When I was asked to write this piece on the future of archaeology in Australia, I contemplated outsourcing the task to AI, as I thought this would encapsulate through practice the future of our discipline. Happily, however, the text ChatGPT produced was so formulaic as to re-invigorate my faith in the future of our discipline as a human-centred creative enterprise. While AI has already demonstrated that it holds an ever-expanding position in archaeology, especially in remote sensing (e.g. Argyrou and Agapiou Citation2022), but also in site dating (Reese Citation2021), ceramic classification (Pawlowicz and Downum Citation2021), detection (Agapiou et al. Citation2021) and shell midden analysis (Bickler Citation2018), to name but some of the initial areas, I see it positioned as a tool at our disposal, rather than as a threat to our practice as it is the involvement of people which makes our discipline meaningful. Cultural and archaeological significance are both founded upon connections between the people of today and the people of the past. Archaeology, without people, is not archaeology. This has always been the case, but the growth of AI has thrown this into high relief.

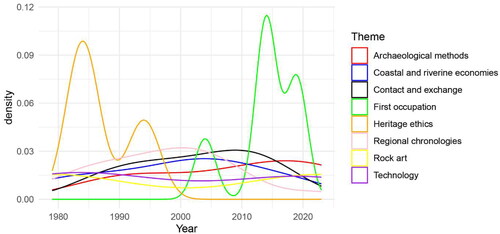

It is with this reminder—that human experience and connection are central to our discipline—that I’d like to contemplate the past, present and future of archaeology in Australia. A review of the first issue of Australian Archaeology (1974) highlights how enduring key research topics have been through the last 50 years. The ‘causes, nature and rate of change’ of the long history of First Nations’ adaptation to this continent, including timing of initial occupation, waves of occupation, technological and artistic changes, the use of fire in landscape management, the introduction of the dingo, external trade and contact into the historic period and agriculture, were all topics of interest in the 1970s (White Citation1974) and remain relevant today. Similarly, the interest in conservation and protection of sites and a concern with empowering Indigenous voices and working in close co-operation with Aboriginal communities were all present in the first issues of Australian Archaeology (Golson Citation1975; Kelly Citation1975; Moore Citation1975; Stockton Citation1975; Sullivan Citation1975). graphs the eight most cited research themes over the last 50 years of Australian Archaeology. Six of the eight research themes have remained reasonably consistent over time, with only Heritage Ethics and First Occupation showing downward and upward trends respectively.

Figure 1. Density plot showing the change over time in research theme of the 50 most cited papers in Australian Archaeology from 1974 to 2023, calculated as the top-5 most cited articles in each 5-year period 1974–2024. Data from scopus (2000–2023) and Australian Archaeology journal table of contents (1974–1999).

What has changed over the last 50 years is our ability to approach these fundamental topics from new angles, using decolonisation practices combined with new methods and new evidence adding complexity and detail to our understanding of the past. However, while the centring of Indigenous values and agendas is now recognised as essential to archaeological practice, there is still a long way to go in decolonising the discipline. Perhaps we are ‘mid-step’ in the acknowledgement of communities’ rights to control their lands and their cultures (Langford Citation1983) as we work through issues around the right to speak, lateral violence and gate-keeping.

New approaches to fundamental topics have also come from new technologies; in the early days from radiocarbon and OSL dating, and more recently from DNA advances which have allowed re-examination of the timing and nature of first occupation. The introduction of new techniques and approaches creates a cyclical development of knowledge, where new technologies and new ways of working allow us to access new evidence to re-investigate enduring research themes. Unlike Allen and O’Connell (Citation2020:4), whose review of research into first occupation led them to conclude ‘that current research on this subject is discovering more and more about less and less’, I think the cyclical development of knowledge is leading to revolutions in understanding. It wasn’t that long ago that First Nations occupation was considered to have had a much shorter time span. The next revolution in thinking about the nature and timing of Sahul occupation will come from new DNA and dating evidence which has the potential to resolve differences between models that argue for an early and large founding group in Australia around 60–65ka and an out-of-Africa exodus date of around 50ka.

In this sense, the latest cycle in the development of archaeological knowledge, machine learning, is just the most recent in a long list of tools we have been adding to our ever-expanding tool kit over the last 50 years. Machine learning’s force currently lies in its ability to automate and outsource processes such as the construction of physical and virtual models, code, text, and big data analyses. All of this happens through the input of existing entities (by a person). The revolution will be in full swing when embodiment takes off and AI automates the addition of new entities, or new phenomena not previously visible to us in our world.

But, to return to my introductory point, if human input, connection and engagement are removed from the discipline, so too are their value and meaning. What to watch now is how the principles of decolonisation will influence the use of machine learning in archaeology. What waits to be seen is whether the accelerated use of machine learning will foster a splintering in the discipline between community-centred practice on the one hand, and practice centred on big-data and data analytics on the other, or whether a powerful hybridisation emerges which lets us connect datasets and new ideas in truly innovative ways.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Agapiou, A., A. Vionis and G. Papantoniou 2021 Detection of archaeological surface ceramics using deep learning image-based methods and very high-resolution UAV imageries. Land 10(12):1365.

- Argyrou, A. and A. Agapiou 2022 A review of artificial intelligence and remote sensing for archaeological research. Remote Sensing 14(23):6000.

- Allen, J.I.M. and J.F. O’Connell 2020 A different paradigm for the initial colonisation of Sahul. Archaeology in Oceania 55(1):1–14.

- Bickler, S.H. 2018 Prospects for machine learning for shell midden analysis. Archaeology in New Zealand 61(1):48–58.

- Golson, J. 1975 Archaeology in a changing society. Australian Archaeology 2(1):5–8.

- Kelly, R. 1975 From the ‘Keeparra’ to the ‘cultural bind’—An analysis of the Aboriginal situation. Australian Archaeology 2(1):13–17.

- Langford, R.F. 1983 Our heritage—Your playground. Australian Archaeology 16(1):1–6.

- Moore, D.R. 1975 Archaeologists and Aborigines: Some thoughts following the AAA symposium at ANZAAS 1975. Australian Archaeology 2(1):8–9.

- Pawlowicz, L.M. and C.E. Downum 2021 Applications of deep learning to decorated ceramic typology and classification: A case study using Tusayan White Ware from Northeast Arizona. Journal of Archaeological Science 130:105375.

- Reese, K.M. 2021 Deep learning artificial neural networks for non-destructive archaeological site dating. Journal of Archaeological Science 132:105413.

- Stockton, E. 1975 Archaeologists and Aborigines. Australian Archaeology 2(1):10–12.

- Sullivan, S. 1975 The State, people and archaeologists. Australian Archaeology 2(1):23–31.

- White, J.P. 1974 Man in Australia present and past. Australian Archaeology 1(1):28–43.