successor to his seminal work Orientalism (1978). However, Wekker’s understanding of the cultural archive is broader than Said’s (and in fact closer to his concept of orientalism). Said brings up the term ‘cultural archive’ on three occasions in Culture and Imperialism, and each time references to literary works by Kipling, Austen or Dickens are not far away. Said conceives of these and other texts as cultural sites ‘where the intellectual and aesthetic investments in overseas dominion are made’ and which helped instil a sense of white western superiority in their readers.Footnote9 A telling Dutch example of this matter-of-course-coloniality is Woutertje Pieterse, the thirteen-year-old hero of Multatuli’s eponymous book (Multatuli 1921 [1890]). Multatuli (Eduard Douwes Dekker’s pen name) is best known for his novel Max Havelaar (1860), in which he rallies against the exploitation of the Javanese people as a consequence of Dutch colonial policy, though he was not opposed to colonialism as such. In his later work Ideën (1890), from which Woutertje Pieterse was posthumously compiled, Multatuli demonstrates the unquestioned self-evidence of coloniality in Dutch nineteenth-century thought, presenting his readers with a protagonist who in many respects is the underdog – shy, dreamy, and easily intimidated – but who, without any effort, is able to imagine himself as a future king in Africa. Although, arguably, it is no more than an escapist fantasy for Woutertje, the ease with which it is conjured up, its ready availability, is a telling sign of the protagonist’s colonial mentality.

The colonial worldviews articulated in texts such as these, as Said’s by now familiar argument goes, translated into ways of looking, ways of talking, ways of acting. Said’s ground-breaking insight was to show the extent to which European colonialism was not just a military and economic endeavour overseas, but a system supported by and engrained in an extensive tissue of cultural and scholarly texts in the metropole. When Said called for a reinterpretation of the cultural archive, he called for a recognition of the thus far unacknowledged coloniality of cultural, often canonical, European texts which helped shape colonial thinking in the imperial centre. Thus, ‘comparative literature, English studies, cultural analysis’ were the first disciplines Said mentioned, and although these disciplines have certainly heeded his call, also in the Netherlands, much work still needs to be done.Footnote10 (For instance, to my knowledge, an analysis of coloniality in Woutertje Pieterse does not yet exist.) The histories of other fields of knowledge production affiliated with colonialism and empire, such as anthropology, should also be scrutinized and reinterpreted, work that Said himself already started in Orientalism. Unlike Said, who regards the discipline of anthropology as part and parcel of the cultural archive, as a historical source to be analysed, Wekker conceives of the cultural archive as an analytical tool for anthropologists who aim to analyse the present, which is precisely what she does in White Innocence. As Wekker remarks, Said ‘does not give many clues as to how to operationalize [the cultural archive] outside the domain of culture taken as poetry and fiction’.Footnote11 While Said did considerable work on discourse analysis of other textual genres (travel journals, scholarly texts) in Orientalism, it is true that he is not really concerned with a wider range of genres or societal issues, such as the dissemination of the texts he analyses, or with actual readers. This also means that he repeatedly makes the leap from word to world, drawing conclusions about shared mentalities based on the analysis of individual works, yet all within the historical framework of imperialism.

In addition to Said, Wekker draws on the work of historical anthropologist Ann Laura Stoler, who in her book Along the Archival Grain (2009) employs what she calls an ‘ethnography in and of the colonial archive’.Footnote12 Stoler is interested in the culture of the archive, in studying ‘the words in their sites’: she is concerned with the ‘how’ as much as with the ‘what’ of knowledge production as manifested in the marginalia and the gaps in sources, to try and retrace the ‘changing parameters of common sense’.Footnote13 Stoler’s attention to the material and affective aspects of the archive does produce many new insights into the conditions of colonial conventions which produced a colonial ‘common sense’. By painstakingly following her archival sources and subjects within their different contexts, Stoler shows the vicissitudes of, and the frictions in, the colonial archive. Through her focus on the changing discourses of colonial administrators, she is able to interpret what could and could not be thought and said at different moments. While at first sight Stoler’s ‘ethnography of the archive’ may sound quite similar to Wekker’s ‘cultural archive’, they are rather different. Like Wekker, Stoler is interested in the hearts and habits of the subjects she studies, and in that sense they share an interest in what can be found beyond the page, not just as hidden meanings, but as affects and habits. However, as a historian Stoler always relies on (textual) sources, be they official documents or personal letters. More so than Wekker, she is concerned with the ways colonial common sense was a product of fractured, paradoxical, and at times conflicting discourses. Another marked difference lies in the scope of the archive that the two scholars study. Stoler’s object of analysis is the nineteenth-century Dutch colonial administration kept in the Dutch National Archive in The Hague, and as such it is a rather well delineated object. However, as Stoler recognizes, the boundaries of archive in its narrow sense at times tend to blur into the broader notion that has gained in popularity in the past twenty years: the archive as ‘a metaphoric invocation for any corpus of selective collections and the longings that the acquisitive quest for the primary, originary and untouched entail’.Footnote14

Wekker’s archive is of this second, broader kind and, unlike Stoler’s, hardly includes historical material from the colonial era. With the exception of one psycho-analytical case study from 1917, her sources are dated after 1945 and not drawn from institutional archives or fiction, but from popular media – newspapers, television, social media – and, to a lesser extent, from art; her topics range from the self-presentation of Dutch gay politician Pim Fortuyn to responses to Black Pete. In addition to these public (media) texts, Wekker analyses her personal experiences with racism. For this, she is inspired by Bourdieu’s ‘habitus’, as is Stoler, and describes this notion as ‘“history turned into nature”, structured and structuring dispositions, that can be systematically observed in social practices’.Footnote15 This results in thick descriptions of the racist attitudes and responses that Wekker has encountered in social and institutional practices: on public transport, at lectures, in policies or in the workplace, comparable to the pioneering work of Philomena Essed in Everyday Racism (to which Wekker also refers).Footnote16

Although the similarity in terminology may suggest that their approaches are similar, Wekker is methodologically far more daring than Said and Stoler. The main difference is that both Said and Stoler confine their analyses to (textual) sources from the colonial past, more specifically the nineteenth century, and draw comparisons between the archive they study and other societal norms and habits only on a contemporary plane, in which the archive functions as a driving or explanatory force for the colonial mentalities of the period under scrutiny. Wekker does not study the 400-year old cultural archive in the making, nor does she analyse the relations between historical (colonial) archive and its contemporary context. Rather, she takes the (historical) colonial cultural archive more or less as a given and looks at the end result: the twenty-first-century white Dutch identity it has produced. She does not conceive of the cultural archive as a uniform entity though, or so she states:

I am not implying that the cultural archive or its racialized common sense has remained the same in content over four hundred years, nor that it has been uncontested, but those historical questions, important as they are, are not, cannot be my main concern. Standing at the end of a line, in the twenty-first century, I read imperial continuities back into a variety of current popular cultural and organizational phenomena.Footnote17

Wekker’s position is politically defensible, as it is her main purpose to address the patterns of coloniality and racial inequality in contemporary Dutch society and to criticize a deceptive self-image of white liberal Dutch identity, as a twenty-first-century J’accuse. However, this stance may not always be conducive to gaining greater insight into the precise workings of the cultural archive, certainly not just for scholars with more profound historical interests than Wekker, but ultimately also not for those with political aims. Wekker’s operationalization of the cultural archive appeals to indignation and shame – which probably explains its success – but, as I will argue, by disregarding historical questions, and thus the dynamics of culture over time, Wekker ultimately precludes a better understanding of how past and present interact, interactions that could also help fuel change.

The problem is that, notwithstanding Wekker’s earlier references to its dynamic nature, the cultural archive, more often than not, appears as a monolith in White Innocence, a collective unconscious, a site of repressed memories specific to the Dutch, or, alternatively, a site of feigned or wilful (smug) ignorance about Dutch colonial history. Wekker speaks of a ‘submerged knowledge’ and a ‘repressed cultural archive’,Footnote18 and, elsewhere, of an ‘unexamined Dutch cultural archive’.Footnote19 Each of these terms comes with different connotations, which raise different issues: if the cultural archive is submerged, or even repressed, we may wonder at what level ‘we’ can address or gain access to it, if at all. If we can only recognize the cultural archive in its symptomatic manifestations, as the psychoanalytic terminology of repressed memory would suggest (at one point Wekker speaks of ‘releasing pent-up feelings brewing in the cultural archive’Footnote20), we may wonder whether we can ever unlearn anything (including our innocence) by learning about it, which is rather discouraging. On the other hand, her conception of the cultural archive as an unexamined reservoir prompts Wekker to address instances of white innocence in Dutch society, so that her book, like Said’s Culture and Imperialism, functions as a necessary wake-up call, but about the present rather than the past. Yet, if the cultural archive has hitherto been left unexamined, it may be fruitful to address not only the continuities in it, as Wekker does, but also the vicissitudes, as Stoler suggests. In other words, if we do not analyse how colonial mentalities were formed over time, we cannot understand how they live on, nor how they could be changed.

Wekker’s focus on the continued racialized content of the Dutch cultural archive runs the risk of turning it into a totalizing discourse, despite her remark about the archive as contested: ‘I read all of these contemporary domains for their colonial content, for their racialized common sense’.Footnote21 While I recognize the importance of addressing and deconstructing the presence of coloniality in Dutch society – from Black Pete to a dubious holding named after a VOC-shipFootnote22 –, by assuming that coloniality is always already there, and that racialized common sense is a given rather than a dynamic equilibrium, as Stoler would have it, Wekker forecloses a further analysis of the cultural archive, whether present or past. If, as Wekker claims, Dutch white innocence is the outcome of four hundred years of colonial rule – a past denied or mythologized – to what extent has half a century of postcolonial reality, or seventy years in the case of Indonesia, had an impact? None whatsoever? Not enough, so much is clear, but because Wekker does not address this question at all, it is impossible to gauge any change.

In order to track and trace any counter-currents, I would like to propose a more nuanced and historically grounded approach to the cultural archive, past and present, with the help of two other theorists. The first is the Welsh writer and academic Raymond Williams, who inspired both Said and Stoler, and who grappled with the problem of how to account for cultural change. Through his notion of ‘structure of feeling’ Williams argued that the dominant way of thinking in a particular society can never be total: ‘structure of feeling is not uniform throughout the society; it is primarily evident in the dominant productive group’.Footnote23 Thus it becomes possible to think about change: Williams allows us to see culture as an arena of contesting and contested discourses, habits and behaviours, in which new patterns can emerge. Or rather, because new patterns do emerge, we have to assume the dynamism of culture, a dynamism capable of producing new formations of thought that ‘appear in the gap between the official discourse of policy and regulations, the popular response to official discourse and its appropriation in literary and other cultural texts’.Footnote24 Approaching the cultural archive in this way, as Said first did in Orientalism, and as Stoler did by analysing the marginalia and inner contradictions of colonial administration, or as Williams himself did beautifully in his novel about his Welsh youth, Border Country (1960),Footnote25 does not amount to a denial of the dominance of a particular discourse or pattern of behaviour, but it makes counter-currents visible. It is part of what Williams called ‘unlearning the inherent dominative mode’, a phrase quoted approvingly by Said in Orientalism.Footnote26 This is important, I would like to argue, because the manner in which we actualize the cultural archive affects the present.

The second pathway I want to suggest to arrive at a more nuanced understanding of the cultural archive, is via cultural memory studies, which provides us with other, helpful tools for discussing the remembered and forgotten remnants of culture. At first sight cultural memory as defined by Aleida Assmann is strikingly similar to Bourdieu’s definition of habitus: both call it ‘the past in the present’, but where Bourdieu refers to the way certain habits are socially reproduced, Assmann refers to the way in which cultural artefacts are retained and revived in the present.Footnote27 She makes a distinction between what is actively remembered and preserved in the present (for example, the canon or the museum’s exhibition) and what is stored passively: the unmediated testimonies, the ‘storeroom’ that preserves the past in the past, or what Assmann calls the archive. Traffic is possible between the past as it is stored in the past on the one hand, and the past as it is brought up to date in the present on the other, so that the relation between ‘storeroom’ and ‘museum’ is dynamic and the retrieval of elements from the ‘storeroom’ can serve divergent ideological goals. For example, the historical impulse of the second feminist wave to recover forgotten women helped to return these women to the collective memory and thus contributed to a more gender-equal future. An ideologically opposite example would be the current Italian political movement CasaPound’s decision to name themselves after the American poet and Mussolini supporter Ezra Pound, and to bring his fascist ideas to bear on the twenty-first century. There is much in the storeroom of the cultural archive that ‘we’ do not know about, we as individuals, and we as collectives. I only read Woutertje Pieterse this year, and have only just learned about the Surinamese union leader Louis Doedel to give another example.Footnote28 Collectively, there are unknowns that can become known thanks to historical research, such as Sarah Adams’ discovery of forgotten eighteenth-century abolitionist plays.Footnote29 I use the plural ‘we’ here, but it is important to realize, as historian Alex van Stipriaan emphasizes, that there are different groups, different institutions, and different speeds, which complicates the picture of one white Dutch unified collective memory.Footnote30

Cultural memory constitutes identities, national as well as other collective identities. Because cultural memory is dynamic, identities are also subject to change. As the example of CasaPound illustrates, cultural icons from art, literature and popular culture are powerful sites of cultural memory, sites where memory is selected, converged and remediated, and where collective identities are shaped.Footnote31 Institutions such as museums, archives and educational institutions are crucially important to create frameworks of memory – what Paul Bijl terms memorability – which can help cement new forms of cultural memory.Footnote32 Although this is a continuous battle, one that is not without obstacles and backlashes, a rather successful example of such a new memorable framework may be the ‘window’ devoted to Aletta Jacobs in the Dutch national historical canon.Footnote33 Wekker, too, moves a number of ‘objects’ in the cultural archive from their storeroom into visibility by presenting them as case studies in her book. Although she thus allows her readers to remember these in a more active manner, she leaves the storeroom of the historical, colonial cultural archive untouched.

Layers in the Cultural Archive: Rembrandt’s ‘Two African Men’

Stoler warns students and scholars of the colonial past not to produce what she calls ‘charmed accounts’ of history that pit good against evil too easily, and ‘coat complex commitments in generic ideologies and “shared” imaginaries as if people had to do little work with them’.Footnote34 I take this as an appeal not to regard the cultural archive – contemporary or historical, or the connections between those – as a given, but to treat it as a collection of texts, practices, habits and histories that require much work. What we bring into the present from the past, and how exactly we do that, will directly affect the way we think about the present, and about ourselves, as Ilse Raaijmakers has demonstrated beautifully for the ways in which the remembrance of the Second World War has changed the self-image of the Dutch.Footnote35

To illustrate the need to work on the historical cultural archive, I will discuss one example in more detail: Rembrandt’s famous painting of two black men (1656). As an iconic piece on permanent display at the Mauritshuis (The Hague), it is a prominent component of the Dutch cultural archive. It is also a part of the transnational black archive, as is attested to by its appearance on the cover of Bindman and colleagues' standard work on representations of black people.Footnote36 Rembrandt’s painting is exceptional in the sense that it is different from many other contemporary representations of black people in European art, or so it has been argued by Simon Gikandi: it places black people in the centre of the image, not in the margins, and depicts the two men in a non-stereotypical fashion by giving them distinct, individual features.Footnote37 This explains the painting’s appeal to a modern, antiracist viewer like Gikandi, who in Wekker’s words is standing ‘at the end of the line’.Footnote38

The Rembrandt painting itself can be considered as an archive of sorts with many layers: it carries the traces of its own dynamic past, not the least through the history of its naming. Paintings often only acquire their title when they change owners, which is when they are mentioned in archival records and briefly become ‘visible’ in history. In the case of the Rembrandt painting there is a first reference to ‘Twee mooren in een stuck van Rembrandt’ (Two Moors in a piece by Rembrandt) in an inventory of Rembrandt’s belongings that dates back to 1656.Footnote39 It resurfaces well over a century later, when in 1784 it is sold to a British buyer, one Lord Joseph Berwick, at an auction in Paris. On this occasion, it is described as ‘Un sujet de deux figures vue[s] à mi-cor[ps]: il représente des têtes de nègres […]’ (a subject of two figures seen half-length: it represents blacks’ heads).Footnote40 It then remains in England, where it circulates in various private collections until 1902, when it is acquired by the Dutch Rembrandt collector Abraham Bredius. The following year it receives a Dutch title, ‘Twee negers’ (‘Two blacks’), when Bredius loans it to the Mauritshuis, at which moment it enters the (public) Dutch cultural archive.Footnote41 In 2004, the Dutch title is considered too offensive by the museum and changed back to ‘Twee Moren’, corresponding to the original mention in the inventory.Footnote42 In 2019, the title is changed once more, this time to ‘Twee Afrikaanse mannen’ (Two African men).Footnote43 These traces are both material – present in the sources, in accompanying labels and catalogues – and symbolic: they are, as changing signs, tokens of changing historical contexts, interests, and meanings of the painting, and of changing attitudes, which in turn require interpretation. Thus, we can undertake a historical ethnography of the painting.Footnote44

As I explained in a 2019 article, it is thanks to the (archival) work of Dutch historians such as Dienke Hondius and Mark Ponte that we now know there was a small population of black men and women living in Amsterdam from the early 1600s onwards – Ponte was able to identify around two hundred people.Footnote45 Some were domestic slaves or servants to Portuguese Jews – their status is often unclear because slavery was prohibited on Dutch soil – but others were free: often they were Afro-Atlantic sailors, mostly from Angola or the colonies in Brasil. In 1635, the archival records show, seven free black men and women (and their children) were living independently in what is now the Jodenbreestraat in Amsterdam, the street on which Rembrandt lived from 1639 onwards. The neighbourhood continued to attract black inhabitants in the following decades. When Rembrandt painted the two black men about twenty years later, they could very well have been second-generation free blacks in Amsterdam.Footnote46

To hear and read about this group of free black people in seventeenth-century Amsterdam was a real eye-opener. It changed my view of the Dutch past, my rather hazy sense of the Low Countries as a white country. The Rembrandt painting offers a wonderful opportunity to become aware of the presence of black people in early modern Amsterdam, even if they were few: it makes them literally visible. It allows viewers to reinterpret the Dutch cultural archive in which black presence has often gone unacknowledged and hopefully contributes to the acknowledgement and acceptance of the diversity of current Dutch society. The painting also offers an excellent opportunity to tell a complex history of Dutch and Portuguese colonialism, of the slave trade to Brasil and the Caribbean and of black migration to Amsterdam. As modern viewers, we can only recognize the two men as likely inhabitants of Amsterdam because of the work done by historians in the cultural archive. However, without access to this contextual information, visitors of the Mauritshuis will simply be presented with a painting of ‘Two African Men’, as today’s actualization of the painting stresses the men’s (or their parents’) descent rather than their presence or destination. I am aware that in the epithet ‘African’, whether used independently or as part of a hyphenated identity (as in African American), multiple meanings of descent, origin or orientation can resonate.Footnote47 Nevertheless, I find the painting’s new title a missed opportunity, because I suspect many visitors will assume the men came from Africa, while it is equally likely that they were born in Amsterdam, or had arrived there as sailors from Brasil.Footnote48 Therefore I have suggested to rename the Rembrandt to ‘Two Amsterdammers’ (‘Twee Amsterdammers’),Footnote49 or, if that is perceived as a bridge too far, as a too presentist jump from its earliest title ‘Twee Mooren’, to rename it ‘Two black men’, or ‘Two Black men’ (‘Twee zwarte/Zwarte mannen’). The latter, as a modern-day translation of the original title, also would be in line with the predominant art historical reading of this painting as a so-called ‘tronie’, a facial study focused primarily on the effects of paint colour, rather than the portrait of an individual.Footnote50

Conclusion

Wekker’s important work has made us more aware of the unacknowledged coloniality in Dutch cultural texts, but if we want our culture and society to change, we must do more than simply denounce the present-day continuities of the imperial past. After White Innocence’s wake-up call, we need to assume our responsibility as educators, researchers and curators at cultural institutions and examine how the cultural archive has come about in order to carefully consider what part of our past we render in the present and in which manner. What I hope my discussion of Wekker’s book and the Rembrandt case makes clear is that, in striving for a less racist, more just society, it is important to explore the cultural archive in its historical dimensions, for we cannot assume we already know the cultural archive and fathom its all-encompassing coloniality. When I imagine the groups of tourists and schoolchildren who will be visiting the Mauritshuis in the future, I hope they will see the two black men as part of historical Amsterdam. Historical investigations into the cultural archive, as my reading of the reception of Rembrandt’s painting demonstrates, enables us to build on Wekker’s dismissal of the cultural archive as a repressed collective memory or an unexamined repository and help us to articulate much-needed counter-narratives and develop new forms of Dutch self-awareness that challenge the now dominant sense of white innocence.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Agnes Andeweg

Agnes Andeweg is assistant professor in modern literature and cluster chair (Literature, Linguistics, Philosophy, Art History) at University College Utrecht. She specializes in modern Dutch literature, gothic fiction (1800-present), and cultural history and memory, with a focus on gender, sexuality and nationality. She has published in Early American Literature, the Journal of Dutch Literature, Cultural History, Nederlandse Letterkunde, Tijdschrift voor Genderstudies, Sexuality & Culture. In 2022 she chaired the jury of the P.C. Hooft prize for narrative prose. At University College Utrecht, she initiated the first One Book One Campus project in the Netherlands in 2018.

Notes

1. I would like to thank Geertje Mak, Mineke Bosch and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on previous versions of this article. Any remaining shortcomings are mine.

2. There are over 500 mentions of Gloria Wekker in the news database Nexis Uni since 1 January 2016, of which roughly 450 are in Dutch; there are over 400 citations (including reviews) on Google Scholar. Consulted 19 May 2021.

3. Anti Black Pete protests re-emerged around 2011; the Maagdenhuis protests in 2015 at the University of Amsterdam resulted in the Diversity report chaired by Wekker; the first Black Lives Matter protests in the Netherlands took place in 2016; Tropenmuseum (Amsterdam) opened its new permanent display “The present of the slavery past” in 2017. For an overview of developments in archival science see Jeurgens en Karabinos, “Paradoxes of Curating”.

4. Meijer and Van Dijck, “Zwijgen zal ons niet beschermen”.

5. “Zwarte schrijfster”.

6. Wekker, White Innocence, 2.

7. Ibid.

8. Wekker, White Innocence, 19.

9. Said, Culture and Imperialism, xxi.

10. Ibid., 50.

11. See note 8 above, 19.

12. Stoler, Along the Archival Grain, 32.

13. Ibid., 36, 38.

14. Ibid., 45.

15. Wekker, White Innocence, 20.

16. Essed, Alledaags racisme; Essed, Understanding Everyday Racism.

17. See note 15 above, 20.

18. Ibid., 32, 33.

19. Ibid., 137.

20. Ibid., 11.

21. Ibid., 19.

22. “Sywert van Liendens sluisde 9 miljoen euro naar persoonlijke holding”.

23. Williams, The Long Revolution, 80.

24. “Structures of Feeling”.

25. Williams, Border Country. The novel was translated into Dutch by Gerbrand Bakker (Grensland, 2014).

26. Said, Orientalism, 28.

27. Assmann, “Canon and Archive”.

28. Akkerman, “Het opbergen van Doedel”. After organizing protests Louis Doedel was put away in a psychiatric hospital against his will. He was kept there for forty-three years.

29. Adams, Repertoires of Slavery.

30. Van Stipriaan, “Dutch Dealings”.

31. Rigney, “Portable Monuments”; Rigney, “Plenitude, Scarcity”.

32. Bijl, “Colonial Memory”.

33. The Canon of the Netherlands, a website featuring the fifty most important topics in Dutch history, was first compiled in 2006 and renewed in 2020. It primarily serves educational purposes. See: https://www.canonvannederland.nl/.

34. Stoler, Along the Archival Grain, 252.

35. Raaijmakers, De stilte en de storm.

36. Bindman, The Image of the Black.

37. Gikandi, Slavery and the Culture of Taste.

38. See note 15 above, 20.

39. Kolfin, “Rembrandt’s Africans”. On the back of the work itself there is another date, 1661, which may have been added only when it was sold, which was not uncommon practice.

40. “Rembrandt, ‘Twee moren’”.

41. Ibid.

42. “Mauritshuis paste ‘gevoelige’ namen al aan”.

43. “Twee Afrikaanse mannen”.

44. I have done so in more detail elsewhere. See Andeweg, “Allegory as Historical Method”.

45. Hondius, “Black Africans”; Ponte, “Al de swarten”; Ponte, “1656: Twee mooren”.

46. Ponte notes that second-generation black people are most often invisible in the archives because only their birthplace is registered and colour is often not mentioned. Ponte, “Al de swarten”, 44.

47. See Martin, “From Negro to Black to African American”. For a more recent discussion in the context of Black Lives Matter, see Nick, “Black Rising”. A recent analysis suggests an increasing preference for “Black” rather than “African American”, see Hathaway, “They Made Us”.

48. In his descriptions of the black presence in seventeenth-century Amsterdam, Ponte uses the terms African, of African descent, Afro-Brasilian, Afro-Caribbean, Afro-Atlantic, Afro-Amsterdammers interchangeably. Ponte identified most people based on birthplace, though sometimes colour was explicitly mentioned. See Ponte, “Al de swarten”.

49. Andeweg, “Noem deze Rembrandt”.

50. Kolfin, “Rembrandt’s Africans,” 298–299.

Bibliography

- Adams, Sarah. Repertoires of Slavery: Dutch Theatre between Abolitionism and Colonial Subjection, 1770-1810. PhD Diss. Universiteit Gent, 2020. Accessed May 19, 2021. http://hdl.handle.net/1854/LU-8684795

- Akkerman, Stevo. “Het opbergen van Doedel is een schandvlek, en dat mag de staat best eens hardop zeggen.” Trouw, February 5 (2021). https://www.trouw.nl/gs-b061f03c.

- Andeweg, Agnes. “Allegory as Historical Method, or the Similarities between Amsterdam and Albania: Reading Simon Gikandi’s Slavery and the Culture of Taste.” Early American Literature 54, no. 2 (2019a): 329–342. doi:10.1353/eal.2019.0032.

- Andeweg, Agnes. “Noem deze Rembrandt toch ‘Twee Amsterdammers’.” Trouw, June 15 (2019b). https://www.trouw.nl/gs-bf66070d.

- Assmann, Aleida. “Canon and Archive.” In Cultural Memory Studies: An International and Interdisciplinary Handbook, edited by Astrid Erll and Ansgar Nünning, 97–107. Berlin/New York: De Gruyter, 2008.

- Bijl, Paul. “Colonial Memory and Forgetting in the Netherlands and Indonesia.” Journal of Genocide Research 14, no. 3–4 November 1 (2012): 441–461. doi:10.1080/14623528.2012.719375.

- Bindman, David, Henry Louis Gates, Karen C.C. Dalton , eds. The Image of the Black in Western Art: Pt. 1. From the ‘Age of Discovery’ to the Age of Abolition: Artists of the Renaissance and Baroque. Harvard: Harvard University Press, 2010.

- Essed, Philomena. Alledaags racisme. Amsterdam: Feministische Uitgeverij Sara, 1984.

- Essed, Philomena. Understanding Everyday Racism: An Interdisciplinary Theory. Newbury Park: Sage, 1991. Accessed May, 19 2021. http://catdir.loc.gov/catdir/enhancements/fy0655/91022025-t.html

- Gikandi, Simon. Slavery and the Culture of Taste. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011.

- Hathaway, Yulia. “‘They Made Us into A Race. We Made Ourselves into A People’: A Corpus Study of Contemporary Black American Group Identity in the Non-Fictional Writings of Ta-Nehisi Coates.” Corpus Pragmatics 5, no. 3 March 2 (2021): 313–334. doi:10.1007/s41701-021-00101-8.

- Hondius, Dienke. “Black Africans in Seventeenth-Century Amsterdam.” Renaissance and Reformation/Renaissance et Réforme 31, no. 2 (2008): 87–105. doi:10.33137/rr.v31i2.9185.

- Jeurgens, Charles, and Michael Karabinos. “Paradoxes of Curating Colonial Memory.” Archival Science 20, no. 3 September 1 (2020): 199–220. doi:10.1007/s10502-020-09334-z.

- Kolfin, Elmer. “Rembrandt’s Africans.” In The Image of the Black in Western Art: Pt. 1. From the ‘Age of Discovery’ to the Age of Abolition: Artists of the Renaissance and Baroque, edited by David Bindman, Henry Louis Gates, and Karen C.C. Dalton, 271–306. Harvard: Harvard University Press, 2010.

- Martin, Ben L. “From Negro to Black to African American: The Power of Names and Naming.” Political Science Quarterly 106, no. 1 (1991): 83–107. doi:10.2307/2152175.

- “Mauritshuis paste ‘gevoelige’ namen al aan.” AD.nl, 10 December 2015. https://www.ad.nl/den-haag/mauritshuis-paste-gevoelige-namen-al-aan~a4279b0d/.

- Meijer, Maaike, and Bernadette van Dijck. “Zwijgen zal ons niet beschermen: Gesprek met Audre Lorde, zwarte dichteres en lesbisch feministe.” Lust & gratie 1, no. 4 (1984): 6–25.

- Nick, I.M. “Black Rising: An Editorial Note on the Increasing Popularity of a US American Racial Ethnonym.” Names 68, no. 3 July 2 (2020): 131–140. doi:10.1080/00277738.2020.1787613.

- Ponte, Mark. “1656: Twee mooren in een stuck van Rembrandt.” In Wereldgeschiedenis van Nederland, edited by Lex Heerma van Voss, 265–269. Amsterdam: Ambo/Anthos, 2018a.

- Ponte, Mark. “‘Al de swarten die hier ter stede comen’: Een Afro-Atlantische gemeenschap in zeventiende-eeuws Amsterdam.” TSEG - The Low Countries Journal of Social and Economic History 15, no. 4 (2018b): 33–62. doi:10.18352/tseg.995.

- Raaijmakers, Ilse. De stilte en de storm: 4 en 5 mei sinds 1945. Zutphen: Walburg Pers, 2018.

- “Rembrandt, Twee Moren, 1661 gedateerd.” Accessed 19 May 2021. www.rkd.nl/explore/images/2956.

- Rigney, Ann. “Portable Monuments: Literature, Cultural Memory, and the Case of Jeanie Deans.” Poetics Today 25, no. 2 June 20 (2004): 361–396. doi:10.1215/03335372-25-2-361.

- Rigney, Ann. “Plenitude, Scarcity and the Circulation of Cultural Memory.” Journal of European Studies 35, no. 1 (2005): 11–28. doi:10.1177/0047244105051158.

- Said, Edward W. Orientalism. New York: Vintage Books, 1979.

- Said, Edward W. Culture and Imperialism. London: Vintage Books, 1994.

- Stoler, Ann Laura. Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2009.

- “Structures of Feeling.” Oxford Reference. Accessed 4 June 2021. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803100538488.

- “Sywert van Lienden sluisde 9 miljoen euro naar persoonlijke holding.” Follow the Money - Platform voor onderzoeksjournalistiek, 31 May 2021. https://www.ftm.nl/artikelen/sywert-van-lienden-sluisde-9-miljoen-euro-naar-persoonlijke-holding.

- “Twee Afrikaanse Mannen.” Accessed 19 May 2021. https://www.mauritshuis.nl/nl-nl/verdiep/de-collectie/kunstwerken/twee-afrikaanse-mannen-685/.

- Van Stipriaan, René. “Dutch Dealings with the Slavery Past: Contexts of an Exhibition.” In Sensitive Pasts: Questioning Heritage in Education, edited by Carla van Boxtel, Maria Grever, and Stephan Klein, 92–108. New York, Oxford: Berghahn Publishers, 2016.

- Wekker, Gloria. White Innocence: Paradoxes of Colonialism and Race. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016.

- Wekker, Gloria. Witte onschuld: Paradoxen van kolonialisme en ras. Translated by Menno Grootveld. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2017.

- Williams, Raymond. The Long Revolution. London: Penguin, 1961.

- Williams, Raymond. Border Country. New York: Horizon Press, 1962.

- “Zwarte schrijfster.” De waarheid, 18 July 1984.