ABSTRACT

Education and knowledge sharing has a long and rich history within Australia prior to, and since invasion. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have always been committed to truth telling and ways of knowing, being, and doing. The process of decolonisation through the implementation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledges and pedagogy is an ongoing commitment in higher education settings and is especially relevant in social work education and practices. Social work has historically been complicit in the oppression and genocide of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and, as a result, continues to struggle to define itself within an Australian context. Through our experiences in higher education settings, we have found the process of decolonising education practices in social work to be challenging but necessary. This review aims to explore and reflect upon current literature that addresses western-centric social work pedagogical practice in Australia and aims to incorporate Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander epistemologies using a positional and narrative lens.

IMPLICATIONS

Engaging Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledges and pedagogy decolonises social work education and practice.

Decolonising social work pedagogy positions social work practice to reflect on the intersectionality of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples without othering within contemporary Australia.

Positioning social work education within an Indigenous pedagogical framework provides a basis for future teaching practices and knowledge sharing.

Acknowledgment of Country

The authors of this article wish to acknowledge the traditional owners of the lands on which we both live, work, and learn, the Wadawurrung people of the Kulin Nation, and pay our respects to their Elders past, present, and emerging. In doing so, we wish to acknowledge the rich and continuing cultures, and that sovereignty of these lands and waterways was never ceded. Through reflecting on what it means to be educators on these sacred lands, we note that continuing cultures, knowledge sharing, and pedagogies have long, complex and expansive histories within Australia prior to invasion and colonisation. We extend this acknowledgment to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, their communities, and their survival.

Social work has a White, colonising, and devastating history within an Australian context (Bennett & Gates, Citation2021; Bessarab et al., Citation2016; Walter et al., Citation2011). As social work educators, it is imperative that we not only recognise this past but actively work towards decolonising the profession through education and an ongoing commitment to allyship and partnership with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Through our work as social work educators, we are committed to the ongoing process of decolonising social work education through the privileging of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voices, alongside prefacing western styles of education and curriculum design with Indigenous pedagogies. For as long as there have been people on these lands, there have been knowledge sharing and pedagogies (Russ-Smith, Citation2019). As social work educators, the utilisation of these pedagogies is an integral part of our role in decolonisation. This article explores the literature around social work education as well as providing a reflective analysis of our understanding of pedagogies and its impact on social work education within an Australian context. Through this article, we aim to provide contextual background on social work within Australia, and its impact on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Further to this, we will analyse the use of Indigenous pedagogies in social work classrooms and how through this privileging we aim to provide an improved and nuanced view of social work and social work education. Additionally in this article, we have each provided positionality statements. These statements aim to give background to the authors and provide context to our reflections on the decolonisation of social work education. It should be noted that positionality statements can be used as a step towards decolonising pedagogy. By positioning ourselves, we are actively reflecting on our own relationships with hegemonic and counter-hegemonic discourses.

Explanation of Terms

Throughout this article, the term Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples will be used when referring to First Nations Australians unless a specific Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander country, or both, is being mentioned. As social workers, it is imperative that we reflect on our use of language and how language has been and can be used to further oppress groups of people. Therefore, when discussing historically and currently oppressed groups of people, it is important to utilise the language they are most comfortable with while also aiming to amplify their voices. The terms decolonising and decolonisation will be used in abundance throughout this article. Russ-Smith (Citation2019) defined decolonisation as “the active and conscious resistance to colonial forces that continue to oppress Indigenous sovereignty” (p. 105). It is important to note that both decolonisation and its horrific predecessor, colonisation, are not one-off events. Rather, the process of colonisation is insidious and constant, and as such, the process of decolonisation needs to be ongoing, ever changing, and deeply personal (Briskman, Citation2014). Further, Briese and Menzel (Citation2020) stated that as educators, it is our responsibility to disrupt and change hegemonic discourses through the process of decolonising curriculum, effectively making the curriculum accessible and culturally safe for all students. It should be noted that the process of decolonisation, and particularly decolonisation in higher education, should primarily stem from non-Indigenous peoples to ameliorate burnout in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander staff (Al-Natour & Mears, Citation2016). This is because much of the work needs to come from those who have actively benefited and continue to benefit from colonisation, while continuing to consult Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Muller (Citation2014) stated that “decolonisation presents an invitation for the settler society to understand and acknowledge the process of colonisation and to collaborate in the decolonisation process with Indigenous peoples” (p. 64). Further, to better understand decolonisation, it is important to look at “Indigenisation” and how these terms interact. Bennett and Gates (Citation2021) defined Indigenisation as “the use of appropriate First Nations Theories and practice methods that can transform the entrenched and sometimes enforced westernised values, norms and philosophies” (p. 133). While we can utilise Indigenisation as a means towards decolonisation, these two terms are not one and the same.

Positionality Statements

Joleen

I am a Gunditjmara, Wotjaboluk, Narangga, and Ngarrindjeri woman on my mother’s side and Irish Australian on my father’s side. I am the eldest in my family and the first in my family to complete my Victorian Certificate of Education, a university degree, and a postgraduate qualification. Both my Mum and Dad never completed Year Nine, and they instilled in me the importance of education. Mum later went on to complete a postgraduate qualification and I have never been prouder!

From an early age, I knew I was different. My earliest memory of racism was in Grade One at primary school. My Grade One teacher was teaching the Grade One and Grade Two students about different cultures and asked us all to stand in two groups. Those who had a “normal” nose were to stand in one group, and those who had a “different” nose to stand in another group. I was five going on six, and I did not know racism existed. I did not know that I had a “different” nose. I thought my nose was “normal”, so I, like many of my classmates, stood in the “normal” nose group. There was a Grade Two teacher and another student who stood in the “different” nose group. After we stood in our groups, my Grade One teacher singled me out of the “normal” nose group and placed me in the “different” nose group with the Grade Two teacher and my fellow student. She then proceeded to tell the classes that we were different because of our noses. That we had different cultures. This was in 1989. Coming to terms with now knowing I was “different” and that I am Aboriginal; I did not know what this meant at the time, and I didn’t even know what racism was. I was a kid!

From that point on, I have experienced racism throughout my education. I began my social work degree in 2002 and while I completed my social work placement in 2004, I experienced racism in a field education setting. I felt my experience of this overt racism was not taken seriously as I tried to address it. I was rebuked and my complaint of racism dismissed. This experience along with others was the catalyst to transfer my studies on-campus to gain a non-Indigenous perspective of social work. The curriculum only referred to Aboriginal people in one week in each of the units I studied, and it was difficult to comprehend the lack of cultural considerations in the degree. I undertook the remainder of the Bachelor of Social Work part-time and completed my degree in 2010.

Fast forward 33 years from that day in 1989 and I am now teaching social work where I found myself decolonising the “othering” and colonising nature of the teaching and learning content of the social work curriculum. This has led to the need to write this article.

Jesse

The whole point of a positionality statement is to provide insight into the authors’ background and where their “position” is in life. This allows for the reader to get a better view of any inherent biases that may be unseen by the author, especially when writing reflectively. That being said, from my experience it’s easier said than done. When sitting down to write my positionality statement I struggled with how to formulate it, telling myself “Stick to the facts, the ones that are easy to put on paper” but that ultimately defeats the purpose. Starting with the facts, I am the second eldest of five. I am a queer, amab non-binary, polyamorous individual. I am well educated and have always had a privileged relationship with education. I grew up on Gudabunad country. I am a second generation Australian on my father’s side with my Baba and Djede (grandparents) having immigrated from Jugoslavia (now Hrvatska/Croatia) in the late 1950s, and this is when it gets a tad mirky. As is the case for a lot of people in Australia, the colonial histories of their families can be blurred and muddied, with records being forged, lost, destroyed, and in some cases non-existent. I have spent a good portion of my life figuring out “who I am” and in all honesty I still have no clue. It took well into my twenties for me to come to terms with my gender and sexuality, and now I am on a journey of coming to terms with my cultures, some of which are lost, stolen, or have been withheld. Growing up, my father’s language was deliberately withheld from me and my siblings as a choice made by my father. However, my father’s histories were ones that were taught to me by my Djede. It was easy to connect to my Croatian heritage as this was very present and othered from what it meant to be a “White Australian”. But there was always that level of unknowing from my mother’s family. I was brought up believing that my mother’s family had a purely colonial history from Scotland, but the details were lacking. I knew that going back matrilineally, the women in my family were educators, with my sister and mother being teachers, and my grandmother being a governess (later a seamstress) who grew up on a sheep station on Barkandji country. And here is where I get stuck, actively fighting with the privileges I have been granted growing up “White” in Australia, while also trying to reconcile a part of me that doesn’t feel complete, a part of me that feels connection to the land I am on while not knowing and fully understanding why or how. I do not feel comfortable with labelling myself as either Indigenous or non-Indigenous as the “rumours” and the truths within my family have been deliberately hidden. Even now it’s difficult for me to write what feels like the truth without concrete evidence, due to the fear of alienation from family who are afraid to speak the truth, and a respect for their fears. However, it’s also important that I actively work towards truth telling as a step forward in my journey of self-discovery and decolonisation. Further to this, as a person on stolen land, and as a social work educator it is important for me to honour the truths and the histories of the peoples and lands on which I live, work, and learn.

Aim

This review sought to answer the question: What does the literature say about decolonising social work education using Indigenous ways of knowing, being, and doing?

Method

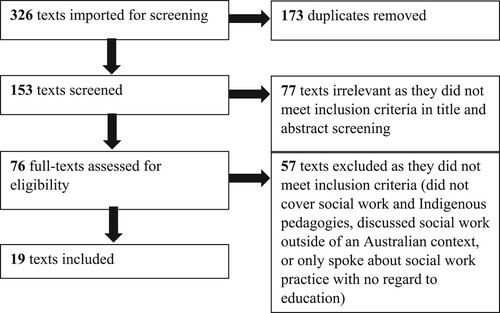

A narrative literature review was undertaken to challenge western-centric ways of research and reflect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledges, and ways of knowing, being, and doing. Both authors undertook the search strategy (outlined in ), which identified texts from 2011–2022, including the databases Informit, Google Scholar, and EBSCOHost, in addition to a snowballing method, and targeted texts referring to social work education in an Australian context. Search terms included decoloni*, higher education pedagogy, social work pedagogy, Indigenous pedagogy, Indigenous ontology, Yarning, storying, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Box 1 Search Strategy

For the purpose of this article, the authors made the decision to focus on literature that was centred on Australian social work education and the experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Texts on the decolonisation of social work in international contexts (such as the United States, Canada, and Aotearoa New Zealand) were excluded. The authors included McNabb (Citation2017) from Aotearoa, as the text referred to social work and First Nations pedagogy in an Australian context. An overview of the number of articles reviewed can be found in . The 19 texts that met the inclusion criteria were written predominantly by authors who identified as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, or both, or allies. The authors reviewed all 19 texts independently and then came together to discuss emergent topics. Both shared the view that five distinctive themes were evident, with 10 of the texts addressing two or more of these themes.

Findings

Themes

The following five themes emerged from our review and discussion of the texts included in this literature review: (1) Allyship and Culturally Responsive Pedagogy; (2) Indigenous Epistemology, Knowledge Sharing and Community Engagement; (3) Whiteness Theory, Racism, and White Fragility; (4) (De)Colonisation; and (5) Indigenising Western-centric Social Work Pedagogy. A little over half of the texts covered two or more of the five themes, with only one text covering all five (see ).

Table 1 Topics by Text

Throughout the literature review, themes around privileging Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander pedagogy, reciprocal knowledge sharing, and the insidious nature of “Whiteness” in Australian social work were explored in depth. Most of the literature was opinion- and text-based with little empirical data through qualitative or quantitative research being explored. Rather, decolonisation of social work practice and education was explored through the voices of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander academics and their allies. It should be noted that there was a large consensus throughout each text that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledges, ways of knowing, being and doing, and pedagogies need to take a central space in Australian social work education to dismantle the invisible hegemonic western-centric views that currently monopolise Australian social work practice and education. Further to this, there was a consensus on the need for reciprocal relationships between the academy and local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities to effectively Indigenise and decolonise social work practice and education. The texts and how each addresses the five key themes are discussed below.

Allyship and Culturally Responsive Pedagogy

Hendrick and Young (Citation2018; Citation2019) used the term “ally work” to describe efforts by non-Indigenous peoples to move towards decolonisation of Australian social work practice and education. Hendrick and Young (Citation2018; Citation2019) stated that non-Indigenous staff need to be critically reflective of their work as allies and regularly critique and challenge the privileges that colonisation has afforded them. Further, non-Indigenous staff must show a commitment to reconciliation, recognition, and restoration as central ideologies of ally work. Bennett and Gates (Citation2021) suggested that advocating for socially responsive pedagogy and university curriculum that is inclusive of all diversities is a key component of ally work. Hendrick and Young (Citation2019) provided a model for ally work, and suggested that allies must accept self-determination, refuse cultural and knowledge appropriation, readily confront their own privileges, and use skills of deep listening and respect when regarding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Moreover, allies should apply and work with Indigenous knowledge systems and pedagogies with permissions. Allies should advocate for change at individual, organisational and policy levels, through the active reconstruction of unequal and discriminatory practices. Further, Hendrick and Young (Citation2019) stated that allies need to be able to help others to “pay the rent”. When thinking about the academy and social work education specifically, it is imperative that non-Indigenous staff ensure that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander staff and students are not being constantly called upon to deliver content that could be particularly retraumatising. Hendrick and Young (Citation2019) suggested that making Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples within the academy relive these past events is voyeuristic in nature and contributes to their experiences of (intergenerational) trauma.

Bennett et al. (Citation2018), Bessarab et al. (Citation2016) and Al-Natour and Mears (Citation2016) all suggested one way that allies can work within an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander space is through moving away from cultural competency towards culturally responsive education and pedagogy. Bennett et al. (Citation2018, p. 812) suggest that culturally responsive pedagogical practice is one where teaching and learning focuses on the integration of students “personal and cultural strengths, their intellectual capabilities and their prior accomplishments”. Culturally responsive pedagogy is therefore transformative and relational in nature. The authors assert the findings from this theme address the polychotomies of power and structures through intersections of race, class, and gender, and further dismantles western-centric hegemonic social work practice and education. It is therefore important for allies to engage Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander staff and communities in developing culturally responsive pedagogies while examining and critically reflecting on their colonial privileges and colonising selves.

Indigenous Epistemology, Knowledge Sharing, and Community Engagement

The Australian Association of Social Workers (AASW) has incorporated Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledges and emphasised the importance of working alongside Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the Australian Social Work Education and Accreditation Standards (ASWEAS) (AASW, Citation2020a), Code of Ethics (AASW, Citation2020b), and Practice Standards (AASW, Citation2013). It is noted that while Bennett and Gates (Citation2021), McNabb (Citation2017) and Russ-Smith (Citation2019) refer to previous versions of the AASW ASWEAS, Code of Ethics, and Practice Standards, there is little to no difference between the versions. McNabb (Citation2017) and Russ-Smith (Citation2019) found that while Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ways of knowing, being, and doing is considered core curriculum within the ASWEAS, Code of Ethics, and Practice Standards to decolonise social work education and practice, the AASW does not provide a framework for universities to operationalise Indigenous ontologies. McNabb (Citation2017) suggested that the AASW need to be more proactive and directive in the process of social work decolonisation frameworks for education and practice. Further, McNabb (Citation2017) stated that while Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social work educators are at the forefront of decolonisation, more work needs to be completed by their non-Indigenous counterparts to ensure success. Added to this are the resource constraints and shortage of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social workers (Bennett & Gates, Citation2021). Staff shortages and resource constraints result in workload issues that place a heavy burden on social work faculty, and constrict their ability and energy to advocate for change within the system. Bennett and Gates (Citation2021) asserted that merely adding Indigenous content to a course through the inclusion of Indigenous placenames and words is superficial and tokenistic. Rather, a total restructure of social work curricula must take place, allowing for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledges to be centred and equal. Irrespective of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander content currently being taught in social work courses, the colonial legacy continues. Social work education that places equal emphasis on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ways of knowing, being, and doing will ultimately enhance social work education for all oppressed groups of peoples (Bennett & Gates, Citation2021).

Bessarab et al. (Citation2016) found that the incorporation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ways of knowing, being, and doing has been at the behest of non-Indigenous peoples, who have ultimately determined how these knowledges should be shared and known within the academy. To gain an equal standing between Aboriginal and western knowledge systems, there needs to be a commitment to the disruption of continual colonial practices. Further, more attention needs to be paid to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander academics, communities, and practitioners. One of the most prominent findings across the literature was the need for relevant community engagement that is reciprocal in nature and provides suitable renumeration for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (Bennett et al., Citation2018; Bessarab et al., Citation2016; Hendrick & Young, Citation2019; Russ-Smith, Citation2019). Bennett and Gates (Citation2021) found that many non-Indigenous academics regularly appropriate Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural knowledge without renumeration and reciprocation. Further, Bennett and Gates (Citation2021) stated that non-Indigenous academics often accept positions of educational power without reflecting on, and while being ignorant towards, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voices and governance. Bennett and Gates (Citation2021) suggested that social work students and educators must be taught about the need for reciprocal, respectful, transparent relationships with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Bennett et al. (Citation2018) also suggested that one way of ensuring reciprocity in these relationships is to guarantee that all generated resources benefit the communities in one way or another. One example of this could include capacity building of local Aboriginal Community-Controlled Organisations (ACCOs).

Whiteness Theory, Racism, and White Fragility

The question of “What does it mean to be White?” is often one that is left unanswered due to the invisible and assumed universality of Whiteness (Walter et al., Citation2011). Conversely, the questions of “What does it mean to be Black?” or “What does it mean to be Aboriginal?” are easier to answer due to the experiences of othering that comes with racial labels in majority White countries such as Australia. Whiteness theory aims to explore the assumed universal nature of Whiteness and aims to make the invisible visible (Walter et al., Citation2011); that is, Whiteness is so engrained and hegemonic that it allows the individual to mask their privileges. Both Walter et al. (Citation2011), and Young and Zubrzycki (Citation2011), suggested that critical Whiteness theory must be used in Australian schools of social work as a step towards the decolonisation of curricula and pedagogy. Social work pedagogy is inherently White. While most schools of social work have significant engagement in and with emancipatory practices and theories (such as feminism, antiracism, antioppressive practice, and critical social work theory), it is important that social work educators recognise that these theories all stem from a place of Whiteness and can ultimately “other” those who are not granted the same privileges (Walter & Baltra-Ulloa, Citation2019; Walter et al., Citation2011). Further, Bessarab et al. (Citation2016) stated that, while well intentioned, the dominant strategies associated with combating racism and oppression are western-centric. That is, antiracist and antioppressive strategies are directly derived from European and American schools of sociology.

Bessarab et al. (Citation2016) stated that Whiteness theorising through a thorough understanding of critical race theory and critical Whiteness theory is needed when working within antiracist pedagogical practices. Further, it is imperative for social work curricula to dismantle Whiteness at a grass roots level. Walter and Baltra-Ulloa (Citation2019) provided descriptions for how to disrupt Whiteness at different levels. Disrupting Whiteness at the structural level involves acknowledging the colonial foundations of Australia, along with recognising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledges and nature’s own knowledges. Further, a commitment to the recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ continual connection to land, sea, and country also is imperative. Disrupting Whiteness at a standpoint level involves the recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander sovereignty. This requires the recognition that all peoples in Australia who have arrived during or since invasion are migrants and inherently benefit from the colonisation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples; thus, threatening the ontological security of Whiteness (Walter & Baltra-Ulloa, Citation2019). Walter and Baltra-Ulloa (Citation2019) went on to state that to disrupt Whiteness at a cultural level, social workers must recognise and dismantle the inherent Whiteness within social work that ultimately supports Australian cultural and racial hierarchy. Therefore, social work educators must be capable of dealing with and sitting within the uncomfortable space of challenging Whiteness. They must be prepared for difficult interpersonal processes, including symptoms of “White fragility”. Similarly, Green and Baldry (Citation2013) explained that non-Indigenous social work students cannot be expected to undergo the process of self-decolonisation if their educators cannot hold discomfort in these spaces. Moreover, Bennett and Gates (Citation2021) asserted that social work educators need to develop cultural self-awareness and the ability to be openly vulnerable in these spaces.

(De)Colonisation

Decolonisation is an ongoing commitment and process (Muller, Citation2014). Embarking on the journey of decolonisation means unsettling the profession of social work regarding the ways it sees itself and its practice (Walter & Baltra-Ulloa, Citation2019). Decolonisation of social work practice and education requires non-Indigenous social workers to sit comfortably with the loss of certain privileges obtained at the oppression of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Hendrick and Young (Citation2018) suggested that rather than decolonisation, social work educators should be looking at decoloniality. It is discussed that coloniality dehumanises, individualises, places focus on self-reliance, is capitalistic in nature, and homogenises and universalises hegemonic groups. Conversely, decoloniality rehumanises, places emphasis on equality and equity, requires coordinated and conscious efforts of all people, and places emphasis on local contexts (Hendrick & Young, Citation2018).

In contrast, McNabb (Citation2017) argued that “decolonisation is the process of a colonised people releasing themselves from collective oppression and asserting their right to self-determination” (p. 124), while Al-Natour and Mears (Citation2016) stated that for decolonisation to occur within social work practice and education, non-Indigenous social workers must first begin by acknowledging colonisation before they can begin conceptualising decolonisation. Further, Al-Natour and Mears (Citation2016) stated that social workers must admit and accept social work’s instrumental involvement with colonisation; that is, through understanding the historical and current contexts of colonisation within Australia, social workers must highlight their involvement in the dispossession and genocide of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Bennett and Gates (Citation2021) argued that prevailing practices of colonisation ensure that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples remain the most significantly disadvantaged population within modern day Australia. This is further exacerbated by the lasting impact of colonised social work education and practice. Bennett and Gates (Citation2021) went on to say that “social work has long tried to save, rescue, or help Indigenous people with methods based on historical charitable roots instead of empowerment” (p. 7). Green and Baldry (Citation2013) explore this concept further, by examining the impact that colonial history of social work has had on the modern context. Green and Baldry (Citation2013) suggested that social workers have earned negative reputations within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, a direct result of the intergenerational traumas that are associated with the social work profession and have created a high level of distrust (Bennett et al., Citation2018). This distrust towards non-Indigenous social workers has created a greater need for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social workers.

Indigenising Western-centric Social Work Pedagogy

Social work education within Australia, while endeavouring to incorporate Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ways of knowing, being, and doing is still largely western-centric (Bessarab et al., Citation2016); namely, while social work schools are currently working on Indigenising content, hegemonic Whiteness is still largely centred within curricula across Australia. Briese and Menzel (Citation2020) discussed their realities and experiences as Aboriginal women within the academy, stating that Whiteness and western centrism is invisible and deeply entrenched throughout all levels of academia. Moreover, Briese and Menzel (Citation2020) noted that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledges are generally othered and not placed as equal to western knowledge systems, generally being “slotted” into specific weeks of the curricula. Furthermore, Zubrzycki et al. (Citation2014) found that, through westernised education systems, social work academics tended to homogenise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander experiences, effectively furthering the effects of ongoing colonisation. Briese and Menzel (Citation2020) went on to state that current education systems are “diametrically opposed to culturally inclusive and safe education” with the burden and onus of Indigenising and decolonising content being placed directly in the hands of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students and staff alike. Further to this, it should be noted that the standard and ongoing practice of benchmarking students against western-centric standards means that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students are continually being colonised rather than being assessed against the standards set by their own ways of knowing, being, and doing.

Briese and Menzel (Citation2020), and Russ-Smith (Citation2019) have suggested that to move towards decolonisation of social work education, social work academics must be accountable to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Further, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledges, ways of knowing, being, and doing, and pedagogy must be incorporated as a central facet of social work curricula. Russ-Smith (Citation2019) highlighted the difficulties of creating a “one-size fits all” model for decolonising curricula due to the heterogeneity between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander countries, nations, and cultures. Rather, Bennett and Gates (Citation2021), Russ-Smith (Citation2019), Bennett et al. (Citation2018), and Bessarab et al. (Citation2016) have argued that schools of social work need to ensure that consultation with local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities occurs during the curriculum development phase. However, Briese and Menzel (Citation2020), Russ-Smith (Citation2019), and Hendrick and Young (Citation2018; Citation2019) also suggested that the use of Indigenous pedagogy can be applied universally across schools of social work within Australia, and that Yarning be placed as a central paradigm within social work education and pedagogy. Bacon (Citation2012) indicated that Yarning as an Indigenous pedagogy is found universally among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures.

Briese and Menzel (Citation2020) provided a Yarning model based on the work of Bessarab and Ng’andu (Citation2010). It is important to note that Yarning is more than a “chat”; rather, it has a series of protocols that educators should follow when utilising this pedagogical practice. These protocols are based on a model of Yarning and refer to Social, Therapeutic, and Collaborative Yarning (Bessarab & Ng’andu, Citation2010). While Bessarab and Ng’andu’s (Citation2010) article referred to these protocols applicable in research, they also can be applied in different settings such as a pedagogical framework. Lin et al. (Citation2016) has applied Yarning in a clinical setting, but the premise remains the same. Social Yarning is the foundation of the Yarning model and establishes connection and relatedness in engaging two or more people in conversation (Bessarab & Ng’andu, Citation2010; Lin et al., Citation2016). Bessarab and Ng’andu (Citation2010) referred to Collaborative Yarning as an active sharing and exploring of information between two or more people. Therapeutic Yarning is closely aligned with storying and narrative theory where the individual shares a yarn about their personal experience that may be traumatic or emotional, or both, with the listener, supporting and affirming the individual’s story (Bessarab & Ng’andu, Citation2010).

Discussion

Gaps and Recommendations

Based on literature included in this review, no-one has yet provided a universal decolonising framework for social work education and practice. The authors acknowledge that while a universal framework could be difficult to implement, given the varying experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, it could set the groundwork for a variety of localised approaches when engaging with Indigenous knowledges and pedagogies. While most of the literature was opinion-based, one article used case studies to implement a culturally responsive pedagogical approach (Bennett et al., Citation2018). Texts identified individual pedagogical frameworks and noted the importance of collaborative work with communities to provide local context. However, much of the literature failed to identify ways to implement and employ these strategies. Additionally, most literature placed minimal focus on decolonisation of social work education covering the topic in one or two paragraphs. It is interesting to note that a little over half of the texts covered two or more of the five themes, with only one text covering all five. provides a useful resource for scholars engaging in dismantling and decolonising social work education and practices and tackling the gaps.

Further work is needed in order to truly provide a culturally safe and responsive space for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students and staff within the social work academy. Throughout the process of this article, our experiences of decolonisation within the social work academy have not only been affirmed but mirrored through Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voices. The decolonisation, Indigenisation, and dismantlement of hegemonic Whiteness is integral to the growth of social work within an Australian context. Adopting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander pedagogies, such as Yarning, as central to social work teaching and learning contributes to these processes. Although decolonisation of social work education and practice is an ongoing challenge, it is reassuring that literature affirms its importance and necessity. This cannot be achieved without allyship, culturally responsive pedagogical frameworks, a reciprocal relationship with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, examining one’s own privileges, Whiteness, racism and fragility, and moving away from a western-centric social work pedagogical approach. Further research is needed to explore the possibility of a decolonising pedagogical framework and how this can be implemented throughout schools of social work, ensuring that room is left for local contextualisation and mutually beneficial collaboration with Australian First Nations peoples.

Conclusion

The above narrative review has discussed themes surrounding the decolonisation of social work education within an Australian context. Through the process of this review, the authors positioned Australian social work education within an Indigenous pedagogical framework paying particular attention to Indigenous ways of knowing, being, and doing, and highlighted how this could provide a strong basis for decolonised social work education. Further research on the development and implementation of an Indigenous pedagogical framework which allows for localised contexts and mutually beneficial collaboration between the social work profession and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples is needed to establish an effective and decolonised education and practice framework.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Al-Natour, R., & Mears, J. (2016). Practice what you preach: Creating partnerships and decolonising the social work curriculum. Advances in Social Work and Welfare Education, 18(2), 52–65.

- Australian Association of Social Workers. (2013). Practice Standards.

- Australian Association of Social Workers. (2020a). Australian Social Work Education and Accreditation Standards.

- Australian Association of Social Workers. (2020b). Code of Ethics.

- Bacon, V. (2012). Yarning and listening yarning and learning through stories. In B. Bennett, S. Green, S. Gilbert, & D. Bessarab (Eds.), Our voices: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social work (1st ed., pp. 136–165). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bennett, B., & Gates, T. G. (2021). Working towards cultural responsiveness and inclusion in Australia: The re-indigenization of social work education. Social Work & Policy Studies: Social Justice, Practice and Theory, 4(2), 133–148. https://openjournals.library.sydney.edu.au/SWPS/article/view/15288

- Bennett, B., Redfern, H., & Zubrzycki, J. (2018). Cultural responsiveness in action: Co-constructing social work curriculum resources with Aboriginal communities. The British Journal of Social Work, 48(3), 808–825. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcx053

- Bessarab, D., Green, S., Zubrzycki, J., Jones, V., Stratton, K., & Young, S. (2016). Getting it right: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge and practices in Australian social work education. In M. A. Hart, A. D. Burton, G. R. D. H. K. Hart, & Y. Pompana (Eds.), International Indigenous voices in social work (pp. 133–148). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Bessarab, D., & Ng’andu, B. (2010). Yarning about yarning as a legitimate method in Indigenous research. International Journal of Critical Indigenous Studies, 3(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcis.v3i1.57

- Briese, J., & Menzel, K. (2020). No more ‘Blacks in the Back’: Adding more than a ‘splash’ of black into social work education and practice by drawing on the works of Aileen Moreton-Robinson and others who contribute to Indigenous standpoint theory. In C. Morley, P. Ablett, C. Nobel, & S. Cowden (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of critical pedagogies for social work (pp. 375–387). Routledge.

- Briskman, L. (2014). Social work with Indigenous communities: A human rights approach (2nd ed.). The Federation Press.

- Green, S., & Baldry, E. (2013). Indigenous social work education in Australia. In B. Bennett, S. Green, S. Gilbert, & D. Bessarab (Eds.), Our voices: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social work (1st ed., pp. 166–180). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hendrick, A., & Young, S. (2018). Teaching about decoloniality: The experience of non-indigenous social work educators. American Journal of Community Psychology, 62(3-4), 306–318. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12285

- Hendrick, A., & Young, S. (2019). Decolonising the curriculum; decolonising ourselves. Working towards restoration through teaching, learning and practice. In J. E. Henriksen, I. Hydle, & B. Kramvig (Eds.), Recognition, reconciliation and restoration: Applying a decolonized understanding in social work and healing processes (pp. 251–270). Orkana Forlag. https://doi.org/10.33673/OOA20201/12

- Lin, I., Green, C., & Bessarab, D. (2016). “Yarn with me”: Applying clinical yarning to improve clinician–patient communication in Aboriginal health care. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 22(5), 377-382. https://doi.org/10.1071/PY16051

- McNabb, D. (2017). Democratising and decolonising social work education: Opportunities for leadership. Advances in Social Work and Welfare Education, 19(1), 121–126. https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.054345135195632

- Muller, L. (2014). A theory for Indigenous Australian health and human service work: Connecting Indigenous knowledge and practice. Allen & Unwin.

- Russ-Smith, J. (2019). Indigenous social work and a Wiradyuri framework to practice. In B. Bennett, & S. Green (Eds.), Our voices: Aboriginal social work (2nd ed., pp. 65–85). Macmillan International.

- Walter, M., & Baltra-Ulloa, A. (2019). Australian social work is White. In B. Bennett, & S. Green (Eds.), Our voices: Aboriginal social work, Second Edition (pp. 65–85). Macmillan International.

- Walter, M., Taylor, S., & Habibis, D. (2011). How White is social work in Australia? Australian Social Work, 64(1), 6–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2010.510892

- Young, S., & Zubrzycki, J. (2011). Educating Australian social workers in the post-apology era: The potential offered by a ‘Whiteness’ lens. Journal of Social Work, 11(2), 159–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017310386849

- Zubrzycki, J., Green, S., Jones, V., Stratton, K., Young, S., & Bessarab, D. (2014). Getting it right: Creating partnerships for change. Integrating Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledges in social work education and practice. Teaching and Learning Framework. Australian Government Office for Learning and Teaching, Sydney.