ABSTRACT

Social workers play a pivotal role in addressing equity and diversity within Australia using both culturally responsiveness skills and knowledge. This article describes a research project that resulted in the development of the Continuous Improvement Cultural Responsive Tools that can be used by social workers in their practice. This was a large project conducted over three years, which involved engagement and consultation with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community social workers. The community engagement and consultation process included the provision of cultural governance and participation in interviews. The tools developed are linked to seven key domains (Ngurras) that aim to increase the skills, knowledge, and overall confidence of social work practitioners in their culturally responsive practice. This article discusses the tools that provide a clear structure to guide social workers’ critical engagement in becoming more culturally responsive social workers and individuals when working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples.

IMPLICATIONS

Social work practices need to address the social injustices faced by Aboriginal Peoples by becoming more culturall responsive.

The tools were developed to support social workers in their practice to self-assess their transformation in becoming culturally responsive social workers.

Continuous improvement in collaborative and culturally responsive social work will improve services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples.

Social workers are committed to addressing inequality through aiming for ethical practice, which requires holistic and critical thinking (Australian Association of Social Workers [AASW], Citation2012, Citation2013, Citation2016). There are various guidelines and frameworks to provide knowledge and skills around engaging and working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in practice (AASW, Citation2015; Zubrzycki et al., Citation2014). Social work curriculum aims to align practice with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander values, principles, and knowledge, thus creating a culturally responsive social work profession. Aboriginal social work research (Bennett, Citation2013, Citation2019; Bennett et al., Citation2011; Taylor et al., Citation2013) reported that social workers often felt ill-prepared and anxious about their abilities to work collaboratively and respectfully with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples and that many lacked the skills, knowledge, and values to provide culturally and professionally appropriate services. A literature review of over 30 similarly themed frameworks and publications (e.g., Bennett, Citation2003; Hertel, Citation2017; Mafile’o & Vakalahi, Citation2018; Muller, Citation2014) was completed by the researcher (first author) and a summary of the findings of this review follows.

Cultural Responsiveness

Cranney and Indigenous Allied Health Australia (Citation2015) emphasised that working in a culturally responsive way is about strength-based, action-oriented approaches, respect for all persons and in practice is service-user oriented. It includes respect for dignity, participation in choices, quality of amenities, access to social support networks and choice of provider (Dudgeon et al., Citation2014). The emphasis on culturally responsive practice with Indigenous Peoples is an essential component of any social work intervention, which then means unsafe cultural practice diminishes (Parker & Milroy, Citation2014).

Implications for Social Workers

Cultural responsiveness refers to the capacity of an individual to develop collaborative and respectful relationships with Indigenous Peoples and respond to the issues and needs of communities in ways that promote social justice and human rights (Zubrzycki et al., Citation2014). It aims to transform social workers’ understanding of themselves, their relationships with others, and their understanding of the interrelationships between power and the structures of race, class, and gender, so as to lead to an “envisioning of alternative approaches and possibilities for social justice” (Mackinlay & Barney, Citation2014, p. 65). A critical element of being culturally responsive is the recognition that knowledge is situated within and informed by historical, cultural, and social contexts (Bennett et al., Citation2018). This means social workers need to make critical shifts in their understandings of themselves and their practice contexts. This requires embracing the power of not knowing, sitting with uncertainty, and being willing to be challenged and shaped by these “different” ways of knowing (Bennett, Citation2015).

Cultural responsiveness requires social workers to move beyond simply being self-aware of their knowledge, values, and skills to moving to an awareness of the relationship between themselves, others, and the systems in which we interact (Bennett et al., Citation2018; Green et al., Citation2016). Social workers demonstrate cultural responsiveness by engaging in self-reflection and then responding appropriately to the uniqueness of the individuals with whom they are interacting (Green et al., Citation2016). Laird (Citation2008) contended that social workers need to “learn about other cultures to guard against ‘unintended racism’” (p. 39), transforming social work practice using an “anti-racist” praxis to rise beyond “individual interventions” to formulate collective strategies (Dominelli, Citation2018, p. 11). Daniel (Citation2008) contended that although mandated in social work education, little discussion has occurred about the kinds of knowledge needed to prepare social workers to work towards ending oppression and other forms of injustice in their actual work. The increasing need for culturally responsive social work professionals is more evident the more racial, ethnic, and cultural diversity occurs in society (Lee, Citation2013).

Benefits of Cultural Responsiveness in Social Work

Cultural responsiveness works towards improved outcomes through the integration of culture in service delivery (Centre for Cultural Competence Australia, Citation2021). Evidence shows that when there is a lack of cultural responsiveness, health and wellbeing outcomes are poorer. Therefore, for Aboriginal people, improving cultural responsiveness requires removal of the barriers that create inequitable care. Research suggests that providing culturally responsive service has the potential to lead to improved attendance at appointments and an improvement in following recommended treatment, which leads to increased safety, access, and equity for all groups (Stewart, Citation2006). Cultural responsiveness is important for all social and cultural groups, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples; people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds; refugees or displaced migrants; people at all life stages, including end of life; people with different abilities, including intellectual and cognitive disabilities; and people with gender and sexuality diversities (Green et al., Citation2016; Stewart, Citation2006).

Aims and Research Questions

The aim of the overall project was to develop culturally responsive tools specific to social workers, human services workers, and organisations that would support the commitment by the Australian Association of Social Workers to the process of reconciliation and improve the health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples across all social work fields of practice. The four interrelated questions that formed the basis of the research project were:

How would Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stakeholders evaluate and measure culturally responsive social work practice?

What would Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stakeholders regard as indicators of effectively integrated culturally responsive practice?

How are social workers understanding and integrating culturally responsive practice into their work?

How are social workers currently measuring and evaluating their culturally responsive social work practices?

Methodology

Indigenous Standpoint

Methodology is anchored in broader philosophies (values and beliefs) and epistemologies. For an Aboriginal academic, this means we build our methodologies on our own knowings, doings, and beings. We call this an Indigenous standpoint. The authors’ (BB’s and CM’s) Aboriginal ways of knowing, being, and doing were utilised to collate, measure, and assess culturally responsive social work practice (Rigney, Citation1999; Martin & Mirraboopa, Citation2003). Within this project, pragmatism allowed the researcher to flexibly engage with, and be led by, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voices and standpoints. This then ensured that the knowledge and tools developed within the project will best serve Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

Research Design

This project utilised Indigenous research methodologies (Martin, 2003; Moreton-Robinson, Citation2014; Nakata, Citation2007; Rigney, Citation1999; Walter & Andersen, Citation2013; Wilson, Citation2008). Within this framework, diverse methods were utilised within a sequential exploratory mixed-methods approach (Teddlie & Tashakkori, Citation2009). The methods prioritised Indigenous stakeholder interviews using Indigenous yarning (Bessarab & Ng’andu, Citation2010), semistructured interviews (Creswell, Citation2014) and Indigenous statistical research (Walter & Andersen, Citation2013). A pragmatic design (Rorty, Citation1999; Feilzer, Citation2010) incorporating three stages was used to explore the concepts of Aboriginal ways of knowing, being, and doing and how these concepts can be articulated into, and evidenced within, social work practice.

Participants

The project was represented by stakeholders representing various ages, gender, and countries of Australia, both urban and rural, including representatives from the Torres Strait Islands (see ). At all stages of the research, reciprocation was shown for stakeholder participation in the research in the form of gift certificates. Respectful community consultation was embedded into the first three stages of the project: design methodology, development, and delivery. Community consultation was important as the needs and requests of the community were prioritised.

Figure 1. Map of community participant location and demographics.

Note: Refer to Continuous Improvement Cultural Responsiveness Tools for original image.

Stage 1: Cultural Responsiveness Consultation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Stakeholders

Stage 1 included 30 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander individuals working in government, nongovernment and private practices who partook in either a yarning session or a survey. These stakeholders were sourced through three main strategies:

via social workers who had an established relationship with the researcher;

via professional networks such as Indigenous Allied Health Australia (IAHA) and the Australian Association of Social Workers (AASW);

via a cold-call email sent to over 30 Indigenous and non-Indigenous government and nongovernment organisations across Australia (for example, Human Services, Centrelink, NACHO, Aboriginal health organisations, and Lowitja Institute).

Stage 2: Culturally Responsive Practice Consultation with Social Workers, Stages 2 and 2a

The researcher and research assistant attended the AASW 2018 conference in Adelaide where they conducted 10 interviews and received 34 completed surveys. After this conference, the invitation to participate in the research was advertised on the AASW website. The stakeholders also distributed the invitation to participate in the research among their professional networks. From this, a further 72 social workers completed the survey and a further 14 social workers were interviewed, totalling 130 participants. Participants also indicated via the survey or an interview if they wished to participate in further stages of the research. After the initial surveys and interviews, a further five social workers were interviewed to provide a conversation about examples of cultural responsiveness, the aim of which was to arrive at examples of what successful, culturally appropriate practice might look like. Analysis of all interviews and the survey was undertaken via NVivo, SPSS, and thematic analysis was completed on an Excel spreadsheet.

Stage 3: Collaborative Development of Tools

After stages 1 and 2, we used the feedback from participants and the literature review to develop an audit tool that could be used by individuals, teams, and organisations, as well as a visual representation that could be printed out and a short survey that could measure cultural responsiveness with a booklet identifying further resources that would be useful for developing cultural responsiveness. As part of developing a sustainable and effective tool, the project used acceptability testing with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stakeholders and social workers in the field to ensure that the tools can be used in practice and are culturally appropriate and professionally applicable (Ayala & Elder, Citation2011; Barnett & Kendall, Citation2011). From here, stakeholders were given the draft documents to review language and cultural appropriateness and to provide general feedback. The tools were then finalised and developed visually with an Aboriginal graphic designer.

Stage 4: Piloting

A small group of social workers, both Aboriginal and non-Indigenous, piloted the tools for themselves and within their organisations. The social workers included in the pilot group were from government, nongovernment, and private practice organisations. The pilot group was diverse in gender, age and in other aspects, including being representatives from the LGBTIQ+, Muslim, and disability communities.

Stage 5: Dissemination

An online symposium to launch and discuss the tools is planned and will be hosted by the University of the Sunshine Coast with invited participants, scholars, and stakeholders to present on topics related to the measurement and evaluation tool and the applications for social work in the field. Results will be disseminated via social workers in the field, journal articles, and conference presentations. Furthermore, and importantly, the results will be shared with the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander services that were utilised as stakeholders. The tools will be housed online at the Indigenous and Transcultural Research Centre, University of the Sunshine Coast. Ethics for this project was approved by the University of the Sunshine Coast.

Findings

The 7 Ngurras

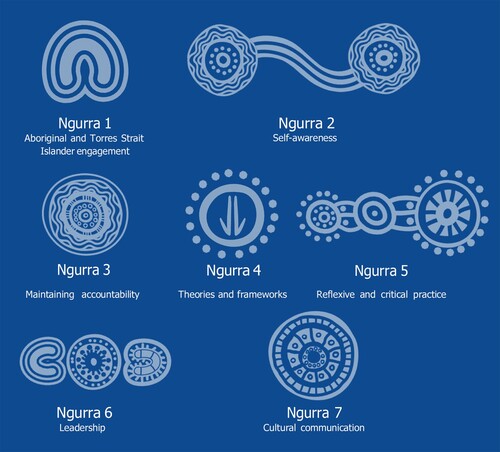

We must acknowledge that this work was achieved through the meaningful contributions, time, energy, and knowledge of many people capturing their perspectives, knowledge, values, and understandings of cultural responsiveness over the 3-year project. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community consultation process evolved over the three stages. The timeframe ensured maximum community participation and two-way consultation. It also guaranteed community members the ability to choose to what extent they wished to contribute to the process. An outcome of the community consultations was the development of seven key domains that were identified as pivotal in culturally responsive practice when working in Australia. The use of the word “Ngurras”, which means camps in many Aboriginal languages, was gifted to the researchers by a stakeholder. The word “camps” also signifies the differing countries existing in and across Australia. The Ngurras recognise that individual and organisational efforts to be culturally responsive are an ongoing journey. Actions across each of the 7 Ngurras are not linear and should be undertaken concurrently and with reference to each other (see ).

Figure 2. The Seven Ngurras.

Note: Refer to Continuous Improvement Cultural Responsiveness Tools for original image.

Ngurra 1: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Engagement

This Ngurra includes collaboration, reciprocity, mutual respect, consumer participation, trust through partnership, local cultural context, community empowerment, and capacity strengthening. Social workers will know they are being successful in this Ngurra if they have current and emerging partnerships with community groups, other organisations, and professional bodies to plan, deliver, and monitor effective models of services and partnerships that improve Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and wellbeing. They will be sharing information and developing networks that celebrate and actively participate in historical events of significance that recognise and promote culture (e.g., National Reconciliation Week, Mabo Day, NAIDOC Week, Coming of the Light, and National Sorry Day). Organisations will include Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stakeholders in decision making and policy direction, with continuous strategic analysis to monitor progress and modify practices when it is appropriate. Social workers will recognise and acknowledge the importance of engaging with the diversity and difference within and between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and maintain the principle of core responsibility to ensure the creation of a culturally responsive workplace.

Ngurra 2: Self-Awareness

Self-awareness refers to the continuous development of self-knowledge, including an understanding of personal beliefs, assumptions, open-mindedness, respect for diversity, values, perceptions, attitudes, and expectations, and how these impact relationships with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. For individuals, this involves being able to constantly challenge their assumptions, bias, and preconceived ideas either on their own, with peers, in supervision, or in training. It is critical that all social workers have a deep understanding of their own values, attitudes, worldviews and biases, along with a strong ability to acknowledge how these influenced their practice and impact on others, either positively or negatively. An organisation will identify both organisational and individual needs in developing and maintaining self-reflection for decisions and actions. They will support and create reflective practice models for decisions and actions.

Ngurra 3: Maintaining Accountability

This Ngurra includes the process of owning their role and monitoring progress in addressing inequalities between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples and other Australians including planning and service delivery, building evidence, policy and cultural procedures, monitoring and evaluation, professional development, and cultural training. Social workers will monitor goal achievement and engage with, and develop, their culturally responsive practice. In this way, they can begin to lead by example and model culturally responsive actions via yearly planning processes. Social workers will then advocate to include cultural responsiveness in policy and planning processes with set targets to monitor goals and achievements. Organisations will also include cultural responsiveness in policy and planning processes with set targets to monitor goals and achievements.

Ngurra 4: Theories and Frameworks

There are many key theories and frameworks identified to be key learnings to address racism and to create antioppressive practice including White privilege, critical race theory, intersectionality, White fragility, strengths approach, narrative therapy, Dadirri and yarning (Bessarab & Ng’andu, Citation2010; Crenshaw, Citation2017; Crenshaw et al., Citation1995; DiAngelo, Citation2018; Moreton-Robinson, Citation1998; Saleebey, Citation1996; Ungunmerr, Citation2017; White & Espton, Citation2004). A social worker would commit to undertaking regular training and refresher courses, seminars, forums, webinars, and online training opportunities around both skills and knowledges. They would develop and then implement an action plan for their professional practice with Specific, Measurable, Assignable, Realistic, and Time-related goals (SMART) (Bjerke & Renger, Citation2017). Social workers actively take opportunities to reflect on practice so that they can change practices and processes that are not culturally responsive, and this involves advocating to the organisation and to colleagues. Organisations can create, lead, and support discussions, training, and opportunities to further develop knowledge and skills around cultural responsiveness and antiracist practices.

Ngurra 5: Reflexive and Critical Practice

All social workers in Australia must be aware of, and have education on, the ongoing impact of colonisation including the government policies that created intergenerational trauma. Social workers must learn from this past and listen to the lived experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. A social worker should have a basic understanding of the real history of settlement in Australia and how it has impacted First Peoples. Furthermore, social workers should appreciate the role they can play in sharing this knowledge and building awareness of the need for recognition of these truths. This means they are advocating for their organisation to have an ongoing commitment to reconciliation, sovereignty, and governance for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. They will develop policies and programs that consider and respond to the cultural needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, broadly as the First Peoples of Australia and locally for the many different Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures.

Ngurra 6: Leadership

Leaders are committed to true consultation and empowerment; they aim for real social justice for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. Social workers lead a strength-based, nondeficit approach to practice. Individuals try to influence, improve, create change, and set cultural responsiveness targets and indicators for individuals and organisations. Organisations have joint leadership and governance structures involving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples making decisions about strategic matters, resource allocation, and negotiating in organisational mission and services. They ensure that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people feel involved, respected, and valued with choices of care. Policies and procedures are reviewed and refreshed based on feedback from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander staff, service users, and the community. Cultural responsiveness is championed throughout the organisation and acknowledges and promotes personal, colleague, and organisation successes including specific cultural ambassadors and mentoring.

Ngurra 7: Cultural Communication

Individuals ensure that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander service users have access to accredited interpreters and/or Aboriginal support or community liaison workers when this is necessary. Social workers working with local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and organisations support communication with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander consumers to provide more effective, quality care while improving access and pathways of care between organisations and mainstream services. Individuals will use cultural ways (e.g., yarning), technology (e.g., audio-visual and social media), and electronic tools to deliver information at the right time, in the right place, and in multiple formats and languages to meet needs.

Organisations will provide training for staff to develop their awareness of, and strengthen, their interpersonal communication techniques (including when working with interpreters) and improve the mutual sharing of information relevant to the service user’s needs. Social workers will develop culturally appropriate education sessions for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander service users (e.g., to improve health literacy), which will support service users to make informed decisions. They will ensure appropriate signage, commonly used forms, education, and audio-visual materials are appropriate for the needs of local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Organisations will develop culturally safe and responsive environments (e.g., specific literature, artworks, flags, posters, and decor) that are designed with consideration for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander consumers.

Discussion

The underlying goal of the Continuous Improvement Cultural Responsiveness Tools (CICRT) was to create an evolving, living document that exists as a valuable reference point for all social workers to utilise to continue to improve their cultural responsiveness. The tools aim to:

support social workers, human services, and community workers to self-assess their transformation towards cultural safety for their capacity-development purposes;

provide a means to demonstrate stakeholders’ voices around cultural responsiveness;

create culturally improved responsiveness practice for social workers within Australia

assist in identifying knowledge and skill gaps;

provide consistency of approach across the social work profession;

support the AASW in its commitment to the process of reconciliation with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples;

improve services and thus the wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples.

Continuous Improvement Cultural Responsiveness Tools (CICRT)

The group of tools known as the CICRT incorporates a pragmatic, strengths-based, four-factored, integrated approach to help support social workers and their respective organisations develop their cultural responsiveness and preparedness when working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities (see ).

Tool 1: The Booklet

The booklet provides a clear working definition of cultural responsiveness, why it is imperative to social work, and provides an in-depth description of the 7 Ngurras, which were developed in collaboration and consultation with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stakeholders. The general and specific resource sections aligned to the 7 Ngurras provide individuals with clear steps outlining where significant literature and useful resources can be accessed to enhance the reader's level of cultural responsiveness and understanding.

Tool 2: The Audit Tool

The audit tool provides a continuum of cultural responsiveness understanding ranging from “unaware” to “continuing”. The audit tool provides a broad range of questions that are captured under relevant subheadings. Individuals and organisations engaging with the tool will receive a tallied score which equates to a final location that is situated along the continuum. This represents their current level of cultural responsiveness. This tool is perfect for self-reflection, peer review, and general conversations with your social work supervisor.

Tool 3: Critical Reflexive Section

This section encompasses a reflective cycle, self-reflective worksheet, and a visual model. These materials can be used to help guide social workers to transition through concepts of critical reflection and reflexivity. The reflective spaces are linked to the 7 Ngurras, to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ways of knowing, being, and doing (Martin & Mirraboopa, Citation2003), and to the AASW core values (AASW, Citation2010).

Tool 4: Survey

The survey is divided up into two sections: a values section and an actions section. Together, the sections provide participants with a series of detailed questions probing their thoughts and outlining their respective actions in respect to supporting, enhancing, and delivering culturally responsive social work practice. After the survey, participants will be provided with a baseline assessment of their culturally responsive values and an identification of their current level of action or inaction in respect to cultural responsiveness practices. From both scores, participants will be able to identify areas that require further development, and the survey will provide participants with enough information to support an action plan or inform professional supervision plans. Participants may wish to share their scores and process learning with their professional peers for transparency and accountability, and to discuss team responsiveness collaboratively. Positive cultural responsiveness results may be used to showcase organisations or teams progress internally or externally. This survey will provide sufficient, robust evidence necessary to demonstrate cultural responsiveness in practice and to identify any strategies and priority areas for future improvement. It is noted that not all the listed actions or attributes from the combined tools will be relevant to every individual or organisation. Therefore, we would expect that not all boxes under any one subheading will be covered. Also, individuals or organisations may have developed other, more locally relevant actions and attributes that can be described and evidenced in social work practice.

The Four Tools

These tools aim to assist in the development of the successful implementation of a whole-of-organisation response to culturally responsive practice. It can be integrated into agency and capability frameworks and used in conjunction with existing frameworks for leadership, core skills, and management expertise. If appropriate, other suggestions for using these tools include:

ongoing consultation with service users, staff, communities, and other key stakeholders

reviews of organisational practice and action to modify practice when required

an individual and organisational evaluation of outcomes.

These tools could be used in conjunction with your organisation’s Aboriginal Employment Strategy and Reconciliation Action Plan, or equivalent policies, and personal and organisational learning plans. These tools utilise almost universally accepted core principles for effective Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and community service delivery and justice delivery. These tools have been developed to encourage social workers to engage in critical reflection and assess individual current skills, knowledge, and experience of cultural responsiveness. The results from completing the assessment for the first time provide a valid and reliable baseline indication of the social worker’s (or, collectively, the organisation’s) level of cultural responsiveness. These tools can be used in conjunction with any existing tools and can be aligned to timeline and outcome-oriented goals.

Conclusion

This project actively sought to engage key stakeholders (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and social workers) to create more culturally responsive social workers. This opportunity to promote stronger responsive relationships between social workers and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people will ultimately result in culturally relevant best practices that will assist in developing higher levels of social, emotional, and physical wellbeing for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities. The hope for the CICRT is that it will assist Australian social workers in moving from immobilisation, fear, and ignorance to instead feel supported to develop culturally responsive skills that are reflective, action-oriented, measurable, and able to be evaluated in the future.

Acknowledgements

The authors of this paper woudl like to acknowledge that this paper was written on the unceded soverign lands of the Jinibara and Gubbi Gubbi/Kabi Kabi peoples. Bindi is a Gamilaraay woman and Claire is a non-Indigenous settler. We pay genuine respect to Elders past and present.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Australian Association of Social Workers (AASW). (2010). Code of ethics. Canberra. https://www.aasw.asn.au/document/item/1201

- Australian Association of Social Workers (AASW). (2012). Guideline 1.1: Guidance on essential core curriculum content. Australian Social Work Education and Accreditation Standards (ASWEAS). https://www.aasw.asn.au/document/item/3552

- Australian Association of Social Workers (AASW). (2013). Practice standards. Canberra. https://www.aasw.asn.au/document/item/4551

- Australian Association of Social Workers (AASW). (2015). Australian social work education and accreditation standards.

- Australian Association of Social Workers (AASW). (2016). Preparing for culturally responsive and inclusive social work practice in Australia: Working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Canberra. https://www.aasw.asn.au/document/item/7006

- Ayala, G., & Elder, J. (2011). Qualitative methods to ensure acceptability of behavioural and social interventions to the target population: Qualitative methods in acceptability research. Journal of Public Health Dentistry, 71, S69–S79. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-7325.2011.00241.x

- Barnett, L., & Kendall, E. (2011). Culturally appropriate methods for enhancing the participation of Aboriginal Australians in health-promoting programs. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 22(1), 27–32. https://doi.org/10.1071/HE11027

- Bennett, B. (2003). Hearing the stories of Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social workers: Challenging and educating the system. Australian Social Work, 56(1), 61–70. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0312-407X.2003.00054.x

- Bennett, B. (2013). The importance of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander history for social work students and graduates. In B. Bennett, S. Green, S. Gilbert, & D. Bessarab (Eds.), Our voices: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social work (pp. 1–26). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bennett, B. (2015). “Stop deploying your white privilege on me!” Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander engagement with the Australian Association of Social Workers. Australian Social Work, 68(1), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2013.840325

- Bennett, B. (2019). The importance of Aboriginal history for practitioners. In B. Bennett, & S. Green (Eds.), Our voices: Aboriginal social work (2nd ed., pp. 3–30). Red Globe Press.

- Bennett, B., Redfern, H., & Zubrzycki, J. (2018). Cultural responsiveness in action: Co-constructing social work curriculum resources with aboriginal communities. The British Journal of Social Work, 48(3), 808–825. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcx053

- Bennett, B., Zubrzycki, J., & Bacon, V. (2011). What do we know? The experiences of social workers working alongside Aboriginal people. Australian Social Work, 64(1), 20–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2010.511677

- Bessarab, D., & Ng’andu, B. (2010). Yarning about yarning as a legitimate method in Indigenous research. International Journal of Critical Indigenous Studies, 3(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcis.v3i1.57

- Bjerke, M., & Renger, R. (2017). Being smart about writing SMART objectives. Evaluation and Program Planning, 61, 125–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2016.12.009. Burgess, 2004.

- Centre for Cultural Competence Australia. (2021, February). Centre for Cultural Competence Australia. https://www.ccca.com.au/content/home.

- Cranney, M., & Indigenous Allied Health Australia. (2015). Cultural responsiveness in action: An IAHA framework. Indigenous Allied Health Australia.

- Crenshaw, K., Gotanda, N., Peller, G., & Thomas, K. (1995). Critical race theory. The key writings that formed the movement. New York.

- Crenshaw, K. W. (2017). On intersectionality: Essential writings. The New Press.

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. SAGE.

- Daniel, C. L. (2008). From liberal pluralism to critical multiculturalism: The need for a paradigm shift in multicultural education for social work practice in the United States. Journal of Progressive Human Services, 19(1), 19–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/10428230802070215

- DiAngelo, R. (2018). White fragility: Why it's so hard for white people to talk about racism. Beacon Press.

- Dominelli, L. (2018). Anti-racist social work (4th ed). London: Palgrave. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-53420-0

- Dudgeon, P., Milroy, H., & Walker, R. (2014). Working together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and wellbeing principles and practice (2nd ed.). Kulunga Research Network.

- Feilzer, M. (2010). Doing mixed methods research pragmatically: Implications for the rediscovery of pragmatism as a research paradigm. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. Online First. October 22, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689809349691

- Green, S., Bennett, B., & Betteridge, S. (2016). Cultural responsiveness and social work – a discussion. Social Alternatives, 35(4), 66–72. https://doi.org/10.3316/ielapa.872319626183827

- Hertel, A. (2017). Applying Indigenous knowledge to innovations in social work education. Research on Social Work Practice. 27(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731516662529

- Laird, S. (2008). Anti-oppressive social work: A guide for developing cultural competence. Sage.

- Lee, J. (2013). Indigenous voices in social work. AASW National Bulletin Spring. https://www.aasw.asn.au/document/item/4904.

- Mackinlay, E., & Barney, K. (2014). Unknown and unknowing possibilities: Transformative learning, social justice, and decolonising pedagogy in Indigenous Australian studies. Journal of Transformative Education, 12(1), 54–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344614541170

- Mafile’o, T., & Vakalahi, H. F. O. (2018). Indigenous social work across borders: Expanding social work in the South Pacific. International Social Work, 61(4), 537–552. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872816641750

- Martin, K., & Mirraboopa, B. (2003). Ways of knowing, being and doing: A theoretical framework and methods for Indigenous and Indigenist re-search. Journal of Australian Studies, 27(76), 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/14443050309387838

- Moreton-Robinson, A. (2014). Subduing power: Indigenous sovereignty matters. In T. Neale, E. Vincent, & C. McKinnon (Eds.), History, power, text: Cultural studies and Indigenous studies [CSR Books, Number 2] (pp. 189–197). UTS ePRESS.

- Moreton-Robinson, A. M. (1998). White race privilege: Nullifying native title. Bringing Australia together: The structure and experience of racism in Australia. In Bringing Australia together: The structure and experience of racism in Australia (pp. 30–44). FAIRA, Foundation for Aboriginal and Islander Research.

- Muller, L. (2014). A theory for Indigenous Australian health and human service workers: Connecting Indigenous knowledge and practice. Routledge.

- Nakata, M. (2007). Disciplining the savages: Savaging the disciplines. Aboriginal Studies Press.

- Parker, R., & Milroy, H. (2014). Mental illness in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. In P. Dudgeon, H. Milroy, & R. Walker (Eds.), Working together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and wellbeing principles and practice (2nd ed, pp. 113–121). Australian Government Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. https://www.telethonkids.org.au/globalassets/media/documents/Aboriginal-health/working-together-second-edition/wt-part-2-chapt-7-final.pdfRigney, 1999.

- Rigney, L. I. (1999). Internationalization of an Indigenous anticolonial cultural critique of research methodologies: A guide to Indigenist research methodology and its principles. Wicazo Sa Review, 14(2), 109–121. https://doi.org/10.2307/1409555

- Rorty, R. (1999). Philosophy and social hope. Penguin Books.

- Saleebey, D. (1996). The strengths perspective in social work practice: Extensions and cautions. Social Work, 41(3), 296–305. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/41.3.296

- Stewart, S. (2006). Cultural competence in health care. Diversity Health Institute – Position paper, Sydney, http://www.dhi.gov.au/wdet/pdf/Cultural%20competence.pdf.

- Taylor, K. P., Bessarab, D., Hunter, L., & Thompson, S. C. (2013). Aboriginal-mainstream partnerships: Exploring the challenges and enhancers of a collaborative service arrangement for aboriginal clients with substance use issues. BMC Health Services Research, 13(1), https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-12

- Teddlie, C., & Tashakkori, A. (2009). Foundations of mixed methods research: Integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches in the social and behavioral sciences. Sage.

- Ungunmerr, M. R. (2017). To be listened to in her teaching: Dadirri: Inner deep listening and quiet still awareness. EarthSong Journal: Perspectives in Ecology, Spirituality, and Education, 3(4), 14–15.

- Walter, M., & Andersen, C. (2013). Indigenous statistics: A quantitative research methodology. Left Coast Press.

- White, M., & Epston, D. (2004). Externalizing the problem. In C. Malone, L. Forbat, M. Robb, & J. Seden (Eds.), Relating experience: Stories from health and social care (pp. 88–94). Routledge.

- Wilson, D. (2008). Should non-Maori research and write about Maori? There is a role for non-Maori nurse researchers, as long as they respect and observe Maori processes, and work collaboratively with the appropriate people. Nursing New Zealand (Wellington, N.Z.: 1995), 14(5), 20.

- Zubrzycki, J., Green, S., Jones, V., Stratton, K., Young, S., & Bessarab, D. (2014). Getting it right: Creating partnerships for change. Integrating Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledges in social work education and practice. Teaching and Learning Framework. Australian Government Office for Learning and Teaching, Sydney.