At the peak of the Last Glacial Maximum, global sea levels were as low as −130 m below current levels. Over time, sea levels rose, inundating 2 million km2 of the Australian continental landmass. As Australian archaeology moves forward, the submerged cultural landscapes of the continental shelf must be considered. Historically, underwater archaeology in Australia has been focused on shipwrecks and colonial periods. However, there is increasing interest in the deep time archaeology of submerged Indigenous landscapes because of their significance for a range of major research questions. There has been some important work in this space, including the first attempts to locate submerged Indigenous archaeology at the Cootamundra Shoals by Flemming (Citation1983), establishing the potential for submerged landscape archaeology in Murujuga by Dortch (Citation2002), efforts to characterise potential site preservation by Nutley (Citation2014), and the identification of the first two submerged Indigenous sites in Murujuga by the Deep History of Sea Country project team (Benjamin et al. Citation2020).

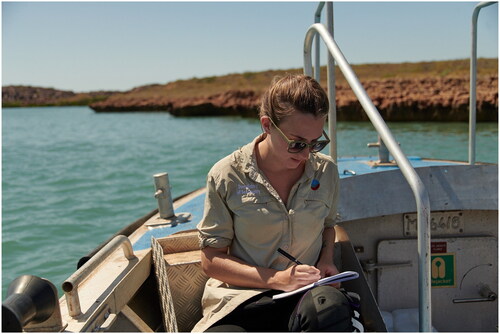

Over the course of my studies and postdoctoral research, I have had the privilege of working in Australia with Indigenous peoples on Sea Country, as well as engaging in international partnerships focused on understanding the deep human past and learning novel techniques through international projects, many of which can be applied in an Australian context. I was part of the dive team that located the first subtidal lithic artefacts in Murujuga during my PhD (). Prior to that discovery, I was trained on submerged archaeological sites in two of the world’s most established places for this subdiscipline: Denmark and Israel. In this reflection piece, I highlight the significance of submerged palaeolandscape archaeology for Australia and emphasise the importance of international collaborations for this research.

Figure 1. The author recording a survey log at Cape Bruguieres Channel in Murujuga during the Deep History of Sea Country project (Photograph: S. Wright).

Despite recent increased interest in this area, there remain sceptics who downplay the importance of the submerged archaeological record for understanding the human past and do not see the benefit of integration with the terrestrial record. Globally, the potential for submerged sites to contribute to archaeological research questions, in ways that are distinct from inland sites, has been demonstrated (see Bailey et al. Citation2020). In Australia, key questions regarding marine resource use, human dispersal, and adaptation to climate change cannot be addressed without understanding the now-submerged environment.

Maritime archaeology is often assumed to be expensive, and its value for money is consequently scrutinised. Undoubtedly, underwater archaeology can indeed be expensive, particularly in the context of large offshore projects. Expensive is, of course, a relative term, when considering societal priorities, resourcing, and research budgets. However, once projects are established, they can be relatively inexpensive, and cost-effective, particularly for nearshore fieldwork programs where research teams are well-trained and initial capital investment is in place. This is the case on the Carmel Coast of Israel, one of the global ‘hotspots’ for submerged landscape archaeology. There, snorkel surveys conducted at regular intervals throughout the year or following specific events (such as winter storms) are key to monitoring exposures of archaeological material on the seabed. More importantly, the submerged archaeological record provides insights that simply cannot be replicated by the terrestrial archaeological record. Many submerged sites found across the world exhibit exceptional preservation not commonplace in terrestrial archaeological contexts, providing the opportunity for unique finds to inform our truncated record of the past.

Without the incorporation of submerged environments, important questions in Australian archaeology will remain unanswered. For example, intense marine resource use is a phenomenon in Australia that is broadly associated with the Holocene, although there is also some evidence for marine resource use in the Late Pleistocene. It is possible that intense use of marine resources extends back to the Pleistocene but pre-high sea level stand sites, associated with past coastlines, are now submerged. To properly address questions of marine resource use in Australian archaeology, it is necessary to search for evidence that is now likely to be located offshore. At the same time, not all sites that are now found underwater must be assumed to be coastal sites. It is also possible that sites that focused on inland resources will be identified under water. In this way, submerged landscape archaeology is critical to address the antiquity of not just marine resource use in Indigenous Australian archaeology, but past resource and landscape use as a whole. The peopling of Australia and the subsequent movement of populations across the continent can also only be fully explored by investigating inundated cultural landscapes. The earliest archaeological sites in Australia would have formed on landscapes that are now under water. To identify these potential early sites, archaeologists must consider the submerged continental shelf.

Since people experienced dramatic environmental change in Australia, underwater sites may provide insights into human adaptation and resilience to climate change. This is crucial to understanding the long history of climate change and human responses to such change—understandings that are vital in order to face the challenges of modern climate change. This has been demonstrated globally and is likely to form a significant area for further research in Australia. The submerged archaeological record can be interrogated to discern how people responded to large-scale sea-level rise, including the wider impacts on their surrounding environments.

Because of the nature of the discipline, submerged landscape archaeology is at the forefront of the development of new techniques and models which can be applied more broadly. The development of remote sensing techniques allows for the mapping of vast areas of the seabed and may be used to identify high potential targets for ground-truthing. The use of machine learning and artificial intelligence may also contribute to submerged landscape archaeology. Remote sensing is valuable to submerged landscape archaeology, however, diver-based observations and ground-truthing are still critical to the discipline. There are some who suggest that the use of remote sensing and the development of predictive models is of limited value given that these models deal primarily with hypothetical sites and potential occupation locales (unless tested), but models do provide crucial guidelines for locating archaeological sites and may form a significant part of Australian archaeology moving forward.

Based on the work on submerged sites that has been carried out globally, Australian archaeologists have the potential to engage with and learn from international examples of research and management of submerged sites. There are thousands of sites in the Northern Hemisphere, and archaeological practice over time has developed to approach these sites. There is also the potential for comparative research. The preservation conditions for archaeological sites in locations such as Denmark and Israel may provide an opportunity to search for similar conditions where sites may be preserved in Australia. While submerged landscape archaeology is at an early stage in Australia, there is the potential to establish international partnerships that may benefit the development of Australian submerged landscape archaeology. Work undertaken by colleagues in the Americas provides an opportunity to work on submerged landscape studies within a colonial context, and where community engagement and cultural knowledge could offer insights and potential for cross-disciplinary approaches and comparisons.

While there are opportunities for international collaboration, there is also the potential for Australian archaeologists to collaborate more. Maritime archaeology and Indigenous archaeology have often been considered distinct entities, and have kept to their silos, with little overlap. Submerged landscape archaeology requires several subdisciplines to interact and cooperate, within archaeological communities, as well as with marine geosciences, anthropological communities and of course working in direct partnership with Traditional Owners. As the field progresses, maritime archaeologists will need to be trained to be chronologically unbound to any particular time period. Submerged landscape archaeology is an exciting and emerging research area in Australia, and it will be furthered by collaborative efforts in Australia and overseas. My own experience has shown the value of international collaboration in this space, and there will be no shortage of what we can both learn and teach through such partnerships with archaeologists willing to dive into the deep past.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Bailey, G., N. Galanidou, H. Peeters, H. Jöns and M. Mennenga (eds) 2020 The Archaeology of Europe’s Drowned Landscapes. Cham: Springer.

- Benjamin, J., M. O'Leary, J. McDonald, C. Wiseman … G. Bailey 2020 Aboriginal artefacts on the continental shelf reveal ancient drowned cultural landscapes in northwest Australia. PLoS One 15(7):e0233912.

- Dortch, C.E. 2002 Preliminary underwater survey for rock engravings and other sea floor sites in the Dampier Archipelago, Pilbara region, Western Australia. Australian Archaeology 54(1):37–42.

- Flemming, N.C. 1983 A survey of the late Quaternary landscape of the Cootamundra Shoals, north Australia: A preliminary report. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Diving Science Symposium of CMAS, pp.149–180. Padova: CMAS.

- Nutley, D. 2014 Inundated site studies in Australia. In A.M. Evans, J.C. Flatman and N.C. Flemming (eds), Prehistoric Archaeology on the Continental Shelf: A Global Review, pp.255–273. New York: Springer.