ABSTRACT

This study examined the nature of literature reviews published in Australian Social Work between 2007 and 2017. An audit was conducted to determine the number of reviews; types of reviews (systematic, meta-analysis, metasynthesis, scoping, narrative, conceptual, critical); and elements that were commonly reported (based on items drawn from the PRISMA checklist) including quality appraisal. A total of 21 reviews were identified. Results showed the overall number of reviews published remained relatively consistent across the decade. In relation to review types, systematic and scoping reviews appeared with greater frequency in more recent years. Most reviews reported significant proportions of the elements consistent with the type of review undertaken, although a minority did not report the search strategies and only one review included a quality appraisal. In conclusion, the reviews published over the last decade provide a strong foundation upon which further advances in the diversity and quality of reviews can be built.

IMPLICATIONS

Literature reviews are an indispensable tool for accessing knowledge to inform social work practice.

This first audit of literature reviews in Australian Social Work found a growing sophistication in the reviews published over the past decade.

Continued improvements in the design, conduct, and reporting of literature reviews will be an invaluable resource in equipping the profession to respond successfully to the growing complexity of demands placed on social work practice in the 21st century.

本文研究了 2007年到2017年间⟪澳大利亚社会工作⟫上发表的文献评述。作者统计了评述的数目、类型(系统、元分析、元综合、范围综述、叙事、概念、批判等)、常见要素(根据⟪棱镜⟫一览表的各项)。共发现21 种评述。发表的评述总数在过去十年中大致相当。就评述的类型而言,系统以及范围评述近些年有较高频率。大多数评述都有相当比例的要素与评述的类型相符合,不过也有少数未提到搜寻策略,仅有一个评述包含了质量的评定。总之是,过去十年发表的评述为将来提高评述的多样性和质量打下了坚实的基础。

Literature reviews are an important research method for exploring, distilling and evaluating the current published knowledge in a particular field. Specifically, a review shows the path of prior research and how that is linked to a current project or issue; integrates and summarises what is known in an area; and can be the stimulus for new ideas (Neuman, Citation2014). Reviews have value for several reasons. Summarising the literature around a topic (Alston & Bowles, Citation2012; Littell, Corcoran, & Pillai, Citation2008) has become increasingly important as the body of research publications within health and the social sciences has been increasing almost exponentially (Crisp, Citation2015; Littell et al., Citation2008). A review also helps to identify gaps in the literature which provide space to develop or test new ideas or interventions (Fawcett & Pockett, Citation2015). Moreover, the growing influence of evidence-informed practice has gone hand-in-hand with the expansion of reviews as a tool for advancement, with systematic reviews in particular employed to identify evidence for best practice in particular fields (Crisp, Citation2015; Littell et al., Citation2008). Schools of social work have a growing expectation that students in graduate research programs will conduct a literature review as a part of their training (Pickering & Byrne, Citation2014). Reviews are not restricted to empirical research, but also play an important role in advancing theory, and developing a conceptual and theoretical understanding around an issue. They can apply frameworks from critical theory to identify, investigate and highlight areas of inequality and oppression (e.g., Abdelkerim & Grace, Citation2012).

Given the value of literature reviews, it was important to identify the state of reviews published in Australian Social Work (ASW). ASW is a dynamic journal that reflects trends occurring both within the profession (nationally and internationally) (Bigby, Citation2010; McDermott, Citation2017) as well as the wider fields of health and social sciences research. In the broader literature, there has been a proliferation in the types of reviews. For example, a well-known typology has distinguished 14 different methodologies employed in conducting literature reviews (Grant & Booth, Citation2009). Some of these methodologies are recent developments (e.g., scoping reviews as developed by Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005), highlighting the dynamic nature of the science. So it would also be useful to examine whether an expanding range of review methodologies can be observed in ASW, in line with the growing methodological pluralism of research within the profession more generally (Shlonsky, Noonan, Littell, & Montgomery, Citation2011).

As the Cochrane and Campbell collaborations have spearheaded an increased sophistication and rigour of review methodology across health and the social sciences (Levin, Citation2001; Petrosino, Citation2013), this has had flow-on effects in the conduct of literature reviews more generally. Checklists have been developed to identify the essential elements that should be included in the report of reviews, with the goal of promoting greater transparency and accountability (Montgomery et al., Citation2013). One example is the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) checklist, which is now recommended by many journals as the benchmark for the reporting of reviews (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, Citation2009). Therefore, it is also important to examine which elements were commonly included in reviews reported within ASW.

One element of reviews that has been growing in importance is the quality (or critical) appraisal of studies included in a review. In quantitative research, the aim of quality appraisal is to ensure the internal validity of the review by ensuring that studies with a high risk of bias are not included (Higgins et al., Citation2011). Critical appraisal of qualitative studies is a more complex question, given the broad range of underlying epistemological approaches, goals of studies and methods employed. Despite these challenges, there has been a move towards the development of approaches to undertake the critical appraisal of qualitative evidence (Australian Journal of Social Issues, Citation2011; Carroll & Booth, Citation2015). Although quality appraisals are not a required element in every type of review, it is not known whether any of the reviews published in ASW have employed quality appraisal. The aim of the current study was to audit literature reviews published in ASW, with the objectives of determining: (i) the number reviews published; (ii) the types of reviews; (iii) which elements were commonly reported; and (iv) whether quality appraisal was included. The findings can support the design, conduct and reporting of literature reviews within ASW.

Methods

An audit was conducted of all articles published in ASW between 2007 and 2017, and involved four steps: identification of the concept; selection of studies; data extraction; and collating and summarising the results.

Identification of Concept

The audit focused on works in which the review was the sole purpose of the article. Articles which had a sub-section in the introduction titled “Literature review,” but the primary purpose of the article was to report on research findings, or articles in which the aim was twofold (e.g., an interview and a literature survey) were not included. The same criterion also helped distinguish theoretical papers from conceptual reviews. A theoretical paper explores a particular issue but without the explicit aim of canvassing the literature around that topic.

Selection of Studies

A database search employing search terms was not required for the audit. Instead, all material published in ASW from 2007 to 2017 was examined. The timeframe was chosen in order to focus on contemporary practice, rather than undertaking a historical survey. The audit was conducted between December 2017 and January 2018. The following inclusion criteria were applied: Original or Practice, Policy, & Perspectives (PPP) articles published in ASW; the word “review” was specified in the title, abstract, keywords or methods; the sole purpose of the paper was to undertake a review; the methods section contained some detail describing how the review was conducted. Other types of material published in ASW (i.e., editorials, book reviews, commentaries) were excluded.

An Excel-document was employed to record results from the initial screening of titles and abstracts. In some cases, the full text of the article was required in order to determine whether it met the inclusion or exclusion criteria. In cases of uncertainty, both authors independently examined the article, and came to a conclusion by consensus.

Data Extraction

Based on the work of Grant and Booth (Citation2009) and Coughlan and Cronin (Citation2017), seven distinct types of reviews applicable to social work research were distilled for the current study; (i) systematic review, (ii) meta-analysis, (iii) metasynthesis, (iv) scoping review, (v) critical review, (vi) conceptual review and (vii) narrative review.

Systematic reviews search in a structured and methodical order, often adhering to pre-registered protocols, to appraise and synthesise existing research to answer a specific research question and to find best evidence for practice (Grant & Booth, Citation2009). Meta-analysis is a set of statistical methods used to analyse and synthesise the results from quantitative studies on the same topic, to provide a precise effect of the results (Grant & Booth, Citation2009). Metasynthesis is “an interpretive synthesis of data, including phenomenologies, ethnographies, grounded theories and other integrated and coherent descriptions or explanations of phenomena, events or cases” (Bondas & Hall, Citation2007, p. 115). Scoping review is a defined and systematic process to explore the extent, range and nature of research activity (Levac, Colquhoun, & O’Brien, Citation2010) and identify gaps in the existing evidence base (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005), with results from initial searches leading to the modification or addition of additional search terms and strategies (Levac et al., Citation2010). Conceptual reviews aim to examine concepts in order to clarify their characteristics and to achieve a better understanding of the meaning of the concept (Coughlan & Cronin, Citation2017). Narrative review is a generic term for a literature review that can cover a wide range of subjects at various levels of completeness; it may or may not include comprehensive searching and typically employs a narrative-based synthesis (Grant & Booth, Citation2009). Critical reviews involve a thorough search and critical evaluation of the quality of literature around a topic (Grant & Booth, Citation2009). However, in sociology, a critical review applies critical theory to analyse and illuminate the political and ideological assumptions underlying existing literature addressing a particular issue, or to position a review within an emancipatory or anti-oppressive framework (e.g., Abdelkerim & Grace, Citation2012). This second meaning was employed in the audit.

A matrix was developed to describe which elements were reported in the conduct of the different types of reviews. The elements were drawn from the PRISMA checklist (Moher et al., Citation2009). Fourteen items were selected (). The elements were grouped into Title (identify the paper), Introduction (rationale, goal), Methods (eligibility criteria, information sources, selection criteria, data extraction, quality appraisal), Results (studies selected, study characteristics, present results), Discussion (summary of evidence, limitations, conclusions). The total number varied with the type of review: all 14 elements pertained to systematic reviews, whereas only seven elements were relevant for narrative, conceptual and critical reviews.

Table 1 Items adopted from PRISMA

Having developed the matrix, the first author then independently assessed the studies and allocated them to one of the seven categories. If the authors had specified the type of review, the article was allocated to that category. In six articles, the authors had not specified the type of review, and in these cases the review was classified by the first author. In cases of uncertainty, both authors checked the review and concluded by consensus.

The selected articles were then reviewed by the first author to identify which elements were reported, indicated by a Yes, No or Partly rating. If the appraisal was unsure, both authors independently assessed the article, and a consensus decision was made. In addition to the matrix, descriptive data were also collected on year of publication, the topic of the review and whether authors cited references for the review design.

Collating and Summarising the Results

To identify change in the frequency of reviews published, the audit timeframe was divided into two time periods and the number of reviews for each period calculated. Frequency data were generated for the focus of the review and review type. The types of reviews were also cross-tabulated against the two time periods.

Ratings on the elements (Yes, Partly, No) were entered into the matrix and tabulated. For ease of reporting, “Yes” and “Partly” were scored as “1” and “No” scored as “0”. The number of elements found to be present within each article was summed and compared (as a percentage) with the total number of possible elements. In addition, the elements most commonly present or most frequently absent across the different types of reviews were also identified.

Results

Number of Reviews

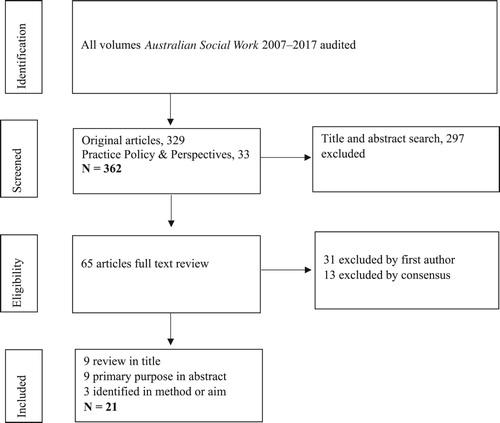

A total of 362 original articles and PPP papers were published in ASW over the audit period. The selection process is outlined in . A final set of 21 articles were selected.

Reviews comprised 5.8% (21/362) of all original articles and PPPs published in ASW between 2007 and 2017. Breaking the time frame into two time periods, 13 reviews were published between 2013 and 2017 (6.9%, 13/188) and eight between 2007 and 2012 (4.6%, 8/174). The review topics reflected a range of fields of practice ().

Table 2 Range of topics

Types of Reviews

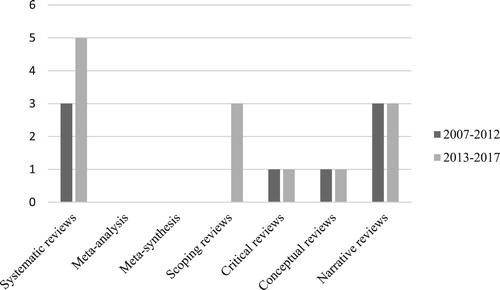

The two most common types of reviews were systematic (n = 8) and narrative reviews (n = 6). The remaining types of reviews were less commonly found (scoping reviews, n = 3; critical reviews, n = 2; conceptual reviews, n = 2). There were no examples of meta-analyses or metasynthesises. displays the mix of review types across the two time periods.

Elements of Reviews

provides a summary of the elements present across the 21 reviews. In presenting these data, the elements relevant to all review types will be reported first. This will be followed by a closer examination of the patterns across each of the different types of reviews.

Table 3 Matrix of items

Seven elements were common to all types of review, namely Title (including abstract and keywords), Introduction (2 items), Present results (item 11) and Discussion (3 items). The element relating to Title (i.e., the appearance of the word “review” either in the title, abstract, or keywords) was highly endorsed (20/21, 95%), although the word review only appeared once as a key word. Three other elements were also highly endorsed, namely Rationale (21/21, 100%), Present results (21/21, 100%) and Summary of evidence (20/21, 95%). Goal/aims (15/21, 71%) and Conclusions (16/21, 76%) were explicitly reported in approximately three quarters of the reviews. The one item that was endorsed in less than half of the reviews was Limitations (8/21, 38%).

Systematic reviews were judged on all 14 audit items. One of the reviews included all 14 elements; another three covered 13/14 items (93%); and one study covered 10/14 items (71%). The three reviews that scored 13/14 all missed the quality appraisal element. Finally, two reviews only covered half of elements (7/14 items; 50%), more consistent with a narrative review. In one of these cases the authors acknowledged they were undertaking a “less stringent, less detailed literature review methodology of a systematic review” (Abdelkerim & Grace, Citation2012, p. 107).

Two of the articles cited a methodology text that underpinned the review design. Abdelkerim and Grace (Citation2012) referenced a text by Torgerson (Citation2003). McPherson et al. (Citation2016) referenced a systematic review protocol, used previously by McCalman et al. (Citation2014) in an earlier systematic review (not published in ASW).

Only one review included a quality appraisal of the selected articles (Reed & Harding, Citation2015). The review examined the efficacy of family meetings in health settings for improving outcomes for clients, carers, and health systems. A validated 10-item scale designed to evaluate the methodological quality of randomised and non-randomised trials was used (Downs & Black, Citation1998), finding that all identified studies were of low or moderate quality in research design and delivery.

Scoping reviews, are a recent development in review methodology, and reflecting this, the three scoping reviews identified by the audit were conducted in the 2013–2017 time period. Quality appraisal is not a standard part of scoping reviews (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005; Levac et al., Citation2010), so the number of elements was based on 13 items. Generally, the scoping reviews incorporated most elements (two reviews 12/13 items, 92%; one review 8/13 (62%). The element most commonly missing was a description of the study characteristics (item 10). One article (Tilbury, Walsh, & Osmond, Citation2016) cited the seminal reference for scoping reviews (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005) as the basis for the design of their review.

Critical reviews, Conceptual reviews, and Narrative reviews do not require the same level of reporting of the methods as systematic or scoping reviews, and therefore were examined for the presence of seven elements (items 4–10 were not applicable). Three of the studies scored 6/7 items (86%), three 5/7 items (71%) and four 4/7 items (57%). One of the articles (Kiraly & Humphreys, Citation2013) although described by the authors as narrative, included a number of elements in the methods more in keeping with a systematic review.

Discussion

Approximately one in 20 original articles or PPPs published in ASW over the past 11 years were reviews. In relation to review types, systematic and scoping reviews appeared with greater frequency in more recent years, although the total number of reviews and limited time frame did not enable statistical tests to determine whether this represented a trend. Generally most reviews reported significant proportions of the possible elements consistent with the type of review undertaken.

The increasing diversity in the types of reviews published within ASW reflect the growing methodological pluralism observed more broadly within the profession (Shlonsky et al., Citation2011). The absence of meta-analyses was not unexpected, but given the strong qualitative research tradition represented within ASW (Simpson & Lord, Citation2015), the absence of any reviews undertaking a metasynthesis was more surprising. The methodologies associated with metasynthesis are continually evolving in their sophistication (Bondas & Hall, Citation2007; Lockwood, Munn, & Porritt, Citation2015) with journals such as Qualitative Health Care now publishing large numbers of such reviews.

The appearance of systematic reviews was encouraging. Systematic reviews play an important role in the synthesis of research in a way that is both transparent and rigorous and can be powerful tool to inform policy and practice around a given topic (Crisp, Citation2015; Gray, Joy, Plath, & Webb, Citation2013). As identified in this audit, systematic reviews can address a broad range of topics and study types, and do not simply focus on randomised controlled trials (Crisp, Citation2015). However, as with all review methodologies, it is important to be aware of both the strengths as well as the limitations of such reviews in informing knowledge or practice (Attanasio, Citation2014; Plath, Citation2006). The appearance of scoping reviews is also a positive development. Social workers often work and research in fields or on topics in which there may be little research (Shlonsky et al., Citation2011), and in such areas the exploratory approach of a scoping review is ideal.

There was a balance between reviews with more articulated methodologies (e.g., systematic or scoping reviews, n = 11) and the critical, conceptual and narrative reviews (n = 10). Although narrative reviews have limitations in their comprehensiveness, and in the reporting of the processes underlying study selection (Crisp, Citation2015; Grant & Booth, Citation2009), they have a role to play. They may be used in a broader perspective, having a more exploratory aim of capturing the overall knowledge of a field, theme, or theoretical understanding of a phenomenon. Moreover, conceptual or critical reviews are generally specialised applications of a narrative review methodology. Another reason for selecting a narrative review methodology can be logistic constraints such as limited time, resources, access to databases, and so forth (Crisp, Citation2015).

In relation to review nomenclature, a discrepancy was found between the descriptor and elements that were reported in some instances. For example, the review by Kiraly and Humphreys (Citation2013), although described as “narrative,” appeared to be more consistent with a systematic review methodology. Another two papers were “systematic” in approach (Brough, Wagner, & Farrell, Citation2013; Skouteris et al., Citation2011) but the review methodology was unspecified, in all three cases maybe underselling the rigour of the review. In contrast, three reviews may have overstated the extent to which they were systematic.

Documenting the elements reported in reviews is distinct from making judgements about the quality of reviews themselves (Shea et al., Citation2009). Although it is desirable that reviews are as comprehensive as possible in reporting elements highlighted in the matrix, many other factors come into play in making determinations about quality (e.g., the clarity of the research question, the validity of the individual studies incorporated into the review, the quality of the synthesis). However, the more thoroughness with which the review is reported, the easier it is to assess the overall quality (Moher et al., Citation2009).

It was notable that only one review incorporated a quality appraisal of the selected studies (Reed & Harding, Citation2015). There are a growing number of critical appraisal tools available for particular types of study designs (Katrak, Bialocerkowski, Massy-Westropp, Kumar, & Grimmer, Citation2004) which could be deployed in future reviews. In qualitative research, the notion of “quality appraisal” is more strongly contested, with arguments that the philosophical and epistemological diversity rules out the possibility of valid appraisal (Carroll & Booth, Citation2015; Dixon-Woods, Booth, & Sutton, Citation2007). Contrasting views have suggested the importance of establishing the quality of primary qualitative studies as a prequel to metasynthesis (e.g., Toye et al., Citation2013), and despite the challenges, there is a growing body of experience in undertaking appraisal of qualitative studies (Finfgeld-Connett, Citation2014; Hannes & Macaitis, Citation2012).

In considering the findings of this audit a number of limitations need to be considered. In developing the matrix, items were selected from the PRISMA checklist that were relevant to the reviews most commonly published in ASW. However, there may have been other elements that should have been included. Moreover, the type of review had to be inferred in some cases and may not have reflected the intention of the authors. Next, the appellation of “systematic” to reviews in the current audit may not meet more stringent definitions for systematic reviews adhered to elsewhere (Crisp, Citation2015). Finally, some reviews could have been classified in more than one category.

Looking to the future, there is room for explicitly labelled critical reviews and meta-syntheses. An increased focus on quality appraisal would also be invaluable. Few reviews referenced the methodology employed for the review, and this would be useful. More consistent use of review as a keyword could also strengthen the likelihood of the review being identified in literature searches.

In conclusion, the number of reviews has been relatively stable over the past decade. The greater proportion of systematic and scoping reviews in more recent years could represent a trend to an increasing sophistication, and the reviews published over the last decade provide a strong foundation for further advances in the diversity and quality of reviews. An enriched environment of reviews will make a significant contribution to growing the knowledge basis and evidence-informed practice within the profession.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Thomas Strandberg http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4578-0501

Grahame K. Simpson http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8156-9060

References

- Abdelkerim, A., & Grace, M. (2012). Challenges to employment in newly emerging African communities in Australia: A review of the literature. Australian Social Work, 65(1), 104–119.

- Alston, M., & Bowles, W. (2012). Research for social workers an introduction to methods. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8, 19–32.

- Attanasio, O. P. (2014). Evidence on public policy: Methodological issues, political issues and examples. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 42, 28–40.

- Australian Journal of Social Issues. (2011). Guidelines for the use of qualitative research material. Retrieved from http://www.aspa.org.au/publications/ajsi-qual-guidelines.htm

- Azri, S., Larmar, S., & Cartmel, J. (2014). Social work’s role in prenatal diagnosis and genetic services: Current practice and future potential. Australian Social Work, 67(3), 348–362.

- Bigby, C. (2010). Rankings, ratings, and reviews. Australian Social Work, 63, 371–374.

- Bondas, T., & Hall, E. O. (2007). Challenges in approaching metasynthesis research. Qualitative Health Research, 17(1), 113–121.

- Borrell, J., Lane, S., & Fraser, S. (2010). Integrating environmental issues into social work practice: Lessons learnt from domestic energy auditing. Australian Social Work, 63(3), 315–328.

- Brough, M., Wagner, I., & Farrell, L. (2013). Review of Australian health related social work research 1990–2009. Australian Social Work, 66(4), 528–539.

- Carroll, C., & Booth, A. (2015). Quality assessment of qualitative evidence for systematic review and synthesis: Is it meaningful, and if so, how should it be performed? Research Synthesis Methods, 6, 149–154.

- Coughlan, M., & Cronin, P. (2017). Doing a literature review in nursing, health and social care. London: Sage.

- Cox, R., Skouteris, H., Hemmingsson, E., Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M., & Hardy, L. L. (2016). Problematic eating and food-related behaviours and excessive weight gain: Why children in out-of-home care are at risk. Australian Social Work, 69(3), 338–347.

- Crisp, B. R. (2015). Systematic reviews: A social work perspective. Australian Social Work, 68(3), 284–295.

- Dellemain, J., & Warburton, J. (2013). Case management in rural Australia: Arguments for improved practice understandings. Australian Social Work, 66(2), 297–310.

- Dixon-Woods, M., Booth, A., & Sutton, A. J. (2007). Synthesizing qualitative research: A review of published reports. Qualitative Research, 7(3), 375–422.

- Downs, S. H., & Black, N. (1998). The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 52, 377–384.

- Fawcett, B., & Pockett, R. (2015). Turning ideas into research: Theory, design and practice. London: Sage.

- Finfgeld-Connett, D. (2014). Use of content analysis to conduct knowledge-building and theory-generating qualitative systematic reviews. Qualitative Research, 14(3), 341–352.

- Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26, 91–108.

- Gray, M., Joy, E., Plath, D., & Webb, S. A. (2013). Implementing evidence-based practice: A review of the empirical literature. Research on Social Work Practice, 23, 157–166.

- Hannes, K., & Macaitis, K. (2012). A move to more systematic and transparent approaches in qualitative evidence synthesis: Update on a review of published papers. Qualitative Research, 12(4), 402–442.

- Higgins, J. P., Altman, D. G., Gøtzsche, P. C., Jüni, P., Moher, D., Oxman, A. D., … Sterne, J. A. (2011). The Cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. British Medical Journal, 343, d5928.

- Hunter, S. V. (2008). Child maltreatment in remote Aboriginal communities and the Northern Territory emergency response: A complex issue. Australian Social Work, 61(4), 372–388.

- Katrak, P., Bialocerkowski, A. E., Massy-Westropp, N., Kumar, V. S., & Grimmer, K. A. (2004). A systematic review of the content of critical appraisal tools. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 4(1), 22.

- Kiraly, M., & Humphreys, C. (2013). Family contact for children in kinship care: A literature review. Australian Social Work, 66(3), 358–374.

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5, 69–78.

- Levin, A. (2001). The Cochrane collaboration. Annals of Internal Medicine, 135, 309–312.

- Littell, J. H., Corcoran, J., & Pillai, V. (2008). Systematic reviews and meta-analysis. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Lockwood, C., Munn, Z., & Porritt, K. (2015). Qualitative research synthesis: Methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 13(3), 179–187.

- Maple, M., Pearce, T., Sanford, R. L., & Cerel, J. (2017). The role of social work in suicide prevention, Intervention, and postvention: A scoping review. Australian Social Work, 70(3), 289–301.

- McCalman, J., Bridge, F., Whiteside, M., Bainbridge, R., Tsey, K., & Jongen, C. (2014). Responding to Indigenous Australian sexual assault: A systematic review of the literature. SAGE Open, 4(1), 1–13.

- McDermott, F. (2017). Celebrating 70 years and reflecting on the challenges ahead. Australian Social Work, 70(4), 387–391.

- McPherson, L., Atkins, P., Cameron, N., Long, M., Nicholson, M., & Morris, M. E. (2016). Children’s experience of sport: What do we really know? Australian Social Work, 69(3), 348–359.

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264–269.

- Montgomery, P., Grant, S., Hopewell, S., Macdonald, G., Moher, D., & Mayo-Wilson, E. (2013). Developing a reporting guideline for social and psychological intervention trials. British Journal of Social Work, 43, 1024–1038.

- Munro, A., & Allan, J. (2011). Can family-focussed interventions improve problematic substance use in Aboriginal communities? A role for social work. Australian Social Work, 64(2), 169–182.

- Murray, S., & Goddard, J. (2014). Life after growing up in care: Informing policy and practice through research. Australian Social Work, 67(1), 102–117.

- Neuman, W. L. (2014). Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Harrow: Pearson Education.

- O’Neal, P., Jackson, A., & McDermott, F. (2014). A review of the efficacy and effectiveness of cognitive-behaviour therapy and short-term psychodynamic therapy in the treatment of major depression: Implications for mental health social work practice. Australian Social Work, 67(2), 197–213.

- Ozanne, E. (2009). Negotiating identity in late life: Diversity among Australian baby boomers. Australian Social Work, 62(2), 132–154.

- Petrosino, A. (2013). Reflections on the genesis of the Campbell collaboration. The Experimental Criminologist, 8(2), 9–12.

- Pickering, C., & Byrne, J. (2014). The benefits of publishing systematic quantitative literature reviews for PhD candidates and other early-career researchers. Higher Education Research and Development, 33, 534–548.

- Plath, D. (2006). Evidence-based practice: Current issues and future directions. Australian Social Work, 59, 56–72.

- Reed, M., & Harding, K. E. (2015). Do family meetings improve measurable outcomes for patients, carers, or health systems? A systematic review. Australian Social Work, 68(2), 244–258.

- Robertson, M. (2008). Suicidal ideation in the palliative care patient: Considerations for health care practice. Australian Social Work, 61(2), 150–167.

- Shea, B. J., Hamel, C., Wells, G. A., Bouter, L. M., Kristjansson, E., Grimshaw, J., … Boers, M. (2009). Amstar is a reliable and valid measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62(10), 1013–1020.

- Shlonsky, A., Noonan, E., Littell, J. H., & Montgomery, P. (2011). The role of systematic reviews and the Campbell collaboration in the realization of evidence-informed practice. Clinical Social Work Journal, 39, 362–368.

- Simpson, G. K., & Lord, B. (2015). Enhancing the reporting of quantitative research methods in Australian Social Work. Australian Social Work, 68, 375–383.

- Skouteris, H., McCabe, M., Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M., Henwood, A., Limbrick, S., & Miller, R. (2011). Obesity in children in out-of-home care: A review of the literature. Australian Social Work, 64(4), 475–486.

- Tilbury, C., Walsh, P., & Osmond, J. (2016). Child aware practice in adult social services: A scoping review. Australian Social Work, 69(3), 260–272.

- Torgerson, C. (2003). Systematic reviews. London: Continuum.

- Toye, F., Seers, K., Allcock, N., Briggs, M., Carr, E., Andrews, J., & Barker, K. (2013). ‘Trying to pin down jelly’: Exploring intuitive processes in quality assessment for meta-ethnography. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 46.

- Trevor, M., & Boddy, J. (2013). Transgenderism and Australian Social Work: A literature review. Australian Social Work, 66(4), 555–570.

- Whelan, J., & Gent, H. (2013). Viewings of deceased persons in a hospital mortuary: Critical reflection of social work practice. Australian Social Work, 66(1), 130–144.

- Willis, P. (2007). “Queer eye” for social work: Rethinking pedagogy and practice with same-sex attracted young people. Australian Social Work, 60(2), 181–196.