ABSTRACT

While Aboriginal youth mentoring has been used as a teaching process for thousands of years and the tradition continues, little attention has been paid to documenting what elements make learning experiences transformational. As part of the evaluation of the Aldara Yenara mentoring program, this Aboriginal-led scoping review examined literature about transformational mentoring programs from Canada, Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand to understand their key elements and provide guidance for future research and practice. The use of relational mapping was applied in an attempt to locate literature written by Aboriginal scholars including grey literature. Twenty-seven documents were reviewed including 20 from the peer-reviewed literature and seven acquired through the relational mapping. A total of 13 met the inclusion criteria, predominantly written by non-Aboriginal authors. Four distinct themes emerged and informed our narrative synthesis. Absent in this material, largely neither led nor owned by Aboriginal people, was any reference to connection to Country as central to Aboriginal transformational healing programs. Without Aboriginal leadership, communication and processes in these programs, there was a failure to draw on Aboriginal understandings of healing spaces. From here on in, research and practice in this area must be Aboriginal-led to ensure deeper, Aboriginal-informed understandings for First Nations transformational mentoring programs.

IMPLICATIONS

Existing youth mentoring literature is dominated by western understandings and perceptions. Thus, it often fails to offer the nuanced benefits of Aboriginal youth holding or growing their relationship to Country for their wellbeing and personal development

Mentoring programs that are culturally strong from First Nations worldviews are key to providing transformational experiences: that is, cultural connectedness encourages, motivates, and creates healing spaces for Aboriginal youth

While social work has facilitated normative western narratives for youth and their wellbeing, future Aboriginal mentoring program need to be both led and evaluated by First Nations people.

Positioning of the Study

By acknowledging Yorta Yorta Country, the authors pay tribute and show respect to First Nations Peoples, recognising their enduring relationship to Country. This article was written on unceded land. The word Aboriginal reflects a broader international perspective of various Indigenous communities across Australia, Aotearoa New Zealand, and Canada, including First Nations, Inuit, Métis, Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, as well as Māori and Pasifika communities. Aboriginal is used as an overarching term and can refer to any of the above communities.

To address relational accountability (Steinhauer, Citation2002), the authors are introduced. Dr McMahon, Mr Chisholm, staff at Aldara Yenara, and Ms Garling are proud Aboriginal peoples. The last three authors are non-Indigenous. The first and last author are social work scholars and critical of social work practice and research that centres western narratives about Aboriginal youth wellbeing.

The scoping review of the literature presented here is part of the Aldara Yenara youth mentoring program evaluation. The program aims to facilitate culturally appropriate healing through traditional men’s and women’s business and mentoring sessions with Elders (Aldara Yenara, Citation2022). We acknowledge that in current mentoring practice and policy statements, Aboriginal LGBTIQA + young people are not seen, heard, or accounted for (Bennett & Gates, Citation2019).

Mentoring and Aboriginal Wellbeing

Mentoring is a structured and trusting relationship that brings young people together with caring individuals who offer guidance, support and encouragement (Youth Affairs Council Victoria, Citation2022). This definition aligns with Aboriginal tradition and beliefs (Klinck et al., Citation2005). We acknowledge that in the collective mentoring environment, one-on-one mentoring occurs. This can be signified when a young person begins calling a particular older person Aunty or Uncle. Group mentoring aims to create safe spaces that enable a sense of belonging, supporting young Aboriginal people to explore their culture and identity (Fast, Citation2014). Sense of identity and history have been shown to be crucial factors in supporting resilience and wellbeing in Indigenous youth (Wexler, Citation2009). This sense of identity relates to a positive relationship between self and culture and may serve as a protective factor against negative health outcomes exacerbated by racism (Fast, Citation2014). Aboriginal youth who are disconnected from their community or culture may be looking for ways to reconnect, and Aboriginal mentoring programs support such connections (Carriere, Citation2015; Fast, Citation2014).

Wellbeing within Aboriginal worldviews encompasses the physical, emotional, social, and cultural wellbeing of both the individual and the whole community. This is strongly tied to Aboriginal peoples’ connection to Country and culture (Yap & Yu, Citation2016). First Nations worldviews, or ontology, are relational, requiring deep listening to local communities, Country and Ancestors (O’Chin, Citation2020). A central tenet of relational worldviews is that all entities, including animals, the elements, Country, seasons, humans, the spirit world, Ancestors and waterways, are in a web-like, interdependent relationship (McMahon, Citation2017). Consequently, an individual’s sense of belonging to the whole lifeworld is a key element within Aboriginal worldviews (McMahon, Citation2017; Townsend & McMahon, Citation2021). Cultural connectedness can be defined as the knowledge of, and engagement with, belonging to aspects of Aboriginal culture, as well as philosophical ways of knowing, being and doing (Snowshoe et al., Citation2017). Cultural connectedness is associated with mental health, wellness and healing for Aboriginal youth.

Occurrence of group mentoring for Aboriginal youth is evident, frequently as a means to empower and engage Aboriginal young people to be strong, healthy and proud (Crooks et al., Citation2017; Ferguson et al., Citation2021; Hirsch et al., Citation2016). However, little is known regarding what elements of mentoring create a transformational mentoring experience for Aboriginal young people. The word transformational includes a combination of positive changes related to identity, belonging, wellbeing and cultural connection (Crooks et al., Citation2017; Fast, Citation2014; Wexler, Citation2009). This scoping review aimed to both develop an understanding of what elements create a transformational mentoring experience as well as offer guidance for future research and practice led and informed by First Nations perspectives for collective transformational healing.

Methods

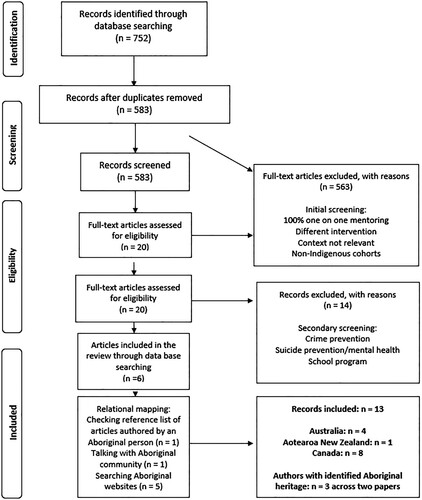

The overarching question driving this research was: What is needed to create transformational mentoring experiences for Aboriginal young people? CINAHL, PsycINFO, ProQuest Central and Informit databases were searched for publications from 2011 to 2021 (). To ensure that relevant evidence was retrieved, search terms were developed using a modified version of the PICOFootnote1 method with the support of a (Non-Indigenous) librarian (Richardson et al., Citation1995). The scope of the search was limited to (i) Aboriginal young people between 8–18 years, and (ii) group mentoring. Only articles in English were included. As well, articles focused specifically on crime prevention, school programs, suicide and mental health, or only addressed one-on-one mentoring were excluded to align with youth that are part of the Aldara Yenara group mentoring program. Box 1 displays inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Box 1 Inclusion/exclusion criteria

We acknowledge that this approach aligns with western research methods (Martin & Mirraboopa, Citation2003), as Aboriginal-authored texts may not necessarily be found through library data searches or in high-impact journals. To locate literature written by Aboriginal scholars, relational mapping was applied (McMahon, Citation2021; Rigney, Citation2001). This involved checking the reference list of an article authored by an Aboriginal person to learn about other key articles, talking to Aboriginal community members, and searching for articles on websites to identify Aboriginal organisation resources. Using relational mapping in addition to the conventional scoping review enabled our examination to be inclusive of all contemporary academic discourses, not just dominant western ways of knowing. This method enabled the focus to be placed on locating Aboriginal texts in the field of Aboriginal youth mentoring, overcoming historical systems of gatekeeping in academic journals (McMahon, Citation2021). Completing relational mapping within the methodology of a literature review is added to academic rigour. Regardless of whether the researcher is Aboriginal or non-Aboriginal, a review needs to be inclusive of all contemporary academic discourses, so results are not simply reiterating dominant ways of knowing.

An important step in the process was to modify Arksey and O’Malley’s (Citation2005) framework for scoping reviews to include Aboriginal relational mapping (McMahon, Citation2021; Rigney, Citation2001); identifying the research question, identifying relevant studies, relational mapping, study selection, charting the data, collating, summarising and reporting results. JV and CM screened the titles, abstract and content against the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Box 1). MM checked the results and compared the findings with CM. MM undertook relational mapping. For full-text screening, 20 articles were retrieved, which were screened by two reviewers independently (MM and CM), only six met the inclusion criteria. A further seven articles were identified through a grey literature search and relational mapping (CM and JV). Discrepancies were discussed and resolved by consensus between CM, MM and JV. A total of 13 studies met all inclusion criteria and were included in the review. CM and JV discussed initial themes that were reviewed with MM and then further refined into four overarching themes. During this process, findings were shared and discussed with all authors involved. A narrative synthesis was chosen as a method suited to the appraisal of included studies, utilising an iterative and conceptual approach that emphasises western and Aboriginal ways of doing to develop a critique based on credibility and contribution to evidence (Davies, Citation2019; McMahon, Citation2021).

Results

This scoping review provides an overview of the studies undertaken in Australia (n = 4), Canada (n = 8) and New Zealand (n = 1) that are relevant for group mentoring with First Nations young people. Of the 13 articles identified, 12 reported empirical data and one presented an exploratory report. Only two articles had authors with identified Aboriginal heritage. The studies used a range of methodologies, but the majority used a qualitative methodology (n = 7). The programs presented in these studies had durations from several days to two years. Seven studies included the voices of Aboriginal young people.

Four distinct, but intertwined themes relevant to the experiences of mentoring for young Aboriginal people emerged from this scoping review: (i) Programs need to be culturally embedded in a First Nations standpoint; this impacts on; (ii) the development of intrapersonal skills and (iii) interpersonal relationships and (iv) program design. Important note, language used to describe results was informed by the literature, we did not attempt to Indigenise the wording or meanings.

Culturally Embedded in a First Nations Standpoint

Most of the mentoring programs had a strong focus on culture, which included activities such as community circles (Crooks et al., Citation2017), storytelling (Crooks et al., Citation2017), cultural ceremonies (Kope & Arellano, Citation2016), cultural teachings (Ferguson et al., Citation2021) or games (Lopresti et al., Citation2021). These activities encouraged the celebration of local culture and traditional teachings (Kope & Arellano, Citation2016). Community engagement through these activities was seen as a positive attribute in multiple studies (Crooks et al., Citation2017; Ferguson et al., Citation2021; Kope & Arellano, Citation2016; Lopresti et al., Citation2021; Peralta et al., Citation2018), as it allowed young persons to take responsibility in cultural ceremonies (Hirsch et al., Citation2016) and collaborate with other youth and community leaders (Kope & Arellano, Citation2016; Lopresti et al., Citation2021). This sparked a desire for further learning and acknowledgment of the importance of local culture and spiritual teachings (Ferguson et al., Citation2021; Kope & Arellano, Citation2016). The cultural activities allowed young people to partake in the decision-making process (Hirsch et al., Citation2016), included a range of cultural teachings (Ferguson et al., Citation2021) and were meaningful, such as maintaining community swimming pools (Ware, Citation2013), harvesting activities (Pizzirani et al., Citation2019), providing food to the local community and ceremonies (Hirsch et al., Citation2016). These types of activities helped build a stronger sense of belonging for Aboriginal young people and provided an opportunity for reciprocity, which is important in Aboriginal cultures (Kope & Arellano, Citation2016; Ware, Citation2013).

Culture also was mentioned as an enabler to create an environment of trust and equality. This allowed young people to connect cultural teachings to their current life experiences within a safe space (Crooks et al., Citation2017). Creating this environment of trust was done through community circles and storytelling (Crooks et al., Citation2017; Ferguson et al., Citation2021). Through this cultural connectedness, highlighting the extent to which individuals are embedded in their cultural group and their connection to the community, Country and Ancestors, young people were able to build both individual and collective resilience (Crooks et al., Citation2017; Hirsch et al., Citation2016). Aboriginal youth were able to embrace their individuality and explore their cultural identity, which had a positive effect on their wellbeing and intrapersonal growth (Crooks et al., Citation2017). Cultural connectedness encouraged both shared responsibility for learning and an appreciation of local Ancestry (Ferguson et al., Citation2021; Hirsch et al., Citation2016; Kope & Arellano, Citation2016; Pizzirani et al., Citation2019).

Integration of culture in the programs was seen as an ongoing process (Arellano et al., Citation2018). This should be at the discretion of, and in collaboration with, local Aboriginal communities (Arellano et al., Citation2018). Cultural training of non-Aboriginal staff was seen as crucial, but multiple studies reported that this was insufficient (Arellano et al., Citation2018; Crooks et al., Citation2017; Peralta et al., Citation2018). Most programs included Aboriginal collaboration related to program delivery, whether this was through Elders’ involvement, Aboriginal mentors or local Aboriginal community involvement (Arellano et al., Citation2018; Crooks et al., Citation2017; Ferguson et al., Citation2021; Halsall & Forneris, Citation2018; Hirsch et al., Citation2016; Kope & Arellano, Citation2016; Lopresti et al., Citation2021; Peralta et al., Citation2018; Pizzirani et al., Citation2019; Richards et al., Citation2011). Most studies were unclear or did not mention if a program was designed in collaboration with a local Aboriginal community, nor if Aboriginal community members were involved in regular meetings to evaluate or give feedback on the program (Ferguson et al., Citation2021; Halsall & Forneris, Citation2018; Kope & Arellano, Citation2016; Lopresti et al., Citation2021; Peralta et al., Citation2018; Richards et al., Citation2011).

Only two articles had authors with Aboriginal heritage involved in every step of the study, including protocol design, data collection and analysis (Farruggia et al., Citation2011; Hirsch et al., Citation2016). Whilst a few studies mentioned approval of their protocol (Crooks et al., Citation2017; Kope & Arellano, Citation2016), others simply stated that it was a collaborative study with an Aboriginal-controlled organisation (Peralta et al., Citation2018) or got feedback from community members (Crooks et al., Citation2017; Halsall & Forneris, Citation2018). Most studies did not report active Aboriginal collaboration in the evaluation or analysis (Arellano et al., Citation2018; Crooks et al., Citation2017; Farruggia et al., Citation2011; Halsall & Forneris, Citation2018; Kope & Arellano, Citation2016; Lopresti et al., Citation2021; Pizzirani et al., Citation2019; Richards et al., Citation2011; Ware, Citation2013).

Intrapersonal Skills

Intrapersonal skills focus on self-awareness and individual internal attitudes and processes (Sawatsky et al., Citation2016). These skills may include individual growth (Crooks et al., Citation2017), critical reflection (Hirsch et al., Citation2016) and individual resilience (Hirsch et al., Citation2016). The positive effect of group mentoring ranged from practical everyday skills, such as public speaking (Halsall & Forneris, Citation2018), to a sense of belonging and cultural identity (Ferguson et al., Citation2021; Pizzirani et al., Citation2019). Programs were reported to have a positive impact on self-confidence, growth and overall comfort in group settings (Crooks et al., Citation2017). The mentors and facilitators were seen as role models in this process (Ferguson et al., Citation2021), demonstrating to be proud of being Aboriginal (Crooks et al., Citation2017). Skill-based activities allowed young people to develop attributes that they were able to apply to their life experiences, such as coping, conflict skills (Crooks et al., Citation2017), planning and supervising event skills (Halsall & Forneris, Citation2018), new ways to stay active (Ferguson et al., Citation2021), decision making and critical reflection skills (Hirsch et al., Citation2016).

Critical reflection and its application to personal life can facilitate important conversations. However, it was noted that this should be explored carefully as it has the potential to bring up traumatic experiences that mentors might not be equipped to deal with. Involving social workers and offering support from Elders and the community were suggested as potential solutions (Hirsch et al., Citation2016).

A few programs allowed young people to be involved in the decision-making process of events, offering them more responsibility or leadership roles as they gained experience within the program (Halsall & Forneris, Citation2018; Kope & Arellano, Citation2016). This encouraged the participants to develop strong leadership skills, but also increased their awareness of socio-political processes and provided a deeper understanding of community issues through direct connections (Hirsch et al., Citation2016). The mentoring experience helped in constructing a positive self-image, allowing young people to connect with their own identity while engaging with others in a safe environment (Ferguson et al., Citation2021).

These positive effects on intrapersonal skills had a consequent impact on young people’s lives and their community, with several studies reporting increased school attendance and achievement (Halsall & Forneris, Citation2018; Lopresti et al., Citation2021; Richards et al., Citation2011; Ware, Citation2013), reduced anti-social behaviour (Halsall & Forneris, Citation2018; Peralta et al., Citation2018; Richards et al., Citation2011; Ware, Citation2013) and increased positive interactions with their peers, family and community (Crooks et al., Citation2017; Ferguson et al., Citation2021; Hirsch et al., Citation2016; Ware, Citation2013). Mentoring sessions also encouraged strong inter-community relationships (Arellano et al., Citation2018; Halsall & Forneris, Citation2018), with mentors experiencing a sense of pride in contributing to a positive experience for others (Ferguson et al., Citation2021).

Interpersonal Skills

Interpersonal skills include the relationships between peers, mentors, and community. This involves collaboration, leadership, influence, and interaction (Sawatsky et al., Citation2016). Most programs included activities that promoted interpersonal relationships between the participants (Crooks et al., Citation2017; Ferguson et al., Citation2021; Halsall & Forneris, Citation2018; Hirsch et al., Citation2016; Lopresti et al., Citation2021; Peralta et al., Citation2018; Pizzirani et al., Citation2019). Young people learned positive communication and relationship skills, as well as how to apply these in real-life situations, such as when confronted with racism (Crooks et al., Citation2017). This helped strengthen peer relationships, which in turn built individual confidence (Crooks et al., Citation2017). It also allowed youth to develop positive new social connections and develop a group identity (Ferguson et al., Citation2021; Halsall & Forneris, Citation2018). In turn, this group identity engendered a sense of belonging, which encouraged engagement and potential for young people to explore leadership opportunities (Hirsch et al., Citation2016; Kope & Arellano, Citation2016). In some studies, physical activity was seen as a good way to develop these peer relationships (Lopresti et al., Citation2021; Peralta et al., Citation2018). These relationships were built through mutual respect, and this respect itself was seen as a catalyst for further positive changes (Pizzirani et al., Citation2019).

The relationships between young people and mentors emerged as a powerful outcome of mentoring programs. Mentors were seen as role models, but moreover, they were approachable, trustworthy, and relatable (Crooks et al., Citation2017). This allowed young people to identify a different relationship with their mentors compared to teachers (Crooks et al., Citation2017). Mentoring activities helped to build a mutual sense of trust (Ferguson et al., Citation2021; Halsall & Forneris, Citation2018), which created a sense of belonging for the young people involved (Ferguson et al., Citation2021). This helped them to recognise their value as part of the group, building social confidence (Halsall & Forneris, Citation2018). Activities through which this relationship was strengthened included sharing circles to debrief (Lopresti et al., Citation2021), physical activity (Peralta et al., Citation2018) and conversations in relation to culture (Crooks et al., Citation2017). Other important qualities of this relationship were a non-judgmental, fun, humorous, affirming, empowering, and inspiring attitude, which was built fundamentally upon trust (Ferguson et al., Citation2021; Peralta et al., Citation2018; Ware, Citation2013). The support from the mentors had a flow-on effect, which resulted in young people taking responsibility for, and contributing to, the wellbeing of others (Ferguson et al., Citation2021; Halsall & Forneris, Citation2018). It was important to build this relationship over a longer timeframe, with relationships of less than six months viewed as a potential disadvantage (Ware, Citation2013).

Building a relationship with the local Aboriginal community was also a strong contributor to a positive mentoring experience (Ferguson et al., Citation2021). Guest instructors or visitors from the community fostered this connection, with these community connections making young people feel safer (Ferguson et al., Citation2021). The programs created opportunities for larger community events, which increased a sense of community among young people (Halsall & Forneris, Citation2018). Undertaking specific activities with community members, such as harvesting, allowed young persons to build this connection and for the community to build collective resilience (Hirsch et al., Citation2016). Another program allowed youth to take on responsibility in socio-political processes, which fostered relationships with the Chief and Elders (Kope & Arellano, Citation2016). These intergenerational relationships enabled steps to be taken towards community-level empowerment.

Three studies defined a relationship with Country, including bush and land activities, as an important foundation for building strong individuals (Hirsch et al., Citation2016; Kope & Arellano, Citation2016; Ware, Citation2013). One program included a range of land-based activities, with harvesters taking the youth out on the land to teach them how to hunt, fish, collect firewood, navigate and prepare country foods (Hirsch et al., Citation2016). This connection to Country, built through an Aboriginal mentor (the harvester), enhanced both individual and collective resilience (Hirsch et al., Citation2016). A fourth study recommended that the program included more and longer bush activities to promote further positive outcomes (Peralta et al., Citation2018).

Program Design

Designing programs that are flexible and that offer the ability to evolve and change emerged as an important strength in mentoring programs (Arellano et al., Citation2018). Flexibility allowed the community to take ownership of the program and foster youth empowerment (Arellano et al., Citation2018). Regular meetings with staff, mentors, youth, parents and the community enabled improved programs (Hirsch et al., Citation2016). The quality and devotion of staff were seen as strengths (Arellano et al., Citation2018), but more Aboriginal staff and further education and training for non-Aboriginal staff were required (Arellano et al., Citation2018; Crooks et al., Citation2017; Peralta et al., Citation2018). Effective recruitment and screening, as well as ongoing training and support for the mentors, were important (Ware, Citation2013).

It was evident across most programs that longer mentoring periods had significantly better outcomes compared to shorter mentoring programs (Crooks et al., Citation2017; Halsall & Forneris, Citation2018; Peralta et al., Citation2018; Pizzirani et al., Citation2019; Ware, Citation2013). The longer duration allowed young people more time to open up (Arellano et al., Citation2018), take on responsibility (Halsall & Forneris, Citation2018), and gain more decision-making power (Kope & Arellano, Citation2016), each of which had a positive impact on the youth’s experience.

Gender was mentioned as an element to be considered by multiple programs (Crooks et al., Citation2017; Ferguson et al., Citation2021; Lopresti et al., Citation2021; Pizzirani et al., Citation2019). One program reported different impact on female and male young people through the program (Crooks et al., Citation2017). Another study mentioned a lack of male representation among the mentors (Ferguson et al., Citation2021), with male young people more likely to engage in activities with male youth facilitators (Lopresti et al., Citation2021). One program specifically mentioned having a boys’ and a girls’ camp but did not identify specific outcomes as a result of having gender-separated groups (Pizzirani et al., Citation2019).

Most programs had Aboriginal involvement in the program delivery, which could be through Elders (Arellano et al., Citation2018; Lopresti et al., Citation2021; Richards et al., Citation2011), mentors of Aboriginal heritage (Ferguson et al., Citation2021; Halsall & Forneris, Citation2018) or the program being run by a local community organisation (Kope & Arellano, Citation2016; Peralta et al., Citation2018; Pizzirani et al., Citation2019). Nearly half of the studies mentioned Aboriginal collaboration in either the design of the program or in continual feedback regarding its development (Arellano et al., Citation2018; Crooks et al., Citation2017; Ferguson et al., Citation2021; Halsall & Forneris, Citation2018; Hirsch et al., Citation2016; Lopresti et al., Citation2021; Pizzirani et al., Citation2019; Richards et al., Citation2011; Ritchie et al., Citation2014). However, it was not always clear how much a local Aboriginal community was involved, nor how shared decision-making was applied in the design of the program.

The location of the camp could have an impact on program design and the experience of the youth, specifically concerning the connectedness to Country. Six of the programs were held on Country (Hirsch et al., Citation2016; Kope & Arellano, Citation2016; Lopresti et al., Citation2021; Peralta et al., Citation2018; Richards et al., Citation2011; Ritchie et al., Citation2014), whereas the other seven were held either at various locations or were unclear about the role of the location in terms of program design, connection to Country and experience.

Discussion

This review explored what is needed to create transformational mentoring experiences for Aboriginal young people. We found significant gaps; first, the studies reviewed were predominantly not First Nations-led at all stages of the research; second, this inhibits nuanced concepts for the topic from a First Nations perspective and third, the concepts presented were constructed using western discourses. However, the four themes outlined still hold important implications for Aboriginal youth mentoring and indicate areas where future Aboriginal-led research can provide deeper understandings. This includes how we can identify ourselves as Aboriginal peoples in western journals and ways in which university libraries house specific collections that make relational mapping part of future research.

Findings from all studies placed a strong emphasis on the first theme of embedding cultural activities and Aboriginal community engagement into program delivery. Cultural activities enabled youth to learn about their culture and develop a greater sense of belonging to their Aboriginal culture (Crooks et al., Citation2017; Farruggia et al., Citation2011; Ferguson et al., Citation2021; Hirsch et al., Citation2016; Kope & Arellano, Citation2016; Ware, Citation2013). These findings hold great benefits for Aboriginal youth. However, in contrast to the positionality of culture being a focus of the program, it was unclear how much collaboration occurred with Aboriginal communities during development and delivery of programs. Most of the studies did not employ Aboriginal researchers throughout the research process.

Studies failed to take up the position that only Aboriginal people can mentor Aboriginal youth, as they are skilled in Aboriginal styles of communication. Aboriginal people highly regard the value of equality, meaning all entities of the lifeworld are equal (McMahon, Citation2017). From this, respectful communication styles may be indirect. Humour, storytelling, teasing, silence, modelling, or yarning may be used instead of directly communication styles (McMahon, Citation2017). The strong focus on culture within the studies resulted in program success (Crooks et al., Citation2017; Farruggia et al., Citation2011; Ferguson et al., Citation2021; Hirsch et al., Citation2016; Kope & Arellano, Citation2016; Ware, Citation2013). However, future programs being designed, led and evaluated by Aboriginal people will significantly elevate this success, and enable deeper understandings of culturally informed design and process.

The second theme, intrapersonal development, discussed individual reflections about self, identity, and to understand levels of confidence and growth. This theme explained how mentoring programs developed individual life skills and experience of decision making. It was discussed that elements of Aboriginal youth mentoring programs were connected to, and enabled leadership (Halsall & Forneris, Citation2018; Hirsch et al., Citation2016; Kope & Arellano, Citation2016). To critique this finding is complex. The sentiment or general understandings of this theme may hold important factors for best practice regarding Aboriginal youth mentoring. However, this theme is also an example of assimilation from the western systems of academia, which may limit engagement with and application of, the research findings in Aboriginal communities. There is a need to strongly position the Aboriginal context. Intrapersonal as a term is not enabling research to be a decolonising activity. It is not allowing opportunity for Aboriginal discourses and language, or the multiple, nuanced understandings which may have been included in this discussion if Aboriginal concepts and values relating to self-identity were given positionality (Snowshoe et al., Citation2017).

The third theme, interpersonal development, is defined as relationships between youth, between youth and their mentors and between youth and their communities. Positive relationships enabled youth to build confidence, new social connections, positive identity and explore leadership opportunities (Crooks et al., Citation2017; Ferguson et al., Citation2021; Halsall & Forneris, Citation2018; Hirsch et al., Citation2016; Lopresti et al., Citation2021; Peralta et al., Citation2018; Pizzirani et al., Citation2019). However, the relationship with Country, nature or Ancestors, was not widely discussed as significant relationships mentoring programs should focus on. This work does not incorporate Aboriginal understandings about relationships with Country and Ancestors. It is limited to understanding the complexities of collective identities and kinship.

Flexibility of programs to evolve, employment of Aboriginal staff and longer duration of programs were elements vital for program design as a fourth theme (Arellano et al., Citation2018). It also was explained that gender was an important consideration; for example, male youth were more likely to engage with male mentors (Crooks et al., Citation2017; Ferguson et al., Citation2021; Lopresti et al., Citation2021; Pizzirani et al., Citation2019). Future studies need to understand all aspects of Aboriginal men's and women's business in program design, enabling deeper thinking and Aboriginal-led community conversations regarding inclusivity of values and perspectives of young Aboriginal LGBTQIA + community members (Bennett & Gates, Citation2019). Aboriginal people leading program delivery and collaboration with Aboriginal communities was discussed (Arellano et al., Citation2018; Crooks et al., Citation2017; Ferguson et al., Citation2021; Hirsch et al., Citation2016; Pizzirani et al., Citation2019; Halsall & Forneris, Citation2018; Lopresti et al., Citation2021; Richards et al., Citation2011; Ritchie et al., Citation2014). However, these findings did not suggest that decision making around program design was Aboriginal-led. It is reflected that important elements of Aboriginal-led program design may have been invisible to non-Aboriginal researchers who collected and analysed data for the studies reviewed for this scoping review. This is a significant limitation for establishing an in-depth understanding of best practice for program design, informed by Aboriginal understandings for wellbeing, and Aboriginal processes for transitioning youth to adulthood and leadership. As Aboriginal mentoring programs become more Aboriginal-led, the requirement for Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property (ICIP) (Kearney et al., Citation2018) rights become more pertinent. Aboriginal youth, mentors, Elders, and community members who engage in program design and delivery will need to have their cultural knowledges, languages, and practices protected. This includes their right to veto use of content and be attributed and re-imbursed for their contributions. Programs need to understand that ICIP rights are inclusive of collective and individual identities, and that the ICIP rights of localised programs are not transferrable to other regions, and programs.

Future practice and research need to better understand Aboriginal mentoring, which is led by Aboriginal mentors, Elders, researchers, and practitioners and is inclusive of the voices of Aboriginal young people. It is essential to ensure the Aboriginal context of the Stolen Generations, structural limitations re housing and employment, and systemic racism is forefront.

Limitations

The three non-Indigenous authors on this article will always struggle to see beyond their Eurocentric lens.

Conclusions

Social work as a global discipline has facilitated normative western narratives for youth wellbeing. This scoping review aimed to identify what is needed to create transformational mentoring experiences for Aboriginal young people and challenged the status quo when research is not Aboriginal-led. Four themes: culture, intrapersonal skills, interpersonal skills and program design emerged from the literature. These themes explained mentoring programs. However, they need to be informed by First Nations relational worldviews. Positioning Aboriginal youth mentoring in western worldviews, the results failed to reveal conceptual understandings of healing spaces, Aboriginal communication and processes, Aboriginal youth leadership or relationships with Ancestors or Country. Aboriginal youth mentoring and program design needs to be led by Aboriginal mentors. This will create transformational experiences for youth to reflect and understand their internal narratives about themselves and to grow stronger in their relationships with others and Country.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Questions broken down into four components: Problem; Intervention; Comparison; and Outcome.

References

- Aldara Yenara. (2022). Aldara Yenara, leading the way. Retrieved January 26, 2023, from https://aldarayenara.com.au/

- Arellano, A., Halsall, T., Forneris, T., & Gaudet, C. (2018). Results of a utilization-focused evaluation of a Right To Play program for Indigenous youth. Evaluation and Program Planning, 66, 156–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2017.08.001

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Bennett, B., & Gates, T. (2019). Teaching cultural humility for social workers serving LGBTQI Aboriginal communities in Australia. Social Work Education, 38(5), 604–617. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2019.1588872

- Carriere, J. M. (2015). Lessons learned from the YTSA open custom adoption program. First Peoples Child & Family Review, 10(1), 39–51. https://doi.org/10.7202/1077181ar

- Crooks, C. V., Exner-Cortens, D., Burm, S., Lapointe, A., & Chiodo, D. (2017). Two years of relationship-focused mentoring for First Nations, Métis, and Inuit adolescents: Promoting positive mental health. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 38(1-2), 87–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-016-0457-0

- Davies, M. (2019). Family is culture. Independent review of Aboriginal children and young people in OOHC. Retrieved January 26, 2023, from https://www.familyisculture.nsw.gov.au/.

- Farruggia, S. P., Bullen, P., Solomon, F., Collins, E., & Dunphy, A. (2011). Examining the cultural context of youth mentoring: A systematic review. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 32(5), 237–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-011-0258-4

- Fast, E. (2014). Exploring the role of culture among urban Indigenous youth in Montreal [Doctoral dissertation, McGill University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

- Ferguson, L. J., Girolami, T., Thorstad, R., Rodgers, C. D., & Humbert, M. L. (2021). “That’s what the program is all about … building relationships”: Exploring experiences in an urban offering of the Indigenous youth mentorship program in Canada. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(2), 733. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020733

- Halsall, T., & Forneris, T. (2018). Evaluation of a leadership program for First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Youth: Stories of positive youth development and community engagement. Applied Developmental Science, 22(2), 125–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2016.1231579

- Hirsch, R., Furgal, C., Hackett, C., Sheldon, T., Bell, T., Angnatok, D., Winters, K., & Pamak, C. (2016). Going off, growing strong: A program to enhance individual youth and community resilience in the face of change in Nain. Nunatsiavut. Etudes/Inuit/Studies, 40(1), 63–84. https://doi.org/10.7202/1040145ar

- Kearney, A., Brady, L. M., & Bradley, J. (2018). A place of substance: Stories of Indigenous place meaning in the southwest Gulf of Carpentaria, northern Australia. Journal of Anthropological Research, 74(3), 360–387. https://doi.org/10.1086/698697

- Klinck, J., Cardinal, C., Edwards, K., Gibson, N., Bisanz, J., & Da Costa, J. (2005). Mentoring programs for Aboriginal youth. Pimatisiwin: A Journal of Aboriginal & Indigenous Community Health, 3(2), 109–130.

- Kope, J., & Arellano, A. (2016). Resurgence and critical youth empowerment in Whitefish River First Nation. Leisure/Loisir, 40(4), 395–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/14927713.2016.1269293

- Lopresti, S., Willows, N. D., Storey, K. E., & McHugh, T.-L. F. (2021). Indigenous youth mentorship program: Key implementation characteristics of a school peer mentorship program in Canada. Health Promotion International, 36(4), 913–923. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daaa090

- Martin, K., & Mirraboopa, B. (2003). Ways of knowing, being and doing: A theoretical framework and methods for Indigenous and indigenist research. Journal of Australian Studies, 27(76), 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/14443050309387838

- McMahon, M. (2017). Lotjpa-nhanuk: Indigenous Australian child-rearing discourses [Doctoral dissertation, La Trobe University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

- McMahon, M. (2021). Victorian Aboriginal Research Accord. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1t-8lbMn-V_nfX7q62QNayQdmZR6WjAe-/view

- O’Chin, H. 2020. An Australian First Nations ontology: Determining an Australian First Nations’ epistemology of belongingness, through examples of an art genre and education pedagogy of Aboriginality [Doctoral dissertation, University of the Sunshine Coast). ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

- Peralta, L., Cinelli, R., & Bennie, A. (2018). Mentoring as a tool to engage Aboriginal youth in remote Australian communities: A qualitative investigation of community members, mentees, teachers, and mentors’ perspectives. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 26(1), 30–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/13611267.2018.1445436

- Pizzirani, B., Skouteris, H., O’Donnell, R., Romano, D., Pirotta, S., & Green, R. (2019). Camp expereince for Indigenous youth living in out of home care.

- Richards, K., Rosevear, L., & Gilbert, R. (2011). Promising interventions for reducing Indigenous juvenile offending. Indigenous Justice Clearinghouse.

- Richardson, W. S., Wilson, M. C., Nishikawa, J., & Hayward, R. S. (1995). The well-built clinical question: A key to evidence-based decisions. ACP Journal Club, 123(3), 12–13. https://doi.org/10.7326/ACPJC-1995-123-3-A12

- Rigney, L.-I. (2001). A first perspective of Indigenous Australian participation in science: Framing Indigenous research towards Indigenous Australian intellectual sovereignty Kaurna Higher Education Journal, Issue. Retrieved Janary 26, 2023, from https://ncis.anu.edu.au/_lib/doc/LI_Rigney_First_perspective.pdf

- Ritchie, S., Wabano, M. J., Russell, K., Enosse, L., & Young, N. (2014). Promoting resilience and wellbeing through an outdoor intervention designed for Aboriginal adolescents. Rural and Remote Health, 14(1), 83–101.

- Sawatsky, A. P., Parekh, N., Muula, A. S., Mbata, I., & Bui, T. (2016). Cultural implications of mentoring in sub-Saharan Africa: A qualitative study. Medical Education, 50(6), 657–669. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12999

- Snowshoe, A., Crooks, C. V., Tremblay, P. F., & Hinson, R. E. (2017). Cultural connectedness and its relation to mental wellness for First Nations youth. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 38(1-2), 67–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-016-0454-3

- Steinhauer, E. (2002). Thoughts on an Indigenous research methodology. Canadian Journal of Native Education, 26(2), 69. https://doi.org/10.14288/cjne.v26i2.195922

- Townsend, A., & McMahon, M. (2021). COVID-19 and BLM: Humanitarian contexts necessitating principles from First Nations World views in an intercultural social work curriculum. The British Journal of Social Work, 51(5), 1820–1838. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcab101

- Ware, V. (2013). Mentoring programs for Indigenous youth at-risk. Retrieved January 26, 2023, from Mentoring programs for Indigenous youth (full publication; 17 Sept 2013 edition) (AIHW).

- Wexler, L. (2009). The importance of identity, history, and culture in the wellbeing of Indigenous youth. The Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth, 2(2), 267–276. https://doi.org/10.1353/hcy.0.0055

- Yap, M., & Yu, E. (2016). Operationalising the capability approach: Developing culturally relevant indicators of Indigenous wellbeing – An Australian example. Oxford Development Studies, 44(3), 315–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600818.2016.1178223

- Youth Affairs Council Victoria. (2022). What is ‘youth mentoring?’ Retrieved January 26, 2023, from https://www.yacvic.org.au/resources/youth-mentoring/#TOC-2