ABSTRACT

Increasing numbers of UK students now seek mental health support while at university. Clear evidence for the best configuration of student support services is lacking. Most service evaluations have focused on counselling – with little evaluation of low-intensity support services such as non-clinical mental health and well-being teams or student accommodation welfare support. This qualitative study addresses that gap, examining student and staff experiences of new well-being advisers in academic departments and halls of residence at one UK university in 2018, marking a step-change in welfare support delivery. Using reflexive thematic analysis with data collected in 40 focus groups and interviews approximately 18 months after service launch, five themes were identified: Trusted Friend; Joined Up Approach; Proactive versus Reactive; Belonging; and My University Cares. The well-being advisers offered timely, low-intensity support as an accessible, approachable addition to academic, clinical and online provision. However, evidence showed operational challenges such as data-sharing between academic, professional and support service staff. The volume of students seeking support also appeared to compromise resource intended for preventative and community-building work, particularly in student accommodation. Concerns remained for students who do not seek help, with findings underlining the importance of issues of belonging, connection and representation in relation to well-being support. Notably, this highly visible well-being investment appeared to shift a negative cultural narrative which was undermining student and staff confidence to one of greater reassurance of support. Our conclusions have implications for student support service configuration and emphasise the importance of a whole university well-being approach.

Introduction

Growing numbers of university students are seeking mental health support, in part due to increasing levels of mental health problems in the general population, widening participation policies, and greater levels of awareness (Bould et al. Citation2019; Hubble and Bolton Citation2020; Lipson et al. Citation2022). Research suggests more than a third (35%) of students both nationally and internationally may have experienced a common mental health disorder at some point in their lives (Bennett et al. Citation2022; Bruffaerts et al. Citation2019). Students also face unique stressors: academic, financial and domestic challenges alongside social changes such as leaving home, forming relationships, greater opportunities for use of recreational drugs or alcohol, potential sleep disruption and for some, study combined with employment or caring roles (Duffy et al. Citation2019; Student Minds Citationn.d.). The heightened focus in the UK on student mental health has been mirrored in increasing pressure for academic staff in pastoral roles and a rising demand for university support services (Hughes et al. Citation2018; Thorley Citation2017).

In response, UK institutions have diversified their mental health and well-being provision over the last decade (Broglia, Millings, and Barkham Citation2018; RCPsych Citation2021). Today’s higher education (HE) support models vary considerably depending on local context and include: student health and counselling services, specialist, clinical mental health advisers (non-clinical) mental health or well-being teams, disability and international student advisers, accommodation welfare teams, academic tutors, peer mentors and online/phone support (Piper Citation2017; Pollard et al. Citation2021, 43; RCPsych Citation2021, 47).

Evidence suggests short-term counselling is effective for students facing mental health challenges, however it is resource-intensive, often has long waiting-lists, and is not always appropriate (Biasi et al. Citation2017; Broglia et al. Citation2021). Pastoral support offered by academic tutors is generally highly valued by students but relies on staff capacity for an increasing welfare responsibility alongside relevant training and personal skills (Hughes et al. Citation2018). There are now a growing number of embedded ‘mental health advisers’ or ‘well-being teams’ in UK universities, often tasked with responsive student support as well as preventative psychosocial education or community building effort (Pollard et al. Citation2021, 50). However, to date there has been an absence of evidence for the specific impact or effectiveness of these roles (Broglia, Millings, and Barkham Citation2018; Sampson et al. Citation2022). There is a similar lack of peer-reviewed evidence for welfare support in university-managed student accommodation (Piper Citation2017).

Growing numbers of HE studies now use qualitative or mixed research methods for their ability to offer valuable detail of lived experience, e.g. student perception of the role of university support services (Priestley et al. Citation2022; Remskar et al. Citation2022); well-being in student accommodation (Worsley, Harrison, and Corcoran Citation2021); or racial inequalities and barriers to student support (Arday Citation2018; Stoll et al. Citation2022). Here, we address the knowledge gap regarding low-intensity student well-being services with a comprehensive qualitative case-study evaluating a major investment at a large UK university in September 2018 (Ames Citation2022, 207). This paper examines the impact and process of introducing new well-being advisers in academic departments and halls of residence as perceived by students and staff, 15–24 months after service launch.

Methods

Setting and intervention

The current research took place in a university in South West England where in 2018/19 there were almost 27,000 students and 6,000 staff. A fifth of the institution’s students were international (20%), over a quarter were from Black, Asian and minority ethnicity backgrounds (27%), and almost three-quarters were undergraduates (74%). More than 8,000 (mostly first-year) students lived in halls of residence (both university and privately run) situated across the city. Between 2016 and 2018 this particular institution had been at the centre of highly publicised national concerns about growing levels of student mental health difficulties and wait-times for student counselling services (ChaffinCitation2018). In the academic year 2018/19 it committed an extra £1 million pounds to its annual mental health budget, creating more than 25 non-clinical well-being adviser roles across academic departmentsFootnote1 (Ames Citation2022, 212). In parallel, welfare support was restructured in the university-run student accommodation from a traditional warden modelFootnote2 to a professionalised 24/7 residential well-being adviser model (Residence Life) operating out of three central campus hubs see .

The new stepped careFootnote3 model was designed to relieve pressure on academic, professional and clinical staff and tackle downstream issues by addressing student concerns early before they spiralled into mental health difficulties, and to deliver new preventative well-being initiatives for all students (Ames Citation2022, 212). It was aligned with a ‘whole university’ organisational approach to well-being first advocated by Universities UK in 2017, and more recently in the UK’s Student Mental Health Charter (Hughes and Spanner Citation2019; UUK Citation2020). A single access point to student support (Wellbeing Access) was also introduced in 2019/20,Footnote4 offering a streamlined online/telephone service staffed 24/7 by the new advisers, with initial triage of student need (using an online contact form) before support was allocated.

Design

This qualitative study examined staff and student testimony using Braun and Clarke’s updated reflexive thematic analysis approach (Braun and Clarke Citation2006, Citation2021b). It took a critical realist and contextualist perspective, i.e. transparent acknowledgement that participants and researchers bring their own ‘worldview’ to data, and similarly that research is necessarily shaped by cultural context and timing (Bhaskar Citation2010; Braun and Clarke Citation2021c, 179; Pilgrim Citation2014). The first author’s (JB) background is cisgender, white British, first generation at university, mother of teenagers, and mature student/researcher at the institution evaluated here. The co-authors were independent of design and delivery of the new service model but academics at the same university.

Study topic guides (examples in Supplementary File-Appendix A) were developed in collaboration with staff, clinicians and a student advisory group in line with the UK’s Student Mental Health Charter co-production principles (Hughes and Spanner Citation2019, 65). They contained semi-structured questions including: overall perception of the new services; understanding of what they did; contact and experience of using or working with services; and general feedback about what worked well and what could be changed.

The current study contributed to a broader mixed-methods evaluation of the new service introduction which included population surveys and well-being service-use data (Bennett Citation2023) – further papers in progress. By taking advantage of a natural experiment in situ, we adopted a flexible approach to process and impact evaluation, supported by the latest Medical Research Council complex intervention guidance (Skivington et al. Citation2021). Ethical Approval for the study was granted in May 2019 by the Institution’s Health Sciences Committee (Ref: 85483).

Participants and procedure

Current staff and students were recruited to focus groups and interviews in the academic year 2019/20 using purposive, then snowball sampling methods (Ritchie et al. Citation2014). Recruitment invitations went out in the autumn and spring terms in staff newsletters, student email and via social media. A-priori sampling criteria were used to generate a final sample of students and staff with a broad range of experience and backgrounds, informed by Malterud et al. (Citation2016)’s concept of information power, i.e. information richness across a dataset (see ). Student focus group participants were not required to have used the new services, but student interviewees needed to have personal experience of contacting a well-being adviser. The lockdown disruption associated with the COVID-19 pandemic (which closed UK university campuses in March 2020) meant fieldwork was initially carried out face to face on campus (4 focus groups and 12 interviews) and subsequently via video-links (9 focus groups and 15 interviews). Sessions were 30–80 minutes depending on group size and availability. Participants gave written consent, a distress protocol was in place for potential issues arising from the sensitive subject matter, and all data were fully anonymised. Students received a £20 voucher as renumeration for their time.

Table 1. Stakeholder focus groups.

Sample characteristics

Thirteen focus groups were carried out between January and September 2020 to include different stakeholder perspectives – see . Overall, there was a gender balance in both staff and student focus groupsFootnote5 – one exception was the postgraduate focus group which was predominantly female.

Twenty-seven one-to-one interviews were carried out between December 2019 and July 2020. More than half of the student interviewees were female (n = ~17) with only one participant explicitly identifying as non-binary – however participants were never directly asked about their gender status. Almost a third of interviewees were from a minority ethnicity background, and three students referred in their interview to having a disability. Student characteristics also differed by fee-status (home n = 19, EU/international n = 8); course level (undergraduate/foundation/exchange n = 19, postgraduate n = 8); residence (halls n = 19, private accommodation n = 8); year of study (first year n = 15, other n = 12); study discipline (arts n = 5, engineering n = 2, health sciences n = 5, life sciences n = 5, science n = 4, social sciences and law n = 6).

In total, forty hours of narrative data captured the views and experiences of 120 students and staff studying or working at the university between 2017/18 and 2019/20.

Analysis

Focus groups and interview transcripts were coded and developed into themes (initially by first author) using NVivo-12 software, mind-maps and reflexive notes (Braun and Clarke Citation2021c; QSR International Pty Ltd Citation2020). The analysis was inductive, identifying shared patterns of conceptual meaning in the narrative data without making explicit or explanatory theoretical assumptions (Braun and Clarke Citation2021a, Citation2021c, 157). Coding and thematic ideas were then explored reflexively and collaboratively with co-authors and other stakeholders (Student and Well-being Steering groups) in an iterative and recursive process which ensured thematic development remained rooted in the data (Braun and Clarke Citation2019, 594). Analyses concentrated on higher-level themes independent of any ongoing material changes in service delivery, transcending what might be temporary features or conflation with COVID-19 disruption.

Results

Thematic findings

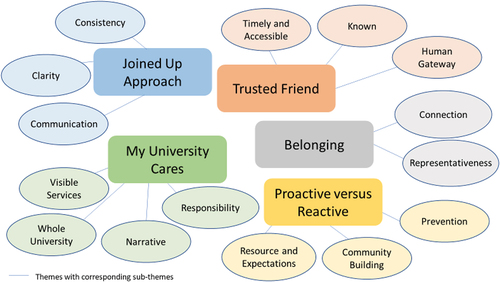

Five themes were identified in relation to the impact and experience of using or working with the new well-being services: ‘Trusted Friend’, ‘Joined Up Approach’, ‘Proactive versus Reactive’, ‘Belonging’ and ‘My University Cares’ (see ). Each spanned a number of sub-themes, which are highlighted in bold and referred to in more detail in Supplementary File - Appendix B.

Trusted friend

The new well-being advisers appeared to offer a valued support resource in addition to existing academic, clinical and online university support. In both academic departments and halls of residence they were described as ‘professional but informal’ and useful for ‘practical advice’.

I just had one session [with Residence Life] … and it was really helpful. It was a very friendly and kind of informal atmosphere … I was mainly discussing my family problems that are happening right now … she [also] sent me … videos and instructions on … different techniques to kind of calm myself down. Home Undergraduate First Year Humanities.

Students (and staff) experienced the new services as offering timely and accessible well-being support, with almost all interviewees describing a ‘fast’ response, and several stressing the importance of simple, immediate and 24/7 contact.

I prefer to go somewhere that’s quicker because sometimes you just need someone to talk to, like as quickly as possible. For the moment … just someone. Home Undergraduate First Year Arts.

Another friend had done it and it was quite helpful for her … I looked online and found it really easily, the system, and emailed through. Home Undergraduate First Year Dentistry.

As well addressing the issue of long wait-times for clinical appointments, the professionalised well-being role appeared to tackle further known barriers to accessing support such as student concerns about documentation, unwillingness or inability to speak to academics or family and friends, or simply not knowing where to find help:

I didn’t tell my personal tutor because I felt it would offend him because it was his department, so I told Residence Life. International Undergraduate First Year Social Sciences.

The students find it really overwhelming like to try and know what support is available and where do they go for what … a huge part of our role is like a link … I think that’s been quite useful for students. Well-being Adviser.

Advisers appeared to offer a ‘friendly’ and ‘approachable’ route to initial help and information, and a human gateway to further support if needed.

It was basically like making my life easier really … she was doing bits for me and gave me good advice in terms of whether I should go to my GP … it was just someone I also trusted … ’ Home Undergraduate Third Year Sciences.

Many students agreed it was useful in the first instance to have ‘someone’ to talk to who could offer advice, and who ‘listened’:

I very much saw them as a signposting service with the added bonus that they were actually human beings with sympathy. Home Undergraduate Third Year Economics.

The advisers were also seen as a welcome addition for ‘creating positive relationships on the ground with students’ (University GP), as well as a valuable resource for other staff as ‘familiar’ known faces who were specifically tasked with well-being issues.

It’s kind of reassuring to the students that, “oh we have a person in our halls, they know what they’re doing, they’ll help us”. Home Undergraduate First Year Veterinary Science.

We were dealing with - you know, high suicide risk and everything and there was nowhere to go, except for referring them to a student counselling service that had something like an eight-week waiting list just to be seen at one point … Even just that shared responsibility is a huge weight off our shoulders. Student Administrative Manager.

Nonetheless, several academic tutors and administrators stressed the continued importance of their relationships with students as a ‘first point of contact’ for well-being issues. There was broad consensus that all university staff still need to have the skills, resource and training to support students.

I think personal tutors definitely need more training in that regard if they are to continue being a pastoral as well as academic care. Home Undergraduate Year Two Life Sciences.

[We all] feed into the well-being of the student, not just Well-being services. We all have an impact on making their life good here. International Student Team Staff.

Conversely, there was also a concern that a ‘centralised service means a less personal service’, particularly in halls of residence where without live-in wardens (who had been greater in number), fewer ‘familiar faces on campus’ could lead to greater isolation for first years, or vulnerable students who do not seek help and those who might not be identified in other ways.

The students who ask for help are rarely students that need the most help … it’s the ones that don’t ask … you have to pick it up in other ways. Student Support staff.

That was supported by considerable evidence that despite increased support service visibility, some students were still unwilling or too unwell to actually seek help:

The hard part is reaching out, because I know there are lots of nice people out there who can give you that advice and just talk to you…It’s just about the student connecting with the services. Home UG First Year Medicine.

Joined up approach

‘Joined Up Approach’ reflects the complexity of integrating a new support tier into a large established university system with evidence of ongoing challenges in internal processes between student-facing university staff.

“It doesn’t seem to be very joined up”. Lecturer in sciences

Initially, a lack of clarity around the new service role seemed to make the university support system harder to navigate for staff working alongside it, ‘Should I be directing them to Residence Life or Well-being?’ (Academic Tutor). For many students with complex needs that also sometimes meant being ‘bounced around the system’.

It seems pretty impressive from the outside, but I feel like sometimes for more serious issues you can get caught up in a bureaucratic struggle to reach somewhere helpful. International Undergraduate Third Year Science.

However, most participants acknowledged it was ‘early days’ for the new model, and evidence from later focus groups and interviews suggested that ‘Wellbeing Access’ - the one point of access system introduced in 2019/20, was already simplifying pathways for students seeking support:

I found that you literally went on to Student Well-being … you fill out a form … it was, tell us how you’re feeling, what’s going on and we’ll suggest what you need. Home Undergraduate First Year Science.

[Wellbeing Access] is the best solution in terms of students knowing exactly where to go and exactly what to do. So, one telephone number, one online form, one email address as the gateway to all Well-being Services, is a positive thing’. Residence Life Adviser.

However, some staff felt that despite new professionalised welfare provision, there was still no consistency of support:

… it’s more impactful in some halls than it is in others. Students’ Union Adviser.

Others acknowledged that consistency of welfare provision was difficult across a large institution with diverse departmental cultures, but believed the new advisers were an improvement on the previous model, particularly in halls of residence.

… it seems so much more professional, so much more healthier and boundaried … it was so patchy, so patchy and now it is consistent, I think. Student counsellor.

Despite recognition that change management is a dynamic process, the launch of the services was also seen by some staff and students as ‘rushed’ and lacking thorough consultation. Critically, there was a clear perception that ongoing communication between different departments and services involved in supporting students could be improved.

Obviously their service [new wellbeing service] is an iterative process, and we understand that- but they’ve never communicated to us what the iterations are. So, we’re trying to advise students on how to use their service and then students will come back to us and say “oh they say they don’t do that”. Student Support Staff.

This separation between Residence-Life and academics … There is all manner of stuff going on over there [in halls] and then it manifests itself in the department in whatever way and we have no warning … the flow of information between academic and non-academic faces in the university is not very good. Academic Tutor.

Communication across the university was closely linked to concerns about information sharing and General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Issues regarding student privacy and data-sharing, and any potential legal consequences for ‘getting it wrong’ were evidenced in every staff group. Staff repeatedly discussed referring students to well-being services but being left ‘in limbo’, with no information about whether the student was then being supported, leaving them uncertain if they were still holding risk.

… the confidentiality issues are so terrifying for staff that they will not alert anybody else unless they absolutely have to. We don’t have a whole-university system. There is no operational system to make sure that everybody concerned with an individual student is kept up to date… Senior Academic.

The challenges were further underlined by some student participants who were clear about keeping their personal issues completely separate from ‘the university’ as they saw it – with implications for university staff liaising with well-being advisers. It is an issue that clinicians already encounter:

Whatever system you have, you would need to be able to flex with two very different types of presentations to preserve a person’s confidentiality … a right to just come and study on a course but not have the uni know anything about what’s going on for them, or [have the uni] involved if they want to. Student Counsellor.

Proactive versus reactive

‘Proactive versus Reactive’ describes a tension in the dual ambition for the new well-being advisers to provide both non-clinical responsive student support as well as prevention or outreach work e.g. workshops and community building events.

Testimony suggested the intervention was making a ‘positive difference’, but adviser resource had been ‘overwhelmed’ in responding to student need, compromising expectations for the model to also offer proactive/preventative effort, particularly in halls of residence.

I think we were probably taken aback a little bit by the number of students coming forward with quite complex issues to deal with … You can’t turn someone away and say I am sorry I can’t see you because I am doing a pizza night in ten minutes … Residence Life Adviser.

One student counsellor believed the ‘opening of the floodgates’ was due to increased visibility of support services, ongoing external pressures such as reduced NHS services and more students coming to university with pre-existing mental health issues.

I think a lot of the time … we’re still seeing things happen, and then reacting. So, the preventative work, it’s really challenging to do that [after] students come to university, there’s more work that’s got to be done prior … Every service I’ve ever worked in [this field], if you increase the capacity, you increase the service users. Student Counsellor.

A senior tutor called it ‘stemming the tide’:

… the university is committing itself to providing a service that it can’t really sustain. Academic Tutor.

For some, refining the model was a solution:

I think that clear separation between reactive provision and community building needs to be made with maybe two separate teams, I think would make things a lot easier. Students’ Union Administrator.

For others, particularly advisers in halls of residence, it also meant a more clearly defined model:

It matters in terms of whether we are promoting Residence Life as a model, because Residence Life is a particular type of service [i.e., preventative models] which I think in the UK some universities are developing … so are we that or are we student support? Residence Life Adviser.

At individual level, ongoing prevention and management of existing cases appeared to be a key strength of both services. It was very evident advisers (especially in halls of residence) were regularly ‘following up’ and ‘keeping an eye’. At the same time, well-being advisers in academic departments were seen as starting to deliver on psychoeducational workshops.

[Well-being] did a really good workshop for our students, just specifically for the under 18s on culture shock and homesickness … It was great. Administration Manager.

Yet, advisers in halls appeared under greater strain, arguably due to their wider remit i.e. dealing with welfare, accommodation and disciplinary issues, out-of-hours (24/7), and community building events. While almost all student participants valued Residence Life as ‘responsive’, the conflict with community building resource was apparent:

For our [student committee] they were terrible … and we couldn’t really put on any events for our halls at all. But as a student using them [for mental health], they were great. I called them up and they came over straight away and they sorted me out’. Home Undergraduate Second Year Psychology.

Critically, the wider impact of less preventative and community building work was seen as having potential for a more detrimental long term effect, leading to poorer outcomes and more welfare cases in future.

… like the whole idea was proactive community building will reduce reactive welfare provision but that hasn’t happened on the ground. In order to make it a success that’s something I think that needs to change’. Students’ Union Staff.

Belonging

‘Belonging’ reflected the ability of the new services to facilitate connection between students, staff and the wider university community and to be representative of the student body, inclusive, and culturally competent.

Social connections in a community where students feel ‘safe’, ‘part of’, and ‘valued’, were seen as important for well-being, particularly in transition from home to university. Isolation and loneliness appeared intrinsically tied to later well-being service use. For example, these students described a difficult and ‘isolated’ start which led them to seek adviser support:

I could see lots of other people who had flatmates, and they were doing everything together … then in my accommodation, I just used to go back, and … I didn’t really have anyone. Home Undergraduate First Year Medicine.

… there’s so much stuff, so much new things that you’re interacting with … people are doing a lot of drugs and a lot of drinking. I think it’s a time where there’s always going to be a lot of mental health problems. At school … you have got these close relationships with everyone, and you just don’t have that anymore … Home Undergraduate Fourth Year Geography.

Many of the students interviewed had experienced problems in their living environment. Some faced challenges with drug use, sexual harassment or homophobia – but many more experienced social problems such as flat-share relationships, disruption or privacy issues, causing enough stress to need well-being support:

… it wasn’t a very well distributed hall, so it became very bitchy very quickly, and it was quite difficult for some of us. Home Undergraduate First Year Humanities.

I found my roommates are really nice, but I could not tolerate the noise outside … I could hear people talking really loud at midnight … I couldn’t concentrate myself on my academic study and … found myself not in a good state to make friends … and it’s my first time to be in the UK. International Masters First Year Accounting.

Representativeness was also key for students seeking help. Students (and staff) did not always feel well-being support services were accessible to them as individuals, or reflected or understood their specific needs, and that in turn affected their feeling valued and part of the university community. Linked to ‘consistency’ of service provision, there was a perception that well-being support could often be aimed at white, home undergraduates, failing to cater for a demographically diverse student body. Similarly, there were questions about whether a centralised service would always be limited in its ability to understand the nuance and demands of different academic disciplines, halls of residence, or even the differences for undergraduates and postgraduates across a large organisation.

It is insane because it’s one in two postgrads suffer from mental health issues. Whereas it’s one in three in the whole population. But there’s nothing specific to look after postgrads. Home Final Year Postgraduate Health Science.

Issues of representation and barriers to using the services were especially common for students who had added social, cultural or language challenges. Critically that also influenced how likely some students were to seek support:

It is not acceptable to have mental health issues where she’s from. So, she’s come here with all of this support … and she didn’t know what to do. That’s consistently seen across particularly Chinese students … there is a cultural barrier for them to access the service. Centre Administration Manager.

Despite evidence for ongoing cultural barriers, it was also clear that things were also starting to change and improve.

I realised a lot of my black friends might have an undiagnosed disorder, but they’ve never really given it much thought, because obviously at home there’s quite a bit of stigma around mental health – no one really talks about it. Whereas here, it might be a space to find out actually what you’re going through is normal. International First Year Undergraduate Engineering.

I had a student say they went and spoke to a Well-being adviser and they weren’t culturally competent, but they were actually able to recognise that and signpost them to someone else. Student Administrator.

… so I think [the university] are trying very hard to support LGBT groups and different kind of awareness months and appreciating different cultures which I definitely have not seen as much at other universities. Home Undergraduate First Year Science.

My university cares

‘My University Cares’ captures the broader significance of cultural and organisational narrative, highly visible support services, a holistic approach to university well-being, and the boundaries of institutional responsibility for supporting student mental health.

Narrative appeared to have an important influence on both student (and staff) perception of well-being support. Ongoing negative media coverage for this institution and ensuing ‘word of mouth’ appeared to have eroded confidence in seeking or giving help.

I had heard before coming to university certain things about mental health at [institution]… that was actually one concern my parents had for me. Home Undergraduate First Year Law.

I was having a bit of a struggle … but I just thought that after hearing stories [about difficulties seeking help] that it was just going to be a goose chase … I just thought no, I won’t do it. Home Undergraduate Third Year Politics.

I think we’re very aware of the problem [suicide prevention], we’re very sort of… I would say, nervous of it…which takes its toll. University GP.

Almost all participants agreed the service introduction had facilitated a positive shift in the university mental health narrative and wider reputation.

It feels there’s a different culture around mental health at the university. I can’t explain it … I feel like it’s taken seriously … I feel like it’s a different culture which makes you feel more heard. Home Masters Fourth Year Life Sciences.

The new investment meant highly visible services and regular support ‘nudges’ i.e. emails, posters, face to face talks promoting the well-being advisers had led to improved student (and staff/parents) trust and confidence.

They make it quite clear where the support is and where you can get help, which was really comforting actually. International Undergraduate First Year Engineering.

People are having positive experiences and they are sharing that with their friends and their fellow students and the personal tutors, and its reputation has grown quite quickly. Well-being Adviser.

However, many staff and students stressed that new support services alone cannot address growing mental health challenges in universities, and any investment and change needs to be mirrored in whole university features, e.g. pedagogy, wider university culture, and staff well-being.

‘It’s bigger than student well-being ... ’ Student Administrator

… what are the structural things which are actually creating an environment which isn’t conducive to positive well-being in the first place? Home Undergraduate Third Year Economics.

It’s the grand irony of the well-being service that has got no well-being for its staff. Residence Life Adviser.

There was also an understanding that well-being support is not a limitless resource, and its role was part of a wider debate about mental health responsibility, the ‘in loco parentis’ role and student as a consumer.

How much support do we give? Is it supposed to be a self-help… sometimes this service is over supporting students throughout their studies and then where does that fit in with the university ethos of … producing strong, independent, young people that can go into work and everything? Student Administration Manager.

“The university’s an easy target … I actually think that students have a much greater influence on each other’s mental health then the university ever can, so to put the blame on the university is, I think … defeatist. Then there’s the whole, well, “we spend nine grand a year, so everything should be perfect”. Home Undergraduate First Year English.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to evaluate the impact of low-intensity student well-being services in the UK (Broglia, Bewick, and Barkham Citation2021; Sampson et al. Citation2022). A year after well-being advisers were introduced, students and staff described university mental health support as more accessible and approachable, addressing well-documented support-seeking barriers in HE such as lack of available services and long wait times for clinical appointments (Batchelor et al. Citation2019; Broglia et al. Citation2021). The findings also support recent recommendations to create more well-being access points and improve signposting for students (Priestley et al. Citation2022; Remskar et al. Citation2022). Likewise, a highly visible, non-clinical route into services, with a single point of access (Wellbeing Access) triaging students to appropriate support, appeared to reduce another identified risk, that students might not seek help until their difficulties are severe (Broglia, Millings, and Barkham Citation2017). Advisers also filled a previous gap, offering additional professional support for short-term problems such as exam stress or homesickness – potentially preventing progression to more serious problems (Ames Citation2022, 219). However, the new services were dependant on student engagement, amplifying concern that a responsive well-being advisory model cannot reach vulnerable students who do not seek help at all. It echoes trends seen in the wider literature that some of the most at-risk students do not present to services (Eisenberg, Golberstein, and Gollust Citation2007; Linton et al. Citation2022; McLaughlin and Gunnell Citation2020).

Operational challenges are not uncommon in complex organisational change as existing systems adapt (Hawe, Shiell, and Riley Citation2009). Our findings showed clarity and communication had a critical influence in both service launch and ongoing service delivery. This echoes a recurrent theme in the broader literature that clarity of responsibility and procedure across universities as well as in information-sharing is critical in relation to supporting students (Barden and Caleb Citation2019, 36; Hughes and Spanner Citation2019, 68). HE has been tackling issues of GDPR, rights to privacy and data-sharing for many years, yet our findings also indicate the complexities of how and what information is shared can be a key problem, and that a lack of a central data-sharing platform or clearer procedures can elevate perceived risk for all involved (Barden and Caleb Citation2019, 36; Dept of Health Citation2021; Linton et al. Citation2022). Our findings re-emphasise the difficulties for academics and other professional staff who sit on the periphery of service case-management systems but are still often at the frontline (Hughes Citation2021; Hughes and Bowers-Brown Citation2021). This supports a ‘whole university’ case for ongoing attention to the academic welfare role combined with suitable mental health training for all student-facing employees, as well as consideration of staff well-being (Cage et al. Citation2021; Payne Citation2022). It is also in line with the importance of ‘cohesiveness’ of well-being support across the HE provider – another key theme of the UK Student Mental Health Charter, supporting the whole university, holistic approach to institutional well-being (Hughes and Spanner Citation2019, 68).

In successfully ensuring well-being support became more accessible and approachable, the pro-active (preventive activities/community-building) element of the model appeared compromised. A need to prioritise reactive service delivery over prevention work is not uncommon in mental health care (Fazel Citation2016); however, existing research shows community building effort is important to address cultural barriers, facilitate connection, inclusivity, a sense of belonging and community, particularly in student halls of residence in smoothing first year transition from home to university life (Cage et al. Citation2021; Piper Citation2017; Worsley, Harrison, and Corcoran Citation2021). With no academic evaluation of implementation, impact or effectiveness for other UK student accommodation support models we cannot compare the challenges here, but our findings indicate the dual nature of the job may not have been working.

A final important understanding was that a negative institutional mental health narrative appeared to have shifted with the new advisers’ introduction, improving student confidence in university support provision and creating a greater sense of shared risk and responsibility for staff. It suggests the particular media attention given to this university may have contributed to a self-fulfilling negative cycle of socially transmitted information, i.e. ‘my university doesn’t care’ and ‘we are not okay’, leading here to increased student (and staff/parental) stress, and even preventing some students from seeking help. Similar social influence is seen in cases of disproportionate media focus such as vaccine safety or reporting of suicide, often having lasting detrimental effects on communities (Morley et al. Citation2020; Niederkrotenthaler et al. Citation2020). ‘Highly visible’ investment alongside frequent communication and promotion for the new well-being services, appeared to have been the catalyst for change, as a vehicle for ‘nudging’ or influencing student, staff and public views (Fadlallah et al. Citation2019; Hinyard and Kreuter Citation2007; Vlaev et al. Citation2016). It underlines the importance of both positive communication (internal and external) at every level across institutions, and the influence of leadership and visible strategic policy (Priestley et al. Citation2022).

Nevertheless, there was also general acknowledgement that well-being support investment is not a panacea. In line with the wider ‘whole university’ approach, staff and student testimonies clearly pointed to an ongoing need for strategic consideration across pedagogy, acceptable behaviour policies, accommodation allocation, and broader public health areas such as physical, financial, cultural and social domains (Hughes and Spanner Citation2019; UUK Citation2020). Similarly, with calls for explicit well-being strategies to equip students for their futures, as well as greater clarification and transparency of what mental health support a university can and should reasonably offer, our findings echo a critical and ongoing sector debate about mission, ethos and responsibility in higher education, which is as yet unresolved (Barden and Caleb Citation2019, 26).

Strengths and limitations

This study offers some of the first evidence for the impact of low-intensity university well-being services in a large sample of staff and students from a wide range of roles and backgrounds in a UK university (Sampson et al. Citation2022). Our reflexive, critical realist and collaborative design offers analytic transparency and detailed insight, responding to calls for more appropriate use of a reflexive thematic approach as well as ensuring stakeholder co-production (Braun and Clarke Citation2021a; Hughes and Spanner Citation2019).

Nevertheless, there are limitations. Pandemic disruption and material service changes during the fieldwork may have influenced student and staff perception and recollection of the speed and availability of support in ways we have not considered. Without further research, we cannot know if any perceived improvements were ongoing or transitory features of system change. Likewise, this study was only able to examine perceptions, we cannot demonstrate quantifiable impact on mental health among those who used the services; however, we do examine changes in population level mental health outcomes in a wider evaluation (Bennett Citation2023). As with all single-site case studies, these findings may not generalise to other institutions with different support frameworks and socio-geopolitical contexts, nevertheless they do offer general insights for the sector (Pollard et al. Citation2021; Thompson et al. Citation2022).

Implications and future research

Our findings underline the potential importance of low-intensity responsive and preventative university well-being support, and highlight the broader challenges faced by student welfare models. Policy frameworks call for authentic institutional engagement with student well-being issues, and this study offers evidence for the wider cultural impact that investment can have in a university setting (Hughes and Spanner Citation2019; UUK Citation2020). Literature examining the effectiveness of university mental health and accommodation welfare teams is some of the scantest in the HE sector- and while we have started to address that here, it needs greater attention (Bennett Citation2023; Osborn et al. Citation2022; Sampson et al. Citation2022). Evidence suggests non-clinical mental health advisers are now the second largest form of support in many university services (Broglia, Millings, and Barkham Citation2018; RCPsych Citation2021); the absence of empirical research comparing the outcomes of different support models is especially troubling in light of significant budgetary implications for institutions. Universities need to prioritise research evaluation when implementing support interventions to inform good practise across the sector. The current qualitative study would benefit from repeating, to assess investment reach and sustainability across the longer term and to understand how university support provision may have changed after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusions

This research addresses the gap in the higher education literature examining the role of university mental health and well-being teams. It demonstrates how a low-intensity model of student support can be valuable alongside academic, clinical or online support. It also underlines the importance of careful consideration how well-being support service models are configured, such as separation of responsive and preventative well-being effort. In addition, this work illustrates that institutional communication and demonstrable strategic engagement with mental health issues can have direct and positive consequences for student and organisational culture. Nevertheless, it underscores previous concerns that responsive services are unlikely to pick up students who do not seek help and that preventative and community building effort is imperative to prevent downstream mental health issues. This work also re-emphasises the importance of a whole university approach, and that support services cannot work in isolation of broader pedagogical, social and even societal concerns.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (33.7 KB)Acknowledgments

We thank all those staff and students who shared their personal experience for this study and those who contributed time and expertise to help design, recruit and comment on findings, including our student PPI and Well-being Steering group, clinicians and well-being staff.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2024.2335379

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Institution was made up of 25 academic schools in 2017/18 which are organised into six broader disciplines known as faculties: Arts, Engineering, Health Sciences, Life Sciences, Science, Social Science and Law.

2. Wardens were academic staff living in its (approximately 30) halls of residences, providing oversight and pastoral care in return for subsidised accommodation and expenses, alongside their teaching and research commitments. They were supported by a team of senior student residents.

3. Stepped care refers to a model in which a less resource intensive intervention is delivered first (P. Bower and S. Gilbody Citation2005).

4. One Point of Access was introduced during the research period.

5. Staff characteristics (other than role or academic department) were not collected.

References

- Ames, M. 2022. “Supporting Student Mental Health and Wellbeing in Higher Education.” In Preventing and Responding to Student Suicide: A Practical Guide for FE and HE Settings, edited by S. Mallon and J. Smith, 208–223. London: Jessica Kingsley.

- Arday, J. 2018. “Understanding Mental Health: What Are the Issues for Black and Ethnic Minority Students at University?” Social Sciences 7 (10): 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7100196.

- Barden, N., and R. Caleb. 2019. Student Mental Health and Wellbeing in Higher Education: A Practical Guide. London: Sage.

- Batchelor, R., E. Pitman, A. Sharpington, M. Stock, and E. Cage. 2019. “Student Perspectives on Mental Health Support and Services in the UK.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 44 (4): 483–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2019.1579896.

- Bennett, J. 2023. A ‘whole university’ approach to improving student mental health and wellbeing: Mixed-methods evaluation of a new university wellbeing service [ Doctoral dissertation], University of Bristol. https://research-information.bris.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/353366998/PhD_Bennett_Jacks_0953193_final_redacted.pdf.

- Bennett, J., J. Heron, D. Gunnell, S. Purdy, and M.-J. Linton. 2022. “The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Student Mental Health and Wellbeing in UK University Students: A Multiyear Cross-Sectional Analysis.” Journal of Mental Health 31 (4): 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2022.2091766.

- Bhaskar, R. 2010. Reclaiming Reality: A Critical Introduction to Contemporary Philosophy. London: Routledge.

- Biasi, V., N. Patrizi, M. Mosca, and C. De Vincenzo. 2017. “The Effectiveness of University Counselling for Improving Academic Outcomes and Well-Being.” British Journal of Guidance & Counselling 45 (3): 248–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2016.1263826.

- Bould, H., B. Mars, P. Moran, L. Biddle, and D. Gunnell. 2019. “Rising Suicide Rates Among Adolescents in England and Wales.” The Lancet 394 (10193): 116–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31102-X.

- Bower, P., and S. Gilbody. 2005. ”Stepped care in psychological therapies: access, effectiveness and efficiency”. The British Journal of Psychiatry 186 (1): 11–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12470.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2019. “Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 11 (4): 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2021a. “Can I Use TA? Should I Use TA? Should I Not Use TA? Comparing Reflexive Thematic Analysis and Other Pattern‐Based Qualitative Analytic Approaches.” Counselling and Psychotherapy Research 21 (1): 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12360.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2021b. “Conceptual and Design Thinking for Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Psychology 9 (1): 3. https://doi.org/10.1037/qup0000196.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2021c. Thematic Analysis a Practical Guide. edited by A. Maher. 1st ed. London: Sage.

- Broglia, E., B. Bewick, and M. Barkham. 2021. ”Using rich data to inform student mental health practice and policy”. Counselling & Psychotherapy Research 21 (4): 751–756. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12470.

- Broglia, E., A. Millings, and M. Barkham. 2017. “The Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms (CCAPS‐62): Acceptance, Feasibility, and Initial Psychometric Properties in a UK Student Population.” Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy 24 (5): 1178–1188. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2070.

- Broglia, E., A. Millings, and M. Barkham. 2018. “Challenges to Addressing Student Mental Health in Embedded Counselling Services: A Survey of UK Higher and Further Education Institutions.” British Journal of Guidance & Counselling 46 (4): 441–455. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2017.1370695.

- Broglia, E., G. Ryan, C. Williams, M. Fudge, L. Knowles, A. Turner, G. Dufour, A. Percy, M. Barkham, and S. C. O. R. E. Consortium. 2021. “Profiling Student Mental Health and Counselling Effectiveness: Lessons from Four UK Services Using Complete Data and Different Outcome Measures.” British Journal of Guidance & Counselling 51 (2): 204–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2020.1860191.

- Bruffaerts, R., P. Mortier, R.P. Auerbach, J. Alonso, A.E. Hermosillo De la Torre, P. Cuijpers, K. Demyttenaere, D.D. Ebert, J.G. Green, and P. Hasking. 2019. “Lifetime and 12‐Month Treatment for Mental Disorders and Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors Among First Year College Students. e1764.” International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 28 (2). https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1764.

- Cage, E., E. Jones, G. Ryan, G. Hughes, and L. Spanner. 2021. “Student Mental Health and Transitions Into, Through and Out of University: Student and Staff Perspectives.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 45 (8): 1076–1089. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2021.1875203.

- Chaffin J. 2018. UK universities act to tackle student mental health crisis. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/8e53ee5a-1e13-11e8-aaca-4574d7dabfb6

- Dept of Health. (2021). Guidance Information Sharing and Suicide Prevention: Consensus Statement. Department of Health.https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/271792/Consensus_statement_on_information_sharing.pdf.

- Duffy, A., Kate E.A. Saunders, G.S. Malhi, S. Patten, A. Cipriani, S. H. McNevin, E. MacDonald, and J. Geddes. 2019. “Mental Health Care for University Students: A Way Forward?” The Lancet Psychiatry 6 (11): 885–887. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30275-5.

- Eisenberg, D., E. Golberstein, and S.E. Gollust. 2007. “Help-Seeking and Access to Mental Health Care in a University Student Population.” Medical Care 45 (7): 594–601. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e31803bb4c1.

- Fadlallah, R., F. El-Jardali, M. Nomier, N. Hemadi, K. Arif, E.V. Langlois, and E.A. Akl. 2019. “Using Narratives to Impact Health Policy-Making: A Systematic Review.” Health Research Policy and Systems 17 (1): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-019-0423-4.

- Fazel, M. 2016. “Proactive Depression Services Needed for At-Risk Populations.” The Lancet Psychiatry 3 (1): 6–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00470-8.

- Hawe, P., A. Shiell, and T. Riley. 2009. “Theorising Interventions as Events in Systems.” American Journal of Community Psychology 43 (3–4): 267–276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-009-9229-9.

- Hinyard, L.J., and M.W. Kreuter. 2007. “Using Narrative Communication as a Tool for Health Behavior Change: A Conceptual, Theoretical, and Empirical Overview.” Health Education & Behavior 34 (5): 777–792. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198106291963.

- Hubble, S., and P. Bolton 2020. Support for Students with Mental Health Issues in Higher Education in England. House of Commons Library: Briefing paper, Number 8593. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-8593/.

- Hughes, G. 2021. “The Challenge of Student Mental Well-Being: Reconnecting Students Services with the Academic Universe.” In Student Support Services, 1–23. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-3364-4_6-2.

- Hughes, G., and T. Bowers-Brown. 2021. “Student Services, Personal Tutors, and Student Mental Health: A Case Study.” Student Support Services 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-3364-4_23-2.

- Hughes, G., M. Panjwani, P. Tulcidas, and N. Byrom. 2018. Student Mental Health: The Role and Responsibilities of Academics. Student Minds. http://www.studentminds.org.uk/uploads/3/7/8/4/37845/84/180129_accessible_version_studet_mental_health_the_role_ and_experience_of_academics_student_minds.pdf.

- Hughes, G., and L. Spanner. 2019. The University Mental Health Charter. Leeds: Student Minds.

- Linton, M.-J., L. Biddle, J. Bennett, D. Gunnell, S. Purdy, and J. Kidger. 2022. “Barriers to Students Opting-In to Universities Notifying Emergency Contacts When Serious Mental Health Concerns Emerge: A UK Mixed Methods Analysis of Policy Preferences.” Journal of Affective Disorders Reports 7:100289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadr.2021.100289.

- Lipson, S.K., S. Zhou, S. Abelson, J. Heinze, M. Jirsa, J. Morigney, and A. Patterson. 2022. “Trends in College Student Mental Health and Help-Seeking by Race/Ethnicity: Findings from the National Healthy Minds Study, 2013–2021.” Journal of Affective Disorders 306:138–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.03.038.

- Malterud, K., V.D. Siersma, and A.D. Guassora. 2016. “Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies: Guided by Information Power.” Qualitative Health Research 26 (13): 1753–1760. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315617444.

- McLaughlin, J.C., and D. Gunnell. 2020. “Suicide Deaths in University Students in a UK City Between 2010 and 2018 – Case Series.” Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention 42 (3): 171–178. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000704.

- Morley, J., J. Cowls, M. Taddeo, and L. Floridi. 2020. “Public Health in the Information Age: Recognizing the Infosphere as a Social Determinant of Health.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 22 (8): e19311. https://doi.org/10.2196/19311.

- Niederkrotenthaler, T., M. Braun, J. Pirkis, B. Till, S. Stack, M. Sinyor, U.S. Tran, M. Voracek, Q. Cheng, and F. Arendt. 2020. “Association Between Suicide Reporting in the Media and Suicide: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” BMJ: British Medical Journal 368:m575. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m575.

- Osborn, T.G., S. Li, R. Saunders, and P. Fonagy. 2022. “University students’ Use of Mental Health Services: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” International Journal of Mental Health Systems 16 (1): 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-022-00569-0.

- Payne, H. 2022. “Teaching Staff and Student Perceptions of Staff Support for Student Mental Health: A University Case Study.” Education Sciences 12 (4): 237. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12040237.

- Pilgrim, D. 2014. “Some Implications of Critical Realism for Mental Health Research.” Social Theory & Health 12 (1): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1057/sth.2013.17.

- Piper, R. 2017. Student Living: Collaborating to Support Mental Health in University Accommodation. London: Student Minds. http://www.studentminds.org.uk/uploads/3/7/8/4/3784584/student_living_collaborating__to_support_mental_health_in__university_accommodation.pdf.

- Pollard, E., J. Vanderlayden, K. Alexander, H. Borkin, and J. O’Mahony. 2021. Student Mental Health and Wellbeing: Insights from Higher Education Providers and Sector Experts. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/he-student-mental-health-and-wellbeing-sector-insights.

- Priestley, M., E. Broglia, G. Hughes, and L. Spanner. 2022. “Student Perspectives on Improving Mental Health Support Services at University.” Counselling and Psychotherapy Research 22 (1). https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12391.

- QSR International Pty Ltd. (2020). NVivo–12 (released in March 2020). https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home.

- RCPsych. (2021). Mental Health of Students in Higher Education, CR231. Royal College of Psychiatrists. Accessed June 5. https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/improving-care/better-mh-policy/college-reports/mental-health-of-higher-education-students-(cr231).pdf.

- Remskar, M., M.J. Atkinson, E. Marks, and B. Ainsworth. 2022. “Understanding University Student Priorities for Mental Health and Well-Being Support: A Mixed-Methods Exploration Using the Person-Based Approach.” Stress & Health 38 (4): 776–789. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.3133.

- Ritchie, J., J. Lewis, C.M. Nicholls, and R. Ormston. 2014. Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Sampson, K., M. Priestley, A.L. Dodd, E. Broglia, T. Wykes, D. Robotham, K. Tyrrell, M.O. Vega, and N.C. Byrom. 2022. “Key Questions: Research Priorities for Student Mental Health.” British Journal of Psychiatry Open 8 (3): 8(3. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2022.61.

- Skivington, K., L. Matthews, S.A. Simpson, P. Craig, J. Baird, J.M. Blazeby, K.A. Boyd, N. Craig, D.P. French, and E. McIntosh. 2021. “A New Framework for Developing and Evaluating Complex Interventions: Update of Medical Research Council Guidance.” BMJ: British Medical Journal 374:n2061. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n2061.

- Stoll, N., Y. Yalipende, J. Arday, D. Smithies, N.C. Byrom, H. Lempp, and S.L. Hatch. 2022. “Protocol for Black Student Well-Being Study: A Multi-Site Qualitative Study on the Mental Health and Well-Being Experiences of Black UK University Students.” BMJ Open 12 (2): e051818. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051818.

- Student Minds. (n.d.). What We Do. Student Minds. Accessed May 17, 2022. https://www.studentminds.org.uk/whatwedo.html.

- Thompson, M., C. Pawson, A. Delfino, A. Saunders, and H. Parker. 2022. “Student Mental Health in Higher Education: The Contextual Influence of “Cuts, Competition & comparison”.” British Journal Education Psychology 92 (2). https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12461.

- Thorley, C. 2017. Not by Degrees: Improving Student Mental Health in the UK’s Universities. Institute for Public Policy Research [IPPR]. https://www.ippr.org/publications/not-by-degrees.

- UUK. (2020, May 18). Stepchange: Mentally Healthy Universities. Universities UK. https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/what-we-do/policy-and-research/publications/stepchange-mentally-healthy-universities.

- Vlaev, I., D. King, P. Dolan, and A. Darzi. 2016. “The Theory and Practice of “Nudging”: Changing Health Behaviors.” Public Administration Review 76 (4): 550–561. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12564.

- Worsley, J.D., P. Harrison, and R. Corcoran. 2021. “The Role of Accommodation Environments in Student Mental Health and Wellbeing.” BMC Public Health 21 (1): 573. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10602-5.